Play all audios:

ABSTRACT BACKGROUND: Long-term effects of psychosocial interventions to reduce emotional distress, sleep difficulties, and fatigue of breast cancer patients are rarely examined. We aim to

assess the effectiveness of three group interventions, based on cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), yoga, and self-hypnosis, in comparison to a control group at a 9-month follow-up.

METHODS: A total of 123 patients chose to participate in one of the interventions. A control group was set up for those who agreed not to participate. Emotional distress, fatigue, and sleep

quality were assessed before (T0) and after interventions (T1), and at 3-month (T2) and 9-month follow-ups (T3). RESULTS: Nine months after interventions, there was a decrease of anxiety

(_P_=0.000), depression (_P_=0.000), and fatigue (_P_=0.002) in the hypnosis group, and a decrease of anxiety (_P_=0.024) in the yoga group. There were no significant improvements for all

the investigated variables in the CBT and control groups. CONCLUSIONS: Our results showed that mind–body interventions seem to be an interesting psychological approach to improve the

well-being of breast cancer patients. Further research is needed to improve the understanding of the mechanisms of action of such interventions and their long-term effects on quality of

life. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS AN EXAMINATION OF THE EFFECTIVENESS OF MINDFULNESS-INTEGRATED COGNITIVE BEHAVIOR THERAPY ON DEPRESSION, ANXIETY, STRESS AND SLEEP QUALITY IN

IRANIAN WOMEN WITH BREAST CANCER: A RANDOMIZED CONTROLLED TRIAL Article Open access 01 April 2025 FOUR-YEAR FOLLOW-UP ON FATIGUE AND SLEEP QUALITY OF A THREE-ARMED PARTLY RANDOMIZED

CONTROLLED STUDY IN BREAST CANCER SURVIVORS WITH CANCER-RELATED FATIGUE Article Open access 15 February 2023 MOBILE HEALTH INTERVENTION CANRELAX REDUCES DISTRESS IN PEOPLE WITH CANCER IN A

RANDOMIZED CONTROLLED TRIAL Article Open access 10 May 2025 MAIN Cancer diagnosis and treatments have significant side effects: pain; physical dysfunction; fatigue; sleep disturbances; and

hair loss (Ewertz and Jensen, 2011; Die Trill, 2013; Weis and Horneber, 2015), as they are associated with the concomitant psychological and emotional reactions such as anxiety, depression,

and distress (Die Trill, 2013; Tojal and Costa, 2015; Hernández Blázquez and Cruzado, 2016). Given the extent of these negative psychosocial consequences, several group interventions have

been evaluated to improve cancer patients’ quality of life (Faller et al, 2013; de Vries and Stiefel, 2014; Mitchell et al, 2014). These programmes, especially those based on cognitive

behavioural therapy (CBT), had benefits on both anxiety and depression after the intervention (Osborn et al, 2006; Groarke et al, 2013; Gudenkauf et al, 2015). Cognitive behavioural therapy

is a ‘time-sensitive, structured, present-oriented psychotherapy directed towards solving current problems and teaching clients skills to modify dysfunctional thinking and behaviour’ (Beck

Institute for Cognitive Behavior Therapy, 2016). A review showed that CBT interventions were related to short- and long-term effects on quality of life in cancer survivors, with only

short-term effects on depression and anxiety (Osborn et al, 2006). Concerning breast cancer patients, Antoni et al (2009) showed that positive effects of CBT intervention for anxiety

appeared to hold for the 12-month observation period, whereas Stagl et al (2015) showed that a cognitive behavioural stress management programme had positive effects on depression and

quality of life up to 15 years. Finally, in their study, Howell et al (2013) identified several trials that effectively used CBT to increase sleep quality and decrease insomnia in cancer

patients. Mind–body interventions such as yoga and hypnosis have also been studied in oncology settings (Mendoza et al, 2016), mostly in breast cancer patients. Yoga includes various fields

such as ethical disciplines, physical postures, and spiritual practices with the aim of uniting mind and body (Smith and Pukall, 2009), whereas hypnosis is defined as ‘a procedure during

which a health professional or researcher suggests that a patient or subject experience changes in sensations, perceptions, thoughts, or behaviour’ (The Executive Committee of the American

Psychological Association – Division of Psychological Hypnosis, 1994). These mind–body approaches began to show short- and mid-term improvements in breast cancer patient fatigue, sleep,

anxiety, and depressive symptoms (Banerjee et al, 2007; Moadel et al, 2007; Farrell-Carnahan et al, 2010; Mustian et al, 2013; Kiecolt-Glaser et al, 2014; Montgomery et al, 2014; Cramer et

al, 2015; Lanctôt et al, 2016). For example, Moadel et al (2007) have shown greater improvements in breast cancer patients at 3 months in the yoga group _vs_ a randomised control group for

quality of life (QoL), emotional well-being, and distressed mood. In addition, Lanctôt et al (2016) demonstrated that compared to a waiting list control group, for which depressive symptoms

increased during 8 weeks of chemotherapy, no similar increase was found in the yoga group. Kiecolt-Glaser et al (2014) have also shown in a randomised controlled 3-month trial for breast

cancer patients that fatigue was reduced and vitality was increased for yoga participants compared to the control group. Groups did not differ on depression at any time. Finally, Mustian et

al (2013) showed the efficacy of a yoga-based intervention to improve sleep quality of cancer survivors. However, Chandwani et al (2014) did not find any differences for mental health or

sleep quality between yoga, stretching, or waiting control groups. Concerning hypnosis, the study of Montgomery et al (2014) randomly assigned breast cancer patients to either CBT plus

hypnosis (CBTH) or an attention control group. They showed that the CBTH group had significantly lower levels of fatigue at the 6-month follow-up, but there was no measure for distress. A

meta-analysis from Cramer et al (2015) also showed that several hypnosis-based interventions positively impacted fatigue and distress. Finally, an online self-hypnosis intervention for

cancer survivors showed promising results in improving sleep (Farrell-Carnahan et al, 2010). These initial results are encouraging, but there is still a lack of long-term data about the

efficacy of yoga (Smith and Pukall, 2009) and hypnosis (Cramer et al, 2015). Our article aims to present the results of a non-randomised study assessing the 9-month follow-up effects of

three interventions (yoga, self-hypnosis, and CBT) in improving emotional distress, sleep quality, and fatigue in breast cancer patients. These three treatment plans will be compared to a

control group, including patients who agreed not to participate in the interventions. For a better understanding of the evolution of the data, we will briefly present the short-term effects

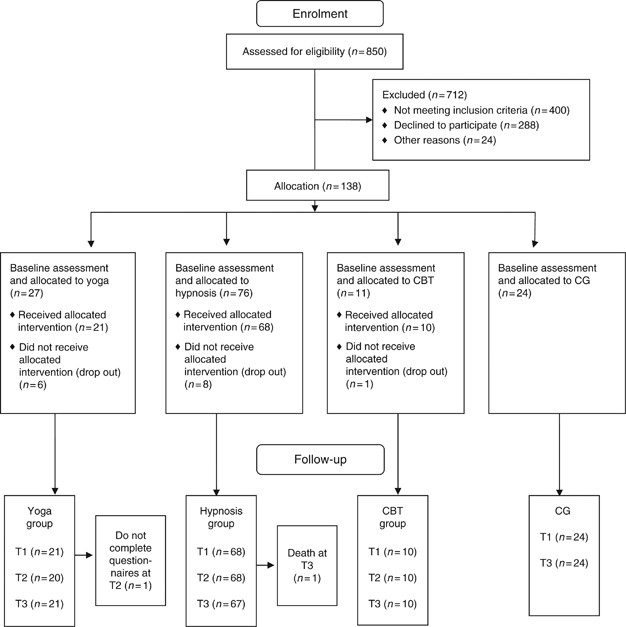

of the interventions (Bragard et al, 2017). We would like to test the hypothesis whether these effects persist over time. MATERIALS AND METHODS PATIENTS AND DESIGN First, 114 patients with

non-metastatic breast cancer were recruited up to 18 months after diagnosis (regardless of cancer stage and type of treatment received). They had to choose to participate in a yoga, a

self-hypnosis, or a CBT group. We chose this kind of design because patients who receive their preferred treatment might be more motivated and could exhibit greater adherence to the

treatment (King et al, 2005; Sedgwick, 2013). Moreover, Mills et al (2015) have already shown that there is not a major difference at baseline between the preference-based groups, as they

are comparable even if they were not randomised. Fifteen of them dropped the study after one or two sessions (6 patients in the yoga group (22.2%); 8 patients in the self-hypnosis group

(10.5%); and 1 patient in the CBT group (9.1%)), leaving a final sample of 99 patients (_N_yoga=21; _N_self-hypnosis=62; _N_CBT=10). Twenty-four patients were also recruited a second time to

form a control group (Figure 1), with the final sample including 123 patients. Inclusion criteria were ⩾18 years old and ability to read, write, and speak French. Patients with a diagnosed

psychiatric disorder or dementia were excluded. After giving written informed consent, participants completed a baseline assessment, including self-reported measures (T0). Three follow-up

assessments were conducted 1 week (T1), 3 months (T2), and 9 months (T3) after the group intervention lasting between 2 and 3 months. For a feasibility issue, the control group completed

questionnaires three times only: at T0; T1; and T3. This paper will focus on the data from the last follow-up (T3), but we will briefly present the results from T1 to give more information

about the evolution of the data. Table 1 shows the principal demographics and medical data of these patients in each group at baseline. INTERVENTIONS Yoga intervention included six weekly 90

min sessions in groups of 3–8 participants, led by trained teachers and developed in Montréal, QC, Canada (Lanctôt et al, 2010). The Bali Yoga Program-Breast Cancer (based on Hatha yoga)

was specifically designed for breast cancer patients. Each participant received a DVD to encourage home practice. More details about the intervention can be found in Bragard et al (2017).

Self-hypnosis/self-care intervention included 6 sessions of 120 min every 2 weeks in groups of 3–8 participants. This was developed and led by one of the authors (MEF), an anaesthetist with

experience in oncology who was also trained in hypnosis (Faymonville et al, 2010). It is a negotiating approach that fosters shared decision-making through tasks on general well-being rather

than the health problem itself. At the end of the session, a 15 min hypnosis exercise was conducted. They received CDs with the hypnosis exercises and homework assignments between sessions

(Vanhaudenhuyse et al, 2015). More details are given in Bragard et al (2017). Cognitive behavioural therapy intervention included 6 weekly 90 min sessions in groups of 3–8 participants led

by CBT-trained psychologists with experience in psycho-oncology. This programme was developed by team leaders (AME, IB, and MD) and modelled on the work of Andersen et al (2009) and Savard

(2010). Relaxation training took place at the end of each session and participants performed tasks between sessions. More details about the intervention are given in Bragard et al (2017).

The control group included patients who agreed not to attend any of the groups. They continued to benefit from their usual care throughout the duration of the study. MEASURES The following

measures were contained in the assessment battery. DEMOGRAPHICS AND MEDICAL HISTORY A questionnaire looking at age, marital status, education, and cancer-related variables (e.g., treatment

types) was completed. THE HOSPITAL ANXIETY DEPRESSION SCALE The Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale (HADS) is a reliable and validated 14-item measure assessing anxiety and depression in

physically ill subjects. Seven items for anxiety and 7 for depression are rated on a 4-point Likert scale (0=symptoms not present to 3=symptoms considerable). Each subscale was scored from 0

to 21 (0–7: ‘normal range;’ 8–10: ‘borderline;’ or 11–21: ‘probable presence of anxiety or depressive disorder’) (Zigmond and Snaith, 1983). EUROPEAN ORGANIZATION FOR RESEARCH AND TREATMENT

OF CANCER-QOL CORE QUESTIONNAIRE-30 The core questionnaire (30 items) to assess the QoL of cancer patients incorporates five functional scales, three symptom scales, a global health

status/QoL scale, and several single items for additional symptoms and the perceived financial impact of the disease. The responses indicate the extent to which the patient experienced

symptoms or problems. Each item is scored on a 4-point Likert scale (‘not at all’ to ‘very much’), excepted for the global health status/QoL that is a 7-point scale (‘very bad’ to

‘excellent’) (Aaronson et al, 1993) In this paper, we only discuss the fatigue-related items of this questionnaire (3 items). INSOMNIA SEVERITY INDEX (Savard et al, 2005) This is a 7-item

measure of subjective sleep complaints and associated distress. Items are scored on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 0 to 4 with higher total scores representing more severe insomnia

symptoms. The cutoff scores are 0–7 (no clinically significant sleep difficulties), 7–14 (sleep difficulties warranting further investigation), and 15+ (presence of clinically significant

insomnia). The data collected from these questionnaires are displayed in Table 2. OUTCOMES The outcome measures assessed the 9-month follow-up effects of three interventions for breast

cancer patients’ emotional distress (anxiety and depression), fatigue, and sleep difficulties, to then compare the three intervention groups with the control group. DATA ANALYSIS Baseline

(T0) demographic, medical, and psychological data were compared between groups to test for initial group equivalency with ANOVA and _χ_2-tests. To be considered for data analysis, patients

attended at least three sessions and completed the first (T0) and last assessments (T3). Group-by-time changes in emotional distress, fatigue, and sleep difficulties were processed using

multivariate analysis of variance with repeated measures, followed by _post hoc_ comparisons (Tukey’s HSD test). All tests were two-tailed and the alpha was set at 0.05. RESULTS Of the 123

women in the intervention or control groups, 1 patient died in the hypnosis group. Thus, in that group, there were data at T0 and T3 for 67 patients; in the yoga group, there were data at T0

and T3 for 21 patients; in the CBT group, there were data at T0 and T3 for 10 patients; and in the control group, there were data at T0 and T3 for 24 patients (Figure 1). The four groups

did not differ at baseline on demographics, medical history, psychological variables (anxiety, depression, fatigue, and sleep quality), or number of sessions (for each group). The average

attendance rate was 5.8 sessions for yoga, 5.4 for self-hypnosis, and 5.7 for CBT. IMPACT OF INTERVENTIONS ON EMOTIONAL DISTRESS, FATIGUE, AND SLEEP QUALITY AT T1 AND T3 To present the

evolution of the data between T0 and T1, we conducted a multivariate analysis of the psychological variables with repeated measures on time of evaluation. No significant effect by group and

no significant group-by-time interaction effect were revealed, but a significant effect of time of the evaluation appeared (∧=0.862; F(4)=4.59; _P_=0.002; =0.14). _Post hoc_ comparisons

revealed a decrease of anxiety (_P_=0.000), depression (_P_=0.004), and fatigue (_P_=0.045) in the hypnosis group, and a decrease of anxiety (_P_=0.010) in the yoga group. Another

multivariate analysis of the psychological variables with repeated measures on time of evaluation (between T0 and T3) indicated no significant effect by group, except for a significant

effect of time of the evaluation (∧=0.795; F(4)=7.23; _P_=0.000; =0.21), and a significant group-by-time interaction effect (∧=0.830; F(12)=1.80; _P_=0.047; =0.07). _Post hoc_ comparisons

revealed a decrease of anxiety (_P_=0.000); depression (_P_=0.000), and fatigue (_P_=0.002) in the hypnosis group, as well as a decrease of anxiety (_P_=0.024) in the yoga group. There were

no significant improvements for all the investigated variables in the CBT and control groups. The graphic evolution of the results over time in each group is displayed in Figure 2. We can

see that in each experimental group, different variables improved over time, as their means decreased, even though some effects are not significant. DISCUSSION This non-randomised study

assessed the 9-month follow-up effects of three interventions (yoga, self-hypnosis, and CBT) in improving emotional distress, fatigue, and sleep quality in breast cancer patients. In all, 99

breast cancer patients participated in the interventions: 68 in the hypnosis group (1 patient died); 21 in the yoga group; and 10 in the CBT group, while 24 participated as a control group.

The number of participants in the hypnosis group has been previously discussed (Bragard et al, 2017) and could be explained in terms of the notoriety of the trainer, and the greater

availability of yoga or individual psychological counselling outside the hospital compared to self-hypnosis. Patients’ demographic, medical, and psychological characteristics were homogenous

in the four groups at baseline. In the self-hypnosis group, there were improvements 9 months after the intervention for anxiety, depression, and fatigue. In the yoga group, anxiety also

decreased at the 9-month follow-up. Given the lack of long-term results regarding the efficacy of mind–body interventions in oncology settings, it is difficult to contrast our results with

existing ones. However, we see that they contrast with those of Chandwani et al (2014), who found no effect of yoga after 6 months on breast cancer patients’ emotional or mental health, but

positive effects of yoga on fatigue at a 6-month follow-up, as did several other authors at a 3-month follow-up (Bower et al, 2011, 2012; Derry et al, 2014; Kiecolt-Glaser et al, 2014). Our

results are congruent with those of Banerjee et al (2007) who found a positive impact of yoga on anxiety in breast cancer patients undergoing radiotherapy. Concerning hypnosis, our results

contrast with those of Jensen et al (2012) who found no effect of an hypnosis-based intervention on anxiety at a 6-month follow-up, but are congruent with the study of Montgomery et al

(2014), where CBTH created lower levels of fatigue at a 6-month follow-up. Despite the fact that we did not investigate the effects of our intervention later than at 9-month follow-up, our

study seems to give a first argument in favour of a long-term effect of alternative psychotherapeutic approaches, especially hypnosis, as part of self-care intervention for emotional

distress and fatigue in breast cancer patients. We found no improvement in the CBT group after 9 months. These results contrast with the review of Osborn et al (2006), showing that CBT

interventions were related to short-term effects on depression and anxiety in cancer survivors, but they are congruent with those of Groarke et al (2013) and Boesen et al (2011), who did not

find long-term effect on distress in their studies. Considering our results, we concluded that the two mind–body interventions led to better outcomes than the control and CBT did,

especially self-hypnosis in terms of improvement of emotional distress and fatigue. The two mind–body interventions were also the only ones to lead to positive results immediately after the

group. More specifically, 1 week after the intervention, emotional distress and fatigue improved in the hypnosis group, whereas anxiety improved in the yoga group. These results suggest that

self-hypnosis is a powerful tool to improve well-being quickly. To explain these differences between the interventions, we can focus on the mechanisms of change of these different

techniques. On one hand, mind–body techniques in general focus on balancing the autonomic nervous system by activating its parasympathetic branch, to reduce the physiological response to

stress. Indeed, mind and body seem to constantly communicate in a bidirectional way (Sawni and Breuner, 2017). Yoga is known to reduce expressive suppression (Dick et al, 2014) and to

develop calmness (Sherman et al, 2013) and mindfulness, which increases attention regulation, body awareness, and emotion regulation. These mechanisms can help to decrease patients’ anxiety.

Hypnosis has three major components, which can influence cognition and emotional regulation: absorption, which is the involvement in a perceptual, imaginative, or ideational experience;

dissociation, which is the mental separation of different components of experience that would usually be processed as a whole; and suggestibility, which is the responsiveness to social

clues, enhancing the propensity to comply with hypnotic instructions and suspending critical judgment (Vanhaudenhuyse et al, 2014). Those hypnotic suggestions also facilitate mind–body

connection and lead to physical, emotional, and behavioural changes (Sawni and Breuner, 2017), which could explain the impact of that intervention on patients’ emotional distress and

fatigue. On the other hand, CBT does not directly address the body, as it focuses on emotion, cognition, and behaviour. This fundamental difference between the techniques used could explain

the differences in our results, especially given the fact that our participants were oncologic patients, all suffering from physical difficulties linked to their cancer. The fact that the

body is very impacted by the disease could explain why mind–body approaches are so pertinent and beneficial for such patients. There are some limitations of this study. First, the small

number of participants in the yoga, CBT, and control groups requires caution in interpreting the findings, as well as the fact that the number of participants in the self-hypnosis group was

significantly higher than in the other groups. Second, our study was not randomised but included a control group to compare to the intervention groups. However, it is likely that patient

interest, driving the intensity of practice and its enjoyment, has a positive role (Carlson and Bultz, 2008). Carlson et al (2014) showed in a randomised study that patient preference was a

strong predictor of outcomes. In their study comparing two active psychosocial interventions in a control group, breast cancer patients who were assigned to their preferred intervention

reported significantly greater improvement in QoL compared to women who received their non-preferred intervention. Another limitation is that the control group did not benefit from the

intervention at all in our study. Indeed, even if they agreed not to participate, the interventions proposed could have been positive for them and it seems important to figure out how to

motivate such patients to engage in the process. In addition, participants in the control group did not complete all the questionnaires for feasibility reasons, which limits some analyses.

Finally, we were only able to assess the effects of the intervention at a 9-month follow-up, despite the fact that more and more studies collect data over longer periods of time. Future

research might investigate the associations between the variables discussed by adopting an experimental design, such as a randomised-controlled trial, which is the most scientifically

rigorous trial design for assessing the efficacy of an intervention (Pocock, 1983; Millat et al, 2005), and by collecting data during longer periods of time. Larger sample sizes would also

help measure more significant effects. Future research might include all types of cancer, not only breast cancer, and some objective measures of emotion regulation and sleep quality such as

cardiac frequency, activity, or sleep pattern monitoring. At a clinical level, our study highlights a need to consider the psychological impact of cancer and proposes different interventions

to help patients cope with it. Our study strongly argues in favour of alternative psychotherapeutic approaches, especially hypnosis-based interventions, to improve fatigue and emotional

distress. As patients are interested in those kinds of therapeutic interventions, increasing our knowledge about them and their mechanisms; thus, proposing them in an appropriate way in the

oncology care routine could be very useful both for health professionals and patients. In conclusion, this study showed the benefits of self-hypnosis in improving anxiety, depression, and

fatigue of breast cancer patients immediately after the intervention and until the 9-month follow-up. Yoga also seems to be useful in decreasing anxiety quickly after the intervention, with

this effect lasting at least 9 months. Larger samples would be necessary to determine differences between the three types of interventions. CHANGE HISTORY * _ 07 NOVEMBER 2017 This paper was

modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication _ REFERENCES * Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, Bullinger M, Cull A,

Duez NJ, Filiberti A, Flechtner H, Fleishman SB, de Haes JC (1993) The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in

international clinical trials in oncology. _J Natl Cancer Inst_ 85: 365–376. Article CAS Google Scholar * Andersen BL, Golden-Kreutz DM, Emery CF, Thiel DL (2009) Biobehavioral

intervention for cancer stress: conceptualization, components, and intervention strategies. _Cogn Behav Pract_ 16: 253–265. Article Google Scholar * Antoni MH, Lechner S, Diaz A, Vargas S,

Holley H, Phillips K, McGregor B, Carver CS, Blomberg B (2009) Cognitive behavioral stress management effects on psychosocial and physiological adaptation in women undergoing treatment for

breast cancer. _Brain Behav Immun_ 23: 580–591. Article CAS Google Scholar * Banerjee B, Vadiraj HS, Ram A, Rao R, Jayapal M, Gopinath KS, Ramesh BS, Rao N, Kumar A, Raghuram N, Hegde S,

Nagendra HR, Prakash Hande M (2007) Effects of an integrated yoga program in modulating psychological stress and radiation-induced genotoxic stress in breast cancer patients undergoing

radiotherapy. _Integr Cancer Ther_ 6: 242–250. Article Google Scholar * Beck Institute for Cognitive Behavior Therapy (2016) What is cognitive behavior therapy (CBT)? Available at:

https://www.beckinstitute.org/get-informed/what-is-cognitive-therapy/. * Boesen EH, Karlsen R, Christensen J, Paaschburg B, Nielsen D, Bloch IS, Christiansen B, Jacobsen K, Johansen C (2011)

Psychosocial group intervention for patients with primary breast cancer: a randomised trial. _Eur J Cancer_ 47: 1363–1372. Article Google Scholar * Bower JE, Garet D, Sternlieb B (2011)

Yoga for persistent fatigue in breast cancer survivors: results of a pilot study. _Evid Based Complement Alternat Med_ 2011: 1–8. Article Google Scholar * Bower JE, Garet D, Sternlieb B,

Ganz PA, Irwin MR, Olmstead R, Greendale G (2012) Yoga for persistent fatigue in breast cancer survivors: a randomized controlled trial. _Cancer_ 118: 3766–3775. Article Google Scholar *

Bragard I, Etienne A-M, Faymonville M-E, Coucke P, Lifrange E, Schroeder H, Wagener A, Dupuis G, Jerusalem G (2017) A nonrandomized comparison study of self-hypnosis, yoga, and

cognitive-behavioral therapy to reduce emotional distress in breast cancer patients. _Int J Clin Exp Hypn_ 65: 189–209. PubMed Google Scholar * Carlson LE, Bultz BD (2008) Mind–body

interventions in oncology. _Curr Treat Options Oncol_ 9: 127–134. Article Google Scholar * Carlson LE, Tamagawa R, Stephen J, Doll R, Faris P, Dirkse D, Speca M (2014) Tailoring mind-body

therapies to individual needs: patients’ program preference and psychological traits as moderators of the effects of mindfulness-based cancer recovery and supportive-expressive therapy in

distressed breast cancer survivors. _JNCI Monogr_ 2014: 308–314. Article Google Scholar * Chandwani KD, Perkins G, Nagendra HR, Raghuram NV, Spelman A, Nagarathna R, Johnson K, Fortier A,

Arun B, Wei Q, Kirschbaum C, Haddad R, Morris GS, Scheetz J, Chaoul A, Cohen L (2014) Randomized, controlled trial of yoga in women with breast cancer undergoing radiotherapy. _J Clin Oncol

Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol_ 32: 1058–1065. Article Google Scholar * Cramer H, Lauche R, Paul A, Langhorst J, Kummel S, Dobos GJ (2015) Hypnosis in breast cancer care: a systematic review of

randomized controlled trials. _Integr Cancer Ther_ 14: 5–15. Article Google Scholar * de Vries M, Stiefel F (2014) Psycho-oncological interventions and psychotherapy in the oncology

setting. _Psycho-Oncology_ In: U Goerling, (ed). Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, pp 121–135. Chapter Google Scholar * Derry HM, Jaremka LM, Bennett JM, Peng J, Andridge R, Shapiro C,

Malarkey WB, Emery CF, Layman R, Mrozek E, Glaser R, Kiecolt-Glaser JK (2014) Yoga and self-reported cognitive problems in breast cancer survivors: a randomized controlled trial.

_Psychooncology_ 24: 958–966. Article Google Scholar * Dick AM, Niles BL, Street AE, DiMartino DM, Mitchell KS (2014) Examining mechanisms of change in a yoga intervention for women: the

influence of mindfulness, psychological flexibility, and emotion regulation on PTSD symptoms. _J Clin Psychol_ 70: 1170–1182. Article Google Scholar * Die Trill M (2013) Anxiety and sleep

disorders in cancer patients. _EJC Suppl_ 11: 216–224. Article Google Scholar * Ewertz M, Jensen AB (2011) Late effects of breast cancer treatment and potentials for rehabilitation. _Acta

Oncol Stockh Swed_ 50: 187–193. Article Google Scholar * Faller H, Schuler M, Richard M, Heckl U, Weis J, Kuffner R (2013) Effects of psycho-oncologic interventions on emotional distress

and quality of life in adult patients with cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. _J Clin Oncol_ 31: 782–793. Article Google Scholar * Farrell-Carnahan L, Ritterdband LM, Bailey ET,

Thorndike FP, Lord HR, Baum LD (2010) Feasibility and preliminary efficacy of a self-hypnosis intervention available on the web for cancer survivors with insomnia. _Electron J Appl Psychol_

6: 10–23. Google Scholar * Faymonville ME, Bejenke C, Hansen E (2010) Hypnotic techniques. In _Handbook of Communication in Anesthesia and Critical Care_. Allan M Cyna: Oxford, UK, pp

249–261. Google Scholar * Groarke A, Curtis R, Kerin M (2013) Cognitive-behavioural stress management enhances adjustment in women with breast cancer. _Br J Health Psychol_ 18: 623–641.

Article Google Scholar * Gudenkauf LM, Antoni MH, Stagl JM, Lechner SC, Jutagir DR, Bouchard LC, Blomberg BB, Glück S, Derhagopian RP, Giron GL, Avisar E, Torres-Salichs MA, Carver CS

(2015) Brief cognitive-behavioral and relaxation training interventions for breast cancer: a randomized controlled trial. _J Consult Clin Psychol_ 83: 677–688. Article Google Scholar *

Hernández Blázquez M, Cruzado JA (2016) A longitudinal study on anxiety, depressive and adjustment disorder, suicide ideation and symptoms of emotional distress in patients with cancer

undergoing radiotherapy. _J Psychosom Res_ 87: 14–21. Article Google Scholar * Howell D, Oliver TK, Keller-Olaman S, Davidson J, Garland S, Samuels C, Savard J, Harris C, Aubin M, Olson K,

Sussman J, Macfarlane J, Taylor C Sleep Disturbance Expert Panel on behalf of the Cancer Journey Advisory Group of the Canadian Partnership Against Cancer (2013) A Pan-Canadian practice

guideline: prevention, screening, assessment, and treatment of sleep disturbances in adults with cancer. _Support Care Cancer Off J Multinatl Assoc Support Care Cancer_ 21: 2695–2706. Google

Scholar * Jensen MP, Gralow JR, Braden A, Gertz KJ, Fann JR, Syrjala KL (2012) Hypnosis for symptom management in womenwith breast cancer: a pilot study. _Int J Clin Exp Hypn_ 60: 135–159.

Article Google Scholar * Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Bennett JM, Andridge R, Peng J, Shapiro CL, Malarkey WB, Emery CF, Layman R, Mrozek EE, Glaser R (2014) Yoga’s impact on inflammation, mood,

and fatigue in breast cancer survivors: a randomized controlled trial. _J Clin Oncol_ 32: 1040–1049. Article Google Scholar * King M, Nazareth I, Lampe F, Bower P, Chandler M, Morou M,

Sibbald B, Lai R (2005) Impact of participant and physician intervention preferences on randomized trials: a systematic review. _JAMA_ 293: 1089–1099. Article CAS Google Scholar * Lanctôt

D, Dupuis G, Anestin A, Bali M, Dubé P, Martin G (2010) Impact of the yoga bali method on quality of life and depressive symptoms among women diagnosed with breast cancer undergoing

chemotherapy. _Psychooncology_ 19 (Suppl.2): 139. Google Scholar * Lanctôt D, Dupuis G, Marcaurell R, Anestin AS, Bali M (2016) The effects of the Bali Yoga Program (BYP-BC) on reducing

psychological symptoms in breast cancer patients receiving chemotherapy: results of a randomized, partially blinded, controlled trial. _J Complement Integr Med_ 13: 405–412. PubMed Google

Scholar * Mendoza ME, Capafons A, Gralow JR, Syrjala KL, Suárez-Rodríguez JM, Fann JR, Jensen MP (2016) Randomized controlled trial of the Valencia model of waking hypnosis plus CBT for

pain, fatigue, and sleep management in patients with cancer and cancer survivors: Valencia model of waking hypnosis for managing cancer-related symptoms. _Psychooncology_ e-pub ahead of

print 28 July 2016 doi:10.1002/pon.4232. * Millat B, Borie F, Fingerhut A (2005) Patient’s preference and randomization: new paradigm of evidence-based clinical research. _World J Surg_ 29:

596–600. Article Google Scholar * Mills N, Khazragui H, Metcalfe C, Lane A, Davis M, Young G, Neal D, Hamdy F, Donovan J (2015) Do people who choose their treatment in a large randomised

trial with parallel preference groups differ at baseline from those who agree to random treatment allocation? Results from the protect study. _Trials_ 16: P109. Article Google Scholar *

Mitchell SA, Hoffman AJ, Clark JC, DeGennaro RM, Poirier P, Robinson CB, Weisbrod BL (2014) Putting evidence into practice: an update of evidence-based interventions for cancer-related

fatigue during and following treatment. _Clin J Oncol Nurs_ 18: 38–58. Article Google Scholar * Moadel AB, Shah C, Wylie-Rosett J, Harris MS, Patel SR, Hall CB, Sparano JA (2007)

Randomized controlled trial of yoga among a multiethnic sample of breast cancer patients: effects on quality of life. _J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol_ 25: 4387–4395. Article Google

Scholar * Montgomery GH, David D, Kangas M, Green S, Sucala M, Bovbjerg DH, Hallquist MN, Schnur JB (2014) Randomized controlled trial of a cognitive-behavioral therapy plus hypnosis

intervention to control fatigue in patients undergoing radiotherapy for breast cancer. _J Clin Oncol_ 32: 557–563. Article Google Scholar * Mustian KM, Sprod LK, Janelsins M, Peppone LJ,

Palesh OG, Chandwani K, Reddy PS, Melnik MK, Heckler C, Morrow GR (2013) Multicenter, randomized controlled trial of yoga for sleep quality among cancer survivors. _J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc

Clin Oncol_ 31: 3233–3241. Article Google Scholar * Osborn RL, Demoncada AC, Feuerstein M (2006) Psychosocial interventions for depression, anxiety, and quality of life in cancer

survivors: meta-analyses. _Int J Psychiatry Med_ 36: 13–34. Article Google Scholar * Pocock SJ (1983) _Clinical Trials: A Practical Approach_. Wiley-Blackwell: Chichester, West Sussex, UK;

New York, NY, USA. Google Scholar * Savard J (2010) Faire face au cancer avec la pensée réaliste (Montréal) Flammarion Québec: Montréal, Canada. * Savard M-H, Savard, Simard S, Ivers H

(2005) Empirical validation of the Insomnia Severity Index in cancer patients. _Psychooncology_ 14: 429–441. Article Google Scholar * Sawni A, Breuner CC (2017) Clinical hypnosis, an

effective mind-body modality for adolescents with behavioral and physical complaints. _Children (Basel)_ 4, pii E19. * Sedgwick P (2013) What is a patient preference trial? _BMJ_ 347: f5970.

Article Google Scholar * Sherman KJ, Wellman RD, Cook AJ, Cherkin DC, Ceballos RM (2013) Mediators of yoga and stretching for chronic low back pain. _Evid Based Complement Alternat Med_

2013: 130818. Article Google Scholar * Smith KB, Pukall CF (2009) An evidence-based review of yoga as a complementary intervention for patients with cancer. _Psychooncology_ 18: 465–475.

Article Google Scholar * Stagl JM, Bouchard LC, Lechner SC, Blomberg BB, Gudenkauf LM, Jutagir DR, Glück S, Derhagopian RP, Carver CS, Antoni MH (2015) Long-term psychological benefits of

cognitive-behavioral stress management for women with breast cancer: 11-year follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. _Cancer_ 121: 1873–1881. Article Google Scholar * The Executive

Committee of the American Psychological Association - Division of Psychological Hypnosis (1994) Definition and description of hypnosis. _Contemp Hypn_ 11: 142–162. Google Scholar * Tojal C,

Costa R (2015) Depressive symptoms and mental adjustment in women with breast cancer. _Psychooncology_ 24: 1060–1065. Article Google Scholar * Vanhaudenhuyse A, Gillet A, Malaise N,

Salamun I, Barsics C, Grosdent S, Maquet D, Nyssen A-S, Faymonville M-E (2015) Efficacy and cost-effectiveness: a study of different treatment approaches in a tertiary pain centre. _Eur J

Pain_ 19: 1437–1446. Article CAS Google Scholar * Vanhaudenhuyse A, Laureys S, Faymonville M-E (2014) Neurophysiology of hypnosis. _Neurophysiol Clin Neurophysiol_ 44: 343–353. Article

CAS Google Scholar * Weis J, Horneber M (2015) _Cancer-Related Fatigue_. Springer Healthcare Ltd.: Tarporley, England. Google Scholar * Zigmond AS, Snaith RP (1983) The hospital anxiety

and depression scale. _Acta Psychiatr Scand_ 67: 361–370. Article CAS Google Scholar Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This work was supported by the ‘Plan National Cancer’ of Belgium

(Grant number 137). We are grateful to all the patients who participated in the study. We also thank the yoga teachers (R Blauwaert, J Van Brabant, and D Dubois), the yoga trainer from

Montreal (A Anestin), the psychologists (I Willems, B Brouette, C Jourdan, and A Wagener), the data managers (I Jupsin and S Uccello), and the psychology students (S Coudert and M Beaupain).

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its

later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Board ‘Comité d'éthique Hospitalo-Facultaire Universitaire de Liège’

(B707201215157), with each participant providing written consent. AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS IB and CG participated in the conception and design of the study, in the acquisition and interpretation

of data, and in drafting the manuscript. A-ME, M-EF, PC, GD, DL, and GJ participated in the conception and design of the study, in the interpretation of data, and in revising the manuscript

critically for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related

to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. AUTHOR INFORMATION Author notes * Charlotte Grégoire and Isabelle Bragard: These authors

contributed equally to this work. AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Health Psychology Department, University of Liege, Liege, 4000, Belgium Charlotte Grégoire & Anne-Marie Etienne * Public

Health Department, University of Liege, Liege, 4000, Belgium Isabelle Bragard * Medical Oncology Department, CHU, Liege, Liege 4000, Belgium Guy Jerusalem * Radiation Oncology Department,

CHU Liege, University of Liege, Liege, 4000, Belgium Philippe Coucke * Psychology Department, University of Quebec at Montreal, Montreal, H2L 2C4, QC, Canada Gilles Dupuis & Dominique

Lanctôt * Algology-Palliative Care Department, CHU Liege, University of Liege, Liege, 4000, Belgium Marie-Elisabeth Faymonville Authors * Charlotte Grégoire View author publications You can

also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Isabelle Bragard View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Guy Jerusalem View author

publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Anne-Marie Etienne View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Philippe

Coucke View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Gilles Dupuis View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google

Scholar * Dominique Lanctôt View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Marie-Elisabeth Faymonville View author publications You can also search

for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to Charlotte Grégoire. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS The authors declare no conflict of interest.

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION This work is published under the standard license to publish agreement. After 12 months the work will become freely available and the license terms will switch to a

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 4.0 Unported License. RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 4.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ Reprints and permissions

ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Grégoire, C., Bragard, I., Jerusalem, G. _et al._ Group interventions to reduce emotional distress and fatigue in breast cancer patients: a 9-month

follow-up pragmatic trial. _Br J Cancer_ 117, 1442–1449 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2017.326 Download citation * Received: 08 May 2017 * Revised: 22 August 2017 * Accepted: 24 August

2017 * Published: 19 September 2017 * Issue Date: 07 November 2017 * DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2017.326 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to

read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing

initiative KEYWORDS * group interventions * emotional distress * breast cancer * yoga * self-hypnosis