Play all audios:

ABSTRACT Coronary heart disease (CHD) is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality for people worldwide, yet differences in the likelihood of receiving optimal care occur depend on

gender. This study therefore aimed to explore the healthcare experiences of men and women living with CHD. A systematic search of qualitative research was undertaken, following PRISMA

guidelines. Forty-three studies were included for review, involving 1512 people (62% women, 38% men; 0% non-binary or gender diverse). Thematic synthesis of the data identified four themes:

(1) assumptions about CHD; (2) gender assigned roles; (3) interactions with health care; and (4) return to ‘normal’ life. A multilevel approach across the entire ecosystem of healthcare is

required to improve equity in care experienced by people living with CHD. This will involve challenging both the individuals’ knowledge of CHD and awareness of health professionals to

entrenched gender bias in the health system that predominantly favours men. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS PREVENTING ISCHEMIC HEART DISEASE IN WOMEN: A SYSTEMATIC REVIEW OF GLOBAL

DIRECTIVES AND POLICIES Article Open access 31 October 2024 TREATMENT BURDEN AMONG PATIENTS WITH HEART FAILURE ATTENDING CARDIAC CLINIC OF TIKUR ANBESSA SPECIALIZED HOSPITAL: AN EXPLANATORY

SEQUENTIAL MIXED METHODS STUDY Article Open access 07 November 2022 EVALUATION OF THE PSYCHOMETRIC PROPERTIES OF THE CARDIAC DISTRESS INVENTORY IN IRANIAN PATIENTS WITH HEART DISEASE Article

Open access 16 May 2025 INTRODUCTION Coronary heart disease (CHD) has historically been perceived as a disease affecting middle-aged men; however, it is the leading cause of mortality and

morbidity for people globally1. Literature highlights women with CHD experiencing poorer short- and long-term outcomes relative to similarly affected men, with further disparities in care

and outcomes observed for subgroups of women especially among racial and ethnic minorities, women with lower education levels and those socially disadvantaged2,3,4,5. Despite decades of

awareness campaigns and education, quantitative studies from around the world have demonstrated gender differences at all stages of the healthcare journey, from primary care through to

secondary prevention. In a study of just over 53,000 individuals (58% women, 42% men, 0% non-binary/gender diverse people), women were less likely to have a cardiovascular risk assessment

conducted in primary health care services (odds ratio (OR) 0.88 [0.81 to 0.96])6. This disparity in the management of vascular disease was also reported in a study of more than 130,000

patients (47% women, 53% men); which reported women were less likely to be prescribed recommended medications and assessed for cardiovascular risk by their general practitioners7. Gender

differences are also reported in relation to hospital presentation, with two large-scale studies in America and Sweden observing a link between women’s prehospital delays and greater

mortality rates following ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarctions8,9. Further gender differences can be seen with treatment upon arrival at a tertiary hospital. For example, an

Australian study that investigated 54,138 people (48.7% women) who presented to three emergency departments experiencing non-traumatic chest pain reported that women received suboptimal care

relative to men as they transitioned through the health service: compared with men, women were significantly less likely to be seen within 10 min of arriving at the emergency department,

less likely to have a troponin test undertaken, less likely to be admitted to specialised care, and more likely to die during their hospital admission (OR 1.36 [1.12, 1.66])10. Moreover,

regardless of age, more women will die within a year of a first acute myocardial infarction (AMI) (26% of women compared to 19% of men) and will have complications of heart failure and

stroke within 5 years of their first AMI (47% of women vs. 36% of men)11. These findings imply the existence of a structural gender bias in healthcare settings towards the diagnosis and

subsequent treatment of CHD, which has been supported in the literature. For example, a study of over 500 cardiologists in the US reported an implicit gender bias in simulated clinical

decision-making for suspected CHD, with the majority associating strength or risk taking implicitly with male more than female patients12. Another recent research concluded that among

patients resuscitated after experiencing out-of-hospital cardiac arrest, discharge survival was significantly lower in women than in men, especially among patients considered to have a

favourable prognosis11. The existence of gender bias persists in secondary prevention. For example, in a study of 9283 individuals with acute coronary syndrome patients (29% women, 71% men),

women had lower odds of attending cardiac rehabilitation compared to men (OR 0.87 [0.78, 0.98])13. Further, a review of the literature found women to have lower referral, enrolment and

completion for important secondary prevention programs such as cardiac rehabilitation14. However, it is important to note that these observations have focused on sex (biological,

physiological, hormonal, genetic) differences rather than gender (described often as socially constructed through shared structures and experiences). It is also important to note that these

studies have relied on a binary conception of sex and gender that is now considered both inappropriate and inaccurate with growing evidence on the spectrum-like nature of these concepts15.

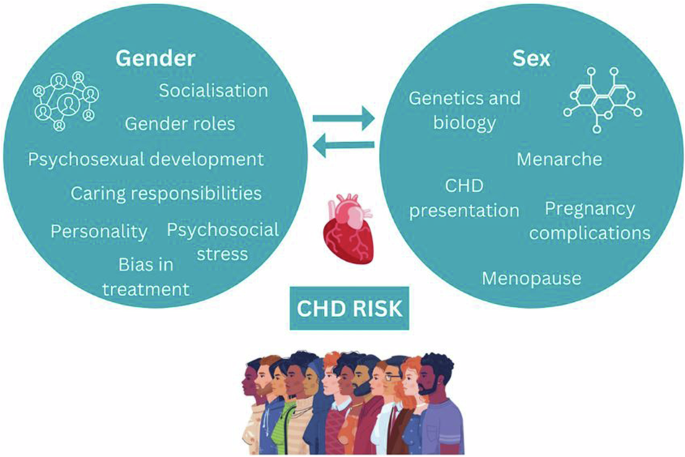

The terms sex and gender are often conflated in the scientific literature16. While sex is considered to be an important biological determinant of health accounting for physiological

differences, gender, also requires consideration for its influence on health outcomes (refer Fig. 1). Gender identities, socialisation, roles, and access to resources are factors that have

been shown to contribute to health outcomes17 with increasing evidence of the influence of psychosocial development as a result of genetics, hormonal and psychosocial influences for

additional consideration18. A previous systematic review explored patients’ experiences of CHD using a gender-sensitive approach19. The review included 60 qualitative studies (published

before 2004), and the identified studies were conducted almost exclusively with men until the late 1990s when the focus changed to women. However, they noted that most studies did not have a

gender focus and called for more work taking gender roles into account when exploring experiences of people with CHD. In supporting improved outcomes in people’s heart health, more research

is needed to examine the reasons for evidenced, gender-based disparities. Exploring the lived experiences of CHD from the perspective of multiple genders beyond the gender binary will

promote a deeper understanding of the healthcare journey and inform interventions for CHD management20. Therefore, the aim of this study was to synthesise qualitative research on experiences

and perceptions of CHD and associated healthcare from the perspective of people of any gender identity with CHD and their healthcare professionals. RESULTS In total, 266 studies were

screened, of which 43 studies were included (Fig. 2). Eleven studies were conducted in the United States of America21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31, nine were from the United

Kingdom32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40, seven were from Canada41,42,43,44,45,46,47, five were from Sweden48,49,50,51,52, three were from Australia53,54,55, two were from Finland56,57, and one

study each from Austria, Brazil, Denmark, Italy, New Zealand, and Spain (Supplementary Table 1)58,59,60,61,62,63. Of the included studies, a total of 1522 people (62% women; people with CHD

or CHD health professionals) were included. Twenty studies focused on the experiences of women with CHD22,24,28,29,34,36,37,38,39,40,41,47,48,49,50,53,55,63, three studies focused on the

experiences of men with CHD46,60,62, 19 studies included a combination of women and men21,23,25,26,27,32,33,35,42,43,44,52,54,56,57,59,61, and two studies did not report gender

breakdown31,51. There were no studies that reported non-binary, gender diverse, or transgender people. Three studies included healthcare professionals only31,51,58, one study included people

with CHD and healthcare professionals30, and one study included people with CHD and carers45. A variety of qualitative data collection methods were utilised, including interviews, interview

following presentation of vignettes, content analysis, and focus groups. Few studies provided summary statistics on socioeconomic status (_n_ = 6) and education (_n_ = 14), respectively.

The heterogeneity and limited data inhibited our ability to combine the data for meta-analysis. QUALITY ASSESSMENT Among the included studies, 8 (18.6%) were rated as high quality, 29

(67.4%) as medium quality and 6 (13.9%) as low quality (Supplementary Table 1). The six low quality studies differed from the high-quality studies as they lacked a coherent explanation of

theoretical underpinnings of their study design and did not adequately consider the relationship between participants and researchers. Low quality studies were sporadically spread across

this study’s thematic outcomes, therefore minimising risk of bias. STUDY THEMES Four major themes were identified: assumptions about CHD (interpretation of signs and symptoms, help seeking);

gender assigned roles; interactions with health care; and return to ‘normal’ life. ASSUMPTIONS ABOUT CHD: INTERPRETATION OF SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS Studies reported that women and men held

assumptions regarding CHD, particularly around their perception of who was a ‘typical’ heart attack candidate. The assumption of CHD as a ‘man’s disease’ was cited frequently and led many

women to question their own signs and symptoms. Women reported a high level of uncertainty about their symptoms (_n_ = 12 studies), often attributing any signs or symptoms to non-cardiac

causes such as old age, arthritis, or fatigue and often trying to persuade themselves that the symptoms would disappear with rest22,23,24,28,30,35,36,37,41,48,49,60. This was often linked to

symptoms not aligning with what women thought as a ‘typical heart attack’, as there was no acute crushing chest pain as often described, instead, often reporting a gradual onset of symptoms

such as feelings of nausea and breathlessness, causing a level of confusion and delays in seeking help28,31,32,53,58. In contrast, men were more explicit in their symptom descriptions and

more commonly recognised them as cardiac symptoms, that warranted medical attention23,60,63 Riegel et al.23 suggested this was due to men being more confident in their decision-making,

having greater social support and symptoms being more aligned with the public perception of CHD as a man’s disease. Similarly, identifying CHD signs and symptoms were also more difficult due

to assumptions of the typical ‘heart attack’ patient – often described in studies as male, overweight, smokers, who did little exercise. Participants were therefore confused as to what was

happening if their own self-image differed, especially women who thought they were not at risk unless they had adopted ‘a man’s way of life’23,38,39. ASSUMPTIONS ABOUT CHD: HELP SEEKING

Women often delayed seeking medical help, preferring to ‘wait and see’. Studies reported the delays were often due to confusion over signs and symptoms not aligning with prior perceptions of

CHD, with women self-medicating or resting to see if the signs would pass before ‘bothering’ others23,27,30,33,37,58. Studies described women not wanting to be seen by others as a

‘nuisance’, ‘ignorant’ or a ‘hypochondriac’ and as such, they were more likely to wait until they were incapacitated to seek medical help. Women also spoke of important activities and

responsibilities that prevented or forestalled seeking medical attention22,49,52. Concern for the family often led to ignoring symptoms, because responsibilities, such as housework or caring

for other family members, could not be delegated to others, and treating symptoms failed to ‘fit’ into their lives22. Seeking advice from friends or family before seeking medical attention

was commonly reported by both women and men, with many only seeking healthcare due to the friend or family member’s insistence. Immediate family members, usually daughters, were instrumental

in organising medical attention37. Wives were commonly the impetus for men to seek help, insisting on them acting on symptoms and seeking care37,40,52 and this was reported by Brink et

al.52 as being one of the reasons why men sought medical attention faster than women. However, it was not reported that husbands were the impetus for women to seek help. Women delaying

seeking professional medical care was also often due to logistical concerns such as inadequate transportation, workforce shortages at medical centres, and waiting times, especially in

regional or rural areas22,29,54. Rosenfeld et al.29 reported that women preferred to visit a general practitioner rather than engaging with emergency services as they often felt that their

symptoms were not severe enough to waste emergency services time. GENDER-ASSIGNED ROLES As previously described, women commonly spoke of their sense of responsibility for family and home and

prioritising their duty to others over their own health needs. The interruption to normality in everyday routines for the women reportedly caused anxiety and many attempted to hide their

feelings to shield family members from concern22,49. Studies reported that women were keen to be discharged from hospital following treatment, although many women reported fears of the

future and fear of implication of the illness on their roles as family carers40,47,55. This sense of responsibility for family and home was less often noted by men. Studies observed that men

were often more concerned about their social position and concerned with how their recovery period might impact the way they were seen by others or how they would reconcile with their role

as the ‘breadwinner’ of the family if they were forced to decrease their workload44,45. Cewers et al.51 reported that health professionals tended to have specific gendered role perceptions,

influencing advice regarding recovery at home. Men were seen as the ‘workers’ and were more likely to do sport than women, whereas women were seen as the carers and housekeepers and were

more likely to participate in yoga and walking in their recovery. INTERACTIONS WITH HEALTHCARE Four studies specifically focused on patient experiences with health care professionals, with

gender differences apparent in these interactions22,30,56. Women described not being ‘listened to’ by health professionals and often reported being dismissed due to the lack of specificity

of their symptom descriptions22,40,55. Women also voiced frustration with the lack of information provided regarding their initial diagnoses and discharge40,55. This finding was related to

their need to organise their domestic duties and for their ‘forward planning’. In contrast, health professionals identified that they often saw women as emotional and ‘in distress’, unable

to articulate their symptoms clearly, which made it difficult to reconstruct pain development51,58. These studies concluded that women were more difficult to diagnose as they were often

presenting older, had more complex conditions and were in later stages of illness due to delayed help seeking. Women tended to have stronger emotional responses to their diagnosis than men,

with most women reporting sadness and resignation26,40,59. Checa et al.59 described women’s concern about the future and how their disease could affect their roles within the family, whereas

men tended to be more relaxed and even optimistic about being ‘cured’. However, this contrasted with Evangelista et al.26 who reported women used more optimistic coping strategies than men,

who tended to use more emotion-focused and fatalistic coping strategies. One study, focused on men’s psychological reactions and experiences following a cardiac event, reported participants

had difficulties in adapting to their new postcardiac identity and accepting their new ‘roles’46. RETURN TO NEW NORMAL A desire to return to a familiar lifestyle was reported by both women

and men40,44,47,55. However, women were more often concerned about the practical support they would need on returning home (e.g., shopping, cleaning) than men, and it was reported that women

became avid planners in their recovery to ensure returning to their ‘normal’ lives as soon as possible47. Men reported being fearful of being discharged home as they were unsure of what

life would look like in terms of employability, sexual virility, and other’s perceptions of them44,45. On returning home, women often spoke of loss of control of their home situation and

appeared to equate this loss of role functioning with a diminution in their value as a person34,45,47. Women reported being happy to talk and discuss their illness and hear from other

patients, whereas men were less likely to want to share any thoughts and feelings and often self-isolated44,52. DISCUSSION This review suggests that whilst the experiences of people with

lived experience of CHD are very individualised, there are gendered experiences and perceptions of CHD and associated healthcare. A greater proportion of women participants were included in

this review, which contrasts to all men-only studies prior to 199019. The themes identified in this review will be discussed according to the Ecological model of health behaviour, as it

highlights how gendered experiences span across the multiple levels of influence64. The findings of intrapersonal factors suggest that the perception of CHD as a ‘male disease’ persists

among individuals and healthcare professionals, which influences the CHD ‘journey’ from symptom recognition to rehabilitation for both patients and health professionals. Women were reported

to be more likely than men to seek help in primary care settings, similar to other conditions such as whiplash trauma and mental health52. However, when seeking emergency care, women were

reluctant to burden the hospital system as they lacked knowledge on the urgency of their CHD symptoms, and sometimes did not perceive themselves at risk. Furthermore, similar to previous

findings, women continue to prioritise their family carer role over their own health22. It is possible that these compounding factors will continue to delay women in presenting with CHD

symptoms to emergency and with later presentations, additional co-morbidities can exist, making it more challenging for health professionals to treat effectively. Hence, potentially placing

greater pressures on the health system. Efforts need to be made through health education to dispel gendered perceptions, such as myths of CHD being a ‘male disease’ and building awareness on

socialised gender norms of women’s health seeking behaviour to ensure women recognise early signs and symptoms, that can differ to men’s symptoms and seek help in a timely manner. The CHD

journey has been expressed as stressful from all counterparts, and men with CHD have more commonly expressed to feel isolated throughout their journey. As part of patient management,

additional efforts by health professionals should incorporate emotional and mental health interventions and offer social support to CHD patients65. Women also reported feeling dismissed by

health professionals during their care, however whether their experiences were influenced by gender could be debated as fewer men’s perspectives were available for comparison. These

interpersonal factors however continue to highlight the importance of patient communication and patient centred care. A pathway through which the gender system impacts health is through

gendered health service provision, which can act to disempower gender groups, or leave their health needs unmet66. Traditionally, medical training has been aimed to be predominantly gender

neutral, that is, little or no attention paid to gender differences in medical education. Yet, the interpretation of CHD signs and symptoms are more aligned with men, potentially as CHD

research has disproportionately underrepresented women participants, and women’s presentations have been perceived by health professionals as ‘atypical’. A systematic review and

meta-analysis on the differences in symptom presentation in men and women demonstrated that women are more likely to report experiencing shoulder and neck pain, palpitations and nausea,

whereas men are more likely to experience chest pain. However, it was also noted that there was significant overlap of the symptoms experienced and therefore symptoms should no longer be

labelled as ‘typical’ or ‘atypical’67. Furthermore, some have long argued for the need to address gender bias and develop gender competencies in medical curricula68, and this review

continues to support such recommendations. Challenging conservative practice means holding CHD health professionals, organisations, and systems accountable to their assumptions, knowledges,

and practices that bias male experiences over others. Gender-sensitive approaches to care which are responsive to people’s lived experiences and particular needs, preferences, identities and

circumstances should be emphasised. Women reporting inadequate transportation, healthcare staff shortages and waiting times had impacted them seeking medical care and were outcomes in

women-only studies. These institutional factors require further exploration across the gender spectrum to determine whether a true gendered experience exists on these barriers to accessing

CHD care. With women becoming more educated and increasing their labour force participation, we might expect to see a change in gender norms and therefore potential health behaviours.

However, this review continues to affirm previous findings that gender norms remain relatively stagnant, where post-diagnosis and returning home, women are concerned about their abilities

for undertaking domestic duties, while men are concerned about employability and family financial responsibilities. The traditional gender roles might be due to the older age of

participants, but overall, all patients grappled with their identities and societal roles while living with CHD. Though not all patients fall into the distinct gender social norms, health

professionals should consider individual’s expressed identity that can influence their responses and behaviours towards CHD. Future research into gender disparities should avoid the

traditional binary labelling of sex and gender into ‘male’ and ‘female’ categories and instead, adopt a more realistic and more inclusive approach that considers sex and gender as operating

across a spectrum. This review included studies over a 22-year period, yet only 8 of the 43 studies were published in the last 11 years. While notable changes in CHD care have occurred, the

more recent studies continue to report similar gender differences across all the identified themes. Moreover, the responsiveness of health care professionals and perceptions of patients may

have differed, including those who identify as gender diverse, those with different socioeconomic status and education levels, as well as low- and middle-income countries where the majority

of CHD deaths occur69. This review also excluded studies published in languages other than English, hence limiting perspectives on healthcare experiences and behaviour from non-English

speaking countries with differing cultural and social norms. The findings from this review highlight differences in healthcare experiences of women and men living with coronary heart

disease. However, there are still major gaps in the research. While some quantitative studies from low-middle-income countries have been located70,71, more qualitative research from

low-middle-income countries is needed to provide comparisons with the developing world and better inform tailored intervention strategies. None of the included papers explored the

experiences of gender diverse people. Recommended areas for further investigation include the experiences of transgender, gender diverse people, people from culturally and linguistically

diverse backgrounds, and minority groups (e.g., indigenous people or people with disability). Intersectionality describes the ways in which different parts of a person’s identity can overlap

to increase the experience discrimination and marginalisation72. It is important that future research adopts an intersectional lens, to explore how various factors such as gender, class,

ethnicity, (dis)ability, rurality, sexuality and age impact the experience of CHD. Future research should also explore gendered CHD experiences over time, as factors such as increased public

awareness CHD campaigns, changes in health professional education content and changes in the number of women included in CHD research studies may influence findings. In narrowing the

disparity between men’s access and treatment for CHD compared with women, non-binary, gender diverse, and transgender people, a number of major health initiatives have been introduced aiming

to raise awareness of cardiovascular health. For example, the Australian ‘Her Heart’ initiative aspires to educate and empower women to decrease their risk of developing heart disease and

the American Heart Association’s ‘Go Red for Women’ campaign which similarly aims to empower women to take charge of their heart health64,73. Both campaigns encourage women to participate in

heart disease research, raise awareness of women-specific CHD risk factors and ‘break’ the myths around heart disease being a predominantly male concern. However, many of these health

campaigns target the sex difference in CHD risk, such as understanding the signs of CHD in women. More focus needs to be done to elevate the lives and lived experiences of people whose sex

and/or gender identity is more expansive than the conventional man-women binary. While the awareness of sex and gender influencing CHD research, medicine and public campaigns grows, the

perception of CHD as a ‘male problem’ is longstanding. If not dispelled, this may lead to people continuing to be underdiagnosed and inadequately and inappropriately cared for. Additionally,

and albeit gradually, gender norms will evolve, so we cannot underestimate how individuals’ gender can impact their presentation, reaction and approach to living with CHD. As we also shift

healthcare to personalised care, gender-sensitive approaches are needed to support health professionals and society to embrace a broader disease paradigm, through education, public health

messages, patient advocacy and promote patient-centred multidisciplinary care. METHODS The review was undertaken in line with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and

Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines74 (Supplementary Table 1) and the protocol is provided here. Due to the qualitative nature of this review, the background, experiences and biases of authors

involved in this review should be acknowledged as they potentially influence the content. Therefore, we believe it is important to reflect on our own positionality. The author group

reflects a diverse range of genders and cultural backgrounds and are a cross-disciplinary team of practitioners (rural and metropolitan), all committed to promoting CHD health care. They

worked reflexively together in reviewing and synthesising the data to reduce unconsciously imposing personal beliefs and assumptions. In this way, the author group was committed in remaining

mindful of the benefits and challenges of conducting research from an insider–outsider perspective. It is also acknowledged that the current evidence presented in this review comes

primarily from Western cultures and this geographical and cultural context may shape the findings as they may not universally apply due to cultural differences in gender norms and

expectations. SEARCH STRATEGY The search and inclusion strategy received contributions from authors HB, JL and SG and was reviewed by a University Librarian not otherwise involved in the

review. Specific search terms (along with their synonyms, combinations, Boolean operators, and relevant MeSH/Subject terms) were identified based upon the review question (Supplementary

Table 2). Inclusion and exclusion criteria were developed using the SPIDER tool75 (Supplementary Table 3). The following databases were searched: MEDLINE Complete, CINAHL, PsychINFO,

SocINDEX, Academic Search Complete and EMBASE. The search was limited from 2000 to 2023 and adjusted to suit the requirements of specific databases. STUDY SELECTION The screening process was

facilitated by Covidence (Veritas Health Information, Australia). Acknowledging the challenges with how qualitative research is indexed in electronic databases76, the inclusion and

exclusion criteria were applied in two steps, by two researchers (HB, JL), independently: (1) the _Sample_, _Evaluation_, and _Research Type_ components on screening title and abstracts of

retrieved records, and (2) the _Phenomenon of Interest_ and _Design_ components were applied at the full-text review stage. If any disagreements occurred, discussions were held with a third

reviewer (SG) to reach consensus. QUALITY ASSESSMENT Two researchers (HB, LL) independently assessed the methodological quality and risk of bias of each included article using the Critical

Appraisal Skills Programme’s Qualitative Checklist (CASP-Q)77. Each article was assigned a “high”, “medium”, and “low” quality rating from the CASP-Q scores using Butler, Hall, and Copnell’s

recommendations78. These quality ratings were not used to further exclude articles, but rather to inform on the potential weaknesses of the identified themes. DATA EXTRACTION Summary data

were collected from each article including (HB, CB, LL): author, year, country, sample, mean and range of age, proportion of women, socioeconomic status, education levels, CHD type, study

design, evaluation and research type (Supplementary Table 1). Study findings, along with direct participant quotes, were extracted from each article (HB, CB) using NVivo (Version 20)79. DATA

SYNTHESIS Data synthesis involved an inductive thematic synthesis using the methodology by Thomas and Harden80, supported with NVivo software. Two researchers (HB, JL) familiarised

themselves with each article and then conducted line-by-line coding of text relevant to the synthesis aim. Articles were then loaded into NVivo Version 20 and independently coded by the two

researchers (HB, JL). The researcher specific coding frameworks were then compared, discussed, and merged into one, accounting for bias. The identified themes were then generated in an

iterative process to ensure accuracy and completeness. This stage involved an initial review by a broader team (HB, LL, CB, JL) to achieve consensus, and then presented to the whole

authorship team for comment. PATIENT AND PUBLIC INVOLVEMENT There was no patient or public involvement in this study. DATA AVAILABILITY No datasets were generated or analysed during the

current study. REFERENCES * Roeters van Lennep, J. E., Westerveld, H. T., Erkelens, D. W. & van der Wall, E. E. Risk factors for coronary heart disease: implications of gender.

_Cardiovasc Res._ 53, 538–549 (2002). Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Gupta, N. Research to support evidence-informed decisions on optimizing gender equity in health workforce policy

and planning. _Hum. Resour. Health_ 17, 46 (2019). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Sederholm Lawesson, S., Isaksson, R.-M., Ericsson, M., Ängerud, K. & Thylén, I.

Gender disparities in first medical contact and delay in ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a prospective multicentre Swedish survey study. _BMJ Open_ 8, e020211 (2018). Article PubMed

PubMed Central Google Scholar * Mochari-Greenberger, H., Liao, M. & Mosca, L. Racial and ethnic differences in statin prescription and clinical outcomes among hospitalized patients

with coronary heart disease. _Am. J. Cardiol._ 113, 413–417 (2014). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Balbaa, A., ElGuindy, A., Pericak, D., Natarajan, M. K. & Schwalm, J. D. Before the

door: Comparing factors affecting symptom onset to first medical contact for STEMI patients between a high and low-middle income country. _Int. J. Card. Heart Vasc._ 8, 100978 (2022).

Google Scholar * Hyun, K. K. et al. Gender inequalities in cardiovascular risk factor assessment and management in primary healthcare. _Heart_ 103, 500–506 (2017). Article CAS Google

Scholar * Lee, C. M. Y. et al. ‘Sex disparities in the management of coronary heart disease in general practices in Australia’. _Heart_ 105, 1898–1904 (2019). Article PubMed CAS Google

Scholar * Bugiardini, R. et al. Delayed care and mortality among women and men with myocardial infarction. _J. Am. Heart Assoc._ 6, e005968 (2017). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google

Scholar * Ängerud, K. H., Boman, K. & Brännström, M. Areas for quality improvements in heart failure care: Quality of care from the family members’ perspective. _Scand. J. Caring Sci._

32, 346–353 (2018). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Mnatzaganian, G. et al. Sex disparities in the assessment and outcomes of chest pain presentations in emergency departments. _Heart_

106, 111–118 (2020). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Mody, P. et al. Gender-based differences in outcomes among resuscitated patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. _Circulation_

143, 641–649 (2021). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Daugherty, S. L. et al. Implicit gender bias and the use of cardiovascular tests among cardiologists. _J. Am. Heart Assoc._ 6, 1–11

(2017). Article Google Scholar * Hyun, K. et al. Gender difference in secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease and outcomes following the survival of acute coronary syndrome. _Heart

Lung Circulation_ 30, 121–127 (2021). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Smith, J. R., Thomas, R. J., Bonikowske, A. R., Hammer, S. M. & Olson, T. P. Sex differences in cardiac

rehabilitation outcomes. _Circulation Res._ 130, 552–565 (2022). Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Peters, S. A. & Norton, R. Sex and gender reporting in global health: new

editorial policies. _BMJ Glob. Health_ 3, e001038 (2018). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * O’Neil, A., Scovelle, A. J., Kavanagh, A. & Milner, A. J. Gender/sex as a

social determinant of cardiovascular risk. _Circulation_ 137, 854–864 (2018). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Wood, W. & Eagly, A. H. in _Handbook of Social Psychology_ (eds Fiske, S.

T. Gilbert, D. T. & Lindzey, G.) 5th edn. 629–667 (John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2010). * Fisher, A. D. & Cocchetti, C. in _The Plasticity of Sex_ (ed. Legato, M. J.) 89–107

(Academic Press, 2020). * Emslie, C. Women, men and coronary heart disease: a review of the qualitative literature. _J. Adv. Nurs._ 51, 382–395 (2005). Article PubMed Google Scholar *

Gauci, S. et al. Biology, bias, or both? the contribution of sex and gender to the disparity in cardiovascular outcomes between women and men. _Curr. Atheroscler. Rep._ 24, 701–708 (2022).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Rankin, S. H. et al. Recovery trajectory of unpartnered elders after myocardial infarction: an analysis of daily diaries. _Rehabil. Nurs._

27, 95–102 (2002). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Schoenberg, N. E., Peters, J. C. & Drew, E. M. Unraveling the mysteries of timing: women’s perceptions about time to treatment for

cardiac symptoms. _Soc. Sci. Med._ 56, 271–284 (2003). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Riegel, B. et al. Gender-specific barriers and facilitators to heart failure self-care: a mixed

methods study. _Int J. Nurs. Stud._ 47, 888–895 (2010). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Blakeman, J. R. et al. Women’s prodromal myocardial infarction symptom perception, attribution, and

care seeking: a qualitative multiple case study. _Dimens Crit. Care Nurs._ 41, 330–339 (2022). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Tomczyk, S. & Treat-Jacobson, D. Claudication symptom

experience in men and women: Is there a difference? _J. Vasc. Nurs._ 27, 92–97 (2009). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Evangelista, L. S., Kagawa-Singer, M. & Dracup, K. Gender

differences in health perceptions and meaning in persons living with heart failure. _Heart Lung_ 30, 167–176 (2001). Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Kreatsoulas, C. et al. Patient

risk interpretation of symptoms model (PRISM): how patients assess cardiac risk. _J. Gen. Intern. Med._ 36, 2205–2211 (2021). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * McSweeney, J.

C., Cody, M. & Crane, P. B. Do you know them when you see them? Women’s prodromal and acute symptoms of myocardial infarction. _J. Cardiovasc. Nurs._ 15, 26–38 (2001). Article PubMed

CAS Google Scholar * Rosenfeld, A. G., Lindauer, A. & Darney, B. G. Understanding treatment-seeking delay in women with acute myocardial infarction: descriptions of decision-making

patterns. _Am. J. Crit. Care_ 14, 285–293 (2005). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Miller, C. L. Cue sensitivity in women with cardiac disease. _Prog. Cardiovasc. Nurs._ 15, 82–89 (2000).

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Welch, L. C. et al. Gendered uncertainty and variation in physicians’ decisions for coronary heart disease: the double-edged sword of “atypical

symptoms. _J. Health Soc. Behav._ 53, 313–328 (2012). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Philpott, S. et al. Gender differences in descriptions of angina symptoms and health

problems immediately prior to angiography: the ACRE study. appropriateness of coronary revascularisation study. _Soc. Sci. Med._ 52, 1565–1575 (2001). Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar *

Richards, H. M., Reid, M. E. & Watt, G. C. Why do men and women respond differently to chest pain? A qualitative study. _J. Am. Med. Women’s Assoc._ 57, 79–81 (2002). Google Scholar *

White, J., Hunter, M. & Holttum, S. How do women experience myocardial infarction? A qualitative exploration of illness perceptions, adjustment and coping. _Psychol. Health Med._ 12,

278–288 (2007). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Emslie, C., Hunt, K. & Watt, G. Invisible women? The importance of gender in lay beliefs about heart problems. _Sociol Health Illn._

23, 203–233 (2001). Article Google Scholar * Higginson, R. Women’s help-seeking behaviour at the onset of myocardial infarction. _Br. J. Nurs._ 17, 10–14 (2008). Article PubMed Google

Scholar * Lockyer, L. Women’s interpretation of their coronary heart disease symptoms. _Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs._ 4, 29–35 (2005). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Ruston, A. &

Clayton, J. Coronary heart disease: women’s assessment of risk-a qualitative study. _Health Risk Soc._ 4, 125–137 (2002). Article Google Scholar * Ruston, A. & Clayton, J. Women’s

interpretation of cardiac symptoms at the time of their cardiac event: the effect of co-occurring illness. _Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs._ 6, 321–328 (2007). Article PubMed Google Scholar *

Banner, D. et al. Women’s experiences of undergoing coronary artery bypass graft surgery. _J. Adv. Nurs._ 68, 919–930 (2012). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Turris, S. A. Women’s

decisions to seek treatment for the symptoms of potential cardiac illness. _J. Nurs. Scholarsh._ 41, 5–12 (2009). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Galdas, P. M. et al. Help seeking for

cardiac symptoms: beyond the masculine-feminine binary. _Soc. Sci. Med._ 71, 18–24 (2010). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * King, K. M. et al. Men and women managing

coronary artery disease risk: urban-rural contrasts. _Soc. Sci. Med._ 62, 1091–1102 (2006). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Costello, J. A. & Boblin, S. What is the experience of men

and women with congestive heart failure? _Can. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs._ 14, 9–20 (2004). PubMed Google Scholar * Freydberg, N. et al. “If he gives in, he will be gone…”: the influence of work

and place on experiences, reactions and self-care of heart failure in rural Canada. _Soc. Sci. Med._ 70, 1077–1083 (2010). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Jbilou, J. et al. Understanding

men’s psychological reactions and experience following a cardiac event: a qualitative study from the MindTheHeart project. _BMJ Open_ 9, e029560 (2019). Article PubMed PubMed Central

Google Scholar * Kerr, E. E. & Fothergill-Bourbonnais, F. The recovery mosaic: older women’s lived experiences after a myocardial infarction. _Heart Lung_ 31, 355–367 (2002). Article

PubMed Google Scholar * Gyberg, A. et al. Women’s help-seeking behaviour during a first acute myocardial infarction. _Scand. J. Caring Sci._ 30, 670–677 (2016). Article PubMed Google

Scholar * Sjostrom-Strand, A. & Fridlund, B. Women’s descriptions of symptoms and delay reasons in seeking medical care at the time of a first myocardial infarction: a qualitative

study. _Int J. Nurs. Stud._ 45, 1003–1010 (2008). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Wieslander, I. et al. Women’s experiences of how their recovery process is promoted after a first

myocardial infarction: Implications for cardiac rehabilitation care. _Int J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-being_ 11, 30633 (2016). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Cewers, E. et al. Physical

activity recommendations for patients with heart failure based on sex: a qualitative interview study. _J. Rehabil. Med_ 51, 532–538 (2019). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Brink, E.,

Grankvist, G., Karlson, B. W. & Hallberg, L. R. M. Health-related quality of life in women and men one year after acute myocardial infarction. Quality of Life Research: An International

Journal of Quality of Life Aspects of Treatment,. _Care Rehabilitation_ 14, 749–757 (2005). Google Scholar * Gallagher, R., Marshall, A. P. & Fisher, M. J. Symptoms and

treatment-seeking responses in women experiencing acute coronary syndrome for the first time. _Heart Lung_ 39, 477–484 (2010). Article PubMed Google Scholar * King, R. Illness

attributions and myocardial infarction: the influence of gender and socio-economic circumstances on illness beliefs. _J. Adv. Nurs._ 37, 431–438 (2002). Article PubMed Google Scholar *

Jackson, D. et al. Women recovering from first-time myocardial infarction (MI): a feminist qualitative study. _J. Adv. Nurs._ 32, 1403–1411 (2000). Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar *

Manderbacka, K. Exploring gender and socioeconomic differences in treatment of coronary heart disease. _Eur. J. Public Health_ 15, 634–639 (2005). Article PubMed Google Scholar *

Koivunen, K., Isola, A. & Lukkarinen, H. Rehabilitation and guidance as reported by women and men who had undergone coronary bypass surgery. _J. Clin. Nurs._ 16, 688–697 (2007). Article

PubMed Google Scholar * Foà, C. & Artioli, G. Gender differences in myocardial infarction: health professionals’ point of view. _Acta Bio-medica: Atenei Parmensis_ 87, 7–18 (2016).

PubMed Google Scholar * Checa, C. et al. Living with advanced heart failure: a qualitative study. _PLoS ONE_ 15, e0243974 (2020). Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar *

Elbrond, P. G. et al. A qualitative study on men’s experiences of health after treatment for ischaemic heart disease. _Eur. J. Cardiovasc Nurs._ 21, 710–716 (2022). Article PubMed Google

Scholar * Vodopiutz, J. et al. Chest pain in hospitalized patients: cause-specific and gender-specific differences. _J. Women’s Health (Larchmt.)_ 11, 719–727 (2002). Article Google

Scholar * de Sousa, A. R. et al. Experiences of elderly men regarding acute myocardial infarction. _Acta Paul. Enferm._ 34, 1–8 (2021). Google Scholar * MacInnes, J. D. The illness

perceptions of women following acute myocardial infarction: implications for behaviour change and attendance at cardiac rehabilitation. _Women Health_ 42, 105–121 (2005). Article PubMed

CAS Google Scholar * Sallis, J. F., Owen, N. & Fisher, E. “Ecological models of health behavior. _‘Health Behav. Health Educ.’_ 4, 43–64 (2008). Google Scholar * Wieslander, I. et al.

‘Women’s experiences of how their recovery process is promoted after a first myocardial infarction: Implications for cardiac rehabilitation care’, _Int. J. Qualitative Studies Health

Well-Being_ 11, 1–N.PAG (2016). * ACCF/AHA/ACP 2009. Competence and training statement: a curriculum on prevention of cardiovascular disease. _J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. Sep_ 54, 1336–1363

(2009). Article Google Scholar * Roos, E. M. et al. Sex differences in symptom presentation in acute coronary syndromes: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. _J. Am. Heart Assoc._ 9,

e014733 (2020). Article Google Scholar * Gaziano, T. A., Bitton, A., Anand, S., Abrahams-Gessel, S. & Murphy, A. Growing epidemic of coronary heart disease in low- and middle-income

countries. _Curr. Probl. Cardiol._ 35, 72–115 (2010). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Crenshaw, K. W. _Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist

Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics_ 139–167 (University of Chicago Legal Forum, 1989). * Noureddine, S., Arevian, M., Adra, M. & Puzantian,

H. Response to signs and symptoms of acute coronary syndrome: differences between Lebanese men and women. _Am. J. Crit. Care_ 17, 26–35 (2008). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Allana, S.,

Khowaja, K., Ali, T. S., Moser, D. K. & Khan, A. H. Gender differences in factors associated with prehospital delay among acute coronary syndrome patients in Pakistan. _J. Transcultural

Nurs._ 26, 480–490 (2015). Article Google Scholar * Her Heart website, https://herheart.org/about-us/. Accessed 20 Feb 2023. * Go Red for Heart website, https://www.goredforwomen.org/en/.

Accessed 20 Feb 2023. * Page, M. J. et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. _PLoS Med._ 18, e1003583 (2021). Article PubMed PubMed Central

Google Scholar * Cooke, A., Smith, D. & Booth, A. Beyond PICO: the SPIDER tool for qualitative evidence synthesis. _Qual. Health Res._ 22, 1435–1443 (2012). Article PubMed Google

Scholar * Shaw, R. L. et al. Finding qualitative research: an evaluation of search strategies. _BMC Med Res Methodol._ 4, 5 (2004). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Long,

H. A., French, D. P. & Brooks J. M. Optimising the value of the critical appraisal skills programme (CASP) tool for quality appraisal in qualitative evidence synthesis _Res. Methods Med.

Health Sci._ 1, 31–42 (2020). * Butler, A., Hall, H. & Copnell, B. A guide to writing a qualitative systematic review protocol to enhance evidence‐based practice in nursing and health

care. _Worldviews Evid.-Based Nurs._ 13, 241–249 (2016). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Allsop, D. B. et al. Qualitative methods with Nvivo software: a practical guide for analyzing

qualitative data. _Psych_ 4, 142–159 (2022). Article Google Scholar * Thomas, J. & Harden, A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. _BMC

Med. Res. Methodol._ 8, 45 (2008). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author group would like to acknowledge the contribution of Ms

Rachel West, Liaison Librarian at Deakin University for their review of the electronic search strategy. This research was funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council of

Australia (grant number 2011209). AUTHOR INFORMATION AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Institute of Physical Activity and Nutrition, Deakin University, Burwood, VIC, Australia Helen Brown, Courtney

Brown & Ling Lee * School of Health and Social Development, Deakin University, Geelong, VIC, Australia James J. Lucas, Tiana Felmingham, Sean Randall & Kieva Richards * Institute

for Mental and Physical Health and Clinical Translation, Deakin University, Geelong, VIC, Australia Sarah Gauci & Adrienne O’Neil * National Centre for Farmer Health, Deakin University,

Victoria, Australia Susan Brumby * Western District Health Service, Hamilton, Australia Susan Brumby * School of Population Health, Curtin University, Perth, WA, Australia Crystal M. Y. Lee

& Dan Xu * La Trobe Rural Health School, La Trobe University, Bendigo, VIC, Australia George Mnatzaganian * Institute for Health Transformation, Deakin University, Burwood, VIC,

Australia Suzanne Robinson, Lan Gao & Adrienne O’Neil * School of Psychology and Public Health, La Trobe University, Bundoora, Australia James Boyd * Curtin Medical School, Faculty of

Health Sciences, Curtin University, Perth, WA, Australia Dan Xu * First Affiliated Hospital, Sun Yat-Sen University, Guangzhou, China Dan Xu * The University of New South Wales, Kensington,

NSW, Australia Ling Lee * Faculty of Health, Deakin University, Melbourne, Australia Rachel R. Huxley Authors * Helen Brown View author publications You can also search for this author

inPubMed Google Scholar * James J. Lucas View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Sarah Gauci View author publications You can also search for

this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Courtney Brown View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Susan Brumby View author publications You can also

search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Tiana Felmingham View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Crystal M. Y. Lee View author

publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Sean Randall View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * George

Mnatzaganian View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Suzanne Robinson View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed

Google Scholar * Lan Gao View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * James Boyd View author publications You can also search for this author

inPubMed Google Scholar * Adrienne O’Neil View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Dan Xu View author publications You can also search for this

author inPubMed Google Scholar * Kieva Richards View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Ling Lee View author publications You can also search

for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Rachel R. Huxley View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CONTRIBUTIONS All authors made substantial

contributions to either the conception of the work, the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data, and helped draft, revise and approve the final version. All authors agree to be

accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of the work. H.B., S.G. and J.L. wrote the main manuscript text and conducted the data

collection for the review. All authors reviewed the manuscript. CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to Helen Brown. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS The authors declare no competing

interests. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION PUBLISHER’S NOTE Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. SUPPLEMENTARY

INFORMATION SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS OPEN ACCESS This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing,

adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons

licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a

credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted

use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Reprints and permissions ABOUT

THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Brown, H., Lucas, J.J., Gauci, S. _et al._ A systematic review of healthcare experiences of women and men living with coronary heart disease. _npj Womens

Health_ 2, 40 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44294-024-00043-x Download citation * Received: 29 April 2024 * Accepted: 25 October 2024 * Published: 22 November 2024 * DOI:

https://doi.org/10.1038/s44294-024-00043-x SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not

currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative