Play all audios:

ABSTRACT The glutamate _N_-methyl-d-aspartate receptor antagonist ketamine has a rapid antidepressant effect. Despite large research efforts, ketamine’s mechanism of action in major

depressive disorder (MDD) has still not been determined. In rodents, the antidepressant properties of ketamine were found to be dependent on both the

α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methylisoxazole-4-propionic acid (AMPA) and the serotonin (5-HT)1B receptor. Low 5-HT1B receptor binding in limbic brain regions is a replicated finding in MDD. In

non-human primates, AMPA-dependent increase in 5-HT1B receptor binding in the ventral striatum (VST) has been demonstrated after ketamine infusion. Thirty selective serotonin reuptake

inhibitor-resistant MDD patients were recruited via advertisement and randomized to double-blind monotherapy with 0.5 mg/kg ketamine or placebo infusion. The patients were examined with the

5-HT1B receptor selective radioligand [11C]AZ10419369 and positron emission tomography (PET) before and 24–72 h after treatment. 5-HT1B receptor binding did not significantly alter in

patients treated with ketamine compared with placebo. An increase in 5-HT1B receptor binding with 16.7 % (_p_ = 0.036) was found in the hippocampus after one ketamine treatment. 5-HT1B

receptor binding in VST at baseline correlated with MDD symptom ratings (_r_ = −0.426, _p_ = 0.019) and with reduction of depressive symptoms with ketamine (_r_ = −0.644, _p_ = 0.002). In

conclusion, reduction of depressive symptoms in MDD patients after ketamine treatment is correlated inversely with baseline 5-HT1B receptor binding in VST. Further studies examining the role

of 5-HT1B receptors in the antidepressant mechanism of action of ketamine should be conducted, homing in on the 5-HT1B receptor as an MDD treatment response marker. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING

VIEWED BY OTHERS KETAMINE IN NEUROPSYCHIATRIC DISORDERS: AN UPDATE Article 20 June 2023 IN VIVO SEROTONIN 1A RECEPTOR DISTRIBUTION IN TREATMENT-RESISTANT DEPRESSION Article Open access 03

June 2025 ENHANCED MGLUR5 AVAILABILITY MARKS THE ANTIDEPRESSANT EFFICACY IN MAJOR DEPRESSIVE DISORDER: AN [18F]FPEB PET STUDY Article 18 February 2025 INTRODUCTION Subanesthetic dosing of

ketamine has brought about a paradigm shift in the treatment of major depressive disorder (MDD), with therapeutic effects within hours rather than weeks1. The glutamate hypothesis has so far

dominated the research on the antidepressant properties of ketamine2. The importance of the glutamate _N_-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA)-receptor antagonistic properties for the dissociative

effects of ketamine has been demonstrated3. Diminished antidepressive like response to ketamine has been observed in rodents pretreated with a glutamate

α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methylisoxazole-4-propionic acid (AMPA) receptor antagonist4. However, the mechanism of action of ketamine in MDD treatment is still not determined. Without proper

understanding of the mode of action, we may fail to utilize the rapid antidepressant actions of ketamine in the development of new drugs for MDD. Compounds that could combine the striking

antidepressant effects of ketamine with longer duration of effect, and hopefully without the inherent risk of abuse well known for ketamine, could further revolutionize the field.

Furthermore, there is a lack of markers for ketamine treatment response. Similar to many other effective treatments in psychiatry, ketamine induces a broad spectrum of pharmacodynamic

effects. In addition to NMDA receptor antagonism, it also has affinity for opioid, muscarinic, nicotinic, and serotonin (5-HT)2 receptors5. Most previously characterized antidepressants

increase synaptic serotonin concentrations, either through inhibition of reuptake6 or degradation of serotonin7. The common denominator of serotonergic effect of most antidepressant

treatments may also be shared with ketamine6,8. Dose-dependent increase of serotonin by ketamine in the prefrontal cortex in rodents is indeed a replicated finding in microdialysis

studies9,10. Furthermore, serotonin depletion with 4-chloro-DL-phenylalanine abolished the antidepressive-like effects of S-ketamine in rats. The reduced effect on immobility in the forced

swim test with S-ketamine in serotonin- depleted rats could be restored with administration of a 5-HT1B receptor agonist11. The 5-HT1B receptor is a potential target for antidepressant

treatment based on studies of knockout mice, animal models for depression, MDD case–control studies, antidepressive effects of 5-HT1B receptor ligands, and of the 5-HT1B receptor action of

established treatments for depression12. In the positron emission tomography (PET) studies of in vivo 5-HT1B receptor binding in MDD published so far, low binding in the hippocampus and in

the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) has been reported both in patients with recurrent MDD13 and in patients with MDD and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) comorbidity14. Similarly,

5-HT1B receptor binding was low in the ventral striatum (VST)/ventral pallidum in MDD patients with a family history of depression15. Conversely, a clinically relevant single dose of the

antidepressant escitalopram increased 5-HT1B receptor binding in cortical regions in healthy subjects16. Intriguingly, the only published PET study of ketamine effect on 5-HT1B receptors

demonstrated an AMPA receptor-dependent increase of 5-HT1B receptor binding in the VST, in non-human primates17. VST is a key structure in the reward system, implicated in the anhedonia of

MDD18. 5-HT1B receptor binding is particularly dense in VST in humans19. In line with this, 5-HT1B receptor agonists increase release of the reward behavior regulator dopamine20,21. Ketamine

increases dopamine levels in VST in rodents22. Even though blocking of the MDD treatment effect with a single dose of the opioid receptor antagonist naltrexone has been demonstrated in a

pilot study23, the role of the reward system in the antidepressant mechanism of action of ketamine has not yet been disentangled. The primary aim of this study was to measure the effect of a

subanesthetic dose of ketamine on 5-HT1B receptor binding with PET and the established radioligand [11C]AZ1041936924 in selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) treatment-resistant

patients with MDD. We hypothesized that ketamine would increase 5-HT1B receptor binding in regions with reported low 5-HT1B receptor levels, such as the hippocampus, ACC, and VST. The

secondary aim was to explore correlations between [11C]AZ10419369 binding, MDD symptomatology, and treatment response. PATIENTS AND METHODS SUBJECTS The study was approved by the Regional

Ethical Review Board in Stockholm and by the Radiation safety committee of the Karolinska University Hospital. We strictly adhered to the Helsinki Declaration of 1975 (as revised in 1983).

Patients were recruited through internet-based advertisement directing each patient to a home page with the full information regarding participation in the study. After reading the

information, the patients could volunteer to participate in the study by filling in study-related forms and self-rating scales for depression: Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale

(MADRS-S)25 and Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9)26. Patients fulfilling the study criteria according to self-report were telephone screened by a psychiatrist. Sixty patients were booked

for assessment by a psychiatrist performing a standardized clinical interview including Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.)27 and MADRS-rating, after giving written

informed consent. Out of a total of 832 volunteers 39 met the criteria for participation and were included in the study. The inclusion criteria were as follows: ongoing major depressive

episode according to M.I.N.I., with MADRS ≥ 20, treated for at least 4 weeks with an SSRI in adequate doses without treatment response. The exclusion criteria were as follows: failure to

completely fill out the required forms (_n_ = 192), any circumstance or condition that could reduce the ability to give informed consent (_n_ = 0), not giving informed consent (_n_ = 36),

not being depressed (_n_ = 82), not having received medication for the ongoing depressive episode (_n_ = 56), antidepressant treatment response (_n_ = 35), bipolar disorder (_n_ = 43),

psychosis (_n_ = 8), neurodevelopmental disorders (_n_ = 104), other comorbid disorder as primary diagnoses (_n_ = 22), organic brain disorders (_n_ = 5), cerebral commotion (_n_ = 5),

hypertension (_n_ = 1), obesity or body weight ≥100 kg (_n_ = 47), other significant somatic disorders (_n_ = 4), substance abuse (_n_ = 31), ongoing fluoxetine treatment (_n_ = 25),

contraindications to ketamine treatment, inability to perform magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (_n_ = 22), suicidality (rating > 4 on the last MADRS item or reported serious suicidal

ideation (_n_ = 18)), MADRS < 20 (_n_ = 40), pregnancy (_n_ = 2), and age <20 years or >80 years (_n_ = 12). Three subjects were not included for other reasons. All subjects

provided oral and written informed consent after receiving a complete description of the study and before initiation of any study-related events. The included patients were essentially

healthy apart from their MDD, based on medical history, physical examination, electrocardiography, MRI, and standard lab tests. The included patients had an ongoing depressive episode within

MDD, with one patient being severely depressed (MADRS > 35) and the others suffering from moderate depression. Mean duration of the current depressive episode was 48 months, with a

median duration of 27 months. Twenty of the 39 patients had comorbid conditions according to M.I.N.I. (on average 1.65 comorbid condition per patient in this group) including social phobia

(_n_ = 9), panic disorder (_n_ = 7), agoraphobia (_n_ = 6), generalized anxiety disorder (_n_ = 4), obsessive compulsive disorder (_n_ = 4), antisocial personality disorder (_n_ = 2), and

PTSD (_n_ = 1). Twenty-two of the patients were on antidepressant treatment at the time of inclusion. No patient had responded to the current MDD treatment. Still, the patients were

carefully informed about the risks of withdrawing medications. Ongoing pharmacological treatment was washed out for a time corresponding to at least five half-lives of each drug. Nine of the

initially included patients were excluded, mostly due to withdrawn consent (_n_ = 8). One patient was excluded after testing positive for cocaine and amphetamine in the first drug-screening

test. No patient was discontinued after randomization, although one patient declined ketamine continuation treatment due to unpleasant dissociative side effects of the first ketamine

infusion. Thirty patients fulfilled the study according to protocol. EXAMINATION PROTOCOL After washout of medications, when applicable, patients were examined with a baseline PET (PET1).

Study treatment was given 1–3 days after PET1. A post-treatment PET2 was normally performed the day after study treatment, although examination within 24–72 h after treatment was according

to protocol. For one patient, PET2 was performed the day after a second ketamine infusion, due to radioligand synthesis failure. Patients were assessed by a psychiatrist at the day of PET,

with Clinical Global Impression Scales CGI-S (Severity), CGI-I (Improvement) (at PET2)28, EuroQol (EQ-)5D29, and MADRS30. QIDS-SR31 was completed by the patient at time of PET and just

before first study treatment, and 1, 2, 3, 18, and 24 h after treatment. As side effects of ketamine may entail reduced appetite and disturbed sleep, a shortened version of MADRS omitting

the appetite and sleep items (MADRS-short) was used to assess change in depressive symptoms, as preregistered on Aspredicted.org (#17602). Full MADRS was used for baseline measurements.

Partial treatment response was defined as 25% reduction of MADRS-short scores, with full response reached when MADRS-short was reduced with 50% or more32. STUDY TREATMENT Treatments were

given at Hjärnstimuleringsenheten (a brain stimulation treatment unit), S:t Göran’s hospital, Norra Stockholms psykiatri. The first treatment was randomized, double blind, and

placebo-controlled. Patients were randomized to study treatment with racemic ketamine or saline (2 : 1). Randomization was performed with sealed opaque envelopes, each containing one of the

study treatment allocations. Before the start of treatment, a nurse not involved in patient assessments opened a new envelope, assigning the patient to the randomized treatment allocation.

Active treatment was 0.5 mg/kg racemic ketamine diluted in 100 ml isotonic NaCl solution, given as an intravenous infusion during 40 min. Placebo treatment was an isotonic NaCl solution

only. After treatment, patients were observed for 2 h by trained nurses in a hospital setting. Blood pressure, pulse, wakefulness, hallucinations, and anxiety were assessed at baseline and

every 15 min during the treatment. After PET2, all 30 patients were offered open-label treatment with racemic ketamine until the last clinical examination in the study. The placebo group was

smaller due to the mechanistic focus of the study. Patients and all staff involved in patient assessments and data analysis were blinded to the first study treatment allocation. The week

after PET2, the patients were given ketamine infusions twice a week for a total of four treatments. Depressive symptoms were rated with MADRS by medical staff before and directly after each

treatment. After completion of the study protocol, each patient was offered an appointment to a psychiatrist for initiation of relapse-preventing treatment. POSITRON EMISSION TOMOGRAPHY PET

examinations were performed at the PET center at Karolinska Institutet. During each PET measurement, the subject was placed recumbent with the head in the PET system. Head fixation was

achieved with an individual plaster helmet33. [11C]AZ10419369 was synthesized as previously described24. [11C]AZ10419369 in a sterile physiological phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) solution was

diluted with saline to a volume of 10 ml and then injected as a bolus during 10 s into a cannula inserted into an antecubital vein. The cannula was then immediately flushed with 10 ml

saline. Each patient was examined with PET and the radioligand [11C]AZ10419369 before (PET1) and after the first study treatment (PET2) (mean injected dose at PET1: 358.3 ± 79.9 MBq, mean

injected dose at PET2: 367.5 ± 61.7 MBq). There was no significant difference in injected radioactivity between the first and second PET measurement (_p_ = 0.515). The specific radioactivity

was high (369.3 ± 156.3 GBq/µmol at PET1 and 388.8 ± 136.2 GBq/µmol at PET2, _p_ = 0.475) and the corresponding injected mass of the radioligand was low (0.55 ± 0.44 µg at PET1 and 0.48 ±

0.21 µg at PET2, _p_ = 0.346). The ECAT HRRT (High Resolution Research Tomograph, Siemens Molecular Imaging, TN, USA) PET system was used, with a spatial resolution of ~1.5 mm in the center

and 2.4 mm at 10 cm off-center full-width at half maximum with the current protocol34. Brain radioactivity was measured in a series of consecutive time frames for 95 min. The frame sequence

consisted of 38 frames with nine 10 s frames, two 15 s frames, three 20 s frames, four 30 s frames, four 60 s frames, four 180 s frames, and twelve 360 s frames. MAGNETIC RESONANCE IMAGING

T1-weighted MR images, acquired on a 3T GE MR750 scanner (GE Medical Systems, Milwaukee, WI), were realigned, co-registered with PET images, and segmented into gray matter, white matter, and

cerebrospinal fluid using SPM12 (Wellcome Department of Cognitive Neurology, University College London). Inverted co-registration parameters were obtained to transform ROIs from MR to PET

space. The preselected regions of interest (ROIs) were hippocampus, VST, ACC, and Dorsal BrainStem (DBS). ROIs were defined using Freesurfer (5.0.0, http://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu/),

except for the DBS ROI. The DBS ROI was defined using [11C]AZ10419369 template data in the standard reference space of the Montréal Neurological Institute35 and was transformed into

individual space using FSL (FSL 5.0, Oxford)36. PET IMAGING ANALYSIS Regional binding potential for non-displaceable binding (_BP_ND) was calculated using the simplified reference tissue

model (SRTM37), with the cerebellum as the reference region. The cerebellum ROI was restricted to a smaller region to avoid spill-over from the occipital cortex, cerebrospinal fluid, and

cerebellar vermis as described by Matheson et al.38. A motion correction algorithm39 was applied when subjects showed excessive head movement (see Supplementary Information for further

details). Image analysis was performed blinded to treatment allocation. STATISTICAL ANALYSIS Statistical analyses were performed in R (version 3.6.1, R Development Core Team, 2019).

Differences in regional _BP_NDs when corrected for the effect in the placebo group were tested for significance by calculating the group (ketamine vs. placebo) × time (pre vs. post

intervention) interaction effect in a repeated-measures analysis of variance (RM ANOVA). For exploratory analysis, regional _BP_ND differences within the treatment group were tested using

two-tailed paired _t_-tests. Correlations between regional _BP_NDs and MADRS scores were tested for significance using the Pearson’s correlation method. The _α_-level was set to 0.05.

RESULTS Thirty patients completed the first study treatment and related examination procedures according to protocol (Table 1). One patient chose to decline further study treatments in the

open label phase due to disturbing dissociative side effects. Twenty-nine patients completed study participation including four ketamine treatments with follow up of antidepressant treatment

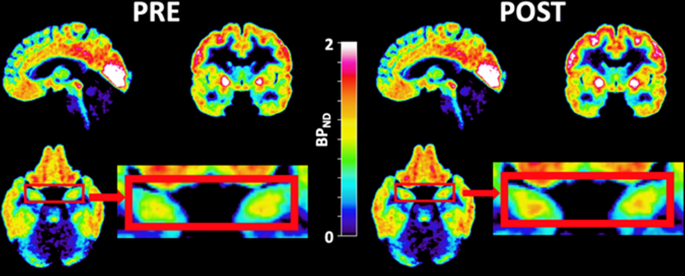

effect. In none of the ROIs, a significant difference in _BP_ND change over time between the ketamine and the placebo group was found, as determined by calculating the group by time

interaction in RM ANOVA. _BP_ND was increased with 16.7% in the hippocampus (Fig. 1 and Table 2, _p_ = 0.036) in response to the first ketamine infusion. There were no significant changes in

_BP_ND after ketamine infusion in any other pre-selected ROI. Placebo treatment did not significantly alter [11C]AZ10419369 _BP_ND in any region (Supplementary Table). There were no

significant differences in total radioactivity, when adjusted for injected dose, in the reference region between PET examinations for the ketamine group (_p_ = 0.800), the placebo group (_p_

= 0.131), or in changes between groups (_p_ = 0.390). Post-treatment MADRS was significantly lower after active treatment with ketamine compared to placebo (adjusted _p_ = 0.019), with

MADRS scores decreasing from 26.3 ± 6.58 to 16.00 ± 7.28 after the first ketamine treatment (adjusted _p_ < 0.001) compared with that from 30.8 ± 4.92 to 25.00 ± 9.24 with placebo

(adjusted _p_ = 0.455). After the first treatment, partial response was achieved by 75% treated with ketamine vs. 30% in the placebo group (_p_ = 0.045), and 35% of the ketamine-treated

patients and 20% of the patients given placebo fulfilled the criterion for response (_p_ = 0.675). After four ketamine treatments 84% of the patients initially given ketamine and 90% of the

initial placebo group displayed partial ketamine treatment response (_p_ = 1) and 74 vs. 70% responded to the ketamine treatment series (_p_ = 1). Altogether 72% of the patients in the study

responded to the full ketamine treatment, while remission was obtained for 48% of the patients. Patients who received active treatment in the double blinded phase were all convinced that

they received ketamine, while four out of ten placebo treated patients thought that they actually were given active treatment. Ketamine treated patients also improved according to QIDS-SR 24

h post infusion (from 17.5 ± 4.1 to 10.9 ± 5.3, _p_ < 0.001), and displayed improvements in EQ-5D subjective state of health (from 37.5 ± 17.8 to 57.4 ± 21.0, _p_ < 0.001). There were

no significant improvements in these self-ratings after placebo treatment. Ketamine-treated patients also displayed improved clinical global impression (CGI-S pretreatment: 4.11 ± 0.48,

post treatment: 3.06 ± 1.09, _p_ = 0.001; average CGI-I: 2.33) as measured at time of PET. The antidepressant effect of ketamine treatment was rapid, with a significant decrease of QIDS-SR

after 1 h (from 17.9 ± 4.1 to 15.3 ± 4.3, adjusted _p_ = 0.04) and larger QIDS-SR reduction with ketamine than placebo 18 h after start of infusion (adjusted _p_ = 0.01). At baseline, _BP_ND

in the VST correlated inversely with MADRS (_r_ = −0.426, _p_ = 0.019), which was not the case in any other selected brain region. In addition, there was an inverse correlation between

baseline _BP_ND in VST and change in MADRS-short scores after first study treatment in the ketamine group (_r_ = −0.644, _p_ = 0.002, Fig. 2). Furthermore, [11C]AZ10419369 _BP_ND at baseline

in the DBS correlated negatively with change in MADRS-short with ketamine (_r_ = −0.510, _p_ = 0.022). There were no correlations between baseline _BP_ND and changes in MADRS-short in the

placebo group. Changes in _BP_ND with treatment did not correlate with antidepressant effect as measured with MADRS. DISCUSSION In this randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind PET

study, 5-HT1B receptor binding was studied in SSRI resistant MDD patients, before and 24–72 h after ketamine infusion, a time interval chosen for peak antidepressant effect. No significant

differences were found in overall [11C]AZ10419369 _BP_ND changes pre and post treatment between patients receiving ketamine infusion and the placebo group. In the exploratory analysis, a

significant increase in [11C]AZ10419369 _BP_ND was found in the hippocampus in patients receiving ketamine treatment. There were no other significant changes in radioligand binding in the

preregistered ROIs. It is not clear why we could not replicate the increased 5-HT1B receptor binding in VST in non-human primates after ketamine infusion17. A number of explanations are

possible. First, in contrast with the study by Yamanaka et al.17, we settled for disentangling the 5-HT1B receptor effect of ketamine by comparing it with placebo treatment, which reduced

depressive symptoms in some of the patients. Second, there may be species differences and differences in subject states, where we examined SSRI treatment-resistant MDD patients rather than

healthy apes. Third, and perhaps most important, ketamine doses in our study was subanesthetic, whereas in the previous primate 5-HT1B receptor PET study the administered doses were

anesthetic17. The hippocampus is a key region in the neurocircuitry of MDD40,41. A number of studies have demonstrated ketamine’s effects on hippocampal neurons in rodents42. AMPA receptor

antagonist pretreatment has blocked ketamine’s reduction of immobility in the forced swim test, while reversing the attenuation of phosphorylation of GluR1 AMPA receptors in the hippocampus

induced by ketamine4. Optogenetic inactivation of the ventral hippocampus–medial prefrontal cortex pathway has been shown to reverse ketamine’s effect on immobility in the forced swim

test43. In humans, low 5-HT1B receptor binding in the hippocampus in MDD patients has been reported in previous studies13,14. In ketamine-treated patients, [11C]AZ10419369 _BP_ND in the

hippocampus increased significantly after treatment. The increase in hippocampal [11C]AZ10419369 _BP_ND after ketamine may reflect both increased 5-HT1B receptor density and reduced

serotonin concentration, as displacement of [11C]AZ10419369 binding has been demonstrated after pharmacological challenges expected to increase serotonin levels at least twofold16,44.

However, with a single dose of 20 mg escitalopram given to healthy human volunteers, there was no radioligand displacement. Furthermore, [11C]AZ10419369 _BP_ND has not been shown to

correlate with concentrations of serotonin and its metabolite 5-HIAA (5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid) in cerebrospinal fluid45. Thus, although a change in serotonin concentration cannot be ruled

out, the increase in hippocampal _BP_ND most likely reflects increased 5-HT1B receptor density after ketamine for MDD. Increased 5-HT1B receptor density with ketamine treatment would be in

line with the low 5-HT1B receptor binding previously shown in MDD and with the rescue of the antidepressive properties of ketamine by 5-HT1B receptor agonism after serotonin depletion11. In

our study, there was a distinct negative correlation between baseline 5-HT1B receptor _BP_ND in the VST and change in MADRS-short associated with ketamine treatment, with larger treatment

effects in patients having lower pretreatment 5-HT1B receptor levels. Furthermore, baseline 5-HT1B receptor _BP_ND in the VST correlated inversely with pretreatment MADRS scores. This is in

line with the low ventral striatal 5-HT1B receptor _BP_ND previously described in MDD patients15. As 5-HT1B receptor stimulation increases dopamine release, low 5-HT1B receptor binding would

in theory result in low dopamine levels in VST. VST is a core structure in the reward system and dopamine a major mediator of reward related behavior. Impaired reward reversal learning has

indeed been demonstrated in MDD patients, along with reduced striatal activity during unexpected rewards and dopamine dysregulation46,47. Ketamine increases dopamine levels in the VST in

rodents, even though ketamine-induced dopamine release appears less pronounced in humans22. Our results corroborate the 5-HT1B receptor as a biomarker for the depressive state and puts

forward 5-HT1B receptor binding as a ketamine treatment response marker. Even in a well-designed, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, PET study, there are a number of limitations.

First, even though this is the largest PET study of ketamine neuroreceptor effects in MDD so far, the sample size is still a limitation, with inherent risk of type II errors, making the

nonsignificant differences in 5-HT1B receptor binding in the ketamine group vs. placebo inconclusive. Considering the effect in 5-HT1B receptor binding in the hippocampus seen in our data, a

sample size of 110 subjects would be required to detect significant differences between treatment groups with a power of 70%. Second, with the dissociative effects of ketamine, blinding

becomes a challenge. The ketamine-treated patients all realized that they received active treatment. However, a surprisingly large part of the placebo-treated patients thought that they had

received ketamine as well. This suggest the numerical pre-post differences between ketamine and placebo are most likely not to be driven by unblinding. Third, we studied SSRI

treatment-resistant patients. This group may well respond differently to ketamine with regards to the addressed serotonin target the 5-HT1B receptor than non-resistant patients. Thus, we

cannot know whether the association between antidepressant effects of ketamine and 5-HT1B receptor binding in the hippocampus can be generalized to the MDD population as a whole. Fourth, the

DBS is a region with low signal-to-noise ratio and suboptimal test–retest properties for [11C]AZ10419369 in this region with SRTM, the standard reference tissue model for this

radioligand48. Hence, we also applied wavelet filters (wavelet aided parametric imaging) for DBS data (see supplemental section for further details), but could still not detect any

significant changes in 5-HT1B receptor _BP_ND after ketamine infusion (_p_ = 0.27). In conclusion, we found that in patients with SSRI-resistant MDD, reduction of depressive symptoms after

ketamine treatment correlated inversely with 5-HT1B receptor binding in the VST at baseline. Even though we found no statistically significant differences in overall 5-HT1B receptor binding

changes between ketamin-treated patients and the placebo group, there was an increased 5-HT1B receptor binding in the hippocampus after ketamine treatment. With this study, we suggest a role

for the 5-HT1B receptor in the antidepressant mechanism of action of ketamine and we encourage further research that examines 5-HT1B receptor binding and related measurements as response

markers for ketamine treatment effect in MDD. REFERENCES * Berman, R. M. et al. Antidepressant effects of ketamine in depressed patients. _Biol. Psychiatry_ 47, 351–354 (2000). Article CAS

PubMed Google Scholar * Maeng, S. & Zarate, C. A. Jr. The role of glutamate in mood disorders: results from the ketamine in major depression study and the presumed cellular mechanism

underlying its antidepressant effects. _Curr. Psychiatry Rep._ 9, 467–474 (2007). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Gunduz-Bruce, H. The acute effects of NMDA antagonism: from the rodent

to the human brain. _Brain Res. Rev._ 60, 279–286 (2009). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Maeng, S. et al. Cellular mechanisms underlying the antidepressant effects of ketamine: role

of alpha-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methylisoxazole-4-propionic acid receptors. _Biol. Psychiatry_ 63, 349–352 (2008). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Tyler, M. W., Yourish, H. B., Ionescu,

D. F. & Haggarty, S. J. Classics in chemical neuroscience: ketamine. _ACS Chem. Neurosci._ 8, 1122–1134 (2017). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Lundberg, J., Tiger, M., Landen,

M., Halldin, C. & Farde, L. Serotonin transporter occupancy with TCAs and SSRIs: a PET study in patients with major depressive disorder. _Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol._ 15, 1167–1172

(2012). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Shulman, K. I., Herrmann, N. & Walker, S. E. Current place of monoamine oxidase inhibitors in the treatment of depression. _CNS Drugs_ 27,

789–797 (2013). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * du Jardin, K. G. et al. Potential involvement of serotonergic signaling in ketamine’s antidepressant actions: a critical review.

_Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry_ 71, 27–38 (2016). Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Ago, Y. et al. R)-Ketamine induces a greater increase in prefrontal 5-HT release than

(S)-ketamine and ketamine metabolites via an AMPA receptor-independent mechanism. _Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol_. 22, 665–674 (2019). * Lopez-Gil, X. et al. Role of serotonin and

noradrenaline in the rapid antidepressant action of ketamine. _ACS Chem. Neurosci._ 10, 3318–3326 (2019). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * du Jardin, K. G. et al. S-ketamine mediates

its acute and sustained antidepressant-like activity through a 5-HT1B receptor dependent mechanism in a genetic rat model of depression. _Front. Pharm._ 8, 978 (2017). Article CAS Google

Scholar * Tiger, M., Varnas, K., Okubo, Y. & Lundberg, J. The 5-HT1B receptor - a potential target for antidepressant treatment. _Psychopharmacology (Berl.)_ 235, 1317–1334 (2018).

Article CAS Google Scholar * Tiger, M. et al. Low serotonin1B receptor binding potential in the anterior cingulate cortex in drug-free patients with recurrent major depressive disorder.

_Psychiatry Res._ 253, 36–42 (2016). Article Google Scholar * Murrough, J. W. et al. The effect of early trauma exposure on serotonin type 1B receptor expression revealed by reduced

selective radioligand binding. _Arch. Gen. Psychiatry_ 68, 892–900 (2011). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Murrough, J. W. et al. Reduced ventral striatal/ventral pallidal

serotonin1B receptor binding potential in major depressive disorder. _Psychopharmacology (Berl.)_ 213, 547–553 (2011). Article CAS Google Scholar * Nord, M., Finnema, S. J., Halldin, C.

& Farde, L. Effect of a single dose of escitalopram on serotonin concentration in the non-human and human primate brain. _Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol._ 16, 1577–1586 (2013). Article

CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Yamanaka, H. et al. A possible mechanism of the nucleus accumbens and ventral pallidum 5-HT1B receptors underlying the antidepressant action of ketamine: a PET

study with macaques. _Transl. Psychiatry_ 4, e342 (2014). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Knowland, D. & Lim, B. K. Circuit-based frameworks of depressive

behaviors: The role of reward circuitry and beyond. _Pharm. Biochem. Behav._ 174, 42–52 (2018). Article CAS Google Scholar * Varnas, K., Hall, H., Bonaventure, P. & Sedvall, G.

Autoradiographic mapping of 5-HT(1B) and 5-HT(1D) receptors in the post mortem human brain using [(3)H]GR 125743. _Brain Res._ 915, 47–57 (2001). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar *

Alex, K. D. & Pehek, E. A. Pharmacologic mechanisms of serotonergic regulation of dopamine neurotransmission. _Pharm. Ther._ 113, 296–320 (2007). Article CAS Google Scholar * Li, N.

& Jasanoff, A. Local and global consequences of reward-evoked striatal dopamine release. _Nature_ 580, 239–244 (2020). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Kokkinou,

M., Ashok, A. H. & Howes, O. D. The effects of ketamine on dopaminergic function: meta-analysis and review of the implications for neuropsychiatric disorders. _Mol. Psychiatry_ 23, 59–69

(2018). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Williams, N. R. et al. Attenuation of antidepressant effects of ketamine by opioid receptor antagonism. _Am. J. Psychiatry_ 175, 1205–1215

(2018). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Varnas, K. et al. Quantitative analysis of [11C]AZ10419369 binding to 5-HT1B receptors in human brain. _J. Cereb. Blood Flow.

Metab._ 31, 113–123 (2011). Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Svanborg, P. & Asberg, M. A comparison between the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) and the self-rating version of the

Montgomery Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS). _J. Affect Disord._ 64, 203–216 (2001). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L. & Williams, J. B. The

PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. _J. Gen. Intern. Med._ 16, 606–613 (2001). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Sheehan, D. V. et al. The

Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. _J. Clin. Psychiatry_

59(Suppl 20), 22–33 (1998). quiz 34-57. PubMed Google Scholar * Guy, W. _ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology_ (U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, Rockville,

1976). Google Scholar * EuroQol, G. EuroQol-a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. _Health Policy_ 16, 199–208 (1990). Article Google Scholar * Montgomery,

S. A. & Asberg, M. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. _Br. J. Psychiatry_ 134, 382–389 (1979). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Rush, A. J. et al. The

16-Item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (QIDS), clinician rating (QIDS-C), and self-report (QIDS-SR): a psychometric evaluation in patients with chronic major depression. _Biol.

Psychiatry_ 54, 573–583 (2003). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Rush, A. J. et al. Report by the ACNP Task Force on response and remission in major depressive disorder.

_Neuropsychopharmacology_ 31, 1841–1853 (2006). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Bergstrom, M. et al. Head fixation device for reproducible position alignment in transmission CT and

positron emission tomography. _J. Comput. Assist. Tomogr._ 5, 136–141 (1981). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Varrone, A. et al. Advancement in PET quantification using 3D-OP-OSEM

point spread function reconstruction with the HRRT. _Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging_ 36, 1639–1650 (2009). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Evans, A. et al. 3D Statistical Neuroanatomical

Models from 305 MRI Volumes. In _IEEE-Nuclear S. Symposium, and Medical Imaging Conference_ 1813–1817 (IEEE, San Francisco, CA, USA, 1993). * Jenkinson, M., Beckmann, C. F., Behrens, T. E.,

Woolrich, M. W. & Smith, S. M. Fsl. _Neuroimage_ 62, 782–790 (2012). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Lammertsma, A. A. & Hume, S. P. Simplified reference tissue model for PET

receptor studies. _Neuroimage_ 4, 153–158 (1996). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Matheson, G. J. et al. Reliability of volumetric and surface-based normalisation and smoothing

techniques for PET analysis of the cortex: a test-retest analysis using [(11)C]SCH-23390. _Neuroimage_ 155, 344–353 (2017). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Mead, N. A. A simplex

method for function mimimization. _Comput. J._ 7, 308–313 (1965). Article Google Scholar * Malykhin, N. V. & Coupland, N. J. Hippocampal neuroplasticity in major depressive disorder.

_Neuroscience_ 309, 200–213 (2015). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Mayberg, H. S. Limbic-cortical dysregulation: a proposed model of depression. _J. Neuropsychiatry Clin. Neurosci._

9, 471–481 (1997). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Duman, R. S., Sanacora, G. & Krystal, J. H. Altered connectivity in depression: GABA and glutamate neurotransmitter deficits

and reversal by novel treatments. _Neuron_ 102, 75–90 (2019). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Carreno, F. R. et al. Activation of a ventral hippocampus-medial

prefrontal cortex pathway is both necessary and sufficient for an antidepressant response to ketamine. _Mol. Psychiatry_ 21, 1298–1308 (2016). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar *

Finnema, S. J., Varrone, A., Hwang, T. J., Halldin, C. & Farde, L. Confirmation of fenfluramine effect on 5-HT(1B) receptor binding of [(11)C]AZ10419369 using an equilibrium approach.

_J. Cereb. Blood Flow. Metab._ 32, 685–695 (2012). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Tiger, M. et al. No correlation between serotonin and its metabolite 5-HIAA in the cerebrospinal

fluid and [(11) C]AZ10419369 binding measured with PET in healthy volunteers. _Synapse_ 68, 480–483 (2014). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Robinson, O. J., Cools, R., Carlisi, C.

O., Sahakian, B. J. & Drevets, W. C. Ventral striatum response during reward and punishment reversal learning in unmedicated major depressive disorder. _Am. J. Psychiatry_ 169, 152–159

(2012). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Tiger, M. et al. [(11) C]raclopride positron emission tomography study of dopamine-D2/3 receptor binding in patients with severe

major depressive episodes before and after electroconvulsive therapy and compared to control subjects. _Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci._ 74, 263–269 (2020). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

* Nord, M., Finnema, S. J., Schain, M., Halldin, C. & Farde, L. Test-retest reliability of [(11)C]AZ10419369 binding to 5-HT 1B receptors in human brain. _Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol.

Imaging_ 41, 301–307 (2014). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This study was funded by the Swedish Research Council 2013-09304, The Söderström König

Foundation SLS-746501 (support for Mikael Tiger), Centre for Psychiatry Research, Region Stockholm and Karolinska Institutet (Mikael Tiger), Region Stockholm (ALF project 20170192, Johan

Lundberg), and Johan Lundberg was supported by Region Stockholm (higher clinical research appointment). Emma Veldman was supported by Psykiatrifonden. Lars Farde is greatly acknowledged for

discussions on study design; Andrea Varrone for providing PET slots and Opokua Cavaco-Britton for steadily supporting the patients through the PET examinations; Per Stenkrona, Jonas

Svensson, and Max Andersson for assisting with the PET experiments; Göran Rosenqvist for help with the web-based pre-screening tool; radiochemist Johan Ulin for radioligand synthesis; the

nurses at Hjärnstimuleringsenheten for randomization and dosing; Mats Persson, Ullvi Båve, and Karin Beckman for assisting in screening of patients; Haitang Jiang for assistance with

clinical data statistics; and Hampus Yngwe for assisting with organizing clinical data. AUTHOR INFORMATION AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Centre for Psychiatry Research, Department of Clinical

Neuroscience, Karolinska Institutet and Stockholm Health Care Services, Region Stockholm, Sweden Mikael Tiger, Emma R. Veldman, Carl-Johan Ekman, Christer Halldin & Johan Lundberg *

Department of Clinical Neuroscience, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden Per Svenningsson Authors * Mikael Tiger View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed

Google Scholar * Emma R. Veldman View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Carl-Johan Ekman View author publications You can also search for this

author inPubMed Google Scholar * Christer Halldin View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Per Svenningsson View author publications You can

also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Johan Lundberg View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence

to Mikael Tiger. ETHICS DECLARATIONS CONFLICT OF INTEREST The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION PUBLISHER’S NOTE Springer Nature remains neutral

with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION SUPPLEMENTARY TABLE RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS OPEN

ACCESS This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format,

as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third

party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the

article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright

holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Tiger, M., Veldman, E.R., Ekman, CJ.

_et al._ A randomized placebo-controlled PET study of ketamine´s effect on serotonin1B receptor binding in patients with SSRI-resistant depression. _Transl Psychiatry_ 10, 159 (2020).

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-020-0844-4 Download citation * Received: 16 April 2020 * Revised: 26 April 2020 * Accepted: 01 May 2020 * Published: 01 June 2020 * DOI:

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-020-0844-4 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not

currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative