Play all audios:

ABSTRACT This study assesses the durability of coated and uncoated concrete surfaces protected with four different coating materials: water-soluble (BW), solvent-based (BR), mineral (MI),

and epoxy (EP). The durability assessment includes evaluating the absorption rate of water, pull-off adhesion strength, and coating material thickness. Concrete samples were subjected to

immersion in regular water and a 7% urea solution, followed by cyclic freezing and thawing. Furthermore, the diffusion of chloride ions in concrete was evaluated using the impressed voltage

method, with the samples exposed to the aging process immersed in a 3.5% NaCl solution. The results indicate that EP and BW coatings were significantly affected by the presence of urea and

freeze–thaw cycles, resulting in a 43% and 47% reduction in pull-off adhesion strength, respectively. Notably, the MI-coated concrete samples exposed to urea solution and the freeze–thaw

cycles exhibited a significant reduction in the absorption rate due to the accumulation of crystals on the coating surface, resulting in reduced porosity of the material. SIMILAR CONTENT

BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS MECHANICAL AND PHYSICAL ASSESSMENT OF EPOXY, MINERAL, SOLVENT-BASED, AND WATER-SOLUBLE COATING MATERIALS Article Open access 11 August 2022 INVESTIGATION OF THE EFFECT

OF FLY ASH CONTENT ON THE BONDING PERFORMANCE OF CFRP-CONCRETE INTERFACE IN SULFATE ENVIRONMENT Article Open access 19 October 2022 EFFECTS OF DODECYL AMIDE, NANO CALCIUM CARBONATE, AND DRY

RESIN ON ASPHALT CONCRETE COHESION AND ADHESION FAILURES IN MOISTURE CONDITIONS Article Open access 25 April 2025 INTRODUCTION The durability of concrete structures embedded in soil is

primarily influenced by the porosity of the concrete and the chemical properties of the soil1. Concrete porosity directly affects the transport of chlorides, sulfates, CO2, leading to steel

corrosion, cracking, and a reduced life span of reinforced concrete structures2,3. Reinforced concrete structures face challenges in various regions worldwide due to unfavorable

environmental conditions. Moreover, these structures are additionally affected by soil contamination, resulting from various human industries such as energy, transport, construction, mining,

and others. This contamination, combined with the impacts of climate change, accelerates the deterioration of reinforced concrete4,5. During the service life of concrete structures, damage

occurs due to chemical attacks and aggressive environments. The combustion of fuels, resulting in sulfuric acid, along with hydrochloric acid, aluminum chloride, and calcium bisulfite, leads

to rapid concrete deterioration6. The presence of salts, sulfates, and alkalis contributes to leaching, increasing porosity and weakening the concrete matrix7. Additionally, freeze–thaw

cycles at different temperatures generate hydraulic pressure and subsequent expansion of the pores of the concrete, causing cracking, scaling, and crumbling2,8. To mitigate the deterioration

of concrete matrix and, thus, the corrosion of reinforcing steel, it is crucial to implement an adequate protection technique. According to Aguirre-Guerrero et al.9, various systems can be

employed to protect concrete structures, including improved structural design, incorporation of mineral additives, and application of coating materials. Implementing effective protection

measures reduces permeability and extends the lifespan of structures10. Coating materials can be applied to the reinforcing steel or the concrete surface. According to Taylor et al.11,12,

categorized coatings into three groups: metallic, organic, and inorganic. Epoxy, water-soluble, acrylics, vinyl resin, urethane resins, and bitumen, are commonly used to protect concrete

structures in the construction sector.13,14. The primary objective of these materials is to prevent the entry of chemical agents that could compromise the structural integrity of the

concrete elements. A. Almusallam et al.15 evaluated the adhesion strength, chloride permeability, and thermal variations of five types of coating materials, including epoxy resin. The

results showed that the epoxy material exhibited the highest adhesion strength values when applied in one layer, achieving 3.3 MPa after two weeks of application. Overall, epoxy resin

demonstrated excellent crack bridging ability, resistance to thermal variations, and low chloride permeability, outperforming polyurethane and acrylic coatings. In a similar study, Diamanti

et al.16 investigated the effect of a modified cementitious coating exposed to regular water and chlorides. Adhesion strength, water absorption, chloride diffusion, and chloride penetration

rate were assessed after two months of application. The study highlighted that this coating material significantly reduced the water content of concrete and improved its performance,

particularly with an increased polymer/cement ratio, effectively reducing steel corrosion. Epoxy coatings have also been studied for their effectiveness in protecting against sulfates

attacks17 and carbonation18,19. Freeze–thaw cycles are a common natural phenomenon that can significantly impact the durability and performance of various materials, especially in regions

with seasonal temperature fluctuations. The repeated freezing and thawing of water within the pores of materials causes the water to expand and contract, exerting substantial stresses on the

material matrix. The severity and frequency of these stresses are determined by the temperature range at which the cycles occur20. In particular, temperatures between −5 and + 15 °C have

been identified as an optimal range for studying freeze–thaw effects. This range encompasses the transition phase from freezing to thawing and represents conditions commonly encountered in

temperate climates. According to a study by Wang et al.21, approximately 60% of research papers use temperature ranges between −5 and + 15 °C in their freeze–thaw cycles. By investigating

freeze–thaw cycles within this temperature range, researchers can gain insights into the mechanisms and consequences of these cycles. They can also assess the performance and durability of

materials, and develop strategies to enhance material resilience in environments prone to such cyclic conditions22,23. The fatigue resistance and viscosity of modified bitumen coatings were

evaluated under the influence of freeze–thaw cycles.. Tengfei et al.8 subjected the material to up to 18 cycles and used Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) to analyze the chemical composition

changes. The results showed that the fatigue resistance decreased gradually after the freeze–thaw cycles, and the viscosity was excessively reduced. However, no changes were observed in the

spectral peak range of 4000–2000 cm−1. Four different coatings were used to protect concrete samples in this study. The samples were subjected to a unique accelerated aging method that

involved freeze–thaw cycles, exposure to regular water and urea, and exposure to chlorides. Concrete samples without coating protection were used as reference samples. It is important to

note that there is no published data on the results of the pull-off test and the impressed voltage technique using the proposed aging technique and materials. The objective of this research

study is to comprehensively evaluate the performance and behavior of four distinct coating materials utilized in the construction industry to safeguard concrete structures. The coatings will

be subjected to exposure to two specific contaminants, namely water and urea, which are commonly encountered in real-world scenarios. The investigation will involve applying these

protective materials to the surfaces of both reinforced and non-reinforced concrete samples. To conduct this research, a set of carefully prepared concrete specimens will be utilized. These

specimens will be divided into two groups: reinforced and non-reinforced concrete. Reinforced concrete includes additional materials such as steel bars, while non-reinforced concrete

consists solely of cement, aggregates, and water. Four distinct coating materials will be selected based on their common usage in the construction sector. These coatings may vary in their

composition, formulation, or application technique, representing a range of protective materials available in the market. By using multiple coatings, the research aims to capture a

comprehensive understanding of their individual behaviors and performance characteristics. The findings of this research will provide valuable insights into the performance and behavior of

the four coating materials when exposed to water and urea contaminants. The results can inform construction industry professionals, engineers, and material manufacturers about the most

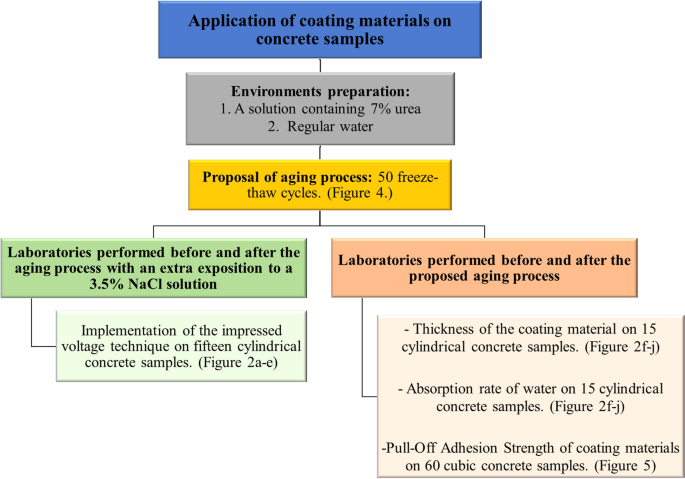

effective protective coatings to employ in specific environmental conditions. EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURE, MATERIALS, AND METHODS EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURE This research study aims to evaluate the

effectiveness of different coating materials applied to concrete surfaces exposed to various contaminants. The study will combine quantitative evidence of changes in adhesion strength,

absorption, and coating thickness. The findings will contribute to the growing research area on concrete protection in contaminated environments. Figure 1 shows the research methodology used

during this study. MATERIALS Four types of commercial coating materials commonly employed in the construction sector were used for the protection of reinforced concrete elements embedded in

contaminated soil. These coating materials include water-soluble coating (BW), solvent-based coating (BR), mineral coating (MI), and epoxy coating (EP). Additionally, control samples

without any coating material (NC) were evaluated. Table 1 describes the coating materials employed. The specifications of the concrete utilized for producing the specimens with dimensions of

(100 × 100) mm are described as per the PN-EN 206+A2:2021-08 standard24 and PN-B-06265:2018-10 standard25. Table 2 provides a detailed description of the concrete utilized in this research.

The application process for the coating materials is described as follows: * Firstly, the concrete surface was thoroughly cleaned using a regular brush to remove any dirt or debris after a

curing period of 28 days. * Before applying the MI coating, the concrete surface was properly moistened. This procedure minimizes water absorption of the mixing water by the concrete and

reduces the potential for cracking of the mineral coating26 * The application of the coating materials was carried out in accordance with the specifications provided by the manufacturer. The

protected samples were left to dry for approximately five days at room temperature of 20 ± 1 °C. * For the preparation of the, a water/cement ratio of 0.20 was used. * The epoxy material

was mixed in a weight ratio of 4:1 [A: B]. The two components were thoroughly mixed using a plastic knife for a duration of 3 min to achieve a uniform consistency. * The number of coating

layers applied varied depending on the type of coating. One layer was applied for EP and MI coatings, while two layers were applied for BR and BW coatings. In this study three types of

concrete samples were utilized. Pull-off adhesion strength tests were performed on cube-shaped specimens measuring 100 × 100 mm. Cylinders with reinforced concrete measuring 150 × 300 mm

were used for the impressed voltage technique. Additionally, cylinders measuring 100 × 50 mm were employed to assess water absorption rates. Detailed illustrations of these concrete

specimens can be found in Figs. 2 and 5. Before and after the aging process and before the exposure of the specimens to saturation, the thickness of coating materials was determined using a

PosiTector 200 coating thickness gauge. Figure 3 shows the equipment used for the thickness measurement. EXPERIMENTAL TECHNIQUES AGING PROCESS An accelerated aging test was conducted using a

Toropol K-012 frost resistance test chamber, which is commonly employed for assessing the frost resistance of building materials. The specimens were subjected to cyclical freezing in air

and thawing in water, while an electronic programmer monitored the cycles. To simulate freeze–thaw conditions in the laboratory, the test was performed at temperatures ranging between [−5]

and [+ 15] °C. Two solutions were employed to simulate contaminated environments: regular water and urea solution with a concentration of 7%. The aging process, as depicted in Fig. 4, was

applied to the samples. Furthermore, each specimen was coated with one of the four materials assessed in this research: BW, BR, MI, and EP. Additionally, a control sample without protection

(NC) was included for comparison with the protected samples. After 50 freeze–thaw cycles and a 10-day saturation period, the absorption rate, pull-off adhesion strength, and chloride

permeability of each sample were measured. The aging process used in this research is a proper procedure proposed by our research team. ADHESION STRENGTH TEST The pull-off adhesion strength

of coating applied to concrete surfaces was assessed in accordance with the ASTM D 7234-21 standard4. Cubic samples, as illustrated in Fig. 5, were used for the test. To measure the adhesion

strength, a DTH 500 DC testing machine with a maximum tensile strength of 5 kN was employed. Metallic dolls with a diameter of 50 mm and a height of 20 mm were utilized. To ensure accurate

measurement, a circular notch was drilled to define the specific surface area to be measured. Subsequently, the metallic dolls were securely attached to the concrete surface using an epoxy

material. Prior to the aging process, six pull-off tests were conducted for each coating material and environment type. The same procedure was repeated after the aging process. ABSORPTION

RATE OF WATER The ASTM C1585-20 Standard27 was followed to determine the absorption rate of water. The coating materials were applied to only one side of the sample under controlled

environmental conditions at 20 ± 2 °C and 65 ± 5% relative humidity. After curing for 7 days, the samples were dried in an environmental chamber at [+ 50] °C for 3 days. To ensure internal

moisture equilibrium, the specimens were then stored in a sealed container for 15 days. Weight measurements were taken at various intervals, including up to 6 h and once daily for 8 days.

IMPRESSED VOLTAGE TECHNIQUE To assess resistance to chloride ion permeability, the impressed voltage technique specified in the NT BUILD 356 standard28 was employed. A constant direct

current of 5 V was applied between a steel bar embedded in the concrete sample and the concrete surface. Furthermore, reinforced concrete specimens were partially immersed in a 3.0% NaCl

solution during the test duration. This test was conducted both before initiating the aging process and after seven days of completing the aging process in both coated and uncoated

reinforced concrete samples. The test concluded upon the appearance of cracks or corrosion on the surface of the steel bar. The circuit assembly utilized an external DC power supply, YIHUA

3005D [0–30 V] 5 A, and a measurement data acquisition system capable of connecting ten samples simultaneously. The schematic design is illustrated in Fig. 6. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION PULL-OFF

ADHESION STRENGTH TEST The pull-off adhesion strength results for concrete samples with and without coating material are depicted in Fig. 7. Adhesion strength values were calculated based

on the average of six pull-off readings. The results indicate that exposure to urea led to a decrease in the adhesion strength for all coatings after the aging process. Among the coatings,

EP and BW were the materials more affected, exhibiting reductions of 43.09% and 47.22%, respectively, compared to the pre-aging process results. The obtained adhesion strength values for the

EP coating, ranging between 1.36 and 2.39 MPa, align with those reported by A. Almusallam et al.15, who reported values within the range of 1.5 and 3.2 MPa. Similarly, the adhesion strength

values for the MI coating align with the findings of Flores-Colen et al.29, who obtained values higher than 1.2 MPa for mineral and cement-based coatings. On the other hand, the BR coating

exhibited the least reduction in adhesion strength after the aging process, with reductions of 0.51% for samples saturated in water and 13.63% for samples saturated in urea. This behavior

can be attributed to the low water absorption of the material resulting from the presence of hydrocarbon constituents30. In the case of EP coatings exposed to freezing temperatures, it is

important to note that epoxy materials can undergo increased rigidity and become more vulnerable to fractures when subjected to stress31. This heightened susceptibility to damage during

freeze–thaw cycles can be attributed to the sensitivity of epoxy materials to moisture. The cycling of freezing and thawing can introduce additional moisture into the epoxy, particularly if

there exist microcracks or pores within the material. The presence of moisture has the potential to weaken the mechanical properties of the epoxy, leading to degradation or failure and

ultimately resulting in a reduction in adhesion strength32. The reduction in adhesion strength observed in BW coatings can be attributed to the formation of ice crystals during the

freeze–thaw cycle. The repeated ingress of water followed by freezing can result in an increased moisture content within the material, rendering it more susceptible to damage. The expansion

and growth of these ice crystals have the potential to disrupt the integrity of the bituminous material, ultimately leading to cracking and degradation33. In contrast, solvent-based coatings

(BR) are generally less affected by freeze–thaw cycles compared to other types of materials. This is primarily due to their low water content, which significantly reduces the formation of

ice crystals. Solvent-based coatings exhibit better flexibility and toughness compared to water-based materials, allowing them to withstand the stresses and strains associated with freezing

and thawing cycles. Their increased resilience and resistance to cracking or delamination contribute to their ability to withstand freeze–thaw conditions34. Finally, even though mineral

coatings usually are more susceptible to damage from freeze–thaw cycles compared to other types of coatings due to its high porosity and the different coefficients of thermal expansion of

its materials, in our case the presence of modified polymers in the mixture improved the performance and resistance of MI coating, by incorporating polymers, such as acrylics, latexes, or

styrene-butadiene rubber (SBR), into the mix, the resulting composite exhibits improved resistance to cracking35. The polymers can accommodate minor movements and stresses within the

material, reducing the likelihood of crack formation and propagation, especially during freeze–thaw cycles or structural movement36. Additionally, it improves the adhesion to substrates and

the bond strength and the most important the polymers create a denser and more water-resistant matrix, preventing water from entering the material and reducing the potential for freeze–thaw

damage37,38. Furthermore, the concrete samples without coating materials also experienced a reduction in concrete surface resistivity as a result of contaminants infiltrating the concrete

matrix and exposure to freezing and thawing cycles. Similar results were reported by Penttala39 when concrete samples exposed to freeze–thaw cycles in saline and non-saline environments

presented surface scaling and internal damages. According to Penttala, this deterioration is primarily attributed to the requirement for higher air content in low-strength concretes.

Additionally, to categorize the results, the four types of failures resulting from the pull-off test were determined in accordance with the ASTM D 7234-2140: * i. Glue failure [A]: Failure

occurring between the epoxy used to attach the dollies to the concrete surface and the coating material. * ii. Cohesive failure [B]: Failure observed within the coating layer itself. * iii.

Adhesive failure [C]: Failure that occurs between the coating material and the concrete surface. * iv. Substrate failure [D]: Failure identified when the adhesion of the coating is stronger

than the tensile strength of the concrete surface. Figure 8 showcases some examples of the failures encountered during this study. Column 1 presents the samples before the aging process,

column 2 shows the samples after the aging process and exposure to water, and column 3 presents samples after the aging process and exposure to urea. In accordance with the failure types

defined in ASTM D 7234-2140, all types of coatings exhibit adhesive failure [C] after the aging process and exposure to urea due. This can be attributed to the high contamination levels on

the concrete surface caused by the urea components and the aging effects. Substrate failure, as depicted in (j), (k), (l), and (h), is the preferred mode of failure for coatings on

concrete40,41. However, it is important to note that the cases of substrate failure observed in Fig. 8b, c for BW cannot be considered valid due to their low adhesion values. A physical

examination was conducted on the samples to analyze the structural changes in the concrete samples protected with the various coating materials. For the MI coating, a noticeable accumulation

of calcite crystal was observed after the aging process. This phenomenon can be attributed to the crystallization of urea on the concrete surface. similar results were reported by

Ramakrishnan1 et al.42 in a study on the development of a self-repairing material able to remedy cracks and fissures in concrete using Bacillus pasteurii, Sporosarcina bacteria, and urea as

a curing method. The study revealed the formation of calcite crystals accumulations on superficial cracks, which aided in filling them and reducing the infiltration of contaminants deeper

into the concrete. Micrographs of the MI coating before and after the aging process with urea exposure are presented in Fig. 9, captured at a magnification of 10× (200 µm) under white light,

clearly displaying the accumulation of calcite crystals. However, in the case of BW and BR coatings, physical deterioration of the material was evident. Tengfei et al.8 reported that

bitumen materials exposed to freeze–thaw cycles undergo changes in the content of different chemical compounds, leading to reduced durability of the material and adversely affecting the

final adhesion strength values. WATER ABSORPTION RATE The results of water absorption rate for both coated and uncoated concrete samples before and after the aging process are illustrated in

Fig. 10. All results comply with the ASTM C1585-20 Standard27, where a linear relationship for the initial and secondary absorption was observed, with a correlation coefficient higher than

0.98. Figure 10a shows the absorption rate behavior of samples before the aging process, which aligns with a study conducted by Millan et al.43. In their research, similar coating specimens

were exposed to salt and regular water to assess their absorption properties. based on these findings, the MI coating exhibited the highest water absorption rate, followed by BR, BW, and EP

coatings. Figure 10b, c present the results of samples saturated with water and urea, respectively, and subsequently exposed to the aging process. These specimens presented a significant

reduction in the absorption rate, primarily attributed to the aging process. The absorption rate of samples exposed to urea and protected with MI coating decreased due to the accumulation of

salts in the coating surface, resulting in reduced permeability of the protected concrete. Conversely, for BR and BW coatings, a noticeable reduction in the absorption rate was observed for

samples saturated with water and urea. It is evident that the exposure to urea deteriorates the coatings, leading to an increased absorption rate of 146.73% for EP, 247.54% for BR, and

171.16% for BW compared to samples immersed in regular water. Table 3 presents the average thickness values of all coatings before and after the aging process, taking into account the

accumulation of calcite crystal on the sample surface. After exposure to water and urea, a reduction in thickness weas observed, with BW experiencing the greatest drop of 57.78% for samples

in water and 61.69% for samples in urea. Among the coatings, EP demonstrated one of the better performances, presenting reductions of 23.51% in water and 34.45% in urea. The findings of the

study reveal a compelling observation regarding the impact of aging processes on the thickness of coating materials. In particular, when subjected to both water and urea saturation, a

discernible decrease in the coating material thickness becomes apparent. This reduction in thickness can have significant consequences for the overall properties of the coating, potentially

resulting in a loss of color and compromised quality44. The aging process of coating materials involves exposure to various environmental factors, including moisture and chemical substances

like urea. When the coatings are subjected to water saturation, the moisture can gradually penetrate the material, causing it to undergo physical changes. The water may seep into the

coating, leading to a swelling effect and subsequently causing the material to expand. Over time, this expansion can result in a reduction in the thickness of the coating layer as the

material becomes more porous or undergoes partial dissolution45. IMPRESSED VOLTAGE TECHNIQUE The current intensity curves for samples before and after freeze–thaw cycles, saturated with

regular water and urea, are presented in Fig. 11. Prior to the aging process, the maximum current for samples without coating protection was 23 mA, which was 58.18% lower than the samples

saturated with regular water (55 mA). This increase indicates that the resistivity of the concrete surface has been compromised after the aging process, allowing for increased penetration of

chloride ions into the concrete matrix. On the other hand, samples without coating protection and saturated with urea exhibited a current intensity 52.36% lower than samples saturated with

water. This can be attributed to the presence of urea residues on the surface, which partially permeabilize the material and reduce the passe of chloride ions. Ramakrishnan1 et al.42. MI,

BR, and BW were the most affected materials by the freeze–thaw cycles. Before the aging process, these samples registered current values of 4.28, 2.08, and 1.98 mA, respectively. These

values increased to 26.41, 35.54, and 27.73 mA for samples saturated in regular water and 35.78, 19.72, and 33.37 mA for samples saturated in urea solution. in the case samples protected

with EP coatings, the highest current value of 18.93 mA was obtained in the samples exposed to urea, showing an increase of 235.10% before freeze–thaw cycles and 297.57% for samples

saturated in water. These results align with previous findings by with Aguirre et al.46, where the highest current value for samples with epoxy coating was reported as 8 mA. Furthermore, it

can be observed that, for all samples, the use of coating materials extended the appearance of corrosion products, thus protecting the concrete matrix in a chloride ion environment. Figure

12 presents EP, BR, and BW concrete samples after the aging process, revealing visible physical damage in the coating materials. It is important to note that MI coating remained intact and

undamaged throughout the aging process, regardless of exposure to water and urea. Similarly, EP samples exposed to water did not present any physical damage, effectively hindering the

diffusion of chlorides into the concrete. However, EP samples exposed to urea, as well as BR, and BW samples exposed to water and urea, showed signs of physical damage. Among them, BW

samples saturated with urea were the most adversely affected after the aging process. The implementation of the impressed voltage technique in this study provides supplementary evidence that

reinforces the relationship between absorption rate and coating degradation. The observed increase in current intensity, for all samples in both water and urea, and the accelerated

appearance of corrosion products indicate a more rapid corrosion process when the absorption rate is higher. This conclusion is further reinforced by the substantial reduction in the time

required for corrosion products to manifest. Specifically, the duration decreased from 386 to 30 h for EP, from 107 to 12 h for MI, and corrosion appearance was evident for BR and BW

coatings after 77 h of exposure to the urea solution. Figure 13 presents the coated and uncoated reinforced concrete samples after the aging process and corrosion test. None of the specimens

presented cracks on the concrete surface during the corrosion test, indicating that all laboratories were concluded once corrosion products became visible. After 22 days of testing, BW and

BR samples did not present any corrosion on the concrete surface. In this case, the test was finalized, analyzing the materials' resistance to chloride ions. It is important to

highlight that EP samples exposed to regular water did not present any physical damage before the impressed voltage technique. However, the presence of chlorides and the current that passes

through the concrete deteriorated the coating material, leading to its fracture and physical damage. CONCLUSIONS The pull-off adhesion strength of the different coatings presented a

reduction after the freeze–thaw cycles. However, the presence of urea during the aging process led to a significant decrease in adhesion values, particularly for EP and BW coatings. The

thickness measurements for these materials showed reductions of 34.46% and 61.69%, respectively, which likely contributed to the decrease in adhesion strength along with surface

contamination by urea crystallization. In contrast, BR coating demonstrated a reduction of 13.10% in thickness and 13.63% in adhesion strength when exposed to urea solution, indicating it

superior performance in terms of adhesion and thickness measurements after the aging process. The results of absorption rate analysis revealed that MI, EP, and BW coatings, when exposed to

regular water and urea, as well as BR coating exposed to regular water, exhibited a decrease in water absorption rate compared to samples that were not exposed to freeze–thaw cycles.

Although these results were unexpected considering the reductions observed in adhesion strength and thickness, the decrease can be attributed to the accumulation of crystals on the coating

surface. Moreover, the physical examination analysis indicating the formation of calcite crystals on the concrete surface when cured in the urea solution. These crystals effectively filled

superficial cracks, thereby reducing the material's permeability. The impressed voltage technique demonstrated an increase in current intensity after the freeze–thaw cycles.

Furthermore, samples saturated with the urea solution exhibited higher current values compared to those saturated with regular water. However, regardless of the saturation solution, all

types of coatings extended the appearance of corrosion products, with BR and BW coatings performing the best in this regard. The findings of this study provide valuable insights into the

behavior of epoxy-based coatings under aging conditions, particularly in relation to exposure to urea. The results clearly indicate that the adhesion strength of the epoxy coating is

significantly reduced after undergoing the aging process, with urea exposure being a particularly influential factor in this degradation. The results demonstrate a direct correlation between

the increase in the current intensity and the weakening of bonds between the coating and the substrate in the case of exposition to urea solution. Overall, the findings indicate a decrease

in adhesion strength and an increase in current intensity for all samples when exposed to regular water and urea. However, it is worth noting that there is no clear evidence of an increase

in the absorption rate in the case or regular water. On the contrary, the results suggest that the absorption rate actually decreases with the aging process and water exposure. Further

investigation is necessary to fully understand and elucidate this behavior. A noticeable reduction in coating material thickness after the aging process, whether through water or urea

saturation, has implications for the visual appearance and protective qualities of the coating. To mitigate these issues, further research and development may be necessary to enhance the

durability and resistance of coating materials against aging processes. The formulation of coatings could be optimized to withstand prolonged exposure to water, urea, and other environmental

stressors. Based on the findings related to adhesion strength and absorption rate, the epoxy-based (EP) coating demonstrates its superiority as the optimal choice for providing effective

protection to concrete structures. The results of this study provide substantial evidence supporting the suitability of EP coatings in safeguarding against deterioration and corrosion

processes. The consistently high adhesion strength exhibited by the EP coating, even after the aging process, suggests its ability to maintain a robust bond with the substrate. This strong

adhesion is crucial for ensuring long-term durability and protection, as it minimizes the potential for coating detachment or delamination. The ability of the EP coating to withstand the

adverse effects of aging, including exposure to urea and regular water, further validates its suitability for concrete protection. RESEARCH LIMITATIONS > This paper was limited to English

articles, which excludes > literature published in other languages and is also limited to > academic publications. Moreover, it does not consider the results > from industrial

practice. DATA AVAILABILITY All data generated or analyzed during this study that support the findings are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request and with the

permission of all authors. REFERENCES * Adewuyi, A. Strength and durability assessment of concrete substructure in organic and hydrocarbon polluted soil. _Int. J. Mod. Res. Eng. Technol.

(IJMRET)_ 2, 34–42 (2017). Google Scholar * Safiuddin, M. & Hearn, N. Comparison of ASTM saturation techniques for measuring the permeable porosity of concrete. _Cem. Concr. Res._ 35,

1008–1013. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconres.2004.09.017 (2005). Article CAS Google Scholar * Chen, Y. _et al._ Self-healing coatings for steel-reinforced concrete. _ACS Sustain. Chem.

Eng._ 5, 3955–3962. https://doi.org/10.1021/acssuschemeng.6b03142 (2017). Article CAS Google Scholar * Mirsal, I.A. _Soil Pollution. Origin, Monitoring and Remediation_. 2nd Ed. (2004). *

Millán Ramírez, G. P., Byliński, H. & Niedostatkiewicz, M. Deterioration and protection of concrete elements embedded in contaminated soil: A review. _Materials_ 14, 3253.

https://doi.org/10.3390/ma14123253 (2021). Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Jedidi, M. & Benjeddou, O. Chemical causes of concrete degradation. _MOJ Civ.

Eng._ 4, 40–46. https://doi.org/10.15406/mojce.2018.04.00095 (2018). Article Google Scholar * Portland Cement Association. _Types and Causes of Concrete Deterioration, Portland Cement

Association—Concrete Information_. 1–16 (PCA R & D Se, 2002). * Nian, T. _et al._ The effect of freeze–thaw cycles on durability properties of SBS-modified bitumen. _Constr. Build

Mater._ 187, 77–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.07.171 (2018). Article CAS Google Scholar * Aguirre-Guerrero, A.M. & de Gutiérrez, R.M. _Assessment of Corrosion

Protection Methods for Reinforced Concrete_. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-102181-1.00013-7 (2018). * Cyr, M. _Influence of Supplementary Cementitious Materials (SCMs) on Concrete

Durability_. https://doi.org/10.1533/9780857098993.2.153 (2013). * Taylor, S.R. _Coatings for Corrosion Protection: Inorganic, Encyclopedia of Materials: Science and Technology_. 1263–1269.

https://doi.org/10.1016/b0-08-043152-6/00238-2 (2001). * Taylor, S.R. _Coatings for corrosion protection: Organic_ In _Encyclopedia of Materials: Science and Technology_. 1274–1279.

(Elsevier, 2001). https://doi.org/10.1016/B0-08-043152-6/00240-0. * Tittarelli, F. & Moriconi, G. The effect of silane-based hydrophobic admixture on corrosion of reinforcing steel in

concrete. _Cem. Concr. Res._ 38, 1354–1357. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconres.2008.06.009 (2008). Article CAS Google Scholar * Vaidya, S. & Allouche, E. N. Electrokinetically

deposited coating for increasing the service life of partially deteriorated concrete sewers. _Constr. Build. Mater._ 24, 2164–2170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2010.04.042 (2010).

Article Google Scholar * Almusallam, A., Khan, F. M. & Maslehuddin, M. Performance of concrete coatings under varying exposure conditions. _Mater. Struct. Mater Construct._ 35,

487–494. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02483136 (2002). Article CAS Google Scholar * Diamanti, M. V. _et al._ Effect of polymer modified cementitious coatings on water and chloride

permeability in concrete. _Constr. Build. Mater._ 49, 720–728. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2013.08.050 (2013). Article CAS Google Scholar * Suleiman, A. R., Soliman, A. M. &

Nehdi, M. L. Effect of surface treatment on durability of concrete exposed to physical sulfate attack. _Constr. Build. Mater._ 73, 674–681. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2014.10.006

(2014). Article Google Scholar * Park, D. C. Carbonation of concrete in relation to CO2 permeability and degradation of coatings. _Constr. Build. Mater._ 22, 2260–2268.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2007.07.032 (2008). Article Google Scholar * Ahmed, N. M., Mohamed, M. G., Tammam, R. H. & Mabrouk, M. R. Performance of coatings containing

treated silica fume in the corrosion protection of reinforced concrete. _Pigm. Resin Technol._ 47, 350–359. https://doi.org/10.1108/PRT-08-2017-0076 (2018). Article CAS Google Scholar *

Pilehvar, S. _et al._ Effect of freeze-thaw cycles on the mechanical behavior of geopolymer concrete and Portland cement concrete containing micro-encapsulated phase change materials.

_Constr. Build. Mater._ 200, 94–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.12.057 (2019). Article Google Scholar * Wang, R., Zhang, Q. & Li, Y. Deterioration of concrete under the

coupling effects of freeze–thaw cycles and other actions: A review. _Constr Build Mater._ 319, 126045. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.126045 (2022). Article CAS Google Scholar

* Deschenes, R. A., Giannini, E. R., Drimalas, T., Fournier, B. & Hale, M. Effects of moisture, temperature, and freezing and thawing on alkali-silica reaction. _ACI Mater. J._ 115,

575–584. https://doi.org/10.14359/5170219 (2018). Article Google Scholar * Wang, R., Hu, Z., Li, Y., Wang, K. & Zhang, H. Review on the deterioration and approaches to enhance the

durability of concrete in the freeze–thaw environment. _Constr. Build. Mater._ 321, 126371. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.126371 (2022). Article CAS Google Scholar * PN-EN

206 + A2: 2021-08. _Beton-Wymagania__, __właściwości użytkowe__, __produkcja i zgodność, Polski Komitet Normalizacyjny_. https://sklep.pkn.pl/pn-en-206-a2-2021-08e.html. Accessed 22 May 2022

(2021). * PN-EN 206+A1:2016-12. _Beton-Wymagania__, __właściwości__, __produkcja i zgodność—Krajowe uzupełnienie__, __Polski Komitet Normalizacyjny_.

https://sklep.pkn.pl/pn-b-06265-2018-10p.html Accessed 22 May 2022 (2018). * Aguirre-Guerrero, A. M., Robayo-Salazar, R. A. & de Gutiérrez, R. M. A novel geopolymer application: Coatings

to protect reinforced concrete against corrosion. _Appl. Clay Sci._ 135, 437–446. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clay.2016.10.029 (2017). Article CAS Google Scholar * ASTM C1585-20. _Standard

Test Method for Measurement of Rate of Absorption of Water by Hydraulic-Cement Concretes_. Vol. 3 (ASTM International, 2020). * NT BUILD 356. _Concrete, Repairing Materials and Protective

Coating: Embedded Steel Method, Chloride Permeability_, _North Test Method_. 1–3 (1989). * Flores-Colen, I., Brito, J. & Branco, F. In situ adherence evaluation of coating materials.

_Exp. Tech._ https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-1567.2008.00372.x (2009). Article Google Scholar * Anderson, A. P. & Wright, K. A. Permeability and absorption properties of bituminous

coatings. _Ind. Eng. Chem._ 33, 991–995. https://doi.org/10.1021/ie50380a008 (1941). Article CAS Google Scholar * Evans, D. _R. Appleton Laboratory, Investigation of Fracture Properties

of Epoxy at Low Temperatures._ * Allred, R.E. & Roylance, D.K. _Transverse Moisture Sensitivity of Aramid/Epoxy Composites_. * Teltayev, B. B., Rossi, C. O., Izmailova, G. G. &

Amirbayev, E. D. Effect of freeze–thaw cycles on mechanical characteristics of bitumens and stone mastic asphalts. _Appl. Sci. (Switzerland)_ https://doi.org/10.3390/app9030458 (2019).

Article Google Scholar * Stojanović, I., Cindrić, I., Turkalj, L., Kurtela, M. & Rakela-Ristevski, D. Durability and corrosion properties of waterborne coating systems on mild steel

dried under atmospheric conditions and by infrared radiation. _Materials._ https://doi.org/10.3390/ma15228001 (2022). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Bothra, S.R. &

Ghugal, Y.M. _Polymer-Modified Concrete: Review_. http://www.ijret.org. * Zhang, X. _et al._ Polymer-modified cement mortars: Their enhanced properties, applications, prospects, and

challenges. _Constr. Build Mater._ 299, 124290. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CONBUILDMAT.2021.124290 (2021). Article CAS Google Scholar * Łukowski, P. & Debska, D. Effect of polymer

addition on performance of portland cement mortar exposed to sulphate attack. _Materials._ https://doi.org/10.3390/ma13010071 (2020). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar *

Abdulrahman, P. I. & Bzeni, D. K. Bond strength evaluation of polymer modified cement mortar incorporated with polypropylene fibers. _Case Stud. Construct. Mater._

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cscm.2022.e01387 (2022). Article Google Scholar * Penttala, V. Surface and internal deterioration of concrete due to saline and non-saline freeze–thaw loads.

_Cem. Concr. Res._ 36, 921–928. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconres.2005.10.007 (2006). Article CAS Google Scholar * ASTM D7234-21. _Standard Test Method for Pull-Off Adhesion Strength of

Coatings on Concrete Using Portable Pull-Off Adhesion Testers_. Vol. 8 (ASTM International, 2021). * Khan, F. M. _Performance Evaluation of Concrete Coatings_ (King Fahd University of

Petroleum & Minerlas, 2000). Google Scholar * Ramakrishnan, V., Ramesh, K. P. & Bang, S. S. Bacterial concrete. _Smart Mater._ 4234, 168–176. https://doi.org/10.1117/12.424404

(2001). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Millán Ramírez, G. P., Byliński, H. & Niedostatkiewicz, M. Mechanical and physical assessment of epoxy, mineral, solvent-based, and

water-soluble coating materials. _Sci. Rep._ 12, 13647. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-18022-0 (2022). Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Wu, G. & Yu, D.

Preparation and characterization of a new low infrared-emissivity coating based on modified aluminum. _Prog. Org. Coat._ 76, 107–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.porgcoat.2012.08.018 (2013).

Article CAS Google Scholar * Han, D. H. _et al._ Effects of aging on the thickness of a homogeneous film fabricated using a spin coating process. _J. Coat. Technol. Res._ 18, 641–647.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11998-020-00429-x (2021). Article CAS Google Scholar * Aguirre-Guerrero, A. M. & Mejía de Gutiérrez, R. Alkali-activated protective coatings for reinforced

concrete exposed to chlorides. _Constr. Build. Mater._ 268, 121098. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.121098 (2021). Article CAS Google Scholar Download references

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This paper did not receive specific grants from public, commercial, or not-for-profit funding agencies. AUTHOR INFORMATION AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Department of

Engineering Structures, Faculty of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Gdansk University of Technology, 11/12 Narutowicza Street, 80-226, Gdańsk, Poland Ginneth Patricia Millán Ramírez,

Hubert Byliński & Maciej Niedostatkiewicz Authors * Ginneth Patricia Millán Ramírez View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Hubert Byliński

View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Maciej Niedostatkiewicz View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google

Scholar CONTRIBUTIONS G.P.M.R: Conceptualization, formal analysis, investigation, original draft, methodology, data curation, visualization. H.B: Validation, critical revision of the

article, and final approval of the version to be published. M.N: Validation, supervised the research, critical revision of the article, and final approval of the version to be published.

CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to Ginneth Patricia Millán Ramírez. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS The authors declare no competing interests. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

PUBLISHER'S NOTE Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS OPEN ACCESS This article

is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give

appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in

this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's

Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Millán Ramírez, G.P., Byliński, H. &

Niedostatkiewicz, M. Effectiveness of various types of coating materials applied in reinforced concrete exposed to freeze–thaw cycles and chlorides. _Sci Rep_ 13, 12977 (2023).

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-40203-8 Download citation * Received: 23 April 2023 * Accepted: 07 August 2023 * Published: 10 August 2023 * DOI:

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-40203-8 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not

currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative