Play all audios:

ABSTRACT The morpho-functional properties of neural networks constantly adapt in response to environmental stimuli. The olfactory bulb is particularly prone to constant reshaping of neural

networks because of ongoing neurogenesis. It remains unclear whether the complexity of distinct odor-induced learning paradigms and sensory stimulation induces different forms of structural

plasticity. In the present study, we automatically reconstructed spines in 3D from confocal images and performed unsupervised clustering based on morphometric features. We show that while

sensory deprivation decreased the spine density of adult-born neurons without affecting the morphometric properties of these spines, simple and complex odor learning paradigms triggered

distinct forms of structural plasticity. A simple odor learning task affected the morphometric properties of the spines, whereas a complex odor learning task induced changes in spine

density. Our work reveals distinct forms of structural plasticity in the olfactory bulb tailored to the complexity of odor-learning paradigms and sensory inputs. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED

BY OTHERS RESOLVING DIFFERENT PRESYNAPTIC ACTIVITY PATTERNS WITHIN SINGLE OLFACTORY GLOMERULI OF _XENOPUS LAEVIS_ LARVAE Article Open access 09 July 2021 SEX DIFFERENCES IN DENDRITIC SPINE

DENSITY AND MORPHOLOGY IN AUDITORY AND VISUAL CORTICES IN ADOLESCENCE AND ADULTHOOD Article Open access 10 June 2020 IMMATURE OLFACTORY SENSORY NEURONS PROVIDE BEHAVIOURALLY RELEVANT SENSORY

INPUT TO THE OLFACTORY BULB Article Open access 19 October 2022 INTRODUCTION During the early postnatal period, the developing brain is shaped and remodeled in response to environmental

stimuli. The major changes that occur during these critical periods of development, which are marked by a high level of plasticity, are activity-dependent structural modifications when some

synaptic connections are reinforced and maintained while others are eliminated1. This increased level of remodeling in response to environmental stimuli is attenuated in the mature brain

when the critical period ends, except for adult neurogenic regions such as the olfactory bulb (OB) and dentate gyrus, which receive new neurons throughout the lifespan of animals2,3. The OB

is the first relay of olfactory information processing and is an excellent model for studying how various types of structural modifications are triggered in response to environmental stimuli

and learning and how these changes allow for the adaptation of bulbar network functioning and animal behavior. In the OB, the two main populations of interneurons, granule and

periglomerular cells (GCs and PGs), are constantly renewed through the process of adult neurogenesis2. GCs establish a particular form of connection with the principal cells of the OB,

mitral and tufted cells, through reciprocal dendrodendritic synapses. The inhibition of principal cells by GCs is crucial for olfactory information processing and olfactory behavior2. In

addition to being renewed, GCs also exhibit a high level of structural plasticity that persists after their full morpho-functional maturation4. In fact, ~20% of fully mature GC dendritic

spines are constantly being added/removed from the OB circuitry5. This persistent structural plasticity optimizes odor information processing in the adult OB5 and is modulated by odor

learning6,7 and sensory activity8,9. Indeed, it has been shown that odor learning induces an increase in the spine density of GCs6,7 while sensory deprivation decreases the spine

density8,9,10. Moreover, in vivo imaging studies have revealed that another type of structural plasticity involving the relocation of mature spines allows for the rapid adaptation of the OB

circuitry to changes in the olfactory environment4,5,11. This process has been shown to be specific to mature adult-born GCs5,11,12, which are known to play a unique role in OB functioning

compared to their early-born counterparts. Notably, during their integration into the OB neuronal network, two- to three-week-old adult-born OB neurons go through a phase when they are more

responsive to new odorants and have broader responsiveness to individual odorants13,14. Adult-born GCs also play an important role in a wide range of social and spontaneous olfactory

behaviors as well as odor learning and memory15. Specifically, these cells play a major role in learning an odor discrimination task16,17,18, a task that also induces an increase in the

spine density of this population of cells6,7. Although all these studies highlight changes in spine density, it remains unclear whether the morphometric parameters of spines also change with

the level of olfactory stimuli and/or learning. This is particularly relevant given that the size of a spine head is correlated with the surface of the postsynaptic density (PSD) as well as

synaptic strength, whereas both the length and width of a spine neck are linked to postsynaptic potential19,20,21,22,23. Historically, dendritic spines have been manually classified into a

few groups, such as stubby, mushroom, or thin, based on their morphological features, which helps simplify data interpretation24,25. However, clustering, an unsupervised learning technique,

has emerged as a promising alternative for the analysis of dendritic spines. Clustering groups of spines based on inherent similarities without predefined categories can reveal unknown spine

subtypes of functional or pathological relevance, capture continuous variations in spine morphology, and reduce subjectivity and bias in classification25,26,27. By providing a more nuanced

and objective perspective on spine diversity, based on various morphometric parameters, clustering can enhance our understanding of neuronal function and dysfunction and capture how specific

properties of spines are affected by sensory inputs and/or learning and memory28,29. To assess how sensory activity and odor learning of different complexities affect the structural

plasticity of adult-born GCs in the OB, we developed a computational pipeline to extract dendritic spines from confocal images and performed cluster analyses of reconstructed dendritic

spines based on distinct morphometric features. We discovered an unexpected diversity of structural plasticity of adult-born GCs in response to the level of sensory activities and odor

learning of different complexities. Sensory deprivation decreased spine density without any changes in the morphometric properties of the remaining spines or in spine clusters.

Interestingly, while complex odor learning increased spine density without any substantial modifications in the morphometric properties of spines, simple odor learning tasks, on the other

hand, did not affect spine density but led to the enlargement of remaining spines. Our data reveal that a distinct mode of structural plasticity might be engaged in adult-born GCs to adapt

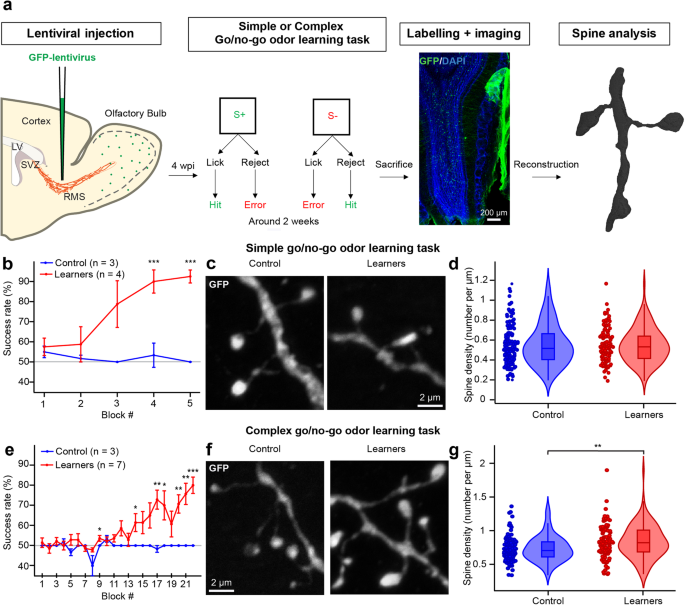

the functioning of the bulbar network in response to the level of sensory input and complexity of odor learning paradigms. RESULTS GO/NO-GO ODOR DISCRIMINATION LEARNING TASKS OF DIFFERENT

COMPLEXITIES LEAD TO DISTINCT CHANGES IN THE SPINE DENSITY OF ADULT-BORN GCS We first investigated the impact of odor learning tasks of different complexity on the structural plasticity of

adult-born GCs. Approximately 4 weeks following an injection of a GFP-encoding lentivirus into the rostral migratory stream (RMS) (Fig. 1a), mice were trained on a go/no-go olfactory

discrimination task and depending on the complexity of the task, different mixes of odors were presented (Fig. 1a). In the simple version of the task, the mice had to discriminate between

two dissimilar odorants: 1% octanal as S+ vs. 1% decanal as S-. Animals from the learner group (_n_ = 4 mice) received a water reward if the odor was discriminated correctly. Animals from

the control group (_n_ = 3 mice) were exposed to the same conditions but received a reward regardless of the odor. The learner group reached the criterion of 80% of correct responses in 5

blocks over the course of 1 day (Fig. 1b) and after only three blocks, the success rate of the learner group was significantly different from that of the control group (Student _t_-test, _p_

< _0.001_). Following the learning test, the mice were perfused, and high-resolution confocal images of adult-born GCs were acquired (Fig. 1c). We first quantified the spine density on

the distal dendrites of adult-born GCs in the external plexiform layer, the site of contact between GCs and bulbar principal neurons. Our quantification did not reveal any significant

difference in spine density between the control and go/no-go simple learning groups (0.55 ± 0.21 spines/µm for the control group, _n_ = 110 cells from 3 mice vs. 0.55 ± 0.17 spines/µm for

the simple learner group, _n_ = 111 cells from 3 mice, _p_ = 0.82 Fig. 1d). Another group of animals was trained with a complex version of the go/no-go task involving very similar odor

mixtures: 0.6% limonene(+) and 0.4% limonene(−) as S+ vs. 0.4% limonene(+) and 0.6% limonene(−) as S-. The learner group (_n_ = 7 mice) reached the criterion of 80% of correct responses

after 22 blocks, while the control group, as expected, never reached this criterion. The difference between the learner and control groups in terms of success rate was highly significant

after block 13 (Fig. 1e, significant _p_ values: 0.047, 0.043, 0.002, 0.032, 0.004, 0.003, <0.001 for blocks 9, 14, 17, 18, 20, 21, 22 respectively) Interestingly, the assessment of the

spine density of adult-born GCs revealed that, unlike the simple discrimination task, the complex task led to an increase in spine density after training (control group: 0.73 ± 0.19

spines/µm, _n_ = 97 cells from 4 mice vs. learner group: 0.84 ± 0.25 spines/µm, _n_ = 104 cells from 4 mice, _p_ = 0.001 with the Student _t_-test, Fig. 1f, g). These data suggest that the

spine density of GCs is differently affected depending on the complexity of the go/no-go learning task. We also observed that the spine density of GCs from mice of a control group undergoing

the complex go/no-go task was higher than the spine density of cells from the control group undergoing the go/no-go simple task (0.55 ± 0.21 spines/µm vs. 0.73 ± 0.19 spines/µm for the

simple and complex go/no-go control groups, respectively, _p_ < 0.001 with the Student _t_-test) (Figs. 1d, e). As the mice in the complex go/no-go control group were exposed to odors in

an operant conditioning task for a much longer period of time and encountered odors of a more complex nature, these data suggest that the duration of olfactory stimulation and the complexity

of the odors used might affect the spine density of adult-born GCs. These results are in line with previous observations showing that a lack of odor stimulation decreases the spine density

of adult-born GCs11,30. ODOR DEPRIVATION DECREASES THE SPINE DENSITY OF ADULT-BORN GCS We next investigated the impact of decreased levels of olfactory stimulation on the structural

plasticity of adult-born GCs. To do so, 14 days following the injection of a GFP-expressing lentivirus into the RMS, we performed a unilateral nostril occlusion to deprive an OB hemisphere

of odor stimulation. We used the contralateral OB hemisphere as a control. Following 14 days of sensory deprivation, we performed a quantitative assessment of the spine density of adult-born

GCs. To ensure the effectiveness of the sensory deprivation, we assessed the level of tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) expression, which is known to be regulated in an activity-dependent manner9,

in the glomerular layer of the odor-deprived OB hemisphere compared to the control. We observed a characteristic 55.67 ± 13.05% decrease in TH expression in the glomerular layer of

odor-deprived OB (Fig. 2a), which is in line with previous reports11,30. Moreover, and in accordance with previous reports9,11,30, sensory deprivation resulted in a statistically significant

decrease in the spine density of adult-born GCs in the odor-deprived OB hemisphere compared to the control OB hemisphere (control OB: 0.55 ± 0.19 spines/µm, _n_ = 52 cells from 3 mice vs.

occluded OB: 0.44 ± 0.12 spines/µm, _n_ = 50 cells from 3 mice, _p_ < 0.001 with an unpaired Student _t_-test; Fig. 2b, c). Our results showed that the level of sensory activity in the OB

influenced the plasticity of adult-born GCs by modulating their spine density. A PIPELINE TO PERFORM QUANTITATIVE ANALYSES OF 3D-RECONSTRUCTED DENDRITIC SPINES FROM CONFOCAL IMAGES Our

results show that the spine density of adult-born GCs could be differently affected by odor learning tasks of different complexity and sensory stimulation. However, sensory stimulation and

learning may induce changes not only in the number of spines but may also affect the morphometric properties of existing spines. We thus developed a pipeline that starts with the

3D-reconstruction of spines, followed by an assessment of up to 10 distinct morphometric parameters, dimension reduction, and cluster analysis. High resolution confocal images of dendritic

spines from animals from the different experimental conditions were first obtained (Fig. 3a). The images were deconvolved using the DAMAS algorithm31,32, followed by segmentation with the

morphological snake Chan-Vese algorithm33,34,35,36. Lastly, a marching cube algorithm was used to reconstruct the mesh37,38. We extracted 4936 spines using the selection tool of Meshlab. For

each extracted spine, ten features were calculated: Length, Surface, Volume, Average Distance, Open Angle, Hull Volume, Hull Ratio, Coefficient of Variation in Distance (CVD), Mean

Curvature, and Mean Gaussian Curvature (Fig. 3b). To ensure the integrity of our dendritic spine morphology in the reconstruction process, we conducted a comparative analysis between the

spine lengths measured via expert blind assessment and those derived automatically through our reconstruction pipeline. A linear regression analysis yielded a coefficient (_R_2) of 0.9477,

indicating a robust correlation between the manually measured and the pipeline-calculated lengths. This high degree of correlation suggests that our pipeline does not significantly alter the

morphology of the dendritic spines (Supplementary Fig. 1a). A covariance analysis was performed to find the correlation between the features and to only keep the least correlated ones

(Supplementary Fig. 1e). Correlations ranging from 0.7 to 0.89 were considered strong, while correlations ranging from 0.9 to 1 were considered very strong based on the literature39. A very

strong correlation was discovered between Length and Average Distance (0.97). For further analyses, we selected the Length parameter because it is a widely accepted and used feature. The

Surface, Volume, and Hull Volume parameters also showed very strong correlations (0.98 between Surface and Volume, 0.97 between Surface and Hull Volume, and 0.99 between Volume and Hull

Volume). Of those three parameters, we selected Surface as it is a widely used feature in morphometric assessments of dendritic spines. Lastly, the Hull Ratio, CVD, and Open Angle were

retained because they were not correlated with any other feature. We next applied a Standard Scaler followed by a dimension reduction with a Principal Component Analysis (PCA) (Fig. 3c).

This led to three Principal Components (PCs) representing 85.4% of the total variance of the data (Supplementary Fig. 1b). Spines from the three experiments were included (go/no-go simple

task, go/no-go complex task, and sensory deprivation), together with their respective controls. The resulting representation of the dendritic spines was homogenous, with no obvious clusters

(Fig. 3d, e, f). Based on the analysis of the directionality of the coefficients of the linear combination (PCA loadings), PC1 was mostly composed of Surface, Length, and CVD, PC2 was

composed of Surface and Open Angle, and, lastly, PC3 was mostly related to the Hull Ratio. The extracted features could then be used for further analyses such as clustering. ADULT-BORN GC

SPINES CAN BE ASSEMBLED INTO DIFFERENT CLUSTERS BASED ON EXPERIMENTAL CONDITIONS Dendritic spines are highly dynamic, and these protrusions constantly change in size and shape in response to

the sensory environment. As there is a continuum of spine shapes and sizes40, which can also be seen in our dataset after dimension reduction, any attempt to classify spines based on their

shape using arbitrary categories could be erroneous27. As such, an automatic clustering approach is preferable. In such an approach, the number of clusters is the first parameter that needs

to be determined. We identified the appropriate number of clusters for our spine dataset using three different scores: the Elbow score, the Silhouette score, and the Calinski-Harabsz score

(Fig. 4a and Supplementary Fig. 1c, d). All three scores suggested that five clusters were present in the dataset. Consequently, we applied a K-Means clustering algorithm with 5 clusters.

The result of this algorithm lead to the following clusters. Cluster 1 (_n_ = 1160 spines) was located on the low value of the first principal component (mean PC1 = –1.683). Cluster 2 (_n_ =

790 spines) was located on the high value of the first principal component (mean PC1 = 2.146). Cluster 3 (n = 628 spines) was located in the middle of the first principal component (mean

PC1 = 0.551), but with a high PC2 value (mean=1.866). Cluster 4 (n = 1610 spines) was located at the low value of PC3 (mean = –0.860) and cluster 5 (_n_ = 748 spines) was located at the high

value of PC3 (mean=1.095) and the low value of PC2 (mean = –1.224) (Fig. 4b). An assessment of the reconstructed spines in each cluster made it possible to associate the mean value of each

feature to the morphology of the spine (Fig. 4c). Cluster 1 was mainly composed of small stubby spines or small mushrooms, with a short length (1.39 ± 0.31 μm), small surface area (8.24 ±

4.03 μm2), small CVD (0.28 ± 0.08), and particularly high Open Angle (0.94 ± 0.11). Cluster 2 was composed of long mushrooms with a long length (3.59 ± 0.81 μm), high CVD (0.45 ± 0.07), and

very high surface area (19.35 ± 6.65 μm2). Cluster 3 was composed of spines with a large surface area (26.17 ± 9.18 μm2). However, these spines were generally shorter than the spines in

cluster 2 (2.55 ± 0.51 μm) and had a higher Open Angle (1.01 ± 0.16). Clusters 4 and 5 had similar spines, with similar lengths (1.89 ± 0.31 μm and 2.07 ± 0.52 μm, respectively), similar

surface areas (9.36 ± 4.16 and 8.42 ± 3.88, respectively), similar Open Angles (0.69 ± 0.16 and 0.66 ± 0.17, respectively), and similar CVDs (0.41 ± 0.05 and 0.451 ± 0.05, respectively).

However, the spines of cluster 5 were more elongated with higher Hull Ratio (0.85 ± 0.20 vs. 0.40 ± 0.11 for clusters 5 and 4, respectively) which, for these spines, reflect a lower volume

as compared to spines of cluster 4. The clustering of dendritic spines of adult-born GCs based on their morphometric features allowed us to determine whether spines from one or several

clusters were morphologically altered in response to a simple or complex go/no-go odor learning task and to sensory deprivation. SENSORY DEPRIVATION DOES NOT AFFECT SPINE MORPHOLOGY Our

results, as well as those from previous reports11,30, indicate that sensory deprivation led to a decrease in the spine density of adult-born GCs. It remains unknown, however, whether sensory

deprivation also changes the morphometric properties of the remaining spines. To address this issue, we compared the morphometric features of GC spines in the occluded odor-deprived group

(_n_ = 370 spines) to those of GC spines in the control group (_n_ = 457 spines). We observed no significant differences in any of the morphometric properties of GC spines between the

odor-deprived and control groups (Fig. 5a). Cohen’s term d (effect size index) showed a very small to small effect for every variable. After clustering, no differences in cluster

distribution were seen with the Agresti-Caffo test (Fig. 5b). The most prevalent clusters of spines were clusters 4 and 5, which contained similar spines. These spines were relatively small

with thin-like spines that represented 50.4% and 56% of the total spines for the control and occluded groups, respectively. Spines with a high surface area (clusters 2 and 3) had a

representation of 31.5% and 28.4% for the control and occluded groups, respectively. To ensure that there were no changes in morphologies within the cluster, we compared the occluded and

control groups for each cluster. No differences were seen in spine morphologies for any cluster (Fig. 5c). This result suggests that sensory deprivation via nostril occlusion only affected

the spine density of adult-born GCs, with no changes in the morphometric properties of the remaining spines. DIFFERENT TYPES OF PLASTICITY ARE EVOKED BY LEARNING, DEPENDING ON THE COMPLEXITY

OF THE GO/NO-GO TASK Given the distinct effect on spine density of adult-born GCs in the control groups of go/no-go simple and complex odor learning tasks, we determined whether the

complexity of the operant task also influenced the morphology of dendritic spines. We compared spines from both the simple (_n_ = 1334 spines) and complex task (_n_ = 832 spines) control

groups. Interestingly, we observed major differences between spines from both control groups. Cohen’s term’ size effect test reported a very small to small effect for every variable. When

both control groups were compared, significant differences were found with respect to spine surfaces (13.37 ± 8.90 μm2 vs. 10.95 ± 7.16 μm2 for the simple and complex task control groups,

respectively; _p_ < 0.001 with the Student _t_-test), Hull Ratio (simple task control group: 0.60 ± 0.21 vs. 0.50 ± 0.19 for the simple and complex task control groups, respectively; _p_

< 0.001 with the Student _t_-test), CVD (0.41 ± 0.09 vs. 0.36 ± 0.09 for the simple and complex task control groups, respectively; _p_ < 0.001 with the Student _t_-test), and Open

Angle (0.85 ± 0.19 vs. 0.64 ± 0.19 for the simple and complex task control groups, respectively; _p_ < 0.001 with the Student _t_-test, Supplementary Fig. 2a). No difference was observed

with respect to spine length. The cluster distribution between the two control groups was also different. There were significantly more spines with cluster 2 (Agresti-Caffo, _p_ < 0.001)

and cluster 4 (Agresti-Caffo, _p_ < 0.001) in the control group of the complex go/no-go task, which concomitantly resulted in fewer spines with a cluster 3 morphology (Agresti-Caffo, _p_

< 0.001) and a cluster 5 morphology (Agresti-Caffo, _p_ < 0.001) (Supplementary Fig. 2b). The KDE map shows that the distribution of the spine morphology remains consistent between the

two control groups (Supplementary Fig. 2c). The duration of the odor stimulation in the go/no-go task and the complexity of the odor used thus had an impact on the morphology of the

dendritic spines, even when no association between a particular odorant and a reward was involved. We next determined whether learning a go/no-go simple task that did not induce any changes

in the spine density of adult-born GCs affected the morphometric properties of spines. The morphometric properties of spines from the learner group of the simple go/no-go task (_n_ = 767

spines from 111 cells, 3 mice) were compared to those of the control group (_n_ = 1334 spines from 119 cells, 3 mice). Cohen’s term _d_ was calculated and indicated a very small to small

effect for every variable. Significant differences (Fig. 6a) were found for four features between the control and learner groups: Surface, with 13.37 ± 9.0 μm2 and 16.19 ± 10.40 μm2 (_p_

< 0.001 with the Student _t_-test) for the control and learner groups, respectively, Hull Ratio, with 0.6 ± 0.21 and 0.57 ± 0.20 (_p_ = 0.005 with the Student _t_-test) for the control

and learner groups, respectively, CVD, with 0.41 ± 0.09 and 0.4 ± 0.09 (_p_ = 0.001 with the Student _t_-test) for the control and learner groups, respectively, and Open Angle, with 0.85 ±

0.19 and 0.93 ± 0.18 (_p_ < 0.001 with the Student _t_-test) for the control and learner groups, respectively. No significant changes were observed in spine length between the two groups.

These results indicate that while spine length was not affected by the simple go/no-go learning task, this learning paradigm led to larger spines, as attested to by changes in the Surface,

Hull Ratio, CVD, and Open Angle. The changes in morphology were also significant with respect to the distribution of several clusters (Fig. 6b). Following learning, the proportion of spines

in cluster 2 decreased from 14.6% in the control group to 8.74% in the learner group (Agresti-Caffo, _p_ < 0.001). Similarly, the spines of cluster 5 decreased from 17.9% in the control

group to 14% in the learner group (Agresti-Caffo, _p_ = 0.017). The proportion of spines in cluster 3 increased from 17.7% in the control group to 31% in the learner group (Agresti-Caffo,

_p_ < 0.001). Overall, learning to associate the simple odor with a water reward in go/no-go odor discrimination task led to the appearance of more spines with a mushroom-like shape as

seen by an increase in the Surface and Open Angle and a reduction in the Hull Ratio and CVD. To ascertain that each cluster in both groups were represented by spines of similar morphologies,

the spines of each cluster in the control group were compared to those of the learner go/no-go group. No differences were seen in spine morphologies within any cluster (Fig. 6c). To

understand the morphological changes between clusters, Kernel Density Estimation (KDE) was used to map the spine densities of clusters 2, 5, and 3 as well as PC1 and PC2 (Fig. 6d). After

learning, spines from cluster 2, which are represented by long mushrooms, and spines from cluster 5, which are represented by thin spines with complex structures, tended to move toward

cluster 3. These observations thus implied that spines from clusters 2 and 5, but not spines from clusters 1 and 4, tended to change their morphology toward that of spines from cluster 3,

i.e., mushroom-like spines with large surfaces. As complex go/no-go odor discrimination tasks resulted in an increase in spine density (Fig. 1g), we next determined whether this task also

induced changes in spine morphology. The control group (_n_ = 832 spines from 99 cells, 4 mice) was compared to the learner group (_n_ = 1175 spines from 112 cells, 4 mice) that performed

the complex go/no-go task. Interestingly, no significant differences (Fig. 7a) were found for any of the morphometric features. Cohen’s term _d_ reported a very small to small effect for

every variable. We observed only a slight change in the distribution of clusters (Fig. 7b) with the population of cluster 5 increasing (Agresti-Caffo, _p_ = 0.020) between the control

(9.38%) and the learner (12.7%) groups. The spines in cluster 3, which are mushroom-like spines with large surface areas, were particularly underrepresented, with only 2.52% and 2.55% in the

control and learner groups, respectively. However, cluster 4, which contains thin spines with no complex shapes, constituted 42.5% of the control group and 41.1% of the learner group. To

ascertain whether the clusters were represented by spines with the same morphologies, we compared the control and learner go/no-go groups for each cluster. No differences were observed in

spine morphologies within any cluster (Fig. 7c). To understand the changes in morphologies, KDE maps of spine densities for clusters 2, 3, and 5 were computed (Fig. 7d). The differences in

the distribution of spines in cluster 3 and cluster 2 were not significant between the control and learner groups. There were significant differences between the control and learner groups

for the spines in cluster 5 that tended to change their morphology in the opposite direction to cluster 3, which could explain the low representation of spines in cluster 3 and the high

number of spines with a cluster 5 morphology. This is in contrast to the changes observed in the simple go/no learning task when the spines belonging to cluster 5 tended towards cluster 3.

Overall, our data indicate that, depending on the level of sensory stimulation and the complexity of the odor learning paradigms, distinct forms of structural plasticity of adult-born GCs

might be involved in adapting the functioning of the bulbar network. Sensory deprivation decreased spine density, with no changes in spine morphology. The simple go/no-go odor learning task

led to changes in the morphometric properties of existing spines without any modifications in spine density. On the other hand, the complex go/no-go learning task increased spine density,

with only subtle changes in the morphometric properties of spines. The present study thus shows that there was a vast panoply of distinct forms of structural modifications in the bulbar

network. DISCUSSION In the present work we show that the spines of adult-born GCs exhibited different modes of structural plasticity in response to the level of sensory activity and the

complexities of odor learning tasks. The computational pipeline we developed enabled us to divide the reconstructed spines into five distinct clusters based on various morphometric

properties and to assess how the level of sensory stimulation or odor learning affected the morphology and type of spines. The analysis of the cluster distribution of spines from various

conditions together with the comparison of KDE maps highlighted the spines movement dynamics over the landscape of their shapes induced, or not, by olfactory stimulation and learning. We

show that sensory deprivation led to a uniform reduction in spine density, with no changes in the morphology of the spines or their distribution in the different clusters. The difficulty of

a go/no-go odor learning task determined whether the structural plasticity of adult-born GCs was reflected by changes in the morphometric properties of the spines or spine density. In fact,

while a simple odor discrimination task affected the morphology of the spines, the complex odor learning task resulted in a higher spine density, with no substantial differences in the

clusters distribution. Why are such distinct types of structural plasticity of adult-born GCs engaged in response to the level of sensory input and the complexity of odor learning tasks?

While further work is required to understand what the functional properties of each spine cluster of adult-born GCs are and how each cluster is involved in odor information processing, it is

conceivable that the type of structural plasticity of adult-born GCs is tailored to the needs of the bulbar network in order to adjust its functioning to changing environmental conditions

and learned experiences. Sensory deprivation led to an overall reduction in spine density. While these data are consistent with previous reports11,30, it was unknown how the morphometric

properties of the remaining spines are affected. Our computational pipeline and clustering analysis show that sensory deprivation did not lead to any changes in the morphometric properties

of spines and the clusters. GCs synchronize the activities of principal OB neurons through their dendro-dendritic reciprocal synapses, which allows odor information to be processed in the

bulbar network41,42. Adult-born neurons may synchronize the activities of new assemblies of principal neurons involved in new memory16,43,44,45. The global reduction in odor-induced activity

through unilateral nostril occlusion may not require the synchronization of new assemblies of principal cells because of the lack of sensory inputs. The OB operational neuronal network may

thus be maintained through other mechanisms, with no additional structural plasticity required by GC spines. Indeed, it has been shown that sensory deprivation affects not only the output

synapses of GCs, as evidenced by the decrease in spine density, but also induces an increase in the input synapses onto GCs10. Furthermore, sensory deprivation also triggers an increase in

the excitability of newborn GCs, leading to an increase in action potential-dependent GABA release and unaltered synchronized activity of principal cells46. These studies highlight the

adaptive responses in the OB network and indicate that increases in excitability and input synapses onto adult-born GCs maintain the functioning of the neuronal network with no additional

need for changes in the morphometric properties of GC spines. On the other hand, depending on the complexity of the olfactory learning task, the structural plasticity of adult-born GCs is

manifested either by changes in the morphometric properties of spines and/or by increases in spine density. The simple go/no-go odor task depended on the presentation of two distinct odors

that mice were able to learn very quickly, i.e., in 5 blocks over the course of 1 day. This contrasts with the complex go/no-go learning task based on discrimination between two very similar

odor mixtures, which took the mice 22 blocks over multiple days to learn. Our data suggest that learning a simple odor discrimination task might be achieved by enlarging the pre-existing

spines of adult-born GCs without forming new ones. In contrast, the complex odor discrimination task required the formation and stabilization of additional spines of adult-born GCs that

might be necessary for synchronizing the activities of new principal cell assemblies. These data are in line with previous reports showing that there is an increase in the spine density of

adult-born but not pre-existing GCs during a complex odor learning task6,7. Interestingly, this increase is driven by inputs from the piriform cortex6,7. Optogenetic stimulation of these

projections strengthens learning-induced plasticity7, while their inactivation impedes learning-induced changes6. It remains largely unknown how a simple odor learning task affects the

feedback projections onto the OB and whether the changes in spine morphologies observed during this task are driven locally in the bulbar network or are mediated by centrifugal projections

from other brain regions. It is conceivable that, depending on the complexity of the odor learning task, distinct brain regions or different levels of feedback are required to associate the

water reward with odor stimuli and trigger distinct types of structural plasticity. In line with this, it has been shown that different types of odor-associative learning tasks may induce

distinct patterns of early immediate gene expression in the orbital and infralimbic cortices47, which are known to be involved in odor memory48. Future experiments based on mapping the

activated neuronal assemblies across the brain regions during simple and complex go/no-go odor learning tasks will be required to address this issue. The reconstruction of dendritic spines

in three dimensions made it possible to obtain more morphometric information than analyses of 2D images of spines. The most relevant features were Length, Surface, Hull Ratio, CVD, and Open

Angle, followed by PCA, which reduced the number of dimensions. As spine shapes form a continuum and cannot be categorized49, the clustering was performed on dendritic spines based on

different morphometric properties. When the spines in each cluster were examined, a general characteristic for each cluster could be determined. Cluster 1 predominantly consisted of small

stubby spines, cluster 2 of long mushroom spines, cluster 3 of mushroom spines with a larger surface area, and clusters 4 and 5 of long thin spines distinguished by a higher Hull Ratio for

cluster 5. The Open Angle appeared to be a highly effective indicator for distinguishing between mushroom and stubby spines, with the mean value being larger for the stubby spines. The CVD

was particularly high for mushroom spines because of their distinct morphology, which is comprised of a head and a neck. The Hull Ratio represents elongated spines with a lower volume.

Although all these parameters allowed us to cluster spines based on their morphometric properties, our KDE map representation of spine clusters also made it possible to highlight clusters

that were particularly sensitive to odor learning and, at the same time, determine the transition of clusters from one to another within their continuum. Spines in cluster 1 were

particularly stable and did not undergo any modifications in response to sensory deprivation or to a simple or complex odor learning task. This contrasts with spines in the other clusters

that were modified by learning to different degrees. Although the simple odor learning task induced changes in clusters 2, 3, and 5, the KDE map representation shows that spines in clusters

2 and 5 changed their morphology toward the morphology of spines in cluster 3. Clusters 2 and 5 consisted of mushroom spines with smaller surface areas and long thin spines, respectively,

whereas cluster 3 harbored mushroom spines with a larger surface area. The transition of clusters 2 and 5 to cluster 3 indicated that these spines became bigger in response to a simple

go/no-go odor learning task. The larger spines are usually associated with a larger PSD, which might lead to increased synaptic efficacy. It should be mentioned, however, that the spines of

GCs are constituents of dendro-dendritic reciprocal synapses, which implies that the same spine contains post-synaptic glutamatergic and pre-synaptic GABAergic parts. It is currently unclear

whether the increased surface area reflects changes in both the pre- and post-synaptic constituents and what functional outcome is induced by these changes. Interestingly, while the complex

odor learning task largely resulted in changes in spine density, the subtle morphometric modifications observed after this learning task were opposite to those of the simple go/no-go task.

Our cluster analysis and KDE map representation show that there was an increase in spines in cluster 5 while the spines in the cluster 3 were particularly under-represented in both the

control (2.52%) and learner (2.55%) groups. The spines in cluster 5 tended to change their morphology in a direction opposite to cluster 3, unlike with the simple go/no-go learning task

where they changed their morphology toward cluster 3. As the complex go/no-go odor learning task led to an increase in spine density, this might reflect the addition of new spines. If this

is the case, it would indicate that a complex odor learning task leads to the formation and stabilization of new spines that predominantly belong to cluster 5. On the other hand, sensory

deprivation decreased spine density with no noticeable changes in the spine clusters, indicating that the decrease was rather homogenous across the various clusters. At the first sight, the

homogenous decrease in the density of spines across the various clusters seem at odds with our previous results showing that spines with spine head filopodia-like protrusions (SHF) are

selectively preserved after sensory deprivation11. This can be explained by the fact that, first, SHF are very motile and appear and disappear very rapidly within a few minutes11. They can

be easily observed in time-lapse imaging studies. However, due to their rapid dynamics, they are under-represented in the fixed tissue that we used for our current analysis. Second, SHF were

also very thin and were more difficult to reconstruct with our pipeline. Future studies to perform 3D reconstruction and clustering analyses of spines derived from in vivo two-photon

imaging studies in the OB, as we did previously11, combined with further improvements to the 3D reconstruction pipeline, will help address this issue. In addition to learning-induced changes

in the morphometric properties of spines and/or their density, our observations of marked changes in the morphology of the spines of the two control groups performing simple and complex

tasks without associating the odor with a water reward (i.e., learning) were intriguing. Almost all the clusters, except cluster 1, were affected. Clusters exhibiting larger changes included

cluster 3, which decreased from 17.7% following the simple odor task to 2.17% following the complex go/no-go task, and cluster 4, which showed opposite changes (24.5% following the simple

odor go/no-go task vs. 42.5% following the complex go/no-go task). The almost complete disappearance of cluster 3, which was central to the simple odor learning-induced changes, following

the go/no-go complex task highlighted once again the different levels of structural modification of adult-born GCs in response to environmental challenges. This also indicates that the

structural plasticity of adult-born GCs might be triggered not only in response to odor learning but also in response to the difficulty of the operating task, the duration of the odor

stimulation, or the complexity of the odor mixtures. Future studies to test the role of passive exposure of mice to complex odor mixtures without exposing them to the go/no-go operational

task will help resolve these issues. One of the limitations of our study was that we tailored our 3D reconstruction and computational pipeline to confocal images. We selected this approach

given that confocal microscopy is widely used and enables the rapid testing and adaptation of our pipeline to user-specific needs. However, confocal microscopy does not provide sufficient

resolution to resolve intricate details of spine morphology. Super-resolution microscopy, such as stimulated emission depletion (STED) microscopy, has recently shown that only a few, if any,

stubby spines can be observed in organotypic slices of the hippocampus23. It is thus possible that because of lower resolution of confocal microscopy as compared to STED, both small stubby

and small mushroom spines were regrouped in the cluster 1 using our analytical pipeline. It should be mentioned, however, that independent of the type of spines in cluster 1, our clustering

analysis based on various morphometric properties, automatically derived from the reconstructed dendritic spines without imposing any specific criteria related to the spine’s neck or head,

showed that all the spines in this cluster had distinctive characteristics compared to the other clusters. Another limitation of our study was the lack of functional and ultrastructural

signatures of clustered spines. Future studies using electron microscopic analyses of spines in a particular cluster and a functional assessment of their properties by combined glutamate

uncaging and Ca2+ imaging will provide a better understanding of the functions of the spines in each specific cluster and how they are involved in the functioning of the bulbar network.

Lastly, it should be noted that GCs are a very heterogenous population of neurons that are characterized by the expression of distinct neurochemical markers and spatio-temporal assignments

in the bulbar network12,50,51. Each GC subtype may be involved in a different odor behavior51. In the present study, we did not determine whether learning or sensory stimulation-associated

changes in spine density and morphometric properties were linked to specific neurochemical signatures of adult-born GCs. Future studies that combine genetic targeting of different subtypes

of adult-born GCs and computational assessments of learning-induced morphometric changes in spines will help address these issues. Although all these limitations will pave the way path for

future studies that will broaden our understanding of the structuro-functional properties of spines, the present study revealed that there is a vast panoply of distinct types of structural

plasticity in adult-born GCs that are tailored in response to environmental stimuli and learning experiences. METHODS ANIMALS Adult (>2-month-old) male C57BL/6 mice (Charles River) were

used for all experiments. The experiments were performed in accordance with Canadian Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals guidelines and were approved by the Animal Protection

Committee of Université Laval. The mice were kept in groups of 4–5 on a 12-h light/dark cycle in a temperature-controlled facility (22 °C), with food and water ad libitum. The animals that

underwent the go/no-go odor discrimination procedure were partially water-deprived, individually housed, and kept on a reverse light-dark cycle for 7–10 days before beginning the

experiments. Animals were randomly assigned to the various experimental groups. STEREOTAXIC SURGERIES We used a GFP-expressing lentiviral vector (LV-EF1α-puro, SignaGen Laboratories,

SL100269) to label neuronal precursors and image GC dendritic spines. Mice were stereotaxically injected in the RMS under isoflurane anesthesia (2–2.5% isoflurane, 1 L/min of oxygen) and

were kept on a heating pad during the entire surgical procedure. The following coordinates (with respect to the bregma) were used to target the RMS: anterior-posterior (AP) 2.55,

medio-lateral (ML) 0.82, and dorso-ventral (DV) 3.15. The mice were allowed to recover on a heating blanket in a clean cage before returning to the housing room. SENSORY DEPRIVATION Two

weeks after the viral injections, a group of animals was unilaterally sensory deprived. Occlusion tubes were made using polyethylene tubing (PE50, I.D. 0.58 mm, O.D. 0.965 mm; Becton

Dickinson), with the center blocked using a tight-fitting Vicryl suture knot (3–0; Johnson & Johnson). The 5-mm-long petroleum jelly-coated plugs were inserted in the left nostril of the

mice under isoflurane anesthesia, according to the procedure described previously11,52,53. The mice were sacrificed by intracardiac perfusion 14 days later (i.e., 4 weeks post-viral

injection). GO/NO-GO OLFACTORY DISCRIMINATION LEARNING Approximately 4–5 weeks after the injection of the GFP-expressing lentivirus, the mice were partially water-deprived to reach 80–85% of

their initial body weight prior to starting the go/no-go training. They first underwent training sessions to habituate themselves to the olfactometer chamber and learn how to get a water

reward. The mice were trained using 20 trials, with no exposure to an odor, to insert their snouts into the odor sampling port and lick the water port to receive a 3-µL water reward. The two

ports were located side-by-side. The reward-associated odor (S+) was then introduced. Inserting the snout into the odor sampling port broke a light beam and opened an odor valve. The

duration of the opening was increased gradually from 0.1 to 1 s over several sessions, and mice with a minimum sampling time of 50 ms were given a water reward. The mice usually completed

this training after one or two 30 min sessions. Once they had successfully completed this training step, they were subjected to the go/no-go odor discrimination test. Prior to being

introduced to the non-reinforced odor (S-), the mice underwent an introductory S- session consisting of exposure to S+ for 30 trials. If the success rate was at least 80%, the discrimination

task was begun. The mice were then exposed randomly to S+ or S-, and the percentage of correct responses was calculated for each block of 20 trials. If a mouse licked the water port after

being exposed to S+ (hit) and did not lick the water port after being exposed to S- (correct rejection), this was recorded as a correct response. A false response was recorded if the mouse

licked the water port after being exposed to S- or if it did not lick the water port after being exposed to S+. A mouse was considered successful if it reached a criterion score of 80%. The

control group underwent the same go/no-go procedure but received the water reward independently of the odor used (S+ or S-). Mice from both groups underwent one of the two versions of the

task. The simple task involved 0.1% octanal (Sigma Aldrich) diluted in 99.9% mineral oil (Sigma Aldrich) as S+ and 0.1% decanal as S-. The complex version of the task involved two mixtures

of similar odorants: 0.6% (+)-limonene (Sigma Aldrich) + 0.4% (−)-limonene (Sigma Aldrich) (S+) diluted in 99.9% mineral oil vs. 0.4% (+)-limonene, + 0.6% (−)-limonene (S−) diluted in 99.9%

mineral oil. The mice from the two groups were sacrificed by intracardiac perfusion 1 h after completing the task. IMMUNOHISTOCHEMISTRY The mice were deeply anesthetized using an

intraperitoneal injection of sodium pentobarbital (12 mg/mL; 0.1 mL per 10 g of body weight) and were intracardially perfused with 0.9% NaCl followed by 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA). The brains

were collected and were post-fixed overnight in 4% PFA. Horizontal 100-μm-thick OB sections were cut using a vibratome (Leica) and were incubated overnight with a chicken anti-GFP primary

antibody (Aves Labs, GFP-1020, 1:1000) diluted in 1% PBS supplemented with 0.5% Triton X-100 and 4% milk. For animals that underwent the sensory deprivation procedure, some slices were

incubated overnight with a mouse anti-tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) primary antibody (Immunostar, ref. 22941, 1:1000) to compare deprived and control OBs. TH labeling is commonly used to assess

sensory deprivation efficiency, with occlusion resulting in a 50% decrease in the TH signal in the ipsilateral hemisphere9. The corresponding secondary antibodies were then used.

Fluorescence images were acquired using an inverted Zeiss microscope (LSM 700, AxioObserver) with a 63X oil immersion objective (Plan Apochromat, NA: 1.4). To optimize image acquisition, we

used a resolution of 1024 × 1024 pixels with pixels of size 0.05 μm × 0.05 μm and an optical sectioning of 0.35 μm. Confocal microscopy was chosen because it is a widely used technique to

visualize spines. For reproducibility purposes and for the robustness of the analysis, the same imaging parameters were used for the entire study. DENDRITIC AND DENDRITIC SPINE

RECONSTRUCTIONS First, animals and experiments were anonymized to avoid any bias during extraction. Confocal images of GC spines collected from the different experimental groups were

pre-processed with the DAMAS deconvolution algorithm31,32 using the Iterative Deconvolve 3D plugin in ImageJ 1.53c54. The adapted DAMAS algorithm begins with a standard beamforming approach,

utilizing the intensity of the pixels in the image. Then, in an iterative process, regions with the lowest intensity are progressively removed, and beamforming is recalculated at each step.

This method leads to a robust deconvolution that enhances image clarity and detail. The images were then segmented using a Morphological Active Contours without Edges algorithm34,35,36 with

the convergence set at 100 iterations and the parameter µ set at 1, which influences the smoothing and depends on the complexity of the segmented object. The other two parameters, λ1 and

λ2, were set at 1 and 9, respectively, as these parameters are related to the ratio between intensity and background. These parameters were determined empirically to increase the

signal-to-noise ratio but were kept the same for all images. After segmentation, some images had visual artifacts in the form of single black pixels (value = 0) and were removed with a

python script. In this script, for each black pixel, if the pixel was surrounded by at least 8 pixels with a value >0, the value of the black pixel was set as the mean of the surrounding

pixels. The processed images were converted into meshes using the marching cubes algorithm37,38. The spacing used in the algorithm was 0.24, 0.05, 0.05, which corresponds to the pixel size

for axes z, x, and y. The z axis was corrected for spherical aberration55. A polygonal mesh was generated using triangles to reproduce the surface of the spine. Each triangle was composed of

vertices and was connected by edges. Before extracting the spines, a custom optimization process was performed using the following steps: a box was created around the mesh. Then, the target

length was determined using the diagonal of this mesh box. Subsequently, a decision was made regarding the target level of detail, with ‘normal’ being the chosen setting. This was followed

by the removal of degenerated triangles, specifically those that were collinear. The process also involved eliminating isolated vertices that were not connected to any face or edge. Then,

the removal of self-intersecting edges and faces, as well as the elimination of duplicated faces. Isolated vertices were then removed a second time. To ensure there were no reconstruction

issues with the mesh, the outer hull volume was calculated. The process continued with the removal of obtuse triangles, those with an angle greater than 179 degrees. Another round of

removing duplicated faces and vertices was conducted. Finally, the integrity of the mesh was assessed. In cases where the mesh was found to be broken, the entire process was restarted from

the third step, albeit using a lower level of detail. After this reconstruction, the spines were extracted manually from the dendrite using Meshlab software56. MEASUREMENT OF MORPHOMETRIC

FEATURES To measure the morphometric features of the reconstructed spines, the hole left from the separation of the spine from the dendrite was used to calculate the position of the spine

base center (Sbc). Graph theory was used to assess the number of neighbors of each vertex. Because the vertices with the lowest number of neighbors were closest to the spine base with only

three neighbors, the spine base center can be defined as the mean coordinate of these vertices. LENGTH (L) The Length between each vertex (N) of the mesh in three dimensions (x, y, z) and

the spine base center (Sbc) is first calculated: $$\vec{{l}_{i}}=\left({x}_{i}-{S}_{b{c}_{x}},{y}_{i}-{S}_{b{c}_{y}},{z}_{i}-{S}_{b{c}_{z}}\right)$$ Then, a new mathematical subset is

defined with the 5% longest distance (_n_). The final length is determined as the mean of these lengths: $$L=1/n\mathop{\sum }\limits_{i=1}^{n}{l}_{i}$$ SURFACE (S) The spine Surface area is

the sum of all the triangle surfaces (s): $$S=\mathop{\sum }\limits_{i=1}^{f}{s}_{i}$$ A triangle surface (s) is defined for every face (f) of the spine. For each triangle (_i_) with

summits A, B, and C: $${s}_{i}=\frac{1}{2}\left|\overrightarrow{{AB}} \times \overrightarrow{{AC}} \right|$$ VOLUME (V) The spine Volume is the sum of the entire tetrahedron volume (v):

$$V=\mathop{\sum }\limits_{i=1}^{f}{v}_{i}$$ Each tetrahedron is defined by 4 vertices corresponding to triangles A, B, and C, and the spine center (SC) for all three-space coordinates (x,

y, z). The tetrahedron volume is then calculated: $${v}_{i}=\frac{1}{6}\left(\overrightarrow{{AB}} \times \overrightarrow{{AC}} \right)\cdot A{S}_{c}$$ HULL VOLUME (HV) The Hull Volume

represents the smallest convex set containing all the vertices of a geometric shape. The calculation of the Hull Volume is performed using the built-in function of the Python package trimesh

3.7.10, which is based on the Quickhull algorithm57. HULL RATIO (HR) The Hull Ratio is determined as: $${HR}=\frac{{HV}-V}{V}$$ It can represent the complexity of the structure. The higher

the score, the more complex the mesh. AVERAGE DISTANCE (AD) The Average Distance represents the mean distance between each vertex (N) and the spine base center.

$${AD}=\frac{1}{N}\mathop{\sum }\limits_{i=1}^{N}\left(\vec{\left|\vec{{l}_{i}}\right|}\right)$$ COEFFICIENT OF VARIATION IN DISTANCE (CVD) The Coefficient of Variation in Distance

represents the standard deviation of the variation of distance between the base of the spines and each vertex. $${CVD}=\frac{\sqrt{\frac{\mathop{\sum

}\nolimits_{i=1}^{N}{\left|{l}_{i}-{{{{{\rm{\mu }}}}}}\right|}^{2}}{N}}}{{AD}}$$ A high CVD is correlated with a large variation between the distance of the spine base center and the

vertices. A high CVD often leads to mushroom-like spines while a small CVD leads to small stubby or small thin spines. OPEN ANGLE (OA) The Open Angle corresponds to the average angle between

the spine axis and each vertex vector. The spine axis was defined as the vector crossing the gravity center (Gc) and the mesh base center (Sbc). The vertex vector is defined as the vector

(li) crossing the vertex and the mesh base center. $${OA}=\frac{1}{N}\mathop{\sum }\limits_{i=1}^{N}{\cos }^{-1}\left(\overrightarrow{{G}_{c}{S}_{bc}} \cdot

\overrightarrow{{l}_{i}{S}_{bc}}\right)$$ Large head spines are associated with a higher OA value, and thin spines with a low OA value. MEAN CURVATURE (MC) The Mean Curvature corresponds to

the mean of the curvature of each face of the mesh. It was calculated using trimesh58 and was then normalized to the surface. $${MC}=\mathop{\sum }\limits_{i=1}^{N}\frac{m{c}_{i}}{{A}_{i}}$$

MEAN GAUSSIAN CURVATURE (GC) The Mean Gaussian Curvature corresponds to the mean of the gaussian curvature of each face of the mesh. The main difference between GC and MC is that GC is

quadratic while MC is linear. It was calculated using trimesh based on58 and was then normalized to the surface. DIMENSION REDUCTION, CLUSTERING, AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS The correlation

matrix was calculated, and a PCA was performed using the Python package scikit-learn 1.0.2. A clustering analysis without implementing PCA on the five features was performed. For this

analysis, we computed the same three different scores: Silhouette, Elbow, and Calinski-Harabasz to determine the optimal number of clusters. Notably, these scores yielded differing

recommendations regarding the number of clusters. We hypothesize that the observed variance in cluster strength may be due to the lack of dimension reduction in this particular analysis.

Without the application of PCA, metrics of lower significance potentially gain more influence, and as a result, the impact of noise within the dataset is likely to be more pronounced. This

exploratory test highlights the value of dimension reduction techniques like PCA in enhancing the robustness of clustering analyses. We used PCA to reduce the number of features from five to

three independent components. Altogether, these three Principal Components (PC) contained 85.4% of the variance in the dataset. The clustering was performed using the K-Means algorithm59

included in scikit-learn 1.0.2. The number of clusters was determined and was validated using three different scores: the Calinski-Harabz score60, the Silhouette score61, and the Elbow

score62. After clustering, the significance between the percentage of each cluster was determined using a two-independent proportion Agresti-Caffo test, which is available in statsmodels63.

_P_ < 0.05 are considered statistically significant (*_p_ < 0.05, **_p_ < 0.01, ***_p_ < 0.001). The Python package seaborn 0.12.1dev0 was used to generate the KDE maps. The

Python package pingouin 0.5.3 was used to calculate Cohen’s term _d_. An effect lower than 0.01 is considered very small while an effect lower than 0.20 is considered small. To evaluate the

potential lack of independence and variability between groups in the data, particularly considering that many spines share the same cell and animal, the Intracluster Correlation Coefficient

(ICC) was employed. This was calculated using pingouin version 0.5.3. For the spine density of the simple go/no experiment, the ICC is 0.8399. For the spine density of the complex go/no

experiment, the ICC is 0.8275. Finally, for the spine density of the sensory deprivation experiment, the ICC is 0.8967. Since these coefficients are above 0.75, these results demonstrate

that inter-cell/mouse variability is not significant in the dataset64. REPORTING SUMMARY Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked

to this article. DATA AVAILABILITY The source data for the graphs in the paper can be found in Supplementary Data 1. Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be

directed to and will be fulfilled by the co-corresponding authors, Dr. Armen Saghatelyan ([email protected]) and Dr. Simon V. Hardy ([email protected]). CODE AVAILABILITY Codes for

the reconstruction and the analysis65 are available at https://zenodo.org/records/10622371. REFERENCES * Erzurumlu, R. S. & Gaspar, P. Development and critical period plasticity of the

barrel cortex. _Eur. J. Neurosci._ 35, 1540–1553 (2012). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Malvaut, S. & Saghatelyan, A. The role of adult-born neurons in the constantly

changing olfactory bulb network. _Neural Plast._ 2016, 1614329 (2016). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Denoth-Lippuner, A. & Jessberger, S. Formation and integration of new neurons

in the adult hippocampus. _Nat. Rev. Neurosci._ 22, 223–236 (2021). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Hardy, D. & Saghatelyan, A. Different forms of structural plasticity in the

adult olfactory bulb. _Neurogenesis_ 4, e1301850 (2017). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Sailor, K. A. et al. Persistent structural plasticity optimizes sensory

information processing in the olfactory bulb. _Neuron_ 91, 384–396 (2016). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Wu, Z. et al. Context-dependent decision making in a

premotor circuit. _Neuron_ 106, 316–328. e6 (2020). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Lepousez, G. et al. Olfactory learning promotes input-specific synaptic plasticity in adult-born

neurons. _Proc. Natl Acad. Sci._ 111, 13984–13989 (2014). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Lledo, P.-M. & Saghatelyan, A. Integrating new neurons into the adult

olfactory bulb: joining the network, life–death decisions, and the effects of sensory experience. _Trends Neurosci._ 28, 248–254 (2005). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar *

Bastien‐Dionne, P. O. et al. Role of sensory activity on chemospecific populations of interneurons in the adult olfactory bulb. _J. Comp. Neurol._ 518, 1847–1861 (2010). Article PubMed

Google Scholar * Kelsch, W. et al. A critical period for activity-dependent synaptic development during olfactory bulb adult neurogenesis. _J. Neurosci._ 29, 11852–11858 (2009). Article

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Breton-Provencher, V. et al. Principal cell activity induces spine relocation of adult-born interneurons in the olfactory bulb. _Nat. Commun._

7, 12659 (2016). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Malvaut, S. et al. CaMKIIα expression defines two functionally distinct populations of granule cells involved in

different types of odor behavior. _Curr. Biol._ 27, 3315–3329. e6 (2017). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Belnoue, L. et al. A critical time window for the recruitment of bulbar

newborn neurons by olfactory discrimination learning. _J. Neurosci._ 31, 1010–1016 (2011). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Magavi, S. S. et al. Adult-born and

preexisting olfactory granule neurons undergo distinct experience-dependent modifications of their olfactory responses in vivo. _J. Neurosci._ 25, 10729–10739 (2005). Article CAS PubMed

PubMed Central Google Scholar * Malvaut, S. & Saghatelyan, A. Regeneration in the olfactory bulb. In _the senses: A Comprehensive Reference_ (ed. Fritzsch, B.) 610–623 (Academic Press,

2020). * Alonso, M. et al. Activation of adult-born neurons facilitates learning and memory. _Nat. Neurosci._ 15, 897–904 (2012). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Li, W. L. et al.

Adult-born neurons facilitate olfactory bulb pattern separation during task engagement. _Elife_ 7, e33006 (2018). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Grelat, A. et al.

Adult-born neurons boost odor-reward association. _Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA_ 115, 2514–2519 (2018). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Kharazia, V. N. & Weinberg,

R. J. Immunogold localization of AMPA and NMDA receptors in somatic sensory cortex of albino rat. _J. Comp. Neurol._ 412, 292–302 (1999). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Takumi, Y.

et al. Different modes of expression of AMPA and NMDA receptors in hippocampal synapses. _Nat. Neurosci._ 2, 618–624 (1999). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Ganeshina, O. et al.

Differences in the expression of AMPA and NMDA receptors between axospinous perforated and nonperforated synapses are related to the configuration and size of postsynaptic densities. _J.

Comp. Neurol._ 468, 86–95 (2004). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Arellano, J. I., et al., Ultrastructure of dendritic spines: correlation between synaptic and spine morphologies.

_Front. Neurosci_. 1,131–143 (2007). * Tønnesen, J. et al. Spine neck plasticity regulates compartmentalization of synapses. _Nat. Neurosci._ 17, 678–685 (2014). Article PubMed Google

Scholar * Rodriguez, A. et al. Automated three-dimensional detection and shape classification of dendritic spines from fluorescence microscopy images. _PloS One_ 3, e1997 (2008). Article

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Ghani, M. U. et al. Dendritic spine classification using shape and appearance features based on two-photon microscopy. _J. Neurosci. Methods_ 279,

13–21 (2017). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Bokota, G. et al. Computational approach to dendritic spine taxonomy and shape transition analysis. _Front. Comput. Neurosci._ 10, 140

(2016). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Pchitskaya, E. & Bezprozvanny, I. Dendritic spines shape analysis—classification or clusterization? Perspective. _Front.

Synaptic Neurosci._ 12, 31 (2020). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Ghani, M. U., et al. Dendritic spine shape analysis: a clustering perspective. In _Proc._ _Computer

Vision–ECCV 2016 Workshops: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, October 8–10 and 15–16, 2016, Proceedings, Part I 14_ (Springer, 2016). * Ekaterina, P. et al. SpineTool is an open-source software

for analysis of morphology of dendritic spines. _Sci. Rep._ 13, 10561 (2023). Article CAS Google Scholar * Zuo, Y. et al. Long-term sensory deprivation prevents dendritic spine loss in

primary somatosensory cortex. _Nature_ 436, 261–265 (2005). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Brooks, T. F. & Humphreys, W. M. A deconvolution approach for the mapping of acoustic

sources (DAMAS) determined from phased microphone arrays. _J. Sound Vib._ 294, 856–879 (2006). Article Google Scholar * Dougherty, R. Extensions of DAMAS and benefits and limitations of

deconvolution in beamforming. In _Proc._ _11th AIAA/CEAS Aeroacoustics Conference_ (AIAA, 2005). * Viola, P. and W. M. Wells. Alignment by maximization of mutual information. In _Proc. IEEE

International Conference on Computer Vision_ (IEEE, 1995). * Alvarez, L., et al. Morphological snakes. In _Proc_. _2010_ _IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern

Recognition_ (IEEE, 2010). * Chan, T. F. & Vese, L. A. Active contours without edges. _IEEE Trans. Image Process._ 10, 266–277 (2001). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar *

Marquez-Neila, P., Baumela, L. & Alvarez, L. A morphological approach to curvature-based evolution of curves and surfaces. _IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell._ 36, 2–17 (2013).

Article Google Scholar * Lewiner, T. et al. Efficient implementation of marching cubes’ cases with topological guarantees. _J. Graph. Tools_ 8, 1–15 (2003). Article Google Scholar *

Lorensen, W. E. & Cline, H. E. Marching cubes: a high resolution 3D surface construction algorithm. _ACM SIGGRAPH Comput. Graph._ 21, 163–169 (1987). Article Google Scholar * Schober,

P., Boer, C. & Schwarte, L. A. Correlation coefficients: appropriate use and interpretation. _Anesth. Analg._ 126, 1763–1768 (2018). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Yuste, R. &

Bonhoeffer, T. Genesis of dendritic spines: insights from ultrastructural and imaging studies. _Nat. Rev. Neurosci._ 5, 24–34 (2004). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Lagier, S.,

Carleton, A. & Lledo, P.-M. Interplay between local GABAergic interneurons and relay neurons generates γ oscillations in the rat olfactory bulb. _J. Neurosci._ 24, 4382–4392 (2004).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Fukunaga, I. et al. Independent control of gamma and theta activity by distinct interneuron networks in the olfactory bulb. _Nat.

Neurosci._ 17, 1208–1216 (2014). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Sailor, K. A., Schinder, A. F. & Lledo, P.-M. Adult neurogenesis beyond the niche: its potential

for driving brain plasticity. _Curr. Opin. Neurobiol._ 42, 111–117 (2017). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Lledo, P.-M., Alonso, M. & Grubb, M. S. Adult neurogenesis and

functional plasticity in neuronal circuits. _Nat. Rev. Neurosci._ 7, 179 (2006). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Forest, J. et al. Short-term availability of adult-born neurons for

memory encoding. _Nat. Commun._ 10, 5609 (2019). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Saghatelyan, A. et al. Activity-dependent adjustments of the inhibitory network in

the olfactory bulb following early postnatal deprivation. _Neuron_ 46, 103–116 (2005). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Mandairon, N. et al. Involvement of newborn neurons in

olfactory associative learning? The operant or non-operant component of the task makes all the difference. _J. Neurosci._ 31, 12455–12460 (2011). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google

Scholar * Tronel, S. & Sara, S. J. Mapping of olfactory memory circuits: region-specific c-fos activation after odor-reward associative learning or after its retrieval. _Learn. Mem._

9, 105–111 (2002). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Luengo-Sanchez, S. et al. 3D morphology-based clustering and simulation of human pyramidal cell dendritic spines. _PLoS

Comput. Biol._ 14, e1006221 (2018). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Batista-Brito, R. et al. The distinct temporal origins of olfactory bulb interneuron subtypes. _J.

Neurosci._ 28, 3966–3975 (2008). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Hardy, D. et al. The role of calretinin-expressing granule cells in olfactory bulb functions and odor

behavior. _Sci. Rep._ 8, 9385 (2018). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Kucharski, D. & Hall, W. New routes to early memories. _Science_ 238, 786–788 (1987). Article

CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Cummings, D., Henning, H. & Brunjes, P. Olfactory bulb recovery after early sensory deprivation. _J. Neurosci._ 17, 7433–7440 (1997). Article CAS PubMed

PubMed Central Google Scholar * Schneider, C. A., Rasband, W. S. & Eliceiri, K. W. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. _Nat. methods_ 9, 671–675 (2012). Article CAS

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Kashiwagi, Y. et al. Computational geometry analysis of dendritic spines by structured illumination microscopy. _Nat. Commun._ 10, 1285 (2019).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Cignoni, P. et al. Meshlab: an open-source mesh processing tool. In _Proc. Eurographics Italian Chapter Conference_ 129–136 (Eurographics

Association, 2008). * Barber, C. B., Dobkin, D. P. & Huhdanpaa, H. The quickhull algorithm for convex hulls. _ACM Trans. Math. Softw. (TOMS)_ 22, 469–483 (1996). Article Google Scholar

* Cohen-Steiner, D. & Morvan, J.-M. Restricted delaunay triangulations and normal cycle. In _Proc. Nineteenth Annual Symposium on Computational Geometry_ 312–321 (Association for

Computing Machinery, 2003). * Arthur, D. & Vassilvitskii, S. _k-means++: The advantages of careful seeding_ (Stanford, 2006). * Caliński, T. & Harabasz, J. A dendrite method for

cluster analysis. _Commun. Stat.-Theory Methods_ 3, 1–27 (1974). Article Google Scholar * Rousseeuw, P. J. Silhouettes: a graphical aid to the interpretation and validation of cluster

analysis. _J. Comput. Appl. Math._ 20, 53–65 (1987). Article Google Scholar * Yuan, C. & Yang, H. Research on K-value selection method of K-means clustering algorithm. _J_ 2, 226–235

(2019). Google Scholar * Agresti, A. & Caffo, B. Simple and effective confidence intervals for proportions and differences of proportions result from adding two successes and two

failures. _Am. Statistician_ 54, 280–288 (2012). Article Google Scholar * Aarts, E. et al. A solution to dependency: using multilevel analysis to accommodate nested data. _Nat. Neurosci._

17, 491–496 (2014). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Ferreira, A., et al. Spine reconstruction and analysis pipeline for Distinct forms of structural plasticity of adult-born mouse

interneuron spines induced by different odor learning paradigms. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10622371(2024) Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This work was supported by a

Canadian Institute of Health Research (CIHR) grant to A.S., National Science and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) grants to S.V.H. and A.S., and a Le Fonds de recherche du

Québec—Nature et technologies (FRQNT) team grant to A.S. and S.V.H. AUTHOR INFORMATION AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * CERVO Brain Research Center, Quebec City, QC, G1J 2G3, Canada Aymeric

Ferreira, Vlad-Stefan Constantinescu, Sarah Malvaut, Armen Saghatelyan & Simon V. Hardy * Department of Biochemistry, Microbiology, and Bioinformatics, Université Laval, Quebec City, QC,

G1V 0A6, Canada Aymeric Ferreira & Simon V. Hardy * Department of Psychiatry and Neuroscience, Université Laval, Quebec City, QC, G1V 0A6, Canada Vlad-Stefan Constantinescu, Sarah

Malvaut & Armen Saghatelyan * Department of Cellular and Molecular Medicine, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, ON, K1N 6N5, Canada Armen Saghatelyan * Department of Computer Science and

Software Engineering, Université Laval, Quebec City, QC, G1V 0A6, Canada Simon V. Hardy Authors * Aymeric Ferreira View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed

Google Scholar * Vlad-Stefan Constantinescu View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Sarah Malvaut View author publications You can also search

for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Armen Saghatelyan View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Simon V. Hardy View author publications You

can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CONTRIBUTIONS A.F. performed the computational analyses of the spines of adult-born neurons. V.S.C. and S.M. performed the

experiments and acquired the images. S.V.H. and A.S. supervised the computational and experimental work, respectively. All the authors discussed the data, and A.F., S.M., A.S., and S.V.H.

wrote the manuscript. CORRESPONDING AUTHORS Correspondence to Armen Saghatelyan or Simon V. Hardy. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS The authors declare no competing interests. PEER

REVIEW PEER REVIEW INFORMATION _Communications Biology_ thanks Matthew Grubb, Ali Ozgur Argunsah, and Andreas (M) Kist for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary

Handling Editors: George Inglis and Benjamin Bessieres. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION PUBLISHER’S NOTE Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and

institutional affiliations. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION DESCRIPTION OF ADDITIONAL SUPPLEMENTARY FILES SUPPLEMENTARY DATA 1 REPORTING SUMMARY RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS

OPEN ACCESS This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or

format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or

other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in

the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the

copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Ferreira, A.,

Constantinescu, VS., Malvaut, S. _et al._ Distinct forms of structural plasticity of adult-born interneuron spines in the mouse olfactory bulb induced by different odor learning paradigms.

_Commun Biol_ 7, 420 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-024-06115-7 Download citation * Received: 27 July 2023 * Accepted: 27 March 2024 * Published: 06 April 2024 * DOI:

https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-024-06115-7 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not

currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative