Play all audios:

ABSTRACT BACKGROUND The aim of the study was to examine correlates of sleep and assess its associations with weight status and related behaviors. METHODS Data were collected in 2015–2017 for

3298 children aged 6–17 years and their parents in 5 Chinese mega-cities. One thousand six hundred and ninety-one children with measured weight, height, and waist circumference in ≥2

surveys were included for longitudinal data analyses. Sleep and behaviors were self-reported. RESULTS Cross-sectional data analyses found that older (_β_ = −0.29, 95% CI: −0.32, −0.27) and

secondary school children (_β_ = −1.22, 95% CI: −1.31, −1.13) reported shorter sleep than their counterparts. Children with ≥college-educated (vs <college) fathers (_β_ = 0.17, 95% CI:

0.04, 0.31) or mothers (_β_ = 0.16, 95% CI: 0.04, 0.29) reported longer sleep. Longer sleep was longitudinally associated with less sugar-sweetened beverage intake (_β_ = −0.12 days/h sleep,

95% CI: −0.20, −0.03), more healthy snacks intake (_β_ = 0.13 days/h sleep, 95% CI: 0.02, 0.25) and having breakfast (_β_ = 0.07 days/h sleep, 95% CI: 0.04, 0.11), and shorter total screen

time (_β_ = −0.22 h/h sleep, 95% CI: −0.65, −0.21) and surfing the internet/computer time (_β_ = −0.06 h/h sleep, 95% CI: −0.09, −0.04) among all children. Longer sleep reduced the risk of

central obesity (OR = 0.46, 95% CI: 0.25, 0.85) for girls. CONCLUSIONS Sleep among urban Chinese children varies by demographic factors. Longer sleep is associated with healthier

weight-related behaviors and lower central obesity risk. IMPACT * Longer sleep was observed in younger, primary school children and children with college-educated parents. * Longer sleep

increased healthier weight-related behaviors and reduced general and central obesity risk. * Provides data on the correlates of sleep duration of children. * Gives insights on longitudinal

relationships of sleep duration with weight-related behaviors and obesity risk. * Findings help inform sleep interventions to increase sleep duration to prevent childhood obesity and

unhealthy weight-related behaviors in urban settings of developing countries. You have full access to this article via your institution. Download PDF SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS

ASSOCIATIONS OF MULTIPLE SLEEP DIMENSIONS WITH OVERALL AND ABDOMINAL OBESITY AMONG CHILDREN AND ADOLESCENTS: A POPULATION-BASED CROSS-SECTIONAL STUDY Article 13 May 2023 EPIDEMIOLOGY OF

ACCELEROMETER-BASED SLEEP PARAMETERS IN US SCHOOL-AGED CHILDREN AND ADULTS: NHANES 2011–2014 Article Open access 10 May 2022 SLEEP ONSET, DURATION, OR REGULARITY: WHICH MATTERS MOST FOR

CHILD ADIPOSITY OUTCOMES? Article 12 May 2022 INTRODUCTION Sleep is an essential behavior for optimal child health.1 However, a global, secular decline of 0.75 min per year in child sleep

duration has been observed over the past 100 years with greatest rates of decline seen in Asia.2 In China, >15% of school-aged children are estimated to not get enough sleep.3 This is in

part attributable to the high educational aspirations and demands placed on Chinese children by schools and parents due to the rapid social changes and implementation of the one-child policy

since the 1980s; the atmosphere of heightened academic competition and expectation often leaves children more vulnerable to insufficient sleep.2,3 The prevalence of insufficient sleep is

even higher in mega-cities in China. In 2010, 62.9% of children aged 9–18 years were reported to sleep ≤8 h per day in Chinese urban areas;4 these estimates have not been updated despite

continued growth. Indeed, mega-cities, which have led China’s economic development over the past decades, are where the fastest changes in environment and urbanization in China have

occurred. Closer examination of change in sleep duration and its potential determinants among children in these locales are critical for understanding the sleep health of Chinese urban

children. Sleep duration in children may be influenced by child and parental socio-demographic factors. For example, older ages5 and higher school grades6 have been found to be risk factors

for shorter sleep duration. There exist contradictory findings as to whether boys or girls sleep more.7 Parental education level has also been shown to be associated with children’s sleep

duration.7 However, factors impacting children’s sleep duration have not been well studied in Chinese mega-cities. Insufficient sleep may increase the risk of overweight and obesity8 and

engaging in unhealthy weight-related behaviors [e.g., consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs) and using screens].9 In Chinese children, the prevalence of all these factors was very

high. For example, the prevalence of overweight and obesity was 28.2% in 2014,10,11 66.6% of Chinese children consumed SSBs weekly,12 and 21.6% spent ≥2 h/day using screens.13 While several

cross-sectional studies have observed associations between shorter sleep duration with increased overweight and obesity risk14 and frequency of unhealthy behaviors in children,9 no large

prospective studies have examined how children’s sleep duration may affect weight status and related behaviors in Chinese mega-cities.8 To fill these knowledge gaps, this study utilized

longitudinal data collected from five mega-cities (city population >8 million) in China in 2015–2017 and examined (1) overall and sex-specific correlates of children’s sleep duration and

(2) overall and sex-specific associations of children’s sleep duration with body weight status and related behaviors. Shorter sleep duration was hypothesized to increase risk of overweight

and obesity (including central obesity) and be associated with more unhealthy weight-related behaviors. METHODS AND MATERIALS ETHICS STATEMENT This study was conducted in compliance with the

Declaration of Helsinki and with the approval of the ethics committees of the State University of New York at Buffalo and the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention in China.

Informed consent was obtained from a parent and/or legal guardian for children’s participation in this study. STUDY DESIGN AND PARTICIPANTS The Childhood Obesity Study in China Mega-cities

(COCM) was a U.S. NIH-funded longitudinal study aiming to examine the etiology of childhood obesity and chronic diseases in China. This study uniquely captures health trends related to

lifestyle behaviors changes occurring at the forefront of China’s economic growth. Initially, four major cities across China were included in 2015 at baseline: Beijing in the North, the

capital; Shanghai in the Southeast, China’s largest and most economically developed city; Nanjing in the Southeast, China’s old capital before 1949 and capital of Jiangsu province; and Xi’an

in the Northwest, a dynastic capital of China and capital of Shanxi province. In 2016, Chengdu, in the Southwest and capital of Sichuan province, was added. A cluster randomized sampling

design was applied. The sampling method has been described in detail in previous publications.15,16 This study used data collected annually in 2015–2017 via Chinese language surveys on child

and parental characteristics, sleep duration, and weight and related behaviors. This study utilized an open cohort design so some students completed the survey only once while others

completed the survey multiple times, as students graduated, and new students also joined. For cross-sectional data analyses, we used each child’s first observation from pooled data during

2015–2017 (_n_ = 3298; mean age ± SD: 11.5 ± 2.0 years, range: 6.5–17.5 years). For longitudinal analyses, children were included if their eating and drinking behaviors, screen time

behaviors, body weight and height, and/or waist circumference had been recorded at least twice in the 2015–2017 period (_n_ = 1691, mean age ± SD: 11.2 ± 1.9 years, range: 6.5–16 years). KEY

STUDY VARIABLES AND MEASUREMENTS OUTCOME VARIABLES OVERWEIGHT AND OBESITY Students’ body mass index was calculated as weight (kg) divided by height squared (m2). Height was measured using

Seca 213 Portable Stadiometer Height-Rods (Seca China, Zhejiang, China) with a precision of 0.1 cm. Body weight was measured using Seca 877 electronic flat scales (Seca China, Zhejiang,

China) with a precision of 0.1 kg. Height and weight were measured by trained health professionals. Overweight and obesity were defined using age- and sex-specific BMI cutoff points issued

by the National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China.17 CENTRAL OBESITY Waist circumference was measured using a non-stretchable tape with a precision of 0.1 cm. Central

obesity was defined as having a waist-to-height ratio ≥0.4818 and taken as a dichotomous dependent variable in mixed-effects models. EATING BEHAVIORS Children were asked to report average

(in days) weekly consumption of the following during the previous 3 months: breakfast, SSBs (common examples were listed), and healthy snacks (i.e., fruits, eggs, milk, other dairy and dairy

products, beans and beans products, and nuts). A healthy snacks composite score was calculated by summing and averaging the consumption frequencies of the six specified snacks. These three

eating behaviors were treated as continuous dependent variables in mixed-effects models. SCREEN TIME Children were asked to self-report total time spent per week using screens in general

(e.g., cell phones, iPads, computers, and TV, and excluding time related to school or studying) and time spent per day specifically surfing the internet/using the computer or watching TV.

For these latter two behaviors, participants were asked how many times they used the computer/internet or watched TV in the past 7 days and about how long they spent doing so each time. The

three screen time variables were used as continuous dependent variables in mixed-effects models. EXPOSURE VARIABLES SLEEP DURATION Sleep was assessed by one question “On average, how many

hours and minutes did you sleep (including naps) on a typical day during the past 7 days?” This item has been used extensively in previous studies among children in China.19,20 The reported

duration was categorized according to sex-specific sleep duration cutoffs previously used in children,21 given age-related shifts in children’s sleep needs and circadian rhythms.22 For

children aged <10 years, the recommended sleep duration, shorter duration, and shortest duration were ≥10 h/day, 8–10 h/day, and <8 h/day, respectively. For children aged ≥10 years,

the recommended sleep duration, shorter duration, and shortest duration were ≥9 h/day, 7–9 h/day, and <7 h/day, respectively.22 The shorter and shortest sleep duration were defined as

insufficient sleep. Sleep was used as both a continuous (h and min and a categorical variable in mixed-effects models. COVARIATES A host of variables were included in mixed-effects models

predicting students’ weight status and related behaviors. The potential associations of these variables with children’s sleep duration were also examined. These variables included: age (in

years), sex, city of residence (Beijing, Shanghai, Nanjing, Xi’an, or Chengdu), baseline weight status, baseline eating and drinking behaviors, baseline screen times, school level (primary

or secondary), and highest paternal and maternal education levels (≤middle school, high and vocational schools, or ≥college). STATISTICAL ANALYSIS First, descriptive statistics were

calculated. Chi-square tests (for categorical variables) and _t_ tests (for continuous variables) were conducted to test for sex differences in children and parental characteristics using

pooled, cross-sectional data. Second, linear and logistic mixed-effects models were used to examine the following: (1) potential child and parental correlates of children’s sleep duration

via pooled, cross-sectional data, including age, sex, school type, city of residence, children’s primary caregiver, and highest paternal and maternal education; and (2) the longitudinal

associations of sleep duration with children’s weight status and related behaviors. Linear models were used for sleep duration as a continuous variable and logistic for sleep as a binary

variable. Models adjusted for random effects arising from cities of residence and schools, as well as other covariates including age and sex, baseline eating and drinking behaviors, baseline

weight status, and paternal and maternal education levels. Sex-stratified analyses were conducted to explore potential differences in these associations. In such analyses, all covariates

except for sex were adjusted for. Potential interaction effects of sleep duration and age (both mean-centered) on eating and drinking behaviors, screen time, and weight status were also

examined and tested in linear or logistic mixed-effects models. Effect sizes were presented either as beta coefficients with standard error or odds ratios (ORs) with a 95% confidence

interval (95% CI). Analyses were performed using Stata 14 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). Statistical significance was set at _p_ < 0.05. RESULTS CHARACTERISTICS OF THE CHILDREN

Children self-reported an average sleep duration of 8.5 h/day. The prevalence of insufficient sleep duration was 56.9%; no significant sex differences were found. The combined prevalence of

overweight/obesity and central obesity were 31.4 and 2.3%, respectively. Boys were more likely to have overweight/obesity (39.2 vs 23.4%, _p_ < 0.001) and centrally obesity (3.1 vs 1.4%,

_p_ = 0.001) than girls. Average total screen time was 6.3 h/week overall. Boys reported longer total screen time than girls (7.1 vs 5.5 h/week, _p_ < 0.001) and also spent more time

surfing the internet/using the computer (0.6 vs 0.4 h/day, _p_ < 0.001) and watching TV (0.6 vs 0.4 h/day, _p_ < 0.001) (Table 1). CROSS-SECTIONAL DATA ANALYSIS: POSSIBLE CORRELATES OF

SLEEP DURATION Shorter sleep duration was observed with age (_β_ = −0.29, 95% CI: −0.32, 0.27) and in secondary school children (_β_ = −1.22, 95% CI: −1.31, −1.13); no sex differences were

found. All adolescents in Shanghai (_β_ = 0.29, 95% CI: 0.15, 0.44), Nanjing (_β_ = 0.20, 95% CI: 0.04, 0.36), Xi’an (_β_ = 0.21, 95% CI: 0.05, 0.36), and Chengdu (_β_ = 0.20, 95% CI: 0.04,

0.36) reported longer sleep duration than children living in Beijing, especially boys. Compared to children whose primary caregivers were their mothers, those primarily taken care of by

other caregivers reported longer sleep duration among all children (_β_ = 0.49, 95% CI: 0.11, 0.87) and boys (_β_ = 0.51, 95% CI: 0.03, 0.99). Regarding parental education, in the analyses

of all children, those with fathers (_β_ = 0.17, 95% CI: 0.04, 0.31) or mothers (_β_ = 0.16, 95% CI: 0.04, 0.29) with ≥college education, longer sleep duration was reported compared to

children of fathers or mothers, respectively, with lower education. By sex, longer sleep duration was observed in boys (_β_ = 0.19, 95% CI: 0.001, 0.37) whose fathers attained ≥college

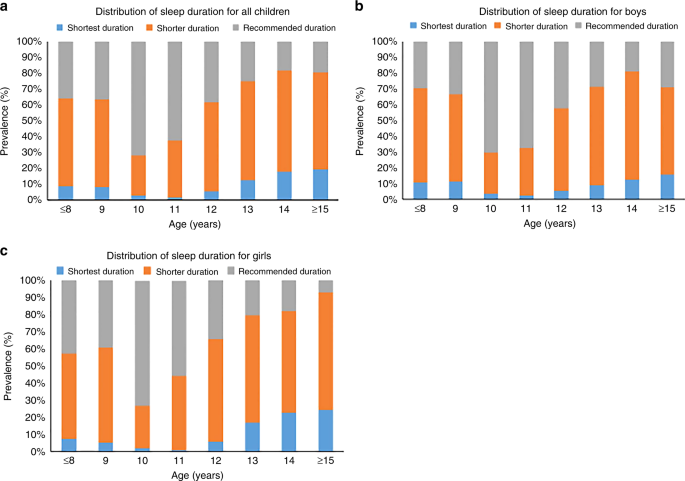

education and in girls (_β_ = 0.23, 95% CI: 0.04, 0.41) whose mothers attained ≥college education vs respective parents with lower educational attainment (Table 2). Trend analyses of sleep

duration with age found the prevalence of insufficient sleep to increase in children between ages 6 and 17 years, especially after age 10 years. By sex, the prevalence of insufficient sleep

increased more rapidly in girls (Fig. 1). LONGITUDINAL DATA ANALYSIS: ASSOCIATIONS OF SLEEP DURATION WITH CHILDREN’S EATING AND DRINKING BEHAVIORS First, we treated sleep duration as a

continuous variable in linear mixed-effects models. Among all children, longer sleep duration was associated with more frequent consumption of healthy snacks (_β_ = 0.13, 95% CI: 0.02, 0.25)

and less frequent consumption of SSBs (_β_ = −0.12, 95% CI: −0.20, −0.03) after adjusting for covariates, such as age and sex. Sex-stratified analysis found longer sleep duration to be

associated with less SSB consumption (_β_ = −0.15, 95% CI: −0.28, −0.02) in boys and more frequent consumption of healthy snacks (_β_ = 0.17, 95% CI: 0.001, 0.34) and breakfast (_β_ = 0.14,

95% CI: 0.09, 0.18) in girls (Table 3). Second, we treated sleep duration as a categorical variable [recommended, shorter, and shortest (reference group)] in mixed-effects models. Compared

to the reference group, children in the shorter and recommended sleep duration groups reported more frequent consumption of healthy snacks [_β_ = 0.48 (95% CI: −0.03, 1.00) and _β_ = 0.78

(95% CI: 0.24, 1.32), respectively] and breakfast [_β_ = 0.38 (95% CI: 0.23, 0.52) and _β_ = 0.38 (95% CI: 0.23, 0.53), respectively]. More significant associations between categories of

sleep duration and healthy snacks and breakfast consumption were found for girls than for boys (Table 3). LONGITUDINAL DATA ANALYSIS: ASSOCIATIONS BETWEEN SLEEP DURATION AND CHILDREN’S

SCREEN TIME First, we treated sleep duration as a continuous variable. Longer sleep duration was associated with less total screen time (_β_ = −0.22, 95% CI: −0.43, −0.02) and less surfing

the internet/using the computer (_β_ = −0.06, 95% CI: −0.09, −0.04) for all children. In sex- stratified analysis, an increase of 1 h/day in sleep duration was associated with a 0.54 h/week

(_β_ = −0.54, 95% CI: −0.80, −0.28) decrease in total screen time, a 0.08 h/day (_β_ = −0.08, 95% CI: −0.11, −0.05) decrease in surfing the internet/using the computer, and a 0.04 h/day

decrease in watching TV (_β_ = −0.04, 95% CI: −0.07, −0.01) for girls. Significant associations were not observed in boys (Table 4). Second, we treated sleep duration as a categorical

variable. A dose–response pattern was observed between sleep duration and child screen time. For all children, compared with the reference group of shortest sleep duration, those with

shorter sleep duration reported less total screen time (_β_ = −1.42, 95% CI: −2.33, −0.50), less time surfing the internet/using the computer (_β_ = −0.24, 95% CI: −0.35, −0.14), and less

time watching TV (_β_ = −0.22, 95% CI: −0.35, −0.08). Furthermore, compared to those with shortest sleep duration, those with recommended sleep duration reported less total screen time (_β_

= −1.70, 95% CI: −2.66, −0.74), less time surfing the internet/using the computer (_β_ = −0.32, 95% CI: −0.43, −0.20), and less time watching TV (_β_ = −0.15, 95% CI: −0.29, −0.01). Similar

findings were observed for girls but not for boys. Compared to girls in the reference group (shortest sleep duration), girls with shorter sleep duration reported less total screen time (_β_

= −2.21, 95% CI: −3.30, −1.11), less time surfing the internet/using the computer (_β_ = −0.22, 95% CI: −0.34, −0.10), and less time watching TV (_β_ = −0.13, 95% CI: −0.24, −0.02). Girls

with recommended sleep duration reported less total screen time (_β_ = −2.80, 95% CI: −3.96, −1.64), less time surfing the internet/using the computer (_β_ = −0.30, 95% CI: −0.44, −0.17),

and less time watching TV (_β_ = −0.12, 95% CI: −0.24, −0.01) (Table 4). LONGITUDINAL DATA ANALYSIS: ASSOCIATIONS BETWEEN SLEEP DURATION AND CHILDREN’S WEIGHT STATUS First, sleep duration

was treated as a continuous variable. Sleep duration was only significantly associated with the risk of central obesity for girls (OR = 0.46, 95% CI: 0.25, 0.85). It was not significantly

associated with BMI or having overweight/obesity in the analyses of all children or by sex (Table 5). Second, sleep duration was treated as a categorical variable. Compared to girls with the

shortest sleep duration (reference group), girls those with shorter sleep duration had lower BMI (_β_ = −0.28, 95% CI: −0.51, −0.05). Also, compared to counterparts in the reference group,

children with recommended sleep duration had significantly reduced risk of general overweight or obesity in all children (OR = 0.70, 95% CI: 0.53, 0.93) and girls (OR = 0.64, 95% CI: 0.43,

0.96). Compared to girls in the shortest sleep duration group, those with shorter sleep duration (OR = 0.19, 95% CI: 0.04, 0.90) had significantly reduced risk of central obesity. This was

not observed for all children or boys (Table 5). The interaction effects between age and sleep duration on eating and drinking behaviors, screen time, and weight status are shown in

Supplemental Tables 1 and 2. We found that age significantly moderated the longitudinal associations of sleep duration with having breakfast (_β_ = 0.02, 95% CI: 0.00, 0.03) and time spent

surfing the internet/using the computer (_β_ = −0.02, 95% CI: −0.03, −0.01). Further age-stratified analyses showed that sleep duration was only significantly associated with having

breakfast (_β_ = 0.09, 95% CI: 0.04, 0.14) and time spent surfing the internet/using the computer (_β_ = −0.09, 95% CI: −0.14, −0.05) among children aged ≥10 years. DISCUSSION Given the

rapid rise in the prevalence of insufficient sleep, overweight and obesity, and related unhealthy lifestyle behaviors in China, especially in its mega-cities, it is of great interest to

examine the characteristics/correlates of sleep and how it may contribute to the epidemic of childhood obesity. Based on large-scale data from a study of five Chinese mega-cities, we

examined sex-specific characteristics and correlates of sleep duration using pooled cross-sectional data and the longitudinal associations of sleep duration with eating and drinking

behaviors, screen time, and weight status in children. Our results demonstrated several important findings. First, we found that children on average slept 8.5 h/day, and the prevalence of

insufficient sleep (the shorter and shortest sleep duration group, combined) was 56.9%. Sex differences in sleep duration or in the prevalence of insufficient sleep were not observed.

Compared with findings reported in Chinese children in 2005 where the mean sleep duration was 9 h and 20 min,4 children from large cities slept approximately 50 min less in 2015 (our study),

and the prevalence of insufficient sleep increased from 28.3 to 56.9% (2015, our study). The prevalence of insufficient sleep found here is similar to rates reported in developed countries.

In a 2015 U.S. study, 57.8% of middle school students reported short sleep duration (<9 h/day for children aged 6–12 years and <8 h/day for teens aged 13–18 years).6 The large

percentages of insufficient sleep among school-aged children demonstrate a global need for promoting sleep health in these still developing populations. Regarding the correlates of sleep

duration, older children and secondary school students reported shorter sleep duration and higher prevalence of insufficient sleep compared to their counterparts. These correlates were

consistent with previous findings in this area.4,6,23 Factors that contribute most to insufficient sleep in older and higher-grade school-aged children include increasing academic demands

and stress, earlier school start times, and more delayed bedtimes.2,24 Few studies have examined associations between places of residence and sleep duration in Chinese children. We found

that, compared to children living in Beijing, children, especially boys, living in Shanghai, Nanjing, Xi’an, and Chengdu reported longer sleep duration. This pattern highlights how unique

regional contexts of economic development and academic stress may serve to differentially impact sleep duration in Chinese children. Previous studies also found the prevalence of

insufficient sleep to be lower in children from middle-economic areas compared to children from high-economic areas.25,26 Another key finding was the observation that children from

≥college-educated parents reported longer sleep duration. These findings corroborate these associations seen in Western settings.27 It may be that more highly educated parents are more aware

of the importance of sleep in their children’s health and development. They may also be more proactive and/or better equipped to deal with child sleep problems. Interestingly,

sex-stratified analyses found boys’ sleep duration to be significantly affected by highest paternal education level and girls’ sleep duration by highest maternal education level. Parents may

be important allies for interventions seeking to increase child sleep duration, and future efforts may benefit from considering sexes of both target children and their parents. Our

longitudinal data analyses revealed that shorter sleep duration reduced the frequency of healthy snacks consumption while increasing the frequency of SSB consumption, breakfast skipping, and

time spent with screens. This was consistent with our hypotheses as well as previous cross-sectional studies28,29,30 of young adults. Several mechanisms have been proposed to explain these

phenomena, including the thought that children sleeping less are awake at irregular times. Also, with shorter sleep duration, children have longer awake times and more time to consume food

and drinks, more energy may be needed to sustain extended wakefulness, and children may experience sleep-related changes in appetite hormones.31,32 Less sleep could also promote tiredness

and fatigue, which could then reduce the motivation to engage in more active behaviors and lead to more sedentary activities, such as television viewing and computer use.33,34 Our findings

demonstrate the potential impacts of insufficient sleep duration on important health behaviors Regarding weight status, however, our longitudinal results only indicated that insufficient

sleep duration increased the risk of central obesity for girls but not general overweight and obesity. This contradicts our hypotheses and the findings of the majority of the extant

literature.35 Differences in findings on associations between sleep duration and obesity could reflect differences in geographical location and cutoff points for sufficient or adequate sleep

duration. For example, a study of sleep duration and obesity in Australian children also found no significant relationships,36 though the non-significant associations may have been

attributable to the low prevalence (7.9%) of the shortest sleep duration in that study. The risk of overweight and obesity may also vary across sleep duration, as the most pronounced

associations have been observed in those reporting ≤4 h sleep per night.37 Additionally, central obesity is a more sensitive indicator of “early health risk” than general obesity.38

Therefore, in children and adolescents, sleep duration may have more observable impacts on central obesity risk than general overweight and obesity risks. By assessing a comprehensive number

of obesity and weight-related behaviors using large-scale 3-year longitudinal data, this study provides critical and novel insights on key causal relationships between sleep duration and

central obesity, eating behaviors, and screen behaviors in children from mega-cities in China. However, this study has a few limitations. First, sleep duration, eating behaviors, and screen

time were child reported. While these data generally correspond well with more objective measures,39,40 the potential for inaccuracies and biases do remain. Future studies could record

bedtimes and wake times to improve sleep duration measurement. Second, we did not assess potential associations of sleep duration with mobile device time and behaviors (e.g., mobile phone

and tablet devices), which are increasingly common. Third, selection bias may have been introduced as this study utilized an open cohort design—some participants graduated or were otherwise

lost to follow-up as new participants were added at each follow-up. Fourth, residual confounding by unmeasured variables is always possible in observational studies. In conclusion,

insufficient sleep was prevalent among children in urban areas in China. Age, school level, city of residence, primary caregiver type, and parental education appear to affect children’s

sleep duration. Short sleep duration may increase the risk of central obesity and unhealthy weight-related behaviors in children, especially girls. Intervention programs and policies should

consider these correlates to increase sleep duration, and such efforts may also help prevent unhealthy weight-related behaviors and childhood obesity. REFERENCES * Paruthi, S. et al.

Recommended amount of sleep for pediatric populations: a consensus statement of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. _J. Clin. Sleep Med._ 12, 785–786 (2016). Article Google Scholar *

Matricciani, L., Olds, T. & Petkov, J. In search of lost sleep: secular trends in the sleep time of school-aged children and adolescents. _Sleep Med. Rev._ 16, 203–211 (2012). Article

Google Scholar * Li, S. et al. Sleep, school performance, and a school-based intervention among school-aged children: a sleep series study in China. _PLoS ONE_ 8, e67928 (2013). Article

CAS Google Scholar * Li, S. et al. Risk factors associated with short sleep duration among Chinese school-aged children. _Sleep Med._ 11, 907–916 (2010). Article Google Scholar *

Gradisar, M., Gardner, G. & Dohnt, H. Recent worldwide sleep patterns and problems during adolescence: a review and meta-analysis of age, region, and sleep. _Sleep Med._ 12, 110–118

(2011). Article Google Scholar * Wheaton, A. G., Jones, S. E., Cooper, A. C. & Croft, J. B. Short sleep duration among middle school and high school students—United States, 2015. _MMWR

Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep._ 67, 85–90 (2018). Article Google Scholar * Moore, M. et al. Correlates of adolescent sleep time and variability in sleep time: the role of individual and health

related characteristics. _Sleep Med._ 12, 239–245 (2011). Article Google Scholar * Chaput, J. P. et al. Systematic review of the relationships between sleep duration and health indicators

in school-aged children and youth. _Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab._ 41, S266–S282 (2016). Article Google Scholar * Gong, Q. H. et al. Associations between sleep duration and physical activity

and dietary behaviors in Chinese adolescents: results from the Youth Behavioral Risk Factor Surveys of 2015. _Sleep Med._ 37, 168–173 (2017). Article Google Scholar * Wang, S., Dong, Y.

H., Wang, Z. H., Zou, Z. & Ma, J. Trends in overweight and obesity among Chinese children of 7-18 years old during 1985-2014. _Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi_ 51, 300–305 (2017). CAS

PubMed Google Scholar * Jia, P., Xue, H., Zhang, J. & Wang, Y. Time trend and demographic and geographic disparities in childhood obesity prevalence in China—evidence from twenty years

of longitudinal data. _Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health_ 14, E369 (2017). Article Google Scholar * Gui, Z. H. et al. Sugar-sweetened beverage consumption and risks of obesity and

hypertension in chinese children and adolescents: a national cross-sectional analysis. _Nutrients_ 9, E1302 (2017). Article Google Scholar * Cao, H. et al. Screen time, physical activity

and mental health among urban adolescents in China. _Prev. Med._ 53, 316–320 (2011). Article Google Scholar * Wu, J. et al. Associations between sleep duration and overweight/obesity:

results from 66,817 Chinese adolescents. _Sci. Rep._ 5, 16686 (2015). Article CAS Google Scholar * Jia, P. et al. School environment and policies, child eating behavior and

overweight/obesity in urban China: the childhood obesity study in China megacities. _Int. J. Obes._ 41, 813 (2017). Article CAS Google Scholar * Li, M. et al. Pocket money, eating

behaviors, and weight status among Chinese children: the Childhood Obesity Study in China mega-cities. _Prev. Med._ 100, 208–215 (2017). Article Google Scholar * National Health Commission

of the People’s Republic of China. Screening for overweight and obesity among school-age children and adolescents. http://www.moh.gov.cn/xxgk/pages/wsbzsearch.jsp2018 (2018). * Meng, L. et

al. Using waist circumference and waist-to-height ratio to access central obesity in children and adolescents. _Chin. J. Evid. Based Pediatr._ 2, 245–252 (2007). Google Scholar * Fu, J. et

al. Childhood sleep duration modifies the polygenic risk for obesity in youth through leptin pathway: the Beijing Child and Adolescent Metabolic Syndrome cohort study. _Int J. Obes.

(Lond.)._ 43, 1556–1567 (2019). Article CAS Google Scholar * Li, L. et al. Sleep duration and cardiometabolic risk among chinese school-aged children: do adipokines play a mediating role?

_Sleep_ 40, zsx042 (2017). PubMed Central Google Scholar * Chen, X., Beydoun, M. A. & Wang, Y. Is sleep duration associated with childhood obesity? A systematic review and

meta‐analysis. _Obesity_ 16, 265–274 (2008). Article Google Scholar * Knutson, K. L. & Lauderdale, D. S. Sleep duration and overweight in adolescents: self-reported sleep hours versus

time diaries. _Pediatrics_ 119, e1056 (2007). Article Google Scholar * Thorleifsdottir, B., Björnsson, J., Benediktsdottir, B., Gislason, T. & Kristbjarnarson, H. Sleep and sleep

habits from childhood to young adulthood over a 10-year period. _J. Psychosom. Res._ 53, 529–537 (2002). Article CAS Google Scholar * Yang, C. K., Kim, J. K., Patel, S. R. & Lee, J.

H. Age-related changes in sleep/wake patterns among Korean teenagers. _Pediatrics_ 115, 250–256 (2005). Article Google Scholar * Song, Y., Zhang, B., Hu, P. & Ma, J. Current situation

of sleeping duration in Chinese Han students in 2010. _Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi_ 48, 596–601 (2014). PubMed Google Scholar * Shi, W., Zhai, Y., Li, W., Shen, C. & Shi, X.

Analysis on sleep duration of 6-12 years old school children in school-day in 8 provinces, China. _Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi_ 36, 450–454 (2015). PubMed Google Scholar * El-Sheikh,

M. et al. Economic adversity and children’s sleep problems: multiple indicators and moderation of effects. _Health Psychol._ 32, 849 (2013). Article Google Scholar * Ogilvie, R. P. et al.

Sleep indices and eating behaviours in young adults: findings from Project EAT. _Public Health Nutr._ 21, 689–701 (2018). Article Google Scholar * Kant, A. K. & Graubard, B. I.

Association of self-reported sleep duration with eating behaviors of American adults: NHANES 2005–2010. _Am. J. Clin. Nutr._ 100, 938–947 (2014). Article CAS Google Scholar * Hale, L.

& Guan, S. Screen time and sleep among school-aged children and adolescents: a systematic literature review. _Sleep Med. Rev._ 21, 50–58 (2015). Article Google Scholar * Dashti, H. S.,

Scheer, F. A., Jacques, P. F., Lamon-Fava, S. & Ordovás, J. M. Short sleep duration and dietary intake: epidemiologic evidence, mechanisms, and health implications. _Adv. Nutr._ 6,

648–659 (2015). Article CAS Google Scholar * Chaput, J. P. et al. Associations between sleep patterns and lifestyle behaviors in children: an international comparison. _Int. J. Obes.

Suppl._ 5, S59 (2015). Article Google Scholar * Must, A. & Parisi, S. Sedentary behavior and sleep: paradoxical effects in association with childhood obesity. _Int. J. Obes._ 33, S82

(2009). Article Google Scholar * Ortega, F. B. et al. Sleep duration and activity levels in Estonian and Swedish children and adolescents. _Eur. J. Appl. Physiol._ 111, 2615–2623 (2011).

Article Google Scholar * Fatima, Y., Doi, S. & Mamun, A. Longitudinal impact of sleep on overweight and obesity in children and adolescents: a systematic review and bias‐adjusted

meta‐analysis. _Obes. Rev._ 16, 137–149 (2015). Article CAS Google Scholar * Hayes, J. F. et al. Sleep patterns and quality are associated with severity of obesity and weight-related

behaviors in adolescents with overweight and obesity. _Child. Obes._ 14, 11–17 (2008). Article Google Scholar * St-Onge, M. P. et al. Sleep duration and quality: impact on lifestyle

behaviors and cardiometabolic health: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. _Circulation_ 134, e367–e386 (2016). Article Google Scholar * Ashwell, M. & Gibson, S.

Waist-to-height ratio as an indicator of ‘early health risk’: simpler and more predictive than using a ‘matrix’based on BMI and waist circumference. _BMJ Open_ 6, e010159 (2016). Article

Google Scholar * Werner, H., Molinari, L., Guyer, C. & Jenni, O. G. Agreement rates between actigraphy, diary, and questionnaire for children’s sleep patterns. _Arch. Pediatrics

Adolesc. Med._ 162, 350–358 (2008). Article Google Scholar * Vandewater, E. A. & Lee, S. J. Measuring children’s media use in the digital age: issues and challenges. _Am. Behav.

Scientist_ 52, 1152–1176 (2009). Article Google Scholar Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We warmly thank all the dedicated and conscientious volunteers (primary and secondary school

students) in the Childhood Obesity Study in China Mega-Cities (COCM). We also thank the COCM research team for data collection and management of the COCM database. This work was supported by

the National Institutes of Health (Grant number U54 HD070725), the United Nations Children’s Fund (Grant number Unicef 2018-Nutrition- 2.1.2.3), and the China Medical Board (Grant number

16-262), a U.S.-based foundation established by John D. Rockefeller in 1914. Funding sources had no role in the design of this study and did not have any role during its execution, analyses,

interpretation of the data, or decision to submit results. AUTHOR INFORMATION Author notes * These authors contributed equally: Lu Ma, Yixin Ding AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Global Health

Institute, School of Public Health, Xi’an Jiaotong University Health Science Center, Xi’an, Shaanxi, China Lu Ma, Yixin Ding & Youfa Wang * Community Health Sciences Division, School of

Public Health, University of California, Berkeley, Berkeley, CA, USA Dorothy T. Chiu * Department of Sociology, Center for Asian & Pacific Economic & Social Development, Research

Institute for Female Culture, Jiangxi University of Finance and Economics, Nanchang, Jiangxi, China Yang Wu * Department of Chronic Non-communicable Diseases, Nanjing Center for Disease

Control and Prevention, Nanjing, Jiangsu, China Zhiyong Wang * Institute of Nutrition and Food Safety Risk Monitoring, Shaanxi Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Xi’an, Shaanxi,

China Xin Wang * Fisher Institute of Health and Well-Being, Department of Nutrition and Health Science, College of Health, Ball State University, Muncie, IN, USA Youfa Wang Authors * Lu Ma

View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Yixin Ding View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar *

Dorothy T. Chiu View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Yang Wu View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google

Scholar * Zhiyong Wang View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Xin Wang View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed

Google Scholar * Youfa Wang View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CONTRIBUTIONS The authors’ responsibilities were as follows—Y. Wang designed

the research and provided essential materials; Y.D. performed statistical analyses; L.M. drafted the manuscript; L.M., D.T.C., and Y. Wang revised the manuscript; Y. Wang and L.M. had

primary responsibility for the final content and are the guarantors; Z.W. and X.W. helped the data collection; all authors critically helped in the interpretation of results, revised the

manuscript, provided relevant intellectual input, and read and approved the final manuscript. CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to Youfa Wang. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS The

authors declare no competing interests. CONSENT STATEMENT Informed consent was obtained from a parent and/or legal guardian for children’s participation in this study. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

PUBLISHER’S NOTE Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION

RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Ma, L., Ding, Y., Chiu, D.T. _et al._ A longitudinal study of sleep, weight status, and weight-related

behaviors: Childhood Obesity Study in China Mega-cities. _Pediatr Res_ 90, 971–979 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-021-01365-1 Download citation * Received: 24 April 2020 * Revised:

23 December 2020 * Accepted: 30 December 2020 * Published: 02 February 2021 * Issue Date: November 2021 * DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-021-01365-1 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share

the following link with will be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer

Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative