Play all audios:

ABSTRACT Group 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2s) have tissue-resident competence and contribute to the pathogenesis of allergic diseases. However, the mechanisms regulating prolonged

ILC2-mediated TH2 cytokine production under chronic inflammatory conditions are unclear. Here we show that, at homeostasis, Runx deficiency induces excessive ILC2 activation due to overly

active GATA-3 functions. By contrast, during allergic inflammation, the absence of Runx impairs the ability of ILC2s to proliferate and produce effector TH2 cytokines and chemokines.

Instead, functional deletion of Runx induces the expression of exhaustion markers, such as IL-10 and TIGIT, on ILC2s. Finally, these ‘exhausted-like’ ILC2s are unable to induce type 2 immune

responses to repeated allergen exposures. Thus, Runx confers competence for sustained ILC2 activity at the mucosa, and contributes to allergic pathogenesis. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY

OTHERS SLAM-FAMILY RECEPTORS PROMOTE RESOLUTION OF ILC2-MEDIATED INFLAMMATION Article Open access 13 June 2024 CD200–CD200R IMMUNE CHECKPOINT ENGAGEMENT REGULATES ILC2 EFFECTOR FUNCTION AND

AMELIORATES LUNG INFLAMMATION IN ASTHMA Article Open access 05 May 2021 INTERLEUKIN-33 ACTIVATES REGULATORY T CELLS TO SUPPRESS INNATE ΓΔ T CELL RESPONSES IN THE LUNG Article 28 September

2020 INTRODUCTION Innate lymphoid cells (ILCs) are enriched in mucosal tissues, where they function as sentinel cells at the front line of host defense1. Although ILCs do not possess

rearranged antigen-specific receptors, they exert a helper function similar to TH cells by producing helper cytokines. ILCs are categorized into three main subsets: TH1-like ILC1s, TH2-like

ILC2s, and TH17/TH22-like ILC3s2,3,4,5,6. Recently, another subset of ILCs named regulatory ILCs (ILCregs) has been reported to provide an immune suppressive function by producing IL-10 in

the intestine7. ILC2s are the main population producing IL-5, which recruits eosinophils into tissues under healthy conditions8. Upon allergic stimulation, ILC2s are activated by IL-25,

IL-33, and TSLP from damaged epithelial cells, IL-2, IL-4, and IL-9 from other haematopoietic cells or from ILC2s themselves, neuropeptides, and lipid mediators1,9,10,11. Activated ILC2s

contribute to deterioration of allergic diseases by producing high levels of IL-5 and IL-13, both of which enhance the TH2 induction and inflammation mediated by eosinophils. An ILC2 subset

producing IL-10 (ILC210s) in regions of chronic or severe allergic inflammation is associated with reduction of eosinophils in the lung by unknown mechanisms12. Recurrent stimulation

influences the biological properties of ILC2s, as well as T cells. After the effector phase, T cells can become long-lived memory T cells in the tissues or lymph nodes, where they are

reactivated by the same antigen. A similar recall response was also observed in ILC2s pre-activated with IL-33 or allergens13. In contrast, T cells at sites of chronic inflammation become

exhausted and lose their effector functions, including cytokine production and proliferation, in response to repeated stimulation14. PD-1, which is a T cell exhaustion marker, is induced on

activated ILC2s and negatively regulates this cell pool15. However, PD-1+ ILC2s are not considered exhausted because they continue to produce IL-5 normally. Thus, ILC2s with a hyporesponsive

phenotype similar to exhausted T cells have not yet been identified. The mammalian Runx transcription factor protein family is composed of Runx1, Runx2, and Runx3. Each Runx protein

requires heterodimer formation with Cbfβ to bind DNA16. Runx3 is the main family member expressed in all ILC subsets and is indispensable for the differentiation and function of the ILC1 and

ILC3 subsets17. However, depletion of Runx3 alone has little effect on ILC2 differentiation, probably due to the redundant functions of other Runx proteins, such as Runx1, which is

expressed in ILC2s. Thus, the function of Runx/Cbfβ complexes in ILC2s has not been clarified. Here, we show that Runx/Cbfβ complexes are not necessary for ILC2 differentiation but modulate

ILC2 function. At steady state, Runx-deficient ILC2s are activated and aberrantly secrete IL-5, resulting in increased eosinophil recruitment to the lung. However, after allergic

stimulation, ILC2s lacking Runx fail to proliferate and produce various cytokines and chemokines but have increased expression of IL-10 and TIGIT, which are known markers of exhausted T

cells. We explore the existence of IL-10+ TIGIT+ ILC2s with low reactivity in the physiological setting and find that severe subacute allergic inflammation induces the emergence of

hyporesponsive IL-10+ TIGIT+ ILC2s, and that this effect is enhanced by Cbfβ deficiency. Collectively, our data reveal that Runx/Cbfβ complexes are required to prevent ILC2s from entering an

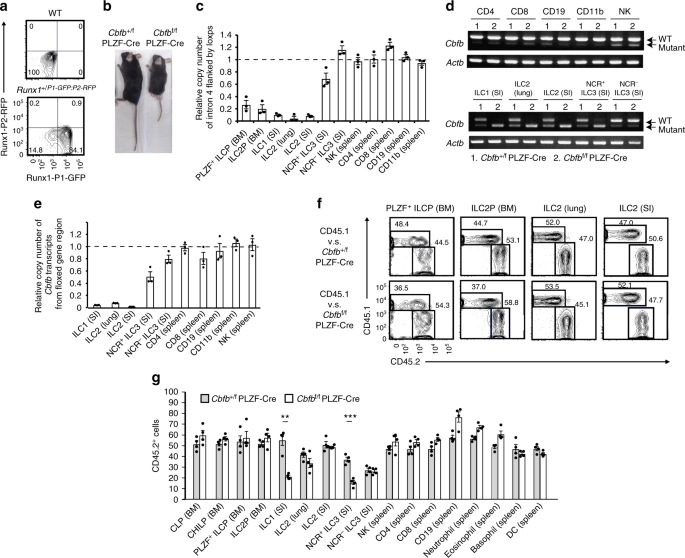

exhausted-like functional state under allergic conditions. RESULTS RUNX IS NOT REQUIRED FOR DEVELOPMENT OF ILC2S Of all of the ILCs and ILC progenitors, the highest _Runx1_ and _Runx3_ mRNA

expression levels are found in the common precursor to ILCs (ILCPs), which is marked by stage-specific PLZF expression and can differentiate into ILC1s, ILC2s, and NCR+ ILC3s (a

subpopulation of ILC3s)17. Analysis of Runx3 reporter mice suggests that downregulation of Runx3 may be required for PLZF+ ILCPs to enter the ILC2 pathway, whereas ILC1s and ILC3s require

intermediate to high levels of Runx3 for their differentiation17. To precisely examine Runx1 protein expression in ILC subsets and progenitors, we took advantage of Runx1+/P1-GFP: P2-RFP

mice, in which GFP or RFP was driven from the distal (P1) or proximal (P2) _Runx1_ promoter, respectively18. PLZF+ ILCPs utilized both the P1 and P2 promoters for high Runx1 expression,

although ILC2s in the lung and intestine expressed Runx1 from the P1 promoter to a greater extent than ILC1s and ILC3s in the intestine (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. 1). Thus, Runx1 is

expressed by ILC2s despite low Runx3 expression. To assess the roles of Runx/Cbfβ complexes in the function and differentiation of PLZF+ ILCPs into ILC2s, we deleted Cbfβ in the PLZF+ ILCPs

using PLZF-Cre (_Cbfb_f/f PLZF-Cre mice). This strategy should result in a complete loss of any Runx protein function in the descendant ILC subsets, including ILC1s, ILC2s, and NCR+ ILC3s.

The _Cbfb_f/f PLZF-Cre mice were born and grew to adults, although they were smaller than their littermate controls (Fig. 1b) and had bone distortion and difficulty walking. The defects in

bone formation may be explained by the loss of Runx2, which is critical for osteoblast differentiation, because PLZF is expressed in osteoblasts prior to Runx2 induction19. Then, we examined

which lymphocytes suffered from the Cbfβ mutation in the _Cbfb_f/f PLZF-Cre mice to validate our system. We observed highly efficient deletion of _Cbfb_ in the PLZF+ ILCP and ILC2

progenitors (ILC2Ps) from the bone marrow, ILC2s from the lung and small intestine, and ILC1s from the small intestine and partial _Cbfb_ deletion in NCR+ ILC3s from the small intestine in

the _Cbfb_f/f PLZF-Cre mice (Fig. 1c). However, the _Cbfb_ genes in the CD4+ T, CD8+ T, NK, and B cells were not greatly affected in the _Cbfb_f/f PLZF-Cre mice. Wild type _Cbfb_ transcripts

were efficiently deleted in the ILC subsets of the _Cbfb_f/f PLZF-Cre mice, although subtle transcript expression of mutated _Cbfb_ was detected in the non-ILC populations (Fig. 1d, e).

Thus, the Cbfβ dysfunction is specifically induced in ILC subsets among haematopoietic cell populations of the _Cbfb_f/f PLZF-Cre mice. The specificity of this deletion effect for ILC

subsets is surprising, because haematopoietic stem cells are fate-mapped by PLZF expression20. To confirm previous data, we crossed _Cbfb_f/f PLZF-Cre mice with Rosa26-tdTomato mice in which

PLZF-Cre expression in the progenitor cells could be followed by tdTomato expression in the _Cbfb_f/f PLZF-Cre mice. As previously described, most haematopoietic cells were labeled with

tdTomato in the mice (Supplementary Fig. 2). However, the _Cbfb_ gene locus flanked by loxps was quite intact in the tdTomato+ cells of the major haematopoietic cell populations. These data

indicate that PLZF-Cre can reach and excise the Rosa26 locus but not the _Cbfb_ locus in the progenitors of the major haematopoietic populations, probably due to the tight chromatin

structure of the _Cbfb_ locus. Next, we assessed the cell-intrinsic effect of Cbfβ deletion on the differentiation of PLZF+ ILCPs, ILC2Ps, and ILC2s in the lung and intestine by performing

competitive bone marrow reconstitution experiments. Fifty percent CD45.2+ _Cbfb_+/f PLZF-Cre or _Cbfb_f/f PLZF-Cre bone marrow cells were adoptively transferred together with fifty percent

CD45.1+ competitors into lethally irradiated CD45.1+ mice. The PLZF+ ILCPs, ILC2P, and ILC2s developed normally in the absence of Cbfβ function (Fig. 1f), although _Cbfb_f/f PLZF-Cre bone

marrow cells differentiated into fewer ILC1s and NCR+ ILC3s in the small intestine lamina propria lymphocytes (LPL) than _Cbfb_+/f PLZF-Cre bone marrow cells (Fig. 1g). Differentiation of

haematopoietic cells other than ILCs was not abrogated in the _Cbfb_f/f PLZF-Cre mice (Fig. 1g). Thus, Cbfβ is dispensable for differentiation of PLZF+ ILCPs and ILC2s in peripheral tissues.

RUNX RESTRAINS STEADY-STATE ILC2 ACTIVATION We investigated whether Cbfβ deficiency affected basal ILC2 activity in the steady state of the lung. To this end, first we examined KLRG1

activation marker expression on the ILC2s in the lung and intestine of the _Cbfb_+/f PLZF-Cre and _Cbfb_f/f PLZF-Cre mice21. ILC2s from the _Cbfb_f/f PLZF-Cre mice expressed more KLRG1 than

those from the _Cbfb_+/f PLZF-Cre mice (Fig. 2a). Further phenotypic analysis demonstrated that downregulation of Thy1 occurred on the _Cbfb_f/f PLZF-Cre ILC2s like ILC2s stimulated with

IL-2522. In addition, the _Cbfb_f/f PLZF-Cre ILC2s produced elevated levels of IL-5, which were correlated with enhanced recruitment of eosinophils to the bronchoalveolar space (Fig. 2b–d).

IL-25 stimulation induces inflammatory ILC2s defined as KLRG1Hi Thy1Lo ST2 (IL-33Ra)– ILC2s22. However, the _Cbfb_f/f PLZF-Cre ILC2s were different from these inflammatory ILC2s, because

expression of cytokine receptors, including ST2, was not significantly altered by Cbfβ deficiency (Supplementary Fig. 3). To investigate whether ILC2 activation in the _Cbfb_f/f PLZF-Cre

mice is cell intrinsic or extrinsic, we performed bone marrow competition assays with CD45.1+ competitor cells as described above. _Cbfb_f/f PLZF-Cre ILC2s in the recipient lungs showed

increased KLRG1 expression, decreased Thy1 expression, and IL-5 overproduction compared to those of the competitor cells (Fig. 2e). These data indicate that Cbfβ suppresses the basal

activity of ILC2s in a cell intrinsic manner. To address the question of which Runx proteins contribute to the ILC2 activation phenotype in the absence of Cbfβ, we sought to generate

_Runx1_f/f PLZF-Cre and _Runx3_f/f PLZF-Cre mice. However, most of the _Runx1_f/f PLZF-Cre mice died soon after birth for unknown reasons. Therefore, instead we generated _Cbfb_f/f ERT2-Cre,

_Runx1_f/f ERT2-Cre, _Runx3_f/f ERT2-Cre, and _Runx1_f/f _Runx3_f/f ERT2-Cre mice. Inducible deletion of Cbfβ or both Runx1 and Runx3 by oral tamoxifen administration led to a robust

reduction of Thy1 expression and an increase of IL-5 production in the intestine (Fig. 2f, g). On the other hand, single deletion of either Runx1 or Runx3 had little effect on Thy1

expression and IL-5 production by the ILC2s (Fig. 2f, g). These results suggest that Runx1 and Runx3 must work jointly and together with Cbfβ to repress ILC2 functions under steady-state

conditions. To investigate the physiological impact of enhanced ILC2 activity resulting from Cbfβ deficiency on the steady state of the lung, we adoptively transferred _Cbfb_f/f ILC2s or

_Cbfb_f/f ERT2-Cre ILC2s into _Rag2_–/– _Il2rg_–/– mice, which were treated with tamoxifen after transfer. At 3–4 weeks after the tamoxifen treatment, almost no damaged PAS+ epithelial cells

were observed in the lungs of the _Cbfb_f/f ERT2-Cre ILC2 recipient mice, although the _Cbfb_f/f ERT2-Cre ILC2s increased the eosinophil numbers in the bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid

(Fig. 2h, i). Thus, Cbfβ-deficient ILC2s are not sufficiently active to acutely damage lung epithelial cells but instead contribute to subsymptomatic eosinophil infiltration into the

bronchoalveolar space. RUNX ANTAGONIZES GATA-3 FUNCTION IN STEADY-STATE ILC2S A previous study demonstrated that Runx proteins antagonized GATA-3 function in T cells by directly binding to

GATA-323. We hypothesized that the same inhibitory mechanism by Runx proteins might function in ILC2s to suppress IL-5 production by antagonizing GATA-3 activity. To test this hypothesis, we

performed RNA sequence analysis of ILC2s from the lungs of _Cbfb_+/f PLZF-Cre and _Cbfb_f/f PLZF-Cre mice and analyzed the expression profiles of genes that were positively or negatively

regulated by GATA-3 in ILC2s24. If our hypothesis was correct, the function of GATA-3 as a transcription factor would be enhanced in the absence of Cbfβ. Deletion of Cbfβ in ILC2s led to

upregulation of 18 of 156 genes (11.5%) that were positively regulated by GATA-3 and downregulation of 30 of 151 genes (19.8%) that were negatively regulated by GATA-3 (Fig. 3a,

Supplementary Data 1). GATA-3 positively regulated IL-5 expression, and this effect was augmented by Cbfβ deficiency. In contrast, GATA3 was a negative regulator of Thy1 expression, which

was even more inhibited in the absence of Cbfβ. In addition, a set of genes positively or negatively regulated by GATA-3 was significantly enriched in the Cbfβ-deficient ILC2s (Fig. 3b).

Given that Runx/Cbfβ complexes antagonize GATA-3 function, over-expression of Runx protein should suppress IL-5 production by ILC2s. To explore this possibility, CD45.2+ C57BL/6 bone marrow

cells were transduced with a retroviral vector encoding Runx3, followed by IRES-Thy1.1 and were adoptively transferred into lethally irradiated CD45.1+ congenic mice. At 8 weeks after

transfer, the Thy1.1+ ILC2s over-expressing Runx3 produced less IL-5 than the Thy1.1– non-transduced cells or the Thy1.1+ cells transduced with the control vector (Fig. 3c, d). With the same

over-expression system, we confirmed that GATA-3 over-expression in ILC2s increased IL-5 production, which was inhibited by Runx3 (Supplementary Fig. 4). Collectively, the Runx/Cbfβ

complexes suppress the constitutive activity of ILC2s at least in part by inhibiting the function of GATA-3. RUNX PROTECTS ILC2S FROM EXHAUSTED-LIKE HYPORESPONSIVENESS To determine how Cbfβ

regulates ILC2 effector functions after activation, first we cultured ILC2s from the lungs of _Cbfb_+/f PLZF-Cre and _Cbfb_f/f PLZF-Cre mice with IL-2 and IL-33, which is a cytokine

combination that is the most potent ILC2 stimulator and is critical for establishment of allergic inflammation. We expected that this cytokine stimulation would lead to unleashed production

of TH2 cytokines by activated ILC2s due to Cbfβ deficiency. Surprisingly, ILC2s lacking Cbfβ secreted decreased IL-5 and IL-13 levels and did not grow well (Fig. 4a, b) in response to IL-2

and IL-33 in vitro. This hyporesponsiveness of ILC2s did not occur when the basal ILC2 activity was maintained by IL-2 and IL-7 without IL-33, which is a strong inducer of allergy (Fig. 4c).

To understand the mechanism of the low reactivity of Cbfβ-deficient ILC2s to IL-33, we conducted RNA sequencing analysis of in vitro-activated lung ILC2s from _Cbfb_+/f PLZF-Cre and

_Cbfb_f/f PLZF-Cre mice (Fig. 4d–i and Supplementary Data 2). The gene expression profiles of the transcription factors expressed in the ILC subsets were essentially comparable between the

_Cbfb_+/f PLZF-Cre and _Cbfb_f/f PLZF-Cre ILC2s with some exceptions, such as _Gfi1_, _Nfil3_, and _Irf8_ (Fig. 4e). However ablation of Cbfβ in the ILC2s led to reduced expression of many

effector cytokines and chemokines and their receptors. Surprisingly, crucial ILC2 cytokines, including _Il5_, _Il9_, _Il13_, _Csf2_ encoding GM-CSF, _Lta_, and _Areg_ encoding amphiregulin,

were all downregulated in ILC2s lacking Cbfβ (Fig. 4e, f). To remain activated, ILC2s require activating signals through cell surface receptors, including _IL7r_, _Il9r, IL4ra, Icos_, and

_Nmur1_, which all show reduced expression in the absence of Cbfβ (Fig. 4e, g). In contrast, Cbfβ-deficient ILC2s expressed high levels of T cell exhaustion markers, including the _Tnfrsf18_

encoding GITR, _Klrg1_, _Tigit_, _Prdm1_ encoding Blimp1, _Il10_, _Ctla4_, and _Lag3_ genes (Fig. 4e, h)14. Gene set enrichment analysis indicated that Cbfβ-deficient ILC2s stimulated with

IL-33 had a signature of exhausted CD8+ T cells (Fig. 4i). Since the TIGIT and IL-10 expression levels were low in the control ILC2s, we thought that upregulation of TIGIT and IL-10 might be

good marker for this hyporesponsiveness and confirmed the elevated expression of the IL-10 and TIGIT proteins in activated-ILC2s lacking Cbfβ in vitro (Fig. 4j, k). Collectively, ILC2s

present in the lungs of the _Cbfb_f/f PLZF-Cre mice show hyporesponsiveness to cytokine stimulation in vitro and acquire unique gene expression signatures similar to those observed in

exhausted T cells. IL-10 and inhibitory signals through TIGIT could be responsible for the low reactivity of the _Cbfb_f/f PLZF-Cre ILC2s against IL-33 stimulation. However, the IL-10

concentration in the culture supernatant of _Cbfb_f/f PLZF-Cre ILC2s was not high enough to detect the slight inhibitory effect on ILC2s (Supplementary Fig. 5a, b). Neutralization of IL-10

did not cancel the low reactivity of the _Cbfb_f/f PLZF-Cre ILC2s against IL-33 (Supplementary Fig. 5c). In addition, our RNA sequence analysis showed that the expression levels of TIGIT

ligands, such as CD112 and CD155, were quite low in ILC2s; the RPKM values of these molecules were less than 1. Therefore, the low reactivity of ILC2s without Cbfβ function did not result

from increased IL-10 or TIGIT expression. To determine what Runx proteins were responsible for this hyporesponsiveness to cytokine stimulation, we deleted Cbfβ, Runx1, Runx3, or both Runx1

and Runx3 by oral tamoxifen administration to _Cbfb_f/f ERT2-Cre, _Runx1_f/f ERT2-Cre, _Runx3_f/f ERT2-Cre, or _Runx1_f/f _Runx3_f/f ERT2-Cre mice as described above and stimulated the

intestinal ILC2s with IL-2 and IL-33 in vitro. Runx1 or Runx3 single deletion resulted in minor changes in IL-5 and IL-13 production by the ILC2s (Supplementary Fig. 6a, b). However, when

Runx1 and Runx3 were both deleted, IL-5 and IL-13 production were both reduced to the level observed in the Cbfβ-deleted ILC2s. In addition, we performed ChIP sequence analysis for Runx1 and

Runx3 binding in ILC2s activated with IL-33 to examine the differential functions of Runx1 and Runx3 in the hyporesponsiveness of ILC2s. However, generally the binding patterns were

comparable between Runx1 and Runx3 (Supplementary Fig. 6c, d). Collectively, both Runx1 and Runx3 serve as inhibitors of the exhausted-like phenomenon in cooperation with Cbfβ.

GATA-3-DEPENDENT AND GATA-3-INDEPENDENT FUNCTIONS OF RUNX IN ILC2S We sought to investigate how pre-activated _Cbfb_f/f PLZF-Cre ILC2s at steady state showed hyporesponsiveness to IL-33

stimulation. First, we hypothesized that GATA-3 overactivation due to the absence of antagonizing effects by the Runx protein pushed ILC2s into an overactivated hypofunctional state.

However, over-expressed GATA-3 still enhanced IL-5 and IL-13 production by ILC2s in response to IL-33 in vitro (Fig. 5a, b). To examine whether the Runx proteins inhibited ILC2 activity by

antagonizing GATA-3 as observed in the steady-state ILC2s, we evaluated cytokine production by IL-33-stimulated ILC2s over-expressing Runx3. Interestingly, Runx3 over-expression dampened

cytokine production by ILC2s in response to IL-33. Thus, the Runx proteins apparently inhibit ILC2 activity in a dose-dependent manner even after IL-33 stimulation. Since high transcription

factor expression is not always required for enhancer or repressor function, we hypothesize that a dose-independent and GATA-3-independent function of Runx proteins should exist as an

epigenetic modulator for ILC2s to normally respond to IL-33. To test this possibility, we examined Cbfβ binding in ILC2s cultured with or without IL-33 by ChIP sequence analysis and found

that new Cbfβ binding peaks appeared in ILC2s cultured with IL-33 (Fig. 5c). The GATA-3 motif was not ranked in at least the top ten motifs of the Cbfβ binding peaks specific for ILC2s

stimulated with IL-33 (Fig. 5d). Furthermore, the IL-33-specific Cbfβ binding peaks were located at genes for ILC2 function, including _Il5_, _Il13_, _Lta_, _Nmur1_, and _Vipr2_, and genes

for exhaustion markers, including _Il10_, _Tigit_, _Prdm1_, _Lag3_, and _Ctla4_ (Fig. 5e). Examples of these GATA-3-independent Cbfβ biding peaks are shown in Fig. 6a. Thus, Cbfβ binding

specific to IL-33 stimulation is independent of GATA-3 and is associated with a gene expression profile of exhausted-like ILC2s, suggesting a GATA-3-independent function of the Runx proteins

in ILC2 reactivity against IL-33. ENHANCER OR REPRESSOR FUNCTIONS OF RUNX IN ACTIVATED ILC2S We assessed the possibility that Runx/Cbfβ complexes bound to enhancers of gene loci related to

ILC2 activity and repressors of exhaustion marker gene loci in ILC2s stimulated with IL-33. For this purpose, we determined which Cbfb binding peaks were marked by H3K27 acetylation for

enhancer regions or H3K27 trimethylation for repressed gene regions in ILC2s stimulated with IL-33 (Fig. 6a, b and Supplementary Data 2). Cbfβ binding peaks overlapping with H3K27

acetylation peaks were associated with ILC2 functional genes that were downregulated in the hyporesponsive Cbfβ-deficient ILC2s (Fig. 4e). Gene ontology analysis of the genes with both Cbfβ

and H3K27 acetylation peaks indicated that Cbfβ globally regulated genes involved in positive regulation of proliferation, cytokine production, cytokine-mediated signaling, leukocyte

migration, and leukocyte adhesion (Fig. 6c). In contrast, the H3K27 trimethylation status of the exhaustion marker genes was variable. Among the genes listed as exhaustion markers in Fig.

4h, H3K27 trimethylation was observed in the _Il10_, _Prdm1_, and _Ctla4_ loci. Since IL-10 is a good marker for exhausted-like ILC2s, we confirmed the reduced H3K27 trimethylation level in

the _Il10_ promoter region of _Cbfb_f/f PLZF-Cre ILC2s activated by IL-33, indicating that the _Il10_ locus was repressed by Runx proteins in part through H3K27 trimethylation (Fig. 6d).

Collectively, Runx/Cbfβ complexes have comprehensive effects as transcription factors on the gene expression profile of exhausted-like ILC2s. RUNX DEFICIENCY IN ILC2S AMELIORATES ALLERGIC

INFLAMMATION ILC210s can be found in vivo during chronic or severe inflammation12. To identify TIGIT+ IL-10+ ILC2s in physiological settings, we took advantage of a severe subacute asthma

model with IL-10-Venus reporter mice administered a high dose of papain every three days. On day 7 after administration of three papain doses, ILC2s producing IL-10 were observed in the BAL

fluid and lung (Fig. 7a, b). However, TIGIT+IL-10+ ILC2s were found only in the BAL fluid, which was the site of severe inflammation, but not in the lung. Since most TIGIT+ ILC2s expressed

IL-10-Venus, TIGIT+ ILC2s can represent TIGIT+IL-10+ ILC2s. The TIGIT+ ILC2s in the BAL fluid are a small population of activated ILC2s that are marked by PD-1, GITR, and KLRG1

expression15,25 and are not inflammatory ILC2s due to normal ST2 expression (Fig. 7c)22. TIGIT+ ILC2s did not proliferate well, as determined by diminished Ki67 staining and were negative

for a dead cell marker (Fig. 7d, e). The RT-PCR assay indicated lower _Il5_ and _Il13_ expression in the TIGIT+ ILC2s than in the TIGIT– ILC2s. The hyporesponsive TIGIT+ ILC2s emerged in the

lung, as well as in the BAL fluid, when the mice were treated with papain every three days for a month (Supplementary Fig. 7a). Furthermore, to examine whether the TIGIT+IL-10+ ILC2s in the

BAL fluid were similar to the hyporesponsive Cbfβ-deficient ILC2s, we performed RNA sequence analysis by barcoding individual cDNA molecules from one hundred TIGIT+ and TIGIT– ILC2s. The

sample number (_n_ = 3) and assay sensitivity were not sufficient to observe a significant reduction of _Il5_ and _Il13_ expression in the TIGIT+ ILC2s, although the _Il5_ and _Il13_

transcript levels were significantly decreased in the TIGIT+ ILC2s based on a sensitive RT-PCR analysis (Fig. 7f, Supplementary Fig. 8, and Supplementary Data 3). Despite these limitations,

the gene set enrichment analysis showed that the signature genes of TIGIT+ ILC2s in the BAL fluid were enriched in the low-reactive Cbfβ-deficient ILC2s. Thus, severe allergy induced

hyporesponsive TIGIT+ IL-10+ ILC2s similar to Cbfβ-deficient ILC2s. To investigate the impact of increased exhausted-like ILC2s resulting from Cbfβ deficiency on inflammation, we created a

subacute asthma model with a high dose of papain using congenic mice adoptively transferred with bone marrow cells from either _Cbfb_+/f PLZF-Cre or _Cbfb_f/f PLZF-Cre mice. As expected, the

recipients of the _Cbfb_f/f PLZF-Cre bone marrow cells had reduced eosinophils and ILC2s in the BAL fluid and lungs (Fig. 8a), which were accompanied by a reduction in IL-5 and IL-13

production in the BAL fluid (Fig. 8b), as well as less immune cell infiltration around the bronchi (Fig. 8c, d) than those of the _Cbfb_+/f PLZF-Cre cell recipients. Furthermore, ILC2s

without Cbfβ function in the lung generated an increased TIGIT+ fraction and produced less IL-5 and IL-13 but more IL-10 than the control ILC2s (Fig. 8e–g). However, the increased IL-10 from

the Cbfβ-deficient ILC2s did not seem to be responsible for the reduced allergic inflammation, because the IL-10 concentration of the BAL fluid was not increased in the papain-treated

recipients of the _Cbfb_f/f PLZF-Cre bone marrow cells, probably due to higher IL-10 production by lineage+ cells than by ILC2s (Figs. 7a, 8b). Cell-intrinsic hyporeactivity of _Cbfb_f/f

PLZF-Cre ILC2s was also confirmed by bone marrow competition (Fig. 8h). Thus, the exhausted-like phenomenon in ILC2s was associated with decreased inflammation mediated by eosinophils. To

determine the function of Cbfβ-deficient ILC2s in the chronic allergy model, mice were continuously administered a high dose of papain every three days for one month as a severe chronic

allergy model (Supplementary Fig. 7c) or a high dose of papain every three days three times followed by the same course of papain treatment after a two week cessation period as a repeated

chronic allergy model (Supplementary Fig. 7d). Cbfβ-deficient ILC2s did not respond well to papain stimulation in the model mice. However, the hyporesponsive _Cbfb_f/f PLZF-Cre ILC2s were

associated with reduced eosinophil recruitment only after a 2nd course of papain challenge. Thus, Runx/Cbfβ complexes in ILC2s play a critical role in inflammatory responses to repeated

allergen stimulation. To further determine the effect of Cbfβ deficiency in ILC2s on allergic inflammation, we adoptively transferred Cbfβ-deficient ILC2s prepared by Cbfβ deletion during in

vitro culture of lung ILC2s into _Rag2_–/– _Il2rg_–/– mice lacking both acquired immunity and innate lymphoid cells. Prior to the adoptive transfer, we confirmed acquisition of an

exhausted-like phenotype including high IL-10 and TIGIT expression with low IL-5 and IL-13 production due to Cre-mediated conversion of the floxed allele (Fig. 9a, b). The _Rag2_–/–

_Il2rg_–/– recipients were intranasally administered papain for 3 consecutive days. Analysis of these mice on day 3 revealed that the transferred Cbfβ-deficient ILC2s were less capable of

recruiting eosinophils to the bronchoalveolar space and the lung (Fig. 9c), with a decreased amount of IL-5 in the BAL fluid and increased epithelial damage (Fig. 9d–f). These data indicate

that Cbfβ is required for the ability of ILC2s to trigger and extend allergic inflammation and to prevent them from falling into an exhausted-like state in inflamed tissues. DISCUSSION We

have shown here that Runx/Cbfβ complexes suppress the basal activity of ILC2s, which can recruit eosinophils through IL-5 production under steady-state conditions. However, under allergic

conditions, Runx/Cbfβ complexes support the ability of ILC2s to exert their helper functions for type 2 immunity. Diminished activity of ILC2s lacking Runx under allergic inflammatory

conditions was accompanied by increased expression of T cell exhaustion markers, such as IL-10 and TIGIT. Mechanistically, Runx/Cbfβ complexes contribute to epigenetic modification for a

gene expression profile of the exhausted-like ILC2s. These TIGIT+ IL-10+ ILC2s were identified even in mice with allergen-induced subacute or chronic inflammation. Finally, transferred ILC2s

with exhausted-like characteristics lacked an appropriate capacity for allergic immune responses in vivo. Thus, our results revealed an essential regulation of ILC2 function by Runx

proteins and an accelerated emergence of exhausted-like ILC2s in the absence of Runx/Cbfb complexes. We used PLZF-Cre mice to induce dysfunction of Cbfβ in ILC2s. We obtained a Cbfβ deletion

that was rather specific to ILC subsets in _Cbfb_f/f PLZF-Cre mice, although PLZF-Cre is expressed in unknown progenitor cells for most haematopoietic cells. We cannot completely deny the

possibility that any small population of haematopoietic cells may be affected in the _Cbfb_f/f PLZF-Cre mice. Therefore, using PLZF-Cre mice for an ILC study is quite risky and requires

precise examination of the deletion effect on the haematopoietic populations, as described in our paper. Since both TIGIT and IL-10 are induced by IL-3312, a strong IL-33 signal should be

required for the generation of TIGIT+ IL-10+ ILC2s. The hyporesponsive TIGIT+ IL-10+ ILC2s are apparently part of the activated ILC2s, because they express a series of activation markers,

including PD-1 and KLRG1, which are also known inhibitory molecules. T cells become exhausted through interaction of their inhibitory receptors, such as CTLA-4 and PD-1, with cognate ligands

on other cells14. Therefore, we can reasonably assume that the low reactivity of TIGIT+ IL-10+ ILC2s results from accumulated signals through those inhibitory molecules. Although we did not

test the function of the individual inhibitory molecules on the TIGIT+ IL-10+ ILC2s, we clearly showed that the emergence of hyporeactive TIGIT+ IL-10+ ILC2s was negatively regulated by

Runx/Cbfβ complexes. Chronic or severe inflammation is required to induce TIGIT+ IL-10+ ILC2s. If ILC2s have functional Runx proteins, then hyporesponsive TIGIT+ IL-10+ ILC2s are rare even

after continuous inhalation of papain for one month. Furthermore, _Cbfb_f/f PLZF-Cre ILC2s with low reactivity were not associated with attenuation of chronic allergy. These data indicate

that TIGIT+ IL-10+ ILC2s and ILC2s themselves play a limited role in the pathology of chronic inflammation. However, hyporesponsive ILC2s lacking Cbfβ protect the host from exaggerated

allergic inflammation when repeatedly treated with allergen. Therefore, regulation of ILC2 functions by Runx/Cbfb complexes is critical for the pathogenesis of acute exacerbation of chronic

allergy. ILC210s are identified by low _Tnf_, _Lta_, _Il2_, _Retnla_, and _Ccl1_ expression and high _Il10_ and _Id3_ expression compared to the expression levels of the non-IL-10

producers12. Cbfβ-deficient ILC2s are somewhat similar to ILC210s in that _Tnf_, _Lta, Retnla_ and _Ccl1_ expression is reduced in both cell types and IL-10 production is increased. However,

Cbfβ ablation resulted in more global defects in ILC2 function, because ILC2s lacking Cbfβ poorly expressed the main effector cytokines, such as _Il5_ and _Il13_, whereas ILC210s produce

large amounts of IL-5 and IL-1312. Furthermore, the expression of T cell exhaustion markers is not increased on ILC210s, whereas the high _Id3_ expression observed in ILC210s is not induced

in Cbfβ-deficient ILC2s. Thus, the hyporesponsive ILC2s lacking Cbfβ seem to be different from ILC210s. Immunosenescence is another hyporesponsive state of immune cells that results from the

effects of ageing. Cell cycle arrest related to telomere shortening or DNA damage is thought to be a common feature of cellular senescence26. Runx1 is involved in age-related changes in

haematopoietic stem cells27. The regenerative capacity of HSCs declines following conditional ablation of Runx1 after an initial expansion28. In our study, we utilized a subacute or repeated

allergy model to induce ILC2 hyporesponsiveness. Testing whether aging could be a trigger for senescent ILC2s and whether the absence of Runx function was involved in ILC2 senescence would

be fascinating. The concept of exhausted-like ILC2s provides a better understanding of normal ILC2 physiology. Many mouse models have successfully demonstrated the importance of ILC2s during

the acute phase of an allergic response29. In addition, an important role of ILC2s in worsening of recurrent allergy has been suggested. ILC2s can also be trained by the initial allergic

stimulation, resulting in production of higher TH2 cytokine levels after a second challenge13. The immune system always has delicate balancing mechanisms to maintain homeostasis.

Exhausted-like hyporesponsiveness is one mechanism by which immune cells are prevented from overactivation and continuous production of harmful inflammatory cytokines. Therefore, ILC2s may

possess a capacity to reduce their activity similar to that of exhausted T cells after chronic exposure to allergic stimuli. The frequency and activity of ILC2s are both increased in

patients with chronic type 2 inflammation, including asthma and atopic dermatitis and are also associated with the disease severity30,31,32. Given a possible role of chronic inflammation in

tissues in providing environmental cues to induce low reactive ILC2s, an examination of whether hyporesponsive ILC2s are present in and beneficial for patients with chronic allergy will be

important, especially in cases of acute disease exacerbation. Our study in mice revealed that attenuated Runx function accelerated the differentiation of ILC2s towards a hyporesponsive

state. Further understanding of the molecular switch triggering exhausted-like ILC2s may provide a basis for the development of therapeutic targets to suppress allergic immune responses.

METHODS MICE All mice were maintained at the RIKEN Center for Integrative Medical Sciences. The animal protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of RIKEN

Yokohama Branch. C57BL/6 mice and congenic CD45.1+ mice were obtained from the National Cancer Institute. IL-10-Venus reporter mice were kindly provided by Dr Kiyoshi Takeda at Osaka

University. The _Cbfb_f/f (Stock No. 008765), _Runx1_f/f (Stock No. 008772), _Runx3_f/f (Stock No. 008773), PLZF-Cre (Stock No. 024529), and ERT2-Cre mice (Stock No. 008463) were all

obtained from Jackson Laboratories. All Cre-expressing mice were heterozygous. CELL PREPARATION Cells were isolated from the spleen, liver, BAL fluid, lung, and small intestine as previously

reported17. The spleen and liver were dissected and smashed through a 70 µm strainer. Lymphocytes from the liver were resuspended in 40% Percoll and centrifuged at 2000 rpm at room

temperature for 20 min. Cells at the bottom of the tube were collected for flow cytometry after red blood cell (RBC) lysis. BAL fluid was obtained by infusion of PBS through a catheter. The

dissected lung was cut into small pieces, chopped with a razor blade, and incubated in 8 mL of digestion buffer containing RPMI medium with 2% FBS, 0.5 mg per mL of Collagenase IV (Sigma,

C5138), and 0.05 mg per mL of DNase (Wako, 043-26773) at 200 rpm and 37 °C for 45 min. Digested cells were smashed through a 70 µm strainer and used for flow cytometry and cell culture after

RBC lysis. Lung lymphocytes were further purified with a 40 and 80% Percoll gradient for sorting. Intraepithelial lymphocytes (IELs) and LPLs were isolated from the small intestine. After

removing feces and Peyer’s patches, the small intestine was incubated in 20 mL of RPMI medium with 2% FBS and 5 mM EDTA at 200 rpm and 37 °C for 20 min. After vigorous vortexing, floating

cells were collected as the IELs. The remaining tissues were cut into small pieces, chopped with a razor blade, and incubated in 20 mL of the same digestion buffer at 200 rpm and 37 °C for

30 min. Digested cells containing LPLs or the IELs collected above were purified with a 40 and 80% Percoll gradient for flow cytometry, culture and sorting. Lymphocytes from the lung and

intestine were cultured with GoldiPlug without any stimulation to assess ex vivo production of IL-5 and IL-13 or with PMA (50 ng per mL) and Ionomycin (0.5 µg per mL) to analyze cytokine

production by ILC2s from mice treated with papain for 4 h. ILC2s were sorted from the lung with the FACSAria (BD Biosciences). Five hundred ILC2s were cultured with IL-2 (10 ng per mL),

IL-33 (10 ng per mL), and with/without IL-7 (10 ng per mL). For inducible deletion of _Cbfb_, 1 µM of 4-hydroxytamoxifen (4OHT) was added to the cell culture for 4 days. ANTIBODIES AND FLOW

CYTOMETRY Cells were blocked with an anti-CD16/32 antibody (2.4g2) first and then stained with Fixable Viability Dye eFluor 506 (eBioscience) for detection of dead cells before staining the

cell surfaces. The antibodies used for flow cytometry are all listed in Supplementary Table 1. The Cytofix/Cytoperm Buffer Set (BD Biosciences) and Foxp3/Transcription Factor Staining Buffer

Set (eBioscience) were used for staining of intracellular cytokines and transcription factors, respectively, according to the manufacturers’ protocols. Data were acquired on a FACSCanto II

(BD Biosciences) and analyzed with the FlowJo software (TreeStar). Gating and sorting strategies were described in Supplementary Fig. 9. PCR AND RT-PCR Cells were directly sorted into DNA

extraction buffer (0.1 M Tris-HCL pH 7.5, 0.05 M EDTA pH 8.0, and 1.25% SDS) for DNA or TRIzol (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for RNA by the FACSAria. DNA was purified from the cell lysates with

Phenol-Chloroform Isoamyl Alcohol, followed by ethanol precipitation. RNA was purified, and cDNA was synthesized with the PrimeScript™ 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Takara) following the

manufacturer’s protocol. Then, the mRNA transcripts were quantified with TB Green™ Premix Ex Taq™ II (Takara). The relative expression of the indicated transcripts was calculated by the

2−ΔCt method and normalized to _Actb_ expression. The copy numbers of _Cbfb_ transcripts with or without a floxed region were calculated by quantitative RT-PCR. The specific primers are

listed in Supplementary Table 2. BONE MARROW COMPETITION Recipient CD45.1+ or CD45.1+/CD45.2+ congenic mice were lethally irradiated at 950 rad and reconstituted with 5 × 106 bone marrow

cells from _Cbfb_+/f PLZF-Cre (CD45.2+) mice or 5 × 106 CD45.1+ bone marrow cells from _Cbfb_f/f PLZF-Cre (CD45.2+) mice. At 8–12 weeks after transfer, the presence of the indicated cells

was analyzed in the spleen, bone marrow, lung, liver, and small intestine. PAPAIN-INDUCED ASTHMA MODEL After irradiation at 950 rad, CD45.1+ congenic mice were transferred with 1 × 107 bone

marrow cells from either _Cbfb_+/f PLZF-Cre or _Cbfb_f/f PLZF-Cre mice. At 12 weeks after transfer, 100 µg of papain in 50 µL of sterile PBS was intranasally administered to the recipient

mice every 3 days. On day 7 or 14, a 20-G catheter was inserted into the trachea, and 1 mL of PBS was infused into the lung through the catheter and aspirated 3 times. The first BAL fluid

sample was used to detect IL-5, IL-10, and IL-13 by ELISA. Cells in the whole BAL fluid were analyzed by flow cytometry. After making a knot at the left main bronchus, the left lung was

removed to isolate cells for flow cytometry. The right lung was intratracheally infused with 1 mL of 10% formalin, removed, and incubated in 10% formalin at 4 °C overnight to make paraffin

blocks. HE and PAS staining were performed as previously reported17. To expand ILC2s from the lungs of the _Cbfb_f/f and _Cbfb_f/f ERT2-Cre mice, ILC2s were cultured in RPMI medium with 10%

FBS, 55 µM 2ME, 1% Pen Strep, 10 ng per mL of IL-2 (Peprotech), and 10 ng per mL of IL-7 (Peprotech) for 2–4 weeks. For adoptive transfer of _Cbfb_f/f or _Cbfb_f/f ERT2-Cre ILC2s without in

vitro tamoxifen treatment into _Rag2_–/– _Il2rg_–/– mice, 1 × 106 cells were intravenously injected, and the mice were treated with tamoxifen as described below. To delete _Cbfb_ and

stimulate ILC2s in vitro, 1 µM of 4-hydroxytamoxifen (4OHT) was added to the culture with 10 ng per mL of IL-33. At day 4 after 4OHT treatment, 4OHT was removed from the cell culture. At day

7 after 4OHT treatment, the ILC2s were collected and injected into _Rag2_–/– _Il2rg_–/– mice (1 × 106 cells/mouse). Then, 100 µg of papain in 50 µL of PBS was intranasally administered to

the _Rag2_–/– _Il2rg_–/– mice on days 0, 1, and 2. On day 3, the BAL fluid and lung were collected as described above. HISTOLOGY SCORE Lung injury was scored as previously described33.

Briefly, scores were given as follows: grade 1, a few inflammatory cells around the bronchus; grade 2, a layer one cell deep around the bronchus; grade 3, a layer two to four cells deep

around the bronchus; and grade 4, a layer of more than four cells deep surrounded the bronchus. Six airways per section were randomly selected for scoring. PAS-positive lung epithelial cells

were counted at a magnification of ×400 when at least one clear PAS-positive cell was found. INDUCIBLE DELETION OF CBFΒ, RUNX1 AND RUNX3 IN VIVO _Cbfb_f/f ERT2-Cre, _Runx1_f/f ERT2-Cre,

_Runx3_f/f ERT2-Cre, _Runx1_f/f _Runx3_f/f ERT2-Cre, and _Rag2_–/– _Il2rg_–/– recipient mice transferred with _Cbfb_f/f or _Cbfb_f/f ERT2-Cre ILC2s were orally administered 4 mg of tamoxifen

(Sigma) in 200 µL of corn oil (Wako) for 5 consecutive days. At 3-4 weeks after tamoxifen treatment, ILC2s were isolated from the small intestine LPLs for flow cytometry and short-term

culture to analyze ex vivo IL-5 production as described above. Eosinophils in the BAL fluid and PAS-positive lung epithelial cells of the _Rag2_–/– _Il2rg_–/– recipient mice were analyzed by

flow cytometry and histology, respectively. RNA SEQUENCING RNA was extracted from ILC2s sorted from the lungs of _Cbfb_+/f PLZF-Cre or _Cbfb_f/f PLZF-Cre mice and from lung ILC2s cultured

with 10 ng per mL of IL-2 and 10 ng per mL of IL-33 in vitro for 4 days using TRIzol (Qiagen), followed by the RNeasy micro kit (Qiagen). Sequencing libraries were prepared with a SMARTer

Pico kit (Clontech). Single end 50 bp reads were obtained by an Illumina HiSeq 1500. The reads were mapped and analyzed with TopHat v2.1.0 and Cufflinks 2.2.1. Heat maps were generated from

the z-score by Morpheus (Broad Institute). Gene set ontology analysis (Broad Institute) was performed with a gene set that was positively or negatively regulated by GATA-3 and gene

expression data (RPKM) from the _Cbfb_+/f PLZF-Cre and _Cbfb_f/f PLZF-Cre ILC2s; a gene set for a CD8+ T cell exhaustion signature was previously described34, and gene expression data were

obtained from the _Cbfb_+/f PLZF-Cre and _Cbfb_f/f PLZF-Cre ILC2s. EdgeR was used to calculate differentially expressed genes and draw the MA plot. CHROMATIN IMMUNOPRECIPITATION SEQUENCING

ILC2s were sorted from the lungs of C57BL/6 mice and expanded in vitro in RPMI medium with 10% FBS, 55 µM 2ME, 1% Pen Strep, 10 ng per mL of IL-2 (Peprotech), 10 ng per mL of IL-7

(Peprotech), and 10 ng per mL of IL-33 (Peprotech) for 4 weeks to expand the cells. Then, the ILC2s were cultured with or without IL-33 for 1–2 weeks, and 1.5 × 107 ILC2s were collected per

ChIP-seq sample. For ChIP followed by qPCR, lung ILC2s from _Cbfb_+/f PLZF-Cre and _Cbfb_f/f PLZF-Cre mice were cultured with IL-2 and IL-7 for 3 weeks and stimulated with IL-2, IL-7, and

IL-33 for one week. We followed the ChIP-seq protocol described elsewhere17,35. Briefly, after 10 min of fixation in 1% paraformaldehyde at room temperature, the reaction was stopped by a

glycine solution (final concentration of 0.15 M), and the cells were lysed in lysis buffer 1 (50 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 140 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol, 0.5% NP40, and 0.25% Triton X-100)

with cOmplete protease inhibitor cocktail tablets (Roche). The nuclei were pelleted and then washed with lysis buffer 2 (10 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 200 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA and 0.5 mM EGTA) with

the cOmplete protease inhibitor. The nuclei were resuspended in lysis buffer 3 (10 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM EGTA, 0.1% sodium deoxycholate and 0.5%

N-laurylsarcosine sodium salt) and sonicated using the model XL2000 ultrasonic cell disruptor (MICROSON). The fragmented chromatin was immunoprecipitated with an anti-Cbfβ36, anti-H3K27

acetylation (D5E4, Cell Signaling), anti-H3K27 trimethylation (ab6002, Abcam), anti-GATA-3 (L50-823, BD), anti-Runx1 (ab23980, Abcam), or anti-Runx3 (D6E2, Cell Signaling) antibody. After

reverse cross-linking and purification steps, the ChIP’d DNA was re-sonicated with the Covaris S220. Libraries were created from the DNA with the NEBNext ChIP-seq Library Prep Master Mix set

for Illumina kit (NEB) and sequenced with the Illumina HiSeq 1500. The sequences were mapped to the mouse genome using Bowtie 2. The peaks were called with the MACS2 programme or HOMER with

default parameters. Visualization of binding traces and motif analysis were performed by HOMER. Differential binding of Cbfβ in ILC2s cultured with IL-2/IL-7/IL-33 and with IL-2/IL-7 was

calculated by ChIPpeakAnno and HOMER. ChIPpeakAnno and HOMER were used to annotate genes with Cbfβ binding unique to IL-2/IL-7/IL-33 stimulation. ChIPpeakAnno was also used to annotate genes

with Cbfb binding peaks marked by H3K27 acetylation near their coding regions. GO enrichment analysis was performed with 200 genes (logFC>1.5 and logCPM>2) using ClusterPlofiler.

RETROVIRAL TRANSDUCTION C57BL/6 bone marrow cells were transduced with a pMSCV-Thy1.1 retroviral vector encoding Runx3 as described elsewhere37. Lung ILC2s were cultured with 10 ng per mL of

IL-2, 10 ng per mL of IL-7, and 10 ng per mL of IL-33 in vitro. The ILC2s were transduced with a pMSCV-IRES-Thy1.1 with either GATA-3 or Runx3 and then cultured for another week. GoldiPlug

was added for the last four hours, and IL-5 and IL-13 production by the transduced or untransduced cells was analyzed by flow cytometry. STATISTICAL ANALYSIS Data were analyzed by the

two-tailed Student’s _t_-test with or without Welch’s correction. _P_ values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. REPORTING SUMMARY Further information on experimental design

is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article. DATA AVAILABILITY RNA sequence and ChIP sequence data have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus at

NCBI under primary accession code GSE111871. All other data are available from the authors upon reasonable requests. CHANGE HISTORY * _ 01 MARCH 2019 The original version of this Article

contained an error in the author affiliations. Affiliation 5 incorrectly read ‘Laboratory for Prediction of Cell Systems Dynamics, RIKEN Center for Biosystems Dynamics Research (BDR), Suite,

Hyogo 565-0874, Japan.’ This has now been corrected in both the PDF and HTML versions of the Article. _ REFERENCES * Sonnenberg, G. F. & Artis, D. Innate lymphoid cells in the

initiation, regulation and resolution of inflammation. _Nat. Med._ 21, 698–708 (2015). Article CAS Google Scholar * Moro, K. et al. Innate production of T(H)2 cytokines by adipose

tissue-associated c-Kit(+)Sca-1(+) lymphoid cells. _Nature_ 463, 540–544 (2010). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Halim, T. Y., Krauss, R. H., Sun, A. C. & Takei, F. Lung natural

helper cells are a critical source of Th2 cell-type cytokines in protease allergen-induced airway inflammation. _Immunity_ 36, 451–463 (2012). Article CAS Google Scholar * Klose, C. S. et

al. Differentiation of type 1 ILCs from a common progenitor to all helper-like innate lymphoid cell lineages. _Cell_ 157, 340–356 (2014). Article CAS Google Scholar * Neill, D. R. et al.

Nuocytes represent a new innate effector leukocyte that mediates type-2 immunity. _Nature_ 464, 1367–1370 (2010). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Sonnenberg, G. F., Monticelli, L. A.,

Elloso, M. M., Fouser, L. A. & Artis, D. CD4(+) lymphoid tissue-inducer cells promote innate immunity in the gut. _Immunity_ 34, 122–134 (2011). Article CAS Google Scholar * Wang, S.

et al. Regulatory innate lymphoid cells control innate intestinal inflammation. _Cell_ 171, 201–216 (2017). e218. Article CAS Google Scholar * Nussbaum, J. C. et al. Type 2 innate

lymphoid cells control eosinophil homeostasis. _Nature_ 502, 245–248 (2013). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Wallrapp, A. et al. The neuropeptide NMU amplifies ILC2-driven allergic lung

inflammation. _Nature_ 549, 351–356 (2017). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Cardoso, V. et al. Neuronal regulation of type 2 innate lymphoid cells via neuromedin U. _Nature_ 549,

277–281 (2017). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Klose, C. S. N. et al. The neuropeptide neuromedin U stimulates innate lymphoid cells and type 2 inflammation. _Nature_ 549, 282–286

(2017). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Seehus, C. R. et al. Alternative activation generates IL-10 producing type 2 innate lymphoid cells. _Nat. Commun._ 8, 1900 (2017). Article ADS

Google Scholar * Martinez-Gonzalez, I. et al. Allergen-experienced Group 2 innate lymphoid cells acquire memory-like properties and enhance allergic lung inflammation. _Immunity_ 45,

198–208 (2016). Article CAS Google Scholar * Wherry, E. J. & Kurachi, M. Molecular and cellular insights into T cell exhaustion. _Nat. Rev. Immunol._ 15, 486–499 (2015). Article CAS

Google Scholar * Taylor, S. et al. PD-1 regulates KLRG1(+) group 2 innate lymphoid cells. _J. Exp. Med_ 214, 1663–1678 (2017). Article CAS Google Scholar * Collins, A., Littman, D. R.

& Taniuchi, I. RUNX proteins in transcription factor networks that regulate T-cell lineage choice. _Nat. Rev. Immunol._ 9, 106–115 (2009). Article CAS Google Scholar * Ebihara, T. et

al. Runx3 specifies lineage commitment of innate lymphoid cells. _Nat. Immunol._ 16, 1124–1133 (2015). Article CAS Google Scholar * Draper, J. E. et al. A novel prospective isolation of

murine fetal liver progenitors to study in utero hematopoietic defects. _PLoS Genet._ 14, e1007127 (2018). Article Google Scholar * Liu, T. M. & Lee, E. H. Transcriptional regulatory

cascades in Runx2-dependent bone development. _Tissue Eng. Part B Rev._ 19, 254–263 (2013). Article Google Scholar * Constantinides, M. G., McDonald, B. D., Verhoef, P. A. & Bendelac,

A. A committed precursor to innate lymphoid cells. _Nature_ 508, 397–401 (2014). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Hoyler, T. et al. The transcription factor GATA-3 controls cell fate and

maintenance of type 2 innate lymphoid cells. _Immunity_ 37, 634–648 (2012). Article CAS Google Scholar * Huang, Y. et al. IL-25-responsive, lineage-negative KLRG1(hi) cells are

multipotential ‘inflammatory’ type 2 innate lymphoid cells. _Nat. Immunol._ 16, 161–169 (2015). Article CAS Google Scholar * Yagi, R. et al. The transcription factor GATA3 actively

represses RUNX3 protein-regulated production of interferon-gamma. _Immunity_ 32, 507–517 (2010). Article CAS Google Scholar * Yagi, R. et al. The transcription factor GATA3 is critical

for the development of all IL-7Ralpha-expressing innate lymphoid cells. _Immunity_ 40, 378–388 (2014). Article CAS Google Scholar * Nagashima, H. et al. GITR cosignal in ILC2s controls

allergic lung inflammation. _J. Allergy Clin. Immunol._ 141, 1939–1943 (2018). e1938. Article CAS Google Scholar * Crespo, J., Sun, H., Welling, T. H., Tian, Z. & Zou, W. T cell

anergy, exhaustion, senescence, and stemness in the tumor microenvironment. _Curr. Opin. Immunol._ 25, 214–221 (2013). Article CAS Google Scholar * Wang, Q. et al. The CBFbeta subunit is

essential for CBFalpha2 (AML1) function in vivo. _Cell_ 87, 697–708 (1996). Article CAS Google Scholar * Jacob, B. et al. Stem cell exhaustion due to Runx1 deficiency is prevented by Evi5

activation in leukemogenesis. _Blood_ 115, 1610–1620 (2010). Article CAS Google Scholar * Halim, T. Y. Group 2 innate lymphoid cells in disease. _Int. Immunol._ 28, 13–22 (2016). CAS

Google Scholar * Salimi, M. et al. A role for IL-25 and IL-33-driven type-2 innate lymphoid cells in atopic dermatitis. _J. Exp. Med._ 210, 2939–2950 (2013). Article CAS Google Scholar *

Palikhe, N. S. et al. Elevated levels of circulating CD4(+) CRTh2(+) T cells characterize severe asthma. _Clin. Exp. Allergy_ 46, 825–836 (2016). Article CAS Google Scholar * Peebles, R.

S. Jr. At the bedside: the emergence of group 2 innate lymphoid cells in human disease. _J. Leukoc. Biol._ 97, 469–475 (2015). Article CAS Google Scholar * Tamaru, S. et al. Deficiency

of phospholipase A2 receptor exacerbates ovalbumin-induced lung inflammation. _J. Immunol._ 191, 1021–1028 (2013). Article CAS Google Scholar * Man, K. et al. Transcription factor IRF4

promotes CD8(+) T Cell exhaustion and limits the development of memory-like T cells during chronic infection. _Immunity_ 47, 1129–1141 (2017). e1125. Article CAS Google Scholar * Kojo, S.

et al. Priming of lineage-specifying genes by Bcl11b is required for lineage choice in post-selection thymocytes. _Nat. Commun._ 8, 702 (2017). Article ADS Google Scholar * Naoe, Y. et

al. Repression of interleukin-4 in T helper type 1 cells by Runx/Cbf beta binding to the Il4 silencer. _J. Exp. Med._ 204, 1749–1755 (2007). Article CAS Google Scholar * Kim, S. et al.

Licensing of natural killer cells by host major histocompatibility complex class I molecules. _Nature_ 436, 709–713 (2005). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar Download references

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We thank W.M. Yokoyama, D.K. Sojka, B. Plougastel-Douglas, and T. Egawa for helpful discussions, E. Park, M.D. Bern, J. Poursine-Laurent, L. Yang, and S.M. Taffner for

technical assistance, and K. Takeda for the IL-10-Venus mice. This study was supported by the “Kibou Project 2016” Startup Support for Young Researchers in Immunology (T.E.), JSPS KAKENHI

Grant Number 18H02647 (T.E.), Riken (Incentive Research Project, FY2017) (T.E.), Takeda Science Foundation (T.E.), Mochida Memorial Foundation for Medical and Pharmaceutical Research (T.E.),

and Suzuken Memorial Foundation (T.E.). AUTHOR INFORMATION AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Laboratory for Transcriptional Regulation, RIKEN Center for Integrative Medical Sciences (IMS), 1-7-22

Suehiro-cho, Tsurumi-ku, Yokohama, 230-0045, Japan Chizuko Miyamoto, Satoshi Kojo, Motoi Yamashita, Ichiro Taniuchi & Takashi Ebihara * Laboratory for Innate Immune Systems, RIKEN Center

for Integrative Medical Sciences (IMS), 1-7-22 Suehiro-cho, Tsurumi-ku, Yokohama, 230-0045, Japan Kazuyo Moro * Stem Cell Biology Group, Cancer Research UK Manchester Institute, The

University of Manchester, Wilmslow Road, Manchester, M20 4BX, UK Georges Lacaud * Laboratory for Immunogenetics, RIKEN Center for Integrative Medical Sciences (IMS), 1-7-22 Suehiro-cho,

Tsurumi-ku, Yokohama, 230-0045, Japan Katsuyuki Shiroguchi * Laboratory for Prediction of Cell Systems Dynamics, RIKEN Center for Biosystems Dynamics Research (BDR), Suita, Osaka, 565-0874,

Japan Katsuyuki Shiroguchi * JST PRESTO, Kawaguchi, 332-0012, Japan Katsuyuki Shiroguchi Authors * Chizuko Miyamoto View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed

Google Scholar * Satoshi Kojo View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Motoi Yamashita View author publications You can also search for this

author inPubMed Google Scholar * Kazuyo Moro View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Georges Lacaud View author publications You can also

search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Katsuyuki Shiroguchi View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Ichiro Taniuchi View author

publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Takashi Ebihara View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CONTRIBUTIONS

T.E. designed the experiments, analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript; C.M., S.K., and K.S. performed the experiments; M.Y. analyzed the RNA sequence and ChIP sequence data; K.M. and

G.L. supplied critical reagents and mice; and I.T. provided essential advice and helped write the manuscript. CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to Takashi Ebihara. ETHICS DECLARATIONS

COMPETING INTERESTS The authors declare no competing interests. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION JOURNAL PEER REVIEW INFORMATION: _Nature Communications_ thanks the anonymous reviewers for their

contribution to the peer review of this work. PUBLISHER’S NOTE: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION DESCRIPTION OF ADDITIONAL SUPPLEMENTARY FILES SUPPLEMENTARY DATA 1 SUPPLEMENTARY DATA 2 SUPPLEMENTARY DATA 3 REPORTING SUMMARY RIGHTS AND

PERMISSIONS OPEN ACCESS This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any

medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The

images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not

included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly

from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Miyamoto, C.,

Kojo, S., Yamashita, M. _et al._ Runx/Cbfβ complexes protect group 2 innate lymphoid cells from exhausted-like hyporesponsiveness during allergic airway inflammation. _Nat Commun_ 10, 447

(2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-08365-0 Download citation * Received: 25 October 2018 * Accepted: 08 January 2019 * Published: 25 January 2019 * DOI:

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-08365-0 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not

currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative