Play all audios:

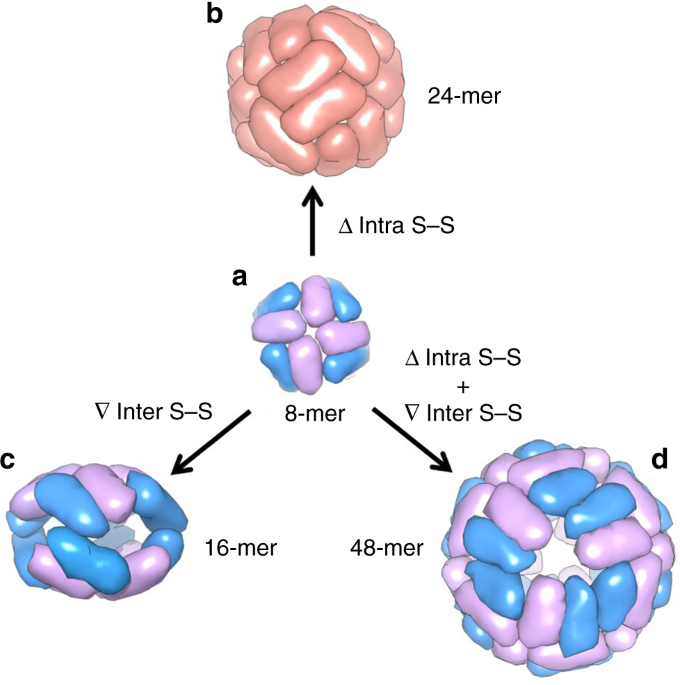

ABSTRACT Constructing different protein nanostructures with high-order discrete architectures by using one single building block remains a challenge. Here, we present a simple, effective

disulfide-mediated approach to prepare a set of protein nanocages with different geometries from single building block. By genetically deleting an inherent intra-subunit disulfide bond, we

can render the conversion of an 8-mer bowl-like protein architecture (NF-8) into a 24-mer ferritin-like nanocage in solution, while selective insertion of an inter-subunit disulfide bond

into NF-8 triggers its conversion into a 16-mer lenticular nanocage. Deletion of the same intra-subunit disulfide bond and insertion of the inter-subunit disulfide bond results in the

conversion of NF-8 into a 48-mer protein nanocage in solution. Thus, in the laboratory, simple mutation of one protein building block can generate three different protein nanocages in a

manner that is highly reminiscent of natural pentamer building block originating from viral capsids that self-assemble into protein assemblies with different symmetries. SIMILAR CONTENT

BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS PROTEIN INTERFACE REDESIGN FACILITATES THE TRANSFORMATION OF NANOCAGE BUILDING BLOCKS TO 1D AND 2D NANOMATERIALS Article Open access 11 August 2021 DESIGN OF

METAL-MEDIATED PROTEIN ASSEMBLIES VIA HYDROXAMIC ACID FUNCTIONALITIES Article 28 May 2021 HIERARCHICAL DESIGN OF PSEUDOSYMMETRIC PROTEIN NANOCAGES Article Open access 18 December 2024

INTRODUCTION Shape transformation is a popular phenomenon in nature, by which living organisms perform shape-to-function activities in response to the external environment1,2,3,4,5. Proteins

are nature’s most versatile building blocks, programmed at the genetic level to perform myriad functions and are largely responsible for the complexity of an organism6. In viral capsids, a

single protein fold can be evolved to form multiple oligomeric states with different symmetries7, but the shape transformation of proteins created by design in the laboratory has largely

been inaccessible. Generally, noncovalent interactions are mainly involved in the formation of the protein quaternary structures where subunit–subunit interactions (SSIs) are involved8,9,10.

Such noncovalent interactions at subunit–subunit interfaces are exquisitely controlled, which define the geometry of protein architectures. Although the protein architectures are usually

governed by noncovalent interactions at the subunit−subunit interfaces, the energetic contributions of individual residues to the stability of subunit−subunit interfaces are often unevenly

distributed11,12. To find the key individual residues responsible for SSIs could provide a solution to control the conversion of one quaternary structure into another13. Similarly, disulfide

bonds likewise play an important role in the formation and stability of proteins14. Disulfide bonds existing in proteins are relatively oxidative in the extracellular space15. Recently,

disulfide-functionalized nanoparticles and organic polymer hydrogels have been rapidly developed as delivery carriers;16 moreover, disulfide bonds have been exploited as bridges to construct

2D and 3D protein nanomaterials17,18. However, the function of disulfide bonds in the conversion between different protein architectures and in the fabrication of protein nanocages has yet

to be explored. Protein cages are widely distributed in nature to fulfill a variety of functions19, which usually have highly symmetrical structures constructed from versatile building

blocks. Self-assembled protein nanocages represent a class of nanoscale scaffolds that holds much promise for various applications19,20,21,22,23,24,25. However, the number and structure of

naturally occurring proteins are limited, thereby impeding their further applications as biotemplates or vehicles in the field of nanoscience and nanotechnology. To overcome this limitation,

different methods, including the matching rotational symmetry approach26,27, computational interface design28,29, and directed evolution have been explored to create different protein

cages20, but these approaches are usually engineering-intensive for protein surface and highly dependent on the accuracy of the design, thereby negatively impacting the biological activity

of the designed protein. To address these issues, we try to use a simple chemical-bonding approach to control SSIs, thereby constructing protein architectures with minimal design. We believe

that cysteine (Cys)-mediated disulfide bonds fit this approach well because (1) they are strong and reversible, and such properties can minimize the surface area to be designed, while

keeping them chemically tunable; and (2) they are easily designed and engineered by well-established chemical and genetic techniques. Herein, we report a set of discrete protein nanocages

with different sizes and geometries (24-mer, 16-mer, and 48-mer), which are constructed by using one single 8-mer bowl-like protein building block through deletion of one inherent

intra-subunit S–S bond formed within one subunit, insertion of inter-subunit S–S bonds at the protein interface, and deletion of the intra-subunit S–S bonds while insertion of the

inter-subunit S–S bonds, respectively (Fig. 1). This disulfide-mediated approach to the conversion between different protein assemblies opens up an avenue for protein assemblies with

unexplored properties. RESULTS CONVERSION OF 8-MER ARCHITECTURE INTO 24-MER NANOCAGE As a standard structural component among protein nanocages, ferritin exists ubiquitously in both

prokaryotes and eukaryotes. It is a nearly spherical 24-subunits protein with an exterior diameter of about 12 nm and a hollow cavity of 8 nm30,31. Owing to its cage-like morphology and

highly symmetrical structure, ferritin has been explored as a nanocarrier for the preparation of different nanomaterials19,22,23,24,32. Nevertheless, so far, the ferritin assembly has been

limited in scope to a single size and shape. Recently, by introduction of small (hexapeptide) deletion into helix D of each subunit13, we carried out the complete conversion of native 24-mer

ferritin nanocage into a 8-mer bowl-like non-native protein architecture in solution (Supplementary Figure 1), and this protein was referred to as NF-8. This fabricated protein assembly is

stable in different buffer solutions over the pH range of 6.0–9.0, and thus it has great potential as a building block to construct protein architectures13. Structurally, the 8-mer protein

is a heteropolymer that is composed of two different subunits (Hα and Hβ) that originate from the same polypeptide. During its self-assembly process, these two subunits form a dimer with a

ratio of 1:1, and then four of them assemble into an 8-mer protein architecture with _C__4_ symmetry13. Notably, there is an intra-subunit disulfide bond (Cys90–Cys102) formed within each Hα

subunit of NF-8, while the Hβ subunit is devoid of such disulfide bond. Structural analyses reveal that Cys90 in the BC loop is far away from Cys102 located at the C-helix in the Hβ subunit

or native HuHF subunit, but these two cysteines are in close proximity in the Hα subunit and thus form an intra-subunit S–S bond that causes an obvious shift of the C-helix to the direction

of the B-helix, while D-helix is moving to the opposite side (Supplementary Figure 2). We envisioned that this intra-subunit disulfide bond could play an important role in maintaining the

tertiary structure of the Hα subunit, thereby stabilizing the quaternary structure of NF-8. To test this idea, we planned to delete this intra disulfide bond by genetic modification (Fig.

2a), and then observed the possible structural changes due to such deletion. To this end, we made a mutant named Δ3C, where two cysteine residues (Cys90 and Cys102) related to the formation

of the intra-subunit S–S and another free cysteine (Cys130) were replaced by alanine (Ala), respectively (Supplementary Figure 3). Cys130 was removed to just prevent the production of any

possible inclusion body through incorrect disulfide bond linkage. After _E. coli_ cells expressing the proteins grew at 20 °C for 8 h, the resulting proteins were analyzed by native PAGE.

The yield of this mutant is about 40 mg per 1 L of culture medium under the present experimental conditions, which is similar to that of recombinant human H chain ferritin (HuHF). The

results showed that there are two overexpressed species, namely one major species with a larger molecular weight (MW) and another minor species having a smaller MW. In contrast, when the

expression of mutant Δ3C in _E. coli_ was carried out at 37 °C, the yield of these two protein species is reversed as shown in Supplementary Figure 4. To gain insight into the nature of

these two protein species, both of them were purified by a combination of gel and ion-exchange chromatography, followed by characterization. Native PAGE of these two proteins showed a single

band (Fig. 2b), indicating that they were purified to homogeneity. Analytical ultracentrifugation showed that the larger protein assembly in solution sedimented as a single discrete species

with s20,w = 17.28 S (Fig. 2c), which is very similar to that of wild-type (wt) HuHF (s20,w = 18.8 S)13, suggesting that it is also a 24-mer protein assembly, so it is referred to as

24-merΔ3C. In contrast, the smaller species was sedimented to obtain as s20,w = 7.20 S, which is nearly the same as that of NF-8 (s20,w = 7.4 S)13, suggesting that it is also a 8-mer protein

assembly, and is termed as 8-merΔ3C. Consistent with the above conclusion, transmission electron microscopy (TEM) analyses revealed that the exterior diameter of 24-merΔ3C is about 12 nm,

which is almost identical to that of native ferritin, while 8-merΔ3C has an exterior diameter of ~9 nm, a value being the same as the size of NF-813. To obtain detailed structural

information on 24-merΔ3C, we tried to crystallize this protein and eventually obtained qualified crystals suitable for X-ray diffraction. We solved the crystal structure at resolution of

3.104 Å (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). We found that 24-merΔ3C is composed of 24 subunits assembling into a ferritin-like nanocage (Supplementary Figure 4), approving the above hypothesis

that the deletion of the intra-subunit S–S bond of NF-8 leads to such conversion. The structural analyses revealed the large difference in structure between NF-8 and 24-merΔ3C. NF-8 has the

_C__4_ symmetry, while 24-merΔ3C has an octahedral symmetry, so this fabricated 24-mer protein has the three _C__4_, four _C__3_, and six _C__2_ rotation axes (Supplementary Figure 5). This

represents the first structural difference for these two proteins. It was also observed that the orientation of the side chain of Cys130 in NF-8 is nearly the same as that of Ala130 in

24-merΔ3C (Supplementary Figure 6), indicating that the above mutation of Cys130 into Ala almost has no effect on the conversion of NF-8 into 24-merΔ3C. The second difference in structure

between NF-8 and 24-merΔ3C is that NF-8 is a heteropolymeric protein containing equal numbers of Hα and Hβ subunits, while 24-merΔ3C is a homopolymer which consists of 24 identical subunits.

Notably, the structure of 24-merΔ3C subunit differs strikingly from that of Hα and Hβ subunits, and thus it is named as Hγ which also forms a four-α-helix bundle just like the subunit of

native HuHF as shown in Fig. 3a. This might be an important reason why 24 Hγ subunits in 24-merΔ3C are able to assemble into a ferritin-like hollow structure. However, the superposition of

Hγ and native HuHF subunits revealed that a shortage of an inherent α-helix in the middle of the D-helix is lost in the Hγ subunit (Fig. 3a). Consistent with this structural difference, we

found that the stability of 24-merΔ3C is lower than that of wt ferritin, namely, 24-merΔ3C can dissociate into subunits at pH 3.0 (Supplementary Figure 7), while wt HuHF disassembly requires

at least pH 2.025. Thus, the deletion of a single inherent intra-subunit S–S triggers the conversion of Hα and Hβ subunits of the NF-8 protein architecture into their Hγ analog, 24 of

which, therefore, assemble into a 24-mer protein nanocage (Fig. 3c), this corresponding to the possible conversion mechanism of NF-8 into 24-merΔ3C. To determine the possible difference in

structure between 8-merΔ3C and NF-8, the crystal structure of 8-merΔ3C was also resolved. Similar to NF-8, 8-merΔ3C also comprises eight of Hα- and Hβ-type subunits at a ratio of 1:1, which

assemble into a bowl-like structure with an outer diameter of around 9 nm (Fig. 4a). The crystal structure of 8-merΔ3C is in good agreement with its structure in solution characterized by

analytical ultracentrifugation and TEM (Figs. 2c, e). However, removal of the intra-subunit S–S bonds in NF-8 did not inhibit the formation of the Hα-type subunit in 8-merΔ3C, suggesting

that the intra-subunit S–S bonds are not essential stabilizing forces for the structure of Hα. Although the structure of 8-merΔ3C is similar to that of NF-8, their packing pattern in the

crystal is completely different from each other. For example, the side view of the crystal structure revealed that 8-merΔ3C molecules array in a repeating side-to-side pattern to form

two-dimensional (2D) protein layers (Fig. 4c), where two adjacent bowl-like 8-merΔ3C molecules having opposite orientations are connected by two salt bridges (Fig. 4d). The formed 2D layers

further arrange in the vertical direction to create 3D porous protein assemblies (Fig. 4b). In contrast, NF-8 exhibits a different packing pattern in its crystal where six of NF-8 protein

molecules assemble into a 48-mer protein cage13. It is worth noting that one polypeptide of mutant Δ3C is able to fold into three types of subunits: Hα, Hβ, and Hγ; subsequently, the first

two kinds of subunits co-assemble into 8-merΔ3C, while 24 of the third-type subunits self-assemble into 24-merΔ3C (Fig. 5). DESIGN OF A 16-MER NANOCAGE FROM NF-8 The above results

demonstrated that the intra-subunit S–S bond plays an important role in controlling protein tertiary and quaternary structure. We wonder whether inter-subunit S–S bonds can also be utilized

as a linkage for the construction of a discrete protein architecture by using the same building block. To this end, we also chose NF-8 as a building block to create another protein species.

Our approach is to insert an inter-subunit disulfide bond at the outer edge of each Hα subunit, which could bridge NF-8 molecules together to form a larger protein architecture. Upon

inspection, we deemed the amino acid position 144 (originally aspartic acid) located at the middle of the D-helix of the Hα subunit (Supplementary Figure 8) to be well suited for

constructing a motif for inter-subunit S–S interactions (Fig. 6a). The side chain at this position is protruded toward outside, and thus substitution of Asp144 by Cys could provide

sufficient room for such inter-subunit S–S interactions between protein building blocks. Based on these considerations, we made a NF-8 mutant named ∇C, in which only Asp144 was mutated to

Cys (Supplementary Figure 3). After _E. coli_ cells expressing mutant ∇C were lysed, we found that there was only one overexpressed band appearing in native PAGE, which exhibited a different

electrophoretic behavior from that of NF-8 (Fig. 6b), indicative of the formation of a larger protein. The yield of ∇C is around 30 mg per 1 L of culture medium. To gain insight into the

characteristics of mutant ∇C, we purified it to homogeneity (Fig. 6b). SDS-PAGE analyses revealed that this protein consists of one kind of subunit, the MW of which is about 20 kDa

(Supplementary Figure 9, inset). The accurate MW of this mutant subunit was obtained as 20592 Da by MALDI–TOF–MS (Supplementary Figure 9), being in agreement with its theoretical value

(20543 Da). The sedimentation coefficient of native mutant ∇C is ~12.10 S, a value being larger than that of NF-8 (s20,w = 7.20 S). Size-exclusion chromatography combined with multi-angle

light scattering (SEC-MALS) was performed to determine the MW of mutant ∇C in its native form. We found that this designed protein was eluted from a Superdex 200 10/300 GL (GE Healthcare)

column in a single peak at a volume of about 21.5 mL (Fig. 6d), giving the weight-averaged molecular mass as 318 ± 10 kDa, which is ~2-fold larger than that of NF-8 (165 ± 6 kDa),

demonstrating that it is a 16-mer protein assembly in solution, and therefore it is named as 16-mer∇C. Subsequently, we used TEM to visualize the morphology of 16-mer∇C with NF-8 as a

control sample. TEM results showed that 16-mer∇C exhibits nearly the same morphology and size as NF-8 (Supplementary Figure 10a, b), suggesting that mutant ∇C could be a NF-8 dimer, namely

two NF-8 building blocks polymerize in a face-to-face manner to form an oval-shaped 16-mer protein cage induced by the inter-subunit S–S bond. If this is the case, one would expect that iron

cores can be formed within 16-mer∇C because of its shell-like structure, whereas NF-8 cannot due to its open structure. As expected, TEM analyses showed that iron cores with 500

iron/protein shells can be successfully generated with 16-mer∇C as a biotemplate according to our reported method33; however, such iron cores cannot be observed with NF-8 under the same

experimental conditions (Supplementary Figure 10c, d); these findings approve the above conclusion that 16-mer∇C has a shell-like structure. To clarify the disulfide connectivity for

16-mer∇C, MS/MS analysis was performed according to a reported method34. As expected, the inherent intra-subunit S–S bond was identified to form between Cys90 and Cys102 (Supplementary

Figure 11). Additionally, it was found that an inter-subunit S–S bond formed between two Cys144 residues coming from two identical subunits, respectively (Fig. 7a, b), confirming our design.

Dynamic light scattering (DLS) analyses showed that the 16-mer∇C protein nanocage is stable over the pH range of 7.0–10.0 (Supplementary Figure 12). Taken together, it appears that the

incorporation of a well-placed inter-subunit disulfide bond has the good potential to build a discrete protein architecture. THE CONSTRUCTION OF A 48-MER NANOCAGE FROM NF-8 Either removal of

the inherent intra-subunit S–S or addition of the extra inter-subunit S–S can facilitate the conversion of NF-8 into different protein species. This raises an interesting question as to

what if we remove the intra-subunit S–S of NF-8 while inserting an extra S–S at the outside of NF-8 (Fig. 8a). To answer this question, we prepared the third NF-8 mutant termed Δ3C-∇C where

cysteine residues (Cys90, Cys102, and Cys130) were replaced by alanine (Ala) while Asp144 was mutated to Cys (Supplementary Figure 3). After _E. coli_ cells expressing this mutant were

lysed, we found that four overexpressed products occurred as shown in native PAGE (Supplementary Figure 13a), suggesting that one polypeptide can simultaneously produce four different

protein species. The total yield of these four species is about 45 mg per 1 L of culture medium under the present conditions. Three of them exhibited the nearly same electrophoretic behavior

as NF-8 (band 1), 16-mer∇C (band 2), and 24-merΔ3C (band 3), respectively, suggesting that they could have similar protein assemblies. After preliminary purification, we used TEM to

visualize the morphology of the mixture, and found the largest protein assembly, the exterior diameter of which is about 17 nm (Fig. 8b). To confirm this observation, analytical

ultracentrifugation analyses were carried out, likewise showing that there are four protein species in solution related to the mutant Δ3C-∇C. The first three peaks correspond to 8-mer,

16-mer, and 24-mer, respectively, based on their sedimentation coefficients, while the fourth peak represents a different kind of protein assembly with the largest sedimentation coefficient

of 22.50 S in solution (Supplementary Figure 13b). To obtain their structural information, this mixture was further purified by using size-exclusion chromatography, and eventually four

protein components could be separated (Fig. 8c). Subsequently, we used these four protein assemblies to screen for their suitable crystallization conditions, respectively. However, we only

found conditions which are suitable for the growth of crystals with the 24-merΔ3C-∇C and the above largest species, but not for 8-merΔ3C-∇C and 16-merΔ3C-∇C crystals. We first solved the

crystal structure of 24-merΔ3C-∇C (Supplementary Figure 14 and Supplementary Table 2). As expected, this protein consists of 24 Hγ-type subunits, the crystal structure of which is nearly the

same as that of 24-merΔ3C, confirming the above observation by native PAGE and analytical ultracentrifugation (Supplementary Figure 13a, b). For the above-mentioned largest protein species,

we found that two conditions are suitable for the growth of crystals, namely one condition having no Mg2+ and another condition containing Mg2+. Subsequently, these two conditions were

further optimized in a manual plate setup with hanging-drop vapor diffusion to increase crystal size and quality. Under the crystallization condition without Mg2+, we eventually obtained

large single crystals suitable for X-ray diffraction studies. We solved the crystal structures at a high resolution of 2.699 Å (Supplementary Figure 15, Supplementary Tables 1 and 2), and

found that this large protein species is a heteropolymer which consists of 48 subunits of Hα and Hβ at a ratio of 1:1, and thus it is named as 48-merΔ3C-∇C. The exterior and interior

diameter of this 48-mer is about 17 nm and 13 nm in crystals, respectively. Consistent with this observation, TEM analyses showed that the outer diameter of the 48-mer is also ~17 nm

(Supplementary Figure 16). Thus, controlling the disulfide bond in protein building blocks can facilitate the conversion of NF-8 into not only the 16-mer and 24-mer protein architectures,

but also an even larger 48-mer protein nanocage. It is worth noting that, similar to the mutant Δ3C, one polypeptide of the mutant Δ3C-∇C likewise forms Hα, Hβ, and Hγ subunits, and these

three subunits can simultaneously stay in one solution and assemble into 24-mer and 48-mer protein nanocages, these findings being in accordance with the above observation with the mutant

Δ3C (Fig. 5). Further crystal analyses revealed that no inter-subunit S–S bond was formed in the 48-merΔ3C-∇C nanocage. Agreeing with this finding, TEM analyses showed that, upon dissolving

the crystals in buffer, 48-merΔ3C-∇C molecules were degraded into small species after 24 h, the size of which is identical to that of NF-8, and then such small species were associated with

each other (Supplementary Figure 17a). These results suggested that 48-merΔ3C-∇C is unstable in solution, and it is constructed directly by using the 8-mer as building blocks. However, we

excitedly noted that the inter-subunit S–S bond formed at subunit–subunit interfaces of the 48-mer protein nanocage when its crystals grew under the crystallization conditions containing

Mg2+. The structure of the 48-mer protein nanocage in the presence of Mg2+ exhibited nearly the same geometry as the above-mentioned 48-mer with exterior and inner diameter of 17 nm and 13

nm, respectively (Fig. 9a). Except for the inter-subunit S–S bond, one magnesium ion is bound to two acidic residues (Glu141 and Glu141′) and two water molecules by coordination bonds at the

same subunit–subunit interfaces (Fig. 9b). Comparative analyses indicated that the formation of Mg2+ coordination bonds is a prerequisite for the generation of the inter-subunit S–S bonds

in the 48-mer (Fig. 9c). Why is Mg2+ coordination so important for the formation of the inter-subunit S–S? The answer to this question may lie in the difference in crystal structure between

these two 48-mer protein nanocages in the presence and absence of Mg2+. The formation of Mg2+coordination bonds with Glu141 causes a movement of the D-helix of two Hα subunits by 0.9 Å;

consequently, Cys144 and Cys144′ residues from two Hα subunits are in close proximity, resulting in the generation of the inter-subunit S–S bond (Figs. 9d–g). Consistent with the existence

of the inter-subunit S–S bonds in the protein crystal structure, we found that this large protein cage is stable in solution based on the fact that its size and shape kept unchanged over the

time range of 24 h (Supplementary Figure 17b and 17c) after the crystals were dissolved in buffer. Thus, the cooperation of the inter-subunit S–S and metal coordination bonds located at

subunit–subunit interfaces (Supplementary Figure 18) greatly improved the stability of the 48-mer protein nanocage. However, we found that protein association occurs to some extent with the

48-mer protein nanocage at 7.0 as suggested by DLS (Supplementary Figure 19). This phenomenon is most likely caused by the larger outer surface area (~900 nm2) of the 17-nm-diameter

nanocage, which would greatly increase the intermolecular interactions. In contrast, at pH 3.0, protein nanocage disassembly occurs, resulting in the formation of subunits (Supplementary

Figure 19). These results suggested that the pH stability of the 48-mer protein nanocage in solution is lower than that of other protein architectures (8-mer, 16-mer, and 24-mer).

Furthermore, stopped-flow UV-visible results showed that the rate of iron oxidation catalyzed by the 48-mer is similar to that of native HuHF at 8 Fe2+/subunit (Supplementary Figure 19c),

suggesting that such large assembly hardly affects the original ferroxidase activity. It has been known that ordered assembly of nanoscale building blocks depends on the assembly conditions.

We rationalized that the crystallization setup used in protein crystallography could be applicable to the study of the conversion of NF-8 into other protein architectures in solution. These

considerations combined with the fact that the stability of the 48-mer nanocage was greatly improved by the presence of magnesium ions raise the possibility that treatment of _E. coli_

(which expressed the mutant Δ3C-∇C) with magnesium salts could facilitate the conversion of NF-8 into the 48-mer. To test this hypothesis, we conducted another experiment where extra

magnesium salts were added to the medium for the culture of _E. coli_. After cells were lysed, native PAGE analyses showed that the amount of overexpressed 48-mer protein was pronouncedly

increased, while the 16-mer protein and 8-mer protein architectures were expressed to a much less level (Supplementary Figure 20a). Differently, the 24-mer overexpressed level was almost

unchanged in both the presence and absence of magnesium salts. Support for this view comes from TEM results showing that only two kinds of protein nanocages occurred in solution, namely the

24-mer and the 48-mer protein nanocages (Supplementary Figure 20b). These findings suggested that all of the 8-mer, 16-mer, and 48-mer are composed of Hα- and Hβ-type subunits, and thus they

can interconvert with each other at the level of the protein quaternary structure depending on experimental conditions. DISCUSSION While the conversion of protein assemblies into

symmetrical analogs with lower order by targeted disruption of noncovalent interactions at subunit interfaces has a long track record of success35,36,37,38,39, the conversion of low-order

symmetrical protein assembly into its analog with higher symmetry is a challenge. We have described here a protein-engineering approach to convert the 8-mer protein assembly with _C__4_

symmetry into the 16-mer, 24-mer, and 48-mer protein nanocages with higher symmetry by controlling the intra- or inter-subunit disulfide bond. More interestingly, the fabricated protein

nanocages (16-mer, 24-mer, and 48-mer) is composed of three different types of subunits (Hα, Hβ, and Hγ) which are derived from one polypeptide; Hα and Hβ subunits are responsible for the

formation of the 16-mer and 48-mer, while the Hγ subunit corresponds to the generation of the 24-mer. This approach has allowed us to address the significance of both intra- and

inter-subunit disulfide bonds in protein assembly and to gain specific insights into either the formation of subunit or subunit interactions that direct protein nanocage assembly. The

mechanism of the conversion of the 8-mer into three different protein nanocages can be divided into two categories. The first one is referred to as a “subunit refolding” mechanism which

takes place at the level of protein tertiary structure mediated by intra-subunit S–S bonds. The conversion of NF-8 into 24-merΔ3C belongs to the first. Based on the crystal structure, it is

clear that the initial Hα and Hβ subunits of NF-8 are converted into the Hγ subunit in 24-merΔ3C upon the deletion of the intra-subunit S–S (Fig. 3). We believe that the conversion of NF-8

into 24-merΔ3C is most likely derived from the contribution of the intra-subunit S–S bond to the stability of the protein architecture. Support for this idea comes from the observation that

the melting point (_T__m_) of the 8-mer bowl-like NF-8 protein is about 76 °C, while its analog 8-merΔ3C’s _T__m_ decreases to 73 °C due to a dearth of the intra-subunit S–S bond

(Supplementary Figure 21). The difference in _T__m_ reflects the contribution of the intra-subunit S–S bond to the protein stability. Interestingly, we found that the _T__m_ of 24-merΔ3C (83

°C) is higher than that of NF-8, which is an important reason why NF-8 can convert into 24-merΔ3C through the above-mentioned subunit refolding mechanism. Differently, the fact that both

NF-8 and 48-mer protein nanocages consist of Hα and Hβ subunits (Fig. 9) suggests that NF-8 can serve as building blocks to directly construct the 48-mer protein nanocage at the level of the

quaternary structure through the inter-subunit S–S linkage at protein interfaces. This corresponds to the second conversion mechanism. It has to be mentioned that the presence of Mg2+

during the construction of the 48-mer not only leads to the formation of metal coordination bond with amino acid residues, but also facilitates the generation of the inter-subunit S–S bond

between Cys144 and Cys144′ (Fig. 9). These two different types of chemical bonds are cooperative to stabilize the structure of the 48-mer protein nanocage. Agreeing with this view, the

above-mentioned 48-mer protein nanocage did not generate when the 8-mer protein architecture (NF-8) was incubated with Mg2+ in vitro at different pH values (6.0, 7.0, and 9.0) (Supplementary

Figure 22). It is not surprising because NF-8 is not able to form the inter-subunit S–S bond due to a dearth of Cys144 (Supplementary Figure 3). These findings emphasize the importance of

the cooperation of both the metal coordination and the inter-subunit S–S bonds for the construction of the stable 48-mer protein nanocage. The assembling manner of the 48-merΔ3C-∇C protein

nanocage controlled by Mg2+ is reminiscent of the formation of ferritin from _Archaeoglobus fulgidus_. In the absence of ferrous ion, this specific ferritin occurs in solution as dimeric

species, while these dimeric species self-assemble into 24-meric cage-like structures induced by addition of ferrous ions40,41,42. Here, the occurrence of assemblies (16-mer, 24-mer, and

48-mer) with the 8-mer as building blocks recalls among natural proteins the case of clathrin coats. It has been known that clathrin can assemble into several regular assemblies, such as

78-mer, 108-mer, and 180-mer43. Thus, our reported construction of three different protein nanocages (16-mer, 24-mer, and 48-mer) from the 8-mer as building blocks provides a model to study

the mechanism of natural protein architectures. The construction of different protein nanocages from NF-8 also reminds us of the formation of viral capsids. In the structures of the viral

capsids, the pentamer is the common building block that can be used to build a variety of assemblies with different symmetries7. Protein nanocages hold the great promise of ease of

functionalization, intrinsic biocompatibility, and versatile platforms for encapsulation and delivery of a wide variety of non-physiological cargo molecules. Such properties have been

difficult to reach with other protein or biomolecule assemblies. Therefore, it is of crucial importance to establish methods to construct such protein assemblies. Our results established a

simple, effective method by which protein nanocages with different symmetries can be created from one kind of protein building block by disulfide-mediated conversion. It is worth noting that

both intra- and inter-subunit disulfides can be employed to build protein nanocages. The utilization of the disulfide bond to control protein assembly is attractive from the structural

perspective at two different levels: whereas the directionality and strength in the intra-subunit disulfide bond formed within the subunit can affect the geometry of the subunit structure

and thereby controlling the formation of protein architecture, the inter-subunit disulfide bond formed at subunit–subunit interfaces offers the ability to construct multi-subunit protein

assemblies at the level of the quaternary structure. The combination of the metal coordination bond and the inter-subunit S–S bond provides an alternative approach to improve the stability

of the constructed protein nanocages. Compared with the reported strategy for the preparation of protein nanocages that usually requires intensive re-engineering of protein interfaces, the

present construction approach that focuses on the conversion between different protein architectures by the disulfide bond motif is conceptually and operationally simple, which could bypass

the immense challenge of controlling the noncovalent interactions that hold protein assemblies together. METHODS PROTEIN PREPARATION The coding sequence of NF-8 was synthesized and cloned

into the pET-3a plasmid (Novagen). Mutagenesis of NF-8 was performed with the fast site-directed mutagenesis kit (TIANGEN Biotech Co., Ltd.). The primers used in this work are listed in

Supplementary Table 3. After the transfection of plasmid into the _E. coli_ strain BL21 (DE3), cells were grown at 37 °C with further induction by 200 μM isopropyl

β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside at 20 or 37 °C. The cells were collected by centrifugation after induction and resuspended in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) with a concentration of bacteria as 40 g/L.

Subsequently, ultrasonication was used to disrupt the cells. The resulting protein was enriched from the supernatant by fractionation of ammonium sulfate, followed by dialysis against 50 mM

Tris-HCl (pH 8.0). Then crude protein was subjected to an ion-exchange column, followed by gradient elution with 0–0.5 M NaCl. After further purification by a gel filtration column (Superdex

200, GE Healthcare), equilibrated with 50 mM Tris-HCl and 150 mM NaCl (pH 8.0), the resultant protein was used for the following experiments. TRANSMISSION ELECTRON MICROSCOPY (TEM) ANALYSES

TEM experiments were performed as below: 10 μL of protein was applied to a carbon-coated copper grid. After excess solution removed with filter paper, the samples were negatively stained

for 2 min with 2% uranyl acetate. TEM micrographs were imaged at 80 kV through a Hitachi H-7650 scanning electron microscope. ANALYTICAL ULTRACENTRIFUGATION SEDIMENTATION ANALYSES The

experiments were performed at 10 ℃ in an XL-I analytical ultracentrifuge (Beckman–Coulter) equipped with Rayleigh Interference detection (655 nm). Protein samples (110 μl) were centrifuged

at 50,000 r.p.m. for 8 h. All samples were prepared in buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 7.5). Interference profiles were collected every 6 min. Data analysis was conducted with the software Sedfit

11.7, GUSSI, and SEDPHAT (monomer–dimer model). SEC-MALS ANALYSIS SEC-MALS experiments for mutant ∇C and NF-8 were performed using a DAWN-HELEOS II detector (Wyatt Technologies) coupled to a

Superdex 200 column (GE Healthcare) in buffer (50 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, pH = 8.0) with a flow rate of 0.4 mL/min. Mutant ∇C and NF-8 (~1.0 mg/mL) was injected and data were analyzed using

ASTRA 6 software (Wyatt Technologies) to determine the weight-averaged molecular mass. LC–MS/MS SPECTRUM Gel bands of proteins were cut for in-gel digestion, followed by mass spectrometry

analyses38. Sequencing grade-modified trypsin was used in gel digestion at 37 ℃ overnight. The peptides were extracted twice with 50% acetonitrile aqueous solution containing 1%

trifluoroacetic acid for 1 h. Then the further concentrated peptides were separated with a Thermo-Dionex Ultimate 3000 HPLC system, which was directly interfaced with a Thermo Orbitrap

Fusion Lumos mass spectrometer. Mobile phase A consisted of 0.1% formic acid, and mobile phase B was added with 100% acetonitrile. An LTQ-Orbitrap mass spectrometer was operated in a

data-dependent acquisition mode using Xcalibur 4.1 software. MS/MS spectra from each LC–MS/MS run were searched against the ferritin sequence using ByonicTM Version 2.8.2 (Protein Metrics)

searching algorithm. DYNAMIC LIGHT SCATTERING (DLS) DLS experiments were performed at 25 °C using a Viscotek model 802 dynamic light scattering instrument (Viscotek, Europe). The OmniSIZE

2.0 software was used to calculate the size distribution of samples. For all samples, protein concentration was 1.0 μM, and proteins were buffered in 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0 with different

concentrations of NaCl. DIFFERENTIAL SCANNING CALORIMETRY (DSC) A differential scanning calorimeter (Nano-DSC, TA Instruments) was used for measurement with the following settings:

temperature was set from 30 to 100 °C with an increasing rate at 1.0 °C/min. A result of control buffer was used to subtract the baseline for melting temperature (_T__m_) calculation by

software. Precision data of each protein were calculated by repeated scans in duplicate. CRYSTALLIZATION, DATA COLLECTION, AND STRUCTURE DETERMINATION Purified mutants were buffered in 10 mM

Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) after three-times dialysis, and were then concentrated to 10 mg/mL. Their crystals were obtained by the hanging-drop vapor diffusion method at different conditions, which

were shown in Supplementary Table 1. X-ray diffraction data were collected at Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility (SSRF) (BL17U and BL19U) with merging and scaling by HKL-3000 software.

Data-processing statistics are displayed in Supplementary Table 2. The structures were determined by molecular replacement using coordinates of human H ferritin and NF-8 (PDB code 2FHA and

5GN8) as the initial model using the MOLREP program in the CCP4 program. Following refinement and manual rebuilding were carried out by PHENIX and COOT, respectively. All figures of the

resulting structures were produced using PyMOL. REPORTING SUMMARY Further information on experimental design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

DATA AVAILABILITY Coordinates and structure factors are deposited in the Protein Data Bank under the accession PDB IDs: 6IPQ (24-merΔ3C), 6IPC (8-merΔ3C), 6J7G (24-merΔ3C-∇C), 6IPP

(48-merΔ3C-∇C①), and 6IPO (48-merΔ3C-∇C②). Other data are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request. The source data underlying Figs. 2b and 6b and Supplementary Figs.

4, 9, 13a, 17c and 20a are provided as a Source Data file. REFERENCES * Lay, C. L., Lee, M. R., Lee, H. K., Phang, I. Y. & Liang, X. Y. Transformative two-dimensional array

configurations by geometrical shape-shifting protein microstructures. _ACS Nano_ 10, 9708–9717 (2015). Article Google Scholar * Rothemund, P. W. K. Folding DNA to create nanoscale shapes

and patterns. _Nature_ 440, 297–302 (2006). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Delebecque, C. J., Lindner, A. B., Silver, P. A. & Aldaye, F. A. Organization of intracellular reactions

with rationally designed RNA assemblies. _Science_ 333, 470–474 (2011). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Aggeli, A. et al. Responsive gels formed by the spontaneous self-assembly of

peptides into polymeric β-sheet tapes. _Nature_ 386, 259–262 (1997). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Waller, P. J. et al. Chemical conversion of linkages in covalent organic frameworks.

_J. Am. Chem. Soc._ 48, 15519–15522 (2016). Article Google Scholar * Brodin, J. D. et al. Metal-directed, chemically tunable assembly of one-, two- and three-dimensional crystalline

protein arrays. _Nat. Chem._ 4, 375–382 (2012). Article CAS Google Scholar * Zhao, X., Fox, J. M., Olson, N. H., Baker, T. S. & Young, M. J. In vitro assembly of cowpea chlorotic

mottle virus from coat protein expressed in _Escherichia coli_ and in vitro-transcribed viral cDNA. _Virology_ 207, 486–494 (1995). Article CAS Google Scholar * Hudson, K. L. et al.

Carbohydrate-aromatic interactions in proteins. _J. Am. Chem. Soc._ 137, 15152–15160 (2015). Article CAS Google Scholar * Johnson, E. R. et al. Revealing noncovalent interactions. _J. Am.

Chem. Soc._ 132, 6498–6506 (2010). Article CAS Google Scholar * Huard, D. J. E., Kane, K. M. & Tezcan, F. A. Re-engineering protein interfaces yields copper-inducible ferritin cage

assembly. _Nat. Chem. Biol._ 9, 169–178 (2013). Article CAS Google Scholar * Clackson, T. & Wells, J. A. A hot spot of binding energy in a hormone-receptor interface. _Science_ 267,

383–386 (1995). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Moreira, I. S., Fernandes, P. A. & Ramos, M. J. Hot spots: a review of the protein-protein interface determinant amino acid residues.

_Protein.: Struct., Funct., Bioinf_ 68, 803–812 (2007). Article CAS Google Scholar * Zhang, S. L. et al. “Silent” amino acid residues at key subunit interfaces regulate the geometry of

protein nanocages. _ACS Nano_ 10, 10382–10388 (2016). Article CAS Google Scholar * Fass, D. & Thorpe, C. Chemistry and enzymology of disulfide cross-linking in proteins. _Chem. Rev._

118, 1169–1198 (2018). Article CAS Google Scholar * Sevier, C. S. & Kaiser, C. A. Formation and transfer of disulfide bonds in living cells. _Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Bio_ 3, 836–847

(2002). Article CAS Google Scholar * Lee, M. H. et al. Disulfide-cleavage-triggered chemosensors and their biological applications. _Chem. Rev._ 113, 5071–5109 (2013). Article CAS

Google Scholar * Suzuki, Y. et al. Self-assembly of coherently dynamic, auxetic, two-dimensional protein crystals. _Nature_ 533, 369–373 (2016). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar *

Ringler, P. & Schulz, G. E. Self-assembly of proteins into designed networks. _Science_ 302, 106–109 (2003). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Uchida, M. et al. Biological containers:

protein cages as multifunctional nanoplatforms. _Adv. Mater._ 19, 1025–1042 (2007). Article CAS Google Scholar * Wörsdörfer, B., Woycechowsky, K. J. & Hilvert, D. Directed evolution

of a protein container. _Science_ 331, 589–592 (2011). Article ADS Google Scholar * Wörsdörfer, B., Pianowski, Z. & Hilvert, D. Efficient in vitro encapsulation of protein cargo by an

engineered protein container. _J. Am. Chem. Soc._ 134, 909–911 (2012). Article Google Scholar * Lin, X. et al. Hybrid ferritin nanoparticles as activatable probes for tumor imaging.

_Angew. Chem., Int. Ed._ 50, 1569–1572 (2011). Article CAS Google Scholar * Liang, M. et al. H-ferritin-nanocaged doxorubicin nanoparticles specifically target and kill tumors with a

single-dose injection. _Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA_ 111, 14900–14905 (2014). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Zhen, Z. et al. Ferritin nanocages to encapsulate and deliver

photosensitizers for efficient photodynamic therapy against cancer. _ACS Nano_. 7, 6988–6996 (2013). Article CAS Google Scholar * Chen, L. et al. Encapsulation of β-carotene within

ferritin nanocages greatly increases its water-solubility and thermal stability. _Food Chem._ 149, 307–312 (2014). Article CAS Google Scholar * Padilla, J. E., Colovos, C. & Yeates,

T. O. Nanohedra: using symmetry to design self assembling protein cages, layers, crystals, and filaments. _Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA_ 98, 2217–2221 (2001). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar

* Lai, Y. T., Cascio, D. & Yeates, T. O. Structure of a 16-nm cage designed by using protein oligomers. _Science_ 336, 1129–1129 (2012). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * King, N.

P. et al. Accurate design of co-assembling multi-component protein nanomaterials. _Nature_ 51, 103–108 (2014). Article ADS Google Scholar * Bale, J. B. et al. Accurate design of

megadalton-scale two-component icosahedral protein complexes. _Science_ 353, 389–394 (2016). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Arosio, P., Ingrassia, R. & Cavadini, P. Ferritins: a

family of molecules for iron storage, antioxidation and more. _Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Gen. Subj._ 589−599, 2009 (1790). Google Scholar * Bou-Abdallah, F. The iron redox and hydrolysis

chemistry of the ferritins. _Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Gen. Subj._ 1800, 719–731 (2010). Article CAS Google Scholar * Li, J. Y. et al. Scara5 is a ferritin receptor mediating

non-transferrin iron delivery. _Dev. Cell._ 16, 35–46 (2009). Article CAS Google Scholar * Zhang, S. et al. The size flexibility of ferritin nanocage opens a new way to prepare

nanomaterials. _Small_ 1701045, 1–6 (2017). Google Scholar * Li, X. et al. The gain of hydrogen peroxide resistance benefits growth fitness in mycobacteria under stress. _Protein Cell_ 5,

182–185 (2014). Article Google Scholar * Beernink, P. T. & Tolan, D. R. Subunit interface mutants of rabbit muscle aldolase form active dimers. _Protein Sci._ 3, 1383–1391 (1994).

Article CAS Google Scholar * Beernink, P. T. & Tolan, D. R. Disruption of the aldolase A tetramer into catalytically active monomers. _P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA_ 93, 5374–5379 (1996).

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Horovitz, A., Bochkareva, E. S. & Girshovich, A. S. The N terminus of the molecular chaperonin GroEL is a crucial structural element for its

assembly. _J. Biol. Chem._ 268, 9957–9959 (1993). CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Chen, H. N. & Woycechowsky, K. J. Conversion of a dodecahedral protein capsid into pentamers via minimal

point mutations. _Biochemistry_ 51, 4704–4712 (2012). Article CAS Google Scholar * Wang, W. et al. Selective elimination of the key subunit interfaces facilitates conversion of native

24-mer protein nanocage into 8‑mer nanorings. _J. Am. Chem. Soc._ 140, 14078–14081 (2018). Article CAS Google Scholar * Johnson, E., Cascio, D., Sawaya, M. R., Gingery, M. & Schröder,

I. Crystal structures of a tetrahedral open pore ferritin from the hyperthermophilic Archaeon _Archaeogloubus fulgidus_. _Structure_ 4, 637–648 (2005). Article Google Scholar * Katherine,

W. et al. Thermophilic ferritin 24mer assembly and nanoparticle encapsulation modulated by interdimer electrostatic repulsion. _Biochemistry_ 56, 3596–3606 (2017). Article Google Scholar

* Sana, B., Johnson, E. & Lim, S. The unique self-assembly property of _Archaeoglobus fulgidus_ ferritin and its implications on molecular release from the protein cage. _Biochim.

Biophys. Acta, Gen. Subj._ 1850, 2544–2551 (2015). Article CAS Google Scholar * Fotin, A. et al. Molecular model for a complete clathrin lattice from electron cryomicroscopy. _Nature_

432, 573–579 (2004). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (nos. 31730069 and

31671805) and the Initiative Postdocs Supporting Program of China (no. BX201700284). The Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility (SSRF) is especially acknowledged for beam time. We thank the

staffs from BL17U1/BL18U1/19U1 beamline of the National Center for Protein Sciences Shanghai (NCPSS) at Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility for assistance during data collection. We

also thank the staffs in Tsinghua University Branch of China National Center for Protein Sciences, Beijing for technical assistance. AUTHOR INFORMATION AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Beijing

Advanced Innovation Center for Food Nutrition and Human Health, College of Food Science & Nutritional Engineering, China Agricultural University, Key Laboratory of Functional Dairy,

Ministry of Education, 100083, Beijing, China Jiachen Zang, Hai Chen, Xiaorong Zhang, Chenxi Zhang & Guanghua Zhao * Center of Biomedical Analysis, Tsinghua University, 100084, Beijing,

China Jing Guo * School of Food Science and Technology, National Engineering Research Center of Seafood, Dalian Polytechnic University, 116034, Dalian, China Ming Du Authors * Jiachen Zang

View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Hai Chen View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar *

Xiaorong Zhang View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Chenxi Zhang View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed

Google Scholar * Jing Guo View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Ming Du View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed

Google Scholar * Guanghua Zhao View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CONTRIBUTIONS G.Z. and M.D. conceived and directed the project and wrote

the paper. J.Z. designed and performed experiments, analyzed data, and co-wrote the paper. H.C. performed the crystal data collection. X.Z. and C.Z. performed experiments and co-wrote the

paper. J.G. performed the protein mass spectrometry. CORRESPONDING AUTHORS Correspondence to Ming Du or Guanghua Zhao. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS The authors declare no

competing interests. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION JOURNAL PEER REVIEW INFORMATION: _Nature Communications_ thanks Ivan Dmochowski and the other anonymous reviewer for their contribution to the

peer review of this work. PUBLISHER’S NOTE: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION

SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION REPORTING SUMMARY SOURCE DATA SOURCE DATA RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS OPEN ACCESS This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International

License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source,

provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons

license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by

statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Zang, J., Chen, H., Zhang, X. _et al._ Disulfide-mediated conversion of 8-mer

bowl-like protein architecture into three different nanocages. _Nat Commun_ 10, 778 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-08788-9 Download citation * Received: 05 November 2018 *

Accepted: 23 January 2019 * Published: 15 February 2019 * DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-08788-9 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read

this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative