Play all audios:

ABSTRACT The clinical criteria for the diagnosis of urticarial vasculitis lack accuracy, according to previous studies. The aim of the study was to assess the accuracy of a clinical and a

clinical-dermoscopic model for the differential diagnosis of chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU) and urticarial vasculitis (UV). Dermoscopic images of lesions with histopathologically

confirmed diagnosis of CSU and UV were evaluated for the presence of selected criteria (purpuric patches/globules (PG) and red linear vessels). Clinical criteria of CSU and UV were also

registered. Univariate and adjusted odds ratios were calculated. Multivariate regression analyses were conducted separately for clinical variables (clinical diagnostic model) and for both

clinical and dermoscopic variables (clinical-dermoscopic diagnostic model). 108 patients with CSU and 27 patients with UV were included in the study. The clinical-dermoscopic model notably

showed higher diagnostic sensitivity than the clinical approach (63% vs. 44%). Dermoscopic purpuric patches/globules (PG) was the variable that better discriminated UV, increasing by 19-fold

the odds for this diagnosis. In conclusion, dermoscopy helps the clinical discrimination between CSU and UV. The visualization of dermoscopic PG may contribute to optimize decisions

regarding biopsy in patients with urticarial rashes. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS UTILITY OF C3D AND C4D IMMUNOHISTOCHEMICAL STAINING IN FORMALIN-FIXED SKIN OR MUCOSAL BIOPSY

SPECIMENS IN DIAGNOSIS OF BULLOUS PEMPHIGOID AND MUCOUS MEMBRANE PEMPHIGOID Article Open access 12 July 2023 A SIMPLE NOMOGRAM FOR ASSESSING THE RISK OF IGA VASCULITIS NEPHRITIS IN IGA

VASCULITIS ASIAN PEDIATRIC PATIENTS Article Open access 07 October 2022 MATHEMATICAL-BASED MORPHOLOGICAL CLASSIFICATION OF SKIN ERUPTIONS CORRESPONDING TO THE PATHOPHYSIOLOGICAL STATE OF

CHRONIC SPONTANEOUS URTICARIA Article Open access 04 December 2023 INTRODUCTION Urticarial vasculitis (UV) is a clinicopathologic entity characterized by urticarial lesions disclosing

histopathologically leukocytoclastic vasculitis, mainly of postcapillary venules1,2. Recognizing UV is crucial given a possible association with systemic features. UV is classified into

hypocomplementemic (HUV) and normocomplementemic (NUV). HUV is a rare systemic vasculitis, showing urticarial lesions and systemic manifestations, such as arthritis/arthralgia,

glomerulonephritis, uveitis, recurrent abdominal pain or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. More than half of patients have associated anti-C1q antibodies2. In contrast, NUV, is a

skin-limited vasculitis1,2. UV may be associated to autoimmune connective tissue diseases, infections, drugs or neoplasia, although most of the cases are idiopathic3,4. UV is a rare

condition, clinically overlapping with the more common chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU). It is noteworthy that lesions of CSU and UV may be visually indistinguishable, and often represent

a real diagnostic challenge for the clinician5. A definitive diagnosis of UV requires a skin biopsy, which is performed when UV is suspected due to the presence of four classic clinical

criteria: persistence of individual lesions, lasting more than 24 hours; presence of tenderness or a painful/burning sensation; purpura or dusky discoloration of the skin and resolution of

lesions with residual hyperpigmentation6. The accuracy of this clinical approach has been questioned, as some studies have demonstrated absence of these features in a significant proportion

of patients with UV4,5,6,7,8,9. Furthermore, even the need of a reassessment of diagnostic criteria of UV has been suggested5. The value of dermoscopy, a low-cost and rapid skin examination

technique, for clinically discriminating common urticaria and UV has been proposed but in a few small-sized studies10,11. Dermoscopy of CSU typically reveal a red network of linear vessels,

correlating with transient vasodilatation of horizontal subpapillary plexus10,11. In contrast, urticarial lesions of UV characteristically develop dermoscopic irregular/round small purpuric

patches /globules (PG), derived from perivascular haemorrhage associated with inflammatory purpura10,11. We assessed and compare herein for the first time the accuracy of both a clinical and

a clinical-dermoscopic model for discriminating urticarial vasculitis and chronic spontaneous urticaria. The aim of this study was to investigate the value of dermoscopy for the

differential diagnosis of urticariform rashes of CSU and UV, and to evaluate the accuracy of a clinical-dermoscopic diagnostic model versus a clinical approach for discriminating both

diseases. PATIENTS, METHODS AND DEFINITIONS This was a retrospective, chart review, single center study developed from 2003 through 2014 at the department of Dermatology of a tertiary

teaching university hospital (Central University Hospital of Asturias -HUCA-) in northern Spain. The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of Regional Clinical Research of the

Principality of Asturias. All research was performed in accordance with relevant guidelines/regulations and informed consent was obtained from all participants. Inclusion criteria were a

clinical diagnosis of an urticarial rash of at least 6 weeks of evolution (chronic spontaneous urticaria or urticarial vasculitis), complete information regarding clinical and dermoscopic

features gathered during the medical interview and physical examination and a histopathologic confirmatory study. Exclusion criteria were: children, lack of patient´s consent, diagnosis of

other erythematous-purpuric and persistent rashes (erythema multiforme, capillaritis, lymphocytic vasculitis, purpuric pityriasis rosea and insect bites) or absence of complementary data.

Dermoscopic examination preceded biopsy, and both were performed on the same urticariform lesions. Since vasculitis is a dynamic process, and the most characteristic histological features

develop in more recent lesions (neutrophils, haemorrhage, and leukocytoclasia)21, biopsies were taken from lesions less than 24 hours old. The lower leg location was excluded in order to

avoid histological changes caused by venous stasis. Clinical criteria were registered on standardized questionnaires including: duration and persistence (more or less than 24 hours) of

urticariform individual lesions; symptoms (pruritus, pain or burning sensation). Clinical lesions were described as wheals (transient); papules/ plaques (long lasting or undefined); erythema

and purpuric areas were additionally discriminated by diascopy. Clinical variables assessed and selected for subsequent analysis in our study were the classical clinical signs of UV:

persistence (urticariform lesions lasting more than 24 hours as referred by the patients), pain/burning sensation (as it was referred by the patients) and purpura/residual hyperpigmentation.

Results of laboratory examinations were not evaluated given the clinical-dermoscopic nature of the study. Lesions were examined with a 10× manual dermoscope (Delta 10; Heine Optotechnik,

Herrsching, Germany, and later, Dermlite II Pro HR,3Gen Inc, CA, USA). Lesions were photographed with a digital dermoscopic camera (Dermaphot photographic equipment -Heine Optotechnik- and

later Dermlite Foto System). A preliminary study was conducted in order to evaluate whether Delta 10 and Dermlite II Pro HR could give different dermoscopic observations in this setting, but

no differences were found and consequently the dermoscopic observations were considered as a single data set. The dermoscopic procedure was applied taking into account that vessels

recognition is the basis of dermoscopy of urticarial rashes10,11,12,13,14. Because vessels are visualized due to the red blood cells fulfilling and passing through them, dermoscopy was

realized in a two-steps procedure: (a) non-contact dermoscopy (avoiding pressure), allowing recognition of both vascular and purpuric features; (b) dermoscopy applied over diascopy (applying

a glass pressure over the lesion), blanching vessels meanwhile purpuric features persists. Patients who both gave and signed an informed consent to perform a skin biopsy were recruited

throughout the study period from a single outpatient dermatology office. Dermoscopic examination and photographs preceded biopsy. The retrospective scoring of dermoscopic structures,

performed on dermoscopic images by two experienced dermatologists, included the following structures, according to previous studies:10,11,12,13,14 (1) DERMOSCOPIC VASCULAR FEATURES: (a)

Round vessels (correlating with papillary vessels): dotted or globular, according to their size; b) Linear vessels (correlating with horizontal subpapillary vessels): simple, arboriform, and

network structures, with a defined/blurred contour. (2) DERMOSCOPIC PURPURIC FINDINGS: (a) Large homogeneous, structureless purpura (more frequently associated to non-inflammatory forms of

dermal haemorrhage such as traumatic, senile or steroid purpura); b) Irregular/round small purpuric patches/globules (PG): perivascular haemorrhage, related to purpuric inflammatory

processes (pigmented purpuric dermatoses, arthropods reactions, viral and drugs reactions, leukocytoclastic vasculitis, infective organisms). PG are blurred and appear first within a

purpuric and later within an orange-brown background, which may obscure PG if it is prominent or when tissue necrosis appears. (c) Black/purpuric spots (subcorneal and subungual purpura);

(3) OTHER DERMOSCOPIC STRUCTURES: haemorrhagic crusts; erosions/excoriations. In order to obtain a simple and feasible clinical-dermoscopic model for discriminating CSU and UV, and according

to previous studies which include our previous experience10,11,12,13,14, we finally selected and scored only two dermoscopic features: purpuric patches/globules (PG) and red linear vessels.

Histological criteria for diagnosis of UV were: perivascular and interstitial neutrophilic infiltrate; signs of karyorrhexis (nuclear dust); extravasated erythrocytes and deposition of

fibrin in the vessels. Histological criteria for diagnosis of CSU were superficial and deep perivascular and interstitial infiltrate of lymphocytes, neutrophils and eosinophils devoid of

karyorrhexis and vascular fibrin deposition. STATISTICAL ANALYSIS Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software (IBM Corp. Release 2013. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version

21.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp). Univariate and multivariate analyses were conducted by logistic regression. Crude odds ratio (OR), adjusted OR and the corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI)

and p-value were obtained for every clinical and dermoscopic variable. Multivariate analysis was conducted separately for clinical variables and subsequently for both clinical and

dermoscopic variables altogether. Goodness of fit of the multivariate analyses was examined by adjusted R2, likelihood ratio test and correct classification percentage. Specificity,

sensitivity, positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV) were extracted from classification tables for both diagnostic models (the clinical and the

clinical-dermoscopic) according to standard formulas. We considered statistically significant a 2-sided p-value of 0.05. RESULTS In all, 135 patients with urticariform rashes and fulfilling

all inclusion criteria were finally recruited (84 female, 51 male; mean age 50 years; range 20–79 years). Of those, 108 (80%) patients had CSU and 27 (20%) had UV. Descriptive results of

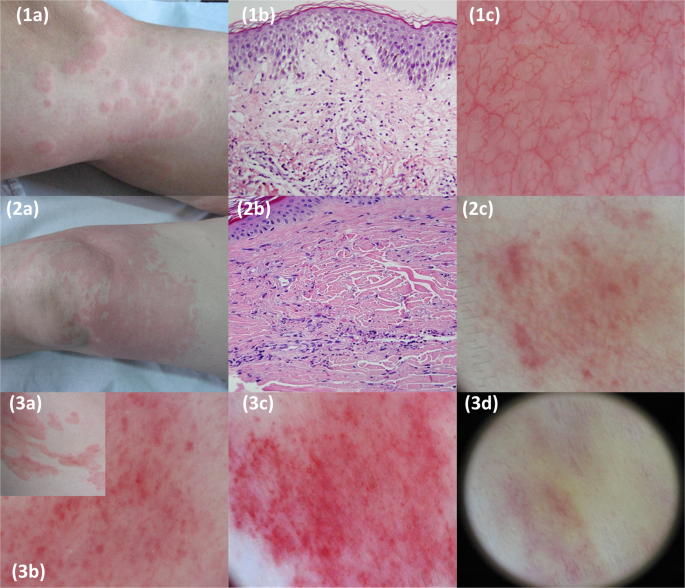

clinical signs, symptoms and dermoscopic features for both histological groups are quoted in Table 1. As regards dermoscopic findings, red linear vessels were observed in the majority of

both CSU and UV patients (85% and 74% respectively) but PG were highly discriminative, being present in most of the patients with UV (n = 19, 70.4%) but only in a minority of patients with

CSU (n = 11; 10.2%) (Fig. 1). Univariate analysis yielded statistical significance for two clinical variables (persistence of lesions, and purpura/residual hyperpigmentation) and one

dermoscopic feature (PG), increasing the likelihood for UV by 7-fold, 9-fold and 21-fold respectively (Table 1). A multivariate regression analysis of a clinical model (where only clinical

variables were entered), maintained the significance for persistence (OR: 4.97; 95% CI 1.85–13.35) and purpura/residual hyperpigmentation (OR 6.34; 95% CI 2.19–18.36) (Table 2). Finally, the

multivariate regression analysis of a clinical-dermoscopic model (based on both clinical and dermoscopic variables), showed that dermoscopic PG were an independent positive predictor for

UV. Only one clinical variable -persistence of lesions- maintained significance. This final model revealed a 19-fold increase in the odds for UV when dermoscopic PG were present and a 6-fold

increase for persistence of lesions, when the diagnosis of UV was compared with CSU (Table 2). Goodness of fit was examined by correct classification percentage (88.9%), adjusted R2 (0.503)

and a significant likelihood ratio test (p < 0.05). Interestingly, it was remarkable that sensitivity was notably higher for the clinical-dermoscopic approach than for the clinical model

(63% vs. 44%) (Table 3). DISCUSSION Dermoscopy is a non-invasive skin magnification technique, which allows a real _in vivo_ subclinical exploration of the skin. Dermoscopy improves and

completes clinical examination by revealing morphologic structures scarcely visible or invisible on the standard naked-eye physical examination, enhancing the most basic of diagnostic

functions in dermatology: the visual inspection15. Dermoscopy has a well demonstrated value in the diagnosis of skin tumours, especially melanoma, but also of many non-tumoral dermatosis,

such as infections and infestations, hair or nail diseases and inflammatory skin conditions15,16,17. In addition, nail fold dermoscopy may be applied for the screening of suspected

connective tissue diseases instead of classic capillaroscopy18. In fact, this valuable low-cost device has even been considered to have in dermatology a role similar to the stethoscope of

general practitioners19. The value of dermoscopy for the differential diagnosis between common urticaria and urticarial vasculitis has been proposed but in small series10,11. In the present

study, we confirm this in a larger series of patients, adding for the first time the evaluation of a clinical-dermoscopic model versus a clinical model for differentiating CSU and UV. It is

our premise that dermoscopic findings should always be interpreted within the overall clinical context of the patient, and integrated with history and standard clinical examination.

Consequently, we developed a clinical-dermoscopic diagnostic model instead of a pure dermoscopic model for differentiating both diseases. Our observations mainly revealed that sensitivity

for differentiating UV from CSU is improved when a clinical-dermoscopic model is applied in comparison with a clinical model (63% vs 44%). The application of a clinical model for

differentiating common urticaria and UV is the gold standard at the present time. The classical clinical signs (urticariform lesions lasting more than 24 hours, pain/ burning sensation,

purpura/residual hyperpigmentation) help to suspect UV, and establish whether a biopsy is needed (to confirm a UV diagnosis) or not (in case of common urticaria). Nevertheless, there are

studies reporting a lack of efficacy of this clinical model, taking into account the variable frequencies of these clinical signs (Table 4)4,5,6,7,8,9. In a study including 47 patients with

biopsy proven UV, Tosoni _et al_. found that most of them did not show the classic clinical features of UV: only 57% of patients referred lesions lasting more than 24 hours and pain was

reported in only 8,6%. Consequently, they suggested the need of a reassessment of the diagnostic criteria of UV5. Additional strategies have included outlining the contour of the lesions for

evaluating the eventual persistence of individual lesions and performing a biopsy according to the response to the treatment with oral antihistamines instead of considering the clinical

features4,5. These methods imply the cons of being time and cost-consuming and invasive, in case of performing routine biopsies. Histopathologically, the essential criteria for the diagnosis

of UV is the presence of karyorrhexis (nuclear dust), joined by extravasated erythrocytes and, at time, by fibrin deposits within walls of vessels6,20,21. Vascular fibrinoid necrosis is

considered rare or absent in UV. Biopsy timing (optimally within the first 24–48 hours) is important to achieve a characteristic picture of UV20,21. Our observations showed that lesions

persistence and purpura/residual hyperpigmentation were the most frequent clinical variables in UV patients, in line with previous investigations (Table 4). Both variables yielded

statistical significance, increasing the likelihood for UV by 7-fold and 9-fold respectively. In contrast, pain/burning sensation was only referred by 26% of patients, and did not reach

significance. Considering only these clinical variables, the global accuracy of the clinical diagnostic model for discriminating UV and CSU was 87%, with 97% specificity for CSU, but with

only a low 44% sensitivity for UV. Interestingly, when dermoscopy was added to the patient evaluation, the clinical-dermoscopic model increased sensitivity to 63%, while maintaining accuracy

(89%), thus outlining the role of dermoscopy in improving the correct non-invasive diagnosis of UV. This improvement was mainly achieved by the detection of subclinical purpuric

patches/globules (PG) that became visible by the use of dermoscopy. Taking into account that the degree of dermal haemorrhage in UV lesions is variable, ranging from evident to unapparent

purpura, identification of dermoscopic PG may be especially useful for those UV lesions with minimal clinical purpuric areas. Indeed, the presence of dermoscopic PG was the most valuable

criteria for discriminating CSU and UV by multivariate analysis (19-fold increase in the odds for UV), while clinical persistence of lesions increased it by 6-fold. Although we did not

investigate this topic, it is also of interest that that PG might be present even in early UV lesions11. Under dermoscopy, the wheals of CU mainly revealed red linear vessels, which

correlate with ectatic, horizontally oriented, subpapillary vessels, and reflect a process of transient vasodilatation of dermal capillaries. They were obscured when prominent oedema was

present (negative areas). Purpuric structures or patches were rare in CSU and must be differentiated from erosions/crusts and from red round vessels (vertical papillary vessels) which appear

as red dots with a clear contour, located along linear vessels, and disappearing after diascopy14. Urticarial lesions of UV also revealed linear vessels but, in contrast to CSU, they

frequently showed blurred irregular/round purpuric structures (PG) within a purpuric (early stage) or orange-brown (late stage) background. Limitations of our study include the retrospective

design and the number of patients evaluated. In conclusion, dermoscopy helps the clinical discrimination between chronic spontaneous urticaria and urticarial vasculitis by improving the

sensitivity of the standard clinical examination (visual inspection). Dermoscopy enhances visualization of subclinical purpuric patches, which are highly indicative of an underlying

vasculitis when confronted with common urticaria. This technique may contribute to optimize decisions regarding biopsy in patients with urticarial rashes, so commonly attended in daily

clinical practice. REFERENCES * Caproni, M. & Verdelli, A. An update on the nomenclature for cutaneous vasculitis. _Curr Opin Rheumatol._ 31, 46–52 (2019). PubMed Google Scholar *

Sunderkötter, C. H. _et al_. Nomenclature of Cutaneous Vasculitis: Dermatologic Addendum to the 2012 Revised International Chapel Hill Consensus Conference Nomenclature of Vasculitides.

_Arthritis Rheumatol._ 70, 171–84 (2018). Article Google Scholar * Jachiet, M. _et al_. French Vasculitis Study Group. The clinical spectrum and therapeutic management of

hypocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis: data from a French nationwide study of fifty-seven patients. _Arthritis Rheumatol._ 67, 527–34 (2015). Article CAS Google Scholar * Dincy, C. V.

_et al_. Clinicopathologic profile of normocomplementemic and hypocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis: a study from South India. _J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol._ 22, 789–94 (2008). Article

CAS Google Scholar * Tosoni, C. _et al_. A reassessment of diagnostic criteria and treatment of idiopathic urticarial vasculitis: a retrospective study of 47 patients. _Clin Exp Dermatol._

34, 166–70 (2009). Article CAS Google Scholar * Mehregan, D. R., Hall, M. J. & Gibson, L. E. Urticarial vasculitis: a histopathologic and clinical review of 72 cases. _J Am Acad

Dermatol._ 26, 441–8 (1992). Article CAS Google Scholar * Kulthanan, K., Cheepsomsong, M. & Jiamton, S. Urticarial vasculitis: etiologies and clinical course. _Asian Pac J Allergy

Immunol._ 27, 95–102 (2009). PubMed Google Scholar * Lee, J. S., Loh, T. H., Seow, S. C. & Tan, S. H. Prolonged urticaria with purpura: the spectrum of clinical and histopathologic

features in a prospective series of 22 patients exhibiting the clinical features of urticarial vasculitis. _J Am Acad Dermatol._ 56, 994–1005 (2007). Article Google Scholar *

Moreno-Suárez, F., Pulpillo-Ruiz, A., Zulueta Dorado, T. & Conejo-Mir Sánchez, J. Urticarial vasculitis: a retrospective study of 15 cases. _Actas Dermosifiliogr._ 104, 579–85 (2013).

Article Google Scholar * Vazquez-Lopez, F., Maldonado-Seral, C., Soler-Sanchez, T., Perez-Oliva, N. & Marghoob, A. A. Surface microscopy for discriminating between common urticaria and

urticarial vasculitis. _Rheumatology (Oxford)._ 42, 1079–82 (2003). Article CAS Google Scholar * Suh, K. S. _et al_. Evolution of urticarial vasculitis: a clinical, dermoscopic and

histopathological study. _J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol._ 28, 674–5 (2014). Article CAS Google Scholar * Vazquez-Lopez, F., Garcia-Garcia, B., Sanchez-Martin, J. & Argenziano, G.

Dermoscopic patterns of purpuric lesions. _Arch Dermatol._ 146, 938 (2010). Article Google Scholar * Vazquez-Lopez, F., Kreusch, J. & Marghoob, A. A. Dermoscopic semiology: further

insights into vascular features by screening a large spectrum of nontumoral skin lesions. _Br J Dermatol._ 150, 226–31 (2004). Article CAS Google Scholar * Vazquez-Lopez, F.,

Valdes-Pineda, F. Inflammatory diseases: common urticaria and urticarial vasculitis. In: Micali G, Lacarruba F, ed. _Dermatoscopy in clinical practice: beyond pigmented lesions_, second

edition. Boca Raton: Taylor & Francis. 87–91 (2016). * Lallas, A. _et al_. Dermoscopy in general dermatology: practical tips for the clinician. _Br J Dermatol._ 170, 514–26 (2014).

Article CAS Google Scholar * Dinnes, J. _et al_. Visual inspection and dermoscopy, alone or in combination, for diagnosing keratinocyte skin cancers in adults. _Cochrane Database Syst

Rev._ 12, CD011901 (2018). PubMed Google Scholar * Dinnes, J. _et al_. Dermoscopy, with and without visual inspection, for diagnosing melanoma in adults. _Cochrane Database Syst Rev._ 12,

CD011902 (2018). PubMed Google Scholar * Fueyo-Casado, A., Campos-Muñoz, L., Pedraz-Muñoz, J., Conde-Taboada, A. & López-Bran, E. Nail fold dermoscopy as screening in suspected

connective tissue diseases. _Lupus._ 25, 110–1 (2016). Article CAS Google Scholar * Lallas, A. & Argenziano, G. Dermatoscope-the dermatologist’s stethoscope. _Indian J Dermatol

Venereol Leprol._ 80, 493–4 (2014). Article Google Scholar * Ackerman, A.B. _Histologic diagnosis of inflammatory skin diseases_. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins, 1997. * Peteiro, C. &

Toribio, J. Incidence of leukocytoclastic vasculitis in chronic idiopathic urticaria. Study of 100 cases. _Am J Dermatopathol._ 11, 528–33 (1989). Article CAS Google Scholar Download

references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Statistical analysis and interpretation were completed with the assistance of the Scientific and Technical Services (statistical consultancy unit) from the

University of Oviedo. AUTHOR INFORMATION AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Department of Dermatology, Central University Hospital of Asturias, Oviedo, Spain B. García-García, J. Aubán-Pariente, P.

Munguía-Calzada & F. Vázquez-López * Department of Pathology, Central University Hospital of Asturias, Oviedo, Spain B. Vivanco * Dermatology Unit, University of Campania, Naples, Italy

G. Argenziano Authors * B. García-García View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * J. Aubán-Pariente View author publications You can also search

for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * P. Munguía-Calzada View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * B. Vivanco View author publications You

can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * G. Argenziano View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * F. Vázquez-López View author

publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CONTRIBUTIONS B.G.G., G.A. and F.V.L. wrote the main manuscript text. J.A.P., P.M.C. and B.V. prepared figures and

tables. All authors reviewed the manuscript. CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to B. García-García. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS The authors declare no competing interests.

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION PUBLISHER’S NOTE Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS OPEN

ACCESS This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format,

as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third

party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the

article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright

holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE García-García, B., Aubán-Pariente,

J., Munguía-Calzada, P. _et al._ Development of a clinical-dermoscopic model for the diagnosis of urticarial vasculitis. _Sci Rep_ 10, 6092 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-63146-w

Download citation * Received: 17 November 2019 * Accepted: 16 March 2020 * Published: 08 April 2020 * DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-63146-w SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the

following link with will be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer

Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative