Play all audios:

ABSTRACT Intuition suggests that an object should carry all of its physical properties. However, a quantum object may not act in such a manner—it can temporarily leave some of its physical

properties where it never appears. This phenomenon is known as the quantum Cheshire cat effect. It has been proposed that a quantum object can even permanently discard a physical property

and obtain a new one it did not initially have. Here, we observe this effect experimentally by casting non-unitary imaginary-time evolution on a photonic cluster state to extract weak

values, which reveals the counterintuitive phenomenon that two photons exchange their spins without classically meeting each other. A phenomenon presenting only in the quantum realm, our

results are in stark contrast with the perception of inseparability between objects and properties, and shed new light on comprehension of the ontology of observables. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING

VIEWED BY OTHERS EXPERIMENTAL DEMONSTRATION OF SEPARATING THE WAVE‒PARTICLE DUALITY OF A SINGLE PHOTON WITH THE QUANTUM CHESHIRE CAT Article Open access 05 January 2023 A STRONG NO-GO

THEOREM ON THE WIGNER’S FRIEND PARADOX Article 17 August 2020 QUANTUM CAUSALITY EMERGING IN A DELAYED-CHOICE QUANTUM CHESHIRE CAT EXPERIMENT WITH NEUTRONS Article Open access 08 March 2023

INTRODUCTION Quantum paradoxes1, which exhibit counterintuitive phenomena, have provided multiple perspectives in study of the fundamentals of quantum mechanics, from Bell non-locality2,

quantum contextuality3 to macro-realism4. Recently, the quantum Cheshire cat Gedankenexperiment, presented by Aharonov et al.5, illustrated the counterintuitive phenomenon that a physical

property can be disembodied from its physical carrier, akin to the scene A grin without a cat in the story Alice in Wonderland6. In the context of quantum Cheshire cat, the possibility of

isolating an object from its physical properties7 has sparked the interest of theoretical physicists. Soon after, extensions and further discussions of more general scenarios were

presented8,9,10,11,12. Also, the effect of quantum Cheshire cat has been found to have intrinsic links to other quantum paradoxes: for instance, the three-box paradox13. In principle,

experimental observation of the quantum Cheshire cat effect can be implemented in following perspectives: first, because the physical property is isolated from its carrier, changes in that

property should not affect the evolution of the carrier, provided that the final quantum interference is not disturbed. Second, if one have the ability to measure the “cat” and “grin”

observables, the effect can also be deduced from the measured values. With the help of significant advances in weak measurement techniques achieved in various quantum systems, experimental

observation of the quantum Cheshire cat effect has been presented in neutronic14 and photonic system15. However, while these observations were based on true quantum objects (i.e., single

neutrons or photons), the results do not strictly support the unique quantum character of the cat, because completely identical phenomena can be observed with classical light16. Although it

is commonly accepted that quantum interference plays a crucial role in the quantum Cheshire cat effect17, experiments involving only the first-order interference cannot resolve the question

of whether, in the sense of quantum mechanics, the grin of the “Cheshire cat” is left behind. In this article, we report an experiment with manifoldly entangled photons that demonstrates a

stronger object–property separation, whereby an object can permanently drop a certain property and acquire a property that it did not have from another object11. The photons are taken as

“Cheshire cats”, and their polarisations as “grins”. A bilayer Franson interferometer is exploited to post-select over the desired ensemble. The trails of the cats and grins can be exposed

by weak values for the corresponding observables, from which it is deduced that both of the grins are first separated from their carrier cats and then swapped. The required weak values are

extracted by means of perturbation, more explicitly, adding various kinds of density filters to cast imaginary-time evolution (ITE) on the system, which spares the need of introducing an

additional pointer to a complex system for weak value extraction. This method may also find its usage in other fields such as contextuality-based quantum computation18,19 and quantum

metrology20. The results overcome the main criticism of previous experiments that the separation can also be observed in classical systems, and that the disembodiment is temporary. The

apparent separation of the physical properties from the quantum objects, and the exchanges of these properties lucidly exhibit the genuine quantum feature of the quantum Cheshire cats.

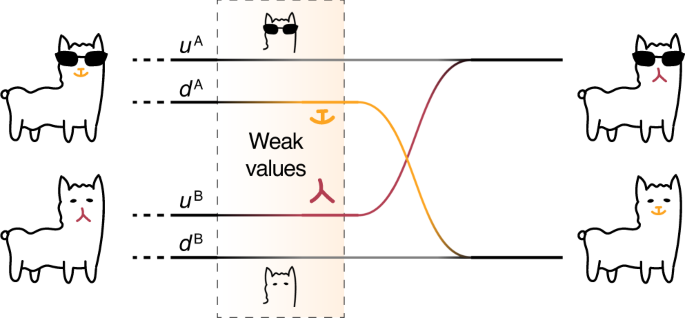

RESULTS SCHEMATIC ILLUSTRATION The narrative of two Cheshire cats exchanging their grins is plotted in Fig. 1. The creatures of Cheshire cats can freely take off their grin in Wonderland,

but are not allowed to do so in the real world. Two Cheshire cats named Anna and Belle are spawned at distant locations. Each of them enters the Wonderland via a one-way channel denoted by

the grey line and sends its grin forward via another one-way channel denoted by the coloured line. The separation can be revealed by a courier called “weak value”. The cats do not expect

that the mischievous designer leads Anna’s coloured grin to appear on Belle and vice versa. Upon returning to reality, Anna gets Belle’s grin and has to put it on to avoid being faceless.

This weird story may actually take place in the quantum realm. A photon, which is a spin-1 boson, is forbidden from being observed without spin. However, it can be separated from its spin

during a quantum process, as is well demonstrated in quantum Cheshire cat experiments14,15,16. By manipulating the channels of photons and their spins to twist the internal link, we can

deterministically swap the spins of two photons while preventing them from appearing at the same site. THEORETICAL LAYOUT A set of properly defined observables can help describe the

perplexing behaviors of quantum Cheshire cats. The path (“cat”) observables, revealing the spatial positions of the cats, read \({\Pi }_{{u}}\equiv \left|{u}\right\rangle \left\langle

{u}\right|\) and \({\Pi }_{{d}}\equiv \left|{d}\right\rangle \left\langle {d}\right|\), with _u_ and _d_ denoting the two possible paths a Cheshire cat can take. Both of the projectors have

an eigenvalue of one to indicate the existence of the cat, and an eigenvalue of zero to indicate the absence of the cat in the corresponding path. The spin observable is given by the Pauli

operator \({\sigma }_{z}=\left|\uparrow \right\rangle \left\langle \uparrow \right|-\left|\downarrow \right\rangle \left\langle \downarrow \right|\), which has a pair of eigenvalues ±1,

with ↑ and ↓ denoting the smile and frown of a Cheshire cat. To detect the exact spin in one path (“grin”, e.g., in the upper path), a product of the two observables should be introduced,

which reads _σ__z_ ⊗ _Π__u_. The product observable has three eigenvalues: ±1 and 0, corresponding to the eigenstates \(\left|\uparrow \right\rangle \left|{u}\right\rangle\),

\(\left|\downarrow \right\rangle \left|{u}\right\rangle\) and the degenerate subspace spanned by \(\left|\uparrow \right\rangle \left|{d}\right\rangle\) and \(\left|\downarrow \right\rangle

\left|{d}\right\rangle\), respectively. The quantum Cheshire cat effect is best witnessed via the weak values of the cat and grin observables. The weak value of an observable _O_ with

respect to pre-selection \(\left|\xi \right\rangle\) and post-selection \(\left\langle \zeta \right|\) is defined as21: $${\left\langle O\right\rangle }_{{w}}=\frac{\left\langle \zeta | O|

\xi \right\rangle }{\left\langle \zeta | \xi \right\rangle },$$ (1) which describes the conditioned average of the observable for a pre-/post-selected ensemble. By associating the locations

of observables to their corresponding weak values, tracing physical object and properties in a specific process has been made possible14,22. Precisely, for an observable with spectrum of 0

and ±1, a null weak value \({\left\langle O\right\rangle }_{{w}}=0\) indicates that the property represented by the observable is not in presence; a unit weak value \({\left\langle

O\right\rangle }_{{w}}=1\), conversely, indicates that the corresponding property is here. The weak values may have anomalous behaviors. For instance, the settings in the first proposed

quantum Cheshire cat Gedankenexperiment5 leads to \({\left\langle {\Pi }_{u}\right\rangle }_{{w}}={\left\langle {\sigma }_{z}\otimes {\Pi }_{d}\right\rangle }_{{w}}=1\) and \({\left\langle

{\Pi }_{d}\right\rangle }_{{w}}={\left\langle {\sigma }_{z}\otimes {\Pi }_{u}\right\rangle }_{{w}}=0\), so a cat and its grin is discovered at different sites, creating an apparent

object–property separation. What happens to the cats in Fig. 1 successfully passing through the pre- and post-selection? For this ensemble, Anna has travelled through the path marked by _d,_

whereas Belle has taken the path _u_; the spin of Anna appears in the path _u_, whereas the spin of Belle appears in the path _d_. It follows the above properties of weak value that:

$${\left\langle {\Pi }_{\mu }^{\nu }\right\rangle }_{{w}}={\delta }_{\mu {d}}{\delta }_{\nu {A}}+{\delta }_{\mu {u}}{\delta }_{\nu {B}},$$ (2) $${\left\langle {\sigma }_{z}^{\nu }\otimes

{\Pi }_{\mu }^{\nu }\right\rangle }_{{w}}={\delta }_{\mu {u}}{\delta }_{\nu {A}}+{\delta }_{\mu {d}}{\delta }_{\nu {B}},$$ (3) here, the _δ_ symbol is the Kronecker-_δ_ function, _μ_ ∈ {_u_,

_d_} denotes possible paths and _ν_ ∈ {_A_, _B_} indexes the cat names. Given the set of weak values, when the two channels marked by _u_ combine, the input modes, namely, the spin from

Anna and the body from Belle, have to join each other to fire a detector. A similar event takes place on the channels marked by _d_, where Anna acquires Belle’s spin. In other words, each of

the two quantum Cheshire cats deterministically swaps grin with its counterparts. One may ask whether the particular configuration described above can even be arranged. Interestingly,

entanglement in quantum theory supplies the required catalyst here, that the two cats can indeed exchange their grins even they can never be found at the same location. To observe such a

counterintuitive phenomenon, the system should be pre-selected as a four-qubit linear cluster state \(\left|\xi \right\rangle =[-\left|{\Phi }^{-}\right\rangle \otimes

\left|{{u}}^{{A}}{{d}}^{{B}}\right\rangle +\left|{\Phi }^{+}\right\rangle \otimes \left|{{d}}^{{A}}{{u}}^{{B}}\right\rangle ]/\sqrt{2}\), and the ensembles for post-selection are accordingly

chosen to be \(\left|\zeta \right\rangle ={\left|D\right\rangle }^{\otimes 2}\otimes \left|{\Psi }^{-}\right\rangle\), with \(\left|D\right\rangle =(\left|\uparrow \right\rangle

+\left|\downarrow \right\rangle )/\sqrt{2}\). Here, the states before and after the direct product symbol correspond to the system’s “cat” and “grin” degrees of freedom. \(\left|{\Phi }^{\pm

}\right\rangle\) and \(\left|{\Psi }^{\pm }\right\rangle\) represent the celebrated Bell states, explicitly defined as \({\left|{\Phi }^{\pm }\right\rangle

}_{{\rm{grin}}}=\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}(\left|{\uparrow }^{{A}}{\uparrow }^{{B}}\right\rangle \pm \left|{\downarrow }^{{A}}{\downarrow }^{{B}}\right\rangle )\), and \({\left|{\Psi }^{\pm

}\right\rangle }_{{\rm{cat}}}=\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}(\left|{{u}}^{{A}}{{\rm{d}}}^{{\rm{B}}}\right\rangle \pm \left|{{d}}^{{A}}{{u}}^{{B}}\right\rangle )\). The superscripts “_A_” and “_B_” are

indices for cats Anna and Belle. The exchange of grins can be verified by substituting \(\left|\xi \right\rangle\) and \(\left\langle \zeta \right|\) into (1) to immediately recover (2) and

(3). Observing that \({\Pi }_{{u}}^{{A}}{\Pi }_{{u}}^{{B}}\left|\xi \right\rangle ={\Pi }_{{d}}^{{A}}{\Pi }_{{d}}^{{B}}\left|\xi \right\rangle =0\), such behavior is strictly forbidden for a

localised classical object because it invokes action at a distance, so the Cheshire cats here are purely from the quantum realm. WEAK VALUE EXTRACTION It is argued that the quantum Cheshire

cat effect is nothing other than an optical illusion. As a strong measurement corresponding to an operator projects the system onto its eigenspace by Lüder’s rule, a series of non-commuting

sequential measurements that do not share all eigenvectors cannot reveal meaningful information about the original state. However, a disturbance-friendly measurement (i.e., weak

measurement), can actually reveal the paradox, which can be witnessed from the weak values of the observables extracted from the pre- and post-selected ensembles5. The quantum measurement

procedure, including von Neumann measurement, positive operator-valued measurement and weak measurements, requires an auxiliary pointer object for readout26,27. See Fig. 2a, to extract the

weak value \({\left\langle {O}_{s}\right\rangle }_{{w}}\), the standard procedure using weak measurement weakly couples the system to a pointer with a Hamiltonian

\(\tilde{{\mathcal{H}}}={O}_{s}\otimes P\), where the subscript _s_ indicates that _O__s_ only acts on the system, and _P_ is the pointer’s momentum operator. One then strongly collapses the

system to some judiciously chosen target states. Because the pointer is now entangled with the system by interaction \(\tilde{{\mathcal{U}}}=\exp (-i\tilde{{\mathcal{H}}}t)\), it will be

steered to different conditional output states, enabling the calculation of corresponding weak value21. Are there alternative approaches to extract the weak value other than weak

measurements? Recent advances have given affirmative answers. For instance, in the work of directly measuring an entangled biphoton state28, the authors read out the required weak values of

non-local observables via strong measurements and the concept of modular value29. Besides, a linear relationship exists between the probability of successful post-selection and the strength

of a unitary perturbation. Consequently, the imaginary part of the weak value can be linked to the linear model’s slope23. In this approach, no ancillary pointer is needed and the

interaction of weak measurement can be effectively substituted by some perturbations in a weak manner where quantum coherence can still be preserved. For an observation of quantum Cheshire

cats, schemes of weak value extraction with the feature of resource-saving are quite preferred, as both the photons’ polarisation and path degrees of freedom have been consumed. Because the

coefficients in the pre- and post-selection rays in the scheme are real, the weak values for both the “cat” and the “grin” observables have no imaginary part. Following the insight of ref.

23, here we establish a linear relationship between the probability of successful post-selection and the strength of perturbations with the form of ITE, and exploit this relationship to

characterise the weak values without introducing any auxiliary pointer states. The non-unitary ITE evolution generated by an observable _O_ reads

\({\mathcal{U}}({\mathcal{H}},t)={e}^{-{\mathcal{H}}t}\), where \({\mathcal{H}}=O\) is the Hamiltonian of the system and the interaction time _t_ → 0 is an analogue to the coupling strength

in the system–pointer coupling process. Explicitly, let \({N}_{0}=| \left\langle \xi | \zeta \right\rangle {| }^{2}\) and \(N({\mathcal{U}})=| \left\langle \zeta | {\mathcal{U}}| \xi

\right\rangle {| }^{2}\) be the probabilities of conducting a successful post-selection before and after applying the perturbation, then, the real part of the weak value can be linked to the

probability correction, that: $${\left.\frac{\partial }{\partial t}\frac{N({\mathcal{U}})}{{N}_{0}}\right|}_{t\to 0}=-2{\rm{Re}}{\left\langle O\right\rangle }_{{w}}.$$ (4) The detailed

proof is presented in the “Methods” section. Consequently, when ITEs with sufficiently small interaction times (see Supplementary Note 2) are imposed on the pre-selection state, a linear

relationship exists between the probability correction and the interaction time, and the model’s slope is proportional to the real part of the weak value of the ITE’s generating Hamiltonian.

EXPERIMENTAL IMPLEMENTATION We will demonstrate the exchange of grins between quantum Cheshire cats with an optical setup. Two entangled photons are adopted as the quantum Cheshire cats.

Utilising the photon’s intrinsic pseudo-spin degree of freedom, namely, the polarisation, the smile (\(\left|\uparrow \right\rangle\)) and frown (\(\left|\downarrow \right\rangle\)) of the

cats are represented by photon’s horizontal (\(\left|H\right\rangle\)) and vertical (\(\left|V\right\rangle\)) polarisation. To prepare the desired ensembles, a hyperentanglement biphoton

source and a bilayer Franson interferometer are exploited. Each photon has two possible paths, one in the upper layer of the Franson interferometer and one in the lower layer. They

correspond to the path states \(\left|u\right\rangle\) and \(\left|d\right\rangle\), respectively. The photon source of the experimental setup is shown in Fig. 2b. A vertically polarised

ultraviolet laser (_λ_ = 406.7 nm) was focused on a type-I cut _β_-barium borate (BBO) crystal. The degenerate spontaneous parametric down-conversion (SPDC) process allows horizontally

polarised photon pair emission at _λ_ = 813.4 nm along two opposite rays on a conical surface. Both the laser and the down-converted photons’ wavefunction pass through a QWP (_λ_/4 at 813.4

nm, optical axis oriented at 45°), reflect off a spherical (_f_ = 150 mm) mirror, pass through the wave plate and are focused again on the BBO crystal. The polarisation of down-converted

photons is rotated to vertical by double-passing the QWP, and the SPDC process can again produce horizontally polarised photon pairs. Finally, a positive lens (_f_ = 150 mm) transforms the

conical parametric emission to cylindrical. Due to the system’s confocal structure and small dispersion, the wavefunctions of down-converted photons from successive pumping processes are

spatially and temporally overlapped, thereby producing an entanglement ring. Selecting two pairs of opposite points on the ring results in biphoton polarisation-path hyperentangled states25.

The photon on the left side is chosen as “Anna” and that on the right side is called “Belle”. The hyperentangled state reads \({\left|{\Phi }^{+}\right\rangle }_{{\rm{pol}}}\otimes

{\left|{\Psi }^{+}\right\rangle }_{{\rm{path}}}\), which is further converted to the cluster state \(\left|\xi \right\rangle\) by inserting a half-wave plate (HWP) with its optical axis

oriented at 0° into Anna side’s upper interferometer arm, as shown in Fig. 2c. The post-selection on \(\left|\zeta \right\rangle\) is conducted by first superimposing Anna and Belle’s

wavefunction on the upper and lower layers, respectively, on a beam splitter (BS), and then picking out the diagonal polarisation with a set of quarter-wave plates (QWPs) and HWPs, followed

by a polarising beam splitter (PBS). The spatial wavefunction is maximally entangled for the Franson interference occurring on the BS (more details are given in the Supplementary Note 5). To

implement the perturbation of ITE and acquire the weak values, a neutral density (ND) filters or polarising dependent (PD, only attenuates vertically polarised components) filter is

inserted into one of the four arms of the interferometer before recombining the photons on the BS, and its position is slightly adjusted to block different portions of light, effectively

changing _t__n_(_p_). The corresponding Hamiltonians are \({\Pi }_{\mu }^{\nu }\) and \({({\mathbb{1}}-{\sigma }_{z})}^{\nu }/2\otimes {\Pi }_{\mu }^{\nu }\), respectively. So, an ND filter

serves to obtain the path weak value \({\langle {\Pi }_{\mu }^{\nu }\rangle }_{{w}}\), and the spin weak value \({\langle {\sigma }_{z}^{\nu }\otimes {\Pi }_{\mu }^{\nu }\rangle }_{{w}}\) is

linked to the system’s behaviors under both kinds of filter insertion. Moreover, let us define the intensity transmissivity _γ__n_, _γ__p_ of the filter as the intensity ratio of an

unpolarised light after and before passing through the neutral and polarising filter, respectively. Then, the interaction time _t__n_(_p_) can be associated by _γ__n_(_p_) by \({\gamma

}_{{n}}={e}^{-2{t}_{{n}}}\) and \({\gamma }_{{p}}=(1+{e}^{-2{t}_{{p}}})/2\). Note that the definition for polarising filter is equivalent with a 2_γ__p_ − 1 and unity transmissivity for

vertically and horizontally polarised photons, respectively. Also, let \({N}_{\mu ,{n}({p})}^{\nu }\) denote the ratio of coincidence rates after and before neutral or polarising filter

insertion in the path _μ_ of photon _ν_. Substituting the definitions of Hamiltonians to (4) yields: $${\left\langle {\Pi }_{\mu }^{\nu }\right\rangle }_{{w}}=-\frac{1}{2}\frac{\partial

{N}_{\mu ,{n}}^{\nu }}{\partial {t}_{{n}}},$$ (5) $${\left\langle {\sigma }_{z}^{\nu }\otimes {\Pi }_{\mu }^{\nu }\right\rangle }_{{w}}=-\frac{1}{2}\frac{\partial {N}_{\mu ,{n}}^{\nu

}}{\partial {t}_{{n}}}+\frac{\partial {N}_{\mu ,{p}}^{\nu }}{\partial {t}_{{p}}}.$$ (6) The detailed proof of (6) goes to the “Methods” section. Finally, the eight weak values \({\langle

{\Pi }_{\mu }^{\nu }\rangle }_{{w}}\) and \({\langle {\sigma }_{z}^{\nu }\otimes {\Pi }_{\mu }^{\nu }\rangle }_{{w}}\) are deduced by filtering the photons in one arm by different ratios,

recording the corresponding counting rates, and least square fitting the linear model (6) with recorded data points of coincidence against transmissivity, whose slope can be related to the

weak values. The brightness of the cluster state is about 1 × 103 counts per second, and integration time for each data point is 100 s. The rate of dark coincidence events is of the

magnitude of 10−2 Hz. The precise implementation of pre- and post-selection (see Supplementary Notes 3 and 5) guarantees the weak values have negligible imaginary parts. For each data point,

the count of coincident events \({N}_{\mu ,{n}({p})}^{\nu }\) is normalised by the value when the filter is not inserted, and the _N_-_t_ data points are asymptotically fitted to a linear

model in the neighbourhood of _t__n_(_p_) → 0, so the required derivatives are given by the model’s slope. The eight groups of recorded \({N}_{\mu ,{n}({p})}^{\nu }\)-_t_ points and their

linear fitted models are plotted in Fig. 3. From the models’ slopes, the weak values are deduced to be \({\left\langle {\Pi }_{{u}}^{{A}}\right\rangle }_{{w}}=-0.01(3)\), \({\left\langle

{\Pi }_{{d}}^{{A}}\right\rangle }_{{w}}=1.04(4)\), \({\left\langle {\Pi }_{{u}}^{{B}}\right\rangle }_{{w}}=1.11(4)\), \({\left\langle {\Pi }_{{d}}^{{B}}\right\rangle }_{{w}}=0.06(4)\),

\({\left\langle {\sigma }_{{u}}^{{A}}\right\rangle }_{{w}}=1.01(3)\), \({\left\langle {\sigma }_{{d}}^{{A}}\right\rangle }_{{w}}=-0.04(4)\), \({\left\langle {\sigma

}_{{u}}^{{B}}\right\rangle }_{{w}}=0.10(2)\), and \({\left\langle {\sigma }_{{d}}^{{B}}\right\rangle }_{{w}}=0.04(3)\). The counting events for photon detection follow Poisson distribution,

and following this statistic, the standard deviation for weak values given in the parentheses is numerically estimated via Monte Carlo simulation. The calculated values are consistent with

the theoretical values, and shows that for the successfully post-selected ensemble, Anna always comes from the lower layer, whereas its spin effectively comes from the upper layer. The case

of Belle is contrary, that the photon is from the upper layer with its spin separated on the lower layer. Finally, on the BS, Anna eventually receives the spin of Belle, and Belle captures

Anna’s spin. DISCUSSION The usefulness and genuine quantum property of quantum Cheshire cat have been intensely debated. Introducing second-order interference may provide some insight into

these topics. Comparing with the original quantum Cheshire cat proposal with only first-order interference, the observed effects in this demonstration are significantly more robust, because

entanglement provides additional resilience against local disturbances. For example, when a local disturbance of the bit flip error is applied on one of the arms of the interferometer, the

phenomenon of quantum Cheshire cat is not affected, that the spins can still not be detected on the interferometer arms where the photons can be detected (proof details are given in

Supplementary Note 4). This result is not valid for first-order demonstrations, where the Cheshire cat is more prone to disturbance17. Moreover, when the bit flip error is applied to the

arms with \({\langle {\sigma }_{z}^{\nu }\otimes {\Pi }_{\mu }^{\nu }\rangle }_{{w}}=0\), the weak values observed in (2) and (3), together with the final counting rate, are left unchanged.

This observation supports the proposal5, that the unwanted disturbance can be completely removed in a post-selected manner by producing quantum Cheshire cats, where the affected observables

are confined out of the regions with disturbance. Hopefully, its application may also be found in the tasks about quantum communication, for example, teleporting a spin through a noisy

channel. Regarding the genuine quantum property of quantum Cheshire cats, although quantum objects are used in previous demonstrations, the observed effects did not exclude the

interpretation with other languages such as classical electrodynamics16. Conversely, the entangled photons, together with the Franson interference exploited in this demonstration, manifest

Bell-type non-locality and reject any classical description. By unveiling the nature of quantum Cheshire cat, the stereotype that a property must faithfully belong to an object is overthrown

and becomes another counterintuitive, seemingly paradoxical phenomenon provided by the quantum theory. We have observed the phenomenon of grin swapping between two quantum Cheshire cats,

which only appears in a pre- and post-selected entangled quantum system. The required weak values are acquired with high accuracy by casting ITE in a linear optics setup. Our experiment

should help foster new research in the area of quantum information and inspire new ideas regarding the ontology of physical properties beyond the dependent object. METHODS PROOF OF THE

PERTURBATION METHOD In this section, we derive the link between the probability of successful post-selection and the interaction time in the context of ITE. The result for a unitary

perturbation was already described in ref. 23. Originating from Wick rotation in special relativity30, the ITE operation is applied in, e.g., quantum field theory31 and quantum

simulations32. The parameter _t_ is not generally restricted, however, in this scheme it has to be sufficiently small to resemble a vanishing interaction time and guarantee minimal

disturbance of the system. Recall that for ITE the relation between non-unitary operation and the Hamiltonian is \({\mathcal{U}}({\mathcal{H}},t)=\exp (-{\mathcal{H}}t)\). Assuming weak

interaction _t_ → 0, the detection probability of a pre- and post-selected event perturbed by ITE (with Maclaurin series up to the first order of _t_) reads:

$$\begin{array}{c}N({\mathcal{U}})=| \left\langle \zeta | {\mathcal{U}}| \xi \right\rangle {| }^{2}=| \left\langle \zeta | (1-Ot+...)| \xi \right\rangle {| }^{2}\\ \quad \, \,

={N}_{0}-2t{\rm{Re}}\left\langle \xi | \zeta \right\rangle \left\langle \zeta | O| \xi \right\rangle +{\mathcal{O}}({t}^{2}),\end{array}$$ (7) where in the last term the

big-\({\mathcal{O}}\) notation is adopted, which is not to be confused with the operator _O_ that generates the ITE. By dividing both sides of Eq. (7) by _N_0 and taking partial derivative

with respect to _t_: $${\left.\frac{\partial }{\partial t}\frac{N({\mathcal{U}})}{{N}_{0}}\right|}_{t\to 0}=-2{\rm{Re}}\left(\frac{\left\langle \zeta | O| \xi \right\rangle }{\left\langle

\zeta | \xi \right\rangle }\right)=-2{\rm{Re}}{\left\langle O\right\rangle }_{{w}}.$$ (8) From Eq. (8), the real part of the weak value \({\left\langle O\right\rangle }_{{w}}\) is half of

the additive inverse of the derivative of the detection probability normalised by its undisturbed value, with respect to the interaction time _t_. In this demonstration, all parameters in

pre- and post-selection states and the ITE non-unitary evolution operator are real numbers, so all weak values have to be purely real. From now on we do not distinguish the weak value from

its real part. For location measurement at path _μ_ of photon _ν_, the Hamiltonian is taken to be \({{\mathcal{H}}}_{\mu ,{n}}^{\nu }={\Pi }_{\mu }^{\nu }\), the corresponding ITE operator

acting on the state vector is \({{\mathcal{U}}}_{\mu ,{n}}^{\nu }({{\mathcal{H}}}_{\mu ,{n}}^{\nu },{t}_{{n}})={\mathbb{1}}-{\Pi }_{\mu }^{\nu }(1-{e}^{-{t}_{{n}}})\). The operation

complying with this ITE is to decrease the photon number in photon _ν_’s path _μ_. Explicitly, an ND filter with transmissivity \({\gamma }_{{n}}={e}^{-2{t}_{{n}}}\) is introduced to

partially block this path, which multiplies the coincidence rates by \({N}_{\mu ,{n}}^{\nu }\). It follows from (8) that (omitting _t_ → 0): $${\left\langle {\Pi }_{\mu }^{\nu }\right\rangle

}_{{w}}=-\frac{1}{2}\frac{\partial {N}_{\mu ,{n}}^{\nu }}{\partial {t}_{{n}}}.$$ (9) Similarly, for spin measurement at path _μ_ of photon _ν_ the Hamiltonian is chosen to be

\({{\mathcal{H}}}_{\mu ,{p}}^{\nu }={({\mathbb{1}}-{\sigma }_{z})}^{\nu }\otimes {\Pi }_{\mu }^{\nu }/2\). Then, \({{\mathcal{U}}}_{\mu ,{p}}^{\nu }({{\mathcal{H}}}_{\mu ,{p}}^{\nu

},t)={\mathbb{1}}-{\Pi }_{\mu }^{\nu }{({\mathbb{1}}-{\sigma }_{z})}^{\nu }(1-{e}^{-{t}_{{p}}})/2\), experimentally, this corresponds to a PD filter insertion, multiplying the coincidence

rates by \({N}_{\mu ,{p}}^{\nu }\). By substituting the form of ITE operator into (8) and taking advantage of (9): $${\left\langle {\Pi }_{{d}}^{\nu }\right\rangle }_{{w}}-{\left\langle

{\sigma }_{z}^{\nu }\otimes {\Pi }_{\mu }^{\nu }\right\rangle }_{{w}}=-\frac{\partial {N}_{\mu ,{p}}^{\nu }}{\partial {t}_{{p}}},$$ (10) $${\left\langle {\sigma }_{z}^{\nu }\otimes {\Pi

}_{\mu }^{\nu }\right\rangle }_{{w}}=-\frac{1}{2}\frac{\partial {N}_{\mu ,{n}}^{\nu }}{\partial {t}_{{n}}}+\frac{\partial {N}_{\mu ,{p}}^{\nu }}{\partial {t}_{{p}}}.$$ (11) Observing that

the transmissivity for vertically and horizontally polarised photons are \({e}^{-2{t}_{{p}}}\) and 1 respectively, \({\gamma }_{{p}}=(1+{e}^{-2{t}_{{p}}})/2\) again correlates the

interaction time with the experimentally measurable transmissivity. POLARISING DENSITY FILTER For the measurement of photon spin information, the required PD filter is a synthetic element.

The formation of the PD filter is shown in Fig. 2d. A pair of BDs, together with two HWPs separate and reconverges the horizontally and vertically polarised wavefunction. An ND filter on the

vertically polarised path filters a fraction of photons to mimic the change of _t__p_. DATA AVAILABILITY The data that support the findings of this study are available from the authors upon

request. REFERENCES * Aharonov, Y. & Rohrlich, D. Quantum paradoxes: quantum theory for the perplexed, Physics textbook, (Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2005) p. 289. * Bell, J. On the einstein

podolsky rosen paradox. _Physics_ 1, 195–200 (1964). Article MathSciNet Google Scholar * Kochen, S. & Specker, E. P. The problem of hidden variables in quantum mechanics. _J. Math.

Mech._ 17, 59–87 (1968). MathSciNet MATH Google Scholar * Leggett, A. J. & Garg, A. Quantum mechanics versus macroscopic realism: is the flux there when nobody looks?. _Phys. Rev.

Lett._ 54, 857–860 (1985). Article ADS MathSciNet CAS Google Scholar * Aharonov, Y., Popescu, S., Rohrlich, D. & Skrzypczyk, P. Quantum cheshire cats. _New J. Phys._ 15, 113015

(2013). Article ADS Google Scholar * Carroll, L. Alice’s adventures in wonderland (Broadview Press, 1865). * Bancal, J.-D. Isolate the subject. _Nat. Phys._ 10, 11–12 (2013). Article

Google Scholar * Ibnouhsein, I. & Grinbaum, A. Twin quantum cheshire photons, arXiv:1202.4894 [quant-ph] (2012). * Guryanova, Y., Brunner, N. & Popescu, S., The complete quantum

cheshire cat, arXiv:1203.4215 [quant-ph] (2012). * Lorenzo, A. D. Hunting for the quantum cheshire cat, arXiv:1205.3755 [quant-ph] (2012). * Das, D. & Pati, A. K. Can two quantum chesire

cats exchange grins? _New J. Phys._ arXiv:1904.07707 [quant-ph] (2020). * Das, D. & Pati, A. K. Teleporting grin of a quantum chesire cat without cat, arXiv:1903.04152 [quant-ph]

(2019). * Albert, D. Z., Aharonov, Y. & D’Amato, S. Curious new statistical prediction of quantum mechanics. _Phys. Rev. Lett._ 54, 5–7 (1985). Article ADS MathSciNet CAS Google

Scholar * Denkmayr, T., Geppert, H., Sponar, S., Lemmel, H. & Matzkin, A. Observation of a quantum cheshire cat in a matter-wave interferometer experiment. _Nat. Commun._ 5, 4492

(2014). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Ashby, J. M., Schwarz, P. D. & Schlosshauer, M. Observation of the quantum paradox of separation of a single photon from one of its

properties. _Phys. Rev. A_ 94, 012102 (2016). Article ADS Google Scholar * Atherton, D. P., Ranjit, G., Geraci, A. A. & Weinstein, J. D. Observation of a classical cheshire cat in an

optical interferometer. _Opt. Lett._ 40, 879–881 (2015). Article ADS Google Scholar * Corrêa, R., Santos, M. F., Monken, C. H. & Saldanha, P. L. quantum cheshire cat’ as simple

quantum interference. _New J. Phys._ 17, 053042 (2015). Article ADS MathSciNet Google Scholar * Pusey, M. F. Anomalous weak values are proofs of contextuality. _Phys. Rev. Lett._ 113,

200401 (2014). Article ADS Google Scholar * Howard, M., Wallman, J., Veitch, V. & Emerson, J. Contextuality supplies the ‘magic’ for quantum computation. _Nature_ 510, 351–355 (2014).

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Pati, A. K., Mukhopadhyay, C., Chakraborty, S., & Ghosh, S. Quantum precision thermometry with weak measurement, arXiv:1901.07415 [quant-ph] (2019).

* Aharonov, Y., Albert, D. Z. & Vaidman, L. How the result of a measurement of a component of the spin of a spin-1/2 particle can turn out to be 100. _Phys. Rev. Lett._ 60, 1351–1354

(1988). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Danan, A., Farfurnik, D., Bar-Ad, S. & Vaidman, L. Asking photons where they have been. _Phys. Rev. Lett._ 111, 240402 (2013). Article ADS

CAS Google Scholar * Dressel, J., Malik, M., Miatto, F. M., Jordan, A. N. & Boyd, R. W. Colloquium: understanding quantum weak values: basics and applications. _Rev. Mod. Phys._ 86,

307–316 (2014). Article ADS Google Scholar * Kwiat, P. G. Hyper-entangled states. _J. Mod. Opt._ 44, 2173–2184 (1997). Article ADS MathSciNet Google Scholar * Barbieri, M., Cinelli,

C., Mataloni, P. & De Martini, F. Polarization-momentum hyperentangled states: realization and characterization. _Phys. Rev. A_ 72, 052110 (2005). Article ADS Google Scholar * Li,

C.-F., Xu, X.-Y., Tang, J.-S., Xu, J.-S. & Guo, G.-C. Ultrasensitive phase estimation with white light. _Phys. Rev. A_ 83, 044102 (2011). Article ADS Google Scholar * Xu, X.-Y.,

Kedem, Y., Sun, K., Vaidman, L., Li, C.-F. & Guo, G.-C. Phase estimation with weak measurement using a white light source. _Phys. Rev. Lett._ 111, 033604 (2013). Article ADS Google

Scholar * Pan, W.-W., Xu, X.-Y., Kedem, Y., Wang, Q.-Q. & Chen, Z. Direct measurement of a nonlocal entangled quantum state. _Phys. Rev. Lett._ 123, 150402 (2019). Article ADS CAS

Google Scholar * Kedem, Y. & Vaidman, L. Modular values and weak values of quantum observables. _Phys. Rev. Lett._ 105, 230401 (2010). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Wick, G. C.

Properties of bethe-salpeter wave functions. _Phys. Rev._ 96, 1124–1134 (1954). Article ADS MathSciNet CAS Google Scholar * Landsman, N. & van Weert, C. Real- and imaginary-time

field theory at finite temperature and density. _Phys. Rep._ 145, 141–249 (1987). Article ADS MathSciNet Google Scholar * Xu, J.-S., Sun, K., Han, Y.-J., Li, C.-F., Pachos, J. K. &

Guo, G.-C. Simulating the exchange of majorana zero modes with a photonic system. _Nat. Commun._ 7, 13194 (2016). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The

authors acknowledge insightful comments from Paul Skrzypczyk. This work was supported by National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grants Nos. 2017YFA0304100, 2016YFA0302700),

the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants Nos. 11874343, 61805228, 11774335, 11821404, 61725504 and U19A2075), Key Research Program of Frontier Sciences, CAS (Grant No.

QYZDY-SSW-SLH003), Science Foundation of the CAS (Grant No. ZDRW-XH-2019-1), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Grant Nos. WK2470000026, WK2030380017, WK2030000017,

WK2470000030), the CAS Youth Innovation Promotion Association (No. 2020447), Anhui Initiative in Quantum Information Technologies (Grants Nos. AHY020100 and AHY060300). J.L.C. was supported

by the National Natural Science Foundations of China (Grant No. 11875167) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, Nankai University (Grant No. 63191507). AUTHOR

INFORMATION Author notes * These authors contributed equally: Zheng-Hao Liu, Wei-Wei Pan. AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * CAS Key Laboratory of Quantum Information, University of Science and

Technology of China, Hefei, 230026, China Zheng-Hao Liu, Wei-Wei Pan, Xiao-Ye Xu, Mu Yang, Ze-Yu Luo, Kai Sun, Jin-Shi Xu, Chuan-Feng Li & Guang-Can Guo * CAS Centre For Excellence in

Quantum Information and Quantum Physics, University of Science and Technology of China, Hefei, 230026, China Zheng-Hao Liu, Wei-Wei Pan, Xiao-Ye Xu, Mu Yang, Ze-Yu Luo, Kai Sun, Jin-Shi Xu,

Chuan-Feng Li & Guang-Can Guo * Theoretical Physics Division, Chern Institute of Mathematics, Nankai University, Tianjin, 300071, China Jie Zhou & Jing-Ling Chen Authors * Zheng-Hao

Liu View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Wei-Wei Pan View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar *

Xiao-Ye Xu View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Mu Yang View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar

* Jie Zhou View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Ze-Yu Luo View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google

Scholar * Kai Sun View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Jing-Ling Chen View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed

Google Scholar * Jin-Shi Xu View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Chuan-Feng Li View author publications You can also search for this author

inPubMed Google Scholar * Guang-Can Guo View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CONTRIBUTIONS X.-Y.X. and J.-S.X. constructed the theoretical

scheme. Z.-H.L., W.-W.P. and M.Y. designed the experiment. W.-W.P. and Z.-H.L. performed the experiment. J.Z., K.S. and J.-L.C. contributed to the theoretical analysis. X.-Y.X., Z.-H.L. and

Z.-Y.L. wrote the paper. J.-S.X. and X.-Y.X. supervised the theoretical part of the project. C.-F.L. and G.-C.G. supervised the project. All authors read the paper and discussed the results.

CORRESPONDING AUTHORS Correspondence to Xiao-Ye Xu, Jing-Ling Chen, Jin-Shi Xu or Chuan-Feng Li. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS The authors declare no competing interests.

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION PEER REVIEW INFORMATION _Nature Communications_ thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. PUBLISHER’S NOTE Springer

Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS OPEN

ACCESS This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format,

as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third

party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the

article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright

holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Liu, ZH., Pan, WW., Xu, XY. _et al._

Experimental exchange of grins between quantum Cheshire cats. _Nat Commun_ 11, 3006 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-16761-0 Download citation * Received: 05 December 2019 *

Accepted: 21 May 2020 * Published: 15 June 2020 * DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-16761-0 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this

content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative