Play all audios:

ABSTRACT The challenge of monitoring _in planta_ dynamic changes of NADP(H) and NAD(H) redox states at the subcellular level is considered a major obstacle in plant bioenergetics studies.

Here, we introduced two circularly permuted yellow fluorescent protein sensors, iNAP and SoNar, into _Arabidopsis thaliana_ to monitor the dynamic changes in NADPH and the NADH/NAD+ ratio.

In the light, photosynthesis and photorespiration are linked to the redox states of NAD(P)H and NAD(P) pools in several subcellular compartments connected by the malate-OAA shuttles. We show

that the photosynthetic increases in stromal NADPH and NADH/NAD+ ratio, but not ATP, disappear when glycine decarboxylation is inhibited. These observations highlight the complex interplay

between chloroplasts and mitochondria during photosynthesis and support the suggestions that, under normal conditions, photorespiration supplies a large amount of NADH to mitochondria,

exceeding its NADH-dissipating capacity, and the surplus NADH is exported from the mitochondria to the cytosol through the malate-OAA shuttle. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS A FAMILY

OF NADPH/NADP+ BIOSENSORS REVEALS IN VIVO DYNAMICS OF CENTRAL REDOX METABOLISM ACROSS EUKARYOTES Article Open access 19 December 2024 THE MOLECULAR PH-RESPONSE MECHANISM OF THE PLANT

LIGHT-STRESS SENSOR PSBS Article Open access 16 April 2021 PROBING PLANT SIGNAL PROCESSING OPTOGENETICALLY BY TWO CHANNELRHODOPSINS Article Open access 28 August 2024 INTRODUCTION Adenosine

triphosphate (ATP), nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH), and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH) are crucial energy molecules in living systems. Numerous studies have

measured these metabolites in vitro, using bioluminescence, HPLC, mass spectrometry, enzymatic, and radioactive methods. However, in vitro methods require the extraction of ATP, NADPH, and

NADH from tissues before measurements can be carried out1 and therefore cannot determine the instant levels of these metabolites in different subcellular compartments of different cells in a

tissue. Recently, our group has employed a novel MgATP2−-specific Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET)-based sensor to study the in vivo ATP levels of the plastids and cytosol of

different tissues in _Arabidopsis thaliana_ (Arabidopsis)2. A change in the FRET signal reflects a change in MgATP2− concentration. By using this ATP sensor and a pH sensor, we have shown

that the stromal ATP concentration is significantly lower than the cytosolic ATP concentration; that the import of ATP into mature chloroplasts is impeded by the downregulation of nucleotide

transporters; that cytosolic ATP does not enter mature chloroplasts and is, therefore, unlikely to support the Calvin–Benson–Bassham (CBB) cycle; that, instead of ATP import, in Arabidopsis

it is the export of reducing equivalents from chloroplasts that balances the NADPH/ATP supply from the linear electron flow and the NADPH/ATP demand of the CBB cycle2. Here, we employed two

circularly permuted yellow fluorescent protein-based protein sensors, iNAP3 and SoNar4, to measure the _in planta_ dynamic changes of NADPH and the NADH/NAD+ ratio induced by illumination

in several subcellular compartments of Arabidopsis plants. These sensors were engineered from the bacterial Rex repressor capable of sensing pyridine dinucleotides redox states, and have

many desirable properties such as intense fluorescence, rapid response, high specificity, and large dynamic range. Similar to the FRET based ATP sensor, the measurements of these sensors are

also ratiometric and are less prone to the varied sensor expression levels in different tissues and compartments. We used stably transformed lines expressing these sensors to investigate

photosynthesis and photorespiration. Ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (Rubisco) carries out the initial step in the fixation of CO2 during photosynthesis. Rubisco is a slow

enzyme, with a _k_cat of 1–10 s−1 5. Although it has a selectivity for CO2 over O2 of almost a factor of 100, due to the much higher concentration of O2 (21%) than CO2 (0.4%) in the

atmosphere, it is estimated that for every three CO2 molecules fixed in C3 plants, about one O2 molecule is mistakenly utilized by Rubisco to generate one 3-phosphoglycerate (3-PG) and one

2-phosphoglycolate (2-PG) molecule6,7. The recycling of the photorespiration product 2-PG back to 3-PG involves eight enzymatic steps in chloroplasts, mitochondria, and peroxisomes. Hence,

photorespiration has been regarded as a wasteful process due to the additional consumption of stromal ATP and liberation of CO2 in mitochondria in the cycle8. During photorespiration, one

NADH, one CO2, and one NH3 molecule are generated in the mitochondria through the conversion of two glycine molecules to one serine cooperatively by glycine decarboxylase (GDC) and serine

hydroxymethyl transferase (SHMT). A certain amount of serine is exported to the cytosol for other uses9, whereas most is imported into peroxisomes and converted into hydroxypyruvate, which

is then reduced to glycerate by hydroxypyruvate reductase (HPR), at the expense of NADH molecules. By converting the malate imported into the organelle, peroxisomal NAD-dependent malate

dehydrogenase (NAD-MDH) provides the NADH required for hydroxypyruvate reduction10. During photosynthesis, the linear electron flow (LEF) generates ATP and NADPH at a ratio of 1.2811,

whereas the CBB cycle requires ATP and NADPH at a 1.5 ratio, resulting in a deficiency of ATP12 or an excess of NADPH13. Although the cyclic electron flow can contribute extra ATP, mature

mesophyll chloroplasts are unable to import cytosolic ATP2. Hence, chloroplasts must recycle excess NADPH into NADP+ to serve as the electron acceptor during photosynthesis to balance the

ratio of stromal ATP to NADPH. In chloroplasts, NADP+ is recycled from NADPH via three major routes: the CBB pathway and 3-phosphoglyceric acid/triose phosphate (PGA/TP) exchange coupled

with it, fatty acid synthesis, and the malate-oxaloacetate (malate-OAA) shuttle. Excess NADPH generated from the LEF can be exported to the cytosol through the shuttle in the form of malate

via the action of NADP-dependent malate dehydrogenase (NADP-MDH)14,15, which converts OAA into malate and regenerates NADP+16. Hence, during daytime, malate builds up in leaf cells, where

most of it is stored in the vacuole, whereas the cytosolic malate concentration is maintained at a relatively constant, low level17. Some cytosolic malate is imported into the peroxisomes,

where it is used by peroxisomal NAD-MDH to recycle OAA and regenerate the NADH required for hydropyruvate reduction10. In mitochondria, both the malate-OAA shuttle12,16,18,19,20,21,22 and

photorespiration23,24 have been proposed to provide reducing equivalents to the mitochondrial electron transport chain (mETC) for ATP production. In a flux balance model of the mature leaves

of C3 plants, both photorespiration and the malate-OAA shuttle are predicted to contribute to feeding NADH into the mETC25. Experimental data obtained from barley leaf protoplasts23,24,26

and isolated mitochondria27 suggest that photorespiration is the major source of reducing equivalents to the mETC. However, this has not been examined in a whole plant level, and the

direction of the flow of reducing equivalents between different subcellular compartments during photosynthesis has not yet been fully resolved28. Here, by employing a NADPH and a NADH/NAD+

sensors, we examined _in planta_ dynamic changes in the NADPH pools and NADH/NAD+ ratio in the stroma and cytosol upon illumination. We suggest that, at the light intensities we used,

photorespiration supplies a large amount of reducing equivalents to mitochondria during photosynthesis, which exceeds the NADH-dissipating capacity of the mETC. Consequently, the surplus

NADH must be exported from the mitochondria to the cytosol through the mitochondrial malate-OAA shuttle. RESULTS ESTABLISHING INAP AND SONAR SENSORS IN ARABIDOPSIS We generated multiple

transgenic Arabidopsis lines in the wild-type (WT, Col-0) background expressing a high-affinity NADPH sensor (iNAP1), a low-affinity NADPH sensor (iNAP4), and an NADH/NAD+ sensor (SoNar) in

the cytosol (Supplementary Fig. 1). These cytosolic sensors were occasionally seen in the nucleus in some tissues (e.g. guard cells). We also fused the iNAP1, iNAP4, and SoNar sensors with

organelle-specific targeting peptides to direct their expression specifically to the plastid stroma and peroxisome. In addition, we generated Arabidopsis lines expressing iNAPc

(Supplementary Fig. 1f–h), in which the ligand binding to pyridine nucleotides is fully abolished in each of these compartments, to serve as a pH control3. At least two independent lines

expressing each sensor in each compartment were selected for analysis. No abnormal phenotype was observed for these lines, and the plant size did not show significant differences among lines

(Supplementary Fig. 1i, j). We imaged the seedlings using a confocal microscope configured to detect chlorophyll autofluorescence (excitation at 488 nm and emission at 629–700 nm). The

presence of iNAP and SoNar fluorescence in the peripheral cytoplasm indicated that these sensors were expressed in the cytosol (Supplementary Fig. 2a), whereas the fluorescence signals of

TKTP-iNAP and TKTP-SoNar (fusions of the plastid-specific chloroplast transketolase transit peptide, TKTP, from _Nicotiana tabacum_) co-localized with chlorophyll autofluorescence,

corroborating the chloroplast expression of both sensors (Supplementary Fig. 2b). We also compared the distribution of iNAP4-SRL and iNAPc-SRL (fusions of iNAP4 and iNAPc with the peroxisome

marker peroxisomal targeting signal type 1, SRL) with that of mRFP-SRL (a fusion of red fluorescent protein with SRL) using transient protoplast transformation. Both iNAP4-SRL and iNAPc-SRL

co-localized with mRFP-SRL in a typical peroxisome pattern visualized in spherical spots, suggesting that both sensors were targeted specifically to peroxisomes (Supplementary Fig. 2c).

However, no Arabidopsis lines expressing SoNar-SRL were obtained after repeated transformation attempts. We also failed to introduce these sensors into mitochondria of WT and _suppressor of

gene silencing 3-13_ (_sgs3-13_)29 lines using the presequence that successfully targeted GFP and the pH sensor cpYFP to mitochondrial matrix (Supplementary Fig. 2d)30,31. NADPH LEVELS ARE

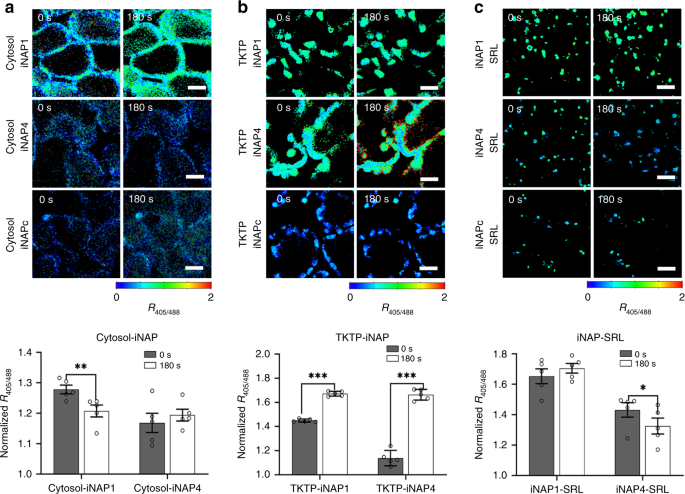

LOWER IN CYTOSOL THAN IN PLASTID STROMA AND PEROXISOME To identify the iNAP sensors with the most suitable affinity for each compartment, we introduced iNAP sensors with high (iNAP1) and low

(iNAP4) NADPH affinities into the cytosol, plastid stroma, and peroxisome. Since the iNAP1 and iNAP4 sensors are highly specific to NADPH3, and NADPH is produced during photosynthesis, the

response of these sensors can be studied by illuminating the plants. Illumination at 296 µmol m−2 s−1 did not significantly affect the cytosolic iNAP4 ratio (Fig. 1a), but it decreased the

cytosolic iNAP1 ratio significantly (_P_ < 0.01), suggesting that the cytosolic NADPH pool was diminished upon exposure to light. Illumination caused significant (_P_ < 0.001)

ratiometric shifts for both the TKTP-iNAP4 and TKTP-iNAP1 sensors (Fig. 1b). However, TKTP-iNAP4 exhibited a greater ratio increment, suggesting that the iNAP1 signal was saturated upon

illumination; we therefore used TKTP-iNAP4 throughout the remainder of our study. In peroxisomes, illumination caused a significant decrease (_P_ < 0.05) in the ratio of the low-affinity

iNAP4-SRL sensor lines but not the high-affinity iNAP1-SRL lines (Fig. 1c), indicating that the NADPH concentration in peroxisomes exceeded the maximum dynamic limit of the iNAP1 sensor.

Similar responses were not observed in illuminated roots, suggesting that the responses observed in the mesophyll were due to photosynthesis (Fig. 2). Together, the differences in saturation

response between iNAP1 and iNAP4 in these compartments suggest that the NADPH level in the cytosol is lower than those in plastid stroma and peroxisome in Arabidopsis. For further _in

planta_ analyses, we employed cytosolic iNAP1, TKTP-iNAP4, and iNAP4-SRL Arabidopsis lines. To test the in vitro and semi in vivo characteristics of the sensor proteins, we adopted

recombinant proteins and seedling root tips to monitor the specificity of NADPH and NADH/NAD+ binding affinity curves. The in vitro _K_d values determined for iNAP1 and iNAP4 at 22 °C were

0.3 μM and 30 μM, respectively, which were much lower than the values 2.0 μM and 120 μM obtained at 37 °C3. The _K_NADH/NAD+ of SoNar at 22 °C was determined to be 0.04 (Supplementary Fig.

3), which was slightly higher than the value (0.025) obtained at 37 °C32. In semi in vivo conditions, the sensors displayed increasing ratios at a higher level or ratio of exogenous

nucleotides (Supplementary Fig. 4), where the _K_d values for iNAP1, iNAP4, and _K_NADH/NAD+ for SoNar were calculated as 2.5, 5.6, and 1.48 μM, respectively, which were different from the

values obtained in vitro. However, the values determined by the semi in vivo protocol might be affected by possible artifacts. First, there are endogenous NADPH in the root cells and zero

value could not be set. As a result, the _K_d value for iNAP1 would be overestimated. Second, the ratios of many cells in the root tips were averaged for ratio calculation but the degree of

penetration of exogenous NADPH into different cells varied. This could lead to an underestimation of the _K_d value for iNAP4. Nonetheless, the semi in vivo experiments showed that the

sensors did response in vivo. RATIOMETRIC IMAGING OF SUBCELLULAR NADPH LEVEL AND NADH/NAD+ RATIO Prior to analyses, we validated two independent lines expressing each sensor. We tested

different confocal laser powers to ensure that the laser power at 405 nm was sufficient and the illumination was not depleted by chlorophyll absorption. Raw _R_405/488 ratios obtained from

3-day-old seedlings of two independent iNAP and SoNar (cytosol, TKTP, and SRL) lines with different confocal laser powers indicated that, within the same tissues, the ratios were practically

identical in all of the independent lines, with no statistically significant differences (Supplementary Fig. 5). These lines stably expressed sensors with different fluorescence intensities

and thus different sensor concentrations in the same compartment, but different lines emitted similar ratios under untreated conditions. We selected the sensor lines with higher

fluorescence intensities to use in our subsequent _in planta_ studies (Line 1 for TKTP-iNAP4, cytosolic SoNar, and TKTP-SoNar and Line 2 for cytosolic iNAP1 and iNAP4-SRL, respectively).

Ratiometric analysis allows measurement of sensors independently of their expression levels, provided that there is a sufficient signal-to-noise ratio and little interference from any

potential autofluorescence. The autofluorescence channel at the UV light spectra (405 nm excitation and 450 ± 17 nm emission) was also set to exclude any potential interference from plant

lignin autofluorescence throughout the experiment. To assess the validity of the collected emission spectra for seedlings expressing iNAP and SoNar, we scanned the emission range for iNAP

and SoNar from 424 to 599 nm in 10-day-old seedlings with 405 nm and 488 nm excitation, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 6). As all iNAP and SoNar sensors showed a characteristic emission

peak at 520 ± 20 nm, which was not seen in the WT, the fluorescence emission at 520 ± 20 nm was significantly lower in the WT control without sensors. Due to the capacity of chloroplasts to

absorb blue wavelength light, we tested different laser powers to avoid possible interference from chloroplasts (Supplementary Fig. 5). Chlorophyll absorption indeed interferes with the

ratio measurement, and therefore the ratios in chlorophyll-containing tissues (e.g., shoots) cannot be compared with those in tissues with less or no chlorophyll (e.g., root). Nonetheless,

the dynamic changes in the sensor ratios in the same compartment under various treatments (e.g., light or inhibitors) can be followed. Moreover, the circularly permuted yellow fluorescent

protein-based iNAP sensors are pH sensitive when it is excited at 488 nm but not at 405 nm3,4, and it is almost certain that plants have numerous cation exchangers that are localized in

different membranes and that may regulate pH changes across the organelles in response to stimuli. Thus, pH effects need to be carefully normalized, which can be done using the pH control

sensor (iNAPc) in parallel experiments. We therefore included an iNAPc control for each subcellular compartment in all measurements to normalize the effects derived from pH interference and

chlorophyll absorption (Supplementary Fig. 7). To determine the redox ratios potentially that could be achievable by the sensors, we exogenously applied the oxidizing agents menadione and

hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and the reducing agent dithiothreitol (DTT) by 5-min infiltration (Supplementary Fig. 8). Menadione and H2O2 are broadly used to oxidize plant cells, and both

mediate ROS formation through the catalytic transfer of electrons from endogenous donors to molecular oxygen. To assess whether these agents might affect the sensors directly, we first

carried out an in vitro experiment. Although H2O2 and menadione had no effect on the sensor ratios (Supplementary Fig. 8), DTT directly suppressed the ratios. Hence, only the _in planta_

results for the oxidizing agents were shown. Menadione and H2O2 significantly reduced the ratios of both iNAP sensors in all three compartments, indicating that the NADPH levels in these

three compartments in the absence of oxidizing treatment were higher than the lowest detection ranges of the iNAP sensors. Menadione and H2O2 treatments significantly lowered the SoNar ratio

in plastid stroma but not in the cytosol (Supplementary Fig. 8), implying that the NADH/NAD+ ratio is very low in the cytosol in darkness. In fact, a highly oxidized NAD(H) pool was

determined in the cytosol of pea protoplasts33 and the NADH/NAD+ ratio was lower in the cytosol than the chloroplasts of barley protoplasts34. The ratios stimulated by illumination at 296

µmol m−2 s−1 were used as controls (Supplementary Fig. 8). We also showed that l-ascorbic acid and reduced glutathione, which are abundant antioxidants in plant cells35, did not affect the

ratios of the sensors in in vitro binding studies (Supplementary Fig. 9). DYNAMIC CHANGES OF NADPH AND NADH/NAD+ UNDER ILLUMINATION To examine the effect of light intensities, we compared

the dynamic changes in subcellular pyridine nucleotides at two light intensities, 40 µmol m−2 s−1 and 296 µmol m−2 s−1. We observed significant increases in stromal NADPH and NADH/NAD+ and

cytosolic NADH/NAD+, and decreases in cytosolic NADPH and peroxisomal NADPH, upon illumination at 296 µmol m−2 s−1 (Fig. 2). However, at 40 µmol m−2 s−1, the NADPH ratiometric shift occurred

only in stroma but not in the cytosol or peroxisome. In addition, both the stromal NADH/NAD+ (Fig. 2e) and the cytosolic NADH/NAD+ were more oxidized (Fig. 2d) at the lower light intensity

than at the higher light intensity, indicating that the redox status of the NADH/NAD+ pool in the cytosol is connected to that in the stroma. The stromal NADPH levels increased only after

60–90 s of illumination, reached a plateau after 120 s, and dropping quickly (within 30 s) after the light was withdrawn. Unlike the NADH/NAD+ ratio in plastid stroma, which dropped below

its basal level within 90 s after light withdrawal (Fig. 2e), the stromal NADPH level did not drop to the basal level, even after 4 min of darkness (Fig. 2b). These data imply that the CBB

cycle is the major consumer of stromal NADPH, as Rubisco carboxylation stops at ~30 s after light withdrawal when the RuBP pool is exhausted36. Since NADP-MDH is active only under

light14,24, whereas NAD-MDH is active in both light and dark conditions37, the malate-OAA shuttle in the chloroplasts can export only stromal NADH reducing equivalents but not stromal NADPH

reducing equivalents in darkness (Fig. 2b, e). As the cytosolic NADH/NAD+ pool was more oxidized than the stromal pool (Fig. 2d), a continuous export of NADH reducing equivalents, resulting

in a stromal NADH/NAD+ ratio even lower than that before illumination, was observed (Fig. 2e). All of the above changes were abolished by the application of the photosynthesis inhibitor DCMU

(Fig. 2), due to its complete inhibition of the LEF (Supplementary Fig. 10b). PHOTORESPIRATION IS THE MAIN NADH CONTRIBUTOR IN MITOCHONDRIA Since Arabidopsis GDC mutant is lethal38, we used

aminoacetonitrile (AAN), an inhibitor of the mitochondrial conversion of glycine to serine and the production of NADH39, to investigate the contribution of photorespiration in supplying

reducing equivalents. AAN does not affect photosynthesis in protoplasts under non-photorespiratory conditions (high CO2), thus supporting its specificity26. In the untreated control,

illumination at 296 µmol m−2 s−1 caused a drastic increase in stromal NADPH (Figs. 1b and 2b) and NADH/NAD+ ratios (Fig. 2e) but a small decrease in both cytosolic (Figs. 1a and 2a) and

peroxisomal NADPH (Figs. 1c and 2c). The cytosolic NADH/NAD+ ratio was increased by illumination at 296 µmol m−2 s−1, but was decreased when the light intensity was only at 40 µmol m−2 s−1

(Fig. 2d). When AAN was applied, however, even illumination at 296 µmol m−2 s−1 failed to increase the stromal NADPH pool (Fig. 3a), and the NADH/NAD+ ratio (Fig. 3b). By contrast, the

production of stromal ATP (Fig. 3c), the electron transport rate (ETR) (Fig. 4k) and the respiration and photosynthesis rates (Supplementary Fig. 10) could still be detected. A pH increment

in mitochondrial matrix was still detected in AAN-treated mitochondria (Fig. 3d), indicating that AAN does not interfere with the mETC machinery and gradient formation during electron

transport. In addition to inhibitor studies, we further simulated a non-photorespiratory condition by including 10 mM NaHCO3 in the half-strength Murashige and Skoog medium during confocal

analysis. Similar to the results of AAN treatment, when NaHCO3 was applied, illumination at 296 µmol m−2 s−1 failed to increase the stromal NADPH pool (Fig. 3h), and the NADH/NAD+ ratio

(Fig. 3i). These results showed that stromal NADPH did not build up when the mitochondria failed to generate NADH by photorespiration. Under normal conditions, illumination at 296 µmol m−2

s−1 caused an increase in the cytosolic NADH/NAD+ ratio (Fig. 2d) and a decrease in the cytosolic NADPH level (Fig. 2a); however, when photorespiration was prevented by AAN, illumination at

296 µmol m−2 s−1 transiently increased the cytosolic NADH/NAD+ (Fig. 3e), but the decrease in the cytosolic NADPH level became smaller (Fig. 3f). Yet, this effect did not occur at 40 µmol

m−2 s−1 (Fig. 3e, f). Although we were unable to target the SoNar sensor to peroxisomes, we showed that illumination at 296 µmol m−2 s−1 caused a decrease in NADPH level in peroxisomes

(Figs. 1c and 2c). This decrease did not occur under 40 µmol m−2 s−1 illumination, probably because the rate of photorespiration increased with light intensity. When photorespiration was

inhibited by AAN, no decreases in peroxisomal NADPH was seen (Fig. 3g). Together, these results imply that during photorespiration, a large amount of NADH is generated in the mitochondria

through the action of GDC, and concurrently, a large amount of NADH is oxidized in the peroxisomes through the action of HPR. The cytosol is thus in the path of the flow of reducing

equivalents between chloroplasts, peroxisomes and mitochondria. The change in the cytosolic NADH/NAD+ ratio thus reflects the flow of reducing equivalents between these three organelles.

EFFECTS OF METC INHIBITORS ON THE FLOW OF REDUCING EQUIVALENTS Next, we examined the effects of mETC inhibitors, namely rotenone (complex I), TTFA (complex II), antimycin A (complex III),

KCN (cytochrome _c_-dependent respiration), and oligomycin A (ATP synthase), on the NADPH and NADH/NAD+ levels in different subcellular compartments (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Fig. 11). The

use of rotenone, TTFA, AA, KCN, and oligomycin A increased the cytosolic SoNar ratios, but DCMU and AAN had no effect (Fig. 4, Supplementary Fig. 11). This was also true for cytosolic iNAP1

(except with KCN). This indicates that when the ability of mitochondria to consume NADH in darkness is inhibited, NADH and NADPH accumulate in the cytosol. However, the use of these

inhibitors did not increase the basal NADPH level in chloroplasts, indicating that the stromal pool of NADPH in darkness is not affected by mETC activity, probably because stromal NADP-MDH

is a light-dependent enzyme. In addition, the basal level of stromal NADH/NAD+ ratio was significantly increased by rotenone application, suggesting that reducing equivalents accumulate in

the cytosol and stroma after the inhibition of complex I (Fig. 4d). Upon illumination, an increment in stromal NADPH in seedlings treated with rotenone, AA, and oligomycin A can still be

clearly seen (Fig. 4f), as these inhibitors do not inhibit the LEF in chloroplasts. However, TTFA treatment completely suppressed the accumulation of stromal NADPH upon illumination (Fig.

4f) and ETR, Y(II) and qP (Fig. 4k, m, n), probably because TTFA suppresses ferredoxin: NADP+ oxidoreductase (FNR)40, and reduced the photosynthesis rate (Supplementary Fig. 10b). In

addition, we still observed an increase in stromal NADH/NAD+ in seedlings treated with rotenone, TTFA and AA upon illumination (Fig. 4i). Surprisingly, rotenone and AA treatments resulted in

a decrease in cytosolic NADH/NAD+ ratio upon illumination (Fig. 4j), possibly due to de novo NAD+ synthesis. Furthermore, a study with the respiratory inhibitor KCN, as a mean to elucidate

the reducing equivalent dynamics in cytochrome _c_-dependent respiration, revealed that KCN treatment also completely inhibited ETR (Fig. 4k). When KCN was applied, the basal cytosolic

NADH/NAD+ ratio was higher in darkness. In the presence of KCN, whereas illumination did not increase the stromal NAPDH (Fig. 4f) or NADH/NAD+ ratio (Fig. 4i), it did increase the cytosolic

NAPDH (Fig. 4g) and NADH/NAD+ ratio (Fig. 4j). DISCUSSION Monitoring real-time subcellular dynamic changes in reducing equivalents _in planta_ has been a long-term challenge. The iNAP and

SoNar fluorescence-based sensors were initially introduced in mammalian cells to study the responsiveness of reducing equivalents in homeostasis and cancer cells in vivo3,4. SoNar is

preferred over another NADH/NAD+ sensor, Peredox-mCherry, because it has a 10-fold higher dynamic range and does not aggregate in the cytosol41. For the first time, we introduced these iNAP

and SoNar sensors into several subcellular compartments in plants (Supplementary Fig. 1). This _in planta_ imaging has resolved the bottleneck preventing the study of physiological changes

in reducing equivalents at the subcellular level, providing a valuable tool to monitor the real-time dynamics of reducing equivalents without destroying the plant tissues. We introduced two

iNAP sensors with high (iNAP1) and low (iNAP4) NADPH affinities into chloroplasts, peroxisomes and cytosol of Arabidopsis. Our data indicated that iNAP1 is more suitable for observing the

changes in cytosolic NADPH levels, whereas iNAP4 is more suitable for monitoring the changes in chloroplast and peroxisome NADPH levels, implying that the cytosolic NADPH concentration may

be lower in the cytosol than in the other two compartments. These data corroborate results from past experiments involving the rapid fractionation of illuminated barley protoplasts into

chloroplasts and cytosol, in which the total concentrations of NADP+ and NADPH were estimated to be 0.6–0.8 mM in chloroplasts and 0.25–0.35 mM in cytosol, when the NADPH/NADP+ ratios in

these two compartments (1.4 and 1.5) were similar under limiting CO2 conditions42. De novo synthesis of NADP+ in cytosol, chloroplasts, and peroxisomes is carried out by the ATP-dependent

NAD kinases: NADK1, NADK2, and NADK343, among which NADK2 in chloroplasts, is a light-dependent enzyme44. Illumination of 3-week-old plants for 5 min to 1 h gradually increases the NADP+ and

NADPH pools in the rosette leaves of WT plants but not in a _nadk2_ mutant, indicating that, under illumination, the synthesis of NADP+ from NAD+ by NADK2 in the chloroplasts is the major

NADP+ synthesis pathway. The newly synthesized NADP+ is then reduced to NADPH by FNR, and the NADPH/NADP+ ratio is maintained at ~1 in the first 5 min of illumination, and gradually

decreases to ~0.7 after 60 min of illumination44. By using iNAP sensors with different affinities, we observed not only an increase in stromal NADPH, but also a small decrease of NADPH in

the cytosol and peroxisomes upon illumination (Fig. 2). As reported previously from barley leaf protoplast experiments, the stromal NADPH/NADP+ ratio declines within 30 s in darkness after

illumination24; similarly, we observed a rapid decline in stromal NADPH and NADH/NAD+ ratio after the light was turned off (Fig. 2). The rapid decline of NADPH level in the first 30 s of

darkness can be mainly attributed to the CBB cycle, as Rubisco carboxylation stops ~30 s after light withdrawal36. After that, the decline might be mainly due to the malate-OAA shuttle. A

small amount of NADPH may also be recycled to NADP+ in the light by light-dependent glutathione reductase, but the flux is expected to be small because the substrate, GSSG, is present in the

low nanomolar range35. Although NAD+ can be transported through chloroplasts, mitochondria, and peroxisomes via NDT1, NDT245, and PXN46, organelle membranes are impermeable to NADP(H) and

NADH due to the lack of transporters. This enables the subcellular compartmentation of NADP(H) and NAD(H) and requires their indirect translocation between subcellular compartments by

shuttles, such as the malate-OAA shuttle. The operation of the malate-OAA shuttle requires the presence of various MDHs in different compartments. Arabidopsis possesses two chloroplastic

MDHs, the light-dependent NADP+-specific MDH and the light-independent NAD+-specific MDH, both of which could transfer stromal surplus reducing equivalents to malate. Our data showed that

the post-illumination decrease in stromal NADPH was slower than the drop in stromal NADH/NAD+ ratio after 30 s of darkness (Fig. 2), consistent with the natures of these two classes of

plastidic MDHs. NADPH is important for fatty acid synthesis and detoxification of oxidative stresses in chloroplasts in the light47. This may provide an explanation of why, during evolution,

two plastidic MDHs with different substrate specificity and light dependence have been maintained in the plant genomes. During photosynthesis, the surplus NADPH must be exported by the

malate-OAA shuttle and therefore requires an active NADP-MDH that functions in a light-dependent manner. In darkness, malate accumulated in the light can be converted to NADH by NAD-MDHs in

various subcellular compartments, but not by NADP-MDH to NADPH in plastids. Fundamental to our study was the question of what serves as the major source of reducing equivalents to mETC

during photosynthesis. A key insight from our AAN and NaHCO3 experiments was that in the absence of photorespiration, the increases in stromal NADPH and NADH/NAD+ upon illumination

disappeared (Fig. 3a, b, h, i), suggesting that when photorespiration fails to generate NADH in mitochondria, the mitochondrial malate-OAA shuttle can supply NADH to the mETC (Fig. 3d).

This, in turn, could indirectly draw reducing equivalents from the chloroplasts through the cytosolic malate pool and chloroplastic malate-OAA shuttle (Fig. 5). Hence, illumination upon AAN

and NaHCO3 treatments caused no increase in stromal NADPH (Fig. 3a, h). Our data imply that during photosynthesis, the amount of NADH generated by the photorespiratory GDC is higher than the

NADH-dissipating capacity of mitochondria including those of complex I, non-proton-pumping internal NADH dehydrogenases (NDA1 and NDA2), and the mETC and therefore a net export of malate is

expected. GDC is the most abundant soluble enzyme in the mitochondria of photosynthetic tissues, and GDC activity increases significantly only after the chloroplasts are mature enough to

carry out photosynthesis48. Although GDC is highly abundant, the amount of NADH generated by GDC is dependent on the size of the flux of photorespiration cycle, which is dependent on the

light intensity. When AAN or NaHCO3 were supplied, we detected no increase in stromal NADPH level (Fig. 3a, h) or NADH/NAD+ ratio (Fig. 3b, i). It has been estimated that only 5% of NADPH

generated from the LEF in chloroplasts is exported by the malate valve15. This implies that when photorespiration does not generate any NADH in mitochondria, in addition to the tricarboxylic

acid (TCA) cycle which could supply an unknown amount of reducing equivalents, the mitochondrial ETC can rely on the import of malate for NADH supply. However, under normal photorespiratory

conditions, when copious NADH is produced in mitochondria, the peroxisomes could consume NADH at a theoretical ratio of 1:1. In reality, photorespiration is also a source of serine

synthesis49, and therefore the ratio of mitochondrial NADH production and peroxisomal NADH consumption is >18. As chloroplasts also export malate, it builds up during the day, and most is

stored in the vacuole17. This indicates that at the whole-cell level, reducing equivalents accumulate during photosynthesis in the form of malate and carbohydrates. At 296 µmol m−2 s−1

illumination, the cytosolic NADH/NAD+ ratio gradually increased (Fig. 2d). Our results (Fig. 2b, e) corroborate the findings of Heineke et al.50 indicating that both stromal NADPH and NADH

pools increase upon illumination. According to Heineke et al.50, the concentrations of malate in spinach chloroplasts and cytosol plus mitochondria during darkness were both calculated as 1

mM, whereas after 8.5 h of illumination, the stromal malate concentration increased to 3 mM but the cytosolic malate concentration was unchanged. The stromal ATP level was also slightly

increased upon application of AAN under photorespiratory conditions (Fig. 3c). An increase in ATP/ADP ratio in the presence of AAN was also reported in a protoplast experiment23. Our _in

planta_ real-time findings are in agreement with previous studies on protoplasts23,24 and mitochondria27 indicating that photorespiration is the major source of reducing equivalents to the

mETC. These reports suggested that the amount of NADH generated by GDC in mitochondria exceeds the capacity of the mETC to dissipate NADH, and therefore surplus NADH generated from

photorespiration must be exported to the cytosol from the mitochondria through the malate-OAA shuttle. Several other lines of evidence support this notion. First, plants deficient in

mitochondrial MDH grow slowly51, and experiments with 13C showed an increased labeling of glycine and serine, indicating a limitation of the flux of the photorespiratory pathway52. Second,

the volume of stroma of spinach mesophyll was calculated as ~20 times the volume of mitochondria53. All the 2-PG generated in the chloroplasts has to be cycled into glycine in the

peroxisomes, and most has to be converted into serine in mitochondria during photosynthesis. Hence, the GDC activity in mitochondria, representing such a small volume of the whole cell,

during photosynthesis must be very robust. Third, GDC is the most abundant soluble protein in the mitochondria of C3 plants, comprising ~40% of the mitochondrial matrix of mature C3

plants48. The concentration of the GDC glycine-binding site is estimated at nearly 0.5 mM54, and the _k_cat of GDC is on the order of 5–10 per second (10 s−1), which is comparable to that of

Rubisco (10 s−1) but much slower than that of mitochondrial MDH (60 s−1 for the forward reaction and 1000–3000 s−1 for the reverse reaction)54. The reverse reaction of mMDH oxidizes NADH to

relieve its inhibition of GDC (_K_i = 15 µM)55 and converts OAA to malate to export the surplus NADH from photorespiration to the cytosol. Various bioenergetic processes driven by

illumination, including photosynthesis, photorespiration, fatty acid synthesis, and nitrate assimilation, drive the flux of OAA and malate between the three organelles involved in

photorespiration. These three organelles will physically adhere to each other to speed up the flux upon illumination56. In plants, the mitochondrion is the major organelle producing

cytosolic ATP2. The TCA cycle operates in a circular fashion during the dark phase27,57: reducing equivalents generated in the TCA cycle that are fed from organic acids like pyruvate and

malate58 drive the mETC to produce ATP through the mitochondrial ATP synthase26. However, during the daytime, the TCA cycle does not run as a circle27,57. This could be explained by the

presence of surplus NADH generated from GDC, as NADH serves as an inhibitor of the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex, citrate synthase, and 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase of the TCA cycle. Taken

together, our data extend current knowledge of the flow of reducing equivalents between subcellular compartments to a malate–OAA flux model (Fig. 5a). This model incorporates the following

assumptions: (1) The rate of photorespiration and LEF increase with light intensity. Assuming the fixation of CO2 and O2 occur at a 3:1 ratio6. (2) For each O2 fixed by Rubisco in the

chloroplast, 0.5 molecule of NADH is generated by the GDC in the mitochondria8. (3) The capacity of the mETC to dissipate electrons from NADH (E) through Complex I, NDA1, and NDA2 is not

instantly affected by the light intensity. (4) The amount of NADH generated from photorespiration (R), at the light intensities we tested, exceeded the capacity of the mETC (E), and the

surplus reductants (R–E) are exported by the mitochondrial malate–OAA flux. (5) Some serine generated from photorespiration leaves the photorespiration pathway (S)9, and hence the amount of

NADH consumed by HPR in the peroxisome is less than the amount of NADH generated by the GDC. (6) Around 5% of electrons generated from the LEF (L) in the form of NADPH are exported by the

malate–OAA flux from the chloroplasts (f)15. (7) Malate accumulates during photosynthesis is stored in the vacuole. The rate of malate accumulation (M) is f + S − N, where _N_ is the amount

of NADH consumed by the cytosolic nitrate reductase during nitrogen assimilation. Hence, malate is basically derived from OAA, which is synthesized from PEP (P) and whose input is also equal

to f + S − N. (8) Since LEF generates a higher NADPH/ATP ratio than the ratio consumed by the CBB, surplus NADPH is generated during photosynthesis, and though some is exported to

extrachloroplastic compartments through the malate–OAA shuttle, a build-up of stromal NADPH occurs (Fig. 2b). After photorespiration is inhibited by AAN or NaHCO3 (Fig. 5b), the following

assumptions hold: (1) Since no NADH is generated by GDC in the mitochondria (_R_ = 0), malate, instead of being exported, is imported into mitochondria to supply NADH to the mETC. (2) As the

cytosolic malate/OAA ratio decreases, the malate–OAA flux (F) of the chloroplasts increases and exports reducing equivalents from stromal NADPH at a higher rate. As a result, no increase in

NADPH concentration occurs (Fig. 3b). (3) The net synthesis of malate (m) is therefore equal to F – E – n, which is significantly smaller than the M (f + S − N) in the absence of AAN

treatment. Hence, the reversible reaction between malate and OAA helps to build up the equilibrium of reducing equivalents between subcellular compartments under light and dark conditions.

METHODS PLASMID CONSTRUCTION AND GENERATION OF PLANT LINES To construct the plant transformation vectors, the cDNAs of iNAP1, iNAP4, iNAPc, and SoNar were amplified with Platinum Pfx

polymerase (Invitrogen) from the pcDNA3.1 vectors3 and subcloned into the BamHI and XbalI restriction sites of a modified Gateway pENTR/D-TOPO vector (Invitrogen). For targeting to plastids,

peroxisomes, and mitochondria, the sequences from _Nicotiana tabacum_ chloroplast transketolase transit peptide (TKTP)59, peroxisomal targeting signal type 1 (SRL)60 or

mitochondrial-targeting sequence from _Nicotiana plumbaginifolia_ β-ATPase (MT)31 were fused to the N-terminus (TKTP and MT) or C-terminus (SRL) of the sensor proteins, respectively. Their

unfused versions were used for cytosolic targeting. The cDNAs were then transferred into the recipient plant transformation pEarleyGate100 vector61 under the control of the CaMV35S promoter.

The pEarleyGate100 vectors were transformed into _Arabidopsis thaliana_ plants (ecotype Columbia, Col-0) using the floral dip method62. Positive transformants were screened using

fluorescence microscopy (Nikon Eclipse 80i). The sensor cDNA sequences were also fused downstream to the 6xHis-tag of the pRSETb vector for protein expression in _Escherichia coli_ using the

BamHI and HindIII sites. Primer sequences are listed in Supplementary Table 1. All constructs were confirmed by nucleotide sequencing. Furthermore, WT (Col-0) seedlings carrying

pH2GW7-MT-cpYFP (mitochondrial matrix pH sensor) and pEarleyGate100-TKTP-AT1.03 (stromal MgATP2– sensor) were as previously reported2,30,63. PLANT CULTIVATION The transformed plants were

germinated and cultivated on plates containing Murashige and Skoog medium64 supplemented with 2% (w/v) sucrose and 1% (w/v) Phytagel and stratified for 2 days at 4 °C in darkness before

being transferred to a long-day condition with a photoperiod of 16 h at 120–150 µmol photon m−2 s−1 at 22 °C and 8 h in darkness at 18 °C. Unless otherwise stated, for assay purposes, all

seedlings were adapted in darkness for 1 h before image acquisition. RECOMBINANT PROTEIN EXPRESSION AND PURIFICATION _Escherichia coli_ BL21 (DE3) pLys cells carrying the pRSETb iNAP1,

iNAP4, iNAPc, and SoNar plasmids were grown in 15 ml LB medium containing 100 µg/ml carbenicillin at 37 °C until the cultures reached OD600 of 0.6. The expression of His-tagged proteins were

induced by 0.1 mM isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG), and the cells were then transferred to 18 °C for another 16 h of growth. Cells were collected by centrifugation at 4000×_g_

for 30 min at 4 °C, and the cell pellets were suspended in ice-cold buffer A (20 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, containing 0.5 M sodium chloride, 40 mM imidazole, and cOmplete protease

inhibitor cocktail (Roche)). After sonication, the lysates were fractionated by centrifugation at 16,000 × _g_ for 5 min at 4 °C. The supernatants were loaded into a 1-ml HisTrapTM FF column

(GE Healthcare) with a syringe attached to a 0.45-µm filter. After being washed with 2 column volumes of buffer A, proteins were eluted from the resin using buffer B (20 mM sodium phosphate

buffer, pH 7.4, containing 0.5 M sodium chloride and 400 mM imidazole). The recombinant proteins were then dialyzed in dialysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, and 150 mM sodium chloride)

overnight and stored at −80 °C before assay. The elutes were separated by 10% (w/v) SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie blue dye. NativeMarkTM unstained protein standard (Invitrogen) was

used as molecular weight marker. Expected molecular masses of 6xHis-tagged iNAP1, iNAP4, and iNAPc proteins were all 42.9 kDa. CONFOCAL IMAGING AND RATIOMETRIC IMAGE ANALYSIS Confocal

imaging of seedling was set up as previously described65. Imaging was performed with 5× and 40× oil-immersion lenses in multitrack mode using a Zeiss LSM710 NLO confocal microscope (Carl

Zeiss Microscopy). Plants expressing iNAP1, iNAP4, and iNAPc in various subcellular compartments were excited sequentially at 405 nm and 488 nm, and emission was detected at 520 ± 16 nm.

_R_iNAP, _R_iNAPc, and _R_SoNar represent the raw ratios of emission excited at 405 nm and 488 nm for iNAP1/4, iNAPc, and SoNar. Autofluorescence was recorded at 431–469 nm and chlorophyll

fluorescence was collected at 629–700 nm. Confocal images were processed with a custom MATLAB-based analysis suite66. The ratiometric images were analyzed on a pixel-by-pixel basis using

_x_, _y_ noise filtering, and fluorescence background subtraction was conducted based on the intensity of the cell samples not expressing sensors from the dark side of the images. Visually,

all the ratio profiles in the mesophyll were displayed in pseudocolors. iNAPc is the pH control sensor of iNAP and SoNar3. The pH-corrected ratio (normalized _R_405/488) was calculated with

the formula below, $${\mathrm{Normalized}}\,R_{\frac{{405}}{{488}}} = R_{{\mathrm{iNAP}}\,{\mathrm{or}}\,{\mathrm{SoNar}}}/R_{{\mathrm{iNAPc}}}$$ PROTOPLAST ISOLATION AND TRANSFECTION

Isolation of mesophyll protoplasts from the leaves of 28-day-old Arabidopsis plants expressing iNAP4-SRL or iNAPc-SRL was carried out as previously described67. The pBI221-mRFP-SRL plasmid

was a kind gift from Prof. Liwen Jiang of the Chinese University of Hong Kong. Recombinant plasmids were isolated using MAGEN HiPure Plasmid EF Midi Kit. DNA concentration was adjusted to

600 ng µl−1 per 5 kb of DNA. A total of 200 µl protoplast solution was mixed with 10 µl of recombinant plasmid and incubated in darkness at room temperature overnight before acquisition by

confocal microscopy. IN VITRO AND SEMI IN VIVO CHARACTERIZATION OF INAP AND SONAR To characterize the sensors, both in vitro and semi in vivo methods were adopted. To determine the in vitro

_K_d of the recombinant sensors at room temperature, NADPH, NADP+, NADH, and NAD+ nucleotides were titrated for iNAP1, iNAP4, iNAPc, and SoNar at pH 7.2, 7.5, 8.1, and 8.4, respectively.

Nucleotide concentrations were fixed at 0 µM, 2 µM, 10 µM, 25 µM, 50 µM, 100 µM, 125 µM, 250 µM, 500 µM, and 1000 µM. The purified recombinant sensor proteins were diluted in pseudocytosol

medium supplemented with 100 mM potassium gluconate, 30 mM NaCl, 25 mM MES, 25 mM HEPES, 40% sucrose, and 1 mg ml−1 (w/v) BSA (pH 7.5) to a final concentration of 0.5 µM. Each assay was

performed with 50 μl nucleotides and 50 μl protein arrayed in 96-well black plates (Corning Costar). Fluorescence characteristics of purified iNAP1, iNAP4, iNAPc, and SoNar were detected by

a multimode reader (Victor X3, PerkinElmer) with sequential dual excitation at 405 nm and 485 nm, whereas emission was detected at 520 nm. For semi in vivo experiment, 6–7-day-old seedlings

were infiltrated with 100 µM digitonin buffer supplemented with 100 µM digitonin, 100 mM potassium gluconate, 1 mM MgCl2, 5 mM EGTA, and 10 mM HEPES, and pH 7.5. Seedlings containing

cytosolic sensors were then infiltrated in the buffer with different NADPH concentrations (0 µM, 0.1 µM, 1.0 µM, 4.0 µM, 8.0 µM, 10.0 µM, 25.0 µM, 50.0 µM, 100.0 µM, and 500.0 µM for iNAP)

or a total concentration of 100 µM NADH/NAD+ of different ratios (for SoNar) in pseudocytosol medium for 5 min before imaging. RESPONSES OF SENSORS TO OXIDANTS, REDUCTANT, AND ANTIOXIDANTS

To obtain the potential redox ratios of the sensor lines in vitro and _in planta_, purified iNAP or SoNar recombinant proteins and 10-day-old seedlings were either treated with 10 mM

dithiothreitol (DTT) or oxidized with 10 mM H2O2 or 30 µM menadione. 10 mM l-ascorbic acid or 10 mM reduced glutathione were also tested via in vitro study. Purified recombinant proteins

were diluted in pseudocytosol medium as described above. Seedlings were infiltrated for 5 min in half-strength Murashige and Skoog medium with or without reagents before imaging. LIGHT

INTENSITY ANALYSIS Seedlings were cultivated as described above. To explore the effect of light intensity, seedlings were exposed to different light intensities (40 µmol m−2 s−1 or 296 µmol

m−2 s−1 using confocal microscope equipped with a halogen lamp (HAL 100 W; Philips). The light intensity of confocal microscope halogen lamp (HAL 100 W; Philips) was determined using a

Lutron LX-120 light meter (Lutron, Taipei, Taiwan) and converted into µmol m−2 s−1 using the formula as previously described68. Each step took 30 s of illumination and imaging was

immediately captured after each illumination period. After 3 min with 30 s intervals of exposure to the light, relaxation of seedlings in darkness was monitored for 4 min, during which the

images were acquired every 30 s. Light intensity response curves for compartmentalized iNAP1 and iNAP4 were normalized by iNAPc. INHIBITORS TREATMENT Ten-day-old seedlings were infiltrated

for 5 min in half-strength Murashige and Skoog medium with or without inhibitors. The following inhibitors were prepared and used to treat the seedlings in this study: inhibitors of

photosynthesis (0.02 mM DCMU), mitochondrial complex I (0.05 mM rotenone), SDH (0.1 mM TTFA), complex III (0.01 mM antimycin A), complex IV (0.5 mM KCN), mitochondrial ATP synthase (0.01 mM

oligomycin A)2, and photorespiration (18 mM AAN69 and 10 mM NaHCO370). Unless otherwise stated, after infiltration, all seedlings were incubated in the dark for 1 h before imaging. The

10-day-old pretreated seedlings were illuminated at 296 µmol m−2 s−1. DETERMINATION OF OXYGEN CONSUMPTION RATE AT ROOM TEMPERATURE Respiratory oxygen consumption and photosynthetic oxygen

evolution rate were measured with a Clark-type electrode (Oxygraph plus, Hansatech). Measurements were performed with 0.025 g of 10-day-old seedlings. Following an initial dark equilibration

of the seedlings, oxygen was measured in the dark for 4 min before the seedlings were illuminated at an intensity of 296 µmol m−2 s−1 for 3 min at room temperature and then subjected to 3

min of darkness. The consumption or evolution rate was determined for each minute interval. The oxygen levels from the fifth to sixth and eighth to ninth minutes were used to calculate the

evolution rate and consumption rate (nanomoles of O2 per second), respectively. The rate of photosynthesis was calculated as the evolution rate minus consumption rate. The respiration rate

(%) was calculated as follows, $${\mathrm{Respiration}}\,{\mathrm{rate}}\,({\mathrm{\% }}) =

\frac{{\frac{{{\mathrm{oxygen}}\,{\mathrm{consumption}}\,{\mathrm{rate}}\,({\mathrm{treated}}\,{\mathrm{seedlings}})}}{{{\mathrm{total}}\,{\mathrm{seedling}}\,{\mathrm{fresh}}\,{\mathrm{weight}}\,({\mathrm{g}})}}}}{{{\mathrm{oxygen}}\,{\mathrm{consumption}}\,{\mathrm{rate}}\,({\mathrm{untreated}}\,{\mathrm{seedlings}})}}

\times 100$$ DETERMINATION OF CHLOROPHYLL FLUORESCENCE PARAMETERS Fluorescence parameters were measured with a chlorophyll fluorometer (MAXIPAM, Heinz Walz) at room temperature. Treated

seedlings were incubated in darkness for 1 h. The fluorescence yield was then measured with actinic light at 280 µmol m−2 s−1 at interval of 30 s up to 3 min in the presence or absence of

inhibitors, and following by 4 min of darkness. The effective quantum yield (Y(II)), non-photochemical quenching (NPQ), and photochemical quenching (qP) were calculated as

[(_F_m′−_F_s)_/F_m′], [(_F_m−_F_m′)/_F_m′], and [(_F_m′−_F_s)/(_F_m′−_F_o)], respectively. DATA ANALYSIS All data are shown as the means with standard error (mean ± SEM). The collected data

were analyzed for statistical significance using analysis of variance (Tukey’s HSD) and paired _t_-test at _P_ < 0.001, _P_ < 0.01, and _P_ < 0.05 by SPSS (Version 20). REPORTING

SUMMARY Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article. DATA AVAILABILITY We declare that the main data supporting the

findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Information files. Source data are provided with this paper. Extra data are available from the corresponding

author upon request. REFERENCES * Liang, C. et al. Impacts of high ATP supply from chloroplasts and mitochondria on the leaf metabolism of _Arabidopsis thaliana_. _Front. Plant Sci._ 6, 922

(2015). PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Voon, C. P. et al. ATP compartmentation in plastids and cytosol of _Arabidopsis thaliana_ revealed by fluorescent protein sensing. _Proc.

Natl. Acad. Sci. USA_ 115, E10778–E10787 (2018). CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Tao, R. K. et al. Genetically encoded fluorescent sensors reveal dynamic regulation of NADPH metabolism. _Nat.

Methods_ 14, 720–728 (2017). CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Zhao, Y. Z. et al. SoNar, a highly responsive NAD+/NADH sensor, allows high-throughput metabolic screening of

anti-tumor agents. _Cell Metab._ 21, 777–789 (2015). CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Erb, T. J. & Zarzycki, J. A short history of RubisCO: the rise and fall (?) of

Nature’s predominant CO2 fixing enzyme. _Curr. Opin. Biotechnol._ 49, 100–107 (2018). CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Sharkey, T. D. Photorespiration. _eLS_

https://doi.org/10.1038/npg.els.0001292, (2001). * Bauwe, H., Hagemann, M. & Fernie, A. R. Photorespiration: players, partners and origin. _Trends Plant Sci._ 15, 330–336 (2010). CAS

PubMed Google Scholar * Busch, F. A., Sage, R. F. & Farquhar, G. D. Plants increase CO2 uptake by assimilating nitrogen via the photorespiratory pathway. _Nat. Plants_ 4, 46–54 (2018).

CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Abadie, C., Boex-Fontvieille, E. R., Carroll, A. J. & Tcherkez, G. In vivo stoichiometry of photorespiratory metabolism. _Nat. Plants_ 2, 15220 (2016).

CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Selinski, J. & Scheibe, R. Malate valves: old shuttles with new perspectives. _Plant Biol._ 21, 21–30 (2019). CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Allen, J. F.

Cyclic, pseudocyclic and noncyclic photophosphorylation: new links in the chain. _Trends Plant Sci._ 8, 15–19 (2003). CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Kramer, D. M. & Evans, J. R. The

importance of energy balance in improving photosynthetic productivity. _Plant Physiol._ 155, 70–78 (2011). CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Voon, C. P. & Lim, B. L. ATP translocation and

chloroplast biology. _Natl Sci. Rev._ 6, 1073–1076 (2019). Google Scholar * Scheibe, R. NADP+-malate dehydrogenase in C-3-plants - regulation and role of a light-activated enzyme. _Physiol.

Plant._ 71, 393–400 (1987). CAS Google Scholar * Fridlyand, L. E., Backhausen, J. E. & Scheibe, R. Flux control of the malate valve in leaf cells. _Arch. Biochem. Biophys._ 349,

290–298 (1998). CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Vishwakarma, A., Tetali, S. D., Selinski, J., Scheibe, R. & Padmasree, K. Importance of the alternative oxidase (AOX) pathway in regulating

cellular redox and ROS homeostasis to optimize photosynthesis during restriction of the cytochrome oxidase pathway in _Arabidopsis thaliana_. _Ann. Bot._ 116, 555–569 (2015). CAS PubMed

PubMed Central Google Scholar * Gerhardt, R., Stitt, M. & Heldt, H. W. Subcellular metabolite levels in spinach leaves - regulation of sucrose synthesis during diurnal alterations in

photosynthetic partitioning. _Plant Physiol._ 83, 399–407 (1987). CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Yoshida, K., Terashima, I. & Noguchi, K. Up-regulation of mitochondrial

alternative oxidase concomitant with chloroplast over-reduction by excess light. _Plant Cell Physiol._ 48, 606–614 (2007). CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Noguchi, K. & Yoshida, K.

Interaction between photosynthesis and respiration in illuminated leaves. _Mitochondrion_ 8, 87–99 (2008). CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Zakhartsev, M. et al. Metabolic model of central

carbon and energy metabolisms of growing _Arabidopsis thaliana_ in relation to sucrose translocation. _BMC Plant Biol._ 16, 262 (2016). PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Zhao, Y. N.

et al. Malate transported from chloroplast to mitochondrion triggers production of ROS and PCD in _Arabidopsis thaliana_. _Cell Res._ 28, 448–461 (2018). CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google

Scholar * Pastore, D., Trono, D., Laus, M. N., Di Fonzo, N. & Flagella, Z. Possible plant mitochondria involvement in cell adaptation to drought stress - a case study: durum wheat

mitochondria. _J. Exp. Bot._ 58, 195–210 (2007). CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Gardeström, P. & Wigge, B. Influence of photorespiration on ATP/ADP ratios in the chloroplasts,

mitochondria, and cytosol, studied by rapid fractionation of barley (_Hordeum vulgare_) protoplasts. _Plant Physiol._ 88, 69–76 (1988). PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Igamberdiev,

A. U., Romanowska, E. & Gardestrom, P. Photorespiratory flux and mitochondrial contribution to energy and redox balance of barley leaf protoplasts in the light and during light-dark

transitions. _J. Plant Physiol._ 158, 1325–1332 (2001). CAS Google Scholar * Cheung, C. Y., Poolman, M. G., Fell, D. A., Ratcliffe, R. G. & Sweetlove, L. J. A diel flux balance model

captures interactions between light and dark metabolism during day-night cycles in C3 and crassulacean acid metabolism leaves. _Plant Physiol._ 165, 917–929 (2014). CAS PubMed PubMed

Central Google Scholar * Gardeström, P. & Igamberdiev, A. U. The origin of cytosolic ATP in photosynthetic cells. _Physiol. Plant._ 157, 367–379 (2016). PubMed Google Scholar * Lee,

C. P., Eubel, H. & Millar, A. H. Diurnal changes in mitochondrial function reveal daily optimization of light and dark respiratory metabolism in Arabidopsis. _Mol. Cell. Proteom._ 9,

2125–2139 (2010). CAS Google Scholar * Shameer, S., Ratcliffe, R. G. & Sweetlove, L. J. Leaf energy balance requires mitochondrial respiration and export of chloroplast NADPH in the

light. _Plant Physiol._ 180, 1947–1961 (2019). CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Kumakura, N. et al. SGS3 and RDR6 interact and colocalize in cytoplasmic SGS3/RDR6-bodies. _FEBS

Lett._ 583, 1261–1266 (2009). CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Schwarzlander, M., Logan, D. C., Fricker, M. D. & Sweetlove, L. J. The circularly permuted yellow fluorescent protein cpYFP

that has been used as a superoxide probe is highly responsive to pH but not superoxide in mitochondria: implications for the existence of superoxide ‘flashes’. _Biochem. J._ 437, 381–387

(2011). PubMed Google Scholar * Logan, D. C. & Leaver, C. J. Mitochondria-targeted GFP highlights the heterogeneity of mitochondrial shape, size and movement within living plant cells.

_J. Exp. Bot._ 51, 865–871 (2000). CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Zhao, Y. Z. et al. In vivo monitoring of cellular energy metabolism using SoNar, a highly responsive sensor for NAD(+)/NADH

redox state. _Nat. Protoc._ 11, 1345–1359 (2016). CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Igamberdiev, A. U. & Gardestrom, P. Regulation of NAD- and NADP-dependent isocitrate dehydrogenases by

reduction levels of pyridine nucleotides in mitochondria and cytosol of pea leaves. _Biochim. Biophys. Acta_ 117–125, 1606 (2003). Google Scholar * Igamberdiev, A. U., Bykova, N. V., Lea,

P. J. & Gardestrom, P. The role of photorespiration in redox and energy balance of photosynthetic plant cells: a study with a barley mutant deficient in glycine decarboxylase. _Physiol.

Plant._ 111, 427–438 (2001). CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Foyer, C. H. & Noctor, G. Ascorbate and glutathione: the heart of the redox hub. _Plant Physiol._ 155, 2–18 (2011). CAS

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Bassham, J. A., Shibata, K., Steenberg, K., Bourdon, J. & Calvin, M. The Photosynthetic cycle and respiration: light-dark transients. _J. Am.

Chem. Soc._ 78, 4120–4124 (1956). CAS Google Scholar * Berkemeyer, M., Scheibe, R. & Ocheretina, O. A novel, non-redox-regulated NAD-dependent malate dehydrogenase from chloroplasts of

_Arabidopsis thaliana_ L. _J. Biol. Chem._ 273, 27927–27933 (1998). CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Engel, N. et al. Deletion of glycine decarboxylase in Arabidopsis is lethal under

nonphotorespiratory conditions. _Plant Physiol._ 144, 1328–1335 (2007). CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Gardestrom, P., Bergman, A. & Ericson, I. Inhibition of the

conversion of glycine to serine in spinach leaf mitochondria. _Physiol. Plant._ 53, 439–444 (1981). Google Scholar * Ikezawa, N., Ifuku, K., Endo, T. & Sato, F. Inhibition of

photosystem II of spinach by the respiration inhibitors piericidin A and thenoyltrifluoroacetone. _Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem._ 66, 1925–1929 (2002). CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Zhao, Y.

Z. & Yang, Y. Real-time and high-throughput analysis of mitochondrial metabolic states in living cells using genetically encoded NAD+/NADH sensors. _Free Radic. Biol. Med._ 100, 43–52

(2016). CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Wigge, B., Kromer, S. & Gardestrom, P. The redox levels and subcellular-distribution of pyridine-nucleotides in illuminated barley leaf protoplasts

studied by rapid fractionation. _Physiol. Plant._ 88, 10–18 (1993). CAS Google Scholar * Hashida, S. & Kawai-Yamada, M. Inter-organelle NAD metabolism underpinning light responsive

NADP dynamics in plants. _Front. Plant Sci._ 10, 960 (2019). PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Hashida, S. et al. Ferredoxin/thioredoxin system plays an important role in the

chloroplastic NADP status of Arabidopsis. _Plant J._ 95, 947–960 (2018). CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Palmieri, F. et al. Molecular identification and functional characterization of

_Arabidopsis thaliana_ mitochondrial and chloroplastic NAD+ carrier proteins. _J. Biol. Chem._ 284, 31249–31259 (2009). CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Bernhardt, K.,

Wilkinson, S., Weber, A. P. M. & Linka, N. A peroxisomal carrier delivers NAD plus and contributes to optimal fatty acid degradation during storage oil mobilization. _Plant J._ 69, 1–13

(2012). CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Marty, L. et al. Arabidopsis glutathione reductase 2 is indispensable in plastids, while mitochondrial glutathione is safeguarded by additional

reduction and transport systems. _New Phytol._ 224, 1569–1584 (2019). CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Vauclare, P., Diallo, N., Bourguignon, J., Macherel, D. & Douce, R. Regulation of the

expression of the glycine decarboxylase complex during pea leaf development. _Plant Physiol._ 112, 1523–1530 (1996). CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Ros, R., Munoz-Bertomeu,

J. & Krueger, S. Serine in plants: biosynthesis, metabolism, and functions. _Trends Plant Sci._ 19, 564–569 (2014). CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Heineke, D. et al. Redox transfer

across the inner chloroplast envelope membrane. _Plant Physiol._ 95, 1131–1137 (1991). CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Tomaz, T. et al. Mitochondrial malate dehydrogenase

lowers leaf respiration and alters photorespiration and plant growth in Arabidopsis. _Plant Physiol._ 154, 1143–1157 (2010). CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Lindén, P., Keech,

O., Stenlund, H., Gardeström, P. & Moritz, T. Reduced mitochondrial malate dehydrogenase activity has a strong effect on photorespiratory metabolism as revealed by 13C labelling. _J.

Exp. Bot._ 67, 3123–3135 (2016). PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Winter, H., Robinson, D. G. & Heldt, H. W. Subcellular volumes and metabolite concentrations in spinach leaves.

_Planta_ 193, 530–535 (1994). CAS Google Scholar * Bykova, N. V., Moller, I. M., Gardestrom, P. & Igamberdiev, A. U. The function of glycine decarboxylase complex is optimized to

maintain high photorespiratory flux via buffering of its reaction products. _Mitochondrion_ 19, 357–364 (2014). CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Oliver, D. J. & Raman, R. Glycine

decarboxylase - protein chemistry and molecular-biology of the major protein in leaf mitochondria. _J. Bioenerg. Biomembr._ 27, 407–414 (1995). CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Oikawa, K. et

al. Physical interaction between peroxisomes and chloroplasts elucidated by in situ laser analysis. _Nat. Plants_ 1, 15035 (2015). CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Sweetlove, L. J., Beard, K.

F., Nunes-Nesi, A., Fernie, A. R. & Ratcliffe, R. G. Not just a circle: flux modes in the plant TCA cycle. _Trends Plant Sci._ 15, 462–470 (2010). CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Lehmann,

M. M. et al. Metabolic fate of the carboxyl groups of malate and pyruvate and their Influence on delta C-13 of leaf-respired CO2 during light enhanced dark respiration. _Front. Plant Sci._

7, 739 (2016). PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Schwarzlander, M. et al. Confocal imaging of glutathione redox potential in living plant cells. _J. Microsc._ 231, 299–316 (2008).

MathSciNet CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Hayashi, M., Aoki, M., Kondo, M. & Nishimura, M. Changes in targeting efficiencies of proteins to plant microbodies caused by amino acid

substitutions in the carboxy-terminal tripeptide. _Plant Cell Physiol._ 38, 759–768 (1997). CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Earley, K. W. et al. Gateway-compatible vectors for plant

functional genomics and proteomics. _Plant J._ 45, 616–629 (2006). CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Clough, S. J. & Bent, A. F. Floral dip: a simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated

transformation of _Arabidopsis thaliana_. _Plant J._ 16, 735–743 (1998). CAS PubMed Google Scholar * De Col, V. et al. ATP sensing in living plant cells reveals tissue gradients and

stress dynamics of energy physiology. _eLife_ 6, 26770 (2017). Google Scholar * Murashige, T. & Skoog, F. A revised medium for rapid growth and bio assays with tobacco tissue cultures.

_Physiol. Plant._ 15, 473–497 (1962). CAS Google Scholar * Wagner, S. et al. Analysis of plant mitochondrial function using fluorescent protein sensors. _Methods Mol. Biol._ 1305, 241–252

(2015). CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Fricker, M. D. Quantitative redox imaging software. _Antioxid. Redox Signal._ 24, 752–762 (2016). CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Yoo, S. D., Cho, Y. H.

& Sheen, J. Arabidopsis mesophyll protoplasts: a versatile cell system for transient gene expression analysis. _Nat. Protoc._ 2, 1565–1572 (2007). CAS PubMed Google Scholar *

Langhans R. W., Tibbitts T. _Plant Growth Chamber Handbook_. (Iowa State University, 1997). * Usuda, H., Arron, G. P. & Edwards, G. E. Inhibition of glycine decarboxylation by

aminoacetonitrile and its effect on photosynthesis in wheat. _J. Exp. Bot._ 31, 1477–1483 (1980). CAS Google Scholar * Gardeström, P. Adenylate ratios in the cytosol, chloroplasts and

mitochondria of barley leaf protoplasts during photosynthesis at different carbon-dioxide concentrations. _FEBS Lett._ 212, 114–118 (1987). Google Scholar Download references

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This project was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31870212), the Seed Funding Program for Basic Research (201811159131), the Hong Kong Research

Grants Council Area of Excellence Scheme (AoE/M-403/16), and the Innovation and Technology Fund (Funding Support to State Key Laboratory of Agrobiotechnology) of the HKSAR, China. Any

opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this publication do not reflect the views of the Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region or the Innovation

and Technology Commission.” AUTHOR INFORMATION AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * School of Biological Sciences, University of Hong Kong, Pokfulam, Hong Kong, China Shey-Li Lim, Chia Pao Voon,

Xiaoqian Guan & Boon Leong Lim * Synthetic Biology and Biotechnology Laboratory, State Key Laboratory of Bioreactor Engineering, Shanghai Collaborative Innovation Center for

Biomanufacturing Technology, East China University of Science and Technology, Shanghai, China Yi Yang * Umeå Plant Science Centre, Department of Plant Physiology, Umeå University, SE-901 87,

Umeå, Sweden Per Gardeström * State Key Laboratory of Agrobiotechnology, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China Boon Leong Lim * HKU Shenzhen Institute of Research and

Innovation, Shenzhen, China Boon Leong Lim Authors * Shey-Li Lim View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Chia Pao Voon View author publications

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Xiaoqian Guan View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Yi Yang View author

publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Per Gardeström View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Boon Leong

Lim View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CONTRIBUTIONS B.L.L. and S.L.L. designed the study. C.P.V. generated and characterized the ATP and pH

sensor lines. X.G. generated the iNAP sensor constructs. S.L.L. produced the transgenic iNAP and SoNar sensor lines and carried out all the experiments. Y.Y. contributed to data analysis.

B.L.L., S.L.L., and P.G. wrote the manuscript. All authors revised and approved the manuscript. CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to Boon Leong Lim. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing interests. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION PEER REVIEW INFORMATION _Nature Communications_ thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review

of this work. PUBLISHER’S NOTE Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION SUPPLEMENTARY

INFORMATION REPORTING SUMMARY SOURCE DATA SOURCE DATA RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS OPEN ACCESS This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which

permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to

the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless

indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or

exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Reprints

and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Lim, SL., Voon, C.P., Guan, X. _et al._ _In planta_ study of photosynthesis and photorespiration using NADPH and NADH/NAD+ fluorescent

protein sensors. _Nat Commun_ 11, 3238 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-17056-0 Download citation * Received: 10 January 2020 * Accepted: 09 June 2020 * Published: 26 June 2020 *

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-17056-0 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is

not currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative