Play all audios:

ABSTRACT Identification of habitable planets beyond our solar system is a key goal of current and future space missions. Yet habitability depends not only on the stellar irradiance, but

equally on constituent parts of the planetary atmosphere. Here we show, for the first time, that radiatively active mineral dust will have a significant impact on the habitability of

Earth-like exoplanets. On tidally-locked planets, dust cools the day-side and warms the night-side, significantly widening the habitable zone. Independent of orbital configuration, we

suggest that airborne dust can postpone planetary water loss at the inner edge of the habitable zone, through a feedback involving decreasing ocean coverage and increased dust loading. The

inclusion of dust significantly obscures key biomarker gases (e.g. ozone, methane) in simulated transmission spectra, implying an important influence on the interpretation of observations.

We demonstrate that future observational and theoretical studies of terrestrial exoplanets must consider the effect of dust. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS ATMOSPHERIC CARBON

DEPLETION AS A TRACER OF WATER OCEANS AND BIOMASS ON TEMPERATE TERRESTRIAL EXOPLANETS Article 28 December 2023 PERSISTENCE OF FLARE-DRIVEN ATMOSPHERIC CHEMISTRY ON ROCKY HABITABLE ZONE

WORLDS Article 21 December 2020 UNDERSTANDING PLANETARY CONTEXT TO ENABLE LIFE DETECTION ON EXOPLANETS AND TEST THE COPERNICAN PRINCIPLE Article 18 February 2022 INTRODUCTION Even before the

discovery of the first potentially habitable terrestrial exoplanets1, researchers have speculated on the uniqueness of life on Earth. Of particular interest are tidally locked planets,

where the same side of the planet always faces the star, since this is considered the most likely configuration for habitable planets orbiting M-dwarf stars2,3, which make up the majority of

stars in our galaxy. In the absence of observational constraints, numerical models adapted from those designed to simulate our own planet have been the primary tool to understand these

extraterrestrial worlds4,5,6,7,8. But most studies so far have focussed on oceanic aquaplanet scenarios, because water-rich planets are one of the likely outcomes of planetary formation

models9, the hydrological cycle is of key importance in planetary climate and the definition of habitability requires stable surface liquid water. For a planet’s climate to be stable enough

for a sufficiently long period of time to allow the development of complex organisms (e.g., around 3 billion years for Earth10), the presence of significant land cover may be required. The

carbon–silicate weathering cycle, responsible on Earth for the long-term stabilisation of CO2 levels in a volcanic environment, acts far more efficiently on land than at the ocean floor11.

Some studies have attempted to simulate the effects of the presence of land12,13,14,15,16, demonstrating how it would affect the climate and atmospheric circulation of a tidally locked

planet, such as Proxima b5,7. More specific treatments of land surface features, such as topography, have only been briefly explored7,17. Mineral dust is a significant component of the

climate system whose effects have been hitherto neglected in climate modelling of exoplanets. Mineral dust is a class of atmospheric aerosol lifted from the planetary surface and comprising

the carbon–silicate material that forms the planetary surface (it should not be conflated with other potential material suspended in a planetary atmosphere, such as condensable species

(clouds) or photochemical haze). Dust is raised from any land surface that is relatively dry and free from vegetation. Dust can not only cool the surface by scattering stellar radiation, but

also warm the climate system through absorbing and emitting infra-red radiation. Within our own solar system, dust is thought to be widespread in the atmosphere of Venus18, and is known to

be an extremely important component of the climate of Mars, which experiences planetary-scale dust storms lasting for weeks at a time19,20. Even on Earth, dust can play a significant role in

regional climate21,22 and potentially in global long-term climate23. Here, we demonstrate the importance of mineral dust on a planet’s habitability. Given our observations of the solar

system, it is reasonable to assume that any planet with a significant amount of dry, ice- and vegetation-free landcover, is likely to have significant quantities of airborne dust. Here, we

show for the first time that mineral dust plays a significant role in climate and habitability, even on planets with relatively low land fraction, and especially on tidally locked planets.

We also show that airborne dust affects near-infra-red transmission spectra of exoplanets, and could confound future detection of key biomarker gases such as ozone and methane. Airborne

mineral dust must therefore be considered when studying terrestrial exoplanets. RESULTS SCHEMATIC MECHANISMS We consider two template planets, a tidally locked planet orbiting an M dwarf

(denoted TL), with orbital and planetary parameters taken from Proxima b, and a non-tidally locked planet orbiting a G dwarf (denoted nTL), with orbital and planetary parameters taken from

Earth. The choice of parameters is merely to give relatable examples; the results presented are generic and applicable to any planet in a similar state. We also consider the planets to be

Earth-like in atmospheric composition, i.e., 1-bar surface pressure and a nitrogen-dominated atmosphere, as this is the most well-understood planetary atmosphere, and the only one known to

be inhabited. For each of these planets, we consider a range of surface land-cover amounts and configurations, designed to both explore the parameter space that may exist and understand in

which scenarios dust is important. Starting from well-understood aquaplanet simulations6 derived using a state-of-the-art climate model24, we increase the fraction of land in each model grid

cell equally, until the surface is completely land. This experiment (denoted Tiled) acts to both increase the amount of land available for dust uplift, whilst reducing the availability of

water, and thus the strength of the hydrological cycle, without requiring knowledge of continent placement. For the TL case, we additionally conduct simulations in which a continent of

increasing size is placed at the substellar point (denoted Continents). This produces a fundamentally different heating structure from the central star15, and significantly increases the

effect of the dust for small land fractions, whilst allowing a strong hydrological cycle to persist. For each planet and climate configuration, we run two simulations, one without dust,

called NoDust, equivalent to all previous studies of rocky exoplanets, and one in which dust can be lifted from the land surface, transported throughout the atmosphere and interacted with

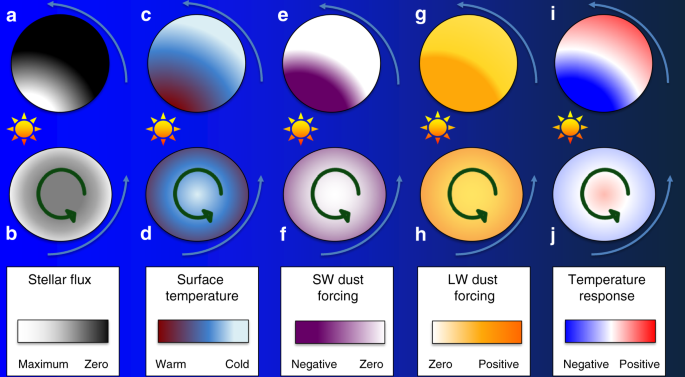

the stellar and infra-rad radiation and atmospheric water, called Dust. The mechanisms through which dust affects planetary climate are illustrated in Fig. 1. Incoming stellar radiation is

concentrated over a smaller area on the TL planet (Fig. 1a) compared with the nTL case (Fig. 1b). Strong surface winds on the dayside of TL allow for much greater uplift of dust than the

equatorial doldrums of nTL. The super-rotating jet on TL is more efficient at transporting this dust to cooler regions on the nightside (Fig. 1c), than the more complex atmospheric

circulation on nTL is at transporting dust to the poles (Fig. 1d). The radiative forcing, or change in surface energy balance caused by airborne dust, is therefore weaker for nTL than TL. As

a result, the nTL planet is broadly cooled by dust (Fig. 1j) because the airborne dust’s infra-red greenhouse effect (Fig. 1h) is cancelled out by the stellar radiation changes due to

scattering and absorption by airborne dust (Fig. 1f). However, the TL planet is strongly cooled on its warm dayside by similar mechanisms, but warmed on its nightside (Fig. 1i) because the

airborne dust’s infra-red greenhouse effect (Fig. 1g) has no stellar radiation change to offset it (Fig. 1e). HABITABLE ZONE CHANGES Figure 2 shows two key metrics we use to quantify the

outer and inner edges of the habitable zone for our template planets. The outer edge of the habitable zone is likely to be controlled by the temperature at which CO2 condenses25, which for

the concentrations and surface pressures considered here, is at ≈125 K. Keeping the minimum temperature above this threshold is therefore a key requirement for maintaining a CO2 greenhouse

effect, and preventing a planet’s remaining atmospheric constituents from condensing out. Figure 2a shows that for the TL case, the presence of dust always acts to increase the minimum

temperature found on the planet (blue and magenta lines). The effect of dust is to sustain a greenhouse effect at a lower stellar irradiance than when dust is absent, implying that dust

moves the outer edge of the habitable zone away from a parent star. The effect is not especially sensitive to the specific arrangement of the land (magenta vs. blue lines in Fig. 2a), but is

very sensitive to the fraction of the surface covered by land; the approximate change in stellar radiation at the outer edge of the habitable zone is over 150 W m−2 for a totally

land-covered planet, but even up to 50 W m−2 for a planet with the same land coverage as Earth. Such results are in stark contrast to the nTL case, for which dust always acts to reduce the

minimum surface temperature (cyan line in Fig. 2a), moving the outer edge of the habitable zone inwards. The inner edge of the habitable zone is likely to be controlled by the rate at which

water vapour is lost to space, often termed the moist greenhouse26,27,28. The strength of the water-vapour greenhouse effect increases with surface temperature, eventually leading to

humidities in the middle atmosphere that are large enough to allow significant loss of water to space. Stratospheric water-vapour content is therefore a key indicator of when an atmosphere

will enter a moist greenhouse. Figure 2b shows that for all our simulations, the effect of dust is to reduce stratospheric water-vapour content, i.e., dust suppresses the point at which a

moist greenhouse will occur and moves the inner edge of the habitable zone nearer to the parent star. The effect on the habitable zone can be approximately quantified by utilising additional

simulations done with increased or reduced stellar flux and a constant tiled land fraction of 70% (Table 3). They show that stratospheric water vapour scales approximately logarithmically

with stellar flux, allowing us to infer that the 30–60% reduction in stratospheric water vapour caused by dust (shown in Fig. 2b) roughly corresponds to a stellar flux reduction of 30 – 60 W

m−2. In contrast to the effect on the outer edge, both our TL and nTL simulations result in a reduction in stratospheric water vapour when including dust, demonstrating that the inward

movement of the inner edge of the habitable zone is a ubiquitous feature of atmospheric dust. However, here the magnitude of the effect is more dependent on the arrangement of the land, and

therefore more uncertain. Supplementary Notes 1 and 2 give more details on this. In summary, radiatively active atmospheric dust increases the size of the habitable zone for our tidally

locked planets, both by moving the inner edge inwards and outer edge outwards. For our non-tidally locked planets, both the inner and outer edges of the habitable zone move inwards, so the

consequences for habitable zone size depend on which effect is stronger. The exact size of the habitable zone is a subject of much debate2,27,28,29, and how well our results can be

extrapolated to previous estimates of its size are covered in the ‘Discussion’. But to illustrate the potential importance of dust, conservative estimates from Kasting et al.2 suggest a

stellar irradiance range of ~750 W m−2 from the inner to the outer edge. Figure 2a shows that the effect of dust is equivalent to changing the stellar irradiance by up to 150 W m−2, thereby

moving the outer edge of the habitable zone by up to 10% in either direction. Figure 3 illustrates the effects of dust on climate for the TL case in more detail. We show the results for the

100% land simulation where the dust effect is the strongest, and although the effect is weakened with lower fractions of land, the mechanisms remain the same. The dust particles are lifted

from the surface on the dayside of the planet, since uplift can only occur from non-frozen surfaces. There they are also strongly heated by incoming stellar radiation. The larger particles

cannot be transported far before sedimentation brings them back to the surface, but the smaller particles can be transported around the planet by the strong super-rotating jet expected in

the atmospheres of tidally locked planets30. The smaller dust sizes are therefore reasonably well-mixed throughout the atmosphere, and able to play a major role in determining the radiative

balance of the nightside of the planet. This highlights an important uncertainty not yet discussed—our assumption that surface dust is uniformly distributed amongst all size categories. As

only the small- to mid-sized dust categories play a major role in determining the planetary climate, increasing or decreasing the amount of surface dust in these categories can increase or

decrease the quantitative effects. Similarly, the precise formulation of the dust-uplift parameterisation can have a similar quantitative effect on the results presented. More discussion is

given in Supplementary Note 1, but neither uncertainty changes the qualitative results presented. The coldest temperatures are found in the cold-trap vortices on the nightside of the planet

(Fig. 3a), which without dust are ≈135 K. The effect of dust is to raise the temperature reasonably uniformly by ≈25 K across the nightside of the planet (Fig. 3b), significantly raising the

temperature of the cold traps above the threshold for CO2 condensation. The increase in surface temperature arises because of a corresponding increase in the downwelling infra-red radiation

received by the surface of the nightside of the planet (Fig. 3c, d), which is approximately doubled compared with a dust-free case. Supplementary Note 2 explores some of the more detailed

responses of the different land surface configurations that are shown in Fig. 2. However, in all cases, the effect on the habitable zone and mechanisms for the change are consistent with

those described above, and are likely to be significant for any continental configuration and even for low fractions of land. SIMULATED OBSERVATIONS A key question regarding airborne mineral

dust is how it would affect the interpretation of potential future spectra of terrestrial exoplanets. Figure 4 presents synthetic observations created from our model output combined with

the PandExo simulator31 of the NIRSpec (G140M, G235M and G395M modes) instrument on the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), following the method described in Lines et al.32. We focus here on

the TL case, and compare the relatively dry 100% land-cover simulation with the 20% landcover arranged as a continent simulation, to demonstrate how even planets with low dust loading and a

strong hydrological cycle can be affected. We additionally consider the 20% land-cover simulation to have an atmospheric composition that is Earth-like, i.e., it contains the key observable

potential biomarker gases oxygen, ozone and methane33 in present-day Earth concentrations. Adding these gases does not greatly affect the climatic state6, but can significantly alter the

observed spectra. We consider a target object with the apparent magnitude of Proxima Centauri, as stars near this range are the most likely candidates for observing in the near future

(Proxima b itself does not transit34, but that does not invalidate our results for similar planets around similar stars). We discuss how our results change for dimmer stars such as

TRAPPIST-1 in Supplementary Note 3. Figure 4 shows that airborne dust effectively introduces a new continuum absorption into the spectrum, which completely obscures many of the minor

absorption peaks similar to previous studies of hotter planets32,35, some of which are associated with potential biomarker gases, such as methane (2.3 and 3.3 μm) and ozone (4.7 μm). An

oxygen feature at 0.76 μm is also significantly obscured in the dusty spectrum, and although it falls outside the spectral range of JWST, is similarly unlikely to be prominent enough if it

was within the observable spectrum. Importantly, biomarker gas features are obscured even when dust loading is relatively low (Fig. 4c, d), i.e., even relatively wet planets with a strong

hydrological cycle are prone to having important spectral peaks being obscured from observation by dust. DISCUSSION Given the radiative properties of dust, and the dependence of its impact

on the climate on land fraction (Fig. 2), it could potentially produce a strong negative feedback for planets undergoing significant water loss at the inner edge of the habitable zone. As

water is lost and the fraction of the surface covered by ocean decreases, the amount of dust that is suspended in the atmosphere will likely increase, which in turn cools surface

temperatures, quite dramatically in the case of a tidally locked planet, reducing the amount of water vapour in both the lower and middle atmosphere. Airborne dust can therefore act as a

temporary brake on water loss from planets at the inner edge of the habitable zone in a similar manner to the ocean fraction/water-vapour feedback13. However, how dust interacts with other

mechanisms affecting the inner edge of the habitable zone requires further study. For example, the potential bistable state of planets with water locked on the nightside36, which may also

widen the habitable zone, may be partly offset by the presence of dust if the warmer nightside (due to the mechanisms discussed here) allows some of the water to be liberated back to the

dayside. Estimates of the outer edge of the habitable zone29 are also typically made with much higher CO2 partial pressures than those considered here (up to 10 bar). It is unclear that such

high CO2 concentrations could be achieved in the presence of land, due to increased weathering activity preventing further CO2 buildup37. If they could, the quantitative effect of dust will

depend on a range of compensating uncertainties. For example, dust uplift should be enhanced due to higher surface stresses in a higher-pressure atmosphere. However, dust transport to the

nightside may be reduced in the weaker super-rotating jet due to reduced day–night-temperature contrasts38. Our results have implications for studies of the history of our own planet before

terrestrial vegetation covered large areas, with a particular example being the faint young Sun problem of Archaean Earth39. The land masses that are believed to have emerged during this

period will have been unvegetated, and therefore a significant source of dust uplift into the atmosphere if dry and not covered in ice. As we have shown, this dust would have a cooling

effect on the planetary climate, potentially making the faint young Sun problem harder to resolve. However, it is also possible that microbial mats might have covered large areas of the land

surface before vegetation evolved. The exact nature of such cover, and how much it would hinder dust lifting into the atmosphere, is yet to be quantified. It is clear that the possible

presence of atmospheric dust must be considered when interpreting observations. The feature-rich spectrum observed from a dust-free atmosphere containing water vapour, oxygen, ozone and

methane (Fig. 4c) is transformed into a flat, bland spectrum where only major CO2 peaks are visible above the background dust continuum (Fig. 4d). Observations returning a spectrum such as

this could easily be misinterpreted as being caused by a dry atmosphere containing only nitrogen and CO2, i.e., Fig. 4d interpreted as Fig. 4a. The result would be a potentially very

interesting planet being characterised as dry, rocky and lifeless. On the other hand, if spectra are obtained that can unambiguously place a limit on dust generation, such results imply a

mechanism that inhibits dust lifting, whether it be some combination of a very small land fraction, significant ice or vegetation cover or other dust-inhibiting mechanisms: such a result

would also be of great interest to those interpreting observations. Finally, our results have wide-ranging consequences for future studies of the habitability of terrestrial rocky planets.

Such studies should include models of airborne dust as well as observational constraints. Furthermore, our results strongly support the continued collaboration between observational and

modelling communities, as they demonstrate that observations alone cannot determine the size of the habitable zone: it crucially depends on properties of the planetary atmosphere, which are

presently only accessible via climate modelling. METHODS NUMERICAL MODEL SET-UP Our general circulation model of choice is the GA7 science configuration of the Met Office Unified Model24, a

state-of-the-art climate model that incorporates within it a mineral dust parameterisation40,41, which includes uplift from the surface, transport by atmospheric winds, sedimentation, and

interaction with radiation, clouds and precipitation. The parameterisation comprises nine bins of different-sized dust particles (0.03–1000 μm). The largest three categories (>30 μm)

represent the precursor species for atmospheric dust; these are the large particles that are not electrostatically bound to the surface, but can be temporarily lifted from the surface by

turbulent motions. They quickly return to the surface under gravitational effects, and as such are not transported through the atmosphere (they do not travel more than a few metres).

However, they are important because their subsequent impact with the surface is what releases the smaller particles into the atmosphere. These smaller six categories (<30 μm) are

transported by the model’s turbulence parameterisation42, moist convection scheme43 and resolved atmospheric dynamics44. They can return to the surface under gravitational settling,

turbulent mixing and washout from the convective or large-scale precipitation schemes45. The absorption and scattering of short- and long-wave radiation by dust particles are based on

optical properties calculated from Mie theory, assuming spherical particles, and each size division is treated independently. The land surface configuration is almost identical to that

presented in Lewis et al.15, i.e., a bare-soil configuration of the JULES land surface model set to give the planet properties of a sandy surface. Our key difference is the use of a

lower-surface albedo (0.3). The land is at sea-level altitude with zero orography and a roughness length of 1 × 10−3 m for momentum and 2 × 10−5 m for heat and moisture (although these are

reduced when snow is present on the ground). The soil moisture is initially set to its saturated value, but evolves freely to its equilibrium state. Land is assumed to comprise dust of all

sizes, uniformly distributed across the range. The dust parameterisation is used in its default Earth set-up, and naturally adapts to the absence of vegetation, suppresses uplift in wetter

regions and prevents it from frozen or snow-covered surfaces. The ocean parameterisation is a slab ocean of 2.4-m mixed-layer depth with no horizontal heat transport, as was used in Boutle

et al.6, and includes the effect of sea ice on surface albedo following the parameterisation described in Lewis et al.15. It is worth noting that whilst the set-up implies an infinite

reservoir of both water in the ocean and dust on the land, this is not actually a requirement of the results—all that is required is enough water/dust to support that which is suspended in

the atmosphere and deposited in areas unfavourable for uplift (e.g., the nightside of the TL planet), and that some equilibrium state is achieved whereby additional water/dust deposited in

areas unfavourable for uplift can be returned to areas where uplift can occur, e.g., basal melting of glaciers. The orbital and planetary parameters for our two template planets are given in

Table 1. To simplify the analysis slightly, both planets are assumed to have zero obliquity and eccentricity. Atmospheric parameters are given in Table 2. Again, for simplicity, we assume

that the atmospheric composition is nitrogen-dominated with trace amounts of CO2 for the control experiments investigating the role of dust on the atmosphere. However, because of the

important role that potential biomarker gases, such as oxygen, ozone and methane, have in the transmission spectrum, when discussing simulated observables, we include these gases at an

abundance similar to that of present-day Earth. Table 3 summarises the 28 experiments and their parameters that are described in this paper. DATA AVAILABILITY All data used in this study are

available from https://doi.org/10.24378/exe.2284. CODE AVAILABILITY The Met Office Unified Model is available for use under licence, see

http://www.metoffice.gov.uk/research/modelling-systems/unified-model. REFERENCES * Borucki, W. J. et al. Kepler-62: a five-planet system with planets of 1.4 and 1.6 Earth radii in the

habitable zone. _Science_ 340, 587–590 (2013). Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Kasting, J. F., Whitmire, D. P. & Reynolds, R. T. Habitable zones around main sequence stars.

_Icarus_ 101, 108–128 (1993). Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Barnes, R. Tidal locking of habitable exoplanets. _Celest. Mech. Dyn. Astr._ 129, 509–536 (2017). Article ADS

MathSciNet Google Scholar * Joshi, M. M., Haberle, R. M. & Reynolds, R. T. Simulations of the atmospheres of synchronously rotating terrestrial planets orbiting M dwarfs: conditions

for atmospheric collapse and the implications for habitability. _Icarus_ 129, 450–465 (1997). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Turbet, M. et al. The habitability of Proxima Centauri b

II. Possible climates and observability. _Astron. Astrophys._ 596, A112 (2016). Article CAS Google Scholar * Boutle, I. A. et al. Exploring the climate of Proxima B with the Met Office

Unified Model. _Astron. Astrophys._ 601, A120 (2017). Article CAS Google Scholar * Del Genio, A. D. et al. Habitable climate scenarios for Proxima Centauri b with a dynamic ocean.

_Astrobiology_ 19, 99–125 (2019). Article ADS PubMed Google Scholar * Fauchez, T. J. et al. TRAPPIST-1 habitable atmosphere intercomparison (THAI). Motivations and protocol version 1.0.

_Geosci. Model Dev._ 13, 707–716 (2020). Article ADS Google Scholar * Tian, F. & Ida, S. Water contents of Earth-mass planets around M dwarfs. _Nat. Geosci._ 8, 177–180 (2015).

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Nisbet, E. G. & Sleep, N. H. The habitat and nature of early life. _Nature_ 409, 1083–1091 (2001). Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar *

Abbot, D. S., Cowan, N. B. & Ciesla, F. J. Indication of insensitivity of planetary weathering behavior and habitable zone to surface land fraction. _Astrophys. J._ 756, 178 (2012).

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Joshi, M. Climate model studies of synchronously rotating planets. _Astrobiology_ 3, 415–427 (2003). Article ADS PubMed Google Scholar * Abe, Y.,

Abe-Ouchi, A., Sleep, N. H. & Zahnle, K. J. Habitable zone limits for dry planets. _Astrobiology_ 11, 443–460 (2011). Article ADS PubMed Google Scholar * Yang, J., Boué, G.,

Fabrycky, D. C. & Abbot, D. S. Strong dependence of the inner edge of the habitable zone on planetary rotation rate. _Astrophys. J. Lett._ 787, L2 (2014). Article ADS Google Scholar *

Lewis, N. T. et al. The influence of a substellar continent on the climate of a tidally locked exoplanet. _Astrophys. J._ 854, 171 (2018). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Way, M. J. et

al. Climates of warm Earth-like planets. I. 3D model simulations. _Astrophys. J. Suppl. Ser._ 239, 24 (2018). Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Way, M. J. et al.

Was Venus the first habitable world of our solar system? _Geophys. Res. Lett._ 43, 8376–8383 (2016). Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Greeley, R. et al. Aeolian

features on Venus: preliminary Magellan results. _J. Geophys. Res._ 97, 13319–13345 (1992). Article ADS Google Scholar * Zurek, R. W. Martian great dust storms: an update. _Icarus_ 50,

288–310 (1982). Article ADS Google Scholar * Kahre, M. A., Murphy, J. R. & Haberle, R. M. Modeling the Martian dust cycle and surface dust reservoirs with the NASA Ames general

circulation model. _J. Geophys. Res._ 111, E6 (2006). Article Google Scholar * Lambert, F. et al. Dust-climate couplings over the past 800,000 years from the EPICA Dome C ice core.

_Nature_ 452, 616–619 (2008). Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Kok, J. F., Ward, D. S., Mahowald, N. M. & Evan, A. T. Global and regional importance of the direct

dust-climate feedback. _Nat. Comms._ 9, 241 (2018). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Ridgwell, A. J. & Watson, A. J. Feedback between aeolian dust, climate, and atmospheric CO2 in

glacial time. _Paleoceanography_ 17, 1059 (2002). Article ADS Google Scholar * Walters, D. et al. The Met Office Unified Model Global Atmosphere 7.0/7.1 and JULES Global Land 7.0

configurations. _Geosci. Model Dev._ 12, 1909–1963 (2019). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Turbet, M., Forget, F., Leconte, J., Charnay, B. & Tobie, G. CO2 condensation is a serious

limit to the deglaciation of Earth-like planets. _Earth Planet. Sci. Lett._ 476, 11–21 (2017). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Kasting, J. F. Runaway and moist greenhouse atmospheres

and the evolution of Earth and Venus. _Icarus_ 74, 472–494 (1988). Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Zsom, A., Seager, S., de Wit, J. & Stamenković, V. Toward the minimum

inner edge distance of the habitable zone. _Astrophys. J._ 778, 109 (2013). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Leconte, J., Forget, F., Charnay, B., Wordsworth, R. & Pottier, A.

Increased insolation threshold for runaway greenhouse processes on Earth-like planets. _Nature_ 504, 268–271 (2013). Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Kopparapu, R. K. et al.

Habitable zones around main-sequence stars: new estimates. _Astrophys. J._ 765, 131 (2013). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Showman, A. P. & Polvani, L. M. Equatorial superrotation

on tidally locked exoplanets. _Astrophys. J._ 738, 71 (2011). Article ADS Google Scholar * Batalha, N. E. et al. PandExo: a community tool for transiting exoplanet science with JWST &

HST. _PASP_ 129, 064501 (2017). Article ADS Google Scholar * Lines, S. et al. Exonephology: transmission spectra from a 3D simulated cloudy atmosphere of HD 209458b. _MNRAS_ 481, 194–205

(2018). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Schwieterman, E. W. et al. Exoplanet biosignatures: a review of remotely detectable signs of life. _Astrobiology_ 18, 663–708 (2018). Article

ADS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Jenkins, J. S. et al. Proxima Centauri b is not a transiting exoplanet. _MNRAS_ 487, 268–274 (2019). Article ADS Google Scholar * Kreidberg,

L. et al. Clouds in the atmosphere of the super-Earth exoplanet GJ 1214b. _Nature_ 505, 69–72 (2014). Article ADS PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Leconte, J. et al. 3D climate modeling of

close-in land planets: circulation patterns, climate moist bistability, and habitability. _Astron. Astrophys._ 554, A69 (2013). Article Google Scholar * Kite, E. S., Gaidos, E. &

Manga, M. Climate instability on tidally locked exoplanets. _Astrophys. J._ 743, 41 (2011). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Fauchez, T. J. et al. Impact of clouds and hazes on the

simulated JWST transmission spectra of habitable zone planets in the TRAPPIST-1 system. _Astrophys. J._ 887, 194 (2019). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Charnay, B. et al. Exploring the

faint young Sun problem and the possible climates of the Archean Earth with a 3-D GCM. _J. Geophys. Res._ 118, 10,414–10,431 (2013). CAS Google Scholar * Woodward, S. Modeling the

atmospheric life cycle and radiative impact of mineral dust in the Hadley Centre climate model. _J. Geophys. Res._ 106, 18155–18166 (2001). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Woodward, S.

Mineral Dust in HadGEM2. Technical Report No. 87 (Hadley Centre, Met Office, Exeter, 2011). * Lock, A. P., Brown, A. R., Bush, M. R., Martin, G. M. & Smith, R. N. B. A new boundary

layer mixing scheme. Part I: scheme description and single-column model tests. _Mon. Weather Rev._ 128, 3187–3199 (2000). Article ADS Google Scholar * Gregory, D. & Rowntree, P. R. A

mass flux convection scheme with representation of cloud ensemble characteristics and stability-dependent closure. _Mon. Weather Rev._ 118, 1483–1506 (1990). Article ADS Google Scholar *

Wood, N. et al. An inherently mass-conserving semi-implicit semi-lagrangian discretisation of the deep-atmosphere global nonhydrostatic equations. _Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc._ 140, 1505–1520

(2014). Article ADS Google Scholar * Wilson, D. R. & Ballard, S. P. A microphysically based precipitation scheme for the Meteorological Office Unified Model. _Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc._

125, 1607–1636 (1999). Article ADS Google Scholar Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I.B. and J.M. acknowledge the support of a Met Office Academic Partnership secondment. We

acknowledge use of the MONSooN system, a collaborative facility supplied under the Joint Weather and Climate Research Programme, a strategic partnership between the Met Office and the

Natural Environment Research Council. NM was partly funded by a Leverhulme Trust Research Project Grant that supported some of this work alongside a Science and Technology Facilities Council

Consolidated Grant (ST/R000395/1). This work also benefited from the 2018 Exoplanet Summer Programme in the Other Worlds Laboratory (OWL) at the University of California, Santa Cruz, a

programme funded by the Heising-Simons Foundation. AUTHOR INFORMATION AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * College of Engineering, Mathematics and Physical Sciences, University of Exeter, Exeter, EX4

4QL, UK Ian A. Boutle, F. Hugo Lambert, Nathan J. Mayne, Duncan Lyster, James Manners, Robert Ridgway & Krisztian Kohary * Met Office, FitzRoy Road, Exeter, EX1 3PB, UK Ian A. Boutle

& James Manners * School of Environmental Sciences, University of East Anglia, Norwich, NR4 7TJ, UK Manoj Joshi Authors * Ian A. Boutle View author publications You can also search for

this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Manoj Joshi View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * F. Hugo Lambert View author publications You can also

search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Nathan J. Mayne View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Duncan Lyster View author

publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * James Manners View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Robert Ridgway

View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Krisztian Kohary View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar

CONTRIBUTIONS I.B. ran the simulations and produced most of the figures and text. M.J. had the original idea and provided guidance, Fig. 1 and contributions to the text. F.H.L. and N.M.

provided guidance and contributions to the text. D.L. investigated the role of continents as a Masters project. J.M. provided scientific and technical advice. R.R. produced the synthetic

observations in Fig. 4. K.K. provided technical support. CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to Ian A. Boutle. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS The authors declare no competing

interests. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION PEER REVIEW INFORMATION _Nature Communications_ thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer

reports are available. PUBLISHER’S NOTE Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION

SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION PEER REVIEW FILE RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS OPEN ACCESS This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use,

sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative

Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated

otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds

the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Reprints and

permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Boutle, I.A., Joshi, M., Lambert, F.H. _et al._ Mineral dust increases the habitability of terrestrial planets but confounds biomarker

detection. _Nat Commun_ 11, 2731 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-16543-8 Download citation * Received: 09 December 2019 * Accepted: 05 May 2020 * Published: 09 June 2020 * DOI:

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-16543-8 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not

currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative