Play all audios:

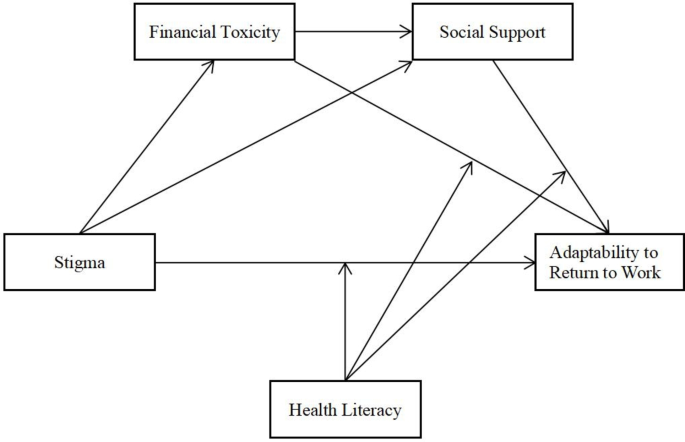

Adaptability to return to work is a process by which cancer survivors(CSs) utilize accessible resources to reconstruct themselves. While the stigma, financial situation and social support

are known to influence their adaptability to return to work, the mechanisms by which these factors work remain unclear. This study proposes a moderated mediation model to signify a pathway

linking stigma to the adaptability to return to work. Data were analyzed using the PROCESS macro for R version 4.3.1. A total of 238 CSs, aged between 18 and 60 years (73.5% female), of whom

42.1% had returned to work, completed the ARTWS, SIS, COST-PROM, SSRS, HeLMS. Stigma had a negative associations on the adaptability to return to work. Both financial toxicity and social

support mediated the relationship between stigma and the adaptability to return to work. Health literacy moderated both the direct pathway and the second half of the pathway mediated by

financial toxicity. Specifically, the negative effects of stigma and financial toxicity on the adaptability to return to work were significantly attenuated when health literacy levels were

high. CSs with higher health literacy may not experience excessive stigma, and experience less financial toxicity than those with lower health literacy. CSs possessing greater social support

will be more effective in utilizing external resources to buffer the influence of financial toxicity, and thus adapt better to work.

Cancer Survivors (CSs) are individuals who either live with cancer or have successfully managed to control their cancer following anticancer treatments (surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy,

etc.)1. According to statistics, the number of CSs continues to rise, with 47% of them surviving beyond 10 years post-diagnosis, and approximately 40–50% being of working age at the time of

diagnosis2,3. The diagnosis and treatment of cancer can have adverse impact CSs’ body image and physiological functions, causing external misunderstanding, alienation, and discrimination,

which may lead to social avoidance behaviors4. The psychological feelings triggered by this experience are referred to as stigma5. 13−80% CSs experience stigma related to their illness. Of

these, over 30% hold negative attitudes towards their cancer, and 10% report experiencing social discrimination6. Stangl et al.7 proposed the Cross-Domain Health Stigma and Discrimination

Framework, considering the interplay of multiple identities, social inequality, and health issues. This framework explains how health issues and stigmatization differ across economic

backgrounds within a socio-ecological context, and it emphasizes the internalization of stigma affecting cancer patients, leading to financial toxicity, social exclusion, and occupational

maladaptation. Subsequent studies8,9,10,11 have consecutively confirmed that the financial toxicity, behavior of seeking social support, and the adaptability to return to work among CSs are

not only influenced by stigma, but affect the occurrence and development of stigma. However, no studies have yet deeply explored the relationship among stigma, financial toxicity, social

support, and the adaptability to return to work.

It’s estimated that 48–72% of cancer patients suffer from financial toxicity12. High levels of financial toxicity can have adverse effects on the emotional state and social functioning of

CSs, increasing the challenges faced by CSs in their return to work11,13. Social support can reduce the financial toxicity, providing external resources necessary to cope with negative

events, enhancing CSs’ adaptability14,15. Scholars16,17 have suggested that support from colleagues, superiors, or vocational rehabilitation agencies can assist CSs in overcoming the

psychological barriers, boosting their self-confidence, enabling them to better adapt to work environments. In summary, there exists a certain relationship between financial toxicity and

social support, and these two factors may exacerbate or mitigate the impact of CSs’ negative emotions on their adaptability to return to work. However, this relationship remains unconfirmed

and warrants further exploration or verification. Given this, our study aims to construct a chained multiple mediation model to more clearly elucidate the relationship between the

independent variables and dependent variable.

Although there is a complex interplay among stigma, financial toxicity, social support, and the adaptability to return to work, this relationship is not entirely independent. Health

literacy, defined as the ability to acquire, understand, and apply health information for decision-making, is crucial to quality of work and life of CSs18. Health literacy serves not only as

a buffer, mitigating the adverse effects of financial toxicity to a certain extent, and enabling CSs to make informed decisions19. Furthermore, it diminishes their stigma perception,

enhances their ability to efficiently seek assistance, and, by elevating their social support level, indirectly bolster quality of life20,21. Consequently, logically deduces that health

literacy has the potential to alleviate the negative effects of stigma and financial toxicity on one’s adaptability to return to work, while reinforce the beneficial of social support.

However, the specific mechanisms underlying these effects remain to be further explored. This exploration is crucial for understanding the intricate relationships and combined impact of

these factors on an individual’s work integration.

In summary, stigma, health literacy, financial toxicity, and social support collectively influence an CSs’ adaptability to return to work. We delved into the impacts of these factors on the

adaptability in this study based on the Behavior Change Wheel (BCW). It is a behavioral model framework centered on the COM-B system (capacity, opportunity, motivation-behavior),

encompassing nine intervention functions and seven policy categories, and examining how internal and external factors, such as individuals, groups, and the environment, influence behavioral

change22. Specifically, stigma and financial toxicity may serve as external pressures and barriers that hinder individuals from taking proactive actions. Stigma not only diminishes CSs’

self-confidence and social competence but leads to their reluctance to seek or accept support from others. Meanwhile, financial toxicity imposes economic pressure on CSs due to high

treatment costs, further weakening their motivation to work. Conversely, social support and health literacy may represent external resources and internal capabilities that enhance their

adaptability. Social support plays a crucial role throughout the entire process of the BCW, providing necessary assistance and encouragement to CSs. Health literacy aids individuals in

acquiring skills, knowledge, and beliefs, potentially mitigating the negative impacts stemming from stigma, financial toxicity, and inadequate social support23. Thus, this study integrates

BCW theory to construct a moderated chain-mediated model, aiming to analyze and validate the following five hypotheses (See Fig. 1):

H1: Stigma negatively affects the adaptability to return to work for CSs(a direct negative effect);

H2: Stigma affects the adaptability through the mediation of financial toxicity (mediation model);

H3: Stigma influences the adaptability through the mediation of social support (mediation model);

H4: Stigma impacts the adaptability through a sequential mediation process involving both financial toxicity and social support (chain-mediation model);

H5: Varying levels of health literacy can influence the effectiveness of stigma, financial toxicity, and social support on adaptability (moderated chain-mediation model).

This study is a face-to-face cross-sectional survey conducted from July 2023 to February 2024, involving 238 CSs. Participants were recruited through various channels, including two

hospitals in Jiangsu Province and Cancer Rehabilitation Association. The whole study process was based on the Declaration of Helsinki, ethics approval was obtained from the Human Research

Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Hospital of Nantong University (Approval number: 2023-K090−01), and all participants provided informed consent.

Inclusion criteria: pathological diagnosis of malignancy, completion of routine treatment with subsequent recovery or follow-up stage, having had a job before treatment, having resumed some

work, and being aged 18–60. Exclusion criteria: multiple cancer metastases, mental illness, and communication barriers.

Sample size was determined based on the number of items in the outcome indicator (24-item ARTWS). By multiplying the number of questionnaire items by 10 and considering a 10% margin for

invalid questionnaires, the total sample size was adjusted to a range of 132 to 264 cases. For the sample size calculation based on a cross-sectional study, we used α=0.05, which corresponds

to Z1-α/2=1.96. According to related research9, we have u = 87.05, σ=20.26, and p = 58.7%. With a relative allowable error set at 0.05, δ=87.05 × 0.05 ≈ 4.35. Using these values, the

minimum required sample size is calculated as (1.96 × 20.26/4.35)^2 ≈ 83. Statistical significance in the study was indicated by P