Play all audios:

ABSTRACT The research agenda for global mental health and substance-use disorders has been largely driven by the exigencies of high health burdens and associated unmet needs in low- and

middle-income countries. Implementation research focused on context-driven adaptation and innovation in service delivery has begun to yield promising results that are improving the quality

of, and access to, care in low-resource settings. Importantly, these efforts have also resulted in the development and augmentation of local, in-country research capacities. Given the

complex interplay between mental health and substance-use disorders, medical conditions, and biological and social vulnerabilities, a revitalized research agenda must encompass both local

variation and global commonalities in the impact of adversities, multi-morbidities and their consequences across the life course. We recommend priorities for research — as well as guiding

principles for context-driven, intersectoral, integrative approaches — that will advance knowledge and answer the most pressing local and global mental health questions and needs, while also

promoting a health equity agenda and extending the quality, reach and impact of scientific enquiry. _This article has not been written or reviewed by _Nature_ editors. _Nature_ accepts no

responsibility for the accuracy of the information provided._ MAIN The global mental health landscape has transformed over the past 25 years because of the higher visibility of the burden of

mental health and substance-use disorders1. These disorders comprise 7.4% of global disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) and 22.7% of global years lived with disability (YLDs)2

(Supplementary Information)3. The main contributors worldwide are depression and dysthymia (9.6% of all YLDs); anxiety (3.5% of all YLDs); and schizophrenia, substance-use disorders and

bipolar disorder (just over 2% of all YLDs). Alcohol and substance-use disorders come in second for most of the developing world, more so for southern Africa (drug use) and Eastern Europe

(alcohol)2. The burden of mental health and substance-use disorders is predicted to increase worldwide in coming decades, and the steepest rise can be expected in low- and middle-income

countries (LMICs) as a result of rising life expectancy, population growth and under-resourced health care4. For example, simulation models predict a 130% increase in associated health

burden of alcohol and substance misuse in sub-Saharan Africa by 2050 as a result of population growth and ageing5. As substantial as they are, conventional health metrics do not capture

additional social burdens attached to living with mental illness. Untreated mental health disorders are associated with a high economic burden6. Furthermore, pervasive stigma and human

rights violations compound the suffering associated with these disorders and exacerbate social vulnerabilities7,8,9. As the health, social, economic and human costs of mental and

substance-use disorders become increasingly better documented, political will and multilateral commitments to scale up mental health care in LMICs have grown. The World Health Organization

has introduced a series of policy initiatives that articulate both high-level aspirations and pragmatic guidance for mental health and substance-use services delivery in LMICs. The most

recent, the Global Mental Health Action Plan 2013–2020, challenges member states, partners and the Secretariat to collectively meet ambitious goals by the year 2020, including increasing

mental health care coverage by 20% for severe mental health illness and reducing national suicide rates by 10% (ref. 10). A consideration of the timeline of these landmark events — including

the roll out of a number of key funding and policy initiatives that target the persisting resource gaps — illustrates the substantial momentum in integrating mental health into the broader

global health agenda that has occured over the past few decades (See Supplementary Information). An interactive map, depicting the broad geographical distribution of current, promising

initiatives in global mental health is available at http://www.nimh.nih.gov/about/organization/gmh/global-research-on-mental-health-and-substance-abuse.shtml. Policy and programmatic

initiatives have laid a foundation for strengthened global mental health services by developing an initial consensus scientific agenda that focuses energies and funding on the most crucial

research for building an empirical base. Key funding initiatives have supported research to leverage scarce resources and improve access through task sharing, integration of mental health

care into existing primary health-care infrastructure and enhancement of diagnostic assessment. Increasingly, resources have been allocated to build in-country research capacities and

strengthen collaboration through institutional partnerships11. Complementary graduate-level training programmes in global mental health have also emerged, although mental health specialty

training, as a track, remains relatively under-represented among other global health domains12,13. KEY RESEARCH GAPS AND CHALLENGES The global health burden of mental health disorders is

exacerbated by the growing concurrent problems associated with substance misuse. Substance use and exposure to addictive drugs have chronic and profound effects on neurobehavioural and

neurodevelopmental functions. In LMICs, the socioecology of poverty, malnutrition, political conflicts and poor health systems influence the epidemiology, as well as the adverse outcomes,

that result from substance misuse. Additional challenges associated with co-morbidity stem from its augmentation of clinical burden, through increased risk for relapse, other infectious and

medical complications, and economic hardship and homelessness. In this context, co-morbid substance use and mental illnesses in particular may contribute to increasing health burden. The

prevalence of substance-use disorders has escalated in recent decades, reaching 5.4% of the total disease burden and 9.1% when tobacco use is included14. Individuals with substance-use

disorders are also likely to have other mental health problems, including depression and schizophrenia4,15. Similarly, a large proportion of people with mental illnesses also have

substance-use disorders16,17. Research that investigates the relationship between mental illness and substance-use disorder has yielded mixed findings, with some support for causal

relationships in both directions as well as for shared genetic, environmental, social and cultural risk factors. For example, cannabis use is linked to a risk of developing psychotic

illness18. Conversely, mental illness may increase the risk of substance misuse; individuals may 'self-medicate' with alcohol, tobacco or amphetamines as a means of coping with

distress and negative affects19,20. Some factors, including genetic vulnerabilities, traumatic exposures and stress, may confer risk for both conditions21,22. Diagnosis and treatment of

co-morbid substance misuse and mental health illness remains a significant challenge, particularly in LMICs. The burden of this co-morbidity is further exacerbated by the increased clinical

complexity that stems from resistance to treatment, risk of relapse, vulnerability to other infectious and medical complications, and increased economic hardship and homelessness. The burden

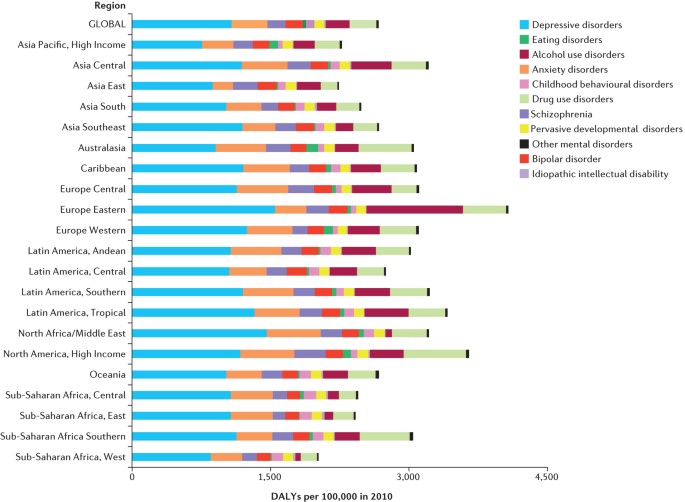

and configuration of risk associated with substance-use disorders and co-morbid mental illness seem to vary across the world (Fig. 1)14. Although alcohol and opioid problems are escalating

in Europe, Africa and Asia, problems associated with amphetamines and cannabis are more prevalent in Asia, North America and Europe. Cocaine use is prevalent in North America and Europe,

whereas misuse of indigenous psychoactive substances is prevalent in other regions, such as the use of khat in parts of Africa and the Middle East and that of coca leaves in South America23.

Notably, existing knowledge gaps may underestimate the impact of substance-use disorders24. The full extent of adverse mental health and social impacts of substance-use disorders such as

alcohol use during pregnancy and fetal alcohol spectrum disorders25 remain incompletely understood. Mental health and substance-use disorders also frequently co-occur with other diseases,

increasing associated morbidity and mortality risk26,27. It is not uncommon for individuals with HIV/AIDS or non-communicable diseases such as hypertension, diabetes and cardiovascular

disease to also have symptoms of depression or anxiety and to use alcohol or other drugs to excess. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder has been associated with risky sexual behaviours

that can result in transmission of HIV/AIDS. These interdependent illnesses stem from common risk factors, such as childhood adversity; and bidirectional influences, such as poor treatment

adherence28 and increased engagement in risky behaviour29,30,31. Growing awareness of the complex interplay between mental illness and the increasing burden of chronic disease globally has

prompted research that examines the effects of depression on adherence to medical treatments and the effects of integrated care — co-treatment of high blood pressure and depression, for

example — on the outcomes of both of the co-occurring illnesses (see for example refs 32,33,34). A life-course approach to risk reduction that takes into account risks that occur in

childhood and early adulthood, and that promotes a healthy lifestyle, and early recognition and treatment of mental and substance-use disorders is essential to curtail the long-term negative

impacts of many preventable health risks. TREATMENT GAP The proportion of people who need, but do not receive care is especially high in LMICs35,36. The inadequate resourcing of mental

health care in LMICs has been widely documented and critiqued. For example, on average less than 3% of public health resources are allocated to specific mental health care in LMICs, with

even less (around 1%) in Africa and Asia37. Most LMICs have far fewer health-care professionals than they need to deliver mental health and substance-use interventions to everyone who needs

them38,39. Scaling up services will require more than training additional psychiatrists, psychologists and psychiatric nurses, however, strategic leveraging of scarce resources will also be

necessary. In particular, task shifting — delegating health-care tasks from specialists to various non-specialist health professionals and other health workers — has shown promise for

certain mental health and substance-use interventions40,41,42,43. In addition, the integration of mental health services into primary health-care delivery settings through community-based

and task-sharing approaches can both help to reduce burden on carers and improve access and the coordination of care. Mental health services and health-system strengthening, and in

particular, task shifting, as well as organization and ways of delivering community-based mental health services in LMICs should be prioritized for research. There is also a substantial gap

in scientific knowledge for preventing and treating mental health and substance-use disorders. In addition, what is currently known is often not applicable to low-resource regions.

Intervention strategies to address substance-use disorders have improved over recent decades, but have had limited success in achieving total recovery and have limited coverage in LMICs15.

Moreover, resources for providing these interventions are constrained or lacking in most LMICs15,24. Models for improving availability and access to effective mental health care emphasize

the integration of both prevention and treatment services within primary care systems. This has been a core approach taken by the WHO Mental Health Gap Action Program (mhGAP)44,45. Most

published clinical trial data on therapeutics for mental health disorders are based on research conducted in high-income countries46,47,48. In the absence of region-specific empirical data,

deployment of these therapeutic strategies in LMICs is a reasonable pragmatic compromise in the short term when informed by local knowledge, and pending rigorous and systematic evaluation.

Local research on clinical effectiveness of these treatments and implementation research on how to deliver these therapies and scale them up are urgently needed. PRIORITIES FOR ADVANCING THE

GLOBAL MENTAL HEALTH AGENDA Our recommendations build on the strong base of empirical evidence and previous consensus statements and reports that have articulated principles, needs and

priorities that should inform a robust research agenda (Table 1). The predominant focus of global mental health research is currently on health services and implementation research, areas

that align well with efforts to close treatment gaps and that must continue to be strengthened. Whereas we regard these contributions as formative and arguably the most pragmatic and exigent

in the short term, they should not pre-empt a more ambitious scope of scientific inquiry that ranges from basic sciences to health policy. Innovation should encompass much more than

strategies to leverage scarce resources lest the scope of progress in the field be consigned to improving the efficiency of old models of care delivery. Instead, complementary and parallel

lines of context-driven research should also aim to advance the scientific understanding of aetiology, population-specific phenotypic variation in presentation and course, and differential

response to therapeutics through promising avenues in neuroscience, biomarkers, genetics and epigenomics. EPIDEMIOLOGY Epidemiological research is crucial to better understand the

differential risk factors and burden of mental health and substance-use disorders across diverse geographical regions and social contexts. Refinement of approaches to diagnostic assessment

that are both locally valid and relatable to global classification is essential to more effective and efficient case identification, particularly in the hands of non-specialists. Such

advances will generate more accurate estimates of health burdens and salient risk factors on which local health policymakers can draw. In addition, research is needed to better define the

health and social impacts of syndemic mental health disorders, substance-use disorders and medical diseases, as well as to understand how social adversities moderate and mediate risk of

onset, severity and course. Such research will inform optimal strategies for prevention, treatment and follow-up care for individuals with these co-morbidities. BASIC SCIENCE RESEARCH The

research agenda to address the global burden of mental health and substance-use disorders should build on recent advances in the field of basic neuroscience, biomarkers, proteomics, and

genetics and epigenetics. For example, research in the past decade has identified molecular and structural markers connected with mental health and substance-use disorders49. These include

protein alterations in the form of upregulation of a 40-amino acid VGF-derived peptide and the downregulation of apoA1 protein in schizophrenia50. Hormonal and physiological alterations in

stress- and appetite-related neuropeptides have also been pursued in the context of addiction and treatment outcome51,52,53. There has also been significant interest in epigenomics and how

it could advance our understanding and use of biomarkers. Epigenomic modifications affect gene expression, and involve multiple molecular steps, including DNA methylation54. In light of

evidence that indicates a role for epigenetic mechanisms in modifying genes that increase propensity for drug use and mental illness, it is important to develop a means by which this

approach could be harnessed to improve the validity and reliability of diagnostic measures as well as to help to tailor interventions to the individual. Research that considers the diversity

of environmental exposures and gene–environment interactions across different settings can advance the utility of these markers to confirm diagnosis and to predict treatment outcome.

Furthermore, such markers may be useful in identifying those at high risk so that measures can be applied to prevent initial risk or onset, or slow down or prevent progression towards

psychopathology. The use of such approaches should also parallel the development of conceptual models to guide understanding of the complex, multidimensional aetiology of mental health and

substance-use disorders. To that end, global research that focuses on mental health and substance-use disorders should take into account how genetics and exposure to environmental toxins

interact with social, cultural and environmental conditions to moderate the risk of these disorders. HEALTH DELIVERY AND IMPLEMENTATION RESEARCH Four out of the top five research priorities

identified in the grand challenges statement — developed by a consortium of researchers, advocates and clinicians with funding from the US National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) and the

Global Alliance for Chronic Diseases — fall in the domain of enhancing the quality of, and access to, mental health care55. This call to invest in health services and implementation research

is in response to identified treatment gaps as well as their numerous antecedents, such as weak health systems, shortfalls in human and financial resources, and social structural barriers

to care. There is ample evidence for science-based care and the integration of mental health services into primary health care. However, we still lack crucial knowledge on how best to

disseminate and implement evidence-based mental health interventions in resource-poor contexts, including those characterized by the extreme social adversities associated with political

conflict, displacement and destitution. Future research is therefore necessary to rigorously evaluate and optimize effectiveness of task sharing, integration of mental health into primary

care, and deployment of the mhGAP algorithms at larger scale and across diverse social settings41,56. Key strategies for expanding access to high-quality mental health care in LMICs come

from models that are successful in leveraging scarce resources in other clinical domains. However, challenges unique to care delivery for mental health and substance-use disorders warrant

special attention and innovation. These include how to improve diagnostic assessment and population health surveillance, given the heterogeneous and sometimes opaque presentations of signs

and symptoms across diverse social and cultural contexts57,58; how to address the social and cultural factors, especially stigma, that hinder access to care and may prevent patients with

mental illnesses and substance-use problems from using the resources available for prevention and treatment; how to mitigate social vulnerabilities, such as poverty and gender-based violence

that elevate risk of mental disorders, while building on sociocultural resources that promote coping and resilience; how to develop coordinated approaches to strategic preventive

interventions, monitoring and targeted treatments over the life course and across disorders, given developmental trajectories of mental health and substance-use disorders, and their harmful

symbiosis with other chronic conditions and vulnerabilities; and how to rapidly scale up effective interventions to close the treatment gap in resource constrained environments59,60,61.

Priorities for global mental health research resonate with the global health agenda, with its focus on reducing health burdens62. In this respect, a globalizing framework aimed at developing

approaches that are effective when scaled up and implemented across geographically and socially diverse settings and populations reflect pragmatic goals of responding to pressing needs. We

emphasize, however, that closing the prevailing treatment gaps for mental health and substance-use disorders will also depend on fortifying scientific inquiry so that we can understand the,

sometimes remarkable, local variation in manifestation and course of mental disorders63. TRANSLATIONAL AND HEALTH-POLICY RESEARCH Ensuring that populations receive high-quality care that

improves mental health is the purview of policymakers. Shaping sound public policies that are based on up-to-date research can be challenging, but promising examples exist. An experimental

housing policy called Moving to Opportunity found that moving from a high-poverty to a lower-poverty neighbourhood improved adult physical and mental health and subjective wellbeing over

10–15 years, despite no change in average economic status64. Moving to Opportunity was able to capitalize on the fact that public policy decisions are interconnected — it is not just health

policies that influence mental health, substance use and other public health outcomes, but also economic, housing and criminal justice policies, among others65. Rapid growth in mental health

and substance-use research over the past decade, as well as appeals from researchers and advocates to apply the findings in policy and practice have not yet bridged the divide between what

is known and what is done66,67. The intricacies of ensuring evidence-based health policy are not entirely understood68, but a few effective practices are being used. Advocacy organizations

such as the National Alliance on Mental Illness have become trusted sources of digestible research findings69. Carefully planned links between researchers and decision makers — an approach

increasingly encouraged by funders of mental health and substance-use research — can also be effective69. Such links often involve collaboration among researchers, government agencies,

advocates and provider institutions to synchronize research activities with policies, health-care demands and community priorities, and to engage key stakeholders in the identification of

pressing research questions and the use of study findings. In this way, policymakers have become partners in the research enterprise, helping researchers to understand what information is

needed for developing or updating policies, making investment decisions, expanding access to care, improving care quality and monitoring system-level change over time. The long-term goal is

that these partnerships will mobilize political will, inform policy development, and shed light on the essentials of shaping science-informed mental health and substance-use policies.

Inclusion of mental health as an explicit priority in the post-2015 development agenda (such as that included in the UN Open Working Group on Sustainable Development Goals, 2015;

https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/7891TRANSFORMING%20OUR%20WORLD.pdf) provides an opportunity to mobilize the requisite political will and resources at several levels

so that this ambitious agenda for research and capacity building can be realized. Lessons learned from the positive health impact as a result of Millennium Development Goals 4, 5 and 6

illuminate how multisector and multilevel cohesion of effort and commitments are powerful levers for advancing health in low-resource settings, and an opportunity for the broad community of

stakeholders and advocates to improve care for individuals living with mental health and substance-use disorders. COLLABORATIVE CAPACITY BUILDING New commitments and additional resources

will be needed to rapidly cultivate the in-country research capacity needed to respond to the global disease burden of mental health and substance-use disorders70. The most culturally

sensitive, scientifically and ethically sound, and locally relevant research requires investigators who best understand and live among the populations that they study. Funding initiatives

such as the Fogarty International Center's Global Brain and Nervous System Disorders Across the Lifespan programme (http://www.fic.nih.gov/Programs/Pages/Brain-Disorders.aspx), the

NIMH's Collaborative Hubs for International Research in Mental Health (http://www.nimh.nih.gov/about/organization/gmh/globalhubs/index.shtml) as well as Grand Challenges Canada's

Global Mental Health granting programme (http://www.grandchallenges.ca/grand-challenges/global-mental-health/) that explicitly structure research capacity building into grant requirements,

provide exemplary platforms to test and ultimately to systematize innovative strategies for training, mentorship and building a research culture and other infrastructural support for

research in LMICs. In addition, collaborative capacities to advance the mental health and substance-use research agenda must be developed. Capacity building in knowledge management is also

integral to packaging accrued evidence so that it is accessible to policymakers and mental health technology specialists in LMICs. Platforms for knowledge sharing (for example, the Mental

Health Innovation Network, http://mhinnovation.net/; and GHD Online, http://www.ghdonline.org/) can promote scientific discovery and help to harmonize the mental health and substance-use

disorder research goals, processes and tools, and to catalyse the translational potential of research to policy and programmes71. Moreover, these platforms are needed to build and

consolidate the community of advocates, consumers, investigators, clinicians and policymakers united in their commitment to mitigate the suffering associated with mental health and

substance-use disorders, eliminate their attendant stigma, diminish their social and economic burdens, and erase the social and health disparities perpetuated by poor access to high-quality

mental health care. CONCLUSIONS The formidable and rising health, economic and social burdens associated with mental health and substance-use disorders call for the prioritization of

research that can inform a global response — through the development and enhancement of preventive and therapeutic strategies, health-system strengthening and policymaking — to alleviate

suffering and stem the associated economic and social consequences of unmet needs. Indeed, the potential synergies among breakthroughs in basic neuroscience, epidemiological methods and

implementation science, as well as the mobilization of resources and political will have generated optimism and catalysed a commitment to act among policymakers, advocates and the scientific

community. Although the increase in mental health research initiatives over the past two decades are encouraging for the future challenges remain and patterns of progress have been

inconsistent. We find, for example, that although response to the growing burden of depression in LMICs has led to an increase in the number of studies on effectiveness of treatments,

delivery methods and task shifting to provide access to care for all populations, we do not see this same trajectory of efforts to address substance-use disorders. This occurs with the

background of growing substance-use problems globally. Approaches to address substance-use disorders in LMICs are still limited, fragmented and not well vetted scientifically or culturally.

On an optimistic note, the draft Social Development Goals to be passed by the UN General Assembly in September 2015 recognise mental health as integral to health and mental health is

explicitly included within universal health coverage; in addition, the UN General Assembly will hold a special session on drugs in 2016. These developments have symbolic and substantive

importance, and auger well for mental health within the Global Health agenda in the coming years. REFERENCES * Becker, A. E. & Kleinman, A. In _Psychiatry: Past, Present, and Prospect_

(eds Bloch, S., Green, S. & Holmes, J.) (Oxford Univ. Press, 2014). Google Scholar * Murray, C. J. L. et al. Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21

regions, 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. _Lancet_ 380, 2197–2223 (2012). PubMed Google Scholar * Vos, T. et al. Years lived with disability

(YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. _Lancet_ 380, 2163–2196 (2012). Article PubMed PubMed

Central Google Scholar * Whiteford, H. A. et al. Global burden of disease attributable to mental and substance use disorders: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010.

_Lancet_ 382, 1575–1586 (2013). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Charlson, F. J., Diminic, S., Lund, C., Degenhardt, L. & Whiteford, H. A. Mental and substance use disorders in

sub-Saharan Africa: predictions of epidemiological changes and mental health workforce requirements for the next 40 years. _PLoS ONE_ 9, e110208 (2014). Article ADS PubMed PubMed Central

CAS Google Scholar * Bloom, D. E. et al. _The Global Economic Burden of Non-communicable Diseases_ (World Economic Forum and the Harvard School of Public Health, 2011). Google Scholar *

Kleinman, A. Global mental health: a failure of humanity. _Lancet_ 374, 603–604 (2009). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Drew, N. et al. Human rights violations of people with mental and

psychosocial disabilities: an unresolved global crisis. _Lancet_ 378, 1664–1675 (2011). Article PubMed Google Scholar * World Health Organization. Mental health and development: Targeting

people with mental health conditions as a vulnerable group http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/89966/1/9789241506021_eng.pdf (WHO, 2010). * World Health Organization. Global Action

Plan for the prevention and control of NCDs 2013–2020 http://www.who.int/nmh/events/ncd_action_plan/en/ (WHO, 2013). * Fricchione, G. L. et al. Capacity building in global mental health:

professional training. _Harv. Rev. Psych._ 20, 47–57 (2012). Article Google Scholar * Kerry, V. B. et al. US medical specialty global health training and the global burden of disease. _J.

Glob. Health_ 3, 020406 (2013) Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Tsai, A. C. et al. Global health training in US graduate psychiatric education. _Acad. Psychiatry_ 38,

426–432 (2014). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * World Health Organization. _ATLAS on substance use. Resources for the prevention and treatment of substance use disorders_

(WHO, 2010). * Volkow, N. D. The reality of comorbidity: depression and drug abuse. _Biol. Psychiatry_ 56, 714–717 (2004). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Kessler, R. C. The epidemiology

of dual diagnosis. _Biol. Psychiatry_ 56, 730–737 (2004). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Wright, S., Gournay, K., Glorney, E. & Thornicroft, G. Dual diagnosis in the suburbs:

prevalence, need, and in-patient service use. _Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol._ 35, 297–304 (2000). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Moore, T. H. et al. Cannabis use and risk of

psychotic or affective mental health outcomes: a systematic review. _Lancet_ 370, 319–328 (2007). Article PubMed Google Scholar * van Emmerik-van Oortmerssen, K. et al. Prevalence of

attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in substance use disorder patients: a meta-analysis and meta-regression analysis. _Drug Alcohol Depend._ 122, 11–19 (2012). Article PubMed Google

Scholar * Khantzian, E. J. The self-medication hypothesis of substance use disorders: a reconsideration and recent applications. _Harv. Rev. Psychiatry_ 4, 231–244 (1997). Article CAS

PubMed Google Scholar * Quello, S. B., Brady, K. T. & Sonne, S. C. Mood disorders and substance abuse disorders: a complex comorbidity. _Sci. Practice Perspect._ 3, 13–24 (2005).

Article Google Scholar * al'Absi, M. _Stress and Addiction: Biological and Psychological Mechanisms_ (Academic, 2007). Google Scholar * UNODC. _World Drug Report 2014_ (United

Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2014). * Degenhardt, L., Whiteford, H. & Hall, W. D. The Global Burden of Disease projects: What have we learned about illicit drug use and dependence

and their contribution to the global burden of disease? _Drug Alcohol Rev._ 33, 4–12 (2014). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Balachova, T. et al. Women's alcohol consumption and risk

for alcohol-exposed pregnancies in Russia. _Addiction_ 107, 109–117 (2012). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Edmondson, D. et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder prevalence and risk of

recurrence in acute coronary syndrome in patients: a metanalytic review. _PloS ONE_ 7, e38915 (2012). Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Lee, A. A., McKibbin, C.

L., Bourassa, K. A., Wykes, T. L. & Kitchen Andren, K. A. Depression, diabetic complications and disability among persons with comorbid schizophrenia and type 2 diabetes.

_Psychosomatics_ 55, 343–351 (2014). Article PubMed Google Scholar * World Health Organization & Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation. _Integrating the Response to Mental Disorders and

Other Chronic Diseases in Health Care Systems_ (WHO, 2014). * Mimiaga, M. J. et al. The effect of psychosocial syndemic production on 4-year HIV incidence and risk behavior in a large cohort

of sexually active men who have sex with men. _J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr._ 68, 329–336 (2014). Article Google Scholar * Vassileva, J. et al. Impaired decision-making in psychopathic

heroin addicts. _Drug Alcohol Depend._ 86, 287–289 (2007) Article PubMed Google Scholar * Sung, Y. H. et al. Decreased frontal N-acetylaspartate levels in adolescents concurrently using

both methamphetamine and marijuana. _Behav. Brain Res._ 246, 154–161 (2013). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * National Institute of Mental Health. _Grand Challenges in

Global Mental Health: Integrating Mental Health into Chronic Disease Care Provision in Low- and Middle-Income Countries (R01)_

http://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/rfa-files/RFA-MH-13-040.html (NIH, 2013). * Grimsrud, A., Stein, D. J., Seedat, S., Williams, D. & Myer, L. The association between hypertension and

depression and anxiety disorders: results from a nationally-representative sample of South African adults. _PLoS ONE_ 4, e5552 (2009). Article ADS PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google

Scholar * Wu, C. Y., Prosser, R. A. & Taylor, J. Y. Association of depressive symptoms and social support on blood pressure among urban African American women and girls. _J. Am. Acad.

Nurse Pract._ 22, 694–704 (2010). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Wang, P. S. et al. Use of mental health services for anxiety, mood, and substance disorders in 17

countries in the WHO world mental health surveys. _Lancet_ 370, 841–850 (2007). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Demyttenaere, K. et al. Prevalence, severity, and unmet

need for treatment of mental disorders in the World Health Organization world mental health surveys. _J. Am. Med. Assoc._ 291, 2581–2590 (2004). Article Google Scholar * Copeland, J.,

Thornicroft, G., Bird, V., Bowis, J. & Slade, M. Global priorities of civil society for mental health services: findings from a 53 country survey. _World Psychiatry_ 13, 198–200 (2014).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Saxena, S., Thornicroft, G., Knapp, M. & Whiteford, H. Resources for mental health: scarcity, inequity, and inefficiency. _Lancet_ 370,

878–889 (2007). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Bruckner, T. A. et al. The mental health workforce gap in low- and middle-income countries: a needs-based approach. _Bull. World Health

Organ._ 89, 184–194 (2011). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Araya, R., Flynn, T., Rojas, G., Fritsch, R. & Simon, G. Cost-effectiveness of a primary care treatment program for

depression in low-income women in Santiago, Chile. _Am. J. Psychiatry_ 163, 1379–1387 (2006). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Mendenhall, E. et al. Acceptability and feasibility of using

non-specialist health workers to deliver mental health care: stakeholder perceptions from the PRIME district sites in Ethiopia, India, Nepal, South Africa, and Uganda. _Soc. Sci. Med._ 118,

33–42 (2014). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Patel, V. et al. Lay health worker led intervention for depressive and anxiety disorders in India: impact on clinical and

disability outcomes over 12 months. _Br. J. Psychiatry_ 199, 459–466 (2011) Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Rahman, A., Malik, A., Sikander, S., Roberts, C. & Creed,

F. Cognitive behavior therapy-based intervention by community health workers for mothers with depression and their infants in rural Pakistan: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. _Lancet_

372, 902–909 (2008). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * World Health Organization. _Closing the Gap in a Generation: Health Equity Through Action on the Social Determinants

of Health_ (WHO, 2008). * World Health Organization. _WHO mhGAP Intervention Guide for Mental, Neurological, and Substance use Disorders in Non-Specialized Health Settings_

http://www.who.int/mental_health/publications/mhGAP_intervention_guide/en/index.html (WHO, 2010) * Patel, V. & Kim, Y.-R. Contribution of low- and middle-income countries to research

published in leading psychiatry journals, 2002-2004. _Br. J. Psychiatry_ 190, 77–78 (2007). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Razzouk, D. et al. Scarcity and inequity of mental health

research resources in low-and-middle-income countries: a global survey. _Health Policy_ 94, 211–220 (2010). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Kieling, C. et al. Child and adolescent mental

health worldwide: evidence for action. _Lancet_ 378, 1515–1525 (2011). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Schwarz, E. & Bahn, S. The utility of biomarker discovery approaches for the

detection of disease mechanisms in psychiatric disorders. _Br. J. Pharmacol._ 153, S133–S136 (2008). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Huang, J. T. et al. Independent

protein-profiling studies show a decrease in apolipoprotein A1 levels in schizophrenia CSF, brain and peripheral tissues. _Mol. Psychiatry_ 13, 1118–1128 (2008). Article CAS PubMed Google

Scholar * al'Absi, M., Hatsukami, D. & Davis, G. Attenuated adrenocorticotropic responses to stress predict early relapse. _Psychopharmacology_ 181, 107–117 (2005). Article CAS

PubMed Google Scholar * al'Absi, M., Lemieux. A. & Nakajima, M. Peptide YY and ghrelin predict craving and risk for relapse in abstinent smokers. _Psychoneuroendocrinology_ 49,

253–259 (2014). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Karpyak, V. M. et al. Genetic markers associated with abstinence length in alcohol-dependent subjects treated with

acamprosate. _Transl. Psychiatry_ 4, e462 (2014) Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Peedicayil, J. Epigenetic biomarkers in psychiatric disorders. _Br. J. Pharmacol._ 155, 795–796

(2008). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Collins, P. Y., Patel, V. & Joestl, S. S. Grand challenges in global mental health. _Nature_ 475, 27–30 (2011). Article

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * van Ginneken, N. et al. Non-specialist health worker interventions for mental health care in low-and middle-income countries. _Cochrane

Database Syst. Rev._ 11, CD009149 (2013). Google Scholar * Kohrt, B. A. et al. Cultural concepts of distress and psychiatric disorders: literature review and research recommendations for

global mental health epidemiology. _Int. J. Epidemiol._ 43, 365–406 (2014). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Jacob, K. S. & Patel, V. Classification of mental disorders: a global

mental health perspective. _Lancet_ 383, 1433–1435 (2014). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Chisholm, D. et al. Scale up services for mental disorders: a call for action. _Lancet_

370, 1241–1252 (2007). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Eaton, J. et al. Scale up of services for mental health in low-income and middle-income countries. _Lancet_ 378, 1592–1603

(2011). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Lund, C. et al. Mental health is integral to public health: a call to scale up evidence-based services and developmental health research. _S. Afr.

Med. J._ 98, 444 (2008). PubMed Google Scholar * Patel, V. Why mental health matters to global health. _Transcult. Psychiatry_ 51, 777–789 (2014). Article PubMed Google Scholar * de

Jong, J. T. Challenges of creating synergy between global mental health and cultural psychiatry. _Transcult. Psychiatry_ 51, 806–828 (2014). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Ludwig, J. et

al. Neighborhood effects on long-term well-being of low-income adults. _Science_ 337, 1505–1510 (2012) Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Ovretveit, J. In:

_Managing for Health_ (ed. Hunter, D. J.) 129–148 (Routledge, 2007). Book Google Scholar * Mackenzie, J. _Global Mental Health from a Policy Perspective: A Context Analysis_ (Overseas

Development Institute, 2014). Google Scholar * Phillips, M. R. Can China's new mental health law substantially reduce the burden of illness attributable to mental disorders? _Lancet_

381, 1964–1966 (2013). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Goldner, E. M., Jenkins, E. K. & Fischer, B. A narrative review of recent developments in knowledge translation and implications

for mental health care providers. _Can. J. Psychiatry_ 59, 160–169 (2014). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Dobbins, M. et al. A randomized controlled trial evaluating the

impact of knowledge translation and exchange activities. _Implement Sci._ 4, 61 (2009). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Thornicroft, G., Cooper, S., Van Bortel, T.,

Kakuma, R. & Lund, C. Capacity building in global mental health research. _Harv. Rev. Psychiatry_ 20, 13–24 (2012). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Mello, M. M. et al.

Preparing for responsible sharing of clinical trial data. _N. Engl. J. Med._ 369, 1651–1658 (2014). Article CAS Google Scholar Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The authors thank J.

Dewit, A. Garton, Y. Bodenstein and J. Nguyen at the National Institute of Mental Health for construction of the interactive map. M. A. was supported in part by the following grants:

R01DA016351 and R01DA027232, and a BRAIN R21 grant (R21DA024626). F. B. was supported in part by Grand Challenges Canada Grant GMH 0094-04. We are grateful to B. Good for his insightful

review and suggestions. AUTHOR INFORMATION AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Makerere University School of Public Health, PO Box 7072, Kampala, Uganda Florence Baingana * Duluth Medical Research

Institute (DMRI), University of Minnesota Medical School, 311-1035 University Drive, Duluth, 55812, Minnesota, USA Mustafa al'Absi * Department of Global Health and Social Medicine,

Harvard Medical School, 641 Huntington Avenue, Boston, 03115, Massachusetts, USA Anne E. Becker * Office for Research on Disparities & Global Mental Health, National Institute of Mental

Health, 6001 Executive Boulevard, Room 7207, Bethesda, 20892, Maryland, USA Beverly Pringle Authors * Florence Baingana View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed

Google Scholar * Mustafa al'Absi View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Anne E. Becker View author publications You can also search for

this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Beverly Pringle View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to Florence

Baingana. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS The authors declare no competing financial interests. Financial support for publication has been provided by the Fogarty International

Center. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE 1 (PDF 70 KB) RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images

or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included

under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0 Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Baingana, F., al'Absi, M., Becker, A. _et al._ Global research challenges and

opportunities for mental health and substance-use disorders. _Nature_ 527, S172–S177 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature16032 Download citation * Published: 18 November 2015 * Issue Date:

19 November 2015 * DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nature16032 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a

shareable link is not currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative