Play all audios:

ABSTRACT Delayed bleeding is a major issue in patients with high-grade splenic injuries who receive non-operative management (NOM). While only few studies addressed the clinical

manifestations of delayed bleeding in these patients. We reviewed the patients with high-grade splenic injuries presented with delayed bleeding, defined as the need for salvage procedures

following NOM. There were 138 patients received NOM in study period. Fourteen of 107 patients in the SAE group and 3 of 31 patients in the non-embolization group had delayed bleeding. Among

the 17 delayed bleeding episodes, 6 and 11 patients were salvaged by splenectomy and SAE, respectively. Ten (58.9%, 10/17) patients experienced bleeding episodes in the intensive care unit

(ICU), whereas seven (41.1%, 7/17) experienced those in the ward or at home. The clinical manifestations of delayed bleeding were a decline in haemoglobin levels (47.1%, 8/17), hypotension

(35.3%, 6/17), tachycardia (47.1%, 8/17), new abdominal pain (29.4%, 5/17), and worsening abdominal pain (17.6%, 3/17). For the bleeding episodes detected in the ICU, a decline in

haemoglobin (60%, 6/10) was the main manifestation. New abdominal pain (71.43%, 5/7) was the main presentation when the patients left the ICU. In conclusion, abdominal pain was the main

early clinical presentation of delayed bleeding following discharge from the ICU or hospital. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS THE PREVALENCE OF EARLY CONTAINED VASCULAR INJURY OF

SPLEEN Article Open access 04 April 2024 COMPARATIVE EFFECTIVENESS OF ANGIOEMBOLIZATION VERSUS OPEN SURGERY IN PATIENTS WITH BLUNT SPLENIC INJURY Article Open access 16 April 2024 A

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW OF EMERGENCY ROOM LAPAROTOMY IN PATIENTS WITH SEVERE ABDOMINAL TRAUMA Article Open access 22 January 2025 INTRODUCTION Approximately a quarter of blunt abdominal traumas

result in splenic injury, the most frequently encountered solid organ injury1. Over the past two decades, non-operative management (NOM) has been recommended as the primary treatment choice

for haemodynamically stable patients to preserve splenic function2,3,4,5. In Taiwan, the NOM rate of splenic injury increased from 56 to 73% in tertiary centres3,5,6. In addition, the

success rate of NOM can be up to 90%3,4,7. Close monitoring of patients with high-grade splenic injury receiving NOM is necessary, as this group of patients is at a higher risk of treatment

failure3,4,8,9. The failure rate of NOM ranges from 16.7 to 25.0%, depending on patient conditions9,10, such as injury severity score > 24, splenic injury grade > 2, and age > 40

years2,11,12,13. The timing of NOM failure ranges from hours to weeks after an injury14and there are no factors that can be used to predict this accurately. Continuous monitoring is

necessary, as the risk of bleeding remains even after discharge2. Therefore, identifying the signs and symptoms of bleeding after NOM is important for early detection, early haemostasis, and

the prevention of unfavourable outcomes14,15. However, few studies have discussed the clinical manifestations of delayed splenic bleeding after NOM14,15,16. Here, we conducted a review of

the outcomes in patients with high-grade splenic injuries over a 10 years period. This study aimed to identify the clinical manifestations of bleeding in patients with a high-grade splenic

injury who received NOM. MATERIAL AND METHODS STUDY PARTICIPANTS We conducted a retrospective study to review the medical records of patients with high-grade blunt splenic injury at the

National Cheng Kung University Hospital (NCKUH) from 1 January 2010 to 31 December 2020. This study was approved by our institutional review board of National Cheng Kung University Hospital

(IRB No. B-ER-111-120) and the requirement for informed consent was waived. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. We recruited patients with

high-grade splenic injury from the trauma registry data bank. The severity of the injury was defined using the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST) Organ Injury Scale. All

patients with splenic injury grade ≥ 3 were defined as having a high-grade splenic injury and were included in this study. The exclusion criteria were age < 16 years and splenectomy

performed within 6 h of presentation to the emergency room. Data were obtained on patient demography, outcome, clinical management of the splenic injury, haemodynamic status, and laboratory

test results. DEFINITION OF NON-OPERATIVE MANAGEMENT AND DELAYED BLEEDING Patients with high-grade splenic injury who did not undergo splenectomy within the first 6 h after presenting to the

emergency department were considered to have received NOM. Delayed bleeding was defined in patients who received NOM initially and required a salvage procedure, including splenectomy or

splenic artery embolization (SAE). Patients who underwent angiography after NOM to evaluate any potential bleeding but did not receive SAE were classified as having no delayed bleeding.

NON-OPERATIVE MANAGEMENT FOR SPLENIC INJURY AT NCKUH Most patients with splenic injuries received NOM in our hospital unless they presented with an unstable haemodynamic status (systolic

blood pressure < 90 mmHg). Angiography was indicated when the patients had contrast extravasation on computed tomography (CT), high-grade splenic injury, transient hypotension with a

rapid fluid response, and a persistent decrease in haemoglobin level. Patients with high-grade splenic injury who received SAE or had grade IV–V splenic injury without embolization were

observed in the intensive care unit (ICU) for 24–48 h with real-time monitoring and regular measuring of haemoglobin levels every 6–8 h. Patients who developed an unstable haemodynamic

status had an indication for laparotomy. A persistent drop in haemoglobin levels, usually > 2 gm/dL, still requiring transfusion in the ICU was an indication for angiography to evaluate

the potential need for SAE if the haemodynamic status was stable. Then, the patients were observed in the ward if they did not have severe associated injuries. Once the patients had signs

and symptoms of delayed splenic injury and bleeding in the ward, they underwent a CT scan to evaluate the presence of active bleeding or new haematoma in the peritoneal cavity. Repeat

angiography was the first choice of salvage procedure unless the patient had an unstable haemodynamic status. STATISTICAL ANALYSIS Continuous variables were analysed by Student’s _t_ test,

and categorical variables were analysed by chi-square tests. _P-_value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS Statistics for

Windows, Version 17.0. (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). ETHICAL APPROVAL AND INFORMED CONSENT This study was approved by our institutional review board and the requirement for informed consent

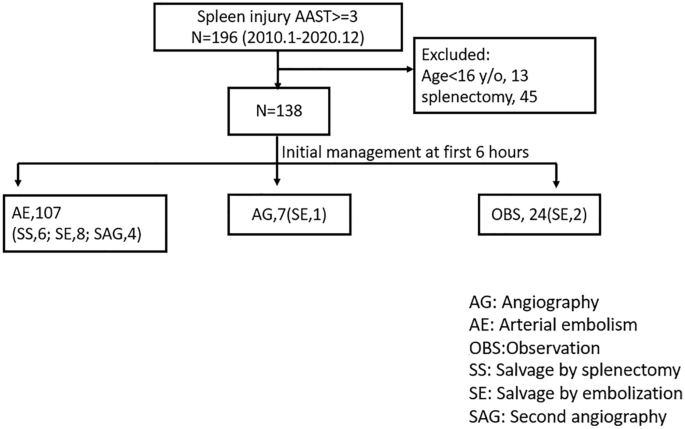

was waived. PRESENTATION This paper had been presented at the 2021 Annual meeting of Taiwan Surgical Association. RESULTS A total of 196 patients presented with high-grade splenic injury.

We excluded 13 patients aged < 16 and 45 patients who underwent splenectomy. Among the 138 patients who received NOM, 107 (77.5%) were initially managed with SAE and seven patients

received angiography without embolization. Of the rest, 17 (12.3%) patients experienced bleeding episodes after NOM: 6 were salvaged by splenectomy and 11 by SAE. Four patients underwent

angiography without embolization (Fig. 1). There were no statistically significant differences in age, sex, and injury mechanism between the groups that received SAE and those that did not

receive embolization (NE). The SAE group had more patients with shock index > 0.9 than the NE group, but this difference was not statistically significant (29.9% vs. 19.4%, _P_ = 0.101).

Compared with the NE group, the SAE group was associated with more severe haemoperitoneum (30.0% vs. 16.1%, _P_ = 0.010), fewer grade III splenic injuries (43.9% vs. 74.2%, _P_ = 0.012), and

more arterial extravasation (47.7% vs. 25.8%, _P_ = 0.030) (Table 1). For patients who had bleeding episodes after initial NOM, the time to the salvage procedure ranged from 8 h to 28 days

(Fig. 2). Eleven (64.7%) salvage procedures were performed within 5 days after injury, while six patients (35.3%) received salvage procedures 9 to 28 days after injury. Six (35.3%) patients

presented with blood pressure < 90 mmHg, eight (47.1%) experienced tachycardia (heart rate > 120 bpm, 4 h before salvage), and eight (47.1%) presented with decreased haemoglobin.

Moreover, eight (47.1%) patients had the symptoms of abdominal pain: three (17.6%) presented with worsening and five (29.4%) with new abdominal pain. All patients who had bleeding episodes

after NOM were successfully salvaged by either surgery or embolization in our hospital (Table 2). Ten (58.9%) patients experienced bleeding episodes in the ICU, while seven (41.1%) patients

experienced bleeding episodes when they were in the ward or at home. A decreased haemoglobin level (> 2 gm/dL) was the main manifestation of bleeding episodes detected in the ICU. New

abdominal pain was the main presentation (71.4%) when a bleeding episode occurred in the ward or at home. When a bleeding episode occurred after day 9, all patients experienced abdominal

pain (Table 2, Fig. 3). DISCUSSION This retrospective study analysed our experience with the management of delayed bleeding complications of high-grade blunt splenic injury after NOM.

Seventeen of 138 (12.3%) high-grade splenic injuries required salvage procedures following NOM. Eleven and six patients were successfully salvaged by repeat SAE and splenectomy,

respectively. Abdominal pain was the main manifestation of delayed bleeding for patients following discharge from the ICU. This is an important early warning sign of delayed bleeding from a

splenic injury, especially as the patient leaves the hospital. To the best of our knowledge, few studies have reported on bleeding complications of splenic injury after NOM; these studies

include 17 cases with delayed bleeding complications, only two of which included > 10 cases14,17. The current study demonstrated that abdominal pain is an important warning sign of

delayed bleeding of splenic injury, especially in patients discharged from the ICU; this is an important manifestation that has rarely been emphasised in the literature. Arterial

embolization has been widely used for solid organ injury and can significantly increase the success rate of NOM for spleen injury10. According to recent studies, SAE resulted in > 90%

success rate of NOM3,4. However, SAE could not totally prevent delayed bleeding episodes in patients receiving NOM. Approximately 17–25% of patients with splenic injuries had bleeding

episodes after SAE9. Failure of NOM resulted in higher rates of mortality or prolonged hospitalisation14. However, there were no differences in the success rate of NOM or incidence of

adverse events between patients who received prophylactic SAE and those who received indicated SAE3. In the current study, 17 of 138 (12.3%) patients needed salvage procedures after the

initial NOM. Close monitoring of the signs and symptoms of bleeding is crucial for patients receiving NOM to detect bleeding episodes early and avoid unfavourable outcomes. Delayed diagnosis

of bleeding episodes can be dangerous or even deadly. Peitzman et al. reported 10 mortalities among 78 splenic injury patients with NOM failure4,14,15,18, and a 5–15% mortality rate have

been reported by other studies18,19,20. Romeo et al. reported two cases of delayed splenic bleeding presenting with haemorrhagic shock, who were then admitted for several months21. Kodikara

also reported a death due to delayed splenic rupture-related haemorrhagic shock22. Delayed bleeding episodes may result in acute haemodynamic instability, which significantly increases

morbidity and mortality and is a risk factor for the development of multiple organ dysfunction23. Most delayed bleeding episodes after the splenic injury occurred in the early period of NOM.

Studies showed that 80–95% of splenic injuries had delayed bleeding episodes within 72 h of injury, and 18% of patients had failed NOM longer than 5 days after admission4,14,24. Thus,

patients with high-grade splenic injury require close observation by real-time monitoring in the ICU. In our protocol, the patients were observed in the ICU for 24–48 h with regular

monitoring of haemoglobin levels every 6–8 h after SAE. The bleeding episodes in our study occurred from 8 to 28 days after the start of NOM. Among patients who had bleeding episodes, 11

(64.7%) experienced them within 5 days, and 15 patients (88.2%) within 2 weeks of the injury. Several studies have suggested that longer observation periods should be adopted, but the need

for observation eventually ended in up to 80% of patients within 14 days and in 95% within 21 days24,25,26,27. Ten (58.9%) patients experienced bleeding episodes in the ICU, while seven

(41.2%) patients experienced bleeding episodes in the ward or at home. Most of the patients were discharged within one week. Prolonged observation in hospitals may not be practical and could

waste medical resources. Accordingly, educating patients and their families about early signs of bleeding is relevant and crucial. Abdominal pain may be a reliable manifestation of delayed

bleeding in patients receiving NOM. In 1977, Olsen et al. demonstrated ten cases of delayed splenic rupture and showed that most of them experienced abdominal pain in different durations,

patterns, and severity17. Farhat reported one case of delayed splenic rupture and mentioned that abdominal pain was common28. Peitzman et al. reported 78 cases of splenic injury with NOM

failure, and the presentations of delayed bleeding in their study included haemodynamic decompensation (15%), decreased haemoglobin (36.5%), new abdominal pain (5%), worsening of abdominal

pain (36.5%), and persistent tachycardia (16.2%)14. These were comparable with our results. According to the literature and our experience, the pattern of pain involved sudden onset of

severe pain over the upper-left quadrant area29. Additionally, our study demonstrated that the main manifestations of delayed bleeding changed at different time periods (in the ICU, the ward

or at home). Decreased haemoglobin levels were the main manifestation in patients requiring a salvage procedure in the ICU. However, new abdominal pain was the main presentation (71.4%)

when a bleeding episode happened in the ward or at home. Only approximately one-third of patients with delayed bleeding had hypotension. For this reason, focusing on the signs of

haemodynamic status may overlook patients with delayed bleeding. Here, three patients with delayed bleeding were unnoticed in the emergency department when they returned after discharge as

they presented with symptoms of sudden abdominal pain rather than hypotension or a decline in haemoglobin levels. Recognising abdominal pain as one of the main presentations of delayed

splenic bleeding is crucial for early diagnosis to avoid unfavourable outcomes. Additionally, Kofinas et al. mentioned the pattern of pain was left lower thorax and upper abdominal pain or

tenderness in 202129. It a similar clinical case of delayed splenic rupture, in which a young female received non-operative treatment initially similar clinical situation. Similarly, sudden

onset of severe abdominal pain at left upper quadrant was the common pattern in our experience. Currently, no definitive guidelines have been established for identifying delayed bleeding

following a splenic injury that has been treated with NOM. The World Society of Emergency Surgery classification of splenic trauma and the management guidelines are evidence-based2 and

recommended angiography, angioembolization, and splenectomy as salvage strategies for bleeding after NOM based on different indications. Operative management should be applied in cases of

haemodynamic instability or if associated intra-abdominal injuries requiring surgical treatment are present30. The use of SAE for delayed splenic bleeding is supported by some evidence, for

example, Liu et al. reported that five of six patients with delayed splenic bleeding were successfully salvaged by SAE31. Here, 17 of 138 (12.3%) patients received NOM for high-grade splenic

injury and later needed salvage procedures, and 11 of the 17 patients with delayed bleeding were successfully salvaged by repeat embolization. Repeating SAE for selected patients with

delayed splenic bleeding is a safe and feasible strategy. The current study has several limitations. First, this was a retrospective study, and the patients’ symptoms and haemodynamic data

were collected by reviewing their electronic medical records. Symptoms of abdominal pain could have been overlooked and incompletely recorded. However, haemodynamic data such as hypotension

were less likely to be missed. Nevertheless, this did not affect our conclusion that abdominal pain was the main manifestation of delayed bleeding following discharge from the ICU. Second,

some patients with delayed bleeding may have received treatment at other hospitals. We believe this probability to be low because most patients with a high-grade splenic injury received

follow-up at our outpatient department, and it may not have affected the results of the current study. Third, the sample size was small as most previous studies were case reports. Only one

study had more cases of delayed bleeding than the current study. Fourth, we frequently checked haemoglobin levels in the ICU and identified patients with signs of bleeding while the

haemodynamic status was stable. Angiography usually shows oozing of the contrast in the spleen parenchyma. This type of bleeding may stop spontaneously, and our protocol may increase the

incidence of delayed bleeding. However, the bleeding episodes only accounted for 12.3% of all the high-grade splenic injuries receiving NOM, which was not higher than that observed in

previous studies4,6,9,14,31. Delayed splenic bleeding is unpredictable and may occur within 4 weeks of the injury. The common clinical manifestations of delayed splenic bleeding include

tachycardia, hypotension, a decline in haemoglobin levels, and abdominal pain. Abdominal pain is the main early clinical presentation of delayed bleeding after a patient leaves the ICU and

hospital, and this is the first study to highlight its importance as an early clinical manifestation of delayed bleeding. Emphasising the importance of abdominal pain as an alarming

presentation of delayed bleeding can help patients determine when to return to the hospital for timely management. DATA AVAILABILITY The data that support the findings of this study are

available from National Cheng Kung University Hospital, but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly

available. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of correspondence. REFERENCES * El-Matbouly, M. _et al._ Blunt splenic trauma: Assessment,

management and outcomes. _Surgeon_ 14, 52–58 (2016). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Coccolini, F. _et al._ Splenic trauma: WSES classification and guidelines for adult and pediatric

patients. _World J. Emerg. Surg._ 12, 40 (2017). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Arvieux, C. _et al._ Effect of prophylactic embolization on patients With blunt trauma at

high risk of splenectomy: A randomized clinical trial. _JAMA Surg._ 155, 1102–1111 (2020). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Fodor, M. _et al._ Non-operative management of

blunt hepatic and splenic injury: A time-trend and outcome analysis over a period of 17 years. _World J. Emerg. Surg._ 14, 29 (2019). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar *

Scarborough, J. E. _et al._ Nonoperative management is as effective as immediate splenectomy for adult patients with high-grade blunt splenic injury. _J. Am. Coll. Surg._ 223, 249–258

(2016). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Liao, C. A. _et al._ Hospital Level variations in the trends and outcomes of the nonoperative management of splenic injuries—A nationwide cohort

study. _Scand. J. Trauma Resusc. Emerg. Med._ 27, 4 (2019). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Bhangu, A., Nepogodiev, D., Lal, N. & Bowley, D. M. Meta-analysis of

predictive factors and outcomes for failure of non-operative management of blunt splenic trauma. _Injury_ 43, 1337–1346 (2012). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Hsieh, T. M., Liu, C. T.,

Wu, B. Y. & Hsieh, C. H. Is strict adherence to the nonoperative management protocol associated with better outcome in patients with blunt splenic injuries? A retrospective comparative

cross-sectional study. _Int. J. Surg._ 69, 116–123 (2019). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Requarth, J. A., D’Agostino, R. B. Jr. & Miller, P. R. Nonoperative management of adult

blunt splenic injury with and without splenic artery embolotherapy: A meta-analysis. _J. Trauma._ 71, 898–903 (2011). PubMed Google Scholar * Crichton, J. C. I. _et al._ The role of

splenic angioembolization as an adjunct to nonoperative management of blunt splenic injuries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. _J. Trauma Acute Care Surg._ 83, 934–943 (2017). Article

PubMed Google Scholar * Olthof, D. C., Joosse, P., van der Vlies, C. H., de Haan, R. J. & Goslings, J. C. Prognostic factors for failure of nonoperative management in adults with

blunt splenic injury: A systematic review. _J. Trauma Acute Care Surg._ 74, 546–557 (2013). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Linnaus, M. E. _et al._ Failure of nonoperative management of

pediatric blunt liver and spleen injuries: A prospective Arizona-Texas-Oklahoma-Memphis-Arkansas Consortium study. _J. Trauma Acute Care Surg._ 82, 672–679 (2017). Article PubMed Google

Scholar * Stassen, N. A. _et al._ Selective nonoperative management of blunt splenic injury: An eastern association for the surgery of trauma practice management guideline. _J. Trauma Acute

Care Surg._ 73(Suppl 4), S294-300 (2012). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Peitzman, A. B. _et al._ Failure of observation of blunt splenic injury in adults: Variability in practice and

adverse consequences. _J. Am. Coll. Surg._ 201, 179–187 (2005). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Kratzke, I. M., Strassle, P. D., Schiro, S. E., Meyer, A. A. & Brownstein, M. R. Risks

and realities of delayed splenic bleeding. _Am. Surg._ 85, 904–908 (2019). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Freiwald, S. Late-presenting complications after splenic trauma. _Perm. J._ 14,

41–44 (2010). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Olsen, W. R. & Polley, T. Z. A second look at delayed splenic rupture. _Arch. Surg._ 112, 422–425 (1977). Article CAS

PubMed Google Scholar * Baillie, R. W. Delayed haemorrhage following traumatic rupture of the normal spleen simulating spontaneous rupture. _Postgrad. Med. J._ 28, 494–496 (1952). Article

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Kluger, Y. _et al._ Delayed rupture of the spleen–myths, facts, and their importance: Case reports and literature review. _J. Trauma_ 36,

568–571 (1994). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Costa, G. _et al._ The epidemiology and clinical evaluation of abdominal trauma. An analysis of a multidisciplinary trauma registry.

_Ann. Ital. Chir._ 81, 95–102 (2010). PubMed Google Scholar * Romeo, L. _et al._ Delayed rupture of a normal appearing spleen after trauma: Is our knowledge enough? Two case reports. _Am.

J. Case Rep._ 21, e919617 (2020). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Kodikara, S. Death due to hemorrhagic shock after delayed rupture of spleen: A rare phenomenon. _Am. J.

Forensic Med. Pathol._ 30, 382–383 (2009). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Harbrecht, B. G. Is anything new in adult blunt splenic trauma?. _Am. J. Surg._ 190, 273–278 (2005). Article

PubMed Google Scholar * Smith, J., Armen, S., Cook, C. H. & Martin, L. C. Blunt splenic injuries: Have we watched long enough?. _J. Trauma_ 64, 656–663 (2008). PubMed Google Scholar

* Gamblin, T. C., Wall, C. E. Jr., Royer, G. M., Dalton, M. L. & Ashley, D. W. Delayed splenic rupture: Case reports and review of the literature. _J. Trauma_ 59, 1231–1234 (2005).

Article PubMed Google Scholar * Sizer, J. S., Wayne, E. R. & Frederick, P. L. Delayed rupture of the spleen. Review of the literature and report of six cases. _Arch. Surg._ 92,

362–366 (1966). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Leeper, W. R. _et al._ Delayed hemorrhagic complications in the nonoperative management of blunt splenic trauma: Early screening leads

to a decrease in failure rate. _J. Trauma Acute Care Surg._ 76, 1349–1353 (2014). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Farhat, G. A., Abdu, R. A. & Vanek, V. W. Delayed splenic rupture:

Real or imaginary?. _Am. Surg._ 58, 340–345 (1992). CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Kofinas, A. G. _et al._ Non-operative management of delayed splenic rupture 4 months following blunt

abdominal trauma. _Am. J. Case Rep._ 21(22), e932577 (2021). Google Scholar * Olthof, D. C., van der Vlies, C. H. & Goslings, J. C. Evidence-based management and controversies in blunt

splenic trauma. _Curr. Trauma Rep._ 3, 32–37 (2017). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Liu, P. P. _et al._ Use of splenic artery embolization as an adjunct to

nonsurgical management of blunt splenic injury. _J. Trauma_ 56, 768–772 (2004). Article PubMed Google Scholar Download references AUTHOR INFORMATION Author notes * These authors

contributed equally: Tsung-Han Yang and Chih-Jung Wang. AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * School of Medicine, College of Medicine, National Cheng Kung University, Tainan, Taiwan Yu-Cheng Su *

Department of Surgery, National Cheng Kung University Hospital, National Cheng Kung University, Tainan, Taiwan Chia-Yu Ou * Division of Trauma, Department of Surgery, College of Medicine,

National Cheng Kung University Hospital, National Cheng Kung University, No. 138, Sheng Li Road, Tainan, Taiwan Tsung-Han Yang, Kuo-Shu Hung, Chih-Jung Wang & Yi-Ting Yen * Division of

General Surgery, Department of Surgery, National Cheng Kung University Hospital, Tainan, Taiwan Chun-Hsien Wu & Yan-Shen Shan * Institute of Clinical Medicine, College of Medicine,

National Cheng Kung University, Tainan, Taiwan Yan-Shen Shan Authors * Yu-Cheng Su View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Chia-Yu Ou View

author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Tsung-Han Yang View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar *

Kuo-Shu Hung View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Chun-Hsien Wu View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google

Scholar * Chih-Jung Wang View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Yi-Ting Yen View author publications You can also search for this author

inPubMed Google Scholar * Yan-Shen Shan View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CONTRIBUTIONS Y.C.S., C.Y.O., C.J.W., Y.S.S.: design the study.

Y.C.S., C.Y.O., K.S.H., C.H.W.: collected data. Y.C.S., C.J.W., T.H.Y., Y.T.Y.: wrote the manuscript. C.Y.O., T.H.Y.: performed the analysis. All authors review the manuscript. CORRESPONDING

AUTHOR Correspondence to Chih-Jung Wang. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS The authors declare no competing interests. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION PUBLISHER'S NOTE Springer Nature

remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS OPEN ACCESS This article is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original

author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the

article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your

intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence,

visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Su, YC., Ou, CY., Yang, TH. _et al._ Abdominal pain is a main manifestation

of delayed bleeding after splenic injury in patients receiving non-operative management. _Sci Rep_ 12, 19871 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-24399-9 Download citation * Received:

24 July 2022 * Accepted: 15 November 2022 * Published: 18 November 2022 * DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-24399-9 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be

able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing

initiative