Play all audios:

ABSTRACT Although it is generally recognized that symptom clusters and quality of life are related, major ambiguity arises from the difficulty in determining their causal relationship. The

present study aimed to investigate longitudinal causal relationships between symptom clusters and quality of life. 128 patients with rectal cancer from Nanchong City, Sichuan Province who

underwent laparoscopic anus-preserving surgery completed 4 follow-up visits, and the survey time point are 2 weeks after surgery (T1), 1 month after surgery (T2), 3 months after surgery

(T3), and 6 months after surgery (T4). We used the Anderson Gastrointestinal Cancer Symptom Assessment Scale and the Colorectal Cancer Quality of Life Measurement Scale to evaluate the

patient’s symptom incidence, symptom severity, and quality of life at four time points respectively. After extracting symptom clusters by symptom, we constructed A four-wave cross-lagged

model analyzed the causal relationship between symptom clusters and quality of life. Our research results show that the patients with rectal cancer treated by laparoscopic anus-preserving

surgery have four symptom clusters during the 6 months after surgery, which are named sickness symptom cluster, gastrointestinal symptom cluster, psychological-sleep symptom cluster and

Psycho-therapy related symptom clusters. Pearson correlation analysis showed that symptom clusters and quality of life were negatively correlated. The cross-lagged path effect coefficient

shows that the impact of quality of life on symptom clusters is stronger than the impact of symptom clusters on quality of life (β = − 0.164 to − 0.713, _P_<0.05). The four-wave

cross-lagged model showed that quality of life can significantly negatively predict the sickness symptom cluster and gastrointestinal symptom cluster, but this relationship is not

bidirectional. Only T3 quality of life significantly negatively predicted the psycho-sleep symptom cluster, and the reverse path was also not observed. These findings provide evidence that

decreases in quality of life levels precede increases in symptom cluster severity. There is a one-way temporal correlation between symptom clusters and quality of life. The decrease in

quality of life leads to an increase in the severity of symptom clusters. The improvement in overall quality of life is expected to alleviate the distress of symptom clusters. SIMILAR

CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS DEVELOPMENT AND PRELIMINARY VALIDATION OF A PROS SCALE FOR CHINESE BLADDER CANCER PATIENTS WITH ABDOMINAL STOMA Article Open access 25 January 2024

CANCER-RELATED FATIGUE TRAJECTORIES UP TO 5 YEARS AFTER CURATIVE TREATMENT FOR OESOPHAGEAL CANCER Article Open access 22 December 2023 STUDENTS AND PHYSICIANS DIFFER IN PERCEPTION OF QUALITY

OF LIFE IN PATIENTS WITH TUMORS OF THE UPPER GASTROINTESTINAL TRACT Article Open access 24 April 2024 INTRODUCTION Colorectal cancer is the third and second most common cause of cancer

morbidity and mortality1. According to the latest statistics, there will be nearly 2 million new cases of colorectal cancer worldwide in 2020, including approximately 700,000 cases of rectal

cancer2. The number of new rectal cancer cases in China in 2020 is 560,000, making it one of the countries with the highest number of new colorectal cancer cases in the next 20 years1. With

the advancement of cancer treatment, the 3-year and 5-year survival rates of rectal cancer patients treated by laparoscopic surgery have increased to 79.3% and 60.3% respectively3. In

recent years, the adoption of minimally invasive techniques and the growing desire for anus preservation have driven laparoscopic anus preservation surgery to account for 62–85%, emerging as

the primary surgical approach for rectal cancer cure4. Despite its potential to maintain normal defecation function, sphincter-preserving surgery frequently subjects patients to a

constellation of physical and psychological symptoms stemming from factors like anatomical and physiological alterations, sphincter damage, changes in colonic motility, surgical irritation,

and postoperative radiotherapy and chemotherapy5,6. These symptoms often co-occur, forming symptom clusters that exhibit a reinforcing and cumulative impact, significantly impinging on

patient’s functional well-being and quality of life, and some times even reducing their survival prospects7. Symptom cluster was defined as the simultaneous occurrence of two or more

interrelated symptoms, and it is not necessarily to have the same etiological mechanism in each symptom7. Due to synergistic and reinforcing effects between symptoms within symptom clusters,

symptom clusters have a greater adverse impact on treatment outcomes, prognosis, functional status, and quality of life than individual symptoms8. Studies have shown that patients with

gastrointestinal cancer have psychological and emotional symptom clusters, and their severity is inversely proportional to quality of life8. Previous studies have provided that colorectal

cancer survivors will experience many symptoms, such as physical or psychological subjective signs, depression, body image changes, sexual dysfunction, etc9,10,11. These symptoms are usually

important feedback of abnormal states caused by disease or injury, which can cause survivor’s functional status and quality of life decline throughout the survival period12. Although

previous cross-sectional studies have shown there are a negative relationship between symptom clusters and quality of life, higher symptom cluster severity is a risk factor for lower quality

of life13,14,15. However, some research results still show that because cancer survivors have significant individual discrepency in perceived symptom clusters, priority symptom clusters,

symptom duration, and the relationship between cluster symptoms, not all symptom clusters will have a clinical impact on quality of life. For example, He et al. found that by intervening in

the fatigue-sleep disorder-depression symptom cluster, the physical and functional health dimensions of patients; quality of life would be improved, but the social, family, and emotional

health dimensions had no significant impact16. These results reflect a fact that the impact of symptom clusters on quality of life is limited and the temporal causal associations between

them remain largely unknown. In an era marked by a rising incidence of rectal cancer among younger population, it is crucial to elucidate the direction and magnitude of the link between

symptom clusters and quality of life. This understanding can inform the development and adaption of targeted preventive tragedies, with a focus on early stage patients. However, the

interaction between symptom clusters and quality of life may be bidirectional, making it challenging to discern causal predictive relationships. The influence of quality of life on changes

in the severity of symptom clusters has not been extensively documented. Quality of life encompasses various dimensions of an individual’s overall health, including physical functions,

psychological well-being, social relationships, and more17. It is generally believed that symptoms occur simultaneously with clinically significant declines in physical, cognitive, and

social functions13, It can be seen that the decline in quality of life will inevitably lead to the occurrence of symptoms and changes in symptom frequency and severity. However, the impact

of quality of life on symptom clusters is multidimensional. In terms of physical function dimensions, some studies have shown that the disease course and stage of digestive tract cancer

survivors have a significant impact on the severity of symptom clusters18, while others have indicated no significant relationship between them19. The impact of social relationships on

symptom clusters is not direct generation. Previous research has shown that the diagnosis of cancer will change an individual’s social network and reduce the patient’s perception of the help

provided by the social network during the illness. Social support, especially family support, can improve the symptoms of cancer survivors by strengthening psychological adjustment20. The

role of the psychological function dimension is more complex. Some studies have shown that distress, sadness, and anxiety will lead to an increase in the severity of symptom clusters18,

while others have indicated no significant relationship between them21. This conflicting evidence suggests that improvements or decreases in aspects of quality of life may contribute

positively or negatively to changes in symptom cluster severity. The available data on symptom clusters and quality of life are limited, and yield mixed results. It is crucial to elucidate

the temporal characteristics of their relationship. This understanding will help determine whether a decrease in the level of quality of life leads to an increase in the severity of the

symptom cluster or vice versa. To the best of our knowledge, no prior study has investigated changes in the symptom cluster and quality of life at multiple time points in patients following

laparoscopic anus-preserving surgery for rectal cancer. This gap in knowledge hampers our ability to comprehend these temporal dynamics. Notably, previous longitudinal studies have relied on

conventional longitudinal analysis models that do not specifically address temporal relationships. Consequently, this study examines symptom clusters and quality of life in patients within

6 months after laparoscopic anus-preserving surgery for rectal cancer. Utilizing a cross-lagged model, we introduce a temporal dimension to rigorously analyze the bidirectional correlation

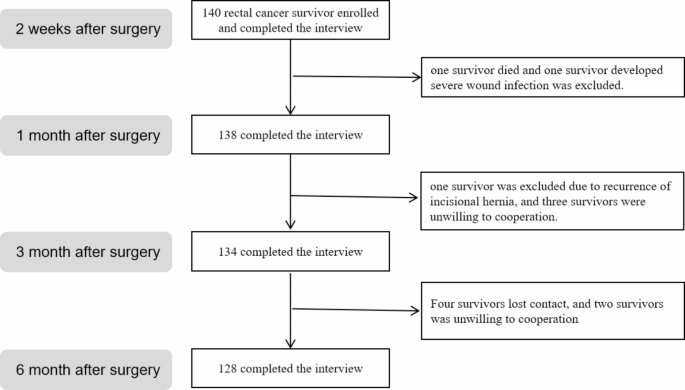

between them, providing valuable insights foe the identification of potential intervention strategies. METHODS PARTICIPANTS AND PROCEDURE We conducted a four-wave survey, the participants

were rectal cancer patients who undergoing laparoscopic-assisted anus-preserving surgery from the Affiliated Hospital of North Sichuan Medical College in Nanchong City, Sichuan Province. A

total of 140 eligible patients aged ≥ 18 years old were enrolled from November 2021 to October 2022. Participants were invited to participate in the study during their hospitalization and

left their contact information and address. 2 trained researchers (Zhou Yi, Zhang Xiaoxuan) introduced the purpose and content of our study to them, and recorded their demographic

characteristics and disease-related information. 4 researchers (You Chaoxiang, Jia Mengyao, Li Shuang, and Wu Xiufei) used paper questionnaires by Face-to-face interviews or telephone

interviews assess symptoms and quality of life at 2 weeks after surgery (T1), 1 month after surgery (T2), 3 months after surgery (T3), and 6 months after surgery(T4) respectively. The

interview will take approximately 30 min to complete. Participants will be excluded if their tumors recur or metastasize during follow-up, are lost to follow-up, refuse to participate, or

develop severe postoperative complications. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Hospital of North

Sichuan Medical College (Reference No: 2022ER171-1), and written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Participants interviewed at four time points were 140 (T1), 138 (T2),

134 (T3), and 128 (T4). Only the last 128 participants who completed 4 follow-up visits were included in the data analysis (see Fig. 1). SAMPLE SIZE CALCULATION Using the sample size

calculation formula for repeated measurement data in a single group

\(\:\:\text{N}=[1+(\text{k}-1\left){\uprho\:}\right]\frac{{{\upsigma\:}}^{2}{({\text{Z}}_{\raisebox{1ex}{${\upalpha\:}$}\!\left/\:\!\raisebox{-1ex}{$2$}\right.}+{\text{Z}}_{{\upbeta\:}})}^{2}}{\text{k}{{\updelta\:}}^{2}}\)22.

According to the preliminary experimental results of 20 participants, the internal correlation coefficient ρ is 0.541. The sample standard deviation of the participant’s quality of life 2

weeks after surgery (T1) is used instead of the overall standard deviation σ to be 5.35. The allowable error δ is 0.25 times the standard deviation, that is 1.34. k is the number of

measurements, k=4. Zα/2 = 1.96, Zβ = 0.84, and considering the loss to follow-up rate of 15–20%, the sample size of this study was finally determined to be 95 to 99 cases. According to the

requirements of the cross-lagged model, it is recommended that the minimum sample size is >100, and the sample size of 128 cases in our study met the standard. MEASURES BASIC INFORMATION

A self-designed questionnaire was utilized to gather demographic characteristics and disease-related information including age, gender, smoking history, drinking history, body mass index,

operation mode, distance from lower margin of tumor to anal margin. SYMPTOM CLUSTER MEASURE Symptom clusters were assessed using the Chinese version of the Anderson Gastrointestinal Cancer

Symptom Assessment Scale. This scale is a universally applicable self-report scale for assessing multiple symptoms and was developed by Cleeland et al. in 2000 at the University of Texas MD

Anderson Cancer Center23. It has been translated into 29 languages, and specific modules tailored to patients with different cancer type have been adapted. In our study, we utilized the

Chinese version of the Anderson Symptom Assessment Scale’s gastrointestinal tumor-specific assessment module designed for patients with gastrointestinal cancer24. It includes 13 core

symptoms and 5 gastrointestinal tumor-specific symptoms that are most commonly or severely experienced by patients with various cancers. A total of 18 symptoms are used to gauge symptom

severity over past 24 h. Each item in this section is rated on a scale from 0 to 10, with 0 indicating an absence of symptoms and 10 signifying the most severe possible symptom. The

Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the scale are 0.84, indicating strong reliability and validity25. In our study, the measured Cronbach’s alpha coefficient range from 0.701 to 0.813. QUALITY

OF LIFE MEASURE Quality of life was evaluated using the Colorectal Cancer Patients Quality of Life Measurement Scale, a quality of life assessment tool designed for cancer patients with

Chinese cultural characteristics, which was developed by Yang Zheng et al. in 200826. This scale encompasses general modules applicable to cancer patients and specific modules tailored for

colorectal cancer patients. It comprises five domains: physical function, psychological function, social function, common symptoms and specific modules, totaling 46 items. Each item is rated

on a five point scale: not at all, a little, somewhat, quite a bit, and very much. For scoring, forward items are directly assigned values from 1 to 5 points, while reverse items are scored

reversely. This scale exhibits robust reliability and validity, with Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of 0.63 and 0.66 in the common symptoms and side effects domain and the social function

domain, respectively. For other domains and common modules, Cronbach’s alpha values consistently exceed 0.85. In our study, the measured Cronbach’s alpha ranged from 0.776 to 0.830. Higher

scores on this scale correspond to better quality of life, whereas lower scores indicate lower quality of life. STATISTIC ANALYSIS IBM SPSS statistical software for Windows (version 26.0)

was employed to calculate the differences in various dimensions of quality of life at different points in time. Descriptive statistics were utilized to present the characteristics of the

participant. The included reporting frequencies and percentages for categorical variables and means and standard deviations for continuous variables. To assess the longitudinal changes in

quality of life scores at the four time points, repeated measures analysis of variance was conducted. Furthermore, the Friedman test was applied to evaluate the longitudinal changes in

symptom cluster severity scores at the four time points, with significance level set at 0.05. Subsequently, exploratory factor analysis was utilized to identify symptom cluster, Symptom with

an incidence rate of ≥ 15% at different time points were included in the factor analysis27. The following principles guide the extraction of symptom clusters: ① initial eigenvalue ≥ 1; ②

factor loading > 0.5; ③ factors comforming to Cartel’s “steep order” test principle; ④ factors consisting of at least two items. Symptom clusters were named based on clinical expertise.

To explore the correlation between symptom clusters and quality of life, Pearson correlation analysis was employed. In the next step, to examine the relationship between symptom clusters and

quality of life, a cross-lagged model was conducted and analyzed using Mplus8.0. In this analysis, covariates were included based on previous data that demonstrated associations with

predictor or outcome variables. There covariates encompassed age, drinking history, smoking history, distance from the lower edge of the tumor to the anal verge, operation mode. The

cross-lagged model, a structural model assessing interaction and longitudinal relationships between variables. Four models were constructed to elucidate the causal predictive relationship

between symptom clusters and quality of life: (1) Model 1 a stability model with symptom clusters and quality of life, devoid of cross-labeled structural paths. (2) Model 2 building on Model

1, it incorporates a cross-lagged path from symptom clusters to quality of life. (3) Model 3 an extension of Model 2, it adds a cross-lagged path from quality of life to symptom cluster.

(4) Model 4 includes all autoregressive and cross-lagged paths from Model 1–3. These measures were repeated while exploring the bidirectional temporal relationship between each symptom

clusters and quality of life. Standardized beta coefficients were employed to determine and compare the strength of associations. Model fitting effectiveness was evaluated using the

following criteria: Comparative Fit Index(CFI) ≥ 0.95, Tucker-Lewis Index(TLI) ≥ 0.95, Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) ≤ 0.08, and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation

(RMSEA) ≤ 0.06. A significance level of _P_ < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Chi-square difference tests were conducted to compare difference between nested models. It is

noteworthy that previous literature recommended including more than 100 participants in any Mplus model, sand this study exceeded this requirement at all four time points. RESULTS

DEMOGRAPHIC CHARACTERISTICS AND DISEASE-RELATED INFORMATION As is shown in Table 1, the mean age of subjects was 64.4 (SD = 12.2) years. Most of the participants were male (65.5%) and nearly

60% of them had body mass index in 18.5 –23.9 kg/m2. Most are without drinking history(70.1%) and smoking history(61.6%). 60.4% had conventional laparoscopic surgery, 51.5% had tumors

located in the mid-rectum (see Table 1). SYMPTOM CLUSTER As shown in Tables 2 and 3, a total of 4 groups of symptom clusters were extracted, which were named sickness symptom cluster,

gastrointestinal symptom cluster, psychological-sleep symptom cluster, and psychological-treatment-related symptom cluster. The psychotherapy-related symptom cluster only exists at the T1

time point, and the other three groups of symptom clusters all exist at the T2 ~ T4 time point. Gastrointestinal symptom cluster is the most severe and show a high degree of stability.

QUALITY OF LIFE As is shown in Table 4, the quality of life remained above (70.87 ± 7.05) points within 6 months after surgery and showed an increasing trend in stages. DESCRIPTIVE

STATISTICS AND CORRELATIONS As is shown in Table 5, the correlation coefficients of quality of life at four survey wave showed a significant moderate to strong correlation (_r_= − 0.369 ~

-0.661, _P_ < 0.01). The correlation coefficients between gastrointestinal symptom cluster and quality of life was strongest at T1 and T2 respectively, revealing close relationships

between them. The correlation coefficients between psychological-sleep symptom cluster and quality of life were significant at different time and was strongest at T3 and T4, while other

symptom cluster were not observed. Suggesting that there may be a potential pathway for psychological-sleep to predict quality of life decline. THE CROSS-LAGGED MODEL Building upon the

findings of the correlation analysis, We constructed a cross-lagged model to analyze the magnitude and directionality of the relationship between symptom clusters and quality of life (see

Figs. 2, 3 and 4). The results of the model fitting for the cross-lagged relationship between symptoms clusters and quality of life see in Supplementary data. Cross-lagged path coefficients

showed a negative relationship between quality of life and each symptom clusters. We observed that quality of life at each survey wave statistically significantly predicted sickness symptom

cluster at the next wave (standardized path coefficients from−0.111 (_P_ < 0.05) to−0.237 (_P_ < 0.001)). The same pattern occurred for repeated measures of quality of life and

gastrointestinal symptom clusters over time (standardized path coefficients from−0.051 (_P_ < 0.05) to−0.252 (_P_ < 0.01)), and these coefficients were higher than sickness symptom

cluster. However, only the quality of life at T3 could significantly significantly negative predict the psychological-sleep symptom cluster (standardized path coefficient was − 0.540 (_P_

< 0.001)). In addition, all three models show that the effect of quality of life on symptom clusters is stronger than the effect of symptom clusters on quality of life. Cross-lagged path

effects are critical to our study hypotheses, it suggests that the deterioration in quality of life may be associated with the heightened severity of symptom clusters. The temporal stability

of gastrointestinal symptom cluster is higher than that of sickness symptom cluster and psychological-sleep symptom cluster. SENSITIVITY ANALYSIS In order to evaluate the stability of

bidirectional temporal relationship between symptom cluster and quality of life and eliminate the effects of confounding variable. we included gender, age, distance between the lower edge of

the tumor and the anal verge, surgical method as covariates in the above three models, there was no significant difference between the standardized regression coefficients. It shows that

after controlling for more confounding variables, quality of life can still significantly and negatively predict symptom clusters, while symptom clusters do not significantly predict quality

of life. DISCUSSION We constructed a cross-lagged model to study whether there is a bidirectional predictive relationship between symptom clusters and quality of life in rectal cancer

survivors, and found three important results, which were partially consistent with our research hypothesis. Firstly, rectal cancer patients treated by laparoscopic anus-preserving surgery

have four symptom clusters within 6 months after surgery, which are named sickness symptom cluster, gastrointestinal symptom cluster, psychological-sleep symptom cluster, and

psychological-treatment related symptom clusters. In addition, quality of life and symptom clusters were negatively correlated, and the impact of quality of life on each symptom cluster was

stronger than the impact of each symptom cluster on quality of life. Finally, the quality of life in the four survey waves can significantly and negatively predict the sickness symptom

cluster and gastrointestinal symptom cluster, but this relationship is not bidirectional. Only the quality of life at T3 can negatively predict the psychological-sleep symptom cluster, and

the reverse path was also not observed. Our study found that as time progresses, symptom clusters exhibit the characteristics of longitudinal stability and horizontal dynamic variability of

internal symptoms. Symptom clusters do not contain exactly the same symptoms at different investigation time points. The sickness symptom cluster persisted throughout the entire

investigation period, and forgetfulness, fatigue, drowsiness, and dry mouth were the main symptoms constituting this symptom cluster, which was similar to the research results of Hao Tie et

al.28. The gastrointestinal symptom cluster is the core symptom cluster of this patients, with the highest severity, and the internal symptom composition shows a high degree of stability

during the entire investigation cycle. Abdominal distension and diarrhea constitute the main symptom of this symptom cluster. Psychological-sleep symptom cluster appears from T2 to T4, and

distress, sadness, and restless sleep constitute the main symptom of this symptom cluster. The psychotherapy-related symptom cluster is a symptom cluster unique to T1 in this type of patient

and consists of five symptoms: distress, sadness, dry mouth, pain, and numbness. This symptom cluster is a comprehensive manifestation of psychological symptoms, symptoms of toxic and side

effects of adjuvant chemotherapy, and symptoms of surgical trauma, indicating that these symptoms may have a potential common biological etiological mechanism29. Our study found that the

total quality of life score of rectal cancer patients treated with laparoscopic anus-preserving surgery remained above (70.87 ± 7.05), which is at a medium to high level, consistent with the

research results of Pappou et al.30. At the same time, during the 6-month follow-up, the changes in quality of life levels showed a medium-to-high strength correlation (_r_ = 0.369 ~ 0.661,

_P_ < 0.01), indicating that the changing trend of patients’ long-term quality of life levels is closely related to their basic quality of life levels. Suggesting that we should pay

attention to patients with low basic quality of life. In addition, previous studies generally believe that symptom clusters are the affecting factors of quality of life31,32. However, the

three cross-lagged models we constructed all showed that the impact of quality of life on symptom clusters was stronger than the impact of symptom clusters on quality of life. The reason may

be that the quality of life assessment scale used in this study includes overall scores for multiple dimensions such as psychological function, physical function, colorectal cancer-specific

symptoms, etc., while the symptom cluster is only a specific manifestation of one of its dimensions. Several studies have shown that not all symptom clusters are factors affecting quality

of life33,34. At the same time, not only can symptom clusters affect changes in a certain functional dimension of quality of life, but also different symptom clusters affect different

functional dimensions of quality of life, which also provides a basis for our view33,35. Research shows that interventions targeting underlying mechanisms of symptom clusters are considered

more cost-effective than interventions targeting individual symptoms, suggesting that developing interventions targeting symptom clusters may improve the functional status of a certain

dimension of quality of life, thereby improving the overall quality of life of patients16. A key finding of our study is that quality of life level significantly and negatively predicts the

severity of the sickness symptom cluster, gastrointestinal symptom cluster, and psycho-sleep symptom cluster, but this relationship is not bidirectional. This suggests that quality of life

level can predict the severity of subsequent symptom clusters, with decreases in quality of life levels preceding increases in symptom cluster severity, and symptom cluster severity being an

expression of high or low quality of life levels. Our research results are opposite to those of Lin et al.35. The reason may be that the research subjects of Lin et al. were breast cancer

patients. Sleep disorders and cancer-related fatigue are the core symptoms of them, which have a strong impact on the quality of life. Our study included symptom clusters, which are the

superposition of symptoms with a common etiological mechanism and are manifestations of abnormal functional status in a certain dimension of quality of life, they cannot predict the level of

quality of life. It reminds us that we should pay attention to the assessment of all aspects of quality of life and develop targeted intervention measures for functional dimensions with

high degree of damage, which may get twice the result with half the effort. It is worth noting that T2 quality of life did not significantly predict T3 psycho-sleep symptom cluster severity,

and the reverse path was also not observed. The reason may be that the cross-lagged effect path coefficient of the two at this point is low (β= 0.134), indicating that the correlation

between them is not strong, and this symptom cluster is not a key influencing factor on the quality of life at this point. STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS This study used a new statistical model

to measure the causal relationship between symptom clusters and quality of life, providing evidence for exploring potential intervention mechanisms for both. But there are certain

limitations. Firstly, this study used a questionnaire method to assess the severity of symptom incidence. The questionnaire method itself has subjective biases that are difficult to

overcome, which may affect the authenticity of patient’s answers. Future studies should employ implicit methods or combine physiological and neurological indicators as measures in laboratory

settings to obtain a more objective and diverse source of data. Secondly, there may be some mediating variables that interfere with the relationship between symptom clusters and quality of

life, and the inclusion of mediating variables may help to quantify their relationship more accurately. DATA AVAILABILITY The raw data are not publicly available due to the participant’s

privacy, but derived data supporting the findings are available from the corresponding author by reasonable request. REFERENCES * Xi, Y. & Xu, P. Global colorectal cancer burden in 2020

and projections to 2040[J]. _Transl Oncol._ 14 (10), 101174 (2021). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Morgan, E. et al. Global burden of colorectal cancer in 2020 and 2040:

incidence and mortality estimates from GLOBOCAN[J]. _Gut_ 72 (2), 338–344 (2023). Article PubMed MATH Google Scholar * Benson, A. B. et al. Rectal Cancer, Version 2.2022, NCCN Clinical

Practice guidelines in Oncology[J]. _J. Natl. Compr. Canc Netw._ 20 (10), 1139–1167 (2022). Article PubMed MATH Google Scholar * Shahjehan, F. et al. Trends and outcomes of

sphincter-preserving surgery for rectal cancer: a national cancer database study[J]. _Int. J. Colorectal Dis._ 34 (2), 239–245 (2019). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Li, C. et al.

Experiences of bowel symptoms in patients with rectal cancer after sphincter-preserving surgery: a qualitative meta-synthesis[J]. _Support Care Cancer_. 31 (1), 23 (2022). Article PubMed

Google Scholar * Custers, P. A. et al. Long-term quality of life and functional outcome of patients with rectal Cancer following a Watch-and-wait Approach[J]. _JAMA Surg._ 158 (5), e230146

(2023). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Harris, C. S. et al. Advances in conceptual and methodological issues in Symptom Cluster Research: a 20-Year Perspective[J]. _ANS

Adv. Nurs. Sci._ 45 (4), 309–322 (2022). Article PubMed PubMed Central MATH Google Scholar * Wang, K. et al. Identification of Core Symptom Cluster in patients with Digestive Cancer: A

Network Analysis[J]. _Cancer Nurs._, (2023). * Sheikh-Wu, S. F. et al. Positive psychology mediates the relationship between symptom frequency and quality of life among colorectal cancer

survivors during acute cancer survivorship[J]. _Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs._ 58, 102136 (2022). Article PubMed MATH Google Scholar * Sheikh-Wu, S. F. et al. The Relationship between Colorectal

Cancer survivors’ positive psychology, Symptom characteristics, and prior trauma during Acute Cancer Survivorship[J]. _Oncol. Nurs. Forum_. 50 (1), 115–127 (2022). PubMed Google Scholar *

Luo, X. et al. Analyzing the symptoms in colorectal and breast cancer patients with or without type 2 diabetes using EHR data[J]. _Health Inf. J._ 27 (1), 1187486161 (2021). Google Scholar

* Sheikh-Wu, S. F. et al. Symptom occurrence, frequency, and Severity during Acute Colorectal Cancer Survivorship[J]. _Oncol. Nurs. Forum_. 49 (5), 421–431 (2022). PubMed Google Scholar *

Potosky, A. L. et al. The prevalence and risk of symptom and function clusters in colorectal cancer survivors [J]. _J. Cancer Surviv_. 16 (6), 1449–1460 (2022). Article PubMed MATH Google

Scholar * Luo, Y. et al. _Symptom Clusters and Impact on Quality of life in lung cancer Patients Undergoing chemotherapy[J]_ (Qual Life Res, 2024). * Lu, X. et al. Symptom clusters and

sentinel symptoms in breast cancer survivors based on self-reported outcomes:a cross-sectional survey [J]. _J. Clin. Nurs._, (2024). * He, X. et al. Effects of a 16-week dance intervention

on the symptom cluster of fatigue-sleep disturbance-depression and quality of life among patients with breast cancer undergoing adjuvant chemotherapy: a randomized controlled trial[J]. _Int.

J. Nurs. Stud._ 133, 104317 (2022). Article PubMed MATH Google Scholar * Haraldstad, K. et al. A systematic review of quality of life research in medicine and health sciences[J]. _Qual.

Life Res._ 28 (10), 2641–2650 (2019). Article PubMed PubMed Central MATH Google Scholar * Poon, M. et al. Symptom clusters of gastrointestinal cancer patients undergoing radiotherapy

using the functional living index-Emesis (FLIE) quality-of-life tool[J]. _Support Care Cancer_. 23 (9), 2589–2598 (2015). Article PubMed MATH Google Scholar * Adams, S. V., Ceballos, R.

& Newcomb, P. A. Quality of Life and Mortality of Long-Term Colorectal Cancer survivors in the Seattle Colorectal Cancer Family Registry[J]. _PLoS One_. 11 (6), e156534 (2016). Article

MATH Google Scholar * Wang, Y. et al. Symptom clusters and impact on quality of life in esophageal cancer patients[J]. _Health Qual. Life Outcomes_. 20 (1), 168 (2022). Article PubMed

PubMed Central MATH Google Scholar * Rha, S. Y. & Lee, J. Symptom clusters during palliative chemotherapy and their influence on functioning and quality of life[J]. _Support. Care

Cancer_. 25 (5), 1519–1527 (2017). Article PubMed MATH Google Scholar * Li, Q. R. et al. The trajectory of Stoma Acceptance in patients with enterostomy and its influencing Factors[J].

_Mil Nurs._ 40 (1), 36–39 (2023). MATH Google Scholar * Cleeland, C. S. et al. Assessing symptom distress in cancer patients: the M.D. Anderson Symptom Inventory[J]. _Cancer_ 89 (7),

1634–1646 (2000). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Wang, X. S. et al. Validation and application of a module of the M. D. Anderson Symptom Inventory for measuring multiple symptoms in

patients with gastrointestinal cancer (the MDASI-GI)[J]. _Cancer_ 116 (8), 2053–2063 (2010). Article PubMed MATH Google Scholar * Wang, X. S. et al. Chinese version of the M. D. Anderson

Symptom Inventory: validation and application of symptom measurement in cancer patients[J]. _Cancer_ 101 (8), 1890–1901 (2004). Article PubMed MATH Google Scholar * Yang, Z. et al.

Development of the System of Quality of Life I nstruments for Cancer patients: colorectal Cancer(QLICP-CR)[J]. _Cancer_ 27 (1), 96–100 (2008). MATH Google Scholar * Li, N. N. et al.

Analysis of symptom groups and influencing factors for patients with lung cancer chemothrapy[J]. _J. Nurses Train._ 33 (22), 2029–2032 (2018). MATH Google Scholar * Tie, H. et al. Symptom

clusters and characteristics of cervical cancer patients receiving concurrent chemoradiotherapy: a cross-sectional study[J]. _Heliyon_ 9 (12), e22407 (2023). Article PubMed PubMed Central

MATH Google Scholar * Amirkhanzadeh, B. Z. et al. Associations of inflammation with neuropsychological symptom cluster in patients with Head and neck cancer: a longitudinal study[J].

_Brain Behav. Immun. Health_. 30, 100649 (2023). Article MATH Google Scholar * Pappou, E. P. et al. Quality of life and function after rectal cancer surgery with and without sphincter

preservation[J]. _Front. Oncol._ 12, 944843 (2022). Article PubMed PubMed Central MATH Google Scholar * Li, Y. et al. Symptom clusters and their impact on quality of life among Chinese

patients with lung cancer: a cross-sectional study[J]. _Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs._ 67, 102465 (2023). Article PubMed MATH Google Scholar * Chen, K. et al. Changes in the symptom clusters of

elderly patients with lung cancer over the course of postoperative rehabilitation and their correlation with frailty and quality of life: a longitudinal study[J]. _Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs._ 67,

102388 (2023). Article PubMed MATH Google Scholar * Yang, X. et al. Symptom clusters and their impacts on the quality of life of patients with lung cancer receiving immunotherapy: A

cross-sectional study[J]. _J. Clin. Nurs._, (2024). * Yao, Q. et al. The Effect of Heart failure Symptom clusters on quality of life: the moderating effect of self-care Behaviours[J]. _J.

Clin. Nurs._, (2024). * Brazauskas, R. et al. Symptom clusters and their impact on quality of life in multiple myeloma survivors: secondary analysis of BMT CTN 0702 trial[J]. _Br. J.

Haematol._ 204 (4), 1429–1438 (2024). Article PubMed MATH Google Scholar Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We thank all the participants in the study, and we are also grateful to

research assistants who participated in the study for their assistance in research coordination and data collection. AUTHOR INFORMATION Author notes * These authors contributed equally:

Chaoxiang You, Guiqiong Xie and Shun Lin. AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Department of Gastroenterology, Deyang People’s Hospital, Deyang, 618000, Sichuan, China Chaoxiang You & Guiqiong Xie

* Department of Gastrointestinal Surgery, Affiliated Hospital of North Sichuan Medical College, Nanchong, 637000, Sichuan, China Shuang Li, Mengying Jia, Xiufei Wu, Xiaoxuan Zhang, Yi Zhou

& Hongyan Kou * Departmen of Pediatrics, The Second People’s Hospital of Deyang, Deyang, 618000, Sichuan, China Shun Lin Authors * Chaoxiang You View author publications You can also

search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Guiqiong Xie View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Shun Lin View author publications You can

also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Shuang Li View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Mengying Jia View author publications

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Xiufei Wu View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Xiaoxuan Zhang View author

publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Yi Zhou View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Hongyan Kou View

author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CONTRIBUTIONS Z.Y, Z.X.X, W.X.F, performed the measurements. Y.C.X, X.G.Q and K.H.Y designed the model. Y.C.X

and K.H.Y designed the computational framework and analysed the data. Y.C.X, J.M.Y and L.S conceived the original project. K.H.Y and X.G.Q supervised the project. J.M.Y and Y.C.X

pre-analysed and prepared the heart rate data and contributed to the interpretation of the findings. Y.C.X and X.G.Q took the lead in writing the manuscript. All authors discussed the

results and contributed to the final version of the manuscript. CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to Hongyan Kou. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS The authors declare no competing

interests. ETHICAL APPROVAL The ethical approval was acquired from Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Hospital of North Sichuan Medical College (Reference No: 2022ER171-1). INFORMED CONSENT

The written consent was obtained from all participants before the study. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION PUBLISHER’S NOTE Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in

published maps and institutional affiliations. ELECTRONIC SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material. SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL 1 RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS

OPEN ACCESS This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution

and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you

modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in

this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative

Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a

copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE You, C., Xie, G., Lin, S. _et al._ Temporal

relationship between symptom cluster and quality of life in rectal cancer patients after laparoscopic anus-preserving surgery. _Sci Rep_ 14, 32079 (2024).

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83755-z Download citation * Received: 06 February 2024 * Accepted: 17 December 2024 * Published: 30 December 2024 * DOI:

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83755-z SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not

currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative KEYWORDS * Rectal neoplasm * Symptom cluster * Quality of life *

Bidirectional relationship