Play all audios:

In a recent note, Jensen and Lynch (2020) remarked on the role of “mutational meltdown” as a strategy to restrict the expansion of COVID-19 in human populations. Mutational meltdown is a

well-known population genetics process by which a population may become extinct due to the accumulation of deleterious mutations (Lynch and Gabriel 1990). As explained by Jensen and Lynch

(2020), a sufficiently large increase of mutation rate may lead to a spiral of decline in fitness that eventually causes the extinction of the population. In a separate body of literature,

virologists refer to that process as “lethal mutagenesis” in the context of drug-induced increase in viral mutation rate (Bull et al. 2007). Based on that concept, the development of drug

therapies to induce errors during virus replication, either by lowering its RNA polymerase fidelity or by using base analogs, may become a promising strategy to fight viruses (such as

SARS-CoV-2). An additional issue related to the above argument is the role of recombination. Muller (1964) emphasized that in species devoid of recombination the accumulation of mutations is

higher than in species with sexual reproduction. In the latter case, deleterious mutations can be assembled in the same genome by recombination, facilitating their efficient elimination. In

contrast, in the absence of recombination, mutations accumulate without the possibility of reconstructing genomes with a mutation number lower than the minimum present in a given

generation. This process, known as Muller’s ratchet, is a consequence of the action of purifying selection, which ultimately leads to a strong reduction in effective population size

(_N__e_); i.e., an increase of genetic drift and a consequent increase in the rate of fixation of combinations of deleterious mutations. Conceptually, _N__e_ refers to the number of

individuals that effectively contribute to descendants in the long term which, under selection, can be much smaller than the population census size _N_. Muller’s ratchet can be considered as

part of the more general theory of “background selection,” which predicts the reduction of _N__e_ by the action of purifying selection on linked sites (Charlesworth 2013) and applies to

both sexual and asexual species. Santiago and Caballero (2016) showed that the rate of accumulation of deleterious mutations, extended to any degree of recombination, can be predicted from

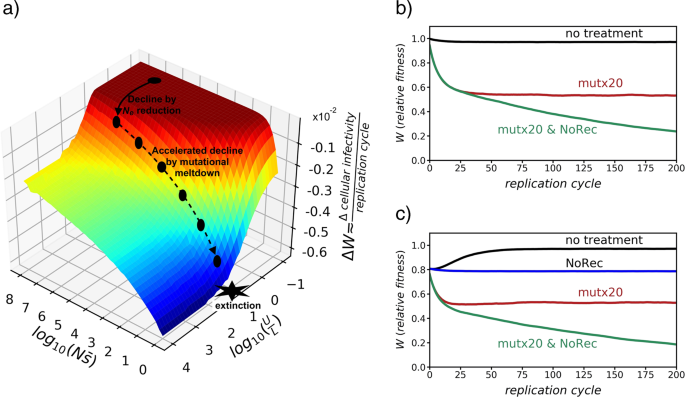

the effective population size theory of selection on linked sites and Kimura (1957) equations for the probability of fixation of mutations. Thus, the mean rate of decline in fitness (_W_)

can be predicted (Fig. 1a) as a function of four factors: the population size (_N_); the average effect of deleterious mutations (\(\bar s\)); the rate of recombination, reflected here by

the recombination map length (_L_) across the genome; and the overall genomic rate of deleterious mutations (_U_), the latter being proportional to the genome size and to the mutation rate

per site. Coronaviruses have two characteristics that allow them to have the largest genomes among RNA viruses: an RNA polymerase with proofreading activity; and a homologous recombination

mechanism associated with replication, which is effectively equivalent to sexual reproduction. These features entail a relatively low mutation rate and a high efficiency in eliminating

deleterious mutations from the population of viral particles, which opens up the possibility of having large and sophisticated genomes. Although no direct measures of recombination rates are

available for SARS-CoV-2, estimates from betacoronavirus mouse hepatitis virus (MHV) (Baric et al. 1995) suggest that, on average, they could be on the order of 10−5 between two consecutive

sites per replication cycle. This quantity is approximately equivalent to a recombination map length of _L_ = 0.3 Morgans, given that the genome of coronaviruses is about 30,000 nt long. On

the other hand, mutation rates in MHV are on the order of 10−6 substitutions per site per replication cycle (Eckerle et al. 2010). Assuming that most mutations are deleterious or slightly

deleterious, this is equivalent to a genomic rate of deleterious mutations probably close to _U_ = 0.03. As for any other successful population with an equivalent to sexual reproduction,

coronavirus populations naturally stand at equilibrium somewhere on the upper plain of the surface of fitness changes in Fig. 1a. There is no steady decline of fitness on this plain, as

virtually all deleterious mutations are eventually eliminated from the population. Given the above rates of mutation and recombination, the _U_/_L_ ratio for coronaviruses could be about

0.1. The location on the surface in Fig. 1a is also determined by the product \(N\bar s\), which is particularly important when _N_ is transitorily small, as in the case of infection passage

on a new host cell or individual (Duarte et al. 1992). However, for the moment, we shall consider that the product \(N\bar s\) is sufficiently large to avoid any decline of fitness, and a

feasible location for coronaviruses could be the black dot represented on the upper plain in Fig. 1a. If the mutation rate _U_ is increased, the equilibrium is pushed in the direction of the

first arrow along the _U_/_L_ axis to the second black dot, implying an acceleration in the rate of fitness decline of the population (in Fig. 1, given as infectivity rate) by accumulation

of deleterious mutations. This accumulation is a consequence of the reduction of _N__e_, but does not imply a reduction in population size _N_ in the first stage. Then, as a consequence of

the continuous accumulation of mutations, the population becomes trapped into a spiral of decline in fitness, which leads to a path of consecutive reductions of population size _N_ in the

direction of the second broken arrow along the \(N\bar s\) axis, which eventually ends with the extinction, as explained by Jensen and Lynch (2020). Recombination in coronaviruses makes the

strategy of increasing the mutation rate less efficient than in the case of asexual reproduction. The success of this strategy depends on how close to the cliff the population is at

equilibrium in Fig. 1a and how long the push is in the direction of the first arrow. Given that the location of the equilibrium point of the population on the plain depends on the ratio

_U_/_L_, an increase in _U_ would cause an equivalent effect to a similar decrease in _L_. The relevant point is that simultaneous changes in _U_ and _L_ have multiplicative effects on the

displacement on the surface. In other words, an increase in the mutation rate may not be sufficient by itself to “knock down” the population, but if it is combined with the reduction in the

recombination rate, the effect is amplified. Although it is unknown the extent to which both factors are functionally independent of each other in coronaviruses, it has been shown that some

mutations can affect the rate of recombination without altering replication fidelity, for example, in polioviruses (Xiao et al. 2016). While Fig. 1a represents equilibrium points of

populations for particular combinations of parameters, Fig. 1b illustrates the temporal evolution of the absolute value of fitness over the infection process under three different scenarios:

no treatment applied; a 20-fold increased mutation rate (mut × 20); and two treatments combined 20-fold increased mutation rate and complete restriction of recombination (mut × 20 &

NoRec). The joint application of both treatments increases the magnitude of fitness drop when compared with the single treatment for mutation. The example assumes a constant population size

of _N_ = 1000 and constant deleterious effect _s_ = 0.1, the latter being the average estimate for a variety of viruses (Sanjuán 2010). It is expected that _N_ would be reduced over

generations, accelerating the fitness decline. Thus, the example is a conservative one from that point of view. However, a substantially large deleterious effect is assumed for the purpose

of illustration. Smaller mutational effects would imply a lower impact of both increased mutations and reduced recombination. In addition, other possible factors, such as advantageous

mutations, compensatory mutations or epistasis are not considered in the model. To date, no drug is known targeting the recombination process in coronaviruses and its development does not

seem to be a priority either. However, the fact is that recombination rate in RNA viruses is determined by a variety of host factors affecting RNA metabolism, RNA silencing and the structure

of the compartments where the viruses replicate (e.g. Garcia-Ruiz et al. (2018)). This evidence suggests that recombination processes could be feasible targets to develop new antivirals.

Recombination may also impact the spread of viruses across human populations through the effect of coinfections, as well known by epidemiologists (Balmer and Tanner 2011) and also documented

for SARS-CoV-2 (Yi 2020). Coinfections by different genotypes are expected to result in the generation of new adaptive variants. In parallel, considering that most mutations are

deleterious, the general principles described above can also be contemplated from an epidemiological perspective. To some extent, consecutive transmissions between community members result

in increased load of deleterious mutations (Drop et al. 2020), but coinfections of the same cell by different strains could counteract that effect by allowing for the emergence of new

genotypes with reduced mutational load. Here, the role of coinfections is equivalent to the effect of sexual reproduction on the accumulation of deleterious mutations. This is shown in Fig.

1c where two viral lineages are assumed to coinfect the host. The effect of recombination (no treatment) is a substantial recovery of the population fitness, which can be avoided if

recombination is restricted or completely avoided. Thus, from Fig. 1c, it can be deduced that coinfection by different strains of a virus with substantial recombination implies an advantage

for the virus and, thus, a high risk for the host. In conclusion, our intention has been to point out the generally unnoticed issue that a combination of increased mutation and reduced

recombination may produce an accelerated fitness decline of viruses in which recombination is not negligible. This is a point that may be further considered by virologists in order to look

for new strategies to cope with viral proliferation. REFERENCES * Balmer O, Tanner M (2011) Prevalence and implications of multiple-strain infections. Lancet Infect Dis 11:868–878 Article

Google Scholar * Baric RS, Fu K, Chen W, Yount B (1995) High recombination and mutation rates in mouse hepatitis virus suggest that coronaviruses may be potentially important emerging

viruses. In: Talbot PJ, Levy GA (eds) Corona and related viruses. Plenum Press, New York, p 571–576 * Bull JJ, Sanjuan R, Wilke CO (2007) Theory of lethal mutagenesis for viruses. J Virol

81:2930–2939 Article CAS Google Scholar * Charlesworth B (2013) Background selection 20 years on. J Hered 104:161–171 Article Google Scholar * Drop L, Acman M, Richard D, Shaw LP, Ford

CE, Ormond L, et al. (2020) Emergence of genomic diversity and recurrent mutations in SARS-CoV-2. Infect Genet Evol https://doi.org/10.1016/j.meegid.2020.104351 * Duarte E, Clarke D, Moya A,

Domingo E, Holland J (1992) Rapid fitness losses in mammalian RNA virus clones due to Muller’s ratchet. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 88:6015–6019 Article Google Scholar * Eckerle LD, Becker MM,

Halpin RA, Li K, Venter E et al. (2010) Infidelity of SRAS-CoV Nsp14-exonuclease mutant virus replication is revealed by complete genome sequencing. PLoS Pathog 6:e1000896 Article Google

Scholar * Garcia-Ruiz H, Diaz A, Ahlquist P (2018) Intermolecular RNA recombination occurs at different frequencies in alternate forms of brome mosaic virus RNA replication compartments.

Viruses 10:131 Article Google Scholar * Jensen JD, Lynch M (2020) Considering mutational meltdown as a potential SARS-CoV-2 treatment strategy. Heredity 38:226–231 Google Scholar * Kimura

M (1957) Some problems of stochastic processes in genetics. Ann Math Stat 28:882–901 Article Google Scholar * Lynch M, Gabriel W (1990) Mutation load and the survival of small

populations. Evolution 44:1725–1737 Article Google Scholar * Muller HJ (1964) The relation of recombination to mutational advance. Mutat Res 1:2–9 Article Google Scholar * Sanjuán R

(2010) Mutational fitness effects in RNA and single-stranded DNA viruses: common patterns revealed by site-directed mutagenesis studies. Philos Trans R Soc 365:1975–1982 Article Google

Scholar * Santiago E, Caballero A (2016) Joint prediction of the effective population size and the rate of fixation of deleterious mutations. Genetics 204:1267–1279 Article CAS Google

Scholar * Xiao Y, Rouzine IM, Blanco S, Acevedo A, Goldstein EF, Farkov M et al. (2016) RNA recombination enhances adaptability and is required for virus spread and virulence. Cell Host

Microbe 19:493–503 Article CAS Google Scholar * Yi H (2020) 2019 novel coronavirus is undergoing active recombination. Clin Infect Dis https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa219 Download

references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We thank S. F. Elena, C. López-Otín, R. Giráldez, J. J. Bull, and an anonymous referee for helpful comments on the manuscript. This research was funded by AEI

(CGL2016-75904-C2), Xunta de Galicia (ED431C 2016-037), and Fondos Feder. AUTHOR INFORMATION AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Departamento de Biología Funcional, Facultad de Biología, Universidad

de Oviedo, Oviedo, Spain Enrique Santiago * Centro de Investigación Mariña, Departamento de Bioquímica, Genética e Inmunología, Edificio CC Experimentais, Campus de Vigo, As Lagoas,

Universidade de Vigo, Marcosende, 36310, Vigo, Spain Armando Caballero Authors * Enrique Santiago View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar *

Armando Caballero View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to Enrique Santiago. ETHICS DECLARATIONS CONFLICT

OF INTEREST The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION PUBLISHER’S NOTE Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in

published maps and institutional affiliations. Associate editor: Barbara Mable RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS OPEN ACCESS This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0

International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the

source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative

Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by

statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Santiago, E., Caballero, A. The value of targeting recombination as a strategy

against coronavirus diseases. _Heredity_ 125, 169–172 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41437-020-0337-5 Download citation * Received: 24 May 2020 * Revised: 17 June 2020 * Accepted: 18 June

2020 * Published: 30 June 2020 * Issue Date: October 2020 * DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41437-020-0337-5 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read

this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative