Play all audios:

ABSTRACT Self-amplifying RNA (saRNA) is a promising biotherapeutic tool that has been used as a vaccine against both infectious diseases and cancer. saRNA has been shown to induce protein

expression for up to 60 days and elicit immune responses with lower dosing than messenger RNA (mRNA). Because saRNA is a large (~9500 nt), negatively charged molecule, it requires a delivery

vehicle for efficient cellular uptake and degradation protection. Lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) have been widely used for RNA formulations, where the prevailing paradigm is to encapsulate RNA

within the particle, including the first FDA-approved small-interfering siRNA therapy. Here, we compared LNP formulations with cationic and ionizable lipids with saRNA either on the interior

or exterior of the particle. We show that LNPs formulated with cationic lipids protect saRNA from RNAse degradation, even when it is adsorbed to the surface. Furthermore, cationic LNPs

deliver saRNA equivalently to particles formulated with saRNA encapsulated in an ionizable lipid particle, both in vitro and in vivo. Finally, we show that cationic and ionizable LNP

formulations induce equivalent antibodies against HIV-1 Env gp140 as a model antigen. These studies establish formulating saRNA on the surface of cationic LNPs as an alternative to the

paradigm of encapsulating RNA. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS AMINE HEADGROUPS IN IONIZABLE LIPIDS DRIVE IMMUNE RESPONSES TO LIPID NANOPARTICLES BY BINDING TO THE RECEPTORS TLR4 AND

CD1D Article 03 October 2024 LIQUID CRYSTALLINE INVERTED LIPID PHASES ENCAPSULATING SIRNA ENHANCE LIPID NANOPARTICLE MEDIATED TRANSFECTION Article Open access 12 February 2024 A CAREFUL LOOK

AT LIPID NANOPARTICLE CHARACTERIZATION: ANALYSIS OF BENCHMARK FORMULATIONS FOR ENCAPSULATION OF RNA CARGO SIZE GRADIENT Article Open access 29 January 2024 INTRODUCTION Biotherapeutics

based on messenger RNA (mRNA) are a promising strategy for both vaccines and protein replacement therapy. To date, mRNA has been used preclinically for a variety of vaccine indications,

including infectious diseases such as influenza [1, 2], rabies virus [3], RSV [4], HIV-1 [5, 6], HCV [7], Zika virus [8], and Ebola virus [9], as well as for cancer vaccines, including lung

cancer [10], prostate cancer [11], pancreatic cancer [12], and melanoma [13]. Furthermore, a number of mRNA vaccines against both infectious disease and cancer indications are currently

being tested in various human clinical vaccine trials at different stages [14]. Self-amplifying mRNA (saRNA) is an alternative approach to mRNA vaccines, and has been shown to induce immune

responses with lower doses of saRNA than mRNA (10- to 100-fold lower) [15], and results in prolonged protein expression for up to 60 days in vivo [4]. Upon delivery into the cytoplasm, an

saRNA is translated to produce four nonstructural proteins that make up the replicase, which is able to make multiple identical copies of the original strand of RNA, resulting in

exponentially more copies of RNA [16]. Whether mRNA (2000–5000 nt) or saRNA (8000–10,000 nt) is used for gene delivery, it is necessary to pair it with a delivery platform in order to

enhance cellular uptake. mRNA has been previously formulated using a range of cationic delivery platforms, wherein the overarching principle is to use a cationic/ionizable lipid or polymer

to electrostatically complex the anionic RNA molecules, reducing the size of the particle and facilitating cellular uptake. Approaches have explored the use of polyplexes [11, 17], emulsions

[5, 18], and lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) [19, 20]. Currently, the only FDA-approved RNA-based therapy is patisiran, a small-interfering RNA (siRNA)-based therapy for the treatment of hATTR

amyloidosis, which is formulated in liposomes prepared using an ionizable lipid [21]. In order to enhance mRNA delivery efficiency, extensive optimization of LNP formulations has been

performed, including in vivo design of experiment approaches, which have been shown to enhance the mRNA efficacy just by optimizing the formulation components. However, these specific

formulations do not necessarily enhance the efficacy of other types of RNA, such as siRNA [22]. Previous studies with LNP formulations have shown that encapsulating RNA within the particle

protects the RNA from degradation by RNAse compared with naked RNA [4]. However, to our knowledge, previous studies have not explored whether RNA needs to be encapsulated within the LNP in

order to protect it, or whether complexation to the surface of the particle is sufficient for protection and/or delivery. Logically, cationic LNPs should be able to complex RNA in a similar

manner to polyplexes, which have been shown to protect RNA from degradation by complexation and condensation, despite the RNA being exposed on the surface of the complex [17, 23]. Thus, we

postulated that LNPs could be used to complex RNA in a similar manner to polyplexes by first forming the LNP and then electrostatically adsorbing the RNA to the surface of the particle. We

further hypothesized that LNP formulations could be tailored and optimized to complex RNA by varying the properties of the complexing lipid. Here, we systematically compare LNPs with saRNA

on the interior versus exterior of the particle. We chose three complexing lipids based on their properties and previous use in mRNA formulations, including C12-200, an ionizable lipidoid

previously used for siRNA and mRNA delivery [22, 24], dimethyldioctadecylammonium (DDA), a cationic lipid previously used in liposomal adjuvant formulations [25], and

1,2-dioleoyl-3-trimethylammonium propane (DOTAP), a cationic lipid previously used in mRNA LNP and emulsion formulations [5, 26]. We incorporated each lipid into LNP formulations based on

previously used combinations of the complexing lipid, cholesterol, and a phospholipid [22], with saRNA either on the interior or exterior of the particle. We evaluated the in vitro

transfection efficiency of each of the formulations, using firefly luciferase (fLuc) as a reporter protein and characterized how well each of the formulations protects saRNA from degradation

by RNAse. Furthermore, we quantified the in vivo luciferase expression of each saRNA interior/exterior LNP formulations. Finally, we determined the immunogenicity of LNP formulations using

an saRNA expressing HIV-1 Env gp140 as a model antigen. MATERIALS AND METHODS SARNA SYNTHESIS saRNA encoding the nonstructural proteins of the Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus (VEEV) and

either fLuc [27] or HIV-1 Env gp140 [28] was synthesized using in vitro transcription. Plasmid DNA (pDNA) was transformed into _Escherichia coli_ and cultured in 50 mL of LB with 100 μg/mL

carbenicillin (Sigma Aldrich, UK), and purified using a Plasmid Plus MaxiPrep kit (QIAGEN, UK). pDNA concentration and purity were measured on a NanoDrop One (Thermo Fisher, UK), and then

linearized using MluI for 3 h at 37 °C, followed by heat inactivation at 80 °C for 20 min. Uncapped in vitro RNA transcripts were synthesized using 1 μg of linearized DNA template in a

MEGAScript reaction (Promega, UK), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Transcripts were then purified by overnight LiCl precipitation at −20 °C, pelleted by centrifugation at 14,000×

RPM and 4 °C for 20 min, washed 1× with 70% EtOH, centrifuged at 14,000× RPM and 4 °C for 5 min, and then resuspended in UltraPure H2O. Purified transcripts were then capped by

simultaneously using the ScriptCap™ m7G Capping System (CellScript, Madison, WI, USA) and ScriptCap™ 2′-O-Methyltransferase Kit (CellScript, Madison, WI, USA), according to the

manufacturer’s protocol. Capped transcripts were then purified again by LiCl precipitation and stored at −80 °C. PRODUCTION OF LNPS WITH ENCAPSULATED SARNA DDA bromide (Sigma, UK) and DOTAP

(Avanti Polar Lipids, AL, USA) were used as received. C12-200 was synthesized by reacting 1 M equivalent of N1-(2-(4-(2-aminoethyl)piperazin-1-yl)ethyl)ethane-1,2-diamine (Enamine Ltd.,

Kyiv, Ukraine) with 7 M equivalents of 1,2-epoxydodecane (Sigma) at 80 °C for 2.5 days, according to published protocols [29]. LNPs with encapsulated saRNA (Fig. 1) were prepared on a

μEncapsulator 1 System (Dolomite Bio, Royston, UK). The lipid solution was prepared by dissolving lipids in 90% EtOH at a total concentration of 1.5 mg/mL consisting of 35 mol% complexing

lipid (C12-200, DDA, or DOTAP), 49 mol% cholesterol (Sigma), and 16 mol% 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (Avanti Polar Lipids). A volume of 100 μL of the lipid solution was

loaded into one side of the μEncapsulator reservoir, while the other side was loaded with 100 μL of saRNA in citrate buffer (pH = 3), and the same solutions were loaded into the

corresponding pumps. The ratio of complexing lipid to RNA was maintained at a N/P ratio of 12:1. A 50μm fluorophilic chip with a T-junction and subsequent phosphate buffer saline (PBS)

(Sigma Aldrich, UK) dilution channel was used. LNPs were prepared using the following conditions: chip T = 70 °C, lipid solution pump pressure = 2000 Pa, citrate buffer pump pressure = 666

Pa, and PBS pump pressure = 2000 Pa. LNPs were purified by dialyzing against PBS in a 3500 MWCO dialysis cartridge (Thermo Fisher, UK) for 4 h. PRODUCTION OF LNPS WITH EXTERIORLY COMPLEXED

SARNA LNPs with saRNA complexed to the exterior of the particle (Fig. 1) were prepared similarly to LNPs with encapsulated saRNA. However, instead of loading citrate buffer with saRNA into

the reservoir, naive citrate buffer was loaded, and the instrument was run at identical conditions, until 5 mL of LNPs were produced. The LNPs were then purified by dialysis as stated above.

For the final formulation, saRNA in citrate buffer (pH 3) was added at an N/P ratio of 12:1 and subsequently diluted in pH 7 PBS to the proper concentration 30–45 min prior to the start of

the experiment. Exteriorly complexed LNPs were not further purified. QUANTIFICATION OF ENCAPSULATION EFFICIENCY The saRNA loading in LNP formulations was quantified using a Quant-iT

RiboGreen assay (Thermo Fisher, UK) as previously described [4]. Samples were diluted tenfold in 1× TE buffer containing 0.5% (v/v) Triton X-100 (Sigma Aldrich, UK). Standard solutions were

also prepared in 1× TE containing 0.5% (v/v) Triton X-100 to account for any variation in fluorescence. The assay was performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Samples were loaded

on a black, 96-well plate, and analyzed for fluorescence on a microplate reader (BMG LABTECH, UK) at an excitation of 485 nm and emission at 528 nm. In vitro and in vivo dosing was defined

based on the calculated encapsulated dose. LNP CHARACTERIZATION The size and surface charge of LNPs were assessed with saRNA on either the interior or exterior of the particle. A volume of

100 μL of LNPs were diluted into 900 μL of PBS and equilibrated at room temperature (RT) (20 °C), prior to analysis. The particle size and polydispersity index (PDI) were characterized using

a Zetasizer Nano ZS (Malvern Instruments, UK) with Zetasizer 7.1 software (Malvern, UK), using 850 μL of diluted particles in a 1-mL cuvette and the following settings: material refractive

index of 1.4, absorbance of 0.01, dispersant viscosity of 0.882 cP, refractive index of 1.33, and dielectric constant of 79. Each sample was analyzed for up to 100 runs, or until measurement

was suitably stabilized. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was performed on LNP formulations that were dialyzed against H2O overnight, stained with 2% uranyl acetate, and imaged on a

TEM-2100 Plus Electron Microscopy (JEOL, Peabody, MA, USA) using a voltage of 80 kV. IN VITRO TRANSFECTIONS Transfections were performed in HEK293T.17 cells (ATCC, USA) that were maintained

in complete Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (cDMEM) (Gibco, Thermo Fisher, UK) containing 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), 5 mg/mL l-glutamine, and 5 mg/mL penicillin/streptomycin (Thermo

Fisher, UK). Cells were confirmed to be mycoplasma free prior to experimentation and were plated at a density of 50,000 cells per well in a clear 96-well plate, 48 h prior to transfection. A

dose of 100 ng of interior or exterior complexed saRNA encoding fLuc was used per well in a volume of 100 μL of PBS, which was added to a well already containing 50 μL of transfection

medium (DMEM with 5 mg/mL l-glutamine). For the “FCS” transfection condition, 50% (v/v) FCS was added to the transfection media immediately after formulation addition. For the “RNAse”

condition, 3.8 milliarbitrary units (mAU) of RNAse (Life Technologies) per μg of RNA was added directly to the transfection media immediately after formulation addition. Cells were allowed

to transfect for 4 h, and then the media was replaced with 100 μL of cDMEM. After 24 h from the initial transfection, 50 μL of media was removed from each well, and 50 μL of ONE-Glo™

D-luciferin substrate (Promega, UK) was added and mixed well. Then, the total volume of 100 μL was transferred to a white 96-well plate (Costar) and analyzed on a FLUOstar Omega plate reader

(BMG LABTECH, UK), and background from to the media control wells subtracted. RNASE PROTECTION ASSAY In order to assess how well complexation on the interior/exterior of the LNP protected

saRNA from degradation, samples were analyzed using an RNAse protection assay, similar to a method previously described [4]. A total of 3.8 mAU of RNAse (Life Technologies) per μg of RNA was

added to the formulations and incubated for 30 min at room temperature. An identical formulation with no RNAse treatment was included as a negative control. RNAse was then inactivated using

6.4 mAU of proteinase K (New England Biolabs, UK) per μg RNA at 55 °C for 10 min. After inactivation, saRNA was extracted using a 1:1 (v/v) mixture of sample to 25:14:1 (v/v/v)

phenol:chloroform:isoamyl alcohol. The extraction was performed by vortexing the solution well, and then centrifuging at 14,000× RPM for 10 min. The aqueous phase was removed by pipetting

and mixed with NorthernMax Gly sample Loading Dye (Thermo Fisher, UK). The samples were then incubated at 75 °C for 10 min to denature the saRNA. A 1.2% agarose gel with 1× NorthernMax

running buffer (Thermo Fisher) was prepared and allowed to completely cool before submerging in 1× NorthernMax running buffer. The samples were then added to the gel, and ran against Ambion

Millenium RNA ladder (Thermo Fisher) at 120 V for 30 min. The gel was then imaged on a GelDoc-It2 (UVP, UK), and the intensity of the degraded and nondegraded bands was quantified using

ImageJ (National Institutes of Health, USA). The % protection was defined as follows: $${\mathrm{\% }}\,{\rm{Protection}} = 100 \ast \frac{{\rm{Intensity}}_{{\rm{RNAse}}\, {\rm{Treated}}\,

{\rm{Sample}}}}{{\rm{Intensity}}_{{\rm{Naive}}\,{\rm{Sample}}}}$$ IN VIVO LUCIFERASE IMAGING Female BALB/c mice (Charles River, UK), 6–8 weeks of age, were placed into groups of _n_ = 5 and

housed in a fully acclimatized room. All animals were handled in accordance with the UK Home Office Animals Scientific Procedures Act of 1986 in accordance with an internal ethics board and

a UK government-approved project and personal license. No randomization was used to determine how samples or animals were allocated to experimental groups. Researchers were blinded to group

numbers while assessing the outcome by using generic group numbers. Group sizes were calculated to detect a difference of 1,000,000 relative light units (RLU) with a standard deviation of

200,000 RLU with a power of 0.9 and _α_ = 0.05. Food and water were supplied ad libitum. Mice were injected intramuscularly (IM) in both hind leg quadriceps muscles with 5 μg of fLuc saRNA

formulated either on the interior or exterior of C12-200, DDA, or DOTAP LNPs. After 7 days, the mice were injected intraperitoneally with 100 μL of XenoLight RediJect D-Luciferin Substrate

(Perkin Elmer, UK) and allowed to rest for 10 min. Mice were then anesthetized using isoflurane and imaged on an In Vivo Imaging System FX Pro (Kodak Co., Rochester, NY, USA) equipped with

Molecular Imaging Software Version 5.0 (Carestream Health, USA) for 10 min. A signal from each injection site was quantified using an equal detection area, using Molecular Imaging Software,

and expressed as RLU. IMMUNOGENICITY STUDY Female BALB/c mice (Charles River, UK), 6–8 weeks of age, were placed into groups of _n_ = 5. No randomization was used to determine how samples or

animals were allocated to experimental groups. Researchers were blinded to group numbers while assessing the outcome by using generic group numbers. Group sizes were calculated to detect a

difference of 200 ng/mL with a standard deviation of 40 ng/mL, with a power of 0.9 and _α_ = 0.05. Mice were immunized IM in one hind leg quadriceps muscle with 5 μg of HIV-1 Env

gp140-encoding saRNA formulated either on the interior or exterior of C12-200, DDA, or DOTAP LNPs to a total injection volume of 50 μL in 1× PBS and boosted with the identical formulation

after 3 weeks. Tail bleeds were collected prior to each vaccination and 2 weeks after the boost injection. Blood was collected and centrifuged at 10,000× RPM for 5 min. The serum was

harvested and stored at −20 °C. HIV-1 ENV GP140-SPECIFIC ELISA A semiquantitative immunoglobulin IgG ELISA protocol was performed as previously described [30]. Briefly, 1 μg/mL of

recombinant HIV-1 Env gp140 in PBS was coated onto ELISA plates, and standards were prepared by coating ELISA plate wells with anti-mouse Kappa (1:1000) and Lambda (1:1000) light chain

(Southern Biotech, UK) in PBS. Plates were then blocked with 1% BSA/0.05% Tween-20 in PBS. After washing, diluted samples and purified IgG (Southern Biotech, UK) starting at 1000 ng/mL and

titrating down the plate with fivefold dilution series were added to the plates, incubated for 1 h, and washed. A 1:2000 dilution of anti-mouse IgG-HRP (Southern Biotech, UK) was used for

detection, and plates were developed using TMB (3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenidine), and the reaction was stopped after 5 min with Stop solution (Insight Biotechnologies, UK). Absorbance was read

on a spectrophotometer (VersaMax, Molecular Devices) with SoftMax Pro GxP v5 software. STATISTICAL ANALYSIS Graphs and statistics were prepared in GraphPad Prism, version 7.0. Statistical

differences were analyzed using a one-way ANOVA adjusted for multiple comparisons or a two-tailed, unpaired _t_-test with _α_ = 0.05 used to indicate significance. RESULTS EFFECT OF

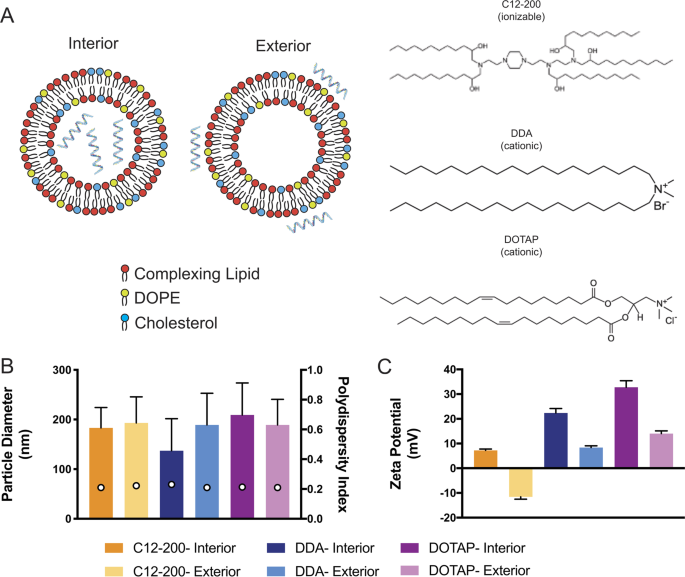

INTERIOR/EXTERIOR SARNA COMPLEXATION ON LNP SIZE, SURFACE CHARGE, AND MORPHOLOGY After preparing the formulations with saRNA either on the interior or exterior of the particle (Fig. 1), we

first sought to characterize how the different lipids, including C12-200 (ionizable), DDA (cationic), and DOTAP (cationic), affect the particle size and surface charge of these formulations

(Fig. 1b, c). We observed that regardless of complexation to the interior or exterior of the LNPs, the average particle diameter was similar (~100–200 nm) (Fig. 1b, c). All LNPs were

observed to have a similar PDI of ~0.2, indicating that there was a consistent range of particle sizes, irrespective of the arrangement of the saRNA. In addition, surface charge is an

indicator of what is accessible at the surface of the particle, a negative charge indicating that the surface of the particle is mostly covered by RNA, while a positive charge indicates that

the complexing lipids have not been saturated by RNA adsorption [31]. We found that the LNPs with encapsulated saRNA all had a positive surface, ranging from 8 to 30 mV, with DOTAP LNPs

having the most positive surface charge (Fig. 1c). For the LNPs with saRNA adsorbed to the surface of the particle, both DDA and DOTAP had positive surface charges, ranging from 8 to 15 mV.

In contrast, the C12-200 LNPs with saRNA on the exterior had a negative surface charge of −10 mV, thus indicating that the cations were quenched by the amount of RNA present in the

formulation. The morphology was assessed using TEM, as shown in Fig. 2. The particles all exhibited a rounded morphology, with particle diameters equivalent to the NTA particle size

characterization (~100–200 nm). Overall, we observed that the positioning of the saRNA on the interior or exterior of the LNPs has a limited effect on the size or PDI, and that for all the

LNPs except the “C12-200 Exterior” condition, the exterior lipid was accessible and not saturated by saRNA. EFFECT OF COMPLEXATION POSITION ON TRANSFECTION EFFICIENCY IN THE PRESENCE OF FCS

AND RNASE The formulations of fLuc-encoding saRNA were transfected into HEK293 cells, in order to determine the transfection efficiency of each formulation, and the role of the complexing

lipid (Fig. 3). First, we tested the formulations under standard transfection conditions, which includes using a transfection media that does not contain FCS, which is known to bind to

polyplexes and potentially decrease the transfection efficiency (Fig. 3). Based on the luciferase expression, we observed that the transfection efficiency of saRNA complexed to the exterior

of C12-200 LNPs was ~2 orders of magnitude lower than when the saRNA was encapsulated within the C12-200 LNP (106 RLU vs. 104 RLU). However, the opposite trend was true for the cationic

lipids, DDA and DOTAP, wherein complexing the saRNA to the exterior of the LNP resulted in higher transfection efficiency (~106 RLU) compared with encapsulation within the particle (105

RLU). Interestingly, including 50% FCS in the transfection, intended to mimic the high-protein conditions in vivo, did not inhibit the transfection efficiency, as we observed that all

conditions had equivalent luciferase expression to the standard transfection conditions. Finally, we tested the formulations in a transfection, wherein exogenous RNAse was added in order to

determine whether formulations subjected to a high amount of RNAse adequately protected the complexed RNA from degradation prior to cellular uptake. Remarkably, all the formulations besides

the “C12-200 Exterior” LNPs did not exhibit decreased transfection efficiency in the presence of RNAse. Nevertheless, the transfection efficiency of the “C12-200 Exterior” LNPs decreased

from 104 RLU to 10 RLU. Overall, the C12-200 LNPs with encapsulated RNA and both the interior/exterior complexed DDA and DOTAP LNPs showed high transfection efficiency in vitro, with no loss

of transfection in the presence of FCS and minimal degradation of the complexed saRNA prior to cellular uptake and expression. INTERIOR/EXTERIOR COMPLEXATION PROTECT FROM RNASE DEGRADATION

After observing that the transfection efficiency of exteriorly complexed saRNA on C12-200 LNPs, but not DDA or DOTAP LNPs, was inhibited by RNAse, we sought to characterize how well each of

the formulations protected the saRNA from RNAse. Thus, we added RNAse directly to the formulation, and normalized the remaining amount of undegraded RNA to an equivalent sample that was not

treated with RNAse (Fig. 4). We observed that the same amount of RNAse added to naked RNA completely degraded the RNA within 30 min. The C12-200 with encapsulated RNA protected the RNA

almost 100%, while only ~10% of the RNA adsorbed to the outside of C12-200 LNPs was protected from degradation. These results mirror the decreased transfection efficiency of “C12-200

Exterior” LNPs in the presence of RNAse (Fig. 3). Similarly, for the DOTAP LNPs, almost 100% of the encapsulated saRNA was protected from RNAse degradation, whereas only ~45% of the

exteriorly complexed saRNA remained intact after RNAse treatment. However, for the DDA LNPs, the opposite trend was observed, with only ~60% of the encapsulated saRNA protected from

degradation, whereas ~95% of the saRNA adsorbed to the surface was protected. These results show that complexation to the surface of LNPs can be equally effective at protecting saRNA from

degradation by RNAse as encapsulation within the LNP, but that it depends on the complexing lipid. IN VIVO LNP DELIVERY OF FLUC SARNA Given the high efficiency of our in vitro transfections,

we wanted to characterize whether these formulations were capable of delivering saRNA in vivo, as it has been well established in the field that in vitro results are often non-predictive

[32]. Female mice were injected with C12-200, DDA, and DOTAP formulations with saRNA on the interior or exterior of LNPs in both hind leg quadriceps muscles. Animals were then imaged for

luciferase expression at day 7 (Fig. 5), as this was previously shown to be the peak luciferase expression for the VEEV replicon [33]. We observed that similarly to the in vitro transfection

data (Fig. 3), the C12-200 LNPs with saRNA on the interior had significantly higher luciferase expression (~106 RLU, _p_ = 0.0045) than when saRNA was adsorbed to the surface (~104 RLU).

For the DDA LNPs, the opposite trend was observed; when saRNA was complexed to the exterior, the luciferase expression was significantly higher (~106 RLU, _p_ = 0.0012) than when

encapsulated within the LNP (~105 RLU). Interestingly, DOTAP showed no difference between interiorly and exteriorly complexed saRNA, as both conditions yielded a luciferase expression of

~105 RLU (_p_ = 0.187). The “C12-200 Interior” and “DDA Exterior” formulations had the highest overall luciferase expression (~106 RLU) and were not significantly different from each other

(_p_ = 0.230). These data reinforce that saRNA can be efficiently delivered in vivo when either encapsulated in LNPs with an ionizable lipid or complexed to the surface of LNPs formulated

with a cationic lipid. Moreover, we demonstrate that the identity of the cationic lipid used in the LNP formulation is an important factor that modulates delivery efficiency. IMMUNOGENICITY

OF INTERIORLY OR EXTERIORLY COMPLEXED HIV-1 ENV GP140-ENCODING SARNA After observing differential luciferase expression associated with the different LNP formulations in vivo, we sought to

test whether these variations are reflected in the immunogenicity of saRNA vaccines. Female mice were injected with C12-200, DDA, and DOTAP LNP formulations with saRNA encoding HIV-1 Env

gp140, as a model antigen, either on the interior or exterior of the particles. Mice received a prime injection, and then a boost after 3 weeks. HIV-1 Env gp140-specific IgG antibody titers

were quantified at week 3, prior to the boost injection, and 2 weeks after the final injection at week 5 (Fig. 6). We observed similar IgG titers for each of the LNP formulations, with saRNA

encapsulated within the particle (C12-200 In, DDA In, and DOTAP In), which increased by ~1 order of magnitude after a second injection. There was no HIV-1 Env gp140-specific IgG detected

for the “C12-200 Exterior” formulation at either 3 or 5 weeks, which reflects the minimal in vivo luciferase expression we observed (Fig. 5). Interestingly, for both of the cationic LNP

formulations (DDA Exterior and DOTAP Exterior), the IgG titers reached peak levels after a single injection. Despite trending differences between the formulations, none of the groups were

statistically significantly different, as assessed by ANOVA adjusted for multiple comparisons. Overall, these results show that the formulations with encapsulated RNA induce equivalent IgG

antibody responses against HIV-1 Env gp140, which were enhanced after a second injection, while the cationic formulations with exteriorly complexed saRNA achieved maximal IgG titers after a

single injection. DISCUSSION Here, we show that LNPs formulated with cationic lipids and saRNA adsorbed to the surface efficiently deliver RNA in vitro and in vivo, with equivalent protein

expression to LNPs formulated with an ionizable lipid and encapsulated RNA. Furthermore, despite RNA being exposed on the surface of the particles, we show that cationic lipids are able to

complex, condense, and protect the RNA from RNAse degradation. In addition, we observed that cationic LNPs delivered saRNA in vivo, but that the composition of the cationic lipid is also a

factor, as the delivery efficiency of DDA LNPs was significantly higher than DOTAP LNPs. Finally, both cationic LNPs with surface-adsorbed HIV-1 Env gp140 saRNA were shown to induce antibody

responses that were equivalent to saRNA formulated on the interior of ionizable LNPs. What are the potential benefits from complexing the saRNA on the surface, as opposed to encapsulating

it within LNPs? One potential advantage is that a comprehensive quality control panel can be performed on a batch of LNPs, prior to the addition of RNA, which can then be incorporated at

100% efficiency. However, the main potential advantage is that this provides flexibility for complexing with different RNA constructs, as performed in these studies (Figs. 5 and 6). This

approach could be particularly useful for emergency responses, wherein a batch of LNPs can be prepared in advance for immediate formulation at the onset of an outbreak. Even with

sophisticated manufacturing instrumentation, production of LNPs at a laboratory scale can result in batch- to-batch variability, including disparate encapsulation efficiency, size, charge,

and RNAse contamination. Excluding RNA from the initial production of particles enables easily reproducible batches of LNP formulations. While the LNPs in these experiments all had similar

particle diameters, ranging from 100 to 200 nm (Fig. 1), the “C12-200 Exterior” LNPs were the sole formulation with a negative surface charge. The formulation was complexed with RNA at pH 3,

when the amine groups in the lipidoid are protonated [29], but then dialyzed in PBS for use in cell culture and animal studies. We postulate that the ionization of the lipid caused lower

retention of the RNA, which then resulted in lower transfection and in vivo delivery efficiencies, as confirmed by the failure to induce an antibody response against HIV-1 Env gp140.

Furthermore, despite saRNA complexation on the surface, the “C12-200 Exterior” LNPs were the only formulation that was susceptible to RNAse degradation during transfection (Fig. 3), although

the “DDA Interior” and “DOTAP Exterior” did not completely protect saRNA from enzymatic degradation (Fig. 4). This suggests that while the “DDA Interior” LNPs were prepared with RNA on the

interior of the particles, some of it is still present on the particle corona, although this does not seem to occur for the C12-200 or DOTAP “Interior” formulations. We observed that “DDA

Exterior” and “DOTAP Exterior” LNPs still present a positive charge with an N/P ratio of 12:1, suggesting that a higher quantity of saRNA can be complexed to the surface of these particles.

The “C12-200 Interior” and “DDA Exterior” formulations efficiently delivered saRNA in vivo (Fig. 5), in contrast to the “C12-200 Exterior” and “DDA Interior” LNPs, which were less effective

delivery vehicles. This is evidenced by lower overall or no luciferase expression, which indicates that the saRNA in these cases is being taken up randomly, resulting in a weak signal that

is amplified by the self-replicative properties of the RNA. Interestingly, the formulations with encapsulated HIV-1 Env gp140 saRNA all had equivalent serum antibody responses (Fig. 6),

while the formulations with saRNA on the surface of cationic LNPs exhibited maximal antibody titer after a single immunization and did not require boosting. While the “C12-200 Interior” and

the “DDA Exterior” LNPs had similar luciferase expression (Fig. 5), the “DDA Exterior” LNPs induced the highest antibody titers of the whole study after a single injection. This effect is

likely due to adjuvanting properties of the DDA LNPs, which have previously been shown to act as adjuvants for protein vaccines [34, 35]. This was a relatively short vaccination schedule,

and we suggest that utilizing a longer interval between vaccinations could further improve the antibody response, as this would provide more time for the protein expression to peak and

completely dissipate before boosting [4, 36]. To our knowledge, this proof-of-concept study is the first systematic comparison of LNPs with saRNA on the interior or exterior of the

particles. In order to be able to compare the formulations, we employed a single N/P ratio of 12:1, which can be further optimized for each formulation [37, 38]. It would be particularly

useful to characterize the exact distribution of saRNA for each formulation, i.e., whether the saRNA is completely encapsulated or a portion is still accessible on the surface. The presented

studies demonstrate the ability of LNPs to efficiently complex and deliver saRNA complexed on the surface of the particle, which presents an alternative approach to the paradigm of

encapsulating RNA. REFERENCES * Petsch B, Schnee M, Vogel AB, Lange E, Hoffmann B, Voss D, et al. Protective efficacy of in vitro synthesized, specific mRNA vaccines against influenza A

virus infection. Nat Biotechnol. 2012;30:1210. Article CAS Google Scholar * Pardi N, Parkhouse K, Kirkpatrick E, McMahon M, Zost SJ, Mui BL, et al. Nucleoside-modified mRNA immunization

elicits influenza virus hemagglutinin stalk-specific antibodies. Nat Commun. 2018;9:3361. Article Google Scholar * Schnee M, Vogel AB, Voss D, Petsch B, Baumhof P, Kramps T, et al. An mRNA

vaccine encoding rabies virus glycoprotein induces protection against lethal infection in mice and correlates of protection in adult and newborn pigs. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10:e0004746.

PubMed PMID: PMC4918980 Article Google Scholar * Geall AJ, Verma A, Otten GR, Shaw CA, Hekele A, Banerjee K. et al. Nonviral delivery of self-amplifying RNA vaccines. Proc Natl Acad Sci

USA. 2012;109:14604 Article CAS Google Scholar * Brito LA, Chan M, Shaw CA, Hekele A, Carsillo T, Schaefer M, et al. A cationic nanoemulsion for the delivery of next-generation RNA

vaccines. Mol Ther. 2014;22:2118–29. PubMed PMID: PMC4429691 Article CAS Google Scholar * Bogers WM, Oostermeijer H, Mooij P, Koopman G, Verschoor EJ, Davis D, et al. Potent immune

responses in rhesus macaques induced by nonviral delivery of a self-amplifying RNA vaccine expressing HIV type 1 envelope with a cationic nanoemulsion. J Infect. Dis. 2015;211:947–55. PubMed

PMID: PMC4416123 Article CAS Google Scholar * Brito LA, Kommareddy S, Maione D, Uematsu Y, Giovani C, Berlanda Scorza F, et al. Chapter seven—self-amplifying mRNA vaccines. In: Huang L,

Liu D, Wagner E, editors. Advances in Genetics. 2015;89: 179–233. * Pardi N, Hogan MJ, Pelc RS, Muramatsu H, Andersen H, DeMaso CR, et al. Zika virus protection by a single low dose

nucleoside modified mRNA vaccination. Nature. 2017;543:248–51. PubMed PMID: PMC5344708 Article CAS Google Scholar * Chahal JS, Khan OF, Cooper CL, McPartlan JS, Tsosie JK, Tilley LD, et

al. Dendrimer-RNA nanoparticles generate protective immunity against lethal Ebola, H1N1 influenza, and Toxoplasma gondii challenges with a single dose. Proc Natl Acad Sci US A.

2016;113:E4133–E42. PubMed PMID: PMC4961123 Article CAS Google Scholar * Sebastian M, Papachristofilou A, Weiss C, Früh M, Cathomas R, Hilbe W, et al. Phase Ib study evaluating a

self-adjuvanted mRNA cancer vaccine (RNActive®) combined with local radiation as consolidation and maintenance treatment for patients with stage IV non-small cell lung cancer. BMC Cancer.

2014;14:748. PubMed PMID: PMC4195907 Article Google Scholar * Kallen K-J, Heidenreich R, Schnee M, Petsch B, Schlake T, Thess A, et al. A novel, disruptive vaccination technology:

self-adjuvanted RNActive(®) vaccines. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2013;9:2263–76. PubMed PMID: PMC3906413 Article CAS Google Scholar * Uchida S, Kinoh H, Ishii T, Matsui A, Tockary TA,

Takeda KM, et al. Systemic delivery of messenger RNA for the treatment of pancreatic cancer using polyplex nanomicelles with a cholesterol moiety. Biomaterials. 2016;82:221–8. Article CAS

Google Scholar * Oberli MA, Reichmuth AM, Dorkin JR, Mitchell MJ, Fenton OS, Jaklenec A, et al. Lipid nanoparticle assisted mRNA delivery for potent cancer immunotherapy. Nano Lett.

2017;17:1326–35. PubMed PMID: PMC5523404 Article CAS Google Scholar * Pardi N, Hogan MJ, Porter FW, Weissman D. mRNA vaccines—a new era in vaccinology. Nat Rev Drug Discov.

2018;17:261–79. PubMed PMID: PMC5906799 Article CAS Google Scholar * Fleeton MN, Chen M, Berglund P, Rhodes G, Parker SE, Murphy M, et al. Self-replicative RNA vaccines elicit protection

against influenza A virus, respiratory syncytial virus, and a tickborne encephalitis virus. J Infect Dis. 2001;183:1395–8. Article CAS Google Scholar * Pushko P, Parker M, Ludwig GV,

Davis NL, Johnston RE, Smith JF. Replicon-helper systems from attenuated Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus: expression of heterologous genesin vitroand immunization against heterologous

pathogens in vivo. Virology. 1997;239:389–401. Article CAS Google Scholar * Démoulins T, Milona P, Englezou PC, Ebensen T, Schulze K, Suter R, et al. Polyethylenimine-based polyplex

delivery of self-replicating RNA vaccines. Nanomedicine. 2016;12:711–22. Article Google Scholar * Brazzoli M, Magini D, Bonci A, Buccato S, Giovani C, Kratzer R, et al. Induction of

broad-based immunity and protective efficacy by self-amplifying mRNA vaccines encoding influenza virus hemagglutinin. J Virol. 2016;90:332–44. PubMed PMID: PMC4702536 Article CAS Google

Scholar * Bahl K, Senn JJ, Yuzhakov O, Bulychev A, Brito LA, Hassett KJ, et al. Preclinical and clinical demonstration of immunogenicity by mRNA vaccines against H10N8 and H7N9 influenza

viruses. Mol Ther. 2017;25:1316–27. PubMed PMID: PMC5475249 Article CAS Google Scholar * Kranz LM, Diken M, Haas H, Kreiter S, Loquai C, Reuter KC, et al. Systemic RNA delivery to

dendritic cells exploits antiviral defence for cancer immunotherapy. Nature. 2016;534:396. Article Google Scholar * Morrison C. Alnylam prepares to land first RNAi drug approval. Nat Rev

Drug Discov. 2018;17:156. Article CAS Google Scholar * Kauffman KJ, Dorkin JR, Yang JH, Heartlein MW, DeRosa F, Mir FF, et al. Optimization of lipid nanoparticle formulations for mRNA

delivery in vivo with fractional factorial and definitive screening designs. Nano Lett. 2015;15:7300–6. Article CAS Google Scholar * Pereira P, Jorge AF, Martins R, Pais AACC, Sousa F,

Figueiras A. Characterization of polyplexes involving small RNA. J Colloid Interface Sci.2012;387:84–94. Article CAS Google Scholar * Love KT, Mahon KP, Levins CG, Whitehead KA, Querbes

W, Dorkin JR, et al. Lipid-like materials for low-dose, in vivo gene silencing. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:1864–9. Article CAS Google Scholar * Agger EM, Rosenkrands I, Hansen J,

Brahimi K, Vandahl BS, Aagaard C, et al. Cationic liposomes formulated with synthetic mycobacterial cordfactor (CAF01): a versatile adjuvant for vaccines with different immunological

requirements. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e3116. PubMed PMID: PMC2525815 Article Google Scholar * Pollard C, Rejman J, De Haes W, Verrier B, Van Gulck E, Naessens T, et al. Type I IFN counteracts the

induction of antigen-specific immune responses by lipid-based delivery of mRNA vaccines. Mol Ther. 2013;21:251–9. PubMed PMID: PMC3538310 Article CAS Google Scholar * Blakney AK, McKay

PF, Shattock RJ. Structural components for amplification of positive and negative strand VEEV splitzicons. Front Mol Biosci. 2018;5:71. PubMed PMID: 30094239. eng. Article Google Scholar *

Aldon Y, McKay PF, Allen J, Ozorowski G, Felfödiné Lévai R, Tolazzi M, et al. Rational design of DNA-expressed stabilized native-like HIV-1 envelope trimers. Cell Rep. 2018;24:3324–38.e5.

Article CAS Google Scholar * Love KT, Mahon KP, Levins CG, Whitehead KA, Querbes W, Dorkin JR, et al. Lipid-like materials for low-dose, in vivo gene silencing. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

2010;107:1864–9. PubMed PMID: PMC2804742 Article CAS Google Scholar * Badamchi-Zadeh A, McKay PF, Holland MJ, Paes W, Brzozowski A, Lacey C, et al. Intramuscular immunisation with

chlamydial proteins induces chlamydia trachomatis specific ocular antibodies. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0141209. PubMed PMID: PMC4621052 Article Google Scholar * Schubert MA, Müller-Goymann CC.

Characterisation of surface-modified solid lipid nanoparticles (SLN): Influence of lecithin and nonionic emulsifier. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2005;61:77–86. Article CAS Google Scholar * Guan

S, Rosenecker J. Nanotechnologies in delivery of mRNA therapeutics using nonviral vector-based delivery systems. Gene Ther. 2017;24:133. Article CAS Google Scholar * Vogel AB, Lambert L,

Kinnear E, Busse D, Erbar S, Reuter KC, et al. Self-amplifying RNA vaccines give equivalent protection against influenza to mRNA vaccines but at much lower doses. Mol Ther. 2018;26:446–55.

Article CAS Google Scholar * Nordly P, Rose F, Christensen D, Nielsen HM, Andersen P, Agger EM, et al. Immunity by formulation design: Induction of high CD8+ T-cell responses by poly(I:C)

incorporated into the CAF01 adjuvant via a double emulsion method. J Control Release. 2011;150:307–17. Article CAS Google Scholar * Christensen D, Korsholm KS, Andersen P, Agger EM.

Cationic liposomes as vaccine adjuvants. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2011;10:513–21. Article CAS Google Scholar * Cosgrove CA, Lacey CJ, Cope AV, Bartolf A, Morris G, Yan C, et al. Comparative

immunogenicity of HIV-1 gp140 vaccine delivered by parenteral, and mucosal routes in female volunteers; MUCOVAC2, a randomized two centre study. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0152038. PubMed PMID:

PMC4861263 Article Google Scholar * Kubota K, Onishi K, Sawaki K, Li T, Mitsuoka K, Sato T, et al. Effect of the nanoformulation of siRNA-lipid assemblies on their cellular uptake and

immune stimulation. Int J Nanomed. 2017;12:5121–33. PubMed PMID: PMC5529365 Article CAS Google Scholar * McCullough KC, Milona P, Thomann-Harwood L, Démoulins T, Englezou P, Suter R, et

al. Self-amplifying replicon RNA vaccine delivery to dendritic cells by synthetic nanoparticles. Vaccines. 2014;2:735–54. PubMed PMID: PMC4494254 Article CAS Google Scholar Download

references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We gratefully acknowledge the Dormeur Investment Service Ltd. for providing funds to purchase equipment used in these studies. FUNDING Funding AKB is supported by

a Whitaker Post-Doctoral Fellowship and a Marie Skłodowska Curie Individual Fellowship funded by the European Commission H2020 (No. 794059). BIY, YA, PFM, and RJS are funded by the European

Union’s Horizon 2020 for Research & Innovation program under grant agreement no. 681137 and the U.K. Department of Health and Social Care for funding the Future Vaccine Manufacturing

Hub through the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC, grant number: EP/R013764/1). AUTHOR INFORMATION AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Department of Medicine, Imperial College

London, London, UK Anna K. Blakney, Paul F. McKay, Bárbara Ibarzo Yus, Yoann Aldon & Robin J. Shattock Authors * Anna K. Blakney View author publications You can also search for this

author inPubMed Google Scholar * Paul F. McKay View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Bárbara Ibarzo Yus View author publications You can also

search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Yoann Aldon View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Robin J. Shattock View author

publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to Robin J. Shattock. ETHICS DECLARATIONS CONFLICT OF INTEREST The authors

declare that they have no conflict of interest. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION PUBLISHER’S NOTE: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and

institutional affiliations. RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS OPEN ACCESS This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing,

adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons

license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a

credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted

use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Reprints and permissions ABOUT

THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Blakney, A.K., McKay, P.F., Yus, B.I. _et al._ Inside out: optimization of lipid nanoparticle formulations for exterior complexation and in vivo delivery of

saRNA. _Gene Ther_ 26, 363–372 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41434-019-0095-2 Download citation * Received: 05 April 2019 * Revised: 18 May 2019 * Accepted: 28 June 2019 * Published: 12

July 2019 * Issue Date: September 2019 * DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41434-019-0095-2 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content: Get

shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative