Play all audios:

ABSTRACT Hydrogeological properties can change in response to large crustal earthquakes. In particular, permeability can increase leading to coseismic changes in groundwater level and flow.

These processes, however, have not been well-characterized at regional scales because of the lack of datasets to describe water provenances before and after earthquakes. Here we use a large

data set of water stable isotope ratios (_n_ = 1150) to show that newly formed rupture systems crosscut surrounding mountain aquifers, leading to water release that causes groundwater levels

to rise (~11 m) in down-gradient aquifers after the 2016 _M__w_ 7.0 Kumamoto earthquake. Neither vertical infiltration of soil water nor the upwelling of deep fluids was the major cause of

the observed water level rise. As the Kumamoto setting is representative of volcanic aquifer systems at convergent margins where seismotectonic activity is common, our observations and

proposed model should apply more broadly. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS EARTHQUAKES AND EXTREME RAINFALL INDUCE LONG TERM PERMEABILITY ENHANCEMENT OF VOLCANIC ISLAND HYDROGEOLOGICAL

SYSTEMS Article Open access 19 November 2020 EARTHQUAKES AND VERY DEEP GROUNDWATER PERTURBATION MUTUALLY INDUCED Article Open access 01 July 2021 GEOELECTRICAL EVIDENCE OF FLUID CONTROLLING

SLOW AND REGULAR EARTHQUAKES ALONG A PLATE INTERFACE Article Open access 16 May 2025 INTRODUCTION Coseismic hydrological changes are widespread and changes in water level after earthquakes

are the most frequently documented responses1,2. Explanations for changes in water level generally fall into four categories: pore-pressure response to static elastic strain3,4, fluid

migration along seismic ruptures5,6,7,8, permeability changes caused by cracking and seismic vibrations9,10,11,12,13, and pore-pressure changes in response to liquefaction or

consolidation14,15,16. Stable isotope ratios of oxygen and hydrogen in the water molecule (δD and δ18O) have been used as a direct water fingerprinting tool to examine the changes between

before and after earthquakes10,17,18,19,20. However, these isotopic studies could not be placed in a regional context because of the lack of good spatial and temporal sampling throughout the

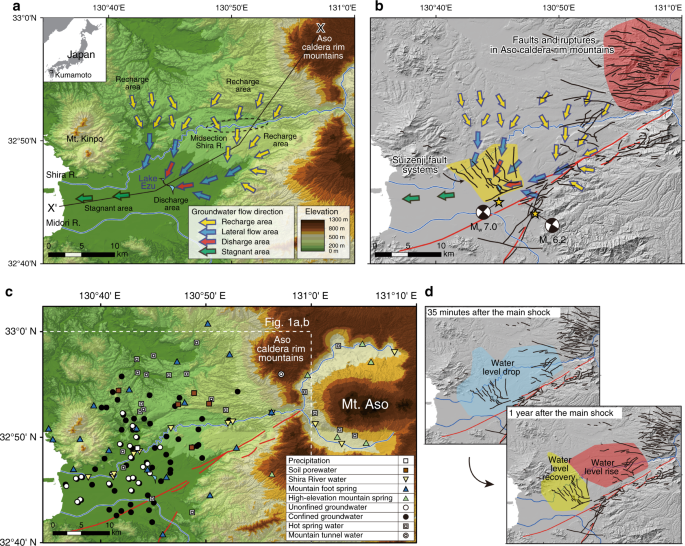

watershed. Here we use a comprehensive isotopic dataset obtained from the Kumamoto region (Fig. 1), Japan, to identify and explain subsurface hydrogeological responses to the 2016 _M__w_

7.0 Kumamoto earthquake. Groundwater flow in the Kumamoto region generally follows the topographic slope (Fig. 1a). Aquifer systems consist mainly of permeable volcanic pyroclastic deposits,

porous lavas, and alluvial deposits of Quaternary ages that overlie hydrogeological basement of relatively impermeable metasedimentary rocks and volcanic rocks of older ages21. The two

major aquifer systems, an unconfined aquifer (ca. <90 m in depth) and an underlying confined to semi-confined aquifer (ca. 20–200 m thick), are separated by an aquitard (Supplementary

Fig. 1). According to previous hydrogeological studies, groundwaters are recharged in the northern and eastern highlands at elevations of ca. 50–200 m (defined as the recharge area, Fig.

1a), then flow laterally south- and westward (lateral flow area), and mostly discharge within 40 years as springs in Lake Ezu at the entrance to the plain area (discharge

area)21,22,23,24,25. Groundwaters are recharged through soils by precipitation and by river water along the midsection of the Shira River (Fig. 1a). Some nearly stagnant groundwaters remain

in the plains and coastal regions to the west of Lake Ezu (stagnant area). Behind these regional groundwater flow systems there are mountain aquifers surrounding the Aso caldera and Kinpo

mountains (Fig. 1). These mountain waters discharge as springs both at the base of their respective mountains (defined as mountain foot springs, at elevations ca. 200 m) and at higher

elevations (high-elevation mountain springs, ca. 400–620 m). Here, the term groundwater refers to aquifer waters in the regional groundwater flow systems and is distinguished from waters in

the mountains which we refer to as mountain aquifer water or mountain spring water. The destructive inland Kumamoto earthquake sequence began with a large _M__w_ 6.2 foreshock at 21:26 JST

on 14 April 2016, followed by the _M__w_ 7.0 main shock at 01:25 JST on 16 April 2016 (Fig. 1b). The earthquake sequence involved strike-slip and normal displacement and revealed many faults

and ruptures (Fig. 1b)26,27. Groundwater level fluctuations and changes in response to the Kumamoto earthquake were documented in previous reports (see Methods)6,25. Briefly, newly

recognized normal fault systems, e.g., Suizenji faults26,27, crosscut groundwater flow systems (Fig. 1b) and led to surface water drawdown into crust deeper than the aquifers, possibly

driven by low pressure generated in open cracks (Fig. 1d)6. This water-level drop peaked within 35 min after the main shock (Supplementary Figs. 2 and 3; 4.74 m in maximum) because the

waters rapidly filled the new cracks. After this initial drop, water levels in these areas tended to recover to the original water levels (Supplementary Figs. 2 and 3). The other notable

water level change is a rise in recharge areas (Fig. 1d and Supplementary Figs. 2, 3; a maximum 2.6 m within 45 days and 4.2 m in 1 year of the main shock). In these areas, the initial water

level decrease not only recovered but increased to a level higher than the original water table6. Hydrological models based on water budgets28 that considered other possible factors that

might cause water level changes (e.g., climate and anthropogenic water extraction and recharge), revealed that the water level increase was triggered coseismically, peaked in 4–5 months, and

persisted at least 3 years after the main shock. Displacements from the Kumamoto earthquake produced extensional strain over the study area except in the eastern mountains6. Moreover, the

groundwater levels initially dropped after the main shock in both recharge and discharge areas (Fig. 1d and Supplementary Fig. 2). It is thus difficult to explain the observed water level

rise by pore-pressure increase in response to crustal strain changes6. Continuous water level increase after earthquakes has been reported elsewhere, and has been explained by increasing

contributions of new waters owing to permeability enhancement10,13,29. Further, it has been reported that the discharge rates of the Shira River increased near the mountains after the main

shock6. It is therefore possible that increased permeability in the upstream area is responsible for the observed groundwater level rise in downgradient groundwater flow systems. Previous

studies documenting coseismic water level rise in response to permeability enhancement12,29 proposed three possible new water pathways including soil porewater infiltration from the

unsaturated zone11, groundwater mixing among different aquifers through new cracks30,31,32,33, and increased contributions from aquifers sourced in the surrounding mountains10,13,33.

However, comprehensive isotopic assessment to identify these sources, including the contribution of deep fluids and liquefaction, has not yet been achieved. This present study identifies the

origin of water level changes based on isotopic fingerprinting using a large number of samples (_n_ = 1150) of all possible water sources from the regional watershed (Fig. 1c, see Methods

for sampling strategy), comparing data before and after the earthquake (e.g., Figs. 2, 3 and Supplementary Tables 1, 2). Our results are then used to discuss the processes that led to

groundwater level rise in response to the 2016 Kumamoto earthquake. RESULTS ISOTOPIC COMPOSITIONS OF WATERS BEFORE THE EARTHQUAKE Figure 2 shows the isotopic compositions of waters before

the earthquake, including precipitation, soil porewaters, river waters, springs, and groundwaters (see Fig. 1c for their sampling locations). In Fig. 2, soil porewaters obtained from

recharge areas plot slightly to the right of the local meteoric water line for the high-water season (April–September, see Methods). We thus suggest that these waters are recharged by

precipitation during the high-water season and were partly evaporated before infiltration (see evaporation trend shown by the dotted arrow in Fig. 2)23. In contrast, the samples of mountain

springs and the Shira River plot to the left of the local meteoric water line. In addition, the high-elevation mountain springs and the Shira River waters generally show more depleted

isotopic signatures than mountain foot springs (Fig. 2), reflecting their higher recharge elevations (see the altitude effect trend shown by solid arrow in Fig. 2). The isotopic compositions

of groundwater samples collected before the earthquake plot along the local meteoric line for the high-water season and within a compositional field surrounded by that of soil porewaters,

mountain spring waters, and the surface river waters (Fig. 2). These isotopic data imply that groundwaters are recharged by precipitation between April and September and could be mixture

waters of soil porewaters, mountain aquifer waters, and the Shira River waters. The isotopic signatures of waters are the same in both aquifers (Supplementary Fig. 4a) although there are

fewer samples from unconfined aquifers due to the smaller number of monitoring wells (Fig. 1c). A contribution of mountain aquifer waters to down-gradient regional groundwater flow systems

has not been documented in previous studies; our results suggest that groundwaters are recharged partially by mountain aquifer waters. Isotopic compositions of groundwaters are stable

regardless of the season, with annual variabilities of <±0.12‰ and ±0.5‰ for δ18O and δD, respectively, based on monthly samplings in groundwater discharge areas34 (_n_ = 70,

Supplementary Table 3). As expected, isotopic compositions of spring water samples did not show systematic changes due to different sampling months (Supplementary Fig. 4b). In addition,

groundwater samples collected during two different months show overlapping isotopic compositions for both aquifers (Supplementary Fig. 4c, d). However, there are some samples from the

beginning of the low-water season (October to December) with greater δ18O than those later in the low-water season (January to March) (Supplementary Fig. 4c, d). This may be due to a lack of

sufficient samples or may imply a relatively higher contribution of soil porewaters transported through preferential flow pathways in the rainy season (June and July, see Methods), as may

be typical in recharge areas35. Isotopic characterization of water prior to the earthquake enables us to assess coseismic isotopic changes and to identify the origins of waters that caused

groundwater level to rise after the main shock. ISOTOPIC COMPOSITIONS OF WATERS AFTER THE EARTHQUAKE In Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. 5, the most remarkable post-seismic isotopic changes are

observed for groundwaters: the compositional range of samples changed from wider (shown by the field surrounded by black line in Fig. 3b–d and Supplementary Fig. 5) to a more narrow range

that is more similar to mountain foot spring waters before the earthquake (most red-circle symbols plot within a field surrounded by the blue line), regardless the sampling season, aquifer

type (confined vs. unconfined), and area of aquifers (except the stagnant area; Fig. 1a). The samples of stagnant groundwaters fall into a narrow compositional field along the high-water

season local meteoric water line for both pre- and post-seismic periods. Both mountain foot and high-elevation spring waters changed in δD and δ18O toward slightly depleted compositions,

while those of river waters did not show significant changes after the earthquake (Fig. 3a). The cause of post-seismic isotopic changes for mountain springs has been discussed elsewhere36.

Isotopic compositions of the hot spring waters obtained from deep water reservoirs (180 to 1300 m below the ground surface) show a wide range (Fig. 3a) and are divided into four groups:

compositions identical to high-elevation mountain springs, soil porewaters, water with the highest δD (−36.5‰) and δ18O (−1.84‰), and waters with relatively lower δD but higher δ18O. The hot

springs for the first two groups have meteoric water origins similar to high-elevation mountain aquifers and waters that infiltrate recharge areas, respectively. The isotopic signatures of

waters for the third and fourth groups, which are located near the coast and under the northeastern recharge areas respectively, are mixtures of sea water with high δD and δ18O (≈0‰) and

deep geofluids that experienced high temperature water-rock interaction resulting in δ18O isotopic shifts towards enriched compositions leaving δD unchanged37, respectively. Here we use the

compositional field of hot spring waters of the fourth group as a proxy for typical deep fluids that may contribute to groundwater level rise after the earthquake. The compositional ranges

of data before the earthquake were used for mountain foot and high-elevation mountain springs as isotopic references for fingerprinting assessment (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. 5). Figure

3b–d and Supplementary Fig. 5 include groundwater samples collected from different seasons. To eliminate any possible seasonal effects, only samples collected in October and November when

the groundwater level is highest (ca. 3 months after the rainy season, see Methods), are shown in Supplementary Fig. 6. In addition, observed isotopic changes are cross-checked by using the

results from the other sampling campaigns during September 2015 and March 2017 when measurements were made with a different analytical device and measured by other institutions

(Supplementary Fig. 7 and Supplementary Table 2). Results of these comparisons (Supplementary Figs. 6 and 7) confirm that the observed isotopic changes were not caused by seasonal

differences, difference in sampling years, nor analytical methods. Consequently, our measurements require that there were contributions of new waters derived from different pathways than the

original hydrogeological systems. These may have caused post-seismic water levels to rise (recharge by lateral flow) and recover (lateral flow to discharge areas); see Supplementary Fig. 2.

ORIGIN OF ADDITIONAL WATER The most remarkable result of our isotopic comparisons is that the composition of groundwaters changed from resembling a mixture of multiple sources into a

composition with a signature more similar to mountain foot spring waters. Water compositions did not change towards those of soil porewaters, river waters, and deep fluids (Fig. 3b–d and

Supplementary Fig. 5). This result implies an increased contribution of water from mountain aquifers. If the seismic ruptures crosscut aquitards between the unconfined and confined aquifers

and waters from these two aquifers mixed with each other, isotope ratios should reflect that mixing. However, analyzed isotopic ratios for both aquifers generally changed toward

compositional fields that are different from average groundwater compositions (Fig. 3b–d and Supplementary Fig. 5). Continuous water level rise in recharge areas and water recovery around

the lateral flow and discharge areas are thus most simply explained by an increasing contribution of mountain aquifer waters10,13 from above the water recharge areas. This inference supports

the hypothesis derived from hydrological analyses both for surface and subsurface waters6,28 and hydrochemical signatures that suggest mixing of diluted mountain aquifer waters38. To more

precisely identify the origins of new waters from mountain aquifers, recharge elevations of mountain spring waters are characterized isotopically. Here, analyzed mountain spring waters are

classified into two types, mountain foot springs (3 to 191 m, above sea level) with relatively enriched δD (−49.2 to −42.6‰) and δ18O (−7.79 to −6.79‰) and high-elevation mountain springs

(407–620 m) with relatively depleted δD (−55.3 to −49.1‰) and δ18O (−8.76 to −7.79‰) (Figs. 2, 3). Based on previously reported regressions for determining water recharge elevation39

$${\mathrm{\delta D}} = - 0.0164\,h -39.153,$$ where δD and _h_ (m, above sea level) represent δD values of spring waters and their recharge elevations, respectively, the recharge elevations

for each type of spring are estimated as ca. 210–613 m and ca. 607–985 m, respectively (Fig. 4a). Figure 3b–d shows that isotopic compositions of almost all groundwaters after the

earthquake approach those of mountain foot springs with intermediate recharge elevations (210–613 m) on the western Aso caldera rim and Mt. Kinpo. Recent analyses using chemical38 and

microbiological tracers40 have detected in some localized areas an increased contribution of soil porewaters, river waters, and deep fluids after the 2016 Kumamoto earthquake. For instance,

analysis of a long-term chemical monitoring dataset revealed post-seismic NO3− increase in groundwaters in recharge areas that is attributed to enhanced percolation of soil porewaters into

aquifers from agricultural fields triggered by seismic vibrations38. The same study also revealed a post-seismic increase in the contribution of deep fluids to surface aquifers based on

geochemical tracers, in particular Cl−, SO42−, and B, as has been documented in many other instances41,42,43,44,45,46. This phenomenon occurs near the epicentre of earthquakes and in

geothermal regions38. In addition, the microbiology in aquifer waters dramatically changed after the earthquake with increased exogenous microorganisms found in deep groundwaters40 such as

_Propionibacterium acnes_, which originally inhabited the surface environment. Mixing of river waters into deeper aquifer systems is thus likely. These hydrochemical and microbial anomalies

continued for at least 2 years after the earthquake. However, these effects are not reflected in a change of groundwater isotopic compositions. Thus, their contributions are negligible in

terms of water volume and unlikely to cause the observed groundwater level rise and recovery in regional groundwater flow systems, except for the river water contribution that will be

discussed later. DISCUSSION Detailed descriptions of newly recognized surface ruptures (Fig. 1b)26 showed that the formation of the Suizenji fault systems (Fig. 1b) played an important role

in inducing groundwater drawdown immediately after the earthquake (Fig. 4b) prior to the subsequent water level rise6. Similar concentrated rupture systems are present in the eastern caldera

rim mountains (Fig. 1b), and these may provide the pathways to enhance flow from mountain aquifers to downslope groundwater systems after the earthquake13. This hypothesis is consistent

with the observation that some springs in the mountains became dry after the earthquake36. However, the high-elevation mountain springs and the sample of mountain aquifer water directly

obtained from ongoing tunnel construction under caldera rim mountains (see Fig. 1c for its location), are not isotopically identical to the hypothesized additional waters (Fig. 3b–d).

Rather, our isotopic analysis suggests that fracture systems near the base of the western Aso caldera rim and Mt. Kinpo, were the dominant pathways for new waters from mountain aquifers

(Fig. 4c). The water redistribution from mountains to downslope aquifers identified by isotopic fingerprinting is most obvious in the eastern recharge area (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Fig. 8)

where the most significant abnormal water level rise was observed (Supplementary Figs. 2 and 3): isotopic compositions of groundwaters changed after the earthquake towards the compositional

field of mountain foot spring waters in the vicinity of this area, suggesting that mountain water was released and mixed with aquifer waters in the recharge areas. Moreover, mountain foot

spring waters changed their isotopic compositions to more depleted values (Supplementary Fig. 8), implying a contribution of mountain waters with higher elevations (Fig. 4c). This is further

evidence of permeability enhancement of mountain aquifers. The response of mountain waters appeared within 1 day as increased river and spring discharges6,47 and abnormal groundwater level

rise in recharge area (Supplementary Fig. 3). The water levels in this area continuously rose (Supplementary Figs. 2, 3) and peaked 4–5 months after the main shock with a maximum abnormal

water level rise of ~11 m28. In general, the recharge areas consist of major groundwater reservoirs in Kumamoto, locally called groundwater pools (Fig. 4a), and have the highest seasonal

water level fluctuations of up to ~10 m25. Thus, a large volume of coseismically-released mountain waters can be transferred to those groundwater pools in the recharge area. The isotopic

results (Fig. 3d) further suggest that water in the groundwater pools was then transported down slope and led to water level recovery by lateral flow to recharge areas over the course of the

annual hydrologic cycle (Supplementary Fig. 2). This isotopic constraint requires a faster flow than that suggested by water residence times of a few to a few tens of years estimated by

chemical age tracers25. Aquifers in recharge and discharge areas, and partly in lateral flow areas, may also have experienced permeability enhancement from the formation of rupture systems

(Fig. 1b)26. Previous studies identified faster flow only during heavy rain35. We can therefore assume that the lowered water levels due to coseismic groundwater drawdown recovered by the

contribution of large amounts of mountain waters (ca. 108 m3)47 that were transported through these preferential subsurface pathways. A few groundwater samples collected within this fault

zone changed their isotopic compositions toward those of Shira River water samples (Supplementary Fig. 9). Although such signals are the exception to the general trend, they imply that the

surface waters could travel along preferential pathways, explaining the decline of Shira River water levels near the fault zone during the first 12 h of the main shock6 and may have

partially contributed to subsequent water level recovery. Significant isotopic alterations were not observed for the waters in stagnant areas (Supplementary Fig. 5b). Some wells in

unconfined aquifers in these areas showed coseismic water level rise immediately after the main shock (Supplementary Fig. 2), which has been attributed to pore-pressure increase in response

to liquefaction (Fig. 4b)6. Vertical water mixing within these aquifer systems will not cause isotopic compositional changes. Our large isotopic datasets, covering the time before and after

the earthquake, allow us to elucidate the origins and processes of post-seismic groundwater level rise and recovery that are caused by water release from mountain aquifers triggered by

permeability enhancement after the 2016 Kumamoto earthquake. With these findings and previous work describing a short-lived initial water level drop6, we identify two major stages of

coseismic regional changes (Fig. 4). First, surface waters and groundwaters dropped (4.74 m maximum) immediately (within 35 min) after the main shock along newly formed cracks in Suizenji

fault systems (Fig. 4b). Second, water levels rose in recharge areas in response to mountain waters being released from mid-elevation areas by permeability enhancement. This water flowed to

discharge areas through preferential pathways leading to subsequent water level recovery around the Suizenji fault area (Fig. 4c). Numerical simulations involving permeability changes have

reproduced these regional flow changes using a physically-based integrated watershed modeling tool47. In recharge areas, water level rise anomalies still remain 3 years after the main shock,

hypothesized to be because of persistent permeability increase in mountain aquifers. However, further downslope, water levels almost recovered over the annual hydrological cycle by lateral

flow to discharge areas. The results of this study provide a hydrogeological framework to understand other environmental changes including water temparature48, chemistry38, microbiology40,

and water supply security49. This study illustrates how large crustal earthquakes may alter regional hydrological systems hosted in rocks of volcanic origin. Their often high permeability

and storage lead to widespread use for groundwater supplies. Global geographic overlap between volcanic and seismotectonic activity suggests that similar coseismic hydrological changes can

be anticipated in volcanic arcs worldwide. METHODS HYDROGEOLOGICAL SETTING Kumamoto has a humid monsoon-dominated climate and shows four distinct seasons

(http://www.data.jma.go.jp/gmd/cpd/longfcst/en/tourist.html). The annual average precipitation in the Kumamoto and Aso areas are 1.99 and 2.83 m y−1 with average temperatures of 16.9 and

12.9 °C, respectively (data sources: 1980–2010, http://www.jma.go.jp/jma/menu/report.html for Kumamoto; 1981–2010, https://weather.time-j.net/Climate/Chart/asootohime for Aso). In Kumamoto,

~75% of annual precipitation occurs from April through September (we call this season the high-water season), while the remaining 25% occurs from October through March (low-water season).

The rainy season (June and July) accounts for about 40% of the total annual precipitation. The Kumamoto groundwater area is bounded by the Shira River watershed to the north, the Midori

River to the south, the outer rim of Aso caldera (highest peak: 1154 m) to the east, and the Ariake Sea and Kinpo Mountain (665 m) to the west (Fig. 1a)21. The Aso caldera watershed (380

km2) is hosted within a large caldera (25 × 18 km, Fig. 1c). The ring-shape caldera rim forms the watershed divide and the central volcanic mountains (highest peak: 1592 m) are situated in

the central part of the caldera (Fig. 1c). The groundwater flow systems are briefly described in the main text. More detailed topography, geology, hydrology, seismotectonics, and sociology

are provided in refs. 6,21,25,50. In addition, detailed groundwater fluctuations with and without seismic effects, evaluations of post-seismic water level changes considering these water

level fluctuations, and changes in ground level induced by the earthquake are documented in previous studies6,25,28. In general, groundwater levels show seasonal changes and are the lowest

during April and May, and highest during October around 3 months after the rainy season. The water level changes within 45 days after the main shock (Supplementary Figs. 2, 3) can be

regarded as co-seismic changes because seasonal fluctuations are much smaller than observed water level changes during April and May 2016 (Hosono et al.6). It has been reported that

liquefaction occurred predominantly in the plains and coastal areas51 where near-stagnant groundwaters are found (Fig. 1a) in soft marine clay sediments (generally ~60 m thickness). In these

areas, water level rose immediately after the main shock for some wells in unconfined aquifers (Supplementary Fig. 2). SAMPLES A total of 872 samples were collected for isotopic analysis

and characterized for hydrological systems before the earthquake (see Fig. 1c for their sampling locations): 135 monthly precipitation samples during 2005 and 2016 (Okumura et al.23), 500

soil porewater samples from five borehole cores from the unsaturated zone in the recharge area during 2012–2014 (Okumura et al.23), 15 surface water samples from the Shira River during April

2011 and July 2011, 45 mountain spring water samples during April 2011 and July 2011 (Ide et al.36), 43 unconfined groundwater samples from municipal and national monitoring wells (the same

wells or at the same locations where water levels are monitored) during November 2009 and November 2011, and 134 confined groundwater samples from municipal and national monitoring wells

during November 2009 and November 2011. All stable isotope datasets with their sampling locations and dates are provided in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2 except for precipitation and soil

porewater data which have been provided in a previous study23. Precipitation samples were collected on the roof of Kumamoto University’s building and data were used to define the local

meteoric line (e.g., Fig. 2). In general, vertical soil porewater profiles (measured at 10 cm intervals in cores) display isotopic fractionations reflecting seasonal variability in

precipitation23. Therefore, average values for the top 10 m (100 samples for each core) were plotted for five cores in Fig. 2 as a proxy of recharge waters in the recharge areas (Fig. 1c).

All river, spring, and groundwater samples are the same samples used for other isotopic and geochemical measurements in previously published articles21,52,53,54. In total, 201 river, spring,

and groundwater samples were collected after the main shock during June 2016 and December 2017 at the same sampling sites where samples had been collected before the earthquake: the river

waters (_n_ = 11) were sampled in August 2016 to April 2017, the spring water samples (_n_ = 30) were collected in October 2016 and March–May 2017 (Ide et al.36), whereas the groundwaters

(_n_ = 160) were sampled during four campaigns in June-August 2016, October–November 2016, March–May 2017, and November–December 2017. In addition, 23 hot spring water samples were collected

over the study area from 180 to 1300 m deep boreholes in July–August 2018 to test for the possibility of deep fluids contributing to the water level changes. One mountain spring water

sample from ongoing tunnel construction (182 m below ground surface, 582 m above sea level) was also collected in October 2017 (Fig. 1c)36. ANALYTICAL PROCEDURES All samples except soil

porewaters were collected on-site and stored in a 20-ml glass vials, whereas soil porewaters were sampled in the laboratory after extraction from core soils by centrifugation under pF = 4.2

(Okumura et al.23). All sample vials were tightly capped and stored in the dark and at room temperature. Hydrogen and oxygen stable isotope ratios were determined by a continuous-flow

gas-ratio mass spectrometer at the Kumamoto University (Delta V Advantage, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). Based on replicate measurements of standards and samples, the analytical precisions

(standard deviations) for δD and δ18O were better than ±0.5‰ and ±0.05‰, respectively. Both isotope ratios are expressed in delta notation (δ) in per mill unit (‰) with respect to

international standards of Vienna Standard Mean Ocean Water. Observed coseismic isotopic changes are cross-checked by the results from the other sampling campaigns and with data analyzed

with another analytical machine. Groundwater samples were collected three times from the study area during September 2015, August 2016, and March 2017. Collected samples were analyzed for δD

and δ18O using cavity ring-down spectroscopy (Piccaro, L2120i and L2130i) installed at the Research Institute for Humanity and Nature, Japan. The analytical precisions of δD and δ18O for

this instrument are better than ±0.5‰ and ±0.1‰, respectively. Sampling locations and analyzed data are shown in Supplementary Fig. 10 and Supplementary Table 2, respectively. DATA

AVAILABILITY All isotopic data presented in Figs. 2 and 3 and Supplementary Figs. 4, 5, 6, 8b, and 9b are included in this article as Supplementary Table 1, except those for precipitation

and soil porewater samples whose data are provided in Okumura et al.23. Source data used for illustrating Supplementary Figs. 7 and 10 are listed in Supplementary Table 2. Groundwater level

data shown in Supplementary Figs. 2 and 3 are listed in Hosono et al.6. Additional information is available from the corresponding author upon resonable request. REFERENCES * Montgomery, D.

R. & Manga, M. Streamflow and water well responses to earthquakes. _Science_ 300, 2047–2049 (2003). Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Wang, C. -Y. & Manga, M. _Earthquakes

and Water_ (Springer, 2009). * Jónsson, S., Segall, P., Pedersen, R. & Björnsson, G. Post-earthquake ground movements correlated to pore-pressure transients. _Nature_ 424, 179–183

(2003). Article ADS PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Wakita, H. Water wells as possible indicators of tectonic strain. _Science_ 189, 553–555 (1975). Article ADS CAS PubMed Google

Scholar * Tsunogai, U. & Wakita, H. Precursory chemical changes in ground water: Kobe earthquake, Japan. _Science_ 269, 61–63 (1995). Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar *

Hosono, T. et al. Coseismic groundwater drawdown along crustal ruptures during the 2016 _M_ _w_ 7.0 Kumamoto earthquake. _Water Resour. Res._ 55, 5891–5903 (2019). Article ADS Google

Scholar * Sibson, R. H. & Rowland, J. V. Stress, fluid pressure and structural permeability in seismogenic crust, North Island, New Zealand. _Geophys. J. Int._ 154, 584–594 (2003).

Article ADS Google Scholar * Wang, C.-Y., Dreger, D., Manga, M. & Wong, A. Streamflow increase due to rupturing of hydrothermal reservoirs: evidence from the 2003 San Simeon,

California, earthquake. _Geophy. Res. Lett._ 31, L10502 (2004). Article ADS Google Scholar * Elkhoury, J. E., Brodsky, E. E. & Agnew, D. C. Seismic waves increase permeability.

_Nature_ 441, 1135–1138 (2006). Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Wang, C.-Y. & Manga, M. New streams and springs after the 2014 _M_ _w_ 6.0 South Napa earthquake. _Nat.

Commun._ 6, 7597 (2015). Article ADS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Mohr, C. H., Manga, M., Wang, C.-Y. & Korup, O. Regional changes in streamflow after a megathrust

earthquake. _Earth Planet. Sci. Lett._ 458, 418–428 (2017). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Rojstaczer, S., Wolf, S. & Michel, R. Permeability enhancement in the shallow crust as a

cause of earthquake-induced hydrological processes. _Nature_ 373, 237–239 (1995). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Wang, C.-Y., Wang, C. H. & Manga, M. Coseismic release of water

from mountains: Evidence from the 1999 (_M_ _w_ = 7.5) Chi-Chi earthquake. _Geology_ 32, 769–772 (2004). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Manga, M., Brodsky, E. E. & Boone, M.

Response of streamflow to multiple earthquakes. _Geophy. Res. Lett._ 30, 18 (2003). Article ADS Google Scholar * Montgomery, D. R., Greenberg, H. M. & Smith, D. T. Streamflow response

to the Nisqually earthquake. _Earth Planet. Sci. Lett._ 209, 19–28 (2003). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Wang, C.-Y., Cheng, L.-H., Chin, C.-V. & Yu, S.-B. Coseismic hydrologic

response of an alluvial fan to the 1999 Chi-Chi earthquake, Taiwan. _Geology_ 29, 831–834 (2001). Article ADS Google Scholar * Manga, M. & Rowland, J. C. Response of Alum Rock springs

to the October 30, 2007 Alum Rock earthquake and implications for the origin of increased discharge after earthquakes. _Geofluids_ 9, 237–250 (2009). Article CAS Google Scholar * Onda,

S. et al. Groundwater oxygen isotope anomaly before the M6.6 Tottori earthquake in Southwest Japan. _Sci. Rep._ 8, 4800 (2018). Article ADS PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar *

Skelton, A. et al. Changes in groundwater chemistry before two consecutive earthquakes in Iceland. _Nat. Geosci._ 7, 752–756 (2014). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Wang, C.-H., Wang,

C.-Y., Kuo, C.-H. & Chen, W.-F. Some isotopic and hydrological changes associated with the 1999 Chi-Chi earthquake, Taiwan. _Isl. Arc_ 14, 37–54 (2005). Article Google Scholar *

Hosono, T. et al. The use of δ15N and δ18O tracers with an understanding of groundwater flow dynamics for evaluating the origins and attenuation mechanisms of nitrate pollution. _Water Res._

47, 2661–2675 (2013). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Taniguchi, M., Shimada, J. & Uemura, T. Transient effects of surface temperature and groundwater flow on subsurface

temperature in Kumamoto Plain. _Jpn Phys. Chem. Earth_ 28, 477–486 (2003). Article Google Scholar * Okumura, A., Hosono, T., Boateng, D. & Shimada, J. Evaluations of soil water

downward movement velocity in unsaturated zone at groundwater recharge area using δ18O tracer: kumamoto region, southern Japan. _Geol. Croat._ 71, 65–82 (2018). Article CAS Google Scholar

* Ono, M., Tokunaga, T., Shimada, J. & Ichiyanagi, K. Application of continuous 222Rn monitor with dual loop system in a small lake. _Groundwater_ 51, 706–713 (2013). Article CAS

Google Scholar * Kagabu, M., Matsunaga, M., Ide, K., Momoshima, N. & Shimada, J. Groundwater age determination using 85Kr and multiple age tracers (SF6, CFCs, and 3H) to elucidate

regional groundwater flow systems. _J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud._ 12, 165–180 (2017). Article Google Scholar * Fujiwara, S. et al. Small-displacement linear surface ruptures of the 2016 Kumamoto

earthquake sequence detected by ALOS-2 SAR interferometry. _Earth Planets Space_ 68, 160 (2016). Article ADS Google Scholar * Goto, G., Tsutsumi, H., Toda, S. & Kumahara, Y.

Geomorphic features of surface ruptures associated with the 2016 Kumamoto earthquake in and around the downtown of Kumamoto City, and implications on triggered slip along active faults.

_Earth Planets Space_ 69, 26 (2017). Article ADS Google Scholar * Kagabu, M., Ide, K., Hosono, T., Nakagawa, K. & Shimada, J. Describing coseismic groundwater level rise using tank

model in volcanic aquifers, Kumamoto, southern Japan. _J. Hydrol._ 582, 124464 (2020). Article Google Scholar * Rojstaczer, S. & Wolf, S. Permeability changes associated with large

earthquakes: an example from Loma Prieta, California. _Geology_ 20, 211–214 (1992). Article ADS Google Scholar * Charmoille, A., Fabbri, O., Mudry, J., Guglielmi, Y. & Bertrand, C.

Post-seismic permeability change in a shallow fractured aquifer following a ML 5.1 earthquake (Fourbanne karst aquifer, Jura outermost thrust unit, eastern France). _Geophys. Res. Lett._ 32,

L18406 (2005). Article ADS Google Scholar * Tokunaga, T. Modeling of earthquake-induced hydrological changes and possible permeability enhancement due to the 17 January 1995 Kobe

Earthquake, Japan. _J. Hydrol._ 223, 221–229 (1999). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Wang, C.-Y., Liao, X., Wang, L.-P., Wang, C.-H. & Manga, M. Large earthquakes create vertical

permeability by breaching aquitards. _Water Resour. Res._ 52, 5923–5937 (2016). Article ADS Google Scholar * Sato, T., Sakai, R., Furuya, K. & Kodama, T. Coseismic spring flow changes

associated with the 1995 Kobe earthquake. _Geophys. Res. Lett._ 27, 1219–1222 (2000). Article ADS Google Scholar * Ono, M., Shimada, J., Ichikawa, T. & Tokunaga, T. Evaluation of

groundwater discharge in Lake Ezu, Kumamoto, based on radon in water. _Jpn J. Limnol._ 72, 193–210 (2011). Article CAS Google Scholar * Kawagoshi, Y. et al. Understanding nitrate

contamination based on the relationship between changes in groundwater levels and changes in water quality with precipitation fluctuations. _Sci. Total Environ._ 657, 146–153 (2019). Article

ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Ide, K. et al. Changes of groundwater flow systems after the 2016 _M_ _w_ 7.0 Kumamoto earthquake deduced by stable isotopic and CFC-12 compositions of

natural springs. _J. Hydrol._ 583, 124551 (2020). Article CAS Google Scholar * Giggenbach, W. F. Isotopic shifts in waters from geothermal and volcanic systems along convergent plate

boundaries and their origin. _Earth Planet. Sci. Lett._ 113, 495–510 (1992). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Hosono, T. & Masaki, Y. Post-seismic hydrochemical changes in regional

groundwater flow systems in response to the 2016 _M_ _w_ 7.0 Kumamoto earthquake. _J. Hydrol._ 580, 124340 (2020). Article CAS Google Scholar * Kagabu, M., Shimada, J., Shimano, Y.,

Higuchi, S. & Noda, S. Groundwater flow system in Aso caldera. _J. Jpn Assoc. Hydrol. Sci._ 41, 1–17 (2011) Google Scholar * Morimura, S., Zeng, X., Noboru, N. & Hosono, T. Changes

to the microbial communities within groundwater in response to a large crustal earthquake in Kumamoto, southern Japan. _J. Hydrol._ 581, 124341 (2020). Article Google Scholar * Barberio,

M. D., Barbieri, M., Billi, A., Doglioni, C. & Petitta, M. Hydrogeochemical changes before and during the 2016 Amatrice-Norcia seismic sequence (central Italy). _Sci. Rep._ 7, 11735

(2017). Article ADS PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Nishio, Y., Okamura, K., Tanimizu, M., Ishikawa, T. & Sano, Y. Lithium and strontium isotopic systematics of waters

around Ontake volcano, Japan: Implications for deep-seated fluids and earthquake swarms. _Earth Planet. Sci. Lett._ 297, 567–576 (2010). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Okuyama, Y.,

Funatsu, T., Fujii, T., Takamoto, N. & Tosha, T. Mid-crustal fluid related to the Matsushiro earthquake swarm (1965–1967) in northern Central Japan: Geochemical reproduction.

_Tectonophysics_ 679, 61–72 (2016). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Muir-Wood, R. & King, G. C. P. Hydrological signatures of earthquake strain. _J. Geophys. Res._ 98, 22035–22068

(1993). Article ADS Google Scholar * Hosono, T. et al. Earthquake-induced structural deformations enhance long-term solute fluxes from active volcanic systems. _Sci. Rep._ 8, 14809

(2018). Article ADS PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Wang, C.-Y., Wang, L.-P., Manga, M., Wang, C.-H. & Chen, C.-H. Basin-scale transport of heat and fluid induced by

earthquakes. _Geophys. Res. Lett._ 40, 3893–3897 (2013). Article ADS Google Scholar * Tawara, Y., Hosono, T., Fukuoka, Y., Yoshida, T. & Shimada, J. Quantitative assessment of the

changes in regional water flow systems caused by the 2016 Kumamoto Earthquake using numerical modeling. _J. Hydrol._ 583, 124559 (2020). Article Google Scholar * Miyakoshi, A. et al.

Identification of changes in subsurface temperature and groundwater flow after the 2016 Kumamoto earthquake using long-term well temperature–depth profiles. _J. Hydrol._ 582, 124530 (2020).

Article Google Scholar * Hosono, T., Saltalippi, C., Jean, J.-S. Coseismic hydro-environmental changes: insights from recent earthquakes. _J. Hydrol._ 585, 124799 (2020). Article Google

Scholar * Taniguchi, M. et al. Recovery of lost nexus synergy via payment for environmental services in Kumamoto, Japan. Front. _Environ. Sci._ 7, 28 (2019). Google Scholar * Wakamatsu,

K., Senna, S. & Ozawa, K. Liquefaction and its Characteristics during the 2016 Kumamoto Earthquake. _J. Jpn Assoc. Earthq. Eng._ 17, 81–100 (2017). Google Scholar * Hossain, S., Hosono,

T., Ide, K., Matsunaga, M. & Shimada, J. Redox processes and occurrence of arsenic in a volcanic aquifer system of Kumamoto Area, Japan. _Environ. Earth Sci._ 75, 740 (2016). Article

CAS Google Scholar * Hossain, S., Hosono, T., Yang, H. & Shimada, J. Geochemical processes controlling fluoride enrichment in groundwater at the western part of Kumamoto area, Japan.

_Water Air Soil Pollut._ 227, 385 (2016). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Hosono, T., Tokunaga, T., Tsushima, A. & Shimada, J. Combined use of δ13C, δ15N, and δ34S tracers to study

anaerobic bacterial processes in groundwater flow systems. _Water Res._ 54, 284–296 (2014). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Clark, I. D. & Fritz, P. _Environmental Isotopes in

Hydrogeology_ (Lewis Publishers, 1997). * Fritz, P. & Fontes, J. C. H. _Handbook of Environmental Isotope_ (Chemistry Elsevier Scientific Publishing Co., 1980). * Gat, J. R. &

Gonfiantini, R. _Stable Isotope Hydrology: Deuterium and Oxygen-18 in the Water Cycle, IAEA Technical Report Series #210_, _Vienna_, p. 337 (1981). Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The

government office of Kumamoto City, Kumamoto City Waterworks and Sewerage Bureau, Kumamoto Prefecture, and Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism kindly supplied

opportunities for water samplings. Dr. H. Nakata, Dr. J. Shimada, Dr. K. Ichiyanagi, Dr. K. Ide, Mr. T. Tokunaga, Mr. K. Fukamizu, Mr. N. Sugimoto, Ms. E. Ishii, and Ms. M. Hashimoto helped

us for sampling, discussion and analyzing the water stable isotope ratios. T.H. was supported by the 2016 JST J-Rapid Program (leader, Dr. H. Nakata, Kumamoto University), JSPS Grant-in-Aid

for Scientific Research B (17H01861), JSPS Fostering Joint International Research A (19KK0291) and SUNTORY Kumamoto groundwater research project. T.H. wishes to thank working group members

of Japanese Association for Groundwater Hydrology for fruitful discussion. M.T. was supported by the JSPS Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research C (17K00527), Kwansei Gakuin University Joint

Research in 2016, and Joint Research Grant for the Environmental Isotope Study of Research Institute for Humanity and Nature for isotopic analysis. M.M. and C.Y.W. were supported by the US

National Science Foundation 1615203. AUTHOR INFORMATION AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Faculty of Advanced Science and Technology, Kumamoto University, 2-39-1 Kurokami, Kumamoto, 860-8555, Japan

Takahiro Hosono * International Research Organization for Advanced Science and Technology, Kumamoto University, 2-39-1 Kurokami, Kumamoto, 860-8555, Japan Takahiro Hosono * Department of

Earth Science, Faculty of Science, Kumamoto University, 2-39-1 Kurokami, Kumamoto, 860-8555, Japan Chisato Yamada * Department of Earth and Planetary Science, University of California,

Berkeley McCone Hall, Berkeley, CA, USA Michael Manga & Chi-Yuen Wang * School of Science and Technology, Kwansei Gakuin University, 2-1 Gakuen, Sanda, 669-1337, Japan Masaharu Tanimizu

Authors * Takahiro Hosono View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Chisato Yamada View author publications You can also search for this author

inPubMed Google Scholar * Michael Manga View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Chi-Yuen Wang View author publications You can also search for

this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Masaharu Tanimizu View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CONTRIBUTIONS T.H. conceived the idea and wrote

the manuscript; C.Y. and M.T. analyzed hydrogen and oxygen isotope ratios; M.M. and C.Y.W. deepened discussions and writings. CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to Takahiro Hosono. ETHICS

DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS The authors declare no competing interests. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION PEER REVIEW INFORMATION _Nature Communications_ thanks Christoff Andermann, Alasdair

Skelton and the other anonymous reviewer for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available. PUBLISHER’S NOTE Springer Nature remains neutral with

regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION PEER REVIEW FILE RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS OPEN ACCESS This

article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as

you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party

material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s

Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Hosono, T., Yamada, C., Manga, M. _et al._

Stable isotopes show that earthquakes enhance permeability and release water from mountains. _Nat Commun_ 11, 2776 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-16604-y Download citation *

Received: 20 September 2019 * Accepted: 06 May 2020 * Published: 02 June 2020 * DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-16604-y SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with

will be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt

content-sharing initiative