Play all audios:

To understand what is happening when we forget a person's name, for example, it's useful to look at what happens when we do remember. "Information has to travel long distances

very quickly in our brains," says Sarah Banks, head of neuropsychology at the Cleveland Clinic Lou Ruvo Center for Brain Health in Las Vegas. First, your eyes communicate with your

brain's visual processing center. That information then moves to the region of the brain responsible for recognizing faces. From there, it bounces around in the main memory's

processing center, seeking out associations such as: Do I know her from an old job? Is he the dad of my kid's friend? Then it's off to the brain's language areas, which locate

the random abstract sounds that form a person's name. Finally, Banks says, "that information needs to get to your mouth." These regions — the occipital lobe, the fusiform

gyrus, the hippocampus and the temporal gyrus — are scattered throughout the brain. And all of these connections take place within a millisecond. In short, the wonder is not that we forget

but that we manage to remember anything at all. This goes double for names, since "they are just abstract constructions," says Adam Gazzaley, M.D., professor of neurology,

physiology and psychiatry at the University of California, San Francisco. "It's not like Smith is the smith in your village." A name by itself lacks meaning, which helps

explain why I can fail to come up with the name of a guy at a neighborhood barbecue but could provide enough extraneous information about him to fill an NSA file: He lives in the colonial

down the block, played basketball on his college team and used to work at the same company as my cousin. The same thing happened when Burke asked me the term for a word or phrase spelled the

same backward and forward. My mind darted wildly but found nowhere to land. I knew that the word started with a "p" and that my friend Anna's name was one and so was the

phrase "Madam, I'm Adam." But the word itself, palindrome, eluded me. "Partial information is available," Burke says, "and repeated attempts to retrieve a word

can help." This cognitive slowdown likely results from the fact that the paths these brain signals travel on — our white matter — begin to degrade as we grow older. Think of them as

potholes on our personal information highways and, as such, part of the typical aging process, akin to our vision losing some of its acuity, or our inability to run as fast as we could at

16. It's not — repeat, not — a sure sign of impending dementia any more than needing glasses means we're going blind. Gazzaley also says that distraction, as much as age, is

responsible for many memory glitches. "There's a lot of interference in our modern world," he says, whether it's endless multitasking or constant pings from our high-tech

gadgets. "Our brains' ability to set high-level goals has exceeded our abilities to enact them." No surprise, then, that after going upstairs to fetch a sweater, we often

stare vacantly once we get there. So I'm coming to terms with the fact that this, like achy knees or my inability to sleep soundly, is just another sign of aging. And I'm glad to

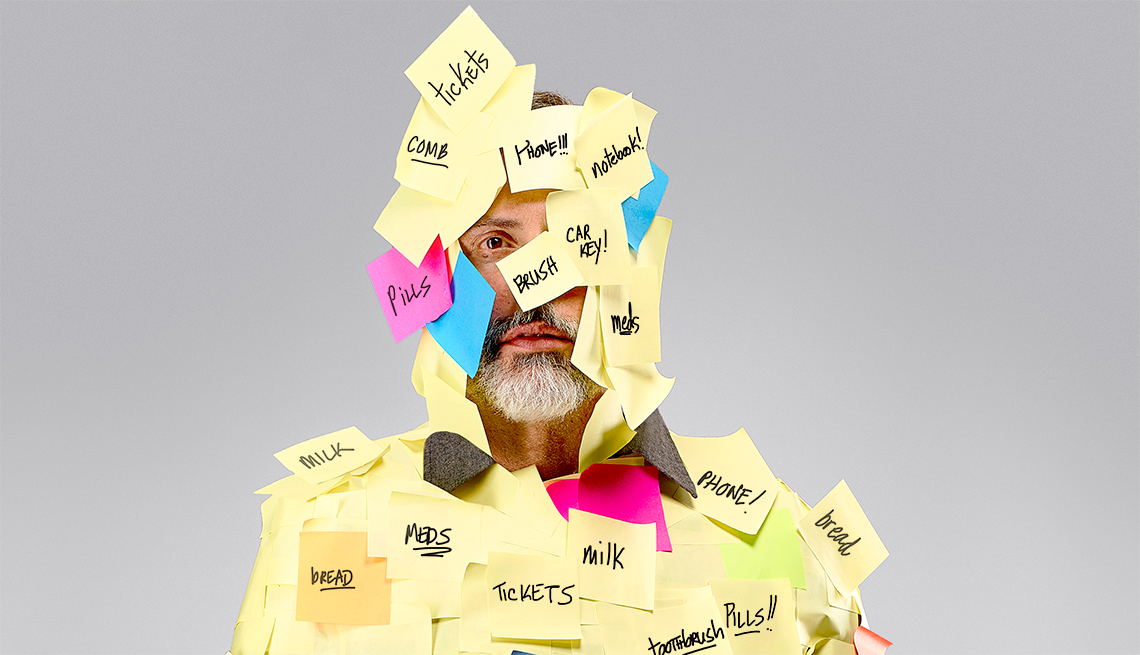

know that these lapses are no cause for concern. "Sure, they're embarrassing at times, but they don't keep anyone from functioning," says Ashton Applewhite, author of

This Chair Rocks: A Manifesto Against Ageism. "Besides, that's why God invented Post-its."