Play all audios:

ABSTRACT There has recently been a resurgence of interest in the gastrointestinal pathology observed in patients infected with HIV. The gastrointestinal tract is a major site of HIV

replication, which results in massive depletion of lamina propria CD4 T cells during acute infection. Highly active antiretroviral therapy leads to incomplete suppression of viral

replication and substantially delayed and only partial restoration of gastrointestinal CD4 T cells. The gastrointestinal pathology associated with HIV infection comprises significant

enteropathy with increased levels of inflammation and decreased levels of mucosal repair and regeneration. Assessment of gut mucosal immune system has provided novel directions for

therapeutic interventions that modify the consequences of acute HIV infection. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS PROLONGED EXPERIMENTAL CD4+ T-CELL DEPLETION DOES NOT CAUSE DISEASE

PROGRESSION IN SIV-INFECTED AFRICAN GREEN MONKEYS Article Open access 22 February 2023 HIV-1 TREATMENT TIMING SHAPES THE HUMAN INTESTINAL MEMORY B-CELL REPERTOIRE TO COMMENSAL BACTERIA

Article Open access 10 October 2023 PROBIOTIC SUPPLEMENTATION REDUCES INFLAMMATORY PROFILES BUT DOES NOT PREVENT ORAL IMMUNE PERTURBATIONS DURING SIV INFECTION Article Open access 15 July

2021 MAIN The mucosal surface of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract forms a unique anatomical and physiological niche, serving as a predominant structural and immunological barrier against the

microorganisms of the outside world. In addition, the tightly apposed enterocytes that form the single cell layer of the mucosal epithelium also absorb water and nutrients during the

digestive process, which is critical to host survival. Hence, loss of the integrity of the mucosal surface results in multiple deleterious sequelae. HIV infection leads to loss of CD4 T

cells, which leaves affected individuals mortally susceptible to opportunistic infections. Many of the opportunistic infections that ultimately plague such individuals involve infectious

agents that are normally checked by the mucosal barriers. However, while many AIDS-defining illnesses could be attributed to loss of mucosal immunity and only become manifest years after

acquisition of HIV, many pathological changes, both structural and immunological, occur at the mucosal surfaces from the very onset of HIV infection. In this review we discuss recent studies

that have led to a reappraisal of the pathogenesis of HIV disease and how they relate to early studies that documented the structural and functional abnormalities of the HIV-infected GI

tract. HIV ENTEROPATHY In 1983, HIV was defined as the infectious agent that causes AIDS.1, 2 In 1984, Kotler and colleagues, observing that HIV-infected individuals had histologic

abnormalities of the GI mucosa, malabsorption, and lymphocyte depletion, concluded: “The histologic findings suggest that a specific pathologic process occurs in the lamina propria of the

small intestine and colon in some patients with the syndrome.”3 This finding was almost prescient in its anticipation of the discoveries to come. Indeed, the term “HIV enteropathy” has been

appreciated for as long as it has been known that HIV causes AIDS. The enteropathy that afflicts HIV-infected individuals can occur from the acute phase of the infection through advanced

disease. It involves diarrhea, increased GI inflammation, increased intestinal permeability (up to fivefold higher than in healthy controls) and malabsorption of bile acid and vitamin B12.4,

5, 6 Histologically, the enteropathy involves inflammatory infiltrates of lymphocytes and damage to the GI epithelial layer, including villous atrophy, crypt hyperlasia, and villous

blunting.7, 8, 9 Importantly, these pathologic changes occur in the absence of the detectable bacterial, viral, or fungal enteropathogens that are often associated with enteropathy.7 Hence

there are substantial data demonstrating structural abnormalities within the GI tract of HIV-infected individuals. Although the mechanisms underlying these abnormalities remain poorly

understood, several explanations have been put forward. Some have invoked direct “virotoxic” effects of HIV itself on enterocytes.10, 11, 12, 13 For example, the HIV accessory protein Tat

has been shown to have an inhibitory effect on the uptake of glucose by enterocytes.13 Moreover, HIV gp120 can lead to increased concentrations of calcium in enterocytes, which are

associated with tubulin depolymerization and a decrease in the epithelial cells’ ability to maintain ionic balances.14 This interaction was later shown to involve the orphan G

protein–coupled receptor GPR15/Bob.15 Furthermore, HIV can be found in proximity to abnormally enlarged enterocytes, and it has been postulated that HIV may result in abnormal

differentiation of enterocytes.10 In addition, HIV has been shown to induce increased proliferation of enterocytes in cell culture tissue explants.16 Consistent with the notion that HIV is

directly associated with the observed enteropathy, antiretroviral therapy ameliorates GI symptoms.17 However, the mechanisms by which the virus directly results in the death or dysfunction

of enterocytes remain unclear, and only a few of these studies even suggest that enterocytes actually become infected by the virus.18 Another possible culprit contributing to HIV enteropathy

is local activation of the GI immune system. Infiltration of cytotoxic CD8 T cells, for example, has been observed to result in villous atrophy in individuals with celiac disease.19, 20

Mitogenic T-cell stimulation is sufficient to cause enterocyte abnormalities in _ex vivo_ tissue explants.21 Moreover, proinflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF),

interferon (IFN)-γ, interleukin (IL)-12, and IL-8 have been implicated in the pathology of inflammatory bowel disease.22 In particular, high levels of TNF are thought to cause apoptosis of

enterocytes, and treatment with anti-TNF antibodies is of great clinical benefit to individuals with Crohn's disease.23 With respect to HIV enteropathy, local immune activation likely

plays a formative role; indeed, high levels of proinflammatory mediators such as the beta chemokines24 IL-6, IL-10, and IFN-γ25 are found in the lamina propria of the colon of HIV-infected

individuals. Moreover, the degree of inflammation within the GI tract correlates with viral replication.25, 26, 27 Although systemic immune activation is a hallmark of HIV-infection, its

etiology has remained elusive. However, it has been reasonably postulated that local bacterial invasion across the damaged tight epithelial barrier may allow microbial products to stimulate

the immune system locally, presumably through receptors such as Toll-like receptors.28 Because HIV prefers to infect activated CD4 T cells, a crucial consequence of induction of local

inflammation by any means that also involves CD4 T-cell activation may serve to provide additional targets for the virus, thus augmenting its replication. GASTROINTESTINAL CD4 T-CELL

DEPLETION After the original observations of enteropathy and histological abnormalities in the HIV-infected GI tract, immunologists rapidly turned their attention to the mucosal immune

system, which contains the majority of the body's T cells.29 Early studies using immunohistochemistry showed a proinflammatory infiltration of lymphocytes yet also a striking absence of

CD4 T cells,26, 30 leading to the suggestion that the intestinal mucosa could be a site of significant HIV replication and CD4 T-cell destruction.26 Later studies, also using

immunohistochemistry, confirmed that that the GI tract was indeed significantly depleted of CD4 T cells.27, 31, 32 Moreover, these observations were made in both the large and small

intestine, indicating that the depletion of GI CD4 T cells involves the entire bowel. However, these studies were somewhat restricted in that the majority of the HIV-infected individuals

studied were chronically infected with HIV or in the late stage of AIDS. In efforts to better understand the tempo of HIV disease pathogenesis, SIV infection of rhesus macaques has long

provided an invaluable tool. Indeed, within days of infection, a similarly dramatic depletion of GI CD4 T cells was observed in these animals.33 Furthermore, SIV-infected macaques also

manifest enteropathy,34 which is associated with decreased expression of genes such as trefoils that are involved in mucosal repair.35 Hence, in pathogenic SIV infection of rhesus macaques,

the majority of the body's CD4 T cells are depleted within the short acute phase of the infection—a finding not reflected by analysis of peripheral blood or lymph nodes. In later

studies, the use of flow cytometric analysis allowed for a more rigorous and quantitative examination and phenotypic assessment of GI CD4 T cells in HIV/SIV-infected individuals.36, 37, 38,

39, 40, 41, 42 , 43 Several of these studies examined CD4/CD8 ratios in the duodenum and peripheral blood in order to compare CD4 T-cell depletion between these two anatomical sites; the

results also suggested that the GI tract was preferentially depleted of CD4 T cells. However, in another study, CD4/CD8 ratios in rectal biopsies of HIV-infected individuals were shown to be

similar to those in peripheral blood.40 Moreover, even in HIV-uninfected individuals, CD4/CD8 ratios are lower in the terminal ileum than in peripheral blood,42 indicating that the CD4/CD8

ratio may not be an accurate indicator of CD4 T-cell depletion in tissues. Subsequent studies have concentrated on examining depletion of the specific target of HIV: CD4 T cells that express

the HIV coreceptor CCR5.44 Phenotypic analysis of CD4 T cells in the GI mucosa of healthy individuals has demonstrated that the majority of T cells in mucosal tissues express CCR5 and are

very permissive to _in vitro_ infections.45, 46 Indeed, such analyses have clearly demonstrated almost complete depletion of CCR5+CD4 T cells from mucosal sites of HIV-infected humans and

SIV-infected rhesus macques.40, 41, 42, 43 That CCR5+CD4 T cells are preferentially targeted is consistent with reports showing more extensive depletion from the lamina propria as compared

with inductive sites such as Peyer's patches.41, 47 It is important to note that this occurs rapidly during the acute phase of infection. The preferential loss of CCR5+CD4 T cells from

the GI tract clearly suggests a “virus-centric” mechanism. Indeed, by _in situ_ hybridization, HIV and SIV RNA are readily detectable in biopsies of the GI tract from HIV/SIV-infected

subjects.17, 41, 47, 48, 49 While the detection of viral RNA by _in situ_ hybridization is a reliable marker of ongoing viral replication, such analysis underrepresents the total number of

actual infectious events, since the majority of infected cells do not contain replication-competent provirus.50 Hence, flow cytometric sorting of precisely defined T-cell subsets followed by

quantitative polymerase chain reaction for viral DNA results in the quantification of the number of viral genomes within cell populations of interest.51, 52 This approach has shown that CD4

T cells in the GI tract are 10-fold more frequently infected by the virus than are those in the peripheral blood.53, 54 Importantly, the finding that 60% of GI CD4 T cells are infected by

the virus _in vivo_ suggests that the size of the viral reservoir is orders of magnitude greater than previous studies have suggested.50 Moreover, the CD4 T-cell depletion that occurs during

the acute phase of infection can likely be attributed solely to the effects of direct viral infection. Prevention of the GI CD4 T cell destruction that occurs is, therefore, dependent upon

cessation of GI viral replication. Consistent with this idea is the finding that in individuals in whom viral replication in peripheral blood is controlled for long periods of time without

antiretroviral therapy, called long-term nonprogressors, viral replication in the GI tract appears to be limited while GI-tract CD4 T cells are maintained.55 Although enterocyte dysfunction

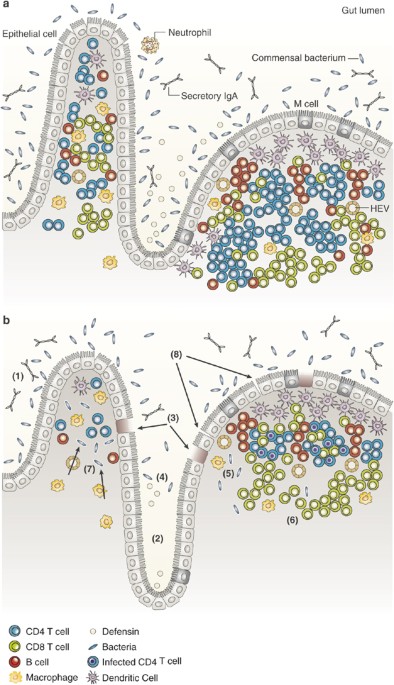

and CD4 T-cell depletion have all been demonstrated within the GI tract of HIV-infected individuals, it is important to note that many other factors contribute to mucosal integrity (Figure

1). The GI tract contains goblet cells that provide a protective mucous layer. Moreover, M cells transport antigens from the lumen of the intestine to Peyer's patches, thus allowing the

adaptive arm of the immune system to “sample” enteric antigens. Specialized intestinal macrophages have also recently been characterized and have been demonstrated to preferentially

phagocytose bacteria without themselves becoming activated.56 Intraepithelial lymphocytes largely comprise γδT cells that recognize antigens presented by nonclassic MHC molecules.57 Finally,

specialized GI Paneth cells are functionally similar to blood granulocytes and produce antimicrobial peptides such beta defensins.58 Moreover, these antimicrobial peptides have been shown

to be inhibitory to HIV replication _in vitro_.59 Hence the mucosal surface is a complex microenvironment of quite distinct but cooperative cells; if or how these cells are affected during

HIV infection is still poorly understood, but it presents an important focus of investigation. Although there is much to learn regarding the pathogenic effects of HIV on the GI tract, it is

clear that the success of any prophylactic HIV vaccine would necessarily depend on its ability to elicit effective HIV-specific immunity at mucosal sites. GASTROINTESTINAL HIV-SPECIFIC

IMMUNE RESPONSES The vast majority of HIV-infected individuals do not control viral replication without therapeutic antiretroviral intervention. However, several studies have suggested a

role for HIV-specific CD8 T cells in controlling viral replication to a set point that persists in chronic infection.60, 61, 62 The lack of such immunity during the first few days of the

infection leaves the virus free to infect GI CD4 T cells, propagate, and spread systemically. Although data on mucosal HIV-specific immunity during the acute phase of infection are scant,

recent studies have investigated HIV-specific T-cell immunity in rectal biopsies of chronically HIV-infected individuals.63, 64 Initially, these studies were restricted to the physical

examination of HIV-specific CD8 T cells using peptide–major histocompatibility complex tetramer technology.63 These studies demonstrated that HIV-specific CD8 T cells were detectable in the

GI tract and that the frequency of HIV-specific CD8 T cells in the GI tract was similar to that observed in peripheral blood, approximately 1% of CD8 T cells.40 However, this is an

overestimate, since these studies did not express the frequency of memory CD8 T cells, which are HIV-specific; moreover, almost all the GI-tract CD8 T cells belong to the memory compartment,

yet naive CD8 T cells circulate in peripheral blood.42 Studies in humans examined only the frequency of HIV-specific CD8 T cells in rectal tissue, but studies of SIV-specific CD8 T cells

with peptide–major histocompatibility complex tetramers have demonstrated that SIV-specific CD8 T cells can be detected in the upper and lower small intestine.65 However, these studies did

not examine the functional capacity of HIV/SIV-specific CD8 T cells in the GI tract. Indeed, in the peripheral blood of HIV-infected individuals, some HIV-specific CD8 T cells that control

viral replication and maintain peripheral blood CD4 T cells are found to produce multiple effector cytokines, including IFN-γ, macrophage-inflammatory protein–1β, TNF-α, and IL-2; they

maintain the ability to degranulate (measured by surface mobilization of CD107a).66 These “polyfunctional” HIV-specific CD8 T cells are rarely found in the peripheral blood of individuals

with progressive HIV infection.66 This finding—combined with the findings of rampant viral replication and CD4 T-cell depletion in the GI tract—led to comparative studies of functional

capacity and the magnitude of SIV/HIV-specific T cells in mucosal sites and peripheral blood. Early studies in SIV-infected rhesus macaques demonstrated inability of SIV-specific CD8 T cells

from the GI tract to produce IFN-γ and TNF-α.67 In addition, in a cohort of chronically HIV-infected individuals, the functional capacity of HIV-specific CD8 T cells in rectal biopsies was

studied; these cells were observed to be similarly skewed toward a predominant “monofunctional” profile (mobilization of CD107a without effector cytokine production), similar to the

functional capacity observed in the peripheral blood of chronically infected individuals.64 In contrast, individuals who are able to control viral replication maintain a polyfunctional

T-cell response in peripheral blood.66 Taken together, these findings strongly suggest that a successful HIV vaccine should induce polyfunctional HIV-specific CD8 T cells within the GI

tract. Indeed, several studies of rhesus macaques have demonstrated vaccine-induced functional SIV-specific CD8 T cells within the GI tract.65, 68, 69 Moreover, the frequency of

vaccine-induced SIV-specific CD8 T cells in the GI tract was negatively correlated with the peak viral load in plasma after challenge with the pathogenic SHIV-ku2, while there was no such

correlation with the frequency of SIV-specific CD8 T cells in peripheral blood.69 Although HIV-specific T-cell responses may reduce viral replication _in vivo_, the prevention of initial

infection would likely require a mucosal humoral immune response. Indeed, investigators using using a pathogenic SIV strain found that the application of SIV-specific neutralizing antibodies

to the vaginal surface can prevent the vaginal infection of rhesus macaques.70 Evidence of such protective humoral immunity in HIV comes from observations that individuals who are

repetitively exposed to the virus yet remain uninfected produce HIV-specific IgA antibodies at mucosal sites.71, 72 However, such antibody responses have not been observed in all cohorts of

exposed uninfected individuals.73 In addition, antibodies directed against host CCR5 have been observed in highly exposed uninfected individuals and in infected individuals classified as

long-term nonprogressors; these antibodies have inhibited HIV transport across human epithelial cells _in vitro_.74, 75 It remains clear, however, that the majority of chronically

HIV-infected individuals do not mount vigorous HIV-specific IgA antibody responses either locally in mucosal sites or systemically.76 Thus, these findings suggest that induction of a

functional HIV-specific immune response would help to control viral replication and might even inhibit it. HAART AND THE GASTROINTESTINAL TRACT Currently available prophylactic

antiretroviral regimens generally reduce plasma viral loads to undetectable levels, resulting in subsequent increases in peripheral blood CD4 T cells.77 It might be expected that viral

replication would be diminished throughout the body and that the CD4 T-cell reconstitution observed in blood would be mirrored at all anatomic sites. Early studies of HIV-associated

enteropathy after the initiation of combination antiretroviral therapy suggested that GI symptoms—such as abdominal cramping, bloating, and loose stools—were significantly improved as soon

as a week after initiation of treatment.17 Moreover, a 1- week period of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) resulted in an approximately 10-fold decrease in viral load (based on

_in situ_ viral RNA and p24 detection) in rectal tissue, with a modest increase of 1 CD4 T cell per microscopic high power field, concomitant with an equally modest decrease in the number of

apoptoic cells in rectal tissue.17 These findings suggest that the virus itself has a central role in the GI tract pathology observed and that HAART can ameliorate enteropathy. Subsequently

a number of groups studied the effects of long-term HAART on GI CD4 T-cell reconstitution in the small bowel (generally the duodenum) using immunohistochemistry and/or flow cytometric

analysis; all concurred that CD4 T-cell reconstitution was poor and occurred at a much slower rate than the reconstitution observed in peripheral blood.41, 78, 79, 80 These studies

demonstrated that individuals treated with HAART during the early stages of HIV infection reconstituted CD4 T cells in the GI tract better (often a twofold increase in the frequency of CD4 T

cells within the GI tract) than individuals treated with HAART during chronic HIV infection (these individuals rarely reconstituted any GI tract CD4 T cells).79, 80 Moreover, poor CD4

T-cell reconstitution after long-term HAART was associated with the continued upregulation of genes involved in immune activation and with low levels of mRNA coding for genes involved in

mucosal repair.80 Importantly, although many of the treated individuals reconstituted peripheral blood CD4 T cells, no HIV-infected individual reconstituted GI tract CD4 T cells to levels

observed in persons uninfected with HIV. The mechanisms underlying meager CD4 T cell reconstitution in the GI tract are poorly understood. However, one possible explanation may be that viral

replication continues at low levels. Few analyses of viral replication within the GI tracts of individuals on HAART have been performed.79, 80, 81 Although decreases in multiply spliced

viral RNAs (indicating actively replicating virus) were observed in rectal biopsies,81 GI CD4 T cells producing virus can still be observed even years after the initiation of HAART.79, 80

These findings may be anecdotal and certainly suggest that a more quantitative and longitudinal examination of infection frequencies within GI CD4 T cell, both before and after the

initiation of HAART, is merited. Continued infection of GI CD4 T cells in HIV-infected individuals receiving HAART could be explained by low local concentrations of antiretroviral drugs.

Whereas the GI tract is well vascularized and the drugs should be bioavalable, high levels of so-called multidrug-resistant proteins, or “toxin pumps,” such as P-glycoprotein, are expressed

on the apical surface of columnar epithelial cells of both the small and large intestine.82, 83 It is tempting to speculate that these multidrug-resistant proteins, which have specificity

for protease inhibitors and nucleoside analogs, may reduce the local concentration of antiretroviral drugs to infected cells within the GI tract and thus allow the virus to slowly replicate

and limit reconstitution of CD4 T cells. A second mechanism that may also reduce an individual's ability to reconstitute GI tract CD4 T cells after HAART is ongoing local

inflammation.80 Indeed, local immune activation has been shown to be associated with fibrosis of the lymphoid architecture in peripheral lymph nodes,42, 84, 85 which in turn predicts the

degree of peripheral blood CD4 T-cell reconstitution after the initiation of HAART.86 Importantly, recent findings suggest that fibrotic deposition of collagen also occurs in GI Peyer's

patches even during the acute phase of the infection; the degree of architectural damage within Peyer's patches similarly predicts GI CD4 T-cell depletion after HAART.87 Although HAART

reduces GI immune activation,80 the ability of the remaining but damaged lymphoid niche to support significant CD4 T-cell reconstitution may be permanently damaged. ENTEROPATHY REVISITED

One of the hallmarks of HIV infection that sets this chronic viral infection apart from others is chronic activation of the immune system.88, 89, 90 This is significant because immune

activation provides the virus with activated CD4 T-cell targets, and it predicts disease progression better than either the peripheral blood CD4 T-cell count or the viral load in plasma.91

However, the underlying causes of systemic immune activation in HIV infection are not well understood. In 1999, Kotler suggested that the consequences of damage to the GI tract may translate

to immune activation within the gut: “The proximity to foreign antigens is the most characteristic distinguishing feature of mucous membranes. Since bacterial lipopolysaccharides stimulate

the release of cytokines, such as TNF, which promotes HIV replication and inflammation [ref.9292 in this article], penetration of foreign antigens could affect the microenvironment within

lamina propria. The process may become chronic and promote persistent recruitment of CD4+ lymphocytes from the systemic circulation and promote their activation and death.”28 Moreover,

increased urinary levels of butyrate, a unique product of colonic microbial metabolism, were observed in individuals with AIDS, leading to the suggestion that “a low, but chronic rate of

bacteria and/or bacterial products seeping across a compromised colonic wall causes a chronic low stress response in AIDS patients.”93 Indeed, damage to the GI tract has been observed to

result in the luminal translocation of microbial products such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS), peptidoglycan, bacterial CpG DNA, flagellae, and viral genomes: molecules that can directly

stimulate the innate immune system through Toll-like receptors. This process, termed microbial translocation, has been observed in numerous diseases, including ulcerative colitis and

Crohn's disease,94 graft-versus-host disease,95 and hepatitis96 as well as after abdominal surgeries97 and in pancreatitis.98 Importantly, in many of these situations the microbial

translocation is associated not only with local inflammation of the gut microenvironment but also with systemic immune activation.99 In light of these findings, we recently investigated

whether microbial translocation occurs in HIV infection and, if so, whether it is associated with chronic systemic immune activation.100 The degree of microbial translocation has typically

been assessed by quantitative measurement of LPS in plasma. Indeed, we found significantly increased levels of plasma LPS in chronically HIV-infected individuals compared with uninfected

individuals, which provides evidence for microbial translocation. The increased levels of LPS were associated with increased levels of soluble CD14 and LPS-binding protein and decreased

levels of antibodies directed against LPS core antigen, pointing to the bioactivity of LPS _in vivo_. Moreover, we found an association between LPS levels and both the frequency of memory

CD8 T cells with an activated phenotype and the levels of the proinflammatory cytokine IFN-α. Importantly, neither of these measures of activation can be directly attributed to LPS. These

findings suggest that plasma LPS, in addition to their potent immunostimulatory activity through Toll-like receptor–4, are also indicators of the translocation of additional microbial

products that stimulate the immune system through other receptors. Indeed, we have also found increased levels of bacterial peptidoglycan in the plasma of HIV-infected individuals.101 LPS

levels decreased after the initiation of HAART, but they remained elevated twofold compared with those found in uninfected individuals; moreover, high plasma LPS levels detected in

HAART-treated individuals were associated with poor CD4 T-cell reconstitution in peripheral blood, consistent with the finding that current HAART regimens allow for only partial repair of

the GI damage that results from HIV-infection. Finally, while pathogenic SIV infection of rhesus macaques is also associated with microbial translocation and immune activation, nonpathogenic

SIV infection of sooty mangabeys—which typically lack high levels of immune activation even in the presence of high viral loads and do not progress to AIDS—is not associated with raised

plasma LPS levels. This suggests that even though these animals are infected with SIV, they somehow maintain mucosal integrity and avert the deleterious consequences of microbial

translocation and systemic immune activation. CONCLUDING REMARKS Pathological changes to the GI tract have long been known to be a characteristic feature of HIV infection. Recent studies

have provided mechanistic insights into the underlying causes of HIV enteropathy and CD4 T-cell depletion, but additional studies are certainly warranted to further our understanding of the

long-term consequences of the assault on the GI tract and the effects of HAART. Although the structural and immunological damage to the mucosae occurs very rapidly during the acute phase of

infection, HIV-infected individuals do not succumb to opportunistic infections for years—not until peripheral blood CD4 T cells become depleted below 200 CD4 T cells per microliter of blood

and mucosal CD4 T cells drop below an as a yet undefined threshold.43 Recent data have shown that the devastation to the GI tract leads to microbial translocation, which is associated with

immune activation100 and, by inference, disease progression;91 however, the relative contribution of microbial translocation and other factors to immune activation is not completely

understood. Moreover the effectiveness of modulating Toll-like receptor–mediated immune activation therapeutically is a tempting although as yet unknown avenue to pursue. In summary, the GI

tract is a site of massive CD4 T-cell depletion and viral infection, enterocyte apoptosis, disruption of tight epithelial junctions, and lymphoid tissue fibrosis. Hence HIV infection could

quite reasonably be considered a disease of the GI tract. Our new understandings in this regard have pointed to new therapeutic directions: the aim would be to prevent or reduce the

propagation of HIV at mucosal surfaces35, 102 and to restore the immunological and epithelial integrity of the mucosal barrier.35 REFERENCES * Barré-Sinoussi, F. _et al_. Isolation of a

T-lymphotropic retrovirus from a patient at risk for acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS). _Science_ 220, 868–871 (1983). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Gallo, R.C. _et al_.

Isolation of human T-cell leukemia virus in acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS). _Science_ 220, 865–867 (1983). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Kotler, D.P., Gaetz, H.P.,

Lange, M., Klein, E.B. & Holt, P.R. Enteropathy associated with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. _Ann. Intern. Med._ 101, 421–428 (1984). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar *

Kapembwa, M.S. _et al_. Altered small-intestinal permeability associated with diarrhoea in human-immunodeficiency-virus–infected Caucasian and African subjects. _Clin. Sci. (Lond.)_ 81,

327–334 (1991). Article CAS Google Scholar * Bjarnason, I. _et al_. Intestinal inflammation, ileal structure and function in HIV. _AIDS_ 10, 1385–1391 (1996). Article CAS PubMed Google

Scholar * Sharpstone, D. _et al_. Small intestinal transit, absorption, and permeability in patients with AIDS with and without diarrhoea. _Gut_ 45, 70–76 (1999). Article CAS PubMed

PubMed Central Google Scholar * Batman, P.A. _et al_. Jejunal enteropathy associated with human immunodeficiency virus infection: quantitative histology. _J. Clin. Pathol._ 42, 275–281

(1989). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Heise, C., Miller, C.J., Lackner, A. & Dandekar, S. Primary acute simian immunodeficiency virus infection of intestinal

lymphoid tissue is associated with gastrointestinal dysfunction. _J. Infect. Dis._ 169, 1116–1120 (1994). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Batman, P.A. _et al_. HIV enteropathy: crypt

stem and transit cell hyperproliferation induces villous atrophy in HIV/Microsporidia-infected jejunal mucosa. _AIDS_ 21, 433–439 (2007). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Heise, C. _et

al_. Human immunodeficiency virus infection of enterocytes and mononuclear cells in human jejunal mucosa. _Gastroenterology_ 100, 1521–1527 (1991). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar *

Fleming, S.C., Kapembwa, M.S., MacDonald, T.T. & Griffin, G.E. Direct _in vitro_ infection of human intestine with HIV-1. _AIDS_ 6, 1099–1104 (1992). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

* Asmuth, D.M., Hammer, S.M. & Wanke, C.A. Physiological effects of HIV infection on human intestinal epithelial cells: an _in vitro_ model for HIV enteropathy. _AIDS_ 8, 205–211

(1994). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Canani, R.B. _et al_. Inhibitory effect of HIV-1 Tat protein on the sodium-D-glucose symporter of human intestinal epithelial cells. _AIDS_

20, 5–10 (2006). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Maresca, M. _et al_. The virotoxin model of HIV-1 enteropathy: involvement of GPR15/Bob and galactosylceramide in the cytopathic

effects induced by HIV-1 gp120 in the HT-29-D4 intestinal cell line. _J. Biomed. Sci._ 10, 156–166 (2003). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Clayton, F. _et al_. Gp120-induced

Bob/GPR15 activation: a possible cause of human immunodeficiency virus enteropathy. _Am. J. Pathol._ 159, 1933–1939 (2001). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Batman,

P.A., Fleming, S.C., Sedgwick, P.M., MacDonald, T.T. & Griffin, G.E. HIV infection of human fetal intestinal explant cultures induces epithelial cell proliferation. _AIDS_ 8, 161–167

(1994). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Kotler, D.P. _et al_. Effect of combination antiretroviral therapy upon rectal mucosal HIV RNA burden and mononuclear cell apoptosis. _AIDS_

12, 597–604 (1998). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Clayton, F., Kapetanovic, S. & Kotler, D.P. Enteric microtubule depolymerization in HIV infection: a possible cause of

HIV-associated enteropathy. _AIDS_ 15, 123–124 (2001). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * MacDonald, T.T. & Spencer, J. The role of activated T cells in transformed intestinal

mucosa. _Digestion_ 46 (Suppl 2), 290–296 (1990). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Ciccocioppo, R. _et al_. Increased enterocyte apoptosis and Fas-Fas ligand system in celiac disease. _Am

J. Clin. Pathol._ 115, 494–503 (2001). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Ferreira, R.C. _et al_. Changes in the rate of crypt epithelial cell proliferation and mucosal morphology

induced by a T-cell–mediated response in human small intestine. _Gastroenterology_ 98, 1255–1263 (1990). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Kam, L.Y. & Targan, S.R. Cytokine-based

therapies in inflammatory bowel disease. _Curr. Opin. Gastroenterol._ 15, 302 (1999). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Targan, S.R. _et al_. A short-term study of chimeric monoclonal

antibody cA2 to tumor necrosis factor alpha for Crohn's disease. Crohn's Disease cA2 Study Group. _N. Engl. J. Med._ 337, 1029–1035 (1997). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar *

Olsson, J. _et al_. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection is associated with significant mucosal inflammation characterized by increased expression of CCR5, CXCR4, and

beta-chemokines. _J. Infect. Dis._ 182, 1625–1635 (2000). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * McGowan, I. _et al_. Increased HIV-1 mucosal replication is associated with generalized

mucosal cytokine activation. _J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr._ 37, 1228–1236 (2004). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Clayton, F. _et al_. Rectal mucosal pathology varies with human

immunodeficiency virus antigen content and disease stage. _Gastroenterology_ 103, 919–933 (1992). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Kotler, D.P., Reka, S. & Clayton, F. Intestinal

mucosal inflammation associated with human immunodeficiency virus infection. _Dig. Dis. Sci._ 38, 1119–1127 (1993). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Kotler, D.P. Characterization of

intestinal disease associated with human immunodeficiency virus infection and response to antiretroviral therapy. _J. Infect. Dis._ 179 (Suppl 3), S454–S456 (1999). Article PubMed Google

Scholar * Lefrancois, L. & Puddington, L. Intestinal and pulmonary mucosal T cells: local heroes fight to maintain the status quo. _Annu. Rev. Immunol._ 24, 681–704 (2006). Article CAS

PubMed Google Scholar * Rodgers, V.D., Fassett, R. & Kagnoff, M.F. Abnormalities in intestinal mucosal T cells in homosexual populations including those with the lymphadenopathy

syndrome and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. _Gastroenterology_ 90, 552–558 (1986). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Ullrich, R., Zeitz, M. & Riecken, E.O. Enteric immunologic

abnormalities in human immunodeficiency virus infection. _Semin. Liver. Dis._ 12, 167–174 (1992). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Clayton, F., Snow, G., Reka, S. & Kotler, D.P.

Selective depletion of rectal lamina propria rather than lymphoid aggregate CD4 lymphocytes in HIV infection. _Clin. Exp. Immunol._ 107, 288–292 (1997). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central

Google Scholar * Veazey, R.S. _et al_. Gastrointestinal tract as a major site of CD4+T cell depletion and viral replication in SIV infection. _Science_ 280, 427–431 (1998). Article CAS

PubMed Google Scholar * Kewenig, S. _et al_. Rapid mucosal CD4+T-cell depletion and enteropathy in simian immunodeficiency virus–infected rhesus macaques. _Gastroenterology_ 116, 1115–1123

(1999). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * George, M.D., Reay, E., Sankaran, S. & Dandekar, S. Early antiretroviral therapy for simian immunodeficiency virus infection leads to

mucosal CD4+T-cell restoration and enhanced gene expression regulating mucosal repair and regeneration. _J. Virol._ 79, 2709–2719 (2005). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

* Lim, S.G. _et al_. Loss of mucosal CD4 lymphocytes is an early feature of HIV infection. _Clin. Exp. Immunol._ 92, 448–454 (1993). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar *

Schneider, T. _et al_. Loss of CD4 T lymphocytes in patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 is more pronounced in the duodenal mucosa than in the peripheral blood. Berlin

Diarrhea/Wasting Syndrome Study Group. _Gut_ 37, 524–529 (1995). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Smit-McBride, Z., Mattapallil, J.J., McChesney, M., Ferrick, D.

& Dandekar, S. Gastrointestinal T lymphocytes retain high potential for cytokine responses but have severe CD4+T-cell depletion at all stages of simian immunodeficiency virus infection

compared to peripheral lymphocytes. _J. Virol._ 72, 6646–6656 (1998). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Guadalupe, M. _et al_. Severe CD4+T-cell depletion in gut

lymphoid tissue during primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection and substantial delay in restoration following highly active antiretroviral therapy. _J. Virol._ 77, 11708–11717

(2003). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Shacklett, B.L. _et al_. Trafficking of human immunodeficiency virus type 1–specific CD8+T cells to gut-associated lymphoid

tissue during chronic infection. _J. Virol._ 77, 5621–5631 (2003). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Mehandru, S. _et al_. Primary HIV-1 infection is associated with

preferential depletion of CD4+T lymphocytes from effector sites in the gastrointestinal tract. _J. Exp. Med._ 200, 761–770 (2004). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar *

Brenchley, J.M. _et al_. CD4+T cell depletion during all stages of HIV disease occurs predominantly in the gastrointestinal tract. _J. Exp. Med._ 200, 749–759 (2004). Article CAS PubMed

PubMed Central Google Scholar * Picker, L.J. _et al_. Insufficient production and tissue delivery of CD4+memory T cells in rapidly progressive simian immunodeficiency virus infection. _J.

Exp. Med._ 200, 1299–1314 (2004). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Schuitemaker, H. _et al_. Biological phenotype of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 clones at

different stages of infection: progression of disease is associated with a shift from monocytotropic to T-cell tropic virus populations. _J. Virol._ 66, 1354–1360 (1992). Article CAS

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Poles, M.A., Elliott, J., Taing, P., Anton, P.A. & Chen, I..S. A preponderance of CCR5(+) CXCR4(+) mononuclear cells enhances gastrointestinal

mucosal susceptibility to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. _J. Virol._ 75, 8390–8399 (2001). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Lapenta, C. _et al_. Human

intestinal lamina propria lymphocytes are naturally permissive to HIV-1 infection. _Eur. J. Immunol._ 29, 1202–1208 (1999). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Li, Q. _et al_. Peak SIV

replication in resting memory CD4+T cells depletes gut lamina propria CD4+T cells. _Nature_ 434, 1148–1152 (2005). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Heise, C., Vogel, P., Miller, C.J.,

Halsted, C.H. & Dandekar, S. Simian immunodeficiency virus infection of the gastrointestinal tract of rhesus macaques. Functional, pathological, and morphological changes. _Am. J.

Pathol._ 142, 1759–1771 (1993). CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Smith, P.D., Fox, C.H., Masur, H., Winter, H.S. & Alling, D.W. Quantitative analysis of mononuclear cells

expressing human immunodeficiency virus type 1 RNA in esophageal mucosa. _J. Exp. Med._ 180, 1541–1546 (1994). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Chun, T.W. _et al_. Quantification of

latent tissue reservoirs and total body viral load in HIV-1 infection. _Nature_ 387, 183–188 (1997). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Douek, D.C. _et al_. HIV preferentially infects

HIV-specific CD4+T-cells. _Nature_ 417, 95–98 (2002). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Brenchley, J.M. _et al_. T-cell subsets that harbor human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) _in

vivo_: implications for HIV pathogenesis. _J. Virol._ 78, 1160–1168 (2004). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Mattapallil, J.J. _et al_. Massive infection and loss of

memory CD4+T cells in multiple tissues during acute SIV infection. _Nature_ 434, 1093–1097 (2005). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Mehandru, S. _et al_. Mechanisms of

Gastrointestinal CD4+T-cell depletion during acute and early human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. _J. Virol._ 81, 599–612 (2007). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Sankaran,

S. _et al_. Gut mucosal T cell responses and gene expression correlate with protection against disease in long-term HIV-1–infected nonprogressors. _Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA_ 102, 9860–9865

(2005). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Smith, P.D., Ochsenbauer-Jambor, C. & Smythies, L.E. Intestinal macrophages: unique effector cells of the innate immune

system. _Immunol. Rev._ 206, 149–159 (2005). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Goodman, T. & Lefrancois, L. Intraepithelial lymphocytes. Anatomical site, not T cell receptor form,

dictates phenotype and function. _J. Exp. Med._ 170, 1569–1581 (1989). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Ayabe, T. _et al_. Secretion of microbicidal alpha-defensins by intestinal

Paneth cells in response to bacteria. _Nat. Immunol._ 1, 113–118 (2000). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Nakashima, H., Yamamoto, N., Masuda, M. & Fujii, N. Defensins inhibit HIV

replication _in vitro_. _AIDS_ 7, 1129 (1993). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Koup, R.A. _et al_. Temporal association of cellular immune response with the initial control of

viremia in primary HIV-1 syndrome. _J. Virol._ 68, 4650–4655 (1994). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Price, D.A. _et al_. Positive selection of HIV-1 cytotoxic T

lymphocyte escape variants during primary infection. _Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA_ 94, 1890–1895 (1997). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Jin, X. _et al_. Dramatic rise

in plasma viremia after CD8(+) T cell depletion in simian immunodeficiency virus–infected macaques. _J. Exp. Med._ 189, 991–998 (1999). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

* Shacklett, B.L. _et al_. Optimization of methods to assess human mucosal T-cell responses to HIV infection. _J. Immunol. Methods_ 279, 17–31 (2003). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

* Critchfield, J.W. _et al_. Multifunctional HIVgag specific CD8+T-cell responses in rectal mucosa and PBMC during chronic HIV-1 infection. _J. Virol._ 81, 5460–5471 (2007). Article CAS

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Schmitz, J.E. _et al_. Simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV)-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes in gastrointestinal tissues of chronically SIV-infected

rhesus monkeys. _Blood_ 98, 3757–3761 (2001). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Betts, M.R. _et al_. HIV nonprogressors preferentially maintain highly functional HIV-specific

CD8+T-cells. _Blood_ 107, 4781–4789 (2006). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Hel, Z. _et al_. Impairment of gag-specific CD8(+) T-cell function in mucosal and systemic

compartments of simian immunodeficiency virus mac251- and simian-human immunodeficiency virus KU2-infected macaques. _J. Virol._ 75, 11483–11495 (2001). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central

Google Scholar * Stevceva, L. _et al_. Both mucosal and systemic routes of immunization with the live, attenuated NYVAC/simian immunodeficiency virus SIV(gpe) recombinant vaccine result

in gag-specific CD8(+) T-cell responses in mucosal tissues of macaques. _J. Virol._ 76, 11659–11676 (2002). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Belyakov, I.M. _et al_.

Impact of vaccine-induced mucosal high-avidity CD8+CTLs in delay of AIDS viral dissemination from mucosa. _Blood_ 107, 3258–3264 (2006). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

* Veazey, R.S. _et al_. Prevention of virus transmission to macaque monkeys by a vaginally applied monoclonal antibody to HIV-1 gp120. _Nat. Med._ 9, 343–346 (2003). Article CAS PubMed

Google Scholar * Devito, C. _et al_. Mucosal and plasma IgA from HIV-1-exposed uninfected individuals inhibit HIV-1 transcytosis across human epithelial cells. _J. Immunol._ 165, 5170–5176

(2000). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Broliden, K. _et al_. Functional HIV-1 specific IgA antibodies in HIV-1 exposed, persistently IgG seronegative female sex workers. _Immunol.

Lett._ 79, 29–36 (2001). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Dorrell, L. _et al_. Absence of specific mucosal antibody responses in HIV-exposed uninfected sex workers from the Gambia.

_AIDS_ 14, 1117–1122 (2000). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Barassi, C., Lazzarin, A. & Lopalco, L. CCR5-specific mucosal IgA in saliva and genital fluids of HIV-exposed

seronegative subjects. _Blood_ 104, 2205–2206 (2004). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Bomsel, M. _et al_. Natural mucosal antibodies reactive with first extracellular loop of CCR5

inhibit HIV-1 transport across human epithelial cells. _AIDS_ 21, 13–22 (2007). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Mestecky, J. _et al_. Paucity of antigen-specific IgA responses in

sera and external secretions of HIV-type 1–infected individuals. _AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses_ 20, 972–988 (2004). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Smith, K. _et al_. Long-term

changes in circulating CD4 T lymphocytes in virologically suppressed patients after 6 years of highly active antiretroviral therapy. _AIDS_ 18, 1953–1956 (2004). Article PubMed Google

Scholar * Miao, Y.M. _et al_. Elevated mucosal addressin cell adhesion molecule-1 expression in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome is maintained during antiretroviral therapy by intestinal

pathogens and coincides with increased duodenal CD4 T cell densities. _J. Infect. Dis._ 185, 1043–1050 (2002). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Mehandru, S. _et al_. Lack of mucosal

immune reconstitution during prolonged treatment of acute and early HIV-1 Infection. _PLoS Med._ 3, e484 (2006). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Guadalupe, M. _et al_.

Viral suppression and immune restoration in the gastrointestinal mucosa of human immunodeficiency virus type 1–infected patients initiating therapy during primary or chronic infection. _J.

Virol._ 80, 8236–8247 (2006). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Talal, A.H. _et al_. Virologic and immunologic effect of antiretroviral therapy on HIV-1 in

gut-associated lymphoid tissue. _J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr._ 26, 1–7 (2001). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Srinivas, R.V., Middlemas, D., Flynn, P. & Fridland, A. Human

immunodeficiency virus protease inhibitors serve as substrates for multidrug transporter proteins MDR1 and MRP1 but retain antiviral efficacy in cell lines expressing these transporters.

_Antimicrob. Agents Chemother._ 42, 3157–3162 (1998). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Thiebaut, F. _et al_. Cellular localization of the multidrug-resistance gene

product P-glycoprotein in normal human tissues. _Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA_ 84, 7735–7738 (1987). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Schacker, T.W. _et al_. Lymphatic

tissue fibrosis is associated with reduced numbers of naive CD4+T cells in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. _Clin. Vaccine Immunol._ 13, 556–560 (2006). Article CAS PubMed

PubMed Central Google Scholar * Estes, J.D. _et al_. Simian immunodeficiency virus–induced lymphatic tissue fibrosis is mediated by transforming growth factor beta 1–positive regulatory T

cells and begins in early infection. _J. Infect. Dis._ 195, 551–561 (2007). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Schacker, T.W. _et al_. Amount of lymphatic tissue fibrosis in HIV

infection predicts magnitude of HAART-associated change in peripheral CD4 cell count. _AIDS_ 19, 2169–2171 (2005). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Estes, J.D. _et al_. CD4 Reconstitution

of Lymphoid Tissues Is Dependent on Earlier Initiation of HAART. Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infection, 27 Feb 2007, Los Angeles, CA. * Lane, H.C. _et al_. Abnormalities of

B-cell activation and immunoregulation in patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. _N. Eng. J. Med._ 309, 453–458 (1983). Article CAS Google Scholar * Hellerstein, M. _et

al_. Directly measured kinetics of circulating T lymphocytes in normal and HIV-1–infected humans. _Nat. Med._ 5, 83–89 (1999). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Hazenberg, M.D. _et

al_. T-cell division in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)–1 infection is mainly due to immune activation: a longitudinal analysis in patients before and during highly active antiretroviral

therapy (HAART). _Blood_ 95, 249–255 (2000). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Giorgi, J.V. _et al_. Shorter survival in advanced human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection is more

closely associated with T lymphocyte activation than with plasma virus burden or virus chemokine coreceptor usage. _J. Infect. Dis._ 179, 859–870 (1999). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

* Duh, E.J., Maury, W.J., Folks, T.M., Fauci, A.S. & Rabson, A.B. Tumor necrosis factor alpha activates human immunodeficiency virus type 1 through induction of nuclear factor binding

to the NF-kappa B sites in the long terminal repeat. _Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA_ 86, 5974–5978 (1989). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Stein, T.P. _et al_. Weight

loss, the gut and the inflammatory response in AIDS patients. _Cytokine_ 9, 143–147 (1997). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Caradonna, L. _et al_. Enteric bacteria,

lipopolysaccharides and related cytokines in inflammatory bowel disease: biological and clinical significance. _J. Endotoxin Res._ 6, 205–214 (2000). CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Cooke,

K.R., Olkiewicz, K., Erickson, N. & Ferrara, J.L. The role of endotoxin and the innate immune response in the pathophysiology of acute graft versus host disease. _J. Endotoxin. Res._ 8,

441–448 (2002). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Caradonna, L. _et al_. Biological and clinical significance of endotoxemia in the course of hepatitis C virus infection. _Curr. Pharm.

Des._ 8, 995–1005 (2002). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Buttenschoen, K. _et al_. Endotoxemia and acute-phase proteins in major abdominal surgery. _Am. J. Surg._ 181, 36–43

(2001). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Penalva, J.C. _et al_. A study of intestinal permeability in relation to the inflammatory response and plasma endocab IgM levels in patients

with acute pancreatitis. _J. Clin. Gastroenterol._ 38, 512–517 (2004). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Smale, S., Tibble, J. & Bjarnason, I. Small intestinal permeability. _Curr.

Opin. Gastroenterol._ 16, 134–139 (2000). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Brenchley, J.M. _et al_. Microbial translocation is a cause of systemic immune activation in chronic HIV

infection. _Nat. Med._ 12, 1365–1371 (2006). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Brenchley, J.M. _et al_. Microbial translocation is a cause of systemic immune activation in chronic HIV

infection. Keystone Symposium, 27 March 2007, Whistler, Canada. * Veazey, R.S. _et al_. Protection of macaques from vaginal SHIV challenge by vaginally delivered inhibitors of virus-cell

fusion. _Nature_ 438, 99–102 (2005). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Mowat, A.M. Anatomical basis of tolerance and immunity to intestinal antigens. _Nat. Rev. Immunol._ 3, 331–341

(2003). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar Download references AUTHOR INFORMATION AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Human Immunology Section, Vaccine Research Center, National Institute of

Allergy and infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland, USA J M Brenchley & D C Douek Authors * J M Brenchley View author publications You can also search for

this author inPubMed Google Scholar * D C Douek View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to D C Douek.

POWERPOINT SLIDES POWERPOINT SLIDE FOR FIG. 1 RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Brenchley, J., Douek, D. HIV infection and the

gastrointestinal immune system. _Mucosal Immunol_ 1, 23–30 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1038/mi.2007.1 Download citation * Received: 24 April 2007 * Accepted: 30 May 2007 * Published: 11

December 2007 * Issue Date: January 2008 * DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/mi.2007.1 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content: Get shareable

link Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative