Play all audios:

ABSTRACT Parents of very low birth weight (VLBW) infants in a neonatal intensive care unit experienced additional stress during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic due to the related restrictions in

hospital visiting policies. Our study aimed to compare parents' burdens before and during the pandemic. This survey included 121 parents of 76 VLBW infants in two European Level IV

perinatal centers before and during the pandemic. We performed standardized parent questionnaires with mothers and fathers separately to evaluate their emotional stress and well-being. The

pandemic worsened the emotional well-being of parents of VLBW infants, particularly of mothers. During the pandemic, mothers reported significantly higher state anxiety levels (48.9 vs.

42.9, _p_ = 0.026) and hampered bonding with the child (6.3 vs. 5.2, 0 = 0.003) than before. In addition, mothers felt more personally restricted than fathers (6.1 vs. 5.2, _p_ = 0.003).

Fathers experienced lower levels of stress than mothers; they were equally burdened before and during the pandemic. Restrictions in visiting policies for families of VLBW infants during the

SARS-CoV-2 pandemic have a significant negative impact on parental stress and should therefore be applied cautiously. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS A GLOBAL PERSPECTIVE ON PARENTAL

STRESS IN THE NEONATAL INTENSIVE CARE UNIT: A META-ANALYTIC STUDY Article 08 September 2020 PARENTAL PROTECTIVE FACTORS AND STRESS IN NICU MOTHERS AND FATHERS Article 18 December 2020 INFANT

DELIVERY AND MATERNAL STRESS DURING THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC: A COMPARISON OF THE WELL-BABY VERSUS NEONATAL INTENSIVE CARE ENVIRONMENTS Article 13 May 2021 INTRODUCTION Parents of very low

birth weight (VLBW) infants face numerous burdens1,2,3. Feelings of guilt and being overwhelmed by the unexpected end of the pregnancy, the sudden concern for a prematurely born vulnerable

child who may suffer health and developmental problems, and own health issues can cause considerable stress. It can be challenging for parents to develop a close bond with their premature

infant. Different studies showed that parental stress might have negative long-term consequences on the parent–child interaction and the child's development4, 5. Several studies

examined the relationship between visitation policies6, quality of visits7, the opportunity for rooming-in8, and frequency of parental visits9 and overall well-being, parental child bonding

and breastfeeding. When interviewed, parents unanimously conclude that flexible visitation times and proximity to the child influence their well-being7. A Finnish study showed an association

between infrequent visits by parents and later behavioral problems in their prematurely born children9. Regular parental visits, proximity, and involvement in the care of the premature

infant in the NICU may promote parental bonding and infant development. Parent-centered care concepts with the possibility of parental presence without restrictions, skin-to-skin care, and

involvement of parents in their child's care are employed to address these difficulties in modern neonatal intensive care units (NICUs). The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic required significant

social restrictions, including more stringent hospital visiting policies at the beginning of the pandemic. In many NICUs, only one parent was allowed to visit the newborn. Moreover, parents

reported significant insecurity and anxiety concerning even more restrictive measures10,11,12. We had the unique opportunity to survey parents of VLBW infants before and during the pandemic

and compare their burdens regarding anxiety, parenting stress, and social support. METHODS STUDY DESIGN We performed this survey in the NICUs of the Level-IV perinatal center of the

University Children's Hospital, Medical University Vienna, Austria, and the Level-IV University Children’s Hospital, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Germany. Between

February and May 2021, parents of VLBW infants (gestational age under 32 weeks) took part in this survey after approval of the local ethical review committees (Ethics Committee of the

Medical University of Vienna, Austria, Nr.:1504/2020; and Ethics Committee of the Medical Association Hamburg, Germany, Nr.: PV7403). We reported the survey results according to the AAPOR

Reporting guidelines. The historical control group consisted of families of preterm infants who took part in a previous study about the occupational balance in parents of premature infants

performed during 2018 and 2019 at the perinatal center of the Medical University Vienna using the same questionnaires (Ethics 1891/2015)13. VISITING RESTRICTIONS The visiting restrictions

implemented during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic stipulated that only one parent had access to their hospitalized child at a time in both centers, and other visitors were not allowed. Neither at

the Medical University in Vienna nor at the University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf were any time restrictions regarding parents' visits before the pandemic. SURVEY INSTRUMENTS The

study included three standardized parent questionnaires and an anamnesis for parents' characteristics. Mothers and fathers were invited to fill in the questionnaires separately. Parents

who were unable to read German were excluded because only questionnaires in German were available. Questionnaires were administered to parents toward the end of their stay, and they were

asked to complete them regarding their most stressful time. We explicitly instructed parents to reflect on the most stressful period during their infant's hospitalization, rather than

referring to any other events in their lives. The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory Form (STAI)14 consists of 40 self-report items measuring the presence and severity of current symptoms of

parents’ anxiety and a general tendency toward anxiety. The STAI clearly distinguishes between the “State Anxiety” Scale, defined as the current state of anxiety, asking how parents are

feeling “right now” (e.g., “I am calm” or “I feel rested”) on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from “not at all” to “very much so”. The “Trait Anxiety” Scale assesses the frequency of feelings

of anxiety “in general” from “almost never” to “almost always” (e.g., "I feel like crying" or "I am content"). Higher scores indicate greater anxiety; a score of 20

corresponds to the absence and a score of 80 to the maximum intensity of a feeling of anxiety. The Social Support Questionnaire (F-SozU by Sommer & Fydrich, 1989, 1991)15: The German

self-report questionnaire is a 14-item short form and measures subjectively perceived or anticipated support from the social environment (e.g., “I have people who share my joys and sorrows

with me.”). Parents answer the 14 items on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from "strongly disagree" to "strongly agree." The higher the scale value, the greater the

perceived support from the social environment. Scores (percentile rank) above 25 are defined as unremarkable. Parenting Stress Index (PSI): Parenting stress was assessed using the Parenting

Stress Index, Third Edition16, is designed to evaluate the magnitude of stress in the parent–child system. Stress in the parenting domain results from impaired parental functioning, which

reduces the resources available to parents in coping with parenting and demands. We used four of seven sources of parental stress, Parental Attachment (e.g., “It is sometimes difficult to

figure out my child's needs”), Social Isolation (e.g., “I often feel on my own”), Health (e.g., “Over the last six months I have been very physically exhausted”), and Personal

Limitation (e.g., "I sometimes feel restricted by the responsibilities of being a mother/father"). Questions were answered by parents on a Likert scale from "strongly

agree" to "strongly disagree" in terms of current life stress. Stanine values were then calculated with a range between one and nine. A value of seven and greater indicates a

high stress level in this section. DATA ANALYSIS Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and range. Discrete data were compared between groups with the

Fishers' exact, and the Pearson’s Chi-square tests. A two-tailed t-test was used to compare continuous variables before and after the intervention. In addition, we calculated linear

regression models to analyze the impact of the predictor variables survey time point, CRIB II17, parent gender, parent marital status to analyze the parent's Social Support, Parenting

Stress Index (including the subcategories bonding, personal restrictions, social integration, and health), and the STAI State and Trait Anxiety. P values less than 0.05 were considered

significant. Statistical analyses were performed using R 4.1.2 (R Core Team, Vienna, Austria). STATEMENT OF ETHICS This is a study was approved by the local ethics committee (ethic number:

1504/2020) of the Medical University of Vienna. PATIENT CONSENT STATEMENT Informed consent was obtained by each participants participating in this study. RESULTS INFANT CHARACTERISTICS

Overall, parents of 76 VLBW infants were included in the analysis. Thirty VLBW infants with a mean ± SD (range) gestational age of 27.1 ± 2 (23.3–31.4) weeks and a birthweight of 934 ± 295

(500–1490)g were examined in Vienna before the pandemic, and a total of 46 VLBWs with a mean ± SD gestational age of 26.8 ± 2.5 (22.9–31.7) weeks and a birthweight of 893 ± 309 (390–1500)g

during the pandemic (35 in Vienna and 11 in Hamburg). Infant characteristics between the centers were similar (supplementary Table 1), therefore further analyses will refer to the

aggregation of both groups. Infant characteristics before and during the pandemic are presented in Table 1 showing no significant differences within descriptive characteristics and clinical

outcomes. PARENT CHARACTERISTICS We surveyed 121 parents of VLBW infants, 40 parents from Vienna before the pandemic and 81 parents during the pandemic (61 from Vienna, 20 from Hamburg).

Table 2 shows detailed characteristics of the participating parents. Out of the total number of children, both parents responded in the case of 45 children. Among these 45 children, 10 pairs

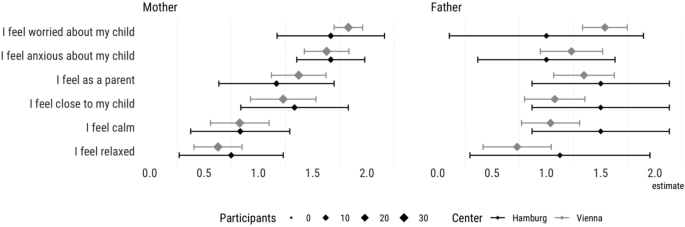

of parents completed the questionnaire before the onset of the pandemic, while 35 pairs of parents completed it during the pandemic. Figure 1 provides descriptive information about the

actual feelings of mothers and fathers when the questionnaires were filled in. Parents’ characteristics were similar before and during the pandemic and between centers (see supplementary

Table 2). PARENTS’ BURDEN Survey results of parents' burden are presented before and during the pandemic and shown separately for mothers and fathers (Fig. 2, supplementary Table 3).

ANXIETY (A) According to the STAI State Questionnaire, state anxiety was significantly higher among mothers during the pandemic (48.9 ± 11.0) than before (42.9 ± 10.1, _p_ = 0.026). It was

additionally more pronounced among mothers than among fathers both before (42.9 ± 10.1 vs. 36.3 ± 6.0, _p_ = 0.031) and during (48.93 ± 11.0 vs. 39.8 ± 9.6, _p_ < 0.001) the pandemic

(Fig. 2-A; supplementary Table 3). Linear regression models also showed that the pandemic significantly increased state anxiety, confirming that fathers reported lower anxiety scores on

average than mothers (Fig. 3). On the other hand, trait anxiety did not differ between fathers and mothers according to the STAI trait questionnaire (Fig. 2-A). Furthermore, the linear

regression model showed no impact of the respective predictors (survey time point, CRIB II, sex of the parent gender, parent marital status) analyzed on the trait anxiety of the parents

(Fig. 3). PERCEIVED SOCIAL SUPPORT (B) Mothers and fathers reported similar perceived social support before and during the pandemic (Fig. 2-B, supplementary Table 3). This result was further

confirmed by the linear regression model (Fig. 3). PARENTING STRESS (C) For mothers, bonding was more challenging during the pandemic than before (6.3 ± 1.8 vs. 4.9 ± 1.8, _p_ = 0.003)

(Fig. 2-C, supplementary Table 3). In addition, the linear regression model confirmed that the pandemic negatively influenced bonding, whereas the other tested predictors were not

statistically significant (Fig. 3). Mothers felt more personally restricted during the pandemic than fathers (6.1 ± 2.0 vs. 5.2 ± 2.0, _p_ = 0.003) (Fig. 2-C, supplementary Table 3). The

linear regression model confirmed that the pandemic significantly increased feelings of personal restriction, with fathers feeling less restricted than mothers (Fig. 3). In addition, mothers

rated health burdens higher during the pandemic than fathers (6.6 ± 1.6 vs. 5.3 ± 1.5, _p_ = 0.007). In general, the linear regression model also revealed that greater severity of illness

in children, indicated by a higher CRIB II score, led to lower ratings of social integration and a lower health burden rating (Fig. 3). DISCUSSION This survey at two Level IV perinatal

centers in German-speaking countries shows that the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic significantly impacted the burden on parents of high-risk preterm infants. Parents perceived more anxiety, and

suffered from personal restrictions and impaired bonding with their children following visiting restrictions during the pandemic. In addition, we detected gender differences among parents,

with fathers reporting less interference for each aspect. Premature neonates require specialized care in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) due to their unique medical needs. While

medical interventions play a crucial role in their survival and well-being, parental support and presence have emerged as essential components of their care. Parental involvement for

premature neonates in the NICU has a significant impact on their long-term development due to several crucial aspects of parent infant interaction: (1) emotional Bonding: Parental presence

allows premature neonates to develop a secure attachment, facilitating emotional bonding and fostering a sense of security and trust18, 19; (2) neurodevelopment: Parental support, including

skin-to-skin contact (kangaroo care), promotes neurodevelopmental outcomes by reducing stress, improving physiological stability, and enhancing brain development20; (3) breastfeeding:

Parental presence encourages breastfeeding, which provides essential nutrients, immune factors, and promotes infant growth and development; (4) Long-term Outcomes: Numerous studies have

demonstrated that parental support and presence in the NICU lead to improved cognitive, social, and emotional outcomes in premature neonates during infancy and later in life20, 21. Our

results show that additional negative impact on parental stress resulted from visitation restrictions during the pandemic. In detail, we observed a significant increase in self-reported

anxiety in mothers of preterm infants before and during the pandemic, consistent with the literature12,22, 23, reporting increased maternal stress during the pandemic. Emotionally distressed

parents find it more challenging to fulfill their roles in caring for, supporting, and raising their infant24. This is of particular relevance as parental support is extremely important for

children hospitalized in an intensive care unit21,25, 26. It has been shown that hospitalized infants thrive best when they are consistently cared for by their parents in a

family-integrated setting25. Parental presence has been found to be associated with benefits for preterm infants, including more stable physiological responses, improved oral feeding, and

reduced length of stay25, 26. The more stressed and burdened parents are, the less well they can be supportive for their children. Therefore, the additional stress caused by the pandemic may

have a significant impact on parents but also on their premature infant. We also found less bonding in mothers with their preterm infant during the pandemic, while the father-child

attachment was mainly unaffected. Parent-infant bonding plays a crucial role in fostering a positive parent-infant relationship and promoting long-term infant health27, 28. However, the

experience of preterm birth can disrupt or delay this bonding process29. Studies have shown that bonding is influenced by factors such as physical proximity between parent and infant, the

emotional state of the mother, and the infant's ability to communicate27. Unfortunately, these aspects can be compromised in the neonatal intensive care setting. Our results show that

visitation restrictions in the context of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic were an additional disruptive factor for mother–child bonding. Problems regarding attachment in mother-preterm dyads during

the pandemic have been reported before22,23,24,30. Knowing that bonding in the first few weeks of a child's life is of great importance, these infants might suffer from long-term

consequences in their emotional but also neurological development. When comparing mothers and fathers, findings indicate a significant difference as mothers experienced health stress, loss

of energy, and psychological and physical exhaustion much more than fathers. Our results suggest that the physical environment of the NICU becomes an even more stressful setting during the

pandemic, associated with health issues, personal restrictions, and lower levels of attachment, especially among mothers. This is in line with the study of Hagen et al.31 demonstrating that

mothers experience more stress when being with the baby in the NICU without the father. We interpret this finding in our study as a consequence of the mother spending more time in the ward

and the missing supporting role of the father or other relatives. During the pandemic, parents were not allowed to stay in the NICU together at the same time. These restrictions allowed

closeness between the child and only one of the two parents and hampered emotional moments and mutual support as a couple under challenging situations. The only exception was the first week

after birth, when mothers were still admitted to the postnatal ward. Thus, it can be derived from the results of our study, that the supportive role of fathers and other family members for

both infants’ care and mothers’ support is important, even in times of a pandemic. It will be essential to further develop parent-focused interventions during a NICU stay also for times of

pandemic situations, mainly to improve attachment quality and health outcomes and reduce personal limitations, stress, and anxiety25,26,32. Erdei and Liu33 published guidelines for

supporting family-well-being in the NICU during a pandemic. Kostenzer et al.34 underlined the importance of parental presence for infants’ well-being in a NICU setting and published a call

for “zero separation”. There are some strengths of this study that merit special attention. This is one of few studies with a historical control group focusing on parents' experiences

with infants in need of intensive care two years before the pandemic. In addition, we were able to comprehensively describe mothers' and fathers' experiences of stress in the NICU.

In most previous studies, parents were interviewed together, or the number of fathers who participated in the study was low. In the current study, we were able to interview both, father and

mother, separately, to highlight the differences between the parents. We also paid particular attention to the selection of questionnaires to ensure well-validated and internationally

recognized questionnaires standardized on a large sample, thus avoiding self-designed and non-comparable questionnaires. There are some limitations of this study that need to be considered.

Conducting surveys in only two perinatal hospitals carries the risk of selection bias and may have affected the representativeness of participants. Only parents who were able to read and

understand German could participate in the study. Probably we missed parents with most burden due to multiple risk factors (migration, social integration, financial problems). Nevertheless,

we found that the characteristics of both high-risk infants and parents did not differ between Vienna and Hamburg, so we assume that study subjects are very likely to have been comparable

between the two centers also before the pandemic. CONCLUSIONS This study showed a substantial negative impact of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic on multiple aspects of burden and stress among

parents of VLBW infants. Potential negative long-term consequences for parents and infants following the restrictions during the pandemic are not yet known. Caregivers should be aware that

families of VLBW infants are a vulnerable population experiencing multiple traumas and stress during their time in the NICU and that additional stress factors such as visiting restrictions

increase this burden and stress. In view of the future, the elaboration of developmental care guidelines in times of pandemics is warranted, facilitating the presence of both parents in the

NICU and communication between parents as important aspects for copying with a very stressful event such as a preterm birth. Further studies should focus on the potential adverse long-term

consequences of this stressful experience on infants and families. DATA AVAILABILITY All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article (and its

supplementary information files). The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. REFERENCES *

Roque, A. T. F., Lasiuk, G. C., Radünz, V. & Hegadoren, K. Scoping review of the mental health of parents of infants in the NICU. _J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal. Nurs._ 46(4), 576–587

(2017). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Pados, B. F. & Hess, F. Systematic review of the effects of skin-to-skin care on short-term physiologic stress outcomes in preterm infants in

the neonatal intensive care unit. _Adv. Neonatal Care_ 20(1), 48–58 (2020). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Al Maghaireh DaF, Abdullah KL, Chan CM, Piaw CY, Al Kawafha MM. Systematic

review of qualitative studies exploring parental experiences in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. _J. Clin. Nurs._ 2016;25(19–20):2745–2756. * Ionio, C. _et al._ Mothers and fathers in NICU:

The impact of preterm birth on parental distress. _Eur J Psychol._ 12(4), 604–621 (2016). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Turpin, H. _et al._ The interplay between

prematurity, maternal stress and children’s intelligence quotient at age 11: A longitudinal study. _Sci. Rep._ 9(1), 450 (2019). Article ADS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar *

Flacking, R., Ewald, U., Nyqvist, K. H. & Starrin, B. Trustful bonds: a key to “becoming a mother” and to reciprocal breastfeeding. Stories of mothers of very preterm infants at a

neonatal unit. _Soc. Sci. Med._ 62(1), 70–80 (2006). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Franck, L. S., Cox, S., Allen, A. & Winter, I. Measuring neonatal intensive care unit-related

parental stress. _J. Adv. Nurs._ 49(6), 608–615 (2005). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Theo, L. O. & Drake, E. Rooming-in: Creating a better experience. _J. Perinat. Educ._ 26(2),

79–84 (2017). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Latva, R., Lehtonen, L., Salmelin, R. K. & Tamminen, T. Visiting less than every day: a marker for later behavioral

problems in Finnish preterm infants. _Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med._ 158(12), 1153–1157 (2004). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Verweij EJ, M’hamdi HI, Steegers E, Reiss IKM, Schoenmakers

S. Collateral damage of the covid-19 pandemic: a Dutch perinatal perspective. _BMJ (Clin. Res. Ed.)_ 2020;369. * Murray, P. D. & Swanson, J. R. Visitation restrictions: is it right and

how do we support families in the NICU during COVID-19?. _J. Perinatol._ 40(10), 1576–1581 (2020). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * van Veenendaal, N. R., Deierl, A.,

Bacchini, F., O’Brien, K. & Franck, L. S. Supporting parents as essential care partners in neonatal units during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. _Acta paediatrica (Oslo, Norway: 1992)_ 110(7),

2008–2022 (2021). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Dür, M. _et al._ Associations between parental occupational balance, subjective health, and clinical characteristics of VLBW infants.

_Front Pediatr._ 10, 816221 (2022). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Laux L, Glanzmann PG, Schaffner P, Spielberger CD. _Das State-Trait-Angstinventar (STAI) : theoretische

Grundlagen und Handanweisung._ Beltz; 1981. * Sommer G, Fydrich T. _Soziale Unterstützung: Diagnostik, Konzepte, F-SOZU._ Tübingen: Deutsche Gesellschaft für Verhaltenstherapie; 1989. *

Abidin, R. R. _Parenting Stress Index_ 3rd edn. (Psychological Assessment Resources, 1995). Google Scholar * Parry G, Tucker J, Tarnow-Mordi W, Group UKNSSC. CRIB II: an update of the

clinical risk index for babies score. _Lancet (Lond. England)._ 2003;361(9371):1789–1791. * Feldman, R. Parent-infant synchrony: A biobehavioral model of mutual influences in the formation

of affiliative bonds. _Monogr. Soc. Res. Child Dev._ 77(2), 42–51 (2012). Article Google Scholar * Feldman, R., Weller, A., Leckman, J. F., Kuint, J. & Eidelman, A. I. The nature of

the mother’s tie to her infant: maternal bonding under conditions of proximity, separation, and potential loss. _J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry_ 40(6), 929–939 (1999). Article CAS PubMed

Google Scholar * Moore, E. R., Bergman, N., Anderson, G. C. & Medley, N. Early skin-to-skin contact for mothers and their healthy newborn infants. _Cochrane Database Syst. Rev._ 11,

CD003519 (2016). PubMed Google Scholar * Pineda, R. _et al._ Parent participation in the neonatal intensive care unit: Predictors and relationships to neurobehavior and developmental

outcomes. _Early Human Dev._ 117, 32–38 (2018). Article Google Scholar * Davenport, M. H., Meyer, S., Meah, V. L., Strynadka, M.C., & Khurana, R. Moms Are Not OK: COVID-19 and Maternal

Mental Health. _Front. Glob. Womens Health_ 1, 1. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgwh.2020.00001(2020). * Manuela, F. _et al._ Maternal stress, depression, and attachment in the neonatal intensive

care unit before and during the COVID pandemic: an exploratory study. _Front. Psychol._ 12, 734640. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.734640 (2021). * Lemmon, B. E. _et al._ Beyond the

first wave: consequences of COVID-19 on high risk infants and families. _Am. J. Perinatol._ 37, 12831288. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0040-1715839 (2020). * O'Brien, K. _et al._

Effectiveness of Family Integrated Car in nenonatal intensive care units on infant and parents outcomes: a multicentre, multinational, clusterr-randomised controlled trial. _Lancet Child

Adolesc. Health_ 2(4), 245–254 (2018). * Moen A. If parents were a drug? _Acta Paediatrica_ 109(9), 1709–1710 (2020). * Le Bas, G. _et al._ The role of antenatal and postnatal maternal

bonding in infant development. _J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry_ 61(6), 820-829.e821 (2022). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Sansavini, A. _et al._ Dyadic co-regulation, affective

intensity and infant’s development at 12 months: A comparison among extremely preterm and full-term dyads. _Infant Behav. Dev._ 40, 29–40 (2015). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Korja,

R., Latva, R. & Lehtonen, L. The effects of preterm birth on mother-infant interaction and attachment during the infant’s first two years. _Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand._ 91(2), 164–173

(2012). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Mayopoulos, G. A. _et al._ COVID-19 is associated with traumatic childbirth and subsequent mother-infant bonding problems. _J. Affect. Disord._

282, 122–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.12.101 (2021). * Hagen, I. H, Iversen, V. C. & Svindseth, M. F. Differences and similiarities between mothers and fathers of premature

children: A qualitatie study of parents´ coping experiences in a neonatal intensive care unit. _BMC Pediatrics_ 16(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-016-0631-9 (2016). * Treyvaud, K.,

Spittle, A., Anderson, P.J., O'Brien, K. A multilayered approach is needed in the NICU to support parents after the preterm birth of their infant. _Early Hum. Dev._ 139, 104838.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2019.104838 (2019). * Erdei, C., Liu, C. H. The downstream effects of COVID-19: a call for supporting family well-being in the NICU. _J. Perinatol._

40(9), 1283–1285. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41372-020-0745-7 (2020). * Kostenzer, J., Hoffmann, J., von Rosenstiel-Pulver, C., Walsh, A., Zimmermann, L. J. I., Mader, S. Neonatal care during

the COVID-19 pandemic - a global survey of parents experiences regarding infant and family-centred developmental care. _EClinical Medicine_ 39, 101056 (2021). Download references

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We thank all the parents who participated in this survey. FUNDING There was no funding for this survey. AUTHOR INFORMATION Author notes * These authors contributed equally:

Philipp Deindl and Andrea Witting. AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Department of Neonatology and Pediatric Intensive Care Medicine, University Children’s Hospital, University Medical Center

Hamburg-Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany Philipp Deindl & Dominique Singer * Department of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, Division of Neonatology, Pediatric Intensive Care and

Neuropediatrics, Comprehensive Center for Pediatrics, Medical University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria Andrea Witting, Angelika Berger, Katrin Klebermass-Schrehof, Vito Giordano & Renate

Fuiko * Duervation, Krems, Austria Mona Dür * Department of Neurobiology, Care Sciences and Society, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden Mona Dür Authors * Philipp Deindl View author

publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Andrea Witting View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Mona Dür View

author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Angelika Berger View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar *

Katrin Klebermass-Schrehof View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Dominique Singer View author publications You can also search for this

author inPubMed Google Scholar * Vito Giordano View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Renate Fuiko View author publications You can also

search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CONTRIBUTIONS Dr V.G., and Dr R.F. conceptualized and designed the study, coordinated, and supervised data collection, and reviewed and revised

the manuscript. Dr A.W. developed the survey questionnaires, collected data, and revised and widened the initial manuscript for important intellectual content. Dr P.D. collected data,

conducted the statistical analyses, drafted the initial manuscript, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. Prof A.B. and Prof D.S. advised on the study design, and methods. In addition,

they helped interpret the data and critically revised the draft for important intellectual content. Prof K.K.-S. and Prof. M.D. were involved in the survey planning, helped develop the

survey design, and revised the draft critically for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the

work. CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to Vito Giordano. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS The authors declare no competing interests. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION PUBLISHER'S NOTE

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION SUPPLEMENTARY TABLE 1. SUPPLEMENTARY TABLE 2.

SUPPLEMENTARY TABLE 3. RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS OPEN ACCESS This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation,

distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and

indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit

line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use,

you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS

ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Deindl, P., Witting, A., Dür, M. _et al._ Perceived stress of mothers and fathers on two NICUs before and during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. _Sci Rep_ 13, 14540

(2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-40836-9 Download citation * Received: 28 March 2023 * Accepted: 17 August 2023 * Published: 04 September 2023 * DOI:

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-40836-9 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not

currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative