Play all audios:

ABSTRACT This paper sheds light on the importance of evaluating climate justice concerns when forging climate-neutral strategies at the city level. Climate justice can be a useful policy

lever to develop measures that promote simultaneously greenhouse gas emissions reductions and their social justice dimension, thus reducing the risk of adverse impacts. As a result,

evaluating policymakers’ awareness of (i) recognition (ii) distributive (iii) procedural, and (iv) intergenerational issues about the transition to climate neutrality might help identify

where to intervene to ensure that decisions towards more sustainable urban futures are born justly and equitably. This study uses data from the European Mission on 100 Climate Neutral and

Smart Cities by 2030 and a principal component analysis to build an index of climate justice awareness. It then identifies control factors behind different levels of climate justice

awareness. The empirical analysis suggests that the more cities are engaged in climate efforts, the more they implement these efforts considering also the social justice dimension. It also

reveals that the geographical location and the relationship with higher levels of governance contribute to shape the heterogeneity in a just-considerate climate action by virtue of different

governance structures, historical legacies, and economic, cultural, and political characteristics. Overall, the analysis unveils that the availability of governmental support in capacity

building and financial advisory services, and the breadth of the city’s legal powers across different fields of action are positively related to justice awareness. Conversely, the perception

of favourable geo-climatic conditions is negatively correlated. These relationships can be read as assistance needs that cities perceive in their pathway to just climate neutrality and

highlight where future efforts in research and policy-making should focus in the following years to pave the way to a just transition. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS US CITIES

INCREASINGLY INTEGRATE JUSTICE INTO CLIMATE PLANNING AND CREATE POLICY TOOLS FOR CLIMATE JUSTICE Article Open access 30 September 2022 CLIMATE JUSTICE AND POLICY ANALYSIS: STILL A RESERVED

RELATIONSHIP Article Open access 31 July 2024 U.S. CITIES’ INTEGRATION AND EVALUATION OF EQUITY CONSIDERATIONS INTO CLIMATE ACTION PLANS Article Open access 13 September 2023 INTRODUCTION

Since before the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) was established in 1992, climate change discussions have included justice concerns. However, it is only in

recent years that the concept of climate justice has become prominent in climate academic and policy debates. We can now clearly understand climate justice as justice in relation to (i) the

responsibility for climate change and its impacts, or (ii) the effects of responses to climate change (Newell et al., 2021). We can also link it to the ‘triple injustices’ of climate change

(i.e., uneven distribution of impacts, uneven responsibility for climate change, and uneven costs associated with mitigation and adaptation (Roberts & Parks, 2015), wherein those who are

the least responsible for greenhouse gas emissions are also those who are most vulnerable to their impacts and most disadvantaged by responses to climate change (Krause, 2021). In this

study, we understand climate justice in relation to the effects of responses to climate change. Despite the academic interest in climate justice has increasingly gained momentum, several

scholars have debated on its operational value, as it might remain only normative and theoretical (Hughes & Hoffmann, 2020; Schlosberg & Collins, 2014). As an example, Brisley et al.

(2012) emphasise that there are no specific metrics available to assess the inclusion of justice dimensions in climate policies. In this study, we aim to uncover the operational value of

climate justice by evaluating justice concerns in climate decision-making processes. In particular, we build on the proposal advanced by Sovacool et al. (2017) that justice frameworks can

serve as decision-making tools that can assist planners in making policy choices capable to address both the climate change and the social justice goals. In this case, planners and

regulators are “justice aware”. However, assessing justice concerns is a challenging task, as there might be heterogeneity in how these are conceived and addressed, depending on the context

and the governance level (Chu & Cannon, 2021). Indeed, embedded in the very definition of climate justice are the pillars of territorial cohesion and multi-level governance, with

national, regional, and local actors all called upon. In this study, we focus on the local, notably urban, level. Cities are locations where developing measures against climate change is

highly urgent (Nevens & Roorda, 2014) and where opportunities for co-creation with the civil society are abundant. In particular, urban areas in the developed world account for more than

70% of energy-related global greenhouse gases from the supply side (Bellucci et al., 2012), and the share would be even higher in terms of consumption (Hoornweg et al., 2011). Additionally,

the majority of the global population lives in cities (United Nations, 2019). At the same time, there is an increasing consensus on the key role that cities can play as agents of change in

addressing global climate change (van der Heijden et al., 2019). During the late 2000s, cities began to emerge as alternative hubs for political leadership, technological advancement, and

financial support in advancing climate action (Bulkeley, 2010). They are exposed to activities, processes, or patterns, which make them the perfect loci to implement mitigation and

adaptation efforts (Diana Reckien et al., 2015). In fact, cities can be seen as “natural” sites for innovative and experimental climate action in a progressive direction (Evans et al.,

2016). Municipalities themselves recognised their key role in global climate mitigation and adaption, and committed to take concrete steps to combat the climate crisis, as announced by over

100 cities at the end of the UN’s Climate Action Summit in 2019 (Salvia et al., 2021). Further, a number of city-dedicated initiatives to deliver on the European Green Deal have been

promoted to catalyse a capillary reaction to climate change at the sub-national level, including the Covenant of Mayors—that gathers 10,000+ signatories committed to climate change

mitigation and adaptation—and the European Mission on 100 Climate-Neutral and Smart Cities (hereinafter, the Cities Mission), through which cities will pursue climate neutrality by 2030 and

will thereby design and implement ambitious climate mitigation plans while elaborating on the green, digital, and just attributes of the transition. Although these ambitious cities are ideal

contexts where both environmental and social justice goals can be achieved, due to the relatively short distance between municipalities and citizens, compared to other governance levels

(Evans, 2011), they can be hot spots of injustices, which manifest in multiple ways, including displacement, destructive redevelopments or uneven investments that may exacerbate inequalities

(Phillips et al., 2022). That is why, to express their full potential as agents of change in addressing global climate change (Bouzarovski & Haarstad, 2019), cities need to be able to

recognise the link between the planned climate efforts and their multiple implications to avoid generating or exacerbating forms of injustice (Hughes & Hoffmann, 2020). In short, cities

need to be justice-aware when developing climate action and the degree of awareness should become an indicator and a lever to guide and course-correct climate policy so that truly resilient

and future-proof urban decisions can be taken. This study aims to uncover the operational value of climate justice by providing a quantitative, ex-ante assessment of climate justice

considerations in urban climate action planning. The proposed methodology overcomes the uncertainties in terms of robustness, comparability, and interpretability of results that come with

the conceptual approaches and/or limited city samples that characterise the existing literature on the topic. Instead of qualitatively analysing a set of climate plans, we leverage the newly

collected Cities Mission dataset as an unprecedented portray of where hundreds of European cities stand in terms of climate mitigation against the background of a common and well-defined

framework and climate ambition. The dataset connects scientific and technological aspects to policy-making, risk anticipation and cross-sectoral integration to social equity, as

co-ingredients of a robust and just climate neutrality strategy, across multiple dimensions and highly diverse urban contexts. Relying on data that are elicited through a homogenous

procedure (i.e., survey), descriptive of a significant sample of respondents, and related to a well-defined climate action programme, enables us to develop a scientifically sturdy European

index of climate justice awareness. The index and its analysis are instrumental not just to compare cities and determine a Europe-wide baseline, but also to identify predictors and to

delineate the opportunity space for enhanced justice awareness. Indeed, even among the most ambitious cities in climate mitigation and adaptation, there might be considerable heterogeneity

in climate action, due to city-specific factors (Diana Reckien et al., 2015). As an example, when cities are prosperous (high GDP per capita) and populous, or when they have the financial

capacity and the know-how to implement climate action, they may engage more in climate action (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 2015; Diana Reckien et al., 2015). In contrast, when

they are constrained in their powers and boundaries, due to, e.g., regulatory limitations, cities may not express their full potential in exerting climate efforts (van der Heijden et al.,

2019). At the same time, city-specific factors might limit climate justice considerations. For instance, when cities are limited in an operational capacity, they might concentrate their

efforts towards “profitable” climate initiatives for which quantifiable emissions reductions can be demonstrated and investors can be lured, at the expenses of more socially attentive

initiatives whose benefits are less conventionally tangible (Castán Broto & Westman, 2020). In this study, we investigate these potential mechanisms and empirically address how climate

engagement, as measured by a combination of metrics of engagement, preparedness, and ambition in climate action, is related to climate justice awareness in policy-making across the

procedural, distributive, recognition, and intergenerational pillars, and which city-specific factors (such as climate, population, GDP) may serve as predictors of climate justice

considerations. To this aim, through principal component analysis (PCA), we create an index for climate action that reflects cities’ efforts in climate mitigation and adaptation strategies

and initiatives, as well as their GHG emissions reduction targets. The index is then used as an explanatory variable for a second index aimed at quantifying the level of climate justice

awareness that equally accounts for the consideration of the four justice pillars. Finally, by adopting a regression approach, we study the relationship between climate justice awareness and

climate engagement, including a set of control variables to account for local specificities and influential factors that could contribute to the different manifestations of just climate

action across European cities. THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK Cities are ideal contexts where both environmental and social justice goals can be achieved, due to the relatively short distance between

municipalities and citizens, compared to other governance levels (Evans, 2011). Despite this potential, there is evidence that, so far, city climate plans have commonly failed in embedding

social justice, resulting in an increased social divide and in disproportionate vulnerabilities to weather extremes, air pollution, and social marginalisation (Reckien et al., 2023;

Wachsmuth et al., 2016). There is a general lack of accountability for the various adverse impacts that may be triggered by climate action, notably (i) beyond wealthy districts, (ii) at the

periurban or rural fringes, and (iii) at the metropolitan/regional level (e.g., in functional urban areas). This suggests not only that the climate action at the city level needs to be

attentive to more global processes to avoid a mere displacement of injustices and unsustainable practices (Angelo & Wachsmuth, 2015, 2020), but also that cities should adopt a more

holistic approach than that based only on technical perspectives (Chu & Cannon, 2021). Against this backdrop, a body of academic work has emerged to criticise technocratic approaches,

which often prioritise regulatory, financial, and engineered interventions, while neglecting the social, cultural, and economic inequities (Meerow & Newell, 2019; Shi et al., 2016).

These critiques are particularly relevant within urban environments that are already marked by high levels of inequality, characterised by contentious issues like the marginalisation of the

vulnerable (Chu & Cannon, 2021). In this regard, scholars have observed that public policies and plans have played a key role in reinforcing systemic injustices, both directly and

indirectly (Brand and Miller, 2020). As an example, some cities that initiated measures to promote adaptation started safeguarding economically significant land from anticipated risks,

implementing exclusionary zoning and land use policies to preserve property values, and prioritising the enhancement of infrastructure and public services in affluent neighbourhoods (Long

& Rice, 2019). Consequently, scholars began to raise concerns about how these plans were contributing to displacement, perpetuating poverty, and, in certain instances, exacerbating

vulnerability to climate effects in historically marginalised communities (Anguelovski et al., 2016). A stream of research has thus emerged, to address these critiques by looking at

operationalising justice frameworks to enable climate action policy choices to address both the climate change and the social justice goals (Sovacool et al., 2017). This stream of literature

posits that when planners and regulators take into account justice dimensions from the very start of the decision-making process, then also the implementation of strategies and plans is

more likely to be able to address both the climate change and the social justice goals (Juhola et al., 2022). Practically, this calls for a need to evaluate the degree of justice awareness

in climate action planning. Despite the conceptual advancement in climate justice, however, there continues to be limited empirical evidence on how justice dimensions are actually integrated

into urban climate planning. The few exceptions, like the studies by Chu and Cannon (2021) and Juhola et al. (2022), assess the inclusion of justice dimensions in climate action plans of a

limited sample of cities by deriving interpretative justice indicators. However, this methodology and the availability of limited city samples can make it hard to extract comparable results

for large regions, like those that characterise Europe, and to derive quantitative relationships to inform decision-making. This study enriches this stream of research aiming to uncover the

operational value of climate justice by evaluating how justice concerns are taken on board in urban climate action planning. To this aim, we refer to the framework of climate justice, which

is based on environmental justice (Schlosberg & Collins, 2014). Over time, the framework of environmental justice has undergone a gradual transformation, leading to the recognition that

an inequitable distribution of environmental burdens and benefits is not inherently predetermined, but rather has underlying causes. Consequently, four dimensions crucial to achieving

justice in the context of mitigating and adapting to climate change have been commonly identified and recognised as interconnected: recognitional, distributive, procedural, and

intergenerational (Newell et al., 2021). Recognitional justice manifests in understanding differences while guaranteeing equal rights for all (Newell et al., 2021). It translates into

acknowledging the diverse needs of different societal groups in order to minimise social costs associated with climate action. This is because vulnerabilities to climate risks are

situation-dependent (Fitzgibbons & Mitchell, 2019). Understanding the significance of underlying social structures is essential for identifying the factors that contribute to social

injustices within societies, as these contribute to determine the way the most vulnerable will experience the impacts of climate change and climate action (Schlosberg, 2004). Therefore,

including recognitional justice in climate action means not only to assess whether climate action recognises and addresses varying needs across different segments of society, but also

whether it acknowledges the influence of societal structures on disadvantaged communities (Juhola et al., 2022). Equity is often understood as coterminous with distributive justice. It

refers to a state where resources, opportunities, and protection from climate hazards or risks are distributed in an equal and fair manner, regardless of the background or identity of

individuals or groups (Chu & Cannon, 2021). Climate action itself might be associated with an unequal distribution costs and benefits, and this inequality might occur both locally and

nationally (Colenbrander et al., 2018). As an example, developing a flood defence in one area may increase flood risk in downstream populations (Eriksen et al., 2021). This implies that

addressing distributive justice in climate action translates not only in estimating the climate hazards and risks, but also how these are distributed across the different social groups

(Fiack et al., 2021). Additionally, it translates in assessing which costs and benefits climate action will generate, and how these will be distributed across the social groups (Juhola et

al., 2022). Procedural justice refers to fair, accountable, and transparent processes that aim to engage all stakeholders in a non-discriminatory way (Sovacool & Dworkin, 2014). Notably,

transparent, accountable, and inclusive decision-making processes and procedures become just when they incorporate a variety of voices, values, and perspectives (Mundaca et al., 2018). This

implies that cities address procedural justice in climate action when they strive to make a variety of groups represented in as many different phases of planning process as possible, and

take on board different ideas even when this implies substantial changes (Juhola et al., 2022). Finally, climate change and climate action present a significant challenge to account for

considerations of notions of intergenerational justice. If left unchecked, it would result in an unjust burden caused by climate change (or failed climate action) placed upon future

generations by those in the present (Gonzalez-Ricoy & Rey, 2019). Intergenerational justice has renewed traction owing to the Fridays for Future movement, yet it dates back—at least—to

the report _Our Common Future_ (World Commission on Environment and Development, 1987). This report conceived sustainable development as the ability of current generations to meet their

needs without compromising that same ability of future generations (Newell et al., 2021). Therefore, urban climate action accounts for intergenerational justice concerns when future

interests are explicitly represented and taken on board (Lawrence & Köhler, 2017). DATA AND METHODS Against this theoretical framework, this study focuses on a group of particularly

ambitious cities in climate action; those that expressed interest in the Cities Mission. The Cities Mission aims to promote the transition to climate neutrality in 100+ cities by 2030. The

definition of climate neutrality standing within the Cities Mission framework requires reaching (net) zero emissions across i) all highest emitting sectors (e.g., energy, transport, waste,

industry, agriculture), ii) all emissions scopes (direct and indirect emissions within the city boundary and out-of-boundary emissions related to the disposal and treatment of

waste/wastewater generated within the city boundary), and iii) seven greenhouse gases (CO2, CH4, N2O, HFCs, PFCs, SF6, and NF3). In total, 112 cities were selected for this ambitious

programme from the 362 that participated in the call for Expression of Interest (EOI) closed on 31 January 2022. The EOI took the form of an all-encompassing questionnaire of 374 questions

designed to provide: * (i) a systematic and complete assessment of the city’s starting point (preparedness) and demonstrated engagement in climate action (engagement); * (ii) an evaluation

of the consistency, plausibility, and credibility of the commitment and capacity to reach climate neutrality by 2030 (ambition); * (iii) and a preliminary assessment of the familiarity with

integrated approaches and holistic thinking in climate action through co-benefits analysis, barriers identification, and risk anticipation. The EOI questionnaire and the data collection were

entirely designed and managed by the European Commission. Cities were given a link to access the online questionnaire. The link could be shared by the city administration to anybody in the

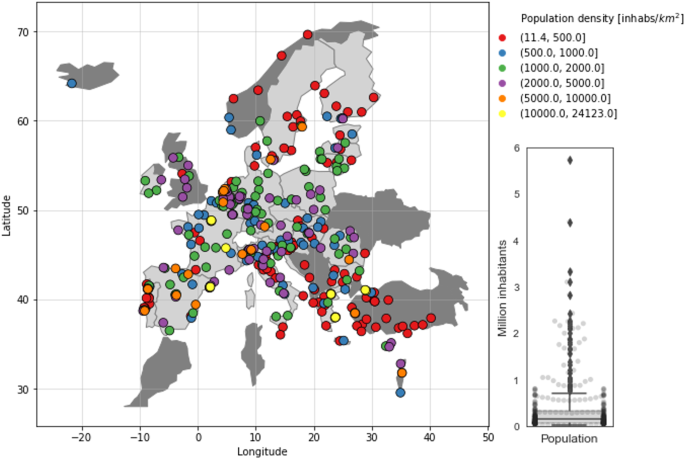

(best) position to answer the questions to ensure a compelling candidature. The analysis is based on data from all the 362 cities that answered the EOI questionnaire and thus expressed the

ambition to go emission-free in less than a decade (see Fig. 1). The sample includes cities from 35 countries encompassing all EU Member States with varied sizes, from large and medium

cities (above 50,000 inhabitants, up to 15 million inhabitants) to smaller ones (down to around 10,000 inhabitants). The starting point in climate action is also significantly diverse across

cities, with different baseline emissions, trends, and familiarity with dedicated policies and strategies (Ulpiani et al., 2023). To enable the evaluation of climate justice awareness (CJA)

and climate engagement (CE), we relied on a set of selected EOI questions (see Table 1 and for more details on the questions’ description in Table A.1 in the Supplementary Appendix),

including both multiple and single choice questions. The questions that were used to develop the climate justice awareness index were designed and selected based on the four main pillars of

climate justice (Newell et al., 2021). As _procedural_ justice concerns the various processes and elements of climate decision-making that might involve the regulation of the distribution of

goods (Walker & Day, 2012), it translates in providing access to relevant information, or legal procedures to enable to claim participation rights, recognising and acting upon unjust

procedures, and striving to address biases on the side of project proponents and/or decision-makers (Mundaca et al., 2018). Therefore, the selected questions tried to capture whether the

various key groups are usually engaged in climate planning and how. _Distributive justice_ concerns the inequalities in access to social goods and ills, like energy, water, pollution, or

food (McCauley et al., 2013; Sovacool & Dworkin, 2015; Walker & Day, 2012). In particular, one of the key aspects of distributive justice is the identification of how goods and ills

are distributed across the society (Newell et al., 2021). Hence, the selected questions capture whether cities estimate costs and benefits associated with climate action and climate change,

and whether social redistribution is considered to mitigate costs. _Recognitional justice_ is closely linked to procedural and distributive justice, being concerned with the capacity to

acknowledge the existence of different needs (energy, water, health, etc.) across the society (Walker & Day, 2012), notably the needs of the socially and politically marginalised,

including the energy poor (Della Valle & Czako, 2022). Therefore, the selected questions tried to capture whether cities acknowledge the existence of different (structurally shaped)

needs (energy, water, health, etc.) across the society. Finally, as _intergenerational justice_ concerns protecting future generations from harm, providing them with the same resources

current generations are enjoying, and with means to express their voice in climate change discussions (Sanson & Burke, 2020), the selected questions tried to capture whether future

generations’ interests are considered or represented by younger generations. Following the selection of the questions developed to reflect each of the four pillars, as many indexes were

created: (i) _recognition (RJ) (ii) distributive (DJ) (iii) procedural (PJ), and (iv) intergenerational_ justice (IJ). Notably, the replies to the sets of questions (as shown in Table 1)

were used individually to develop each of the RJ, DJ, PJ, and IJ indexes through the PCA. The answers are transformed, according to the following rules: * in case of multiple-choice

questions, a value is assigned that is equal to the total number of selected answer options. However, if the interest is in a specific answer option, 1 or 0 are assigned when the option is

or is not ticked by the city (i.e., dummy variable); * in case of single-choice questions, each answer option is weighted according to its value in terms of climate mitigation or justice

awareness (i.e., it is transformed into a numeric categorical variable). However, when only one answer option is relevant to the formulation of the corresponding index, 1 or 0 are assigned

when the option is or is not ticked by the city (i.e., dummy variable). Finally, when the answer is a number (e.g., the number of climate mitigation plans), no transformation is applied.

Table A.1 recalls the rules on a question-by-question basis and provides the original EOI questions. The PCA was deemed as an appropriate method as it enables to (i) condense multiple

variables that measure similar constructs into a smaller set of uncorrelated composite indexes, (ii) provide us with a concise set of indexes that allow for a more straightforward

explanation of the relationships between the predictors (e.g., CE) and the outcome variable (i.e., CJA) while minimising information losses, and (iii) to handle multicollinearity, which can

pose challenges in regression analysis (Shrestha, 2021). Therefore, the PCA fits well our study as we can derive indexes from multiple survey items and investigate the relationships between

these indexes and other factors, while accounting for the potential challenges that might be encountered when condensing information (i.e., loss of information) and interpreting results

(i.e., multicollinearity). This approach has also been used in previous similar studies that developed indexes related to engagement and awareness of energy issues (Martins et al., 2020).

Once derived the four justice indexes, we calculated the CJA index as a simple average of the four indexes, as we assumed that awareness of each of the four justice pillars has an equal

weight in terms of contribution to the overall climate justice awareness. Therefore, $${{{\mathrm{CJA}}}} = \frac{{RJ + DJ + PJ + IJ}}{4}$$ (1) The sixth index—the _climate engagement_ (CE)

index—was developed via PCA to capture cities’ efforts in climate action. The selected questions to develop this index tried to capture the effort in sector-specific climate mitigation

strategies and initiatives, as well as in their GHG emissions reduction targets. After creating all the indexes, a simple ordinary least squares (OLS) regression was conducted to measure the

explanatory power of the CE index and city-specific factors (population density, GDP per capita, favourable conditions, legal powers, barriers identified, and government support) on CJA

(for more details on the city-specific factors, see Table A.2 in the Supplementary Appendix). As we are analysing survey data and aim to investigate quantitative relationships, the OLS

regression model was deemed as the appropriate method, since it allows for the examination of the magnitude and direction of the relationships between the CJA (dependent variable) and the

predictor variables (CE and city-specific factors). Additionally, by enabling quantitative estimates of these relationships, it allows for numerical comparisons and for policy

recommendations (Wooldridge, 2015). All analyses were performed using Stata 15. RESULTS As described in the methods, the four justice pillar indexes and the CE index were developed via PCA

(see Table A.3 in the Supplementary Appendix for details on the PCA output, such as communalities, total variance explained, and component matrix). The quality of the produced indexes is

inferred by applying two well-established tests (Shrestha, 2021): the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) Measure of Sampling Adequacy and the Bartlett’s test. The first test returns the proportion of

variance in the variables that might be caused by underlying factors. When KMO values are higher than 0.5, the sample is deemed acceptable (Martins et al., 2020). The second test checks the

hypothesis that the correlation matrix is an identity matrix, and indicates whether the variables are unrelated and not suitable for structure detection. When the output is less than 0.05,

the available data is deemed suitable to apply the factor analysis. The Bartlett’s test reveals that the indexes are adequate, as all output values are below 0.05. The KMO corroborates the

result, with all values higher than 0.5 (see Table 2). These results confirm that the developed indexes are suitable for the analysis. Overall, across the 362 cities, the RJ index ranges

within (−1.59, 6.17) with mean −1.96 (s.d. 2.17); the PJ index ranges within (−5.98, 5.27) with mean 2.36 (s.d. 2.32); the DJ ranges within (−2.41–8.78) with mean −2.54 (s.d. 2.99); and the

IJ index ranges within (−1.20, 2.82) with mean 2.38 (s.d. 1.23). The CJA index across the 362 cities ranges within (−2.79, 5.76) with mean −6.02 (s.d. 1.88). The distribution can be

visualised in Fig. 2. As shown in Fig. 2, this index seems to vary significantly across countries, on average. To exclude issues of multicollinearity between the independent variables and

the developed CJA index that we will use in the regression analysis, we assess the Pearson’ correlation. Table 3 shows that the values are not high enough to be concerned with

multicollinearity, as all independent variables have an absolute value of Pearson correlation coefficient that is less than 0.5 (Young, 2018). This result is further corroborated by a second

test for multicollinearity using the _variance inflation factor_, developed post-regression. Table 3 also suggests the existence of a significant and strong correlation between CJA and: *

i. CE (+) * ii. Log GDP per capitaFootnote 1 (+), * iii. financial government support (+), * iv. reporting government support (+), * v. coordination government support (+), * vi. technical

government support (+), * vii. tools and skills access government support (+), * viii. dissemination government support (+), * ix. capacity government support (+), * x. regulation government

support (+), * xi. financial advisory government support (+), * xii. perceived favourable economy (+), * xiii. perceived favourable authorisation process (+), * xiv. perceived favourable

financing (+), * xv. perceived favourable communication (+), * xvi. number of fields with legal power (+), * xvii. and number of identified barriers (+). CJA is also mildly correlated with

population density (+). The regression analysis is used to confirm the strength of such relationships. Figure 3 shows the positive relationship suggested by the Pearson’s correlation between

climate engagement and climate awareness. It also shows that the average of the two indexes differs quite substantially across countries. Therefore, we first conduct the analysis using the

whole dataset. To ensure that we consider the relationships between cities within a country and take into account the shared characteristics among cities, we used cluster-robust standard

errors. This method allows for a more comprehensive understanding of the correlation structure among cities within the same country and, thus, a more valid and robust approach than standard

errors that assume independence among observations (in traditional statistical models that do not consider clustering, standard errors are assumed to be independent across all observations).

However, in the context of cities within a country, this assumption may not hold true due to similarities arising from various factors such as geographical proximity, cultural influences,

or policy interventions. Hence, we treat countries as clusters, recognising that cities within a country may have similar unobservable factors (Angrist & Pischke, 2008). Second, to

absorb any country effect and allow the estimates of the coefficients on city-level characteristics to differ across countries, we would ideally run a separate regression model for each

country (Bryan & Jenkins, 2021). However, given that countries are unevenly represented in the pool of 362 Mission cities, we resort to the category-based approach in which regressions

are computed separately on three country categories based on geographical attributes: * EASTERN: Poland, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, Belarus, Ukraine, Moldova, Romania, Bulgaria, Montenegro,

Macedonia, Albania, Kosovo, Croatia, Slovenia, Czech Republic, and Slovakia. * NORTH-WESTERNFootnote 2: Finland, Sweden, Denmark, Norway, Iceland, France, Austria, Switzerland, Germany,

Belgium, Netherlands, Luxembourg, Ireland, and the UK. * SOUTHERN: Spain, Portugal, Malta, Italy, Greece, Cyprus, Turkey, and Israel. Table 4 and Fig. 4 show the general model considering

the whole sample of cities and a category-based approach in which regressions are conducted based on countries’ categories. Results confirm a positive correlation between climate engagement

and climate justice awareness. Across all models, we find that high climate engagement seems to have a positive influence on the potential that climate decisions are made in a justice-aware

way, as the two indexes result correlated regardless of the country group. When looking at the general model, we also find that the justice-awareness potential is positively influenced by

the availability of governmental support in capacity building and in financial advisory services, and by the breadth of the fields over which the city has legal power to act/make policy

decisions. Conversely, it is negatively influenced by the perception that the city geo-climatic conditions are favourable (e.g., proximity to water bodies, moderate occurrence of climate

extremes). In North-western cities, justice awareness is positively influenced by the availability of government support in coordination and by the density of population, whereas in Southern

cities, by the extent of the city legal powers and by the availability of governmental support in financial advisory services, resource mobilisation and reporting. In Eastern cities, higher

justice awareness comes with the availability of governmental support in capacity building and in financial support, and project development/implementation. Conversely, it is negatively

influenced by the perception of a favourable climate and financial situation. Overall, all models seem to be satisfactory in explaining variability, as all _R_2 are above 0.5, and in

avoiding multicollinearity, as the mean VIF is always between 1 and 5, indicating moderate correlation between the other explanatory variables in the model, but not severe enough to require

attention. DISCUSSION Correlation analysis was conducted to examine the associations between CJA and potential drivers and barriers affecting just climate action development in a large

sample of European cities. At this stage, the focus was on identifying general influences. Out of the 18 factors tested, 17 were found to be significantly related to both climate engagement

and city-specific factors. CE exhibits a strong positive correlation (_p_ < 0.01). This result suggests that the more cities exert efforts in addressing climate change goals, the more

they are likely to take climate justice concerns on board when designing and implementing climate efforts. The following city-specific institutional and socio-economic factors were

identified as the most influential drivers of justice-awareness potential, exhibiting strong positive correlations (_p_ < 0.01): * GDP per capita and degree of city legal powers; *

government (i) financial support, (ii) reporting support, (iii) coordination support, (iv) technical assistance, (v) skill support, (vi) dissemination assistance, (vii) capacity building

assistance, (viii) policy regulation assistance, (ix) financial advisory services; * perceptions of a favourable (i) economy, (ii) financial situation, (iii) communication, and * identified

barriers to climate action. These results suggest that wealthier cities could more likely attain social justice goals when planning and implementing climate action. Cities that consider

their economic, financing, and communication strategies as favourable city-specific features are also more likely to be climate justice aware. Results also suggest that cities that receive

cross-sectoral support from higher governance levels are more likely to take into account justice dimensions. Two key drivers of CJA are also the breadth of cities legal power and the

ability to identify more barriers to climate action. Population size exhibits only a mild positive correlation (_p_ < 0.10). This suggests that being a populous city might not necessarily

lead to more justice considerations when developing climate action. Finally, perceiving climate as a favourable city-specific feature does not seem to be a motivating factor for cities to

take into account justice dimensions in climate efforts. The above correlation results are only partially confirmed by the regression analysis conducted on the whole sample of cities. Using

all factors analysed in the correlation matrix yields a model of moderate good fit. In particular, the _R_2 of 0.529 indicates that the model explains a substantial portion of the

variability in the CJA index. For CJA, CE and receiving government financial support are important factors with a strongly significant (_p_ < 0.01) contribution to the model. Notably, the

coefficient of 0.420 suggests a positive and statistically significant relationship between CE and CJA, wherein a one-unit increase in CE is associated with an estimated increase of 0.420

units in CJA, assuming all other variables in the model are held constant. This implies that cities that are more engaged in climate action tend to show higher levels of CJA. The coefficient

of 0.405 suggests a positive and statistically significant relationship between CJA and government financial support, wherein a one-unit increase in government financial support is

associated with an estimated increase of 0.405 units in CJA, ceteris paribus. This implies that cities that receive more financial support from higher governance levels tend to show higher

levels of CJA. The breadth of legal power and perceiving climate as a city-specific favourable condition are also important influencing factors of CJA, but with a lesser significance extent

(_p_ < 0.05). The coefficient of 0.0541 suggests a positive and statistically significant relationship between number of fields with legal power and CJA, wherein a one-unit increase in

the number of fields with legal power is associated with an estimated increase of 0.0541 units in CJA, ceteris paribus. This implies that cities that have the power to take decisions on a

breadth of climate-related fields tend to show higher levels of CJA. The coefficient of −0.164 suggests a negative and statistically significant relationship between favourable climate

perceptions and CJA, wherein a one-unit increase in favourable climate perceptions is associated with an estimated decrease of 0.164 units in CJA, ceteris paribus. This implies that cities

that do not perceive the urgency to act on their local climate tend to show lower levels of CJA. Finally, receiving financial advisory services from the government only mildly explains CJA.

The coefficient of 0.297 suggests a positive and statistically significant (_p_ < 0.10) relationship between financial advisory services and CJA, wherein a one-unit increase in available

financial advisory services is associated with an estimated increase of 0.297 units in CJA, assuming all other variables in the model are held constant. This implies that cities that are

equipped with more government financial advisory services tend to show higher levels of CJA. Overall, results from the general regression model suggest that CE has a positive impact on

cities' climate justice awareness, irrespective of their geographical classification. They also suggest that the availability of governmental support in capacity building and financial

advisory services, and the extent of the city legal powers across different fields of action are positively related to justice awareness. This suggests that when cities have the means and

freedom to decide how to plan and implement climate efforts, they can also pursue objectives that are not immediately related to emission reduction, but embrace a broader dimension sensitive

to social justice. At the same time, results suggest that the perception of favourable geo-climatic conditions is negatively related to climate justice awareness. This insight further

echoes the positive relationship between CE and CJA, as a favourable climate might reduce the perceived urgency of climate action and the consideration of the social issues associated with

it. The results from the regression analyses run on specific geographic groups highlight that when country effects are taken into account, the relationships with CJA estimated with the

general model are not always confirmed. Additionally, they unveil relationships with new dimensions. This suggests that aggregating data can make certain relationships only apparently strong

(Wooldridge, 2015), and that the fact that cities within the same geographic region might share similar governance structures, historical legacies, and economic, cultural, and political

characteristics (Breil et al., 2018) needs to be accounted in the analysis. For all geographical groups, the regression model yields a moderate good fit since the _R_2 (0.524 for

North-Western cities, 0.537 for Southern cities, and 0.609 for Eastern cities) indicates that the model explains a substantial portion of the variability in the CJA index. As observed in the

general model, we find that for CJA, CE is a key factor with a strongly significant (_p_ < 0.01) contribution to the model, with the following territorial nuances. The coefficients

(0.526, 0.350, and 0.413 for the three groups respectively) suggest a positive and statistically significant relationship between CE and CJA, wherein a one-unit increase in CE is associated

with an estimated increase of 0.526, 0.350, and 0.413 units in CJA (and thus 0.106 more or 0.07 and 0.007 units less than estimated in the general model, respectively). When it comes to

North-Western cities in particular, differently from the general model we find that population density and receiving coordination support from the government moderately (_p_ < 0.05)

explain CJA. Notably, the coefficient of 0.0000880 suggests a positive and statistically significant relationship between population density and CJA, wherein a one-unit increase in

population density is associated with an estimated increase of 0.0000880 units in CJA. This implies that densely populated North-Western cities tend to show higher levels of CJA. Further,

the coefficient of 0.662 suggests a positive and statistically significant relationship between receiving coordination support from the government and CJA, wherein a one-unit increase in

government coordination support is associated with an estimated increase of 0.662 units in CJA. This entails that North-Western cities that receive higher coordination support from the

government tend to show higher levels of CJA. Overall, the regression analysis for North-western cities reveals that CJA is positively influenced by the availability of governmental support

in coordination and by population density. This suggests that the provision of support in coordination can be a key way to address the potential high structural complexity (level of

alignment and interaction across different governance and low population density) undermining the attention North-western cities can devote to social objectives when planning and

implementing climate action. This finding aligns with existing evidence on the higher emissions mitigation ambition demonstrated by Northern and Western Europe cities (Reckien et al., 2018;

Reckien et al., 2015; Salvia et al., 2021) and with the significant correlation between such ambition and national incentives, characteristics, and climate policies (Hsu et al., 2020; Salvia

et al., 2021). Similar to the general model, among Southern cities, receiving financial advisory services from the government and the breadth of legal power explain CJA, and these

relationships are stronger (_p_ < 0.01) than for the general model. The coefficient of 0.642 suggests that a one-unit increase in available financial advisory services is associated with

an estimated increase of 0.642 units in CJA, ceteris paribus. This implies that Southern cities that are equipped with more government financial advisory services tend to show higher levels

of CJA. The coefficient of 0.112 suggests that a one-unit increase in the number of fields with legal power is associated with an estimated increase of 0.112 units in CJA, ceteris paribus.

This implies that the more Southern cities have the power to decide where to exert their climate effort, the more they tend to show higher levels of CJA. Finally, differently from the

general model, we find that receiving government support on reporting moderately (_p_ < 0.10) explains CJA. Notably, the coefficient of 0.521 suggests a positive and statistically

significant relationship between government support on reporting and CJA, wherein a one-unit increase in government support on reporting is associated with an estimated increase of 0.521

units in CJA. This entails that Southern cities that are equipped with tools that ease coordination tend to show higher levels of CJA. Overall, for Southern cities, results highlight that

CJA is positively influenced by the breadth of the city legal powers and by the availability of governmental support in financial advice and resource mobilisation, and mildly in reporting.

This suggests that providing more legitimacy and advice on how to get resources for climate action by higher-level governments can be a key way to make Southern cities more considerate of

social objectives in their climate efforts. Finally, for Eastern cities and in agreement with the general model, we find that perceiving own climate as a favourable local feature explains

CJA, and this relationship is stronger (_p_ < 0.05) than for the general model. The coefficient of −0.183 suggests that a one-unit increase in perceptions of a favourable climate is

associated with an estimated decrease of 0.183 units in CJA, ceteris paribus. This implies that Eastern cities that perceive a lesser urgency to act on their local climate tend to show lower

levels of CJA. Further, differently from the general model, we find that receiving government financial support strongly (_p_ < 0.01) explains CJA, and perceiving financial conditions as

favourable local features moderately (_p_ < 0.10) does so. The coefficient of 0.637 suggests that a one-unit increase in government financial support is associated with an estimated

increase of 0.637 units in CJA, ceteris paribus. This entails that Eastern cities that receive financial support are more prone to consider justice dimensions. The coefficient of −0.340

suggests that a one-unit increase in perceptions of favourable financial conditions is associated with an estimated decrease of 0.340 units in CJA, ceteris paribus. This complements the

previous result, suggesting that cities that are eligible for financial support are more prone to consider justice dimensions. Overall, the regression analysis on Eastern cities reveals that

climate justice awareness is positively influenced by the availability of governmental support in capacity building, financial support, and project development/implementation, while it is

negatively influenced by the perception of a favourable climate and mildly, financial situation. This suggests that equipping Eastern cities with additional means and resources can be a key

way to ease the consideration of justice dimensions. Conversely, the result that cities get socially detached when feeling secure (in terms of climate and financial risks) points to a need

to address security misperceptions and empowerment. Indeed, there is evidence that Southern and Eastern cities—particularly those ranking low in terms of capacity/GDP—tend to be less

ambitious in climate mitigation and to rely on exogenous systems (international climate networks, national government) to steer their climate action (Salvia et al., 2021). This may entail

that for these cities, external forces define their capacity to co-tackle climate justice. With respect to policy implications, in Northern cities, where economic development and low

population density might increase the complexity of decision-making, support in coordination might ease the consideration of social objectives in climate action. Being more advanced in their

adaptation policies, and having a longer tradition of citizen engagement (Breil et al., 2018), most North-western cities are focused on abating the hardest emissions (i.e., the last

percentage points), hence a high degree of coordination needs to be in place to remove residual barriers (e.g., complex jurisdictions, unfavourable regulations). Southern cities, which are

at higher risks from negative social and environmental consequences of climate change (Mavromatidi et al., 2018), reveal a good potential to implement a social just climate action, but this

needs to be unlocked through empowerment measures. In Eastern cities, where paths defined by institutional and historical legacies might still dictate an infrastructural and economic divide

(Ürge-Vorsatz et al., 2018), more immediate objectives might take over the consideration of social objectives, unless cities receive dedicated external support. CONCLUSIONS Cities can be key

agents of change in addressing global climate change, being “natural” sites for innovative and experimental climate action in a progressive direction. Cities themselves acknowledged this

role in Europe, as testified by the European Mission on 100 Climate-Neutral and Smart Cities, where 100+ cities committed to pursue climate neutrality by 2030. However, even among the most

ambitious cities in climate mitigation, there might be considerable heterogeneity in the scope of climate action. In particular, cities can be loci of injustices, if they are not able to

recognise how planned climate efforts might generate or exacerbate forms of injustice in their specific contexts. That is why, cities need to be justice-aware when developing climate action.

Climate justice has increasingly gained momentum in the academic and policy debates on climate change; however, many have also debated its operational value. The few investigations on the

topic are based on a limited number of cities and interpretative indicators. The main contribution of this study lies in empirically uncovering the operational value of climate justice in

urban climate action, by evaluating climate justice concerns in urban climate decision-making processes and by identifying key areas that could lead to better consideration of justice

dimensions across European cities. We demonstrate, via econometric analysis, a way to homogenously evaluate the degree of justice awareness in climate action planning, and to use this

measure as a lever to guide and course-correct city-level climate policy to simultaneously pursue the climate change and social justice goals. Drawing from the climate justice framework and

a unique dataset comprising responses homogenously elicited through a survey, we created an indicator for climate justice awareness and assessed how this can be predicted by climate

engagement and a set of city-specific factors. In particular, we used the data from 362 cities who expressed interest in the Cities Mission, and used a PCA approach to develop a climate

justice awareness index inclusive of the procedural, distributive, recognition, and intergenerational justice pillars. Correlation and regression results reveal that, regardless of the

geographical categorisation, cities’ climate justice awareness is positively influenced by climate engagement. This empirical evidence, new to the current literature, provides some

implications for practice, as it shows that cities that are more engaged in addressing climate change goals tend to design and implement their efforts by co-targeting social justice goals.

Moreover, our results offer additional novel insights into how some city-specific factors might act as drivers and barriers to justice-considerate climate action. Overall and for the first

time to the best of the authors’ knowledge, this study sheds light on the positive relationship that exists between engagement in climate action at the city level and awareness of its social

justice aspects, evaluated across its recognitional, distributive, procedural, and intergenerational dimensions. Embedding justice considerations into climate action planning implies

additional challenges and a higher degree of integration and holism in urban planning and policy-making. This is mirrored in the predictors for higher justice awareness levels and is nuanced

according to specific national characteristics. The insights gathered through this analysis constitute a solid baseline to improve our understanding of the drivers and barriers to a just

climate transition. They can legitimate and inform ongoing climate mitigation frameworks at an international and European scale, such as the UN-backed Race to Zero campaign, that rally

non-State actors to take rigorous and immediate action to reduce global emissions and deliver a healthier, fairer zero-carbon world in time. As engagement in climate efforts tends to

co-stimulate social justice goals, ongoing and future climate agendas could capitalise on the results here presented to maximise the synergistic effect and to leverage the territorial,

economic, and socio-political predictors. However, it is important to note that correlation and regression analysis alone cannot establish causal relationships. Therefore, an avenue for

future research is to undertake comprehensive analyses to delve deeper into the associations uncovered in this study. Future research could also involve exploring how each of the four

climate justice pillars are understood by urban decision-makers and citizens by engaging in interviews with them. Such efforts would contribute to the development of comprehensive climate

justice awareness indices that incorporate better the characteristics of cities. Finally, we analysed a particular subgroup of ambitious cities in climate action, at the stage of formulating

a vision to climate neutrality in the short haul. Future studies should investigate the planned and implemented efforts of the 100+ selected cities, by assessing how climate justice is

factually integrated in their actions. Furthermore, as the Cities Mission proceeds in its implementation phase, new knowledge and experience will be generated on how to deliver just

transformations within and beyond the city boundary. A fully fledged just transition builds on values of territorial cohesion and multi-level governance to legitimise the target and multiply

the benefits. Hence, best practices in multi-scale action and in tackling Scope 3/consumption-based emissions will be collected and guidelines will be disseminated through the Mission in

the attempt to eradicate “low-carbon illusions” and establish a paradigm of full climate responsibility. As cities acknowledged in the EOI that non-compliance with the principle of equal

opportunities on all levels throughout the transition will undermine its achievement, it is expected that the Mission will catalyse the conceptualisation, testing, and spread of new

transition models to expand the frontiers of climate justice across local-to-global networks of production, consumption, and distribution. DATA AVAILABILITY The datasets generated and

analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to confidentiality agreements. NOTES * We take the log of GDP per capita to reduce the right skewness of GDP per capita

(values of GDP per capita are skewed around left tail). Another reason is that GDP per capita is better considered on a multiplicative rather than additive scale (€1000 is worth a lot more

to a vulnerable than a rich because €1000 is a much greater fraction of the poor person’s wealth) * Northern and Western cities have been pooled together as Northern cities were only 33;

therefore, this number was not sufficient to conduct a separate regression model. REFERENCES * Angelo H, Wachsmuth D (2015) Urbanizing urban political ecology: a critique of methodological

cityism. Int J Urban Region Res 39(1):16–27 Article Google Scholar * Angelo H, Wachsmuth D (2020) Why does everyone think cities can save the planet? Urban Stud 57(11):2201–2221 Article

Google Scholar * Angrist JD, Pischke JS (2008) Mostly harmless econometrics: an empiricist’s companion. In: Mostly harmless econometrics: an empiricist’s companion. Princeton University

Press * Anguelovski I, Shi L, Chu E, Gallagher D, Goh K, Lamb Z, Reeve K, Teicher H (2016) Equity impacts of urban land use planning for climate adaptation: critical perspectives from the

global North and South. J Plann Educ Res 36(3). https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X16645166 * Bellucci F, Bogner JE, Sturchio NC (2012) Greenhouse gas emissions at the urban scale. Elements,

8(6). https://doi.org/10.2113/gselements.8.6.445 * Bouzarovski S, Haarstad H (2019) Rescaling low-carbon transformations: towards a relational ontology. Trans Inst Br Geogr 44(2).

https://doi.org/10.1111/tran.12275 * Brand AL, Charles M (2020) Tomorrow I’ll be at the table: Black geographies and urban planning: Areview of the literature. J Plan Lit 35(4):460–474

Article Google Scholar * Breil M, Downing C, Kazmierczak A, Mäkinen K, Romanovska L, Terämä E, Swart RJ (2018) Social vulnerability to climate change in European cities–state of play in

policy and Practice (ETC/CCA Technical Paper; No. 2018/1), EEA–European Environment Agency * Brisley R, Welstead J, Hindle R, Paavola J (2012) Socially just adaptation to climate change.

Joseph Roundtree Foundation, York, UK * Bryan ML, Jenkins SP (2021) Regression analysis of country effects using multilevel data: a cautionary tale. SSRN Electron J.

https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2322088 * Bulkeley H (2010) Cities and the governing of climate change. Ann Rev Environ Resour 35. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-environ-072809-101747 * Castán

Broto V, Westman LK (2020). Ten years after Copenhagen: reimagining climate change governance in urban areas. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Clim Change. 11(4). https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.643 * Chu

EK, Cannon CE (2021) Equity, inclusion, and justice as criteria for decision-making on climate adaptation in cities. Curr Opin Environ Sustain. 51

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2021.02.009 * Colenbrander S, Dodman D, Mitlin D (2018) Using climate finance to advance climate justice: the politics and practice of channelling resources

to the local level. Clim Policy, 18(7). https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2017.1388212 * Della Valle N, Czako V (2022) Empowering energy citizenship among the energy poor. Energy Res Soc Sci

89(C):102654 Google Scholar * Eriksen S, Schipper ELF, Scoville-Simonds M, Vincent K, Adam HN, Brooks N, Harding B, Khatri D, Lenaerts L, Liverman D, Mills-Novoa M, Mosberg M, Movik S, Muok

B, Nightingale A, Ojha H, Sygna L, Taylor M, Vogel C, West JJ (2021) Adaptation interventions and their effect on vulnerability in developing countries: help, hindrance or irrelevance?

World Dev 141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105383 * Eurostat (2023) Statistics explained—glossary: country codes. Eurostat * Evans J, Karvonen A, Raven R (2016) The experimental

city. Routledge * Evans JP (2011) Resilience, ecology and adaptation in the experimental city. Trans Inst Br Geogr 36(2). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-5661.2010.00420.x * Fiack D,

Cumberbatch J, Sutherland M, Zerphey N (2021) Sustainable adaptation: Social equity and local climate adaptation planning in U.S cities. Cities 115:103235.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2021.103235 Article Google Scholar * Fitzgibbons J, Mitchell C (2019). Just urban futures? Exploring equity in “100 resilient cities.” World Dev 122.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2019.06.021 * Gonzalez-Ricoy I, Rey F (2019) Enfranchising the future: climate justice and the representation of future generations. Wiley Interdiscip Rev

Clim Change. 10(5). https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.598 * Hoornweg D, Sugar L, Gómez CLT (2011) Cities and greenhouse gas emissions: moving forward. Environ Urban 23(1).

https://doi.org/10.1177/0956247810392270 * Hsu A, Tan J, Ng YM, Toh W, Vanda R, Goyal N (2020) Performance determinants show European cities are delivering on climate mitigation. Nat Clim

Change 10(11):1015–1022. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-020-0879-9 Article ADS Google Scholar * Hughes S, Hoffmann M (2020) Just urban transitions: toward a research agenda. In: Wiley

Interdiscip Rev Clim Change 11(3). https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.640 * Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (2015) Human settlements, infrastructure, and spatial planning. In: Climate

Change 2014: Mitigation of Climate Change. Cambridge University Press * Juhola S, Heikkinen M, Pietilä T, Groundstroem F, Käyhkö J (2022) Connecting climate justice and adaptation planning:

an adaptation justice index. Environ Sci Policy, 136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2022.07.024 * Krause D (2021) Transformative approaches to address climate change and achieve climate

justice. In: Routledge handbook of climate justice. Routledge * Lawrence P, Köhler L (2017) Representation of future generations through international climate litigation: a normative

framework. German Yearbook of International Law, 60. https://doi.org/10.3790/gyil.60.1.639 * Long J, Rice JL (2019) From sustainable urbanism to climate urbanism. Urban Stud 56(5).

https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098018770846 * Martins A, Madaleno M, Dias MF (2020). Energy literacy assessment among Portuguese university members: Knowledge, attitude, and behavior. Energy

Rep 6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egyr.2020.11.117 * Mavromatidi A, Briche E, Claeys C (2018). Mapping and analyzing socio-environmental vulnerability to coastal hazards induced by climate

change: an application to coastal Mediterranean cities in France. Cities, 72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2017.08.007 * McCauley DA, Heffron RJ, Stephan H, Jenkins K (2013) Advancing

energy justice: the triumvirate of tenets. Int Energy Law Rev 32(3):107–110 Google Scholar * Meerow S, Newell JP (2019) Urban resilience for whom, what, when, where, and why? Urban Geogr

40(3). https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2016.1206395 * Mundaca L, Busch H, Schwer S (2018) ‘Successful’ low-carbon energy transitions at the community level? An energy justice perspective.

Appl Energy 218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2018.02.146 * Nevens F, Roorda C (2014). A climate of change: a transition approach for climate neutrality in the city of Ghent (Belgium).

Sustain Cities Soc 10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2013.06.001 * Newell P, Srivastava S, Naess LO, Torres Contreras GA, Price R (2021) Toward transformative climate justice: an emerging

research agenda. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Clim Change 12(6). https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.733 * Phillips J, Bouzarovski S, Boamah F, Fuller S, Furlong K, Knuth S, Mould I, Thomson H, Zheng W

(2022) Just transitions in cities and regions: a global agenda. British Academy Working Paper * Reckien D, Salvia M, Heidrich O, Church JM, Pietrapertosa F, De Gregorio-Hurtado S, D’Alonzo

V, Foley A, Simoes SG, Krkoška Lorencová E, Orru H, Orru K, Wejs A, Flacke J, Olazabal M, Geneletti D, Feliu E, Vasilie S, Nador C, Dawson R (2018) How are cities planning to respond to

climate change? Assessment of local climate plans from 885 cities in the EU-28. J Clean Prod 191:207–219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.03.220 Article Google Scholar * Reckien

Diana, Buzasi A, Olazabal M, Spyridaki N-A, Eckersley P, Simoes SG, Salvia M, Pietrapertosa F, Fokaides P, Goonesekera SM, Tardieu L, Balzan MV, de Boer CL, De Gregorio Hurtado S, Feliu E,

Flamos A, Foley A, Geneletti D, Grafakos S, Wejs A (2023) Quality of urban climate adaptation plans over time. Npj Urban Sustain 3(1):13. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42949-023-00085-1 Article

Google Scholar * Reckien D, Flacke J, Olazabal M, Heidrich O (2015) The influence of drivers and barriers on urban adaptation and mitigation plans-an empirical analysis of European Cities.

PLoS ONE 10(8). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0135597 * Roberts JT, Parks BC (2015) A climate of injustice: global inequality, north-south politics, and climate policy. In: Global

environmental accord (vol. 1). The MIT Press * Salvia M, Reckien D, Pietrapertosa F, Eckersley P, Spyridaki NA, Krook-Riekkola A, Olazabal M, De Gregorio Hurtado S, Simoes SG, Geneletti D,

Viguié V, Fokaides PA, Ioannou BI, Flamos A, Csete MS, Buzasi A, Orru H, de Boer C, Foley A, … Heidrich O (2021). Will climate mitigation ambitions lead to carbon neutrality? An analysis of

the local-level plans of 327 cities in the EU. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2020.110253 * Sanson AV, Burke SEL (2020). Climate change and children: an issue

of intergenerational justice. In: Children and peace. Springer https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-22176-8_21 * Schlosberg D (2004) Reconceiving environmental justice: global movements and

political theories. Environ Polit 13(3). https://doi.org/10.1080/0964401042000229025 * Schlosberg D, Collins LB (2014). From environmental to climate justice: climate change and the

discourse of environmental justice. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Clim Change 5(3). https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.275 * Shi L, Chu E, Anguelovski I, Aylett A, Debats J, Goh K, Schenk T, Seto KC,

Dodman D, Roberts D, Roberts JT, Van Deveer SD (2016) Roadmap towards justice in urban climate adaptation research. Nat Clim Change 6(2). https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate2841 * Shrestha N

(2021) Factor analysis as a tool for survey analysis. Am J Appl Math Stat 9(1). https://doi.org/10.12691/ajams-9-1-2 * Sovacool BK, Burke M, Baker L, Kotikalapudi CK, Wlokas H (2017) New

frontiers and conceptual frameworks for energy justice. Energy Policy 105:677–691 Article Google Scholar * Sovacool BK, Dworkin MH (2014) Global energy justice: problems, principles, and

practices. Cambridge University Press * Sovacool BK, Dworkin MH (2015) Energy justice: {Conceptual} insights and practical applications. Appl Energy 142:435–444 Article Google Scholar *

Ulpiani G, Vetters N, Melica G, Bertoldi P (2023). Towards the first cohort of climate-neutral cities: expected impact, current gaps, and next steps to take to establish evidence-based

zero-emission urban futures. Sustain Cities Soc 95(104572). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2023.104572 * United Nations (2019) World urbanization prospects - population division. In United

Nations * Ürge-Vorsatz D, Rosenzweig C, Dawson RJ, Sanchez Rodriguez R, Bai X, Barau AS, Seto KC, Dhakal S (2018) Locking in positive climate responses in cities. Nat Clim Change

8(3):174–177 Article ADS Google Scholar * van der Heijden J, Patterson J, Juhola S, Wolfram M (2019). Special section: advancing the role of cities in climate governance–promise, limits,

politics. J Environ Plann Manage 62(3). https://doi.org/10.1080/09640568.2018.1513832 * Wachsmuth D, Cohen DA, Angelo H (2016) Expand the frontiers of urban sustainability. Nature

536(7617):391–393. https://doi.org/10.1038/536391a Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Walker G, Day R (2012) Fuel poverty as injustice: Integrating distribution, recognition and

procedure in the struggle for affordable warmth. Energy Policy, 49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2012.01.044 * Wooldridge JM (2015) Introductory econometrics: {A} modern approach. Nelson

Education * World Commission on Environment and Development (1987) Our common future: report of the World Commission on Environment and Development. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK *

Young DS (2018) Handbook of regression methods. In: Handbook of regression methods. Routledge and CRC Press Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The views expressed here are purely those of

the authors and may not, under any circumstances, be regarded as an official position of the European Commission. The authors warmly than Pietro Florio (Joint Research Centre, European

Commission) for extracting georeferenced GDP data used to characterise the cities. AUTHOR INFORMATION AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * European Commission, Joint Research Centre, Ispra, Italy

Nives Della Valle & Giulia Ulpiani * European Commission, Joint Research Centre, Brussels, Belgium Nadja Vetters Authors * Nives Della Valle View author publications You can also search

for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Giulia Ulpiani View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Nadja Vetters View author publications You can

also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CONTRIBUTIONS NDV: conceptualisation, formal analysis, visualisation, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review editing. GU:

conceptualization, data collection, visualisation, writing—review editing. NV: writing—review editing. CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to Nives Della Valle. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING

INTERESTS The authors declare no competing interests. ETHICS DECLARATIONS Local and regional research relevant to the field of study has been taken into account in the references. ETHICS

APPROVAL This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors. INFORMED CONSENT This article does not contain any studies with human participants

performed by any of the authors. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION PUBLISHER’S NOTE Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional

affiliations. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION APPENDIX RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS OPEN ACCESS This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits

use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the

Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated

otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds

the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Reprints and

permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Della Valle, N., Ulpiani, G. & Vetters, N. Assessing climate justice awareness among climate neutral-to-be cities. _Humanit Soc Sci

Commun_ 10, 440 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01953-y Download citation * Received: 10 March 2023 * Accepted: 18 July 2023 * Published: 26 July 2023 * DOI:

https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01953-y SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not

currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative