Play all audios:

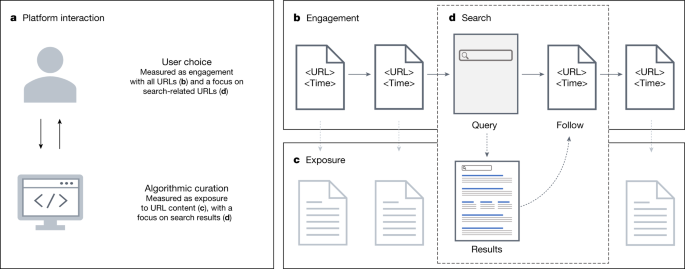

ABSTRACT If popular online platforms systematically expose their users to partisan and unreliable news, they could potentially contribute to societal issues such as rising political

polarization1,2. This concern is central to the ‘echo chamber’3,4,5 and ‘filter bubble’6,7 debates, which critique the roles that user choice and algorithmic curation play in guiding users

to different online information sources8,9,10. These roles can be measured as exposure, defined as the URLs shown to users by online platforms, and engagement, defined as the URLs selected

by users. However, owing to the challenges of obtaining ecologically valid exposure data—what real users were shown during their typical platform use—research in this vein typically relies

on engagement data4,8,11,12,13,14,15,16 or estimates of hypothetical exposure17,18,19,20,21,22,23. Studies involving ecological exposure have therefore been rare, and largely limited to

social media platforms7,24, leaving open questions about web search engines. To address these gaps, we conducted a two-wave study pairing surveys with ecologically valid measures of both

exposure and engagement on Google Search during the 2018 and 2020 US elections. In both waves, we found more identity-congruent and unreliable news sources in participants’ engagement

choices, both within Google Search and overall, than they were exposed to in their Google Search results. These results indicate that exposure to and engagement with partisan or unreliable

news on Google Search are driven not primarily by algorithmic curation but by users’ own choices. Access through your institution Buy or subscribe This is a preview of subscription content,

access via your institution ACCESS OPTIONS Access through your institution Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription $29.99

/ 30 days cancel any time Learn more Subscribe to this journal Receive 51 print issues and online access $199.00 per year only $3.90 per issue Learn more Buy this article * Purchase on

SpringerLink * Instant access to full article PDF Buy now Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout ADDITIONAL ACCESS OPTIONS: * Log in * Learn about

institutional subscriptions * Read our FAQs * Contact customer support SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS LIKE-MINDED SOURCES ON FACEBOOK ARE PREVALENT BUT NOT POLARIZING Article Open

access 27 July 2023 IDENTITY EFFECTS IN SOCIAL MEDIA Article 10 November 2022 EXPOSURE TO UNTRUSTWORTHY WEBSITES IN THE 2020 US ELECTION Article 13 April 2023 DATA AVAILABILITY Owing to

privacy concerns and IRB limitations, visit-level data will not be released, but aggregated data are available at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/WANAX3. The domain scores and classifications we

used are available at https://github.com/gitronald/domains, but the NewsGuard classifications are not included because of their proprietary nature. CODE AVAILABILITY The data for this study

were collected using custom browser extensions written in JavaScript and using the WebExtension framework for cross-browser compatibility. The source code for the extensions we used in 2018

and 2020 is available at https://github.com/gitronald/webusage, and a replication package for our results is available at https://github.com/gitronald/google-exposure-engagement. The parser

we used to extract the URLs our participants were exposed to while searching is available at https://github.com/gitronald/WebSearcher. Analyses were performed with Python v.3.10.4, pandas

v.1.4.3, scipy v.1.8.1, Spark v.3.1 and R v.4.1. REFERENCES * Wagner, C. et al. Measuring algorithmically infused societies. _Nature_ 595, 197–204 (2021). Article ADS CAS PubMed Google

Scholar * Rahwan, I. et al. Machine behaviour. _Nature_ 568, 477–486 (2019). Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Sunstein, C. R. _Republic.com_ (Princeton Univ. Press, 2001). *

Cinelli, M., De Francisci Morales, G., Galeazzi, A., Quattrociocchi, W. & Starnini, M. The echo chamber effect on social media. _Proc. Natl Acad. Sci._ 118, e2023301118 (2021). Article

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Lewandowsky, S., Ecker, U. K. H. & Cook, J. Beyond misinformation: understanding and coping with the ‘post-truth’ era. _J. Appl. Res. Mem.

Cogn._ 6, 353–369 (2017). Article Google Scholar * Pariser, E. _The Filter Bubble: What the Internet is Hiding From You_ (Penguin, 2011). * Bakshy, E., Messing, S. & Adamic, L. A.

Exposure to ideologically diverse news and opinion on Facebook. _Science_ 348, 1130–1132 (2015). Article ADS MathSciNet CAS PubMed MATH Google Scholar * Cardenal, A. S.,

Aguilar-Paredes, C., Galais, C. & Pérez-Montoro, M. Digital technologies and selective exposure: how choice and filter bubbles shape news media exposure. _Int. J. Press/Politics_ 24,

465–486 (2019). Article Google Scholar * Fletcher, R., Kalogeropoulos, A. & Nielsen, R. K. More diverse, more politically varied: how social media, search engines and aggregators shape

news repertoires in the United Kingdom. _New Media & Society_ https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448211027393 (2021). * Ekström, A. G., Niehorster, D. C. & Olsson, E. J. Self-imposed

filter bubbles: selective attention and exposure in online search. _Comput. Hum. Behav. Reports_ https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chbr.2022.100226 (2022). * Hosseinmardi, H. et al. Examining the

consumption of radical content on YouTube. _Proc. Natl Acad. Sci._ 118, e2101967118 (2021). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Chen, W., Pacheco, D., Yang, K.-C. &

Menczer, F. Neutral bots probe political bias on social media. _Nat. Commun._ 12, 5580 (2021). Article ADS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Guess, A. M., Nyhan, B. & Reifler,

J. Exposure to untrustworthy websites in the 2016 US election. _Nat. Hum. Behav._ 4, 472–480 (2020). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Allen, J., Howland, B., Mobius, M.,

Rothschild, D. & Watts, D. J. Evaluating the fake news problem at the scale of the information ecosystem. _Sci. Adv._ 6, eaay3539 (2020). Article ADS PubMed PubMed Central Google

Scholar * Muise, D. et al. Quantifying partisan news diets in Web and TV audiences. _Sci. Adv._ 8, eabn0083 (2022). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Garimella, K., Smith,

T., Weiss, R. & West, R. Political polarization in online news consumption. _Proc. International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media_ 15, 152–162 (2021). Article Google Scholar *

Hannak, A. et al. Measuring personalization of web search. In _Proc. 22nd International Conference on World Wide Web_, 527–538 https://doi.org/10.1145/2488388.2488435 (ACM, 2013). * Metaxa,

D., Park, J. S., Landay, J. A. & Hancock, J. Search media and elections: a longitudinal investigation of political search results. _Proceedings of the ACM on Human–Computer Interaction_

3, 129 (2019). Article Google Scholar * Robertson, R. E. et al. Auditing partisan audience bias within Google Search. _Proc. ACM on Human–Computer Interaction_ 2, 148 (2018). Article

Google Scholar * Trielli, D. & Diakopoulos, N. Partisan search behavior and Google results in the 2018 U.S. midterm elections. _Inf. Commun. Soc._ 25, 145–161 (2020). Article Google

Scholar * Fischer, S., Jaidka, K. & Lelkes, Y. Auditing local news presence on Google News. _Nat. Hum. Behav._ 4, 1236–1244 (2020). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Kawakami, A.,

Umarova, K. & Mustafaraj, E. The media coverage of the 2020 US presidential election candidates through the lens of Google’s top stories. In _Proc. International AAAI Conference on Web

and Social Media_ 14, 868–877 (AAAI, 2020). * Grinberg, N., Joseph, K., Friedland, L., Swire-Thompson, B. & Lazer, D. Fake news on Twitter during the 2016 U.S. presidential election.

_Science_ 363, 374–378 (2019). Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Huszár, F. et al. Algorithmic amplification of politics on Twitter. _Proc. Natl Acad. Sci._ 119, e2025334119

(2022). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Lazer, D. M. J. et al. The science of fake news. _Science_ 359, 1094–1096 (2018). Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Watts, D. J.,

Rothschild, D. M. & Mobius, M. Measuring the news and its impact on democracy. _Proc. Natl Acad. Sci._ 118, e1912443118 (2021). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar *

Gillespie, T. The politics of ‘platforms’. _New Media & Society_ 12, 347–364 (2010). Article Google Scholar * Taber, C. S. & Lodge, M. Motivated skepticism in the evaluation of

political beliefs. _Am. J. Political Sci._ 50, 755–769 (2006). Article Google Scholar * Iyengar, S. & Hahn, K. S. Red media, blue media: evidence of ideological selectivity in media

use. _J. Commun._ 59, 19–39 (2009). Article Google Scholar * Introna, L. D. & Nissenbaum, H. Shaping the web: why the politics of search engines matters. _The Information Society_ 16,

169–185 (2000). Article Google Scholar * Lawrence, S. & Giles, C. L. Accessibility of information on the web. _Nature_ 400, 107–107 (1999). Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar *

Metaxas, P. T. & DeStefano, J. Web spam, propaganda and trust. In _Proc. 2005 World Wide Web Conference_ (2005). * Vaidhyanathan, S. _The Googlization of Everything (And Why We Should

Worry)_ (Univ. of California Press, 2011). * Allcott, H. & Gentzkow, M. Social media and fake news in the 2016 election. _J. Econ. Perspect._ 31, 211–236 (2017). Article Google Scholar

* Newman, N., Fletcher, R., Kalogeropoulos, A. & Neilsen, R. K. _Digital News Report 2019_ (Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, 2019). * Mitchell, A., Gottfried, J.,

Shearer, E. & Lu, K. _How Americans Encounter, Recall and Act Upon Digital News_ (Pew Research Center, 2017). * Edelman. _Edelman Trust Barometer 2021_ (2021). * Golebiewski, M. &

Boyd, D. _Data Voids: Where Missing Data can Easily be Exploited_ (Data & Society, 2019). * Tripodi, F. _Searching for Alternative Facts: Analyzing Scriptural Inference in Conservative

News Practices_ (Data & Society, 2018). * Epstein, R. & Robertson, R. E. The search engine manipulation effect (SEME) and its possible impact on the outcomes of elections. _Proc.

Natl Acad. Sci._ 112, E4512–E4521 (2015). Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Epstein, R., Robertson, R. E., Lazer, D. & Wilson, C. Suppressing the search engine

manipulation effect (SEME). _Proc. ACM on Human–Computer Interaction_ 1, 42 (2017). Article Google Scholar * Wojcieszak, M., Menchen-Trevino, E., Goncalves, J. F. F. & Weeks, B.

Avenues to news and diverse news exposure online: comparing direct navigation, social media, news aggregators, search queries, and article hyperlinks. _Int. J. Press/Politics_ 27, 860–886

(2022); https://doi.org/10.1177/19401612211009160. * Peterson, E., Goel, S. & Iyengar, S. Partisan selective exposure in online news consumption: evidence from the 2016 presidential

campaign. _Political Sci. Res. Methods_ 9, 242–258 (2021). Article Google Scholar * Guess, A. M., Nagler, J. & Tucker, J. Less than you think: prevalence and predictors of fake news

dissemination on Facebook. _Sci. Adv._ 5, eaau4586 (2019). Article ADS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Yin, L. Local news dataset. _Zenodo_ https://doi.org/10.5281/ZENODO.1345145

(2018). * Rating Process and Criteria. _NewsGuard_ https://www.newsguardtech.com/ratings/rating-process-criteria/ (2021). * Mustafaraj, E., Lurie, E. & Devine, C. The case for

voter-centered audits of search engines during political elections. In _Proc. 2020 Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency_ 559–569 (ACM, 2020). * van Hoof, M., Meppelink,

C. S., Moeller, J. & Trilling, D. Searching differently? How political attitudes impact search queries about political issues. _New Media & Society_

https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448221104405 (2022). * Zuckerman, E. Why study media ecosystems? _Inf. Commun. Soc._ 24, 1495–1513 (2021). Article Google Scholar * Hobbs, W. R. Text scaling

for open-ended survey responses and social media posts. _SSRN_ https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3044864 (2019). * Flaxman, S., Goel, S. & Rao, J. M. Filter bubbles, echo chambers, and online

news consumption. _Public Opin. Q._ 80, 298–320 (2016). Article Google Scholar * Klar, S. & Krupnikov, Y. _Independent Politics: How American Disdain for Parties Leads to Political

Inaction_ (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2016). * Noble, S. U. _Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism_ (New York Univ. Press, 2018). * Guess, A. M., Barberá, P., Munzert, S.

& Yang, J. The consequences of online partisan media. _Proc. Natl Acad. Sci._ 118, e2013464118 (2021). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Kobayashi, T., Taka, F.

& Suzuki, T. Can ‘Googling’ correct misbelief? Cognitive and affective consequences of online search. _PLoS ONE_ 16, e0256575 (2021). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

* Gillespie, T. Algorithmically recognizable: Santorum’s Google problem, and Google’s Santorum problem. _Inf. Commun. Soc._ 20, 63–80 (2017). Article Google Scholar * Diakopoulos, N.

Algorithmic accountability: journalistic investigation of computational power structures. _Digit. Journal._ 3, 398–415 (2015). Google Scholar * Parry, D. A. et al. A systematic review and

meta-analysis of discrepancies between logged and self-reported digital media use. _Nat. Hum. Behav._ 5, 1535–1547 (2021). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Walker, M. Americans favor

mobile devices over desktops and laptops for getting news. _Pew Research Center_

https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2019/11/19/americans-favor-mobile-devices-over-desktops-and-laptops-for-getting-news/ (2019). * Trielli, D. & Diakopoulos, N. Search as news

curator: the role of Google in shaping attention to news information. In _Proc. 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems_ https://doi.org/10.1145/3290605.3300683 (ACM Press,

2019). * Nanz, A. & Matthes, J. Democratic consequences of incidental exposure to political information: a meta-analysis. _J. Commun._ 72, 345–373 (2022). Article Google Scholar *

Bechmann, A. & Nielbo, K. L. Are we exposed to the same ‘news’ in the news feed? An empirical analysis of filter bubbles as information similarity for Danish Facebook users. _Digit.

Journal._ 6, 990–1002 (2018). Google Scholar * Guess, A. M. (Almost) everything in moderation: new evidence on Americans’ online media diets. _Am. J. Political Sci._ 65, 1007–1022 (2021).

Article Google Scholar * Reeves, B. et al. Screenomics: a framework to capture and analyze personal life experiences and the ways that technology shapes them. _Hum. Comput. Interact._ 36,

150–201 (2021). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Stier, S., Mangold, F., Scharkow, M. & Breuer, J. Post post-broadcast democracy? News exposure in the age of online intermediaries.

_Am. Political Sci. Rev._ 116, 768–774 (2021). Article Google Scholar * Pan, B. et al. In Google we trust: users’ decisions on rank, position, and relevance. _J. Comput.-Mediat. Commun._

12, 801–823 (2007). Article Google Scholar * Kulshrestha, J. et al. Search bias quantification: investigating political bias in social media and web search. _Inf. Retr. J._ 22, 188–227

(2019). Article MathSciNet Google Scholar * Joachims, T. et al. Evaluating the accuracy of implicit feedback from clicks and query reformulations in Web search. _ACM Trans. Inf. Syst._

25, 7–es (2007). Article Google Scholar * Ebbinghaus, H. _Memory: A Contribution to Experimental Psychology_ https://doi.org/10.1037/10011-000 (Teachers College Press, 1913). * Fishkin, R.

New jumpshot 2018 data: where searches happen on the web (Google, Amazon, Facebook, & beyond). _SparkToro_

https://sparktoro.com/blog/new-jumpshot-2018-data-where-searches-happen-on-the-web-google-amazon-facebook-beyond/ (2018). * Desktop search engine market share United States of America.

_StatCounter Global Stats_ https://gs.statcounter.com/search-engine-market-share/desktop/united-states-of-america/2020 (2020). * Brown, N. E. Political participation of women of color: an

intersectional analysis. _J. Women Polit. Policy_ 35, 315–348 (2014). Article Google Scholar * Hyde, J. S., Bigler, R. S., Joel, D., Tate, C. C. & van Anders, S. M. The future of sex

and gender in psychology: five challenges to the gender binary. _Am. Psychol._ 74, 171–193 (2019). Article PubMed Google Scholar Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Early versions of

this work were presented at the 2019 International Conference on Computational Social Science (IC2S2), the 2019 Conference on Politics and Computational Social Science (PaCCS) and the 2020

annual meeting of the American Political Science Association (APSA). We are grateful to the New York University Social Media and Political Participation (SMaPP) lab, the Stanford Internet

Observatory and the Stanford Social Media Lab for feedback, and to Muhammad Ahmad Bashir for development on the 2018 extension. This research was supported in part by the Democracy Fund, the

William and Flora Hewlett Foundation and the National Science Foundation (IIS-1910064). AUTHOR INFORMATION AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Stanford University, Stanford Internet Observatory,

Stanford, CA, USA Ronald E. Robertson * Northeastern University, Network Science Institute, Boston, MA, USA Ronald E. Robertson, Jon Green, Damian J. Ruck, Christo Wilson & David Lazer *

Rutgers University, School of Communication & Information, New Brunswick, NJ, USA Katherine Ognyanova * Northeastern University, Khoury College of Computer Sciences, Boston, USA Christo

Wilson Authors * Ronald E. Robertson View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Jon Green View author publications You can also search for this

author inPubMed Google Scholar * Damian J. Ruck View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Katherine Ognyanova View author publications You can

also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Christo Wilson View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * David Lazer View author

publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CONTRIBUTIONS R.E.R., C.W. and D.L. conceived of the research. K.O., C.W., D.L. and R.E.R. contributed to survey

design. R.E.R. built the 2020 data collection instrument. J.G. designed the multivariate regression analysis. R.E.R. and J.G. analysed the data and R.E.R. wrote the paper with D.J.R., J.G.,

K.O., C.W. and D.L. All authors approved the final manuscript. CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to Ronald E. Robertson. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS The authors declare no

competing interests. PEER REVIEW PEER REVIEW INFORMATION _Nature_ thanks Homa Hosseinmardi and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer

reviewer reports are available. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION PUBLISHER’S NOTE Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

EXTENDED DATA FIGURES AND TABLES EXTENDED DATA FIG. 1 STRONG PARTISANS ARE EXPOSED TO SIMILAR RATES OF PARTISAN AND UNRELIABLE NEWS, BUT ASYMMETRICALLY FOLLOW AND ENGAGE WITH SUCH NEWS.

This figure complements Fig. 1 in the main text by displaying, for all 7-point PID groups, average exposure, follows and overall engagement with partisan (A, C) and unreliable news (B, D) by

study wave and 7-point PID clustered at the participant-level. Data are presented as participant-level means grouped by 7-point PID in each subplot, all error bars indicate 95% confidence

intervals (CI), and results from bivariate tests of differences in partisan and unreliable news by 7-point PID are available in Extended Data Table 2. A score of zero does not imply

neutrality in the scores we used, so left-of-zero scores do not imply a left-leaning bias (Methods, ‘Partisan News Scores’). EXTENDED DATA FIG. 2 PARTISANS WHO ENGAGE WITH MORE

IDENTITY-CONGRUENT NEWS ALSO TEND TO ENGAGE WITH MORE UNRELIABLE NEWS. This figure complements Fig. 3 in the main text by displaying all 7-point PID groups, highlighting the relationship

between partisan and unreliable news for participants’ exposure on Google Search (A, D), follows from Google Search (B, E), and overall engagement (C, F). These subplots show that the

relationship between partisan and unreliable news varies across data types, and within data types when taking partisan identity into account (Extended Data Table 3). EXTENDED DATA FIG. 3

PARTISAN NEWS DISTRIBUTIONS AT THE PARTICIPANT LEVEL FOR EACH DATASET AND STUDY WAVE. Each line represents the distribution of partisan news sources that a single participant was exposed to

in their Google Search results (A, D), followed from those results (B, E), or engaged with overall (C, F). Partisan news scores have been binned in 0.1 point intervals (e.g. −1 to −0.9, −0.9

to −0.8, etc.) along the x-axis, with tick labels showing the midpoints of those bins. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION This file contains text that introduces several

Supplementary Information tables and provides our IRB study procedures. The Supplementary Information tables include extensive demographics for each study (Supplementary Information Tables 1

and 2), example news domains and their partisan audience bias scores (Supplementary Information Table 3), comparisons of participants’ popular search engine usage (Supplementary Information

Table 4), participant-level averages for each dataset in each study wave (Supplementary Information Table 5), the average proportion of news and unreliable news we found in each dataset and

study wave (Supplementary Information Table 6) and detailed results for each of the regressions we ran (Supplementary Information Tables 7–18). REPORTING SUMMARY PEER REVIEW FILE RIGHTS AND

PERMISSIONS Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other

rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law. Reprints and

permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Robertson, R.E., Green, J., Ruck, D.J. _et al._ Users choose to engage with more partisan news than they are exposed to on Google Search.

_Nature_ 618, 342–348 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06078-5 Download citation * Received: 17 February 2022 * Accepted: 12 April 2023 * Published: 24 May 2023 * Issue Date: 08

June 2023 * DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06078-5 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a

shareable link is not currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative