Play all audios:

ABSTRACT The _Pseudomonas putida_ phenol-responsive regulator DmpR is a bacterial enhancer binding protein (bEBP) from the AAA+ ATPase family. Even though it was discovered more than two

decades ago and has been widely used for aromatic hydrocarbon sensing, the activation mechanism of DmpR has remained elusive. Here, we show that phenol-bound DmpR forms a tetramer composed

of two head-to-head dimers in a head-to-tail arrangement. The DmpR-phenol complex exhibits altered conformations within the C-termini of the sensory domains and shows an asymmetric

orientation and angle in its coiled-coil linkers. The structural changes within the phenol binding sites and the downstream ATPase domains suggest that the effector binding signal is

propagated through the coiled-coil helixes. The tetrameric DmpR-phenol complex interacts with the σ54 subunit of RNA polymerase in presence of an ATP analogue, indicating that DmpR-like

bEBPs tetramers utilize a mechanistic mode distinct from that of hexameric AAA+ ATPases to activate σ54-dependent transcription. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS ALLOSTERIC ACTIVATION

MECHANISM OF DRID, A WYL-DOMAIN CONTAINING TRANSCRIPTION REGULATOR Article Open access 29 April 2025 STRUCTURAL INSIGHTS INTO TRANSCRIPTION REGULATION OF THE GLOBAL OMPR/PHOB FAMILY

REGULATOR PHOP FROM _MYCOBACTERIUM TUBERCULOSIS_ Article Open access 13 February 2025 THE BACTERIAL MULTIDRUG RESISTANCE REGULATOR BMRR DISTORTS PROMOTER DNA TO ACTIVATE TRANSCRIPTION

Article Open access 08 December 2020 INTRODUCTION The AAA+ family of ATPases is involved in various essential cellular processes. The bacterial enhancer binding (bEBP) subgroup of AAA+

proteins couple ATPase hydrolysis to initiation of transcription by σ54-RNA polymerase (σ54-RNAP)1. Many bEBPs belong to two-component systems, in which a membrane-bound histidine kinase

senses and transfers a signal from the environment to a corresponding response regulator to allow σ54-dependent promoter activity2. In contrast, some bEBPs are single-component sensory

regulators that directly bind effector molecules to achieve the same outcome3. DmpR (di-methyl phenol regulator) from _Pseudomonas putida_ KCTC 1452 (also known as CapR) is a

single-component bEBP that serves as a sensor of phenolic compounds4,5,6. In habitats contaminated by phenol and other aromatic pollutants, catabolism of these compounds is mediated by

tightly regulated operons that encode specialized suites of enzymes necessary for the sequential breakdown of recalcitrant compounds (e.g., toluene, xylene, cresols and other aromatic

ring-containing hydrocarbons)7. DmpR has also been widely used in engineering of bacteria and the development of whole-cell biosensors8,9,10. As is typical of bEBPs, DmpR consists of three

domains: (1) a sensory domain consisting of a vinyl-4-reductase (V4R) scaffold that functions in binding of an aromatic effector molecule11,12,13, (2) a conserved central AAA+ ATPase domain

bearing the bEBP-specific GAFTGA motif that is involved in coupling ATP hydrolysis to the restructuring of σ54-RNAP, and (3) a DNA binding domain that interacts with the palindromic upstream

activating sites (UASs) situated ~100–200 bp upstream from the σ54 promoter14. The B-linker that connects the sensory domain and the ATPase domain plays an important role in relaying the

effector binding signal to allow ATP hydrolysis15. In hexameric bEBPs with ring structures, higher-ordered oligomers induce formation of the catalytic active site at the interface between

adjacent ATPase subunits16. DmpR share high sequence homology with other aromatic-responsive bEBPs, such as XylR, TouR, PoxR and MopR, and this subgroup are known to transition from inactive

dimers to active oligomers upon the binding of an aromatic effector compound as a prerequisite for their capacity to direct σ54-dependent transcription1,17. Although the ATPase domains of

bEBPs generally mediates oligomerization into the active multimeric form, the internal signal transduction mechanism that results in oligomerization upon aromatic effector binding is not yet

fully understood. In particular, the exact number of subunits within the active oligomer and how they are arranged to enable a productive interaction with σ54-RNAP has remained unknown for

more than two decades. Similarly, the mechanism underlying negative regulation mediated by the sensory domain—so that truncates lacking this domain exhibit aromatic effector-independent

transcriptional promoting activity—has likewise not been fully explained18. Here, we determined the oligomerization status of DmpR by a single-molecule fluorescence imaging technique,

present a tetrameric structure of the phenol-bound DmpR complex and demonstrate its capacity to interact with σ54. As the report of a tetrameric bEBP capable of interacting with σ54, the

conformational change observed in the DmpR-phenol complex provides a structural basis for understanding the signal transduction activation mechanism of DmpR-like single-component bEBPs.

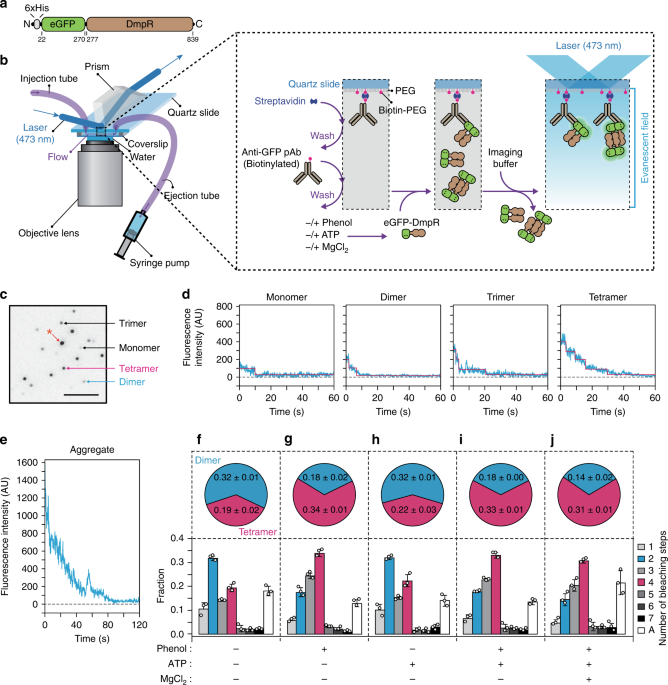

RESULTS PHENOL PROMOTES TETRAMERIC ASSOCIATION Upon the addition of a phenolic ligand, DmpR forms oligomers which are required to promote transcription19. We first examined the formation of

oligomers in response to the addition of phenol using purified full-length DmpR bearing an N-terminal 6 × His tag (DmpRWT, purity >95%; 66 kDa). As assessed by blue native (BN)-PAGE

analysis, in the absence of phenol, DmpRWT appeared as a mixture of dimers (~132 kDa) and tetramers (~264 kDa). When incubated with 1 mM phenol, the band corresponding to the dimer shifted

to reflect the higher molecular weight of the DmpRWT tetramer (Supplementary Fig. 1a). A change in the oligomeric sate of DmpRWT by phenol was also observed in size exclusion chromatography

(SEC) and in dynamic light scattering (DLS), respectively (Supplementary Fig. 1b, c). Addition of ATP analogues (ANP-PNP or ATPγS), or DNA containing its specific binding sites (upstream

activating sequences, UASs) did not change the tetrameric association of DmpRWT (Supplementary Fig. 1d). DmpRWT exhibited a marginal increase in DNA binding activity in the presence of

phenol (_K_D value ~ 387 nM) as compared to the absence of phenol (~476 nM) (Supplementary Fig. 1e). Consistent with these findings, multi-angle light scattering (MALS) analysis also showed

a protein peak with a molecular weight of ~280 kDa upon the addition of phenol in both the presence and the absence of ATPγS, indicating that DmpRWT predominantly forms a tetramer in

response to phenol (Supplementary Fig. 1f). The presence of a tetrameric subpopulation before addition of phenol presumably resulted from binding of _E. coli_ derived aromatic metabolites as

has been observed for some other aromatic hydrocarbon binding proteins11,12,20,21. To confirm tetramer formation upon phenol binding, we used single-molecule photobleaching (SMPB)22,23. We

generated a fusion containing fluorescent eGFP and N-terminally 6 × His-tagged DmpRWT (Fig. 1a). The fusion protein was surface-immobilized using a biotinylated anti-GFP antibody. Stepwise

bleaching signals from eGFP were recorded using total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) microscopy (Fig. 1b). A TIRF image of eGFP-DmpRWT showed clearly separate fluorescent spots

(Fig. 1c). Discrete steps were observed from individual eGFP-DmpRWT fluorescence time traces (Fig. 1d). Although there were ~18% of protein aggregates (Fig. 1e), eGFP-DmpRWT exhibited a

photobleaching distribution that corresponds to a mixture of multiple oligomeric states. In the absence of phenol, a major fraction of molecules (~32%) showed two-step photobleaching, which

is indicative of dimers. One-step (monomers), three-step (trimers) and four-step (tetramers) photobleachings were observed in around 11, 14 and 19% of the population, respectively (Fig. 1f).

One-step bleaching from dimeric eGFP-DmpRWT and less-than-four-step bleaching from tetrameric eGFP- DmpRWT could originate from incomplete eGFP maturation22,24,25. The eGFP maturation was

estimated to be 85% from the ratio between a protein concentration measured from the 280-nm absorbance and an eGFP fluorophore concentration measured from 488-nm absorbance. There were

hardly any oligomers that underwent more than five photobleaching steps within the populations. Upon the addition of phenol, a majority of the molecules (~34%) exhibited four-step bleaching,

while ~17% of the molecules exhibited two-step bleaching, indicating that phenol promotes an increase of the tetrameric population at the expense of the dimer population (Fig. 1g, i, j). No

change was observed upon the addition of ATP (Fig. 1h–j). Together, these results show that phenol promotes tetramer formation by DmpRWT and this oligomerization is independent of ATP.

STRUCTURE OF THE TETRAMERIC DMPRΔD-PHENOL COMPLEX Purification and crystallization of DmpRWT was hampered by a limited amount of full-length protein due to its low solubility and aggregation

as inclusion bodies in _E. coli_. Based on a solubility profile analysis and preliminary tests, we designed a truncated DmpR derivative (aa 18–481) that is soluble and produced at

sufficient levels in _E. coli_. This truncated protein, DmpRΔD, has an N-terminal 6 × His tag that replaces the first 15 residues, lacks the DNA binding domain, and carries serine

substitutions of two cysteine residues (C119S/C137S) that were anticipated to be located at the protein surface. DmpRΔD has a phenol binding affinity (_K_D = ~12 μM) similar to full-length

DmpR (_K_D = ~16 μM)19 and likewise exhibits tetrameric oligomerization in the presence of phenol (Supplementary Fig. 2a, b). The determined crystal structure of DmpRΔD shows a phenol

molecule bound to the sensory domain of each protomer. The sensory and ATPase domains are connected by an ~35 Å long helical B-linker. The protomer topology exhibits a ‘dumbbell-like’

structure with approximate dimensions of 110 × 55 × 70 Å (Fig. 2a). The DmpRΔD-phenol complex is a dimer-of-dimers with overall dimensions of 150 × 75 × 70 Å (Fig. 2b). The two protomers (P1

and P2) form an elongated intertwined P1/P2 dimer through extensive interactions between the related sensory domains and parallel coiled-coil B-linkers in a head-to-head orientation with a

buried surface area of 2895 Å2 (Fig. 2c). The two dimers—P1/P2 and P3/P4—form the tetramer, which has an antiparallel head-to-tail assembly that places the four ATPase domains at the central

core of the complex. The complex, with dimeric sensory domains at either end, adopts an overall elliptical rod-like shape. Since the two DmpRΔD C-termini are located next to each other due

to the twofold symmetry, the DNA binding domains that are missing in truncated DmpRΔD would be present as pairs, and those from the P1 and P3 protomers would be on one side and those from

the P2 and P4 protomers would be on the opposite side of the centre of the complex, as depicted in Fig. 2d. The formation of the DmpRΔD-phenol complex buries a surface area of ~26,800 Å2

(33% of the combined surfaces) between the protomers. The P1/P2 sensory domain dimer packs against the ATPase domains in the P3/P4 dimer in such a way that the Val53 and Ile58 residues in

the P1 sensory domain interact with Phe312 in the GAFTGA motif (aa 310–315) in the P3 ATPase domain (Supplementary Fig. 3a). Residues Glu210 and Glu214 in the P1 protomer B-linker interact

with Thr316 and Arg319 of the GAFTGA loop within the ATPase domain of the P4 protomer (Supplementary Fig. 3b). The same pattern is observed for the P2 and P3 protomers. The pairs of ATPase

domains within the P1/P2 and P3/P4 dimers do not interact with each other (Supplementary Fig. 3c), whereas the ATPase domains in the P1 and P2 protomers interact with those in the P3 and P4

protomers, respectively, through the twofold symmetry observed between the α-helical P1/P3 and P2/P4 subdomains (Supplementary Fig. 3d). PHENOL-BOUND SENSORY DOMAIN AND B-LINKER The sensory

domain of DmpR shows a core (β/α)4 barrel scaffold with a bound phenol and zinc ion (Fig. 3a). Each N-terminal region, comprised of residues 18–45 in each sensory domain, intertwines with

the other sensory domains to yield a tightly interlocked homodimer. The phenol is located in an enclosed cavity (24–36 Å3 in volume) formed by an antiparallel hairpin motif. The cavity is

primarily lined by hydrophobic residues, including Phe93, Trp128, Tyr155, Tyr170, and Tyr159. A strictly conserved Trp128 residue is located between the phenol-binding site and the

zinc-binding site, while the zinc is coordinated by residues Cys151, Glu172, Cys177 and Cys185 (Fig. 3b). The hydroxyl group of the phenol is located between His100 and Trp128, indicating a

ligand-positioning function of these residues. His100 is conserved in other phenol-responsive regulatory proteins, such as PoxR and MopR, while it is substituted by tyrosine in the

toluene/xylene-responsive XylR (Fig. 3c). Interestingly, the electron density of the phenol group is strong in the P1 protomer, whereas it is weak in the P2 protomer (Supplementary Fig. 4a,

b). The same pattern is also observed in the P3/P4 dimer. Given its location inside a closed pocket, the weak electron density suggests low occupation by phenol in the binding cavities of

the P2 and P4 protomers, which is associated with the altered conformations of the two protomers and the asymmetric shape of the B-linkers (see below). The B-linker connects each lobe of the

sensory and ATPase domains to form a linear helix with leucine residues at positions 212, 215, 219 and 222 creating a hydrophobic stripe on one side of the helix in the amphipathic

structure. These strips of leucine residues in the two B-linkers adopt a coiled-coil architecture in the dimer and exhibit knobs-into-holes packing typical of leucine zippers (Fig. 3d)26. At

the end of the B-linker, the helix connects to a flexible loop region consisting of residues 227–240 that has a high B-factor (~27 Å) and a sharp angle that extends into the ATPase domain

(Fig. 3e). THE ATPASE DOMAIN AND ITS TETRAMER-DEPENDENT ACTIVITY The ATPase domain consists of a typical α/β subdomain (aa 236–401) and an α-helical subdomain (aa 402–481). The GAFTGA motif

(aa 310–315) of the P1 ATPase domain is located close to the P3 sensory domain (aa 53–59) and the P4 B-linker helix (aa 209–213) (Supplementary Fig. 5a). The GAFTGA regions exhibit

conformational variation among the DmpR protomers, indicating their flexibility (Supplementary Fig. 5b). All of the ATPase domains have an overall structure similar to that of the ADP-bound

form of PspF27. Although the crystallization of DmpRΔD occurred in the presence of 3 mM AMP-PNP, no electron density corresponding to a nucleotide was observed, suggesting that the GAFTGA

conformations in this structure may reflect an inactive state that is poised to bind ATP. The putative ATP binding site (cavity volume of ~26 Å3) lies at the interface between the α/β

subdomain and the α-helical subdomain and is spatially placed so that residues Glu232 and Tyr233 from the flexible loop that connects the B-linker and the ATPase domain could potentially

interact with an ATP molecule (Supplementary Fig. 5c)28. Arg223, which is conserved in the B-linkers of aromatic-sensing DmpR-like bEBPs, is located in the proximity of the putative ATP

binding site of the adjacent protomer (Supplementary Fig. 5d). To investigate the connection between oligomerization and ATPase activity, we purified additional truncated derivatives of DmpR

(Fig. 4a). BN-PAGE analysis of these derivatives after incubation with ATP or ATPγS revealed that both the ATPase domain alone (DmpRC) and the ATPase domain attached to the B-linker

(DmpRBC) exhibited a monomeric conformation. However, the truncated protein lacking only the sensory domain (DmpRΔS) displayed a tetrameric conformation even in the absence of phenol (Fig.

4b). Similarly, SEC-MALS analysis showed a peak corresponding to a protein with a molecular weight of ~164 kDa, indicating that DmpRΔS predominantly forms tetramers in solution (Fig. 4c).

The trace band of higher molecular weight observed in BN-PAGE in DmpRΔS, but not in DmpRC, DmpRBC or DmpRWT, is likely an artefact caused by non-native self-interaction of the sensory domain

deleted DmpR protein. These results show that the ATPase domain of DmpRC alone, or when attached to the B-linker (DmpRBC), does not multimerize despite the major contribution of the ATPase

domain to tetramer formation by DmpRΔD. These findings additionally suggest the involvement of the DNA-binding domain in tetramer formation, possibly through the pairing of the DNA-binding

domains29. Next, we investigated the ATPase activity of all the DmpR derivatives to assess the correlation between oligomerization and ATPase activity. The DmpRWT and DmpRΔD proteins

exhibited ATP hydrolysis in the presence of phenol, but they exhibited only marginal ATP hydrolysis in the absence of phenol (Fig. 4d). In contrast, the monomeric DmpRC and DmpRBC

derivatives did not show any ATP hydrolysis activity, while the tetrameric DmpRΔS protein exhibited efficient ATPase activity irrespective of the addition of phenol (Fig. 4e). These results

suggest that a tetrameric configuration is essential and sufficient for the ATPase domains of DmpR to hydrolyse ATP. ALTERATION OF THE CONFORMATIONS WITHIN AN ASYMMETRIC SHAPE Conformational

changes of DmpR were revealed when the protomer structures were overlapped. Superimposition of the P1 protomer, which has a high phenol occupancy, onto that of the P2 protomer, which has a

low phenol occupancy, uncovered interesting structural features. The volume of the phenol-binding pocket in the P1 protomer was 23.59 Å3, whereas it was 36.91 Å3 in the P2 protomer due to

marginal shifts in the residues lining the pocket, including Tyr90, Phe93, His100, Val113, Phe122, Tyr159 and Phe170 (Supplementary Fig. 6a). The N-terminal region, which is involved in the

interlocking of dimers (aa 18–39), is located ~2.9 Å further away from the phenol-binding site in the P1 protomer than in the P2 protomer. The helices in the B-linker also differ, with those

from the P2 protomer adopting an orientation off-set by ~24° compared to that of the corresponding helix from the P1 protomer, and as a result, the dimer exhibits a notably asymmetric

configuration (Fig. 5a). The same pattern of conformational variation was observed in the P3/P4 dimer across the diagonal of the complex (P1/P2, r.s.m.d. = 3.7 Å, 437Cα; P1/P3, r.s.m.d. =

0.9 Å, 443Cα; and P1/P4, r.s.m.d. = 4.0 Å, 443Cα). The significant shift in the B-linker is associated with helix α6 in the sensory domain; Lys200 is involved in a charged interaction with

Glu167 in the P1 protomer at a distance of 2.4 Å, while Phe203 is shifted 1.8 Å further away from the sensory domain in the P1 protomer than in the P2 protomer. Asp206 from the P1 protomer

is involved in a charged interaction with Arg60 in the sensory domain, whereas the same residue in the P2 protomer points outside of the helix and is closer to Arg67 (Fig. 5a).

Interestingly, the position of the α6 helix exhibits significant variation among the DmpR, PoxR and MopR structures despite the high structural similarity in other regions of the sensory

domain (PoxR, r.s.m.d. = 1.1 Å, 196Cα; MopR, r.s.m.d. = 0.9 Å, 158Cα) (Supplementary Fig. 6b)11,12. Helix α6 in MopR shows a completely opposite trajectory to that observed in DmpR,

demonstrating the flexibility of this helical region among the subfamily members (Fig. 5b). The closest structural analogue of the DmpR monomer is NtrC1, which is a bEBP member of a

two-component system (_Z_ score = 28.9, r.s.m.d. = 1.7 Å for 247 Cα). Superimposition of the ATPase domains of DmpRΔD with those of inactive NtrC1 (PDB ID, 1ny5) highlights the significantly

altered orientation of their B-linkers. With respect to the ATPase domain, the cognate B-linkers are displaced by ~135˚ despite the high structural similarity of each module (B-linker,

r.s.m.d. = 1.3 Å, 21 Cα; ATPase domain, r.s.m.d. = 2.4 Å, 243 Cα) (Fig. 5c). A recent report showed that the central AAA+ domain and part of the B-linker of apo DmpR forms a homodimer with a

face-to-face orientation in the ATPase domain28. Given the head-to-head geometry of the tightly intertwined sensory domains of DmpR and the dimeric features of the coiled coil B-linker

helixes, the apo dimer of DmpR may adopt a configuration similar to that of the inactive dimer of NtrC1 or NtrX (Supplementary Fig. 6c)30,31. Overall, the spatial variation in the phenol

binding pocket, the phase shifts of the residue interactions in helix α6 and the asymmetric angle and trajectory of the B-linker of DmpR indicate propagation of structural changes and

modulation of downstream domain interactions through the B-linker upon phenol binding (Fig. 5d) (see below). INTERACTION BETWEEN TETRAMERIC DMPR AND Σ54 Activation of transcription involves

a physical interaction between the bEBP and σ54-RNAP, specifically through the N-terminus region (aa 1–56) of the σ-factor32. We examined the interaction of the ligand-bound DmpR complex

with σ54 using far-Western blotting33 (Supplementary Fig. 7a). A band corresponding to the size of the σ54 protein was detected only when DmpRWT was incubated in the presence of phenol and

ATPγS (Supplementary Fig. 7b), while the ATPase activity of DmpRWT did not change upon addition of the σ54 protein (Supplementary Fig. 7c). We next measured the interaction of DmpRWT with

the σ-factor using isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) with σ54(1–119)-CPD. The σ54(1–119)-CPD protein comprises the N-terminal residues of σ54 (aa 1–119) fused to a C-terminal cysteine

protease domain (CPD) that allowed better expression and purification (Supplementary Fig. 7d). Consistent with the far-Western data, DmpRWT interacted with the N-terminal peptide of σ54 only

in the presence of phenol and ATPγS (_K_D = ~4 μM; Supplementary Fig. 7e). The stoichiometry of the ITC binding curve (_n_ = 0.86 ± 0.022) indicates a 1:1 molar ratio for the interaction

between σ54(1–119)-CPD and tetrameric DmpRWT. To visualise the interaction of DmpR with σ54(1–119)-CPD and confirm the stoichiometry of the complex, we used single-molecule fluorescence

imaging34. In the first series of experiments, biotinylated σ54(1–119)-CPD was surface-immobilized through a biotin-streptavidin interaction, and then stepwise photobleaching signals from

σ54(1–119)-CPD bound eGFP-DmpRWT were recorded using TIRF microscopy (Fig. 6a and Supplementary Fig. 8a). The number of binding events between eGFP-DmpRWT and σ54(1–119) significantly

increased upon the addition of phenol and ATPγS (Fig. 6b and Supplementary Fig. 8b). As assessed by real-time imaging, the majority of eGFP-DmpRWT bound to σ54(1–119) exhibited four-step

bleaching under these conditions (Fig. 6c, d and Supplementary Fig. 8c). The fractions of the monomeric, dimeric and trimeric states could be attributed to the incomplete maturation of the

eGFP fluorophore22,24,25,35. These results show that when associated with phenol and ATPγS, tetrameric DmpR efficiently interacts with the σ54 peptide. As a complementary approach, we

reversed the order of the interaction by immobilizing eGFP-DmpRWT in the presence of phenol and ATPγS using biotinylated anti-GFP antibody. Cy5-labelled σ54(1–119)-CPD was then added to

assess the interaction between DmpR and the σ54(1–119) peptide and determine which oligomeric state(s) of DmpR can interact with σ54 (Fig. 6e and Supplementary Fig. 8d, e). Binding of

Cy5-labelled σ54(1–119)-CPD co-localized with surface-immobilized eGFP-DmpR, indicating a highly specific interaction. eGFP-DmpRWT binding, which was observed at a location where σ54(1–119)

was pre-bound (Fig. 6f), further revealed that tetrameric DmpR specifically interacts with the σ54(1–119) peptide (Fig. 6g). Taken together, the single-molecule data suggests that in the

presence of phenol and ATP, tetrameric DmpR binds σ54 to activate transcription by σ54-RNAP. DISCUSSION Research on the activation mechanism of DmpR has been hindered due to the ambiguity of

the oligomeric state of its transcription-promoting active form. DmpR has been widely believed to form hexamers13, primarily based on its similarity to ring-structured hexameric bEBPs such

as NtrC and PspF36,37. Although many AAA+ ATPases function as hexamers, the active oligomeric state of DmpR-like bEBPs remained unclear. Thus, the discovery of the tetrameric configuration

of DmpR and its demonstrated ability to interact with the σ54 factor provided by this study represents an important step for an increased understanding of the activation mechanism of

DmpR-like single component bEBPs. Interestingly, the GAFTGA motif loops in the ATPase domains are located some distance from one another in the tetrameric architecture of DmpR with a

perpendicular twofold symmetry, whereas the GAFTGA loops are close together in the centre of the ring-like hexamer, indicating an altered mode of binding to σ54. The interaction of the DmpR

tetramer with σ54 in a 1:1 ratio implies that the initial binding to σ54 likely occurs through a GAFTGA motif in a single ATPase domain. Such an interaction could plausibly cause a steric

hindrance in the complex to prevent further interactions or could trigger an allosteric change in the tetramer that would allow it to assume a configuration optimally poised to activate

σ54-RNAP; these two mechanistic alternatives require further investigation. Given the asymmetric configuration between two monomers in a dimer and the absence of ATP molecule in the crystal

structure, the dynamic DmpR tetramer probably undergo conformational change in the process of binding and/or hydrolyzing ATP that accompanies its interaction with σ54. The structural

features of ligand-bound DmpR exhibit remarkable similarity to those of histidine kinases (HKs), which are sensory components of the bacterial two-component system. The sensing of

environmental changes through a dimeric N-terminal domain, the shifts of the coiled-coil linker helixes in the middle of the molecule, and the modulation of ATPase activity by alterations in

the positioning and orientation of a downstream domain are all reminiscent of the internal signal relay mechanism observed in HKs2. The coiled-coil architectures of the GAF, HAMP and PAS

linker domains in HKs are known to be crucial for oligomerization, signalling and the regulation of their activity38. Although the exact mechanism of signal propagation through coiled-coil

helixes in HKs is still under debate [e.g., an axial rotation, axial tilt (scissor) or axial shift (piston) mechanism], typically, HKs exhibit two distinct structural conformations: an “off”

state that imposes conformational restraints on the downstream domains and a dynamic “on” state that releases those conformational restraints, allowing the downstream domains to carry out

ATPase functions39. Intriguingly, the helical motifs that connect to the DHp domains in HKs reportedly exhibit asymmetric conformations40, as observed in the DmpRΔD-phenol structure. Given

that the symmetric to asymmetric “flip-flop” transition within a homodimer is a well-known signal transduction mechanism in many HKs41,42,43, DmpR-like bEBPs may utilize a similar mechanism

for signal transduction upon sensing aromatics. In particular, the formation of tetramers and the constitutive ATPase activity of the DmpRΔS protein support the notion that the tightly-bound

dimeric sensory domains of the full-length protein restrain the downstream domains to prevent tetramer formation in the absence of phenol, which explains the negative regulation of activity

mediated by the sensory domain of DmpR. The tightly interlocked sensory domains, which are also observed in the PoxR and MopR structures13,15, may also be the key structural element that

would prevent hexamer formation and thus set DmpR and its homologues apart from the other typical hexameric AAA+ ATPases. In the absence of phenol, DmpR may form a dimer in such a way that

the tightly intertwined sensory domains with a head-to-head geometry impose a conformational constraint on the coiled-coil helixes to place the ATPase domains side-by-side. In this scenario,

phenol binding in the sensory domain would induce a conformational change in the ligand binding pocket followed by the shift of the flexible α6 helix at the C-terminus of the sensory domain

and a resultant change in the B-linker position. The rearrangement of the coiled-coil B-linkers within the dimer would alter the angles and interfaces of the downstream ATPase domains,

allowing the association of two dimers in a head-to-tail orientation (Fig. 5d). The observation of features common between the first (HK) and second (response regulator, e.g., NtrC) protein

that make up two-component systems suggests that DmpR may have combined the sensing and the regulation modules of each protein into one protein to ensure simple and efficient detection of

small lipophilic ligands that can freely diffuse through the membrane layer. The formation of a DmpR tetramer in the presence of phenol and the absence of ATP indicates that ATP binding and

hydrolysis, known to be prerequisites for transcriptional activation, are not required for subunit association. It thus appears plausible that ATP is bound to DmpR after oligomerization, and

the energy from ATP hydrolysis is subsequently utilized for coordinating the binding and restructuring of σ54-RNA polymerase through the structural rearrangement of the GAFTGA loop. Because

it is structurally distinct from ring-forming hexameric AAA+ bEBPs, the interaction of a tetrameric complex with σ54 represents a unique mechanistic mode of DmpR-like bEBPs in terms of

σ54-dependent transcriptional activation. METHODS CLONING AND PROTEIN PURIFICATION DNA encoding _DmpR_ (Accession No. AAP46187.1) was amplified by PCR from _Pseudomonas putida_ KCTC 1452

(Accession No. AF515710). Fragments spanning codons 1–563 (wild type), 18–481 (DmpRΔD), 205–563 (DmpRΔS), 205–481 (DmpRBC) and 232–481 (DmpRC) were cloned into the pProEX HTa vector, which

has an N-terminal His tag (Invitrogen), via the _BamH_I and _Hind_III restriction sites. The DmpR cysteine mutant (C119S/C137S) was generated using a site-directed mutagenesis kit

(Enzynomics) and verified by DNA sequencing (Solgent). The σ54 gene sequence, (accession no. WP_003255133) including the σ54 and σ54(1–119) gene cassettes, was cloned into the pET22b

expression vector via the _Nde_I/_Hind_III sites, and the CPD coding region was inserted in-frame using the _Hind_III/_Xho_I sites to generate the σ54(1–119)-CPD expression construct. The

eGFP (FPbase ID. R9NL8) gene was fused with pProEX HTa-cloned DmpR by a ligation-independent cloning method. Detailed cloning primer information is listed in Supplementary Table 1. For DmpR

purification, the His-tagged wild type, substituted, and eGFP-tagged DmpR variants were produced using _E. coli_ strain BL21-CodonPlus (DE3)-RIL (Agilent Technologies, #230245), which was

cultured at 30 °C, with expression was induced with 1 mM IPTG. The cells were harvested, lysed and centrifuged. The supernatant was then applied to a His-Trap HP column (GE Healthcare) in

elution buffer composed of 30 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 250 mM NaCl, 3 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 1 mM PMSF, 250 mM imidazole and 5% glycerol. The peak fractions were applied to a Superdex 200

Increase 10/300 column (GE Healthcare) in a final elution buffer composed of 30 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 50 mM NaCl, 3 mM β-mercaptoethanol and 5% glycerol. For σ54 purification, His-tagged

wild type σ54 and its variants were expressed as described above. The supernatants were applied to His-Trap HP columns (GE Healthcare) with elution buffer composed of 30 mM Tris-HCl (pH

7.5), 500 mM NaCl, 3 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 1 mM PMSF, 1 mM DTT, 250 mM imidazole and 5% glycerol. To remove the CPD tag, σ54-CPD protein was incubated with 1 µM phytic acid overnight at 25

°C. Peak fractions were applied to a Superdex 200 Increase 10/300 column (GE Healthcare) in a final elution buffer composed of 30 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 3 mM β-mercaptoethanol

and 5% glycerol. To add the biotin and Cy5 fluorescent dye to σ54(1–119)-CPD, purified σ54(1–119)-CPD was reduced in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with 10 mM DTT for 2 hours at 25 °C. The

reduced protein was buffer-exchanged into PBS without DTT using PD MiniTrap G-10 (GE Healthcare) and labelled with either poly(ethylene glycol) [N-(2-maleimidoethyl)carbamoyl]methyl ether

2-(biotinylamino)ethane (Sigma-Aldrich, cat# 757748) or Cy®5 Maleimide Mono-Reactive Dye (Sigma, cat# GEPA15131) for 2 hours at room temperature followed by incubation at 4 °C overnight. The

labelled σ54(1–119)-CPD preparations were then purified by SEC with a Superdex 200 10/300 GL column. The fractions containing labelled proteins were concentrated using Amicon® Ultra

Centrifugal Filters, pooled in PBS with 50% glycerol, snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C. SINGLE-MOLECULE TIRF IMAGING AND DATA ACQUISITION A prism-type total internal

reflection microscope was used for the SMPB experiments. The eGFP derivative was excited with a 473-nm laser (Coherent, OBIS LX 75 mW); Cy5 was excited using a 637-nm laser (Coherent, OBIS

637 nm LX 140 mW). To obtain time traces, eGFP was excited as weakly as possible to minimize their rapid photobleaching during the time course of a measurement. The fluorescence signals from

single molecules were collected using an inverted microscope (Olympus, IX-73) with a ×60 water immersion objective (Olympus, ULSAPO60xW). To block the 473-nm laser scattering, we used a 473

nm EdgeBasic™ best-value long-pass edge filter (Semrock, BLP01-473R-25). When the 637-nm laser was used, the 637-nm laser scattering was blocked with a notch filter (Semrock, 488/532/635

nm, NF01-488/532/635). Subsequently, the Cy5 signals were spectrally split with a dichroic mirror (Chroma, 635dcxr) and imaged with the halves of an electron multiplying EMCCD camera (Andor

Technology, iXon 897). The data were obtained in either single-colour or dual-colour mode. To eliminate the nonspecific adsorption of proteins onto the quartz surface, piranha-etched slides

(Finkenbeiner) were passivated with a mixture of mPEG-SVA (5 kDa, Lysan Bio Inc.) and Biotin-PEG-SVA (5 kDa, Lysan Bio Inc.) in the first PEGylation treatment, and then MS(PEG)4

Methyl-PEG-NHS-Ester reagent (ThermoFisher Scientific) was used for the second treatment as described previously44. To further improve the surface quality, the assembled microfluidic flow

chambers were subsequently incubated with 5% Tween-20 (v/v in T50 buffer containing 10 mM Tris, pH 8.0, and 50 mM NaCl) for 10 min45, followed by a wash step with 100 µL of T50 buffer.

Afterwards, the slides were incubated with 50 µL of streptavidin (0.1 mg/mL in T50 buffer, S888, Invitrogen) for 5 min, followed by a wash step with 100 µL of phosphate-buffered saline

(PBS). For the single-molecule photobleaching (SMPB) assay, 50 µL of 1 ng/mL anti-GFP (biotin) goat polyclonal antibody (pAb) (Abcam, ab6658) was injected into the chambers and incubated for

5 min prior to a wash step with 100 µL of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). One microlitre of 10 nM eGFP-DmpRWT was incubated with or without 1 mM MgCl2, 3 mM phenol and/or 1 mM ATP for 15

min at 30 °C in PBS as indicated. A total of 100 µL of 100-fold diluted reactant (100 pM protein with or without 1 mM MgCl2, 3 mM phenol and/or 1 mM ATP) was injected into the biotinylated

anti-GFP pAb-coated slide chamber and incubated for 5 min followed by washing with 100 µL of PBS. To observe the interaction between eGFP-DmpRWT and Cy5-labelled σ54(1-119)-CPD, anti-GFP

(biotin) goat polyclonal antibody (pAb) (Abcam, #ab6658) was injected into the chambers and incubated for 5 min prior to a wash step with 100 µL of imaging buffer [50 mM HEPES-NaOH pH 7.5,

300 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 1% dextrose monohydrate (w/v, Sigma, D9559) and 1 mM Trolox ((±)-6-Hydroxy-2,5,7,8-tetramethylchromane-2-carboxylic acid, Sigma, 238813)]. One microlitre of 10 nM

eGFP-DmpRWT was incubated with 1 mM MgCl2, 3 mM phenol, and/or 1 mM ATPγS for 30 min at 37 °C in the imaging buffer. A total of 100 µL of 100-fold diluted reactant (100 pM protein with 1 mM

MgCl2, 3 mM phenol, and 1 mM ATPγS) was injected into the biotinylated anti-GFP pAb-coated slide chamber and incubated for 5 min followed by washing with 100 µL of imaging buffer. A total of

50 µL of 1 nM Cy5-labelled σ54(1–119)-CPD was incubated in the eGFP-DmpR-coated microfluidic chamber for 5 min followed by washing with 100 µL of imaging buffer supplemented with 0.1 mg/mL

glucose oxidase (Sigma, G2133), 4 mg/ml catalase (Roche, 10106810001). A series of EMCCD images were acquired with laboratory-made software with a time resolution of 100 msec. The

fluorescence time traces were extracted with an algorithm written using IDL (ITT Visual Information Solutions) that defined the fluorescence spots according to a threshold defined by a

Gaussian profile. The extracted time traces were analysed using customized MATLAB programs (MathWorks). The counting of photobleaching steps was performed manually. Stepwise fitting lines in

the representative traces were also drawn manually using Illustrator (Adobe). STRUCTURE DETERMINATION Crystallization was conducted using the sitting-drop vapor diffusion method at 4 °C

with DmpRΔD protein (13.5 mg/ml, 1.5 µl) and an equal volume of the crystallization solution (340 mM Na/K-tartrate, 80 mM glycine, 3 mM AMP-PNP and 10 mM phenol). Before data collection, the

crystals were cryocooled to 93 K using a cryoprotectant consisting of mother liquor and 25% glycerol. The diffraction data set was collected using the MX7A synchrotron beamline at the

Pohang Accelerator Laboratory (Pohang, Korea). The crystals diffracted to a resolution of 3.4 Å, and the data were collected by 365° rotation of the crystal at 1° intervals. The diffraction

data were processed and scaled using HKL2000. The structure was determined by the molecular replacement method using the CCP4 and Phenix suite with the structures of PoxR (PDB ID, 5fru) and

NtrC1 (PDB ID, 1ny5) as search models for the sensory and ATPase domains, respectively. The model building and structure refinement were performed using the programs Wincoot and Phenix.

Molecular images were produced using Pymol. The Ramachandran statistics for the model are as follows: 94 % of the residues were in the favoured region, 5% of the residues were in the allowed

region and 1% of residues were in the outlier region. The crystallographic data that support the findings of this study (PDB ID; 6IY8) are available from the Protein Data Bank. The

crystallographic data statistics are summarized in Supplementary Table 2. MALS AND BN-PAGE MALS analysis was performed using a WTC-050S5 SEC column with an in-line Dawn Helios II system and

an Optilab T-rEX differential refractometer (Wyatt). DmpR (10 µM), phenol (1 mM) and/or ATP/ATPγS (3 mM) were incubated at 25 °C for 20 min in PBS buffer. After centrifugation, the

supernatant was applied to a SEC-MALS system with PBS elution buffer containing 0.5 mM phenol. The data were collected and analysed using ASTRA 6 (Wyatt). Gradient gels (4–16%) were used for

BN-PAGE (Novex). To identify factors that might influence the oligomer state of DmpR, 20 µM DmpR, was incubated for 20 min at 25 °C in the presence or absence of 1 mM phenol, 5 mM MgCl2

and/or 3 mM ATP, respectively. To determine change of DmpR tetramer by ATP analogue or UAS containing DNA, 3 mM ATP analogue (AMP-PNP/ATPγS), 10 nM DNaseI (NEB) or 20 µM cognate DNA with the

UAS sites were co-incubated with DmpR for 20 minutes prior to BN-PAGE analysis. SIZE EXCLUSION CHROMATOGRAPHY AND DYNAMIC LIGHT SCATTERING DmpR (20 µM) and phenol (0.5 mM) were incubated at

25 °C for 20 min in PBS buffer. After centrifugation, the supernatant was applied to a SEC or DLS system. SEC analysis was performed using a Superdex 200 increase 10/300 column with an AKTA

FPLC system (GE Healthcare). DLS analysis was performed using a Zetasizer Ultra (Malvern), fitted with a 10-mW 632.8 nm laser with scattering angle of 173° in air and set at a 90°

scattering angle. MOLECULAR DOCKING MODELLING The inactive DmpR dimer was modelled using the _A_. _aeolicus_ NtrC1 in complex with ADP (PDB ID, 1ny5) as the template. The dimeric NtrC1

structure was truncated so that only the ATPase domain was retained. The docking of ADP to the DmpRΔD structure with loop modelling was performed using the SwissDock server. The initial

models were subjected to energy minimization followed by 1 ps of molecular dynamics at 300 K after equilibration. They were finally minimized to a maximum derivative with 1.0 kcal per step

using the Discover module in the Insight II program (Accelrys) with the AMBER force field. ATPASE ASSAY The ATPase reactions were initiated by adding 5 mM MgCl2 into a mix containing 200 nM

DmpR protein, 50 µM ATP, [γ32P] ATP (5 Ci/mmol) or/and 1 mM phenol or/and 1 mM σ54 in phosphate buffed saline. The reactions (20 μl) were incubated at 25 °C for 20 min and then terminated by

the addition of 10 mM EDTA. The radiolabelled reaction products (1.5 μl) were separated with polyethyleneimine-cellulose thin-layer plates (Merck) in 0.325 M phosphate buffer (pH 3.5) and

visualised using a FLA-5100 phosphorimager (Fujifilm). ISOTHERMAL TITRATION CALORIMETRY The ITC experiments were conducted using a MicroCal Auto-iTC200 at 25 °C at the Korea Basic Science

Institute (KBSI). The DmpR solution (10 µM or 40 µM) in the calorimetric cell was titrated with the phenol ligand (100 µM), cognate DNA with specific UAS sequences (100 µM), or

σ54(1–119)-CPD protein (400 µM) as the injectant. The data were analysed with the MicroCal Origin software package (GE Healthcare). FAR-WESTERN BLOT ASSAY Purified σ54 protein (0.25 μg) was

resolved by 10% SDS-PAGE and electro-transferred onto PVDF membranes (GE Healthcare). The σ54 bound to the membrane was refolded by incubation in 6 M~0.1 M guanidine-HCl in AC buffer (10%

glycerol, 100 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris, 0.5 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT and 0.1% Tween-20) supplemented with 5% milk powder for 3 h at room temperature. Then, the membrane was washed with AC buffer

supplemented with 5% milk powder for 2 hours at 4 °C prior to incubation with 500 μg/ml His-tagged DmpR bait protein at 4 °C overnight. The membrane was subsequently washed and incubated for

1 hour with His-tag antibody (Invitrogen, #MA1-21315, 3000-fold dilutions) in phosphate-buffered saline with Tween-20 (PBST) with 3% milk powder. After washing with PBST, the membrane was

incubated for 1 hour with the anti-mouse secondary antibody (Sigma, #A3562, 30,000-fold dilutions). REPORTING SUMMARY Further information on research design is available in the Nature

Research Reporting Summary linked to this article. DATA AVAILABILITY The source data underlying Figs. 1f–j, 4b–e and 6b, d, g and Supplementary Figs. 1a–f, 2b, 7b, c, e and 8c are provided

as a Source Data file. Coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) with the accession code 6IY8. Other data are available from the corresponding

authors upon reasonable request. REFERENCES * Bush, M. & Dixon, R. The role of bacterial enhancer binding proteins as specialized activators of sigma54-dependent transcription.

_Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev._ 76, 497–529 (2012). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Gao, R. & Stock, A. M. Biological insights from structures of two-component

proteins. _Annu. Rev. Microbiol._ 63, 133–154 (2009). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Tropel, D. & van der Meer, J. R. Bacterial transcriptional regulators for

degradation pathways of aromatic compounds. _Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev._ 68, 474–500 (2004). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Park, S. M., Park, H. H., Lim, W. K.

& Shin, H. J. A new variant activator involved in the degradation of phenolic compounds from a strain of _Pseudomonas putida_. _J. Biotechnol._ 103, 227–236 (2003). Article CAS PubMed

Google Scholar * O’Neill, E., Sze, C. C. & Shingler, V. Novel effector control through modulation of a preexisting binding site of the aromatic-responsive sigma(54)-dependent

regulator DmpR. _J. Biol. Chem._ 274, 32425–32432 (1999). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Shingler, V. & Moore, T. Sensing of aromatic compounds by the DmpR transcriptional activator

of phenol-catabolizing _Pseudomonas_ sp. strain CF600. _J. Bacteriol._ 176, 1555–1560 (1994). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Fuchs, G., Boll, M. & Heider, J.

Microbial degradation of aromatic compounds—from one strategy to four. _Nat. Rev. Microbiol_ 9, 803–816 (2011). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Choi, S. L. et al. Toward a

generalized and high-throughput enzyme screening system based on artificial genetic circuits. _ACS Synth. Biol._ 3, 163–171 (2014). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Kim, H. et al. A

cell-cell communication-based screening system for novel microbes with target enzyme activities. _ACS Synth. Biol._ 5, 1231–1238 (2016). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Wise, A. A.

& Kuske, C. R. Generation of novel bacterial regulatory proteins that detect priority pollutant phenols. _Appl Environ. Microbiol._ 66, 163–169 (2000). Article CAS PubMed PubMed

Central Google Scholar * Patil, V. V., Park, K. H., Lee, S. G. & Woo, E. Structural analysis of the phenol-responsive sensory domain of the transcription activator PoxR. _Structure_

24, 624–630 (2016). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Ray, S., Gunzburg, M. J., Wilce, M., Panjikar, S. & Anand, R. Structural basis of selective aromatic pollutant sensing by the

effector binding domain of MopR, an NtrC family transcriptional regulator. _ACS Chem. Biol._ 11, 2357–2365 (2016). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Wikstrom, P., O’Neill, E., Ng, L.

C. & Shingler, V. The regulatory N-terminal region of the aromatic-responsive transcriptional activator DmpR constrains nucleotide-triggered multimerisation. _J. Mol. Biol._ 314, 971–984

(2001). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Shingler, V. Signal sensory systems that impact sigma(5)(4) -dependent transcription. _FEMS Microbiol. Rev._ 35, 425–440 (2011). Article CAS

PubMed Google Scholar * O’Neill, E., Wikstrom, P. & Shingler, V. An active role for a structured B-linker in effector control of the sigma54-dependent regulator DmpR. _EMBO J._ 20,

819–827 (2001). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Zhang, X. et al. Mechanochemical ATPases and transcriptional activation. _Mol. Microbiol._ 45, 895–903 (2002). Article CAS

PubMed Google Scholar * Shingler, V. Signal sensing by sigma 54-dependent regulators: derepression as a control mechanism. _Mol. Microbiol._ 19, 409–416 (1996). Article CAS PubMed

Google Scholar * Sze, C. C., Laurie, A. D. & Shingler, V. In vivo and in vitro effects of integration host factor at the DmpR-regulated sigma(54)-dependent Po promoter. _J. Bacteriol._

183, 2842–2851 (2001). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * O’Neill, E., Ng, L. C., Sze, C. C. & Shingler, V. Aromatic ligand binding and intramolecular signalling of

the phenol-responsive sigma54-dependent regulator DmpR. _Mol. Microbiol._ 28, 131–141 (1998). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Koh, S. et al. Molecular insights into toluene sensing in the

TodS/TodT signal transduction system. _J. Biol. Chem._ 291, 8575–8590 (2016). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Liu, L., Baase, W. A. & Matthews, B. W. Halogenated

benzenes bound within a non-polar cavity in T4 lysozyme provide examples of I…S and I…Se halogen-bonding. _J. Mol. Biol._ 385, 595–605 (2009). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar *

Ulbrich, M. H. & Isacoff, E. Y. Subunit counting in membrane-bound proteins. _Nat. Methods_ 4, 319–321 (2007). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Jain, A. et al.

Probing cellular protein complexes using single-molecule pull-down. _Nature_ 473, 484–488 (2011). Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Durisic, N., Laparra-Cuervo,

L., Sandoval-Alvarez, A., Borbely, J. S. & Lakadamyali, M. Single-molecule evaluation of fluorescent protein photoactivation efficiency using an in vivo nanotemplate. _Nat. Methods_ 11,

156–162 (2014). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Liesche, C. et al. Automated analysis of single-molecule photobleaching data by statistical modeling of spot populations. _Biophys.

J._ 109, 2352–2362 (2015). Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Eilers, M., Patel, A. B., Liu, W. & Smith, S. O. Comparison of helix interactions in membrane and

soluble alpha-bundle proteins. _Biophys. J._ 82, 2720–2736 (2002). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Rappas, M. et al. Structural insights into the activity of

enhancer-binding proteins. _Science_ 307, 1972–1975 (2005). Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Seibt, H., Sauer, U. H. & Shingler, V. The Y233 gatekeeper of

DmpR modulates effector-responsive transcriptional control of sigma(54) -RNA polymerase. _Environ. Microbiol._ 21, 1321–1330 (2019). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Yuan, H. S. et

al. The molecular structure of wild-type and a mutant Fis protein: relationship between mutational changes and recombinational enhancer function or DNA binding. _Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA_

88, 9558–9562 (1991). Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Lee, S. Y. et al. Regulation of the transcriptional activator NtrC1: structural studies of the regulatory and AAA+ ATPase

domains. _Genes Dev._ 17, 2552–2563 (2003). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Fernandez, I. et al. Three-dimensional structure of full-length NtrX, an unusual member of

the NtrC family of response regulators. _J. Mol. Biol._ 429, 1192–1212 (2017). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Yang, Y. et al. TRANSCRIPTION. Structures of the RNA

polymerase-sigma54 reveal new and conserved regulatory strategies. _Science_ 349, 882–885 (2015). Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Wu, Y., Li, Q. & Chen, X.

Z. Detecting protein-protein interactions by Far western blotting. _Nat. Protoc._ 2, 3278–3284 (2007). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Lee, H. W. et al. Real-time single-molecule

co-immunoprecipitation analyses reveal cancer-specific Ras signalling dynamics. _Nat. Commun._ 4, 1505 (2013). Article ADS PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Cranfill, P. J. et

al. Quantitative assessment of fluorescent proteins. _Nat. Methods_ 13, 557–562 (2016). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * De Carlo, S. et al. The structural basis for

regulated assembly and function of the transcriptional activator NtrC. _Genes Dev._ 20, 1485–1495 (2006). Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Joly, N. et al. Managing

membrane stress: the phage shock protein (Psp) response, from molecular mechanisms to physiology. _FEMS Microbiol. Rev._ 34, 797–827 (2010). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Gushchin

I, et al. Mechanism of transmembrane signaling by sensor histidine kinases. _Science_ 356, 6345 (2017). Article CAS Google Scholar * Gushchin, I. & Gordeliy, V. Transmembrane signal

transduction in two-component systems: piston, scissoring, or helical rotation? _Bioessays_ 40, 1700197 (2018). Article CAS Google Scholar * Bhate, M. P., Molnar, K. S., Goulian, M. &

DeGrado, W. F. Signal transduction in histidine kinases: insights from new structures. _Structure_ 23, 981–994 (2015). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Ferguson, K.

M. Structure-based view of epidermal growth factor receptor regulation. _Annu. Rev. Biophys._ 37, 353–373 (2008). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Lemmin, T., Soto, C.

S., Clinthorne, G., DeGrado, W. F. & Dal Peraro, M. Assembly of the transmembrane domain of _E. coli_ PhoQ histidine kinase: implications for signal transduction from molecular

simulations. _PLoS Comput. Biol._ 9, e1002878 (2013). Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Ferris, H. U., Coles, M., Lupas, A. N. & Hartmann, M. D.

Crystallographic snapshot of the _Escherichia coli_ EnvZ histidine kinase in an active conformation. _J. Struct. Biol._ 186, 376–379 (2014). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar *

Chandradoss, S. D. et al. Surface passivation for single-molecule protein studies. _J. Vis. Exp_. doi: 0.3791/50549 (2014). * Pan, H., Xia, Y., Qin, M., Cao, Y. & Wang, W. A simple

procedure to improve the surface passivation for single molecule fluorescence studies. _Phys. Biol._ 12, 045006 (2015). Article ADS PubMed CAS Google Scholar Download references

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This research was partly supported by the Marine Biotechnology Programme of the Korea Institute of Marine Science and Technology Promotion (KIMST), the Ministry of Oceans

and Fisheries (MOF) (No. 20170488), the National Research Fund (NRF-2018R1A2A2A05021648) and the KRIBB Research Initiative. S.-G.L. supported partly by the grant from the National Research

Foundation (2018R1A2B3004755). S.K. was partly funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie Grant Agreement No. 753528. C.J.

was funded by the Foundation for Fundamental Research on Matter (Projectruimte 15PR3188). AUTHOR INFORMATION Author notes * These authors contributed equally: Kwang-Hyun Park, Sungchul Kim.

AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Disease Target Structure Research Center, Korea Research Institute of Bioscience & Biotechnology (KRIBB), Daejeon, 305-806, Republic of Korea Kwang-Hyun Park,

Su-Jin Lee, Jee-Eun Cho, Vinod Vikas Patil, Arti Baban Dumbrepatil, Hyung-Nam Song, Woo-Chan Ahn & Eui-Jeon Woo * Kavli Institute of Nanoscience and Department of Bionanoscience, Delft

University of Technology, 2629 HZ, Delft, The Netherlands Sungchul Kim & Chirlmin Joo * Department of Proteome Structural Biology, KRIBB School of Bioscience, University of Science and

Technology (UST), Daejeon, 305-333, Republic of Korea Su-Jin Lee, Vinod Vikas Patil & Eui-Jeon Woo * Synthetic Biology and Bioengineering Research Center, Korea Research Institute of

Bioscience & Biotechnology (KRIBB), Daejeon, 305-806, Republic of Korea Seung-Goo Lee * Department of Molecular Biology, Umeå University, 90187, Umeå, SE, Sweden Victoria Shingler

Authors * Kwang-Hyun Park View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Sungchul Kim View author publications You can also search for this author

inPubMed Google Scholar * Su-Jin Lee View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Jee-Eun Cho View author publications You can also search for this

author inPubMed Google Scholar * Vinod Vikas Patil View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Arti Baban Dumbrepatil View author publications You

can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Hyung-Nam Song View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Woo-Chan Ahn View author

publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Chirlmin Joo View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Seung-Goo Lee

View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Victoria Shingler View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar

* Eui-Jeon Woo View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CONTRIBUTIONS K.-H.P., S.K. and E.-J.W. conceived the study. S.-G.L. and V.S. provided

scientific and experimental suggestions. K.-H.P., S.K., S.-J.L., J.-E.C., H.-N.S., A.B.D. and W.-C.A. performed the protein purification and/or crystallization. The structural data analysis

and refinement were performed by K.-H.P. and E.-J.W. The biochemical experiments were performed by K.-H.P., S.-J.L., V.V.P. and W.-C.A., and the single-molecule fluorescence analysis was

performed by S.K. and C.J. The manuscript was written by K.-H.P., S.K., V.S. and E.-J.W. with input from all authors. CORRESPONDING AUTHORS Correspondence to Chirlmin Joo or Eui-Jeon Woo.

ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS The authors declare no competing interests. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION PEER REVIEW INFORMATION _Nature Communications_ thanks the anonymous reviewer(s)

for their contribution to the peer reviewa of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available. PUBLISHER’S NOTE Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in

published maps and institutional affiliations. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION PEER REVIEW FILE REPORTING SUMMARY SOURCE DATA SOURCE DATA RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS OPEN

ACCESS This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format,

as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third

party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the

article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright

holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Park, KH., Kim, S., Lee, SJ. _et

al._ Tetrameric architecture of an active phenol-bound form of the AAA+ transcriptional regulator DmpR. _Nat Commun_ 11, 2728 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-16562-5 Download

citation * Received: 26 September 2019 * Accepted: 11 May 2020 * Published: 01 June 2020 * DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-16562-5 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following

link with will be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature

SharedIt content-sharing initiative