Play all audios:

Sitting on the bus, she felt stupid. His warning was an overture, the first step in a dance. Why hadn’t she answered in kind? They could have gone to a café. She tried to imagine the

conversation they would have had, talking about the Bodleian Library or the Radcliffe Camera, and all the time, below the surface, talking about something else. SIXTEEN DUNCAN LIKE A LIGHT

flashing at the edge of his vision, he sensed danger. He had wanted to show Mr. Griffin the illustrations in _The Little Mermaid, _pictures he had loved for as long as he could remember.

Now he worried that his teacher wouldn’t appreciate her endless devotion to the handsome prince whose life she saves from shipwreck but who never knows she’s saved him. “Wasn’t there a

film?” Mr. Griffin said vaguely. The frontispiece showed the mermaid and her sisters tending their garden lined with scallop shells. He began to point out the many faults: their faces were

boneless ovals, their hair rippled like a bad Botticelli painting. And the seahorses were a travesty. “They’re actually quite ugly,” he said, “warty, with huge eyes on stalks.” Mr. Griffin’s

own eyes bulged beneath bristling brows as if they were trying to grasp whatever they saw. This was his first job after art school, and the smell of cigarette smoke, other kinds too, clung

to his clothing, mixed with the smell of paint. Sometimes he forgot to remove his bicycle clips. He spoke fiercely about the differences between art, which he worshipped, and craft, an

admirable but lesser undertaking. “Pretty” was one of his worst insults. “Decorative” a close second. Now Duncan studied the picture, trying to view it as a stranger rather than a lifelong

friend. “I’ve never seen a seahorse,” he said, “but I like how there are wispy ink marks and at the same time you can see mermaids and flowers and fish. That’s what I want to do—to make

pictures where a lot is left out but people fill in the details. How do I do that?” “I wish I knew,” Mr. Griffin said, and Duncan understood that he truly did. “All I can suggest is keep

drawing, keep looking at paintings to see how the artist is using the space of the canvas, how the colors and the composition work together. Keep making your own paintings.” He went over to

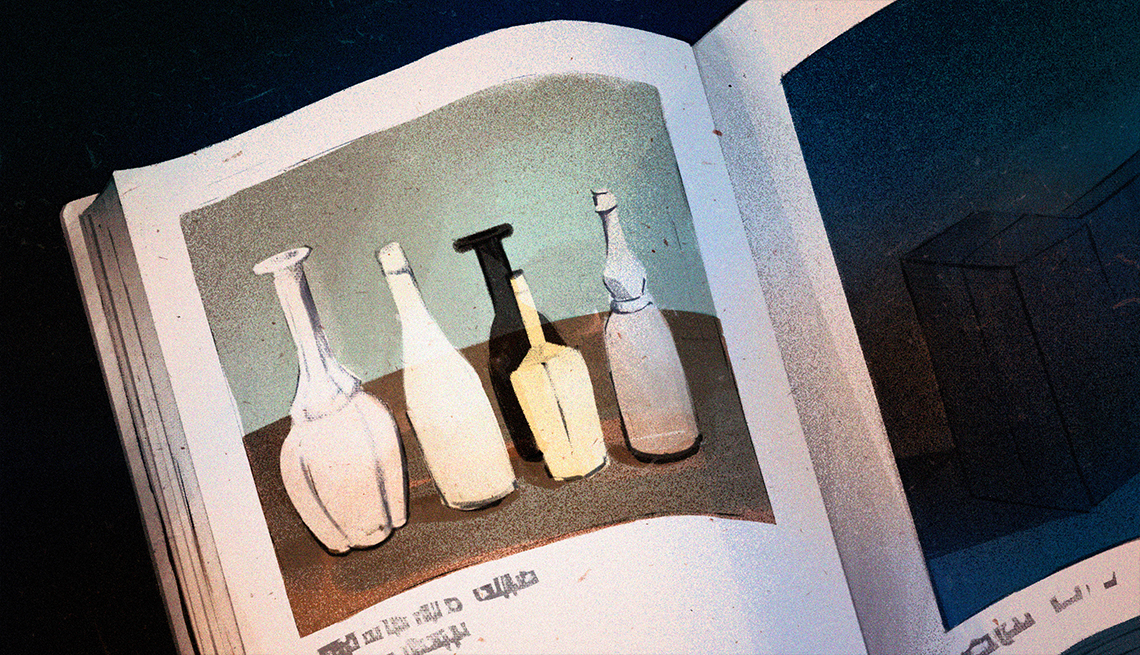

the shelf of art books near his desk and pulled out a slender book with a white cover. “Let me know what you think. He leaves out a lot.” That evening Duncan found himself looking not at

Leda and the Swan, or Europa and the Bull, paintings full of color and movement that told a story, but at five bottles, or flagons, or vases—he wasn’t sure what to call them—each a different

shape. He turned the page and there were the same five bottles, the tallest one on the left. And again, and again. The paintings were small and the colors were cool: grays, purples, ochers,

many shades of white. Sometimes the bottles were so sharply specific, he could have gone into a shop and picked them out of a hundred others. Sometimes they were ghostly, almost irrelevant.

Whoever painted these, thought Duncan, loved the bottles. He imagined them lined up on the table in his beautiful room. His mother had still not mentioned his first mother, but he knew she

had spoken to his father; they both praised him at every opportunity. The next day, during lunch hour, he knocked again on the art room door. When no one answered, he stepped inside,

thinking he would set the book on one of the easels that circled the room, and revisit some of the most intriguing paintings. He was heading for the nearest easel when he spotted Mr. Griffin

seated by an open window, eating a tuna fish sandwich, and smoking. “Hello,” he said quietly. “Bloody hell!” Last year, when he started teaching at the school, Mr. Griffin had used the same

swear words as Duncan’s father, but someone had complained; now he said mostly comic things: “Gordon Bennett!” “Holy mackerel!” “I did knock. You didn’t notice.” “And you didn’t notice that

I’m holding a little white cylinder.” He stubbed out the cigarette. “So what do you think of Mr. Morandi?” Duncan searched for words to describe his journey with the five bottles. At first

the paintings had struck him as simple, even a little dull. Then, as he kept looking, he had begun to understand how they both were, and were not, about the bottles. Sometimes—it was hard to

judge in a reproduction—the brushwork seemed almost clumsy, yet the paintings were complete. “I really, really want to see these paintings,” he said. “Is the painter still alive?”