Play all audios:

ABSTRACT Prenatal alcohol exposure (PAE) causes permanent cognitive disability. The enteric microbiome generates microbial-dependent products (MDPs) that may contribute to disorders

including autism, depression, and anxiety; it is unknown whether similar alterations occur in PAE. Using a mouse PAE model, we performed untargeted metabolome analyses upon the

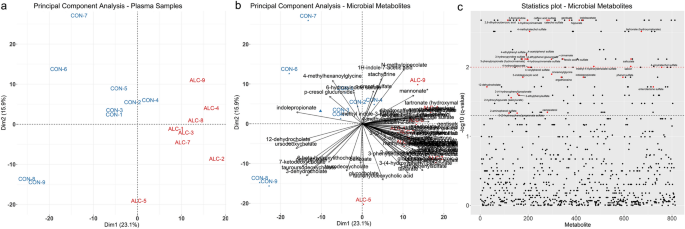

maternal–fetal dyad at gestational day 17.5. Hierarchical clustering by principal component analysis and Pearson’s correlation of maternal plasma (813 metabolites) both identified MDPs as

significant predictors for PAE. The majority were phenolic acids enriched in PAE. Correlational network analyses revealed that alcohol altered plasma MDP-metabolite relationships, and

alcohol-exposed maternal plasma was characterized by a subnetwork dominated by phenolic acids. Twenty-nine MDPs were detected in fetal liver and sixteen in fetal brain, where their impact is

unknown. Several of these, including 4-ethylphenylsulfate, oxindole, indolepropionate, p-cresol sulfate, catechol sulfate, and salicylate, are implicated in other neurological disorders. We

conclude that MDPs constitute a characteristic biosignature that distinguishes PAE. These MDPs are abundant in human plasma, where they influence physiology and disease. Their altered

abundance here may reflect alcohol’s known effects on microbiota composition and gut permeability. We propose that the maternal microbiome and its MDPs are a previously unrecognized

influence upon the pathologies that typify PAE. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS ALCOHOL CONSUMPTION DURING PREGNANCY DIFFERENTIALLY AFFECTS THE FECAL MICROBIOTA OF DAMS AND OFFSPRING

Article Open access 12 July 2024 INFANT CIRCULATING MICRORNAS AS BIOMARKERS OF EFFECT IN FETAL ALCOHOL SPECTRUM DISORDERS Article Open access 14 January 2021 METABOLOMIC ANALYSIS OF MATERNAL

MID-GESTATION PLASMA AND CORD BLOOD IN AUTISM SPECTRUM DISORDERS Article 10 April 2023 INTRODUCTION Prenatal alcohol exposure (PAE) causes behavioral, growth, and physical anomalies known

as Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD); the deficits in cognition, learning, memory, and executive function persist across the lifespan1,2,3. FASD is a significant public health problem.

In the US, an estimated 4.1% (range 3.1–5.0%) of U.S. first graders meet the criteria for an FASD diagnosis4, and 3.9% of pregnant women admit to binge drinking in the past 30 days (four or

more drinks per occasion)5. Unbiased sampling of newborn bloodspots reports even higher exposure rates, and 8.4% in a Texas-statewide sample tested positive for PAE during the month prior to

birth6. Despite these high rates of prevalence, implementation of screening to identify alcohol-exposed pregnancies remains challenging for complex reasons. Social stigmas surrounding

gestational alcohol consumption discourage accurate self-disclosure7. Biomarkers such as ethyl-glucuronide and phosphatidylethanol have diagnostic utility8,9, but their interpretation is

complicated by modifying factors that include the level, pattern, and timing of drinking, genetics, nutritional status, and maternal body mass index10,11,12,13. A clearer understanding of

alcohol-related biomarkers would inform their development and interpretation, and could be leveraged into interventions that attenuate alcohol’s damage. One candidate modifier of FASD that

receives little attention is the microbiome. The enteric microbiome modulates host activity, in part, through its generation of small molecules; these microbial-dependent products (MDPs)

include direct products of microbial metabolism (volatile fatty acids, indoles), microbial action upon host-derived metabolites (secondary bile acids), and compounds liberated from the food

matrix by microbial digestion (phytochemicals). These are absorbed predominantly through the colon and circulate at physiologically relevant concentrations (nanomolar to high micromolar),

where they act as high-affinity ligands for signaling systems that govern diverse processes including bile acid synthesis, gut function, insulin sensitivity, immune function, and vascular

health14,15,16,17,18. Relevant for FASD, dysfunction of the enteric microbiome has been implicated in neurological disorders including Alzheimer’s disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis,

autism spectrum disorder, depression, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, and seizure risk14,19,20,21,22,23,24. Various MDPs have been shown to interact with the nervous system at

physiologically relevant concentrations. For example, microbial-derived indoles cross the blood–brain barrier to modulate motor, anxiety, and other behaviors, as well as microglial-mediated

neuroinflammation25,26,27,28. The microbial-derived polyphenol 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetate modulates dopamine and catecholamine metabolism and clearance24,28,29. Mechanistically, fecal

transfers from diseased mice can recreate the MDP signatures, pathologies, and select characteristics of neurological disorders including autism, depression, Parkinson’s disease, amyotrophic

lateral sclerosis, and ketogenic refractory epilepsy19,21,23,30,31,32. Although microbial dysfunction is causative in alcohol-related diseases such as cirrhosis and pancreatitis, potential

contributions to FASD are unknown. Alcohol reduces the immunological activities and mucosal tight junctions that maintain the intestinal barrier’s integrity, and thus enhances paracellular

entry of MDPs into the circulation33,34. Alcohol also alters the enteric microbiome composition and promotes the growth of gram-negative facultative anaerobes that produce exotoxins such as

lipopolysaccharide35,36,37,38. These signal through the toll-like receptors (TLR) to stimulate the inflammation, fibrosis, and cell death that underlie alcoholic end-organ damage. Microbiome

contributions to FASD were indirectly suggested by recent demonstrations that loss-of-function in TLR4, which mediates inflammatory responses to microbial LPS, attenuates neuroinflammatory

responses to improve memory, anxiety and social behaviors in mouse models of PAE39,40. However, it is unknown whether PAE alters the maternal enteric microbiome and the spectrum of

biochemicals that it generates, whether these reach the fetus, and how such changes contribute to the pathologies of FASD. To gain insight into this question, we employed an untargeted

UPLC–MS/MS approach and characterized the MDP profile of mother and fetus, using our established mouse model of PAE41. We report here that MDPs comprise a distinctive and significant

biosignature that distinguishes alcohol-exposed dams from their controls. We readily detect MDPs within the fetus, where PAE again alters their abundance. Several of these analytes were

previously implicated in neurological dysfunction. Data implicate MDPs as a hitherto unappreciated contributor to FASD. RESULTS LITTER CHARACTERISTICS The alcohol dose used (3 g/kg) caused a

mean blood alcohol concentration of 211 ± 14 mg/dl at 30 min post-gavage, and the mice were inebriated but did not pass out. Alcohol exposure (ALC) did not affect maternal food intake41 or

overall weight gain (Supplementary Table S1 online); the ALC dams had a non-significant trend to reduced weight gain during the alcohol exposure period (embryonic day (E) 8.5–E17.5) compared

to controls (CON, 11.22 ± 0.47 g; ALC, 9.98 ± 0.44 g; _p_ < 0.07). Prenatal alcohol exposure did not affect litter size (_p_ = 0.31) or fetal survival (_p_ = 0.69) at E17.5, and no

adverse outcomes were observed in dam or fetus. ALCOHOL-EXPOSED MATERNAL PLASMA IS ENRICHED IN MDPS Untargeted metabolite analysis identified 813 biochemicals in maternal plasma, 733 with

known chemical structures and 80 that were unknown. Of the 813 metabolites, 146 had significantly altered representation (q < 0.05 by Mann–Whitney U-test followed by Benjamini–Hochberg

correction) in response to PAE. Principle Component Analysis (PCA) of the metabolite profiles showed that alcohol-exposure is a clear driver of variance within the metabolic profiles, and

placed one dam (ALC-6) as an outlier (Supplementary Figure S1A,B online). This dam’s plasma ethyl glucuronide level was just 14.0% of that for the other alcohol-exposed dams, suggesting a

gavage error, and she was removed from further analysis. Repeating the PCA with omission of ALC-6 revealed that the metabolomic profile explained the separation of the samples by

intervention. PC1 explained 23.1% of the sample variance, and PC2 explained an additional 15.9% (Fig. 1a), and visual inspection of the data set revealed that MDPs were among the strongest

drivers of PC1 and PC2 (Fig. 1b). Analysis of the log-fold change _q_-values using T-statistic similarly found that MDPs were over-represented (Fig. 1c), and of 146 metabolites having a _q_

≤ 0.05, 28.1% (N = 41) were MDPs, although they comprised 10.5% of the 733 known metabolites. Housing assignment can also affect enteric microbiome composition42; remapping the PCA results

against housing assignment affirmed that cage assignment did not influence analyte distribution or abundance (Supplemental Fig. S1C). Of the 70 MDPs detected within control and ALC maternal

plasma, 41 (58.6%) had significantly altered representation (_q_ ≤ 0.05) in response to alcohol (Table 1); the preponderance (44) were enriched by alcohol-exposure and only two were

significantly reduced. The majority of the MDPs (36/70) were plant phenolics that originated from the microbial-mediated fermentation of ingested lignins in the cage bedding18, and

potentially from starch- or cellulose-bound flavonoids in the purified diet43. Alcohol exposure significantly enriched the abundance of 29 plant-derived phenolics, including the alcoholic

β-glucoside salicin (12.98-fold), catechol sulfate (7.41-fold), cinnamate (5.28-fold), ferulic acid 4-sulfate (4.50-fold), hippurate (3.37-fold), caffeic acid sulfate (3.21-fold), phenyl

sulfate (3.20-fold), and salicylate (3.11-fold). None had reduced abundance, and the overall pattern was one in which ALC significantly increased the plasma abundance of plant-derived

aromatics and their phase-II metabolites. Alcohol-exposure also increased the maternal plasma levels of multiple indole derivatives including indoleacetate, indolelactate, indolin-2-one,

3-formylindole, and 3-indoleglyoxylic acid (range 1.47–1.76-fold), and decreased the abundance of indolepropionate (0.41-fold). It also altered the abundance of secondary bile acids, which

are generated by microbial action upon those primary bile acids not resorbed in the ileum. Of the eleven secondary bile acids detected in maternal plasma, eight were less abundant in ALC

dams, although only 12-dehydrocholate was significantly reduced (0.02-fold, q = 0.0193). In contrast, taurohyodeoxycholic acid (2.21-fold) and ursocholate (2.19-fold) were elevated in

alcohol-exposed maternal plasma, but not significantly. Also increased were the sugar derivatives ribitol, tartronate, and threonate, and the betaine ergothioneine. Although not

microbial-derived, the phytosterols beta-sitosterol and campesterol were also elevated by alcohol-exposure. MDPS COMPRISE A SIGNIFICANT BIOSIGNATURE IN PLASMA OF ALC DAMS We utilized

Hierarchical Clustering of Principal Components (HCPC) to understand the relationships among these metabolite features. This placed the 813 metabolites into five, evenly distributed clusters

using Ward’s method. The MDPs were unevenly distributed across the clusters, and a majority segregated into cluster 1 (57.8%, 41 of 71 MDPs), followed by clusters 3 (11/71) and 5 (11/71)

(Fig. 2a). Clusters 2 and 4 were dominated by endogenous metabolites. This clustering of MDPs primarily reflected their contribution to PC1, which captured the greatest class separation

between ALC and control (Fig. 2b). The MDPs in Cluster 1 were predominantly plant-derived aromatics, and all were enriched in ALC (Table 2; Supplementary Table S2 online). In contrast, the

MDPs in cluster 5 were enriched in control plasma and they were mostly (9/11) secondary bile acids. Clusters 3 and 4 were highly skewed towards other Principal Component Dimensions, and

repeating the PCA and PLSDA analysis according to PC2 (Supplementary Figure S2 online) suggested that dimension 2 modeled the time of plasma collection following the intervention. This

cluster separation was relevant only for the ALC dataset and not the controls. Because this influence did not involve the MDPs, it is the focus of a separate investigation described

elsewhere. In summary, the HCPC and PLSDA analysis revealed that the MDPs clustered by treatment response based on the PC loadings. These MDPs had a disproportionate influence in explaining

exposure variance within the metabolite dataset, and their influence was defined by their molecular structure, in addition to their relative abundance and p-value. Correlation analysis

further informs whether influences in addition to exposure drive the metabolite relationships and variance across the dataset. We repeated the hierarchical clustering using Spearman’s

correlation (Fig. 2c). The strong association between the plant phenolics was retained, and 47/71 were correlated within Cluster 5, comprising 27.8% of that cluster, and these were all

enriched by alcohol exposure (Table 3, Supplementary Table S3). New associations also emerged, and Cluster 1 (13/71) included a mixture of phenolics, indoles, and secondary bile acids

largely unaffected by alcohol-exposure. These findings further support that alcohol exposure strongly influenced plasma MDP content, and their relationships further depended on chemical

structure and metabolic fate. Metabolite classes that tightly cluster together in the correlation analysis share a consistent response to treatment. Similarly, metabolites that are

downstream products of a shared cellular process affected by alcohol also will maintain equilibrium with each other during the analysis. Thus, highly conserved correlations likely represent

a metabolite set that exists within a molecular equilibrium. The consistent clustering of MDPs in both the HCPC and Spearman’s correlation suggested the existence of such relationships. To

investigate this, we filtered the correlation matrix to correlations greater than 0.9, and subjected these to network correlation analysis, and segregated by treatment. This yielded very

different network structures for Control and ALC maternal plasma (Fig. 3). The network architecture of the controls was comprised of two dense hubs connected by tightly-linked interactions,

and each joined to separate satellites that were in turn weakly linked (Fig. 3a). In contrast, the ALC plasma network architecture was dominated by just a single dense hub that was more

loosely connected with a second, more diffuse hub, each with an adjoining smaller satellite (Fig. 3b). The MDPs held quite different relationships within these two architectural structures,

and the plant phenols formed a dense mini-structure in ALC, whereas no such network appeared in controls; the latter’s largest MDP set was a mix of phenolics, indoles, and sugar acids. A

parallel analysis that focused on Spearman correlations less than 0.9 revealed similarly divergent networks, such that the Control network (Fig. 3c) featured far fewer metabolites than did

ALC (Fig. 3d), signaling that the plasma metabolite profile of ALC was characterized by a loss of tight regulatory control. This is endorsed by the more dispersed structure of the ALC

network and suggests an overall weakening of metabolite relationships that may be a product of dysregulated metabolism. Overall, the analyses revealed that alcohol-exposure altered the

relationships between MDPs and endogenous metabolites, and endorsed the MDP biosignature for alcohol-exposed maternal plasma. Additional insight was obtained by merging the Control and

Alcohol plasma datasets, and again performing network analysis filtered by the Spearman’s correlations. For the negative correlations, this only yielded two-node subnetworks, none of which

contained MDPs. For the positively correlated metabolites, this yielded a network dominated by MDPs enriched in ALC (Fig. 4). This included a tightly correlated subnetwork of nineteen plant

phenolics (hippurates, catechols, salicins, phenols) and a smaller, linked subnetwork of sugar acids that was further linked with endogenous-derived sugar acids. Also included were several

unknowns including one tentatively identified as the plant-derived phenolic pyrocatechol sulfate (X-17010), based on its fragmentation mass. The tight relationship between these phenolic

MDPs suggested they were at equilibrium with each other in response to alcohol, and further suggested that that their enrichment shared a similar or conserved molecular process or cause.

MDPS ARE ENRICHED IN THE PAE FETUS We asked if this ALC-dependent MDP biosignature extended to other maternal–fetal compartments. Five additional MDPs were detected in these tissues

(kojibiose, beta-guanidinopropanoate, hyodeoxycholate, taurohyocholate, and taurolithocholate), for a total of 75 MDPs. Many of the plasma MDPs were phase-II conjugates, synthesized

primarily by enterocytes and hepatocytes to facilitate their urinary (sulfate and glucuronide) or biliary (O-methyl) excretion. However, the MDP profile of maternal liver (32/75)

significantly differed from that of plasma (Table 4) and was dominated by secondary bile acids and sugar derivatives; far fewer plant phenolics were detected (10 vs. 36). Fold-changes in

response to alcohol were modest, and just 10 of 32 (31.2%) hepatic MDPs had significantly altered representation in ALC. Analysis in the T-statistic (Fig. 5a) affirmed their lower

representation among the significantly altered biofeatures in maternal liver (10/205), suggesting that MDPs were not major drivers of metabolite variance in response to alcohol for this

tissue. Many metabolites within maternal plasma exchange readily across the placenta and become bioavailable to the fetus. Thirty-one MDPs were detected in placenta, including plant

phenolics, indoles, and secondary bile acids (Table 4). Of these, alcohol significantly altered the abundance of 11 MDPs, and seven plant-derived phenolics and several betaines were

enriched, while indolepropionate and gluconate were reduced. The placental data suggested that MDPs might circulate within the fetus. Although fetal plasma was too scant for analysis, other

fetal tissues were readily characterized (Table 4). Thirty MDPs were detected in fetal liver and/or brain. The fetal liver profile largely replicated that of maternal liver, and all but five

(enterolactone sulfate and four secondary bile acids) of the 32 metabolites present in maternal liver were also detected in fetal liver. Responses to alcohol also trended similarly, with

enrichments in hippurate (2.43-fold), catechol sulfate (1.83-fold), salicylate (1.46-fold), phenol sulfate (1.34-fold), and ergothioneine (1.29-fold). Although not MDPs, the phytosterols

beta-sitosterol (1.76-fold) and campesterol (1.31-fold) were also elevated. Sixteen MDPs were detected in fetal brain (Table 4). These included plant phenolics (benzoate, hippurate, p-cresol

sulfate, phenol sulfate, 4-vinylcatechol sulfate), indoles (indolelactate, indolepropionate, 3-formylindole), sugar derivatives (mannonate, gluconate, erythritol, tartronate),

ergothioneine, and campesterol. Alcohol altered the abundance of several MDPs, and it elevated hippurate (1.82-fold), phenol sulfate (2.72-fold), and ergothioneine (1.36-fold), and reduced

p-cresol sulfate (0.81-fold) and gluconate (0.73-fold). In contrast to maternal plasma, MDPs did not explain exposure-related variance in the T-statistic (Fig. 5b,c,d), and they comprised

few of the metabolites having significantly altered representation in placenta (11/116), fetal liver (2/29), and fetal brain (1/54). DISCUSSION The enteric microbiome generates a complex

spectrum of biochemicals that have a substantial influence on the host14,15,16,17. This is the first study to document that PAE significantly alters this biochemical profile within the

maternal–fetal dyad. This metabolite profile is derived from and influenced by the composition of the enteric microbiota, and the changes documented here are consistent with alcohol’s known

ability to alter that composition36,37. Growing evidence demonstrates that microbe-derived products are mechanistic in the pathologies that underlie alcohol-related organ damage33,34,35, and

our findings suggest that parallel mechanisms may operate during PAE with similar pathological consequences. Importantly, we show that these biochemicals cross the placenta and circulate

within the fetus, where they could directly impact development. Indeed, many of these biochemicals having significantly altered representation, mostly plant-derived phenolics and secondary

bile acids, have well-documented effects upon host physiological and cellular processes16,18,44,45. Our demonstration that alcohol alters their abundance within both mother and fetus

introduces a novel mechanism by which PAE could alter fetal development, and thus these findings have clinical relevance. Moreover, these biochemicals form a plasma biosignature that

distinguishes the PAE pregnancies. There is substantial interest in identifying biomarkers of alcohol exposure as these enable clinicians to focus interventions on those pregnancies at

greatest risk. In addition to the established markers phosphatidylethanol and ethyl-glucuronide8,9, recent studies have identified microRNA46 and cytokine-chemokine47 plasma signatures that

may be selective for alcohol-exposed pregnancies. An MDP signature could complement those measures, as some features were enriched seven- to 13-fold in this model. Although the composition

of any microbial biosignature is shaped by considerations including diet, the enteric community’s taxonomic structure, exome profile, and host species and sex15,48,49, our data lend

proof-of-concept for the existence of such a biosignature that may complement existing markers and further enhance their specificity to detect PAE. How might these microbial metabolites

impact fetal development and alcohol-related pathologies? In this study, the dominant microbial compounds enriched by alcohol were plant-derived aromatics, mostly phenolic acids that

originate from the fermentation of ingested lignin bedding and starch-bound flavonoids18,43,50. These same phytochemicals are abundant in edible plants, and the human enterocyte and

microbiota have similar capabilities to release, convert, and absorb these compounds18. Humans consume an estimated two-plus grams daily of plant phytochemicals from foods and beverages, and

plasma levels typically range in the nanomolar to low micromolar range51,52. This is the first report that these compounds circulate within the fetus. These compounds have a short half-life

due to their rapid excretion44; that alcohol enriched both their aglycone and conjugated forms suggests that it enhanced and/or prolonged their enteric metabolism and intestinal absorption,

as well as their phase II conversion. In human studies, these compounds are typically associated with improved health outcomes and reduced all-cause mortality. Mechanistically, phenolic

acids improve vascular tone through stimulation of endothelial Nrf2 and nitric oxide signaling, and have anti-inflammatory actions through their inhibition of pro-oxidant enzyme-signaling

cascades18,44; thus, their elevation in PAE may potentially mitigate some of alcohol’s damage to the mother-fetal dyad. They also act as prebiotics and directly alter the microbiome

composition52. Highly processed Western-style diets are low in lignins and flavonoids, and their enrichment here represent a novel means by which diet may modulate FASD outcome. The

microbiota-derived secondary bile acids also defined the ALC dams, but were negative drivers within the Principal Components and Pearson Correlation analyses. Along with their parent primary

bile acids, they comprised a correlated network that suggests a shared mechanistic response to PAE. Bile acids and the enteric microbiota operate in a two-way interaction that governs both

bile acid metabolism and microbiota composition45,53. Our data suggest that alcohol altered that regulatory relationship, and this is consistent with its known effects on host-microbial bile

acid pools, wherein chronic alcohol abuse elevates secondary bile acid levels54,55, perhaps through dysregulation of hepatic bile acid synthesis56. The reductions here may reflect our

shorter exposure (days vs. months) and perhaps influences from the pregnancy state57. We could not infer which microbial populations mediated these reductions because secondary bile acid

metabolism is redundant across phyla45. The elevated taurine conjugates in the alcohol-exposed maternal liver implicate reduced microbial deconjugation and/or hepatic amidation as additional

modifying mechanisms. Secondary bile acids modulate numerous processes. They stimulate the production of antimicrobial peptides that suppress the growth of proinflammatory, gram-negative

microbes58,59, and their reductions here suggest a means by which alcohol promotes the proinflammatory environment that worsens fetal development47,60. Bile acid interactions with their RXR,

FXR, LXRα, and GPBAR1 receptors affect insulin sensitivity, adiposity, and lipid metabolism, conditions that independently worsen gestational outcomes61. Secondary bile acids were recently

detected in the porcine fetus62, suggesting their fetal presence is not unique to rodents; however, any biological impact upon fetal development is currently unknown. Taken together, these

data suggest that alcohol disturbs microbiota—bile acid interactions in a manner that could negatively impact maternal–fetal health. Additional MDPs altered by PAE included indoles and

betaine derivatives. The betaine-like compounds ergothionine and hercyine scavenge free radicals and reduce oxidative damage63, and their elevation in PAE may confer some protection. Indoles

are generated by microbial tryptophanase and can influence brain and behavior. Oxindole, which was elevated in plasma from ALC dams, promotes anxiety-like behaviors in the open field and

elevated plus-maze tests in rats26, behaviors also seen in PAE. Conversely, indolepropionate confers protection against neuroinflammation and TLR4 signaling through interactions with the

microglial arylhydrocarbon receptor22,28, and sustains gut integrity through the pregnane X receptor (PXR)64; its sharp reduction in ALC plasma and placenta is consistent with alcohol’s

pro-inflammatory actions38,60. Indoles also compete with amino acid and neurotransmitter efflux at the blood–brain barrier, and are functionally linked with anxiety, depression, cognitive

impairment, and Parkinson’s disease20,26,65,66. As physiologically relevant agonists for the arylhydrocarbon receptor, they modulate not only immune function but also xenobiotic responses

and insulin sensitivity67. We detected at least four indoles in fetal brain (indoleacetate, indolelactate, indolepropionate, 3-formylindole), and because many indole derivatives have yet to

be characterized functionally, their impact upon neurodevelopment merits additional investigation. This study has several important limitations. The first is that not all MDPs could be

investigated. Many remain unannotated and likely comprise some of the unknown metabolites detected here. We also did not analyze the gut microbiota, and thus do not know if and how alcohol

affects its composition in pregnancy. This study was not designed to distinguish those metabolites having a dual microbial-host origin, such as lipids, organic acids, and polyamines, nor

does the methodology detect the larger MDPs that contribute to alcohol’s proinflammatory actions, such as LPS33,38,64. Finally, we cannot distinguish the relative contributions of enteric

synthesis and cecal permeability to the elevated MDP abundance. As alcohol promotes both dysbiosis and gut permeability33,34,35,36,37,38, both mechanisms likely contribute; additional

studies will inform this question. In summary, alcohol alters the maternal plasma MDP profile, and by inference perhaps the microbiota composition that produced them. Several of the MDPs

elevated by PAE (catechol sulfate, 4-ethylphenylsulfate, erythritol, indolepropionate, oxindole, p-cresol, salicylate) have been implicated in neuroinflammation, depression, anxiety, and

autism22,26,28,30,65,66, outcomes also characteristic for PAE1,2. Other compounds may confer benefits through effects on vascular tone and anti-inflammatory actions, and thus could mitigate

some of alcohol’s damage to the fetus. These MDPs circulate within the fetus, where their impact is unknown. Their enrichment, particularly in phenolic acids, constitutes a characteristic

biosignature that distinguishes the PAE pregnancies, and their enrichment might also signal the presence of proinflammatory MDPs such as LPS. Together, these data suggest the novel

hypothesis that the maternal microbiome may be an important mechanistic driver in the pathologies that underlie FASD. METHODS ANIMAL HUSBANDRY AND ALCOHOL-EXPOSURE Five-week-old C57BL/6 J

female mice (Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME) were housed as pairs or trios in ventilated cages on aspen chip bedding (Northeastern Products Corp, Warrensburg NY) and cotton nesting

material (Nestlets, Ancare, Bellmore NY), and a 12 h light/dark cycle (lights on 7am). Mice consumed the fixed-nutrient, purified diet AIN-93G (TD.94045, Envigo-Teklad, Madison WI68)

throughout the study; its composition is provided in Supplementary Table S4 online. At age 8 weeks, mice were mated overnight to C57BL/6 J males. The morning of vaginal plug detection was

defined as E0.5. On E8.5, pregnant females received either 3 g/kg alcohol (ALC; USP grade) or isocaloric maltodextrin (control; LoDex-10; #160175, Envigo-Teklad) once daily (9am) through

E17.5 via oral gavage. Experimental group was assigned on E8.5 using a random number generator (Excel), and mice were cohoused by treatment with those sharing the same plug date. Four hours

after the gavage on E17.5, mice were killed by isoflurane overdose and their tissues were flash-frozen for analysis. Blood alcohol concentrations were quantified using oxometry (Analox GM7;

London, UK), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Studies were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the David H. Murdoch Research Institute, and were performed in accordance

with relevant guidelines and regulations. EXPERIMENTAL BLOCKING We evaluated maternal plasma, maternal liver, placenta (with decidua removed), fetal liver, and fetal brain, from 9 Control

and 9 ALC dams and their litters. To obtain sufficient fetal tissue for analysis, it was necessary to pool the fetuses. Specifically, for each litter, we held uterine position constant and

defined Fetus 1 as occupying the position closest to the right ovary. Fetuses were numbered consecutively thereafter. Selecting fetuses 1 through 4, we combined half of fetal livers 1

through 4, and half of fetal brains 1 through 4, and submitted each pooled sample for metabolome analysis. Thus, each dam is an individual biological sample, and each fetal sample is the

pool from Fetus 1, 2, 3, and 4. Each placental sample was derived from half of placental 1 and 2, because this tissue was larger. For each group (ALC, Control), we subjected nine individual

dams and nine fetal pools to metabolome analysis. METABOLITE ANALYSIS Untargeted metabolite analysis was performed by Metabolon (Morrisville, NC), and their detailed methods are presented in

Supplemental Methods S1. To summarize, samples were treated with methanol to remove protein, and then divided into five aliquots for reverse phase (RP)/UPLC–MS/MS with positive ion mode

electrospray ionization (ESI, 2 samples), RP/UPLC–MS/MS with negative ion mode ESI (one sample), and HILIC/UPLC–MS/MS with negative ion mode ESI (one sample); a fifth sample was reserved for

back-up. Quality controls include technical replicates of pooled experimental samples, extracted water and solvent blanks, addition of recovery standards to monitor variability and

efficiency, and internal standards that assessed instrument variability and aided chromatographic alignment. Sampling order was randomized across each platform run. Compounds were identified

by comparison to library entries of purified standards or recurrent unknown entities. Identification was based on the criteria of retention time/index, match to a mass to charge ratio ± 10

ppm, and chromatographic data (MS/MS spectrum). Proprietary visualization and interpretation software were used to confirm peak identities. Peaks were quantified using area-under-the-curve.

STATISTICAL ANALYSES OF METABOLITES In the initial analysis, we tested for unequal variance between the Control and ALC groups using Shapiro-Wilks test, and tested for normality using the

Levine’s test, followed by analysis for significance using the Mann–Whitney U-test. For values that were missing, we imputed the minimum value obtained for that metabolite in that tissue,

and Supplemental Table S5 presents the raw LC–MS/MS dataset, as provided by Metabolon. _P_-values were adjusted for multiple testing correction using the Benjamini–Hochberg False Discovery

Rate (FDR) correction69, and are presented as _q_-values. Analyses were performed in ArrayStudio on log transformed data70. For analyses that were not standard within ArrayStudio, the

program R (version 3.6.1)71) was used. Fold-change was determined as the difference between group averages, placing ALC in the numerator, and is reported in log2 values. For the discriminant

analysis between ALC and Controls, the plasma data were scaled to a zero mean with a standard deviation of one for each metabolite, and were then run through multivariate analysis.

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was performed using FactoMineR (version 2.3)72 to test for separation between the treatment and control groups, and to identify outliers and question

trends that supported class separation of the experimental design; findings were visualized using Factoextra R (version 1.0.7)73. Metabolite-metabolite correlation analysis was calculated

using Spearman’s correlation on un-scaled data, and were analyzed and visualized in ggplot2 (version 3.3.0)74 using hierarchical clustering for comparison with Hierarchical Clustering of

Principal Components (HCPC). The metabolite-metabolite correlation matrix was used to construct a network visualization to explore similarly affected metabolites. The correlation networks

were constructed in Cytoscape (version 3.7.2)75 using the RCy3 package (version 2.6.3)76 and aMatReader (version 1.1.3)77. Only Spearman’s correlations above 0.9 were included in the

network, and nodes were overlaid with descriptive statistics including q-value and log-fold change (logFC). To evaluate metabolites acting in concert, we explored the loadings plot of the

sample PCA again using FactoMineR on transposed scaled data and visualized in factoextra. Hierarchical clustering analysis was used to cluster the regression factor scores of the loadings

identified in the PCA using Ward’s minimum variance method and squared Euclidean distance in FactoMineR. This analysis, including the final k-means clustering, was identically applied to the

correlation matrix and visualized in ggplot. REFERENCES * Hoyme, H. E. _et al._ Updated clinical guidelines for diagnosing Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders. _Pediatrics_. 138, e20154256.

https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-4256 (2016). * Kable, J. A. _et al._ Neurobehavioral disorder associated with prenatal alcohol exposure (ND-PAE): Proposed DSM-5 diagnosis. _Child

Psychiatry Hum. Dev._ 47, 335–346 (2016). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Marquardt, K. & Brigman, J. L. The impact of prenatal alcohol exposure on social, cognitive and affective

behavioral domains: Insights from rodent models. _Alcohol._ 51, 1–15 (2016). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * May, P. A. _et al._ Prevalence of fetal alcohol spectrum

disorders in 4 US communities. _JAMA_ 319, 474–482 (2018). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Denny, C. H., Acero, C. S., Naimi, T. S. & Kim, S. Y. Consumption of alcohol

beverages and binge drinking among pregnant women aged 18–44 years - United States, 2015–2017. _MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep._ 68, 365–368 (2019). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google

Scholar * Bakhireva, L. N. _et al._ Prevalence of prenatal alcohol exposure in the State of Texas as assessed by phosphatidylethanol in newborn dried blood spot specimens. _Alcohol. Clin.

Exp. Res._ 41, 1004–1011 (2017). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Earnhart, C. B., Morrow-Tlucak, M., Sokol, R. J. & Martier, S. Underreporting of alcohol use in pregnancy.

_Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res._ 12, 506–511 (1988). Article Google Scholar * Jones, J., Jones, M., Plate, C. & Lewis, D. The detection of 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanol in

human dried blood spots. _Anal. Methods_ 3, 1101–1106 (2011). Article CAS Google Scholar * Jones, J. _et al._ Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry assay to detect ethyl

glucuronide in human fingernail: Comparison to hair and gender differences. _Am. J. Anal. Chem._ 3, 83–91 (2012). Article CAS Google Scholar * May, P. A. & Gossage, J. P. Maternal

risk factors for fetal alcohol spectrum disorders: not as simple as it might seem. _Alcohol Res. Health._ 34, 15–26 (2011). PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * May, P. A. _et al._

Maternal alcohol consumption producing fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASD): quantity, frequency, and timing of drinking. _Drug Alcohol Depend._ 133, 502–512 (2013). Article PubMed

Google Scholar * May, P. A. _et al._ Maternal nutritional status as a contributing factor for the risk of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. _Reprod. Toxicol._ 59, 101–108 (2016). Article

CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Warren, K. R., & Li, T. K. Genetic polymorphisms: impact on the risk of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. _Birth Defects Res. A Clin. Mol. Teratol_. 73,

195–203 (2005). * Dinan, T. G. & Cryan, F. J. The microbiome-gut-brain axis in health and disease. _Gastroenterol. Clin. N. Am._ 46, 77–89 (2017). Article Google Scholar * Gentile, C.

L. & Weir, T. L. The gut microbiota at the intersection of diet and human health. _Science_ 362, 776–780 (2018). Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Schroeder, B. O. &

Backhed, F. Signals from the gut microbiota to distant organs in physiology and disease. _Nat. Med._ 22, 1079–1089 (2016). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Wikoff, W. R. _et al._

Metabolomics analysis reveals large effects of gut microflora on mammalian blood metabolites. _Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A._ 106, 3698–3703 (2009). Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central

Google Scholar * Williamson, G., Kay, C. D. & Crozier, A. The bioavailability, transport, and bioactivity of dietary flavonoids: A review from a historical perspective. _Comp. Rev.

Food Sci. Food Saf._ 17, 1054–1110 (2018). Article Google Scholar * Blacher, E. _et al._ Potential roles of gut microbiome and metabolites in modulating ALS in mice. _Nature_ 572, 474–480

(2019). Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Hamaue, N. _et al._ Urinary isatin concentrations in patients with Parkinson’s disease determined by a newly developed HPLC-UV method.

_Res. Commun. Mol. Pathol. Pharmacol._ 108, 63–73 (2000). CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Olson, C. A. _et al._ The gut microbiota mediates the anti-seizure effects of the ketogenic diet.

_Cell_ 173, 1728–1741 (2018). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Rothhammer, V. _et al._ Microglial control of astrocytes in response to microbial metabolites. _Nature_

557, 724–728 (2018). Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Sampson, T. R. _et al._ Gut microbiota regulate motor deficits and neuroinflammation in a model of

Parkinson’s disease. _Cell_ 167, 1469–1480 (2016). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Valles-Colomer, M. _et al._ The neuroactive potential of the human gut microbiota

in quality of life and depression. _Nat. Microbiol._ 4, 623–632 (2019). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Vuong, H. E., Yano, J. M., Fung, T. C., & Hsiao, E. Y. The microbiome and

host behavior. _Annu. Rev. Neurosci_. 40, 21–49 (2017). * Jaglin, M. _et al_. Indole, a signaling molecule produced by the gut microbiota, negatively impacts emotional behaviors in rats.

_Front. Neurosci_. 12, 216. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2018.00216 (2018). * Caspani, G., Kennedy, S., Foster, J. A. & Swann, J. Gut microbial metabolites in depression: Understanding

the biochemical mechanisms. _Microb. Cell._ 6, 454–481 (2019). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Rothhammer, V. _et al._ Type I interferons and microbial metabolites of

tryptophan modulate astrocyte activity and central nervous system inflammation via the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. _Nat. Med._ 22, 586–597 (2016). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central

Google Scholar * Appeldoorn, M. M., Vincken, J. P., Aura, A. M., Hollman, P. C. & Gruppen, H. Procyanidin dimers are metabolized by human microbiota with 2-(3,4-dihydroxyphenyl)acetic

acid and 5-(3,4-dihydroxyphenyl)-gamma-valerolactone as the major metabolites. _J. Agric. Food Chem._ 57, 1084–1092 (2009). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Hsiao, E. Y. _et al._

Microbiota modulate behavioral and physiological abnormalities associated with neurodevelopmental disorders. _Cell_ 155, 1451–1463 (2013). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google

Scholar * Kelly, J. R. _et al._ Transferring the blues: Depression-associated gut microbiota induces neurobehavioural changes in the rat. _J. Psychiatr. Res._ 82, 109–118 (2016). Article

PubMed Google Scholar * Sharon, G. _et al._ Human gut microbiota from Autism Spectrum Disorder promote behavioral symptoms in mice. _Cell_ 177, 1600–1618 (2019). Article CAS PubMed

PubMed Central Google Scholar * Samuelson, D. R. _et al._ Intestinal microbial products from alcohol-fed mice contribute to intestinal permeability and peripheral immune activation.

_Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res._ 43, 2122–2133 (2019). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Bajaj, J. S. Alcohol, liver disease and the gut microbiota. _Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol.

Hepatol._ 16, 235–246 (2019). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Duan, Y. _et al._ Bacteriophage targeting of gut bacterium attenuates alcoholic liver disease. _Nature_ 575, 505–511 (2019).

Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Engen, P. A., Green, S. J., Voigt, R., Forsyth, C. B., & Keshavarzian, A. The gastrointestinal microbiome. Alcohol effects

on the composition of intestinal microbiota. _Alcohol Res._ 37, 223–236 (2015). * Mutlu, E. A. _et al._ Colonic microbiome is altered in alcoholism. _Am. J. Physio.l Gastrointest. Liver

Physiol_. 302, G966-G978 (2012). * Szabo, G. Gut-liver axis in alcoholic liver disease. _Gastroenterol._ 148, 30–36 (2015). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Pascual, M. _et al._ TLR4

response mediates ethanol-induced neurodevelopment alterations in a model of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. _J. Neuroinflammation._ 14, 145. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12974-017-0918-2

(2017). * Shukla, P. K., Meena, A. S., Rao, R. & Rao, R. Deletion of TLR-4 attenuates fetal alcohol exposure-induced gene expression and social interaction deficits. _Alcohol._ 73, 73–78

(2018). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Amos-Kroohs, R. M., Nelson, D. W., Hacker, T. A., Yen, C. E., & Smith, S. M. Does prenatal alcohol exposure cause a

metabolic syndrome? (Non-)evidence from a mouse model of fetal alcohol spectrum disorder. _PLoS One._ 28, 13:e0199213.https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0199213. (2018). * Laukens, D.,

Brinkman, B. M., Raes, J., De Vos, M. & Vandenabeele, P. Heterogeneity of the gut microbiome in mice: Guidelines for optimizing experimental design. _FEMS Microbiol. Rev._ 40, 117–132

(2016). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Dobson, C. C. _et al._ Impact of molecular interactions with phenolic compounds on food polysaccharides functionality. _Adv. Food Nutr. Res._

90, 135–179 (2019). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Del Rio, D. _et al._ Dietary (poly)phenolics in human health: Structures, bioavailability, and evidence of protective effects

against chronic diseases. _Antioxidants Redox Signaling._ 18, 1818–1892 (2013). Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Fiorucci, S. & Distrutti, E. Bile acid-activated

receptors, intestinal microbiota, and the treatment of metabolic disorders. _Trends Mol. Med._ 21, 702–714 (2015). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Tseng, A. M. _et al._;

Collaborative Initiative on Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders. Maternal circulating miRNAs that predict infant FASD outcomes influence placental maturation. _Life Sci. Alliance_. 2,

e201800252. https://doi.org/10.26508/lsa.201800252 (2019). * Impact of alcohol consumption during pregnancy. Bodnar, T. S. et al. Collaborative Initiative on Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders

(CIFASD). Altered maternal immune networks are associated with adverse child neurodevelopment. _Brain Behav. Immun._ 73, 205–215 (2018). Article CAS Google Scholar * Martin, F. P. _et

al._ A top-down systems biology view of microbiome-mammalian metabolic interactions in a mouse model. _Mol. Syst. Biol._ 3, 112. https://doi.org/10.1038/msb4100153 (2007). Article CAS

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Rothschild, D. _et al._ Environment dominates over host genetics in shaping human gut microbiota. _Nature_ 555, 210–215 (2018). Article ADS CAS

PubMed Google Scholar * Manach, C., Scalbert, A., Morand, C., Remesy, C. & Jimenez, L. Polyphenols: food sources and bioavailability. _Am. J. Clin. Nutr_ 79, 727–747 (2004). Article

CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Pinto, P. & Santos, C. N. Worldwide (poly)phenol intake: assessment methods and identified gaps. _Eur. J. Nutr._ 56, 1393–1408 (2017). Article CAS PubMed

Google Scholar * Gibson, G. R. _et al._ Expert consensus document: The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) consensus statement on the definition and

scope of prebiotics. _Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol._ 14, 491–502 (2017). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Sayin, S. I. _et al._ Gut microbiota regulates bile acid metabolism by

reducing the levels of tauro-beta-muricholic acid, a naturally occurring FXR antagonist. _Cell Metab._ 17, 225–235 (2013). Article MathSciNet CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Xie, G. _et

al._ Alteration of bile acid metabolism in the rat induced by chronic ethanol consumption. _FASEB J._ 27, 3583–3593 (2013). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Kakiyama,

G. _et al._ Colonic inflammation and secondary bile acids in alcoholic cirrhosis. _Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol._ 306, G929–G937 (2014). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central

Google Scholar * Kang, D. J. _et al._ Gut microbial composition can differentially regulate bile acid synthesis in humanized mice. _Hepatol. Commun._ 1, 61–70 (2017). Article MathSciNet

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Howard, P. J. & Murphy, G. M. Bile acid stress in the mother and baby unit. _Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol._ 15, 317–321 (2003). Article

CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Islam, K. B. _et al._ Bile acid is a host factor that regulates the composition of the cecal microbiota in rats. _Gastroenterology_ 141, 1773–1781 (2011).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Buffie, C. G. _et al._ Precision microbiome reconstitution restores bile acid mediated resistance to Clostridium difficile. _Nature_ 517, 205–208

(2015). Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Kane, C. J., Phelan, K. D. & Drew, P. D. Neuroimmune mechanisms in fetal alcohol spectrum disorder. _Dev. Neurobiol._ 72, 1302–1316

(2012). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Ornoy, A., Reece, E. A., Pavlinkova, G., Kappen, C. & Miller, R. K. Effect of maternal diabetes on the embryo, fetus, and

children: congenital anomalies, genetic and epigenetic changes and developmental outcomes. _Birth Defects Res. C Embryo Today._ 105, 53–72 (2015). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar *

Wang, P. _et al._ Targeted metabolomics analysis of maternal-placental-fetal metabolism in pregnant swine reveals links in fetal bile acid homeostasis and sulfonation capacity. _Am. J.

Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol._ 317, G8–G16 (2019). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Tang, R. M. Y., Cheah, I.K.-M., Yew, T. S. K. & Halliwell, B. Distribution and

accumulation of dietary ergothioneine and its metabolites in mouse tissues. _Sci. Rep._ 8, 1601. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-20021-z (2018). Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central

Google Scholar * Venkatesh, M. _et al._ Symbiotic bacterial metabolites regulate gastrointestinal barrier function via the xenobiotic sensor PXR and Toll-like receptor 4. _Immunity_ 41,

296–310 (2014). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Abildgaard, A., Elfving, B., Hokland, M., Wegener, G. & Lund, S. Probiotic treatment reduces depressive-like

behaviour in rats independently of diet. _Psychoneuroendocrinology._ 79, 40–48 (2017). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Bhattacharya, S. K., Mitra, S. K. & Acharya, S. B.

Anxiogenic activity of isatin, a putative biological factor, in rodents. _J. Psychopharmacol._ 5, 202–206 (1991). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Schroeder, J. C. _et al._ The uremic

toxin 3-indoxyl sulfate is a potent endogenous agonist for the human aryl hydrocarbon receptor. _Biochemistry_ 49, 393–400 (2010). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Reeves, P. G.,

Nielsen, F. H. & Fahey, G. C. Jr. AIN-93 purified diets for laboratory rodents: final report of the American Institute of Nutrition ad hoc writing committee on the reformulation of the

AIN-76A rodent diet. _J. Nutr._ 123, 1939–1951 (1993). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Benjamini, Y. & Hochberg, Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful

approach to multiple testing. _J. R. Stat. Soc. B._ 289–300 (1995). * OmicSoft Corporation. OmicSoft ArraySuite software. OmicSoft Corporation, Version 8. (2015). * R Core Team. R: A

Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. https://www.R-project.org (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2020). * Lê, S., Josse, J. & Husson, F. FactoMineR: An R package

for multivariate analysis. _J. Stat. Softw._ 25, 1–18 (2008). Article Google Scholar * Kassambara, A. & Mundt, F. factoextra: extract and visualize the results of multivariate data

analyses. R package version 1.0.7. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=factoextra (2020). * Wickham, H. ggplot2: elegant graphics for data analysis. (Springer-Verlag, 2016). * Shannon, P. _et

al._ Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. _Genome Res._ 13, 2498–2504 (2003). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

* Gustavsen, J.A., Pai, S., Isserlin, R., Demchak, B., & Pico, A.R. RCy3: Network biology using Cytoscape from within R. _F1000Research_ https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.20887

(2019). * Settle, B., Otasek, D., Morris, J.H., Demchak, B. AMatReader: importing adjacency matrices via Cytoscape automation. _F1000Research_ 7 (2018). Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Supported by NIH awards R01 AA011085 and R01 AA022999 (both to SMS); F32 AA027121 (STCK), T32 DK007686 (KKH), and internal funds from the UNC-NRI. Citation for the untargeted metabolite

analysis described in Supplementary Methods S1 is Ramamoorthy, Sivapriya. mView Report on UNCH-06-18VW+. Metabolon, Inc. Personal communication, October 31, 2018. AUTHOR INFORMATION AUTHORS

AND AFFILIATIONS * Department of Nutrition, UNC Nutrition Research Institute, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 500 Laureate Way, Kannapolis, NC, 28082, USA Manjot S. Virdee,

Nipun Saini, Sze Ting Cecilia Kwan, Kaylee K. Helfrich, Sandra M. Mooney & Susan M. Smith * Department of Food Bioprocessing and Nutrition Sciences, Plants for Human Health Institute,

North Carolina State University, Kannapolis, NC, 28081, USA Colin D. Kay & Andrew P. Neilson Authors * Manjot S. Virdee View author publications You can also search for this author

inPubMed Google Scholar * Nipun Saini View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Colin D. Kay View author publications You can also search for

this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Andrew P. Neilson View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Sze Ting Cecilia Kwan View author publications

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Kaylee K. Helfrich View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Sandra M. Mooney View

author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Susan M. Smith View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar

CONTRIBUTIONS S.M.S., N.S., S.T.C.K., and K.K.H. designed the experiment; N.S., S.T.C.K., and K.K.H. generated the samples for analysis. M.S.V. analyzed the data and generated all figures.

S.M.S., S.M.M., C.D.K., and A.P.N. interpreted the results. S.M.S. and M.S.V. wrote the manuscript, with input from C.D.K., A.P.N., and S.M.M. All authors reviewed and approved the

manuscript. CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to Susan M. Smith. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS The authors declare no competing interests. The datasets generated during and/or

analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION PUBLISHER'S NOTE Springer Nature remains neutral with regard

to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS OPEN ACCESS This article is licensed

under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate

credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article

are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons

licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of

this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Virdee, M.S., Saini, N., Kay, C.D. _et al._ An enriched

biosignature of gut microbiota-dependent metabolites characterizes maternal plasma in a mouse model of fetal alcohol spectrum disorder. _Sci Rep_ 11, 248 (2021).

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-80093-8 Download citation * Received: 11 June 2020 * Accepted: 14 December 2020 * Published: 08 January 2021 * DOI:

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-80093-8 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not

currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative