Play all audios:

ABSTRACT During chronic kidney disease (CKD) there is a dysregulation of extracellular matrix (ECM) homeostasis leading to renal fibrosis. Lysosomal proteases such as cathepsins (Cts)

regulate this process in other organs, however, their role in CKD is still unknown. Here we describe a novel role for cathepsins in CKD. CtsD and B were located in distal and proximal

tubular cells respectively in human disease. Administration of CtsD (Pepstatin A) but not B inhibitor (Ca074-Me), in two mouse CKD models, UUO and chronic ischemia reperfusion injury, led to

a reduction in fibrosis. No changes in collagen transcription or myofibroblasts numbers were observed. Pepstatin A administration resulted in increased extracellular urokinase and collagen

degradation. _In vitro_ and _in vivo_ administration of chloroquine, an endo/lysosomal inhibitor, mimicked Pepstatin A effect on renal fibrosis. Therefore, we propose a mechanism by which

CtsD inhibition leads to increased collagenolytic activity due to an impairment in lysosomal recycling. This results in increased extracellular activity of enzymes such as urokinase,

triggering a proteolytic cascade, which culminates in more ECM degradation. Taken together these results suggest that inhibition of lysosomal proteases, such as CtsD, could be a new

therapeutic approach to reduce renal fibrosis and slow progression of CKD. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS LYSYL OXIDASE INHIBITORS ATTENUATE CYCLOSPORIN A-INDUCED NEPHROPATHY IN

MOUSE Article Open access 14 June 2021 MATRIX METALLOPROTEINASE-10 PROMOTES KIDNEY FIBROSIS BY TRANSACTIVATING Β-CATENIN SIGNALING Article Open access 17 May 2025 ANTIFIBROTIC EFFECT OF

NOVEL NEUTROPHIL GELATINASE-ASSOCIATED LIPOCALIN INHIBITORS IN CARDIAC AND RENAL DISEASE MODELS Article Open access 28 January 2021 INTRODUCTION The worldwide prevalence of chronic kidney

disease (CKD) is estimated to be between 8–16% and is predicted to rise due to the ageing population and an increase in the incidence of diabetes and hypertension1. There are many causes of

CKD including ischemic, toxic and infectious insults to the kidney and genetic, endocrine and immunological diseases. Progression of CKD results in end-stage renal disease (ESRD) and organ

failure. Treatments to stop or slow the progression of CKD to ESRD are currently very limited2, with increasing numbers of patients requiring life-long dialysis or transplantation.

Glomerulosclerosis and tubulointerstitial fibrosis are two main histological features of CKD. After kidney injury there is a physiological wound healing response to restore normal function

and tissue homeostasis. However, repetitive insults or dysregulation of this response leads to excessive, pathological deposition of extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins such as fibrillar

collagens (mainly type I and III), fibronectin and laminins. ECM deposition, crosslinking, turnover and degradation are finely regulated _in vivo_ by proteases, transglutaminases, lysil

oxidases and their inhibitors. The study of protease biology is challenging at many levels: their regulation is complex occurring during gene transcription, cell trafficking, extracellular

secretion, activation of latent forms and recycling; their substrate specificity and preference can vary from _in vitro_ to _in vivo_ and diseased to non-diseased tissues and finally there

is a high degree of redundancy amongst different proteases, which can lead to complex compensatory mechanisms. There are two main families of proteases which have been implicated in the

progression of renal fibrosis, metalloproteinases (MMP)3 and serine proteases4. However, the role of other proteases such as lysosomal cathepsins (Cts) is poorly understood in the context of

renal fibrosis, despite playing an important role in other fibrotic diseases such as liver (CtsB), lung (CtsK) and heart (CtsL) fibrosis. CtsB inactivation attenuates hepatic damage5 and

reduces scarring6,7 in several experimental models of liver fibrosis. In contrast in bleomycin lung fibrosis model, CtsK deficient mice have a worse outcome than wild type mice8, while

transgenic overexpressing CtsK mice show a reduction in lung fibrosis9. Similarly, CtsL knock-out mice develop spontaneous age-related cardiac fibrosis10 while overexpression of human CtsL

in a murine model of cardiac hypertrophy leads to an improvement of cardiac function and fibrosis11. Despite the evidence in other organs the role of lysosomal cathepsins in kidney fibrosis

remains unclear. Therefore the aim of this study was to analyse the role of cathepsins in renal fibrosis. Here we describe a novel role for CtsD in kidney fibrosis. Screening of human kidney

biopsies showed stronger CtsD staining in kidneys with tubular damage, localizing CtsD mainly in cytosolic vesicles of distal tubules. Analysis of aspartyl and cysteine cathepsins

expression in mouse obstructive nephropathy showed an increase in CtsD and B but not L. Pharmacological inhibition of CtsD but not CtsB led to a reduction of kidney fibrosis in two different

models of CKD, unilateral ureteric obstruction (UUO) and chronic ischemia reperfusion injury (IRI). Our _in vivo_ and _in vitro_ observations support a novel mechanism of action by which

inhibition of CtsD leads to an impairment of lysosomal recycling increasing the amount of active proteases available in the extracellular space, such as UPA. Active UPA could then regulate

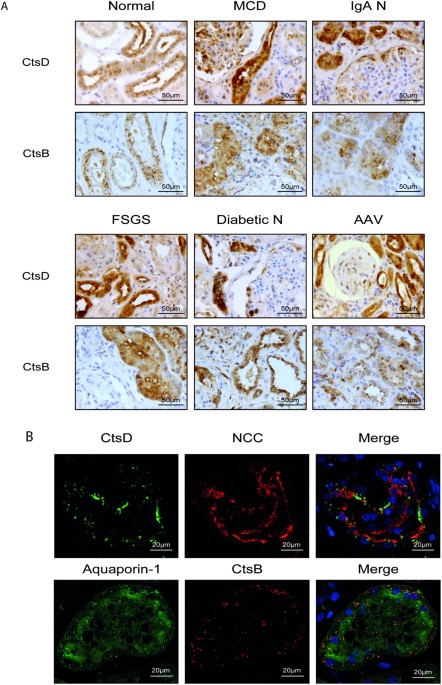

and activate plasmin, enhancing ECM remodelling, ultimately reducing renal fibrosis. RESULTS CTSD AND B ARE DIFFERENTIALLY EXPRESSED IN DISTAL AND PROXIMAL TUBULES RESPECTIVELY DURING HUMAN

KIDNEY DISEASE We determined the expression of CtsD or CtsB in normal human kidney and a range of human kidney diseases: minimal change disease (MCD), IgA nephropathy (IgA N), focal

segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS), diabetic nephropathy (Diabetic N) and anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) associated vasculitis (AAV). Analysis by a renal histopathologist

identified a common expression pattern for all the diseases analysed, with CtsD or CtsB mainly expressed in cytosolic vesicles from distal or proximal tubular cells respectively (Fig. 1A).

Interestingly, areas with a greater number of damaged tubules had more CtsD expression than unaffected areas or normal kidneys. No differences in CtsB expression were detected between normal

and diseased kidneys (Fig. 1A). Of note, both CtsD and B were also detected in some podocytes and glomerular crescents. The distal or proximal tubular distribution of CtsD or B was also

confirmed by confocal microscopy using thiazide-sensitive NaCl co-transporter (NCC) and aquaporin-1 as a distal or proximal tubular markers respectively (Fig. 1B). Based on these

observations, CtsD could potentially play a role in tubular injury. RENAL CTSD AND B EXPRESSION IS INDUCED IN OBSTRUCTIVE NEPHROPATHY We next analysed aspartyl CtsD and cysteine CtsB and L

expression in mice kidneys after 7 days Unilateral Ureteric Obstruction (UUO). CtsD, L and cysteine cathepsin inhibitors, cystatin B and C, mRNA expression were significantly increased in

UUO kidneys compared to contralateral unobstructed kidneys, however, CtsB mRNA expression did not change (Fig. 2A). Cortical fibrosis in UUO kidneys was confirmed by morphometric analysis of

Sirius Red and α-SMA (Fig. 2B,C). Although cathepsins are regulated at the transcriptional level, the main step in regulating their activity occurs in the lysosomes where cathepsins are

stored as inactive zymogens before being cleaved into the active protease12. Pro- and mature CtsD as well as mature CtsB were increased in UUO kidneys. In contrast mature CtsL decreased in

diseased kidneys (Fig. 2D). To define the time course of CtsD upregulation, protein and mRNA levels were measured 5, 7 and 10 days after UUO induction. Both protein and gene expression were

significantly upregulated by day 5 UUO with further increase by day 7. CtsD mRNA expression rose further by day 10 while protein expression plateaued after day 7 (Supplementary Fig. S1A,B).

Therefore, during UUO there is a differential regulation of aspartyl and cysteine cathepsins with an increase of CtsD and B protein expression and processing into mature forms and a decrease

in mature CtsL. PEPSTATIN A REDUCES KIDNEY FIBROSIS IN TWO DIFFERENT MODELS OF CHRONIC KIDNEY DISEASE Active CtsD and B act as pro-fibrogenic enzymes in liver fibrosis6. To investigate

whether the increase in active enzymes was playing a role in the development of kidney fibrosis, Pepstatin A (CtsD inhibitor) or Ca074-Me (CtsB inhibitor) were administered three times a

week for 15 days following UUO. To be more representative of human disease, surgery was performed and renal injury was allowed to develop for 5 days before starting treatment, by which stage

an increase in α-SMA and Col1A1 gene expression was already evident in untreated UUO mice (Supplementary Fig. S1C,D). Consistent with Fig. 2D, CtsD activity was significantly increased in

injured kidneys and reduced back to control levels by Pepstatin A administration. Ca074-Me had no effect on CtsD activity assessed by fluorimetric activity in kidney lysates (Fig. 3A). The

inhibitory effect of Ca074-Me on CtsB activity was demonstrated _in vivo_ in 10 days UUO kidneys by IVIS analysis using a CtsB activable fluorescent probe (Fig. 3B). Morphometric analysis of

Sirius Red, collagen III and IV cortical staining, showed an increase in fibrosis and thickening of the tubular basal membrane in injured kidneys (Fig. 3C–E). Ca074-Me administration had no

effect over Sirius Red or collagen IV and only a moderate effect over collagen III. However, Pepstatin A treatment significantly reduced cortical accumulation of Sirius Red, collagen III

and IV in fibrotic kidneys (Fig. 3C–E). The effect of Pepstatin A on kidney fibrosis was confirmed in a second model of chronic ischemia reperfusion injury (IRI) (35 minutes of ischemia

followed by 28 days of reperfusion). Pepstatin A was again administered from 5 days post-surgery. CtsD activity was significantly increased in IRI kidneys versus control and Pepstatin A

treatment reduced this levels back to normal control as assessed by fluorimetric activity in kidney lysates (Fig. 4A). In agreement with the UUO results, Pepstatin A effectively reduced

cortical accumulation of Sirius Red, collagen III and IV in IRI kidneys (Fig. 4B–D). Thus, CtsD but not B inhibition lead to a reduction in kidney fibrosis in two different models of chronic

kidney disease. PEPSTATIN A REDUCES KIDNEY FIBROSIS DUE TO AN INCREASE IN COLLAGEN DEGRADATION The reduction in collagen deposition with Pepstatin A treatment could be explained by changes

in ECM gene transcription rate, myofibroblasts numbers or ECM degradation rate. Transcript levels of Col1A1, Col3A1 and Col4A1 were significantly increased in fibrotic kidneys in both

models, however, the increase was not affected by Pepstatin A treatment (Fig. 5A–F). Pepstatin A treatment did not affect the cortical area occupied by myofibroblasts, determined by α-SMA

immunostaining, in UUO or IRI kidneys (Fig. 6A,B). Finally, collagenolytic activity was analysed by _in situ_ collagen I zymography in UUO cryosections and C3M peptide ELISA13 in sham and

IRI serum. _In situ_ zymography assesses cleavage of collagen I by using a specific DQTM collagen I fluorescein conjugated substrate. When this substrate is intact its signal is quenched by

the close proximity of the dyes and only after enzyme-driven hydrolysis, there is an increase in fluorescence intensity. C3M is a collagen III proteolytic fragment, also called neo-peptide,

derived from MMP mediated enzymatic cleavage. These peptides can be released from different tissues into circulation and are currently under study as possible biomarkers to assess collagen

degradation in different diseases14. Indeed, C3M has already been reported as a marker for experimental renal fibrosis15. Both methods showed higher collagenolytic activities in Pepstatin A

treated fibrotic mice (Fig. 6C,D). In summary, Pepstatin A effectively reduced fibrosis in two independent models of kidney fibrosis by enhancing collagenolytic activity as opposed to

changes in the collagen synthesis or myofibroblast numbers. PEPSTATIN A ACTIVATES THE UROKINASE PLASMINOGEN ACTIVATOR SYSTEM According to our results CtsD plays a pro-fibrogenic role in

kidney fibrosis, as its inhibition enhances collagen degradation and reduces fibrosis. Cathepsins can enhance ECM turnover through activation of other proteases16. The urokinase plasminogen

activator system plays a role in CKD by directly degrading ECM proteins and activating MMPs17. UPA protein expression was induced in fibrotic kidneys compared to the contralateral controls

in UUO with a further increase after Pepstatin A administration (Fig. 7A). Plasminogen/casein zymography using kidney lysates from the IRI model confirmed the UUO results showing an increase

in UPA activity in fibrotic kidneys from mice treated with Pepstatin A compared to vehicle (Fig. 7B,C). Urokinase and its receptor (UPAR) are known to be in part regulated through

endo/lysosomal recycling once UPA has bound its inhibitor PAI17. In vehicle treated fibrotic kidney (UUO and IRI) dual confocal immunofluorescence demonstrated co-localization of CtsD and

UPA in a vesicle like pattern in the cytosol of tubular cells (Fig. 7D; Supplementary Fig. S2). Further confocal analysis of lysosomal-associated membrane protein-2 (LAMP-2), as a lysosomal

marker and UPA confirmed the vesicle like pattern as lysosomes (Fig. 7D; Supplementary Fig. S2). In summary, in our CKD models Pepstatin A is able to induce an increase in active urokinase.

In addition to this, CtsD and UPA co-localize in lysosomes in fibrotic kidneys, pointing towards a possible interaction between UPA and CtsD within the lysosomes. Our results suggest that

affectation of UPA endo/lysosomal recycling by CtsD inhibition, could lead to an increase of extracellular UPA, which could then modulate the activation of plasmin and potentially MMPs18,19

both of which enhance ECM degradation. CTSD INHIBITION ENHANCES UPA SECRETION BY IMPAIRING ITS ENDO/LYSOSOMAL RECYCLING Our results show co-localization of CtsD and UPA in lysosomes (Fig.

7D; Supplementary Fig. S2). UPA/UPAR complex is known to be recycled through endo/lysosomal internalization17. To investigate whether only CtsD or also CtsB has an effect on UPA lysosomal

recycling, we treated the human tubular epithelial cell line HKC-8 with Pepstatin A and Ca074-Me. As expected only Pepstatin A but not Ca074-Me was able to inhibit CtsD activity

(Supplementary Fig. S3A). UPA WB of concentrated media revealed an increase in extracellular UPA after Pepstatin A, but not Ca074-Me treatment (Fig. 8A). Plasminogen/casein zymography

confirmed an enhancement of UPA activity by Pepstatin A showing three different isoforms of UPA, 55, 40 and 33 KDa20 (Fig. 8B). In agreement, CtsD siRNA transfection also showed an increased

in UPA secretion into the extracellular media (Fig. 8C). Next we assessed whether Pepstatin A enhanced UPA secretion by affecting its endo/lysosomal recycling through clathrin-mediated

endocytosis21. We analysed the UPA cellular distribution in primary human distal tubular epithelial cells (NCC+, cytokeratin-19+, collagen-1−, Supplementary Fig. S3B,C). We demonstrated

co-localization of AP2-μ1 adaptor protein, which is essential for the clathrin vesicle formation, with UPA, suggesting that UPA was being endocytosed through the clathrin dependent pathway

in hDTC (Fig. 8D). In order to impair endo/lysosomal activity we used the endo/lysosomal inhibitor, chloroquine (CQ). As with Pepstatin A treatment, HKC-8 cells treated with CQ showed

increased levels of active UPA into the extracellular media by plasminogen/casein zymography (Fig. 8E). To investigate whether CQ had a similar effect to Pepstatin A _in vivo_, UUO was

performed and animals were treated with Pepstatin A, CQ or vehicle. CQ endo/lysosomal inhibition is in part due to its ability to prevent endo/lysosomal acidification. This rise in pH will

result in reduced lysosomal enzyme activity. CtsD activity in UUO kidney lysates from mice treated with CQ showed significantly less CtsD activity than vehicle treated UUO kidneys

(Supplementary Fig. S3D). Consistent with our _in vitro_ data, CQ was able to reduce cortical fibrosis to a similar level as Pepstatin A assessed by Sirius Red staining (Fig. 8F). Taken

together our results suggest that Pepstatin A enhances UPA secretion by impairing its lysosomal recycling. DISCUSSION In this study we clearly demonstrate that inhibition of aspartyl

cathepsin D leads to a reduction in interstitial fibrosis in two models of renal disease. The number of patients with CKD is increasing and some of these patients will progress onto end

stage renal disease and face life-long dialysis or organ transplant. Treatment options for patients with progressive disease are limited, thus there is an urgent need to find new therapeutic

targets that could lead to drug development. Interstitial fibrosis is almost invariably seen in patients with progressive CKD. Dysregulation of extracellular matrix (ECM) homeostasis leads

to a gradual replacement of the healthy nephrons by electrondense fibrotic ECM. Proteases play a crucial role in regulating this process; however, our knowledge of proteases biology and

function in CKD is still very limited. Lysosomal proteases have been implicated in the pathogenesis of fibrotic disease in the liver, (CtsB and D)6,7 lung, (CtsK)8,9 and heart, (CtsL)10,11

but very little is known about their function in renal disease. The only reports relate to the role of cysteine but not aspartyl cathepsins (CtsD family group). There is decreased activity

in the kidney of the cysteine cathepsins B, H and L accompanied by an increase in their urinary secretion in rat polycystic kidney disease22, puromycin induced nephrosis23 and rat and human

diabetic nephropathy24,25. However, not all cysteine cathepsins decrease during proteinuric kidney disease and CtsL26 increases in proximal tubular cells and podocytes. Therefore, the role

of cathepsins is currently far from understood, pointing towards a cell and disease specific function. Screening of a panel of human renal biopsies show for the first time the expression of

CtsD and B in distal and proximal tubular cells respectively in human renal disease (Fig. 1A,B). In agreement with Goto _et al.’s_27 observations in human normal kidney, CtsD is mainly

expressed in distal convoluted tubules. Our results point towards an increase of CtsD expression in areas of tissue damage with no change in CtsB expression. The number of patients screened

in our study was insufficient to draw statistical conclusions and further investigations will be needed in a bigger cohort to determine an association between level of CtsD expression and

disease outcome. To investigate the role of CtsD and B in CKD we used an aspartyl or cysteine protease inhibitor, Pepstatin A or Ca074-Me, in a murine CKD model, UUO. Pepstatin A but not

Ca074-Me diminished collagen accumulation and thickening of the tubular basement membrane (Fig. 3C–E) with no effect on collagen transcription (Fig. 5A–C) or myofibroblast (Fig. 6A) numbers.

Pepstatin A effects on fibrosis were reproduced in a second model of CKD, 35 minutes/28 days IRI (Figs 4B–D,5D,F and 6B). Our results suggest that Pepstatin A reduces fibrosis by increasing

collagen I and III degradation (Fig. 6C,D). Despite Pepstatin A being the best inhibitor against CtsD available and in contrast to Ca074-Me, which is a rather specific inhibitor against

CtsB28, Pepstatin A can also affect other proteases of the same family, thus additional effects on other proteases cannot be excluded. Indeed, this may contribute to the outcome of our

study, as redundancy and compensatory mechanisms12 are common problems when targeting only one member of a protease family. CtsD knock-out mice die approximately 26 days after birth due to

neurological disorders29 replicating human deficiency30,31. In our models Pepstatin A did not completely block CtsD activity, achieving a reduction back to physiological levels (Figs 3A and

4A), avoiding possible undesirable secondary effects. Cathepsins can indirectly modulate ECM turnover by affecting other proteases. We investigated the relationship between CtsD and UPA as

an example of how CtsD can affect extracellular protease activity. Urokinase (UPA) was upregulated in fibrotic kidneys after the treatment with Pepstatin A (Fig. 7A–C). _In vitro_,

extracellular UPA was increased in human tubular epithelial cells treated with CtsD but not B inhibitor and siRNA against CtsD (Fig. 8A–C). UPA belongs to the urokinase plasminogen activator

system, the role of which in CKD remains controversial17,32,33. UPA is anti-fibrotic in lung34 and liver35 whereas surprisingly no difference in the severity of UUO was observed in UPA

knock-out mice36. UPA is secreted extracellularly and activated upon binding to its surface receptor, UPAR. Then activates other proteins, preferentially plasminogen into plasmin, which can

directly degrade ECM proteins37,38,39 and also activates MMPs18,19, triggering further ECM degradation. Despite several reports in the literature of a direct link between UPA, plasmin and

MMP activation, further work is required to demonstrate a link to CtsD. PAI-1, UPA’s natural inhibitor, covalently binds to the UPA:UPAR complex inhibiting UPA’s enzymatic activity. The

UPA:UPAR:PAI-1 complex is then rapidly internalized upon binding to LDL receptor-related protein-1 (LRP-1) through clathrin dependent endocytosis pathway into the lysosomes21. There UPA and

PAI-1 are degraded and UPAR is recycled back to the cell surface. We confirmed localization of UPA in clathrin endosomal vesicles by co-localizing UPA with AP2-μ1 adaptor protein, which is

an essential protein for the clathrin-coated pit formation, in hDTC (Fig. 8D). We also proved co-localization of CtsD and UPA within the lysosomes in fibrotic kidneys (Fig. 7D, Supplementary

Fig. S2). Previous work by van Kasteren SI _et al._ support our hypothesis of Pepstatin A affecting endo/lysosomal recycling as they described EGFR clathrin dependent endo/lysosomal

degradation being impaired by a cystatin-pepstatin inhibitor (CPI)40. In order to further confirm a link between lysosomal degradation and the increase in UPA, we used chloroquine (CQ) as

endo/lysosome inhibitor. Both Pepstatin A and CQ had similar effects _in vitro_, increasing the active extracellular UPA (Fig. 8E). In addition, CQ administration in the UUO model mimicked

the effect seen with Pepstatin A administration, reducing collagen accumulation and fibrosis (Fig. 8F). In summary, here we report for the first time the distribution of CtsD and B in human

renal disease and show the effect of their inhibition in two mouse models of renal fibrosis. We propose a novel mechanism by which CtsD inhibition by Pepstatin A leads to an increase in

extracellular protease activity, in particular UPA, due to altered lysosomal recycling. This can trigger a proteolytic cascade activating first plasminogen into plasmin and culminating

possibly with the regulation and activation of MMPs18,19. Both plasmin37,38,39 and MMPs are able to degrade ECM proteins causing a net reduction in fibrosis. This situation can be further

sustained by a positive feedback loop, as plasmin is also able to activate UPA20. Our model does not exclude the regulation by CtsD of other proteases that might be recycled through the

lysosomal pathway and further investigation will be needed to clarify this. This work opens new and exciting prospects for the treatment of CKD by targeting lysosomal proteases. METHODS

REAGENTS CtsD fluorimetric activity assay was from Abcam. Pepstatin A, Chloroquine were from Sigma. Ca074-Me was from PeptaNova. Cat B 750 FAST Fluorescent Imaging Agent was from Perkin

Elmer. DQ™ Collagen, type I from Bovine Skin, Fluorescein Conjugate was from Invitrogen Life Technologies. Human Plasminogen was from Biopur. Avidin/Biotin blocking kit, Citric acid based

antigen unmasking solution, Vectastain Elite ABC Reagent, DAB peroxidase substrate kit, Vectashield mounting medium were purchased from Vector Laboratories. Unless otherwise reported all

other reagents were from Sigma-Aldrich. UNILATERAL URETER OBSTRUCTION (UUO) MODEL OF KIDNEY FIBROSIS All the animal studies were done in accordance to the UK Home Office regulations and

under its approval (licence 60/4521). Left proximal ureter ligation was performed in 8–10 week C57BL/6 females. Right kidneys were used as controls. Animals were culled at 5, 7, 10 and 15

days post-surgery. 15 days UUO mice received intraperitoneal injections of vehicle, Pepstatin A (20 mg/Kg), Ca074-Me (10 mg/Kg) or Chloroquine (20 mg/Kg) from day 5 post-surgery three times

a week up to 15 days. A minimum of 6 animals were used in each experimental group. CHRONIC ISCHEMIA REPERFUSION (IRI) MODEL OF KIDNEY FIBROSIS Ischemia was achieved by clamping the left

renal pedicle for 35 minutes in 8–10 week C57BL/6 females. After 35 minutes the clamp was removed and the kidney reperfused for 28 days. Right kidneys were used as controls. Vehicle and

Pepstatin A (20 mg/Kg) were administered by intraperitoneal injection from day 5 post-surgery three times a week up to 28 days. A minimum of 6 animals were used in each experimental group.

CATHEPSIN B _IN VIVO_ ACTIVITY BY IVIS IMAGING For the IVIS analysis Cathepsin B Prosense 750 probe was injected intravenously according to manufacturer´s instructions in 10 days UUO mice.

After 7 hours animals were anesthetized with isoflurane and scanned using 745 nm excitation and 800 nm emission wavelengths with an IVIS Spectrum CT (Caliper Life Sciences). Animals were

scanned before injection and the background was subtracted. Data was analysed using Living Image 4.2 software, regions of interest (ROI) were drawn and the average of the Total Radiant

Efficiency [p/s]/[μW/cm2] was calculated per ROI. CELL CULTURE HKC-8 cells41 or NRK-49F (ATCC® CRL 1570™) were cultured in 1:1 Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s: F12 medium or DMEM supplemented

with 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 2 mM L-glutamine, 5% FBS and maintained at 37 °C at an atmosphere of 5% CO2. SIRNA TRANSFECTION During treatment cells were cultured in 0%

FBS. Cells were transfected with 50 nM Scramble or 50 nM CtsD siRNA using INTERFERin (Polyplus) according to manufacturer’s instructions for 48 hrs. After that, media was collected and cell

lysates were performed. ISOLATION OF HUMAN PRIMARY DISTAL TUBULAR CELLS (HDTC) Human kidneys cells were isolated from adult kidneys after surgical resection in accordance to the Research

Ethics Committee guidelines and approval granted by the NRES Committee East Midlands-Derby (REC ref. 13/EM/0311), subject to patient consent. Briefly, after removing the kidney capsule, the

cortex was mince and digested with 1 mg/ml collagenase IV for 60 minutes at 37 °C. Digested tissue was passed through a 40 μm cell strainer and centrifuged at 1200 rpm. Pellet was

resuspended in RPMI, loaded in a two layer Percoll gradient (50%, 24.6%) and centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 25 minutes at 4 °C. Top layer containing DTC was washed twice in RPMI at 1200 rpm.

DTC were seeded and maintained in DMEM/F-12, GlutaMAX™ supplemented with 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 2 mM L-glutamine, 10% FBS and maintained at 37 °C at an atmosphere of 5%

CO2. Cells were used in between passage 2 and 3. Phenotypic characterisation of the hDTC by WB confirmed they expressed thiazide-sensitive NaCl cotransporter (NCC)+ and cytokeratin-19+ but

not Collagen 1−. Conversely, the rat kidney fibroblast cell line NRK-49F was positive for Collagen 1+ but did not express NCC− or cytokeratin-19− (Supplementary Fig. S3B). Microvilli were

seen on scanning electron microscopy (Supplementary Fig. S3C). CtsD expression in hDTC was confirmed by WB (Supplementary Fig. S3B). ELECTRON SCANNING MICROSCOPY hDTC were cultured in 13 mm

glass coverslips until full confluence, when they were fixed with 2% glutaraldehyde in Sorenson’s Phosphate Buffer overnight at 4 °C. Once fixed, they were washed and transferred into 100%

ethanol and critically point dried. The cells were then gold coated and scanned in a VEGA3 TESCAN microscope. IMMUNOHISTOCHEMISTRY IN MOUSE AND HUMAN SAMPLES Immunohistochemistry was

performed in 4 μm formalin-fixed kidney slides. Sections were deparaffinised and endogenous peroxidase was blocked with 2% hydrogen peroxide/methanol solution. Antigen retrieval was

performed according to Supplementary Table S1. Endogenous avidin and biotin were blocked. Blocking solution and primary antibody was added overnight. After the addition of the secondary

biotinilated antibody and ABC, sections were developed with DAB, counterstain with Mayer’s haematoxylin and mounted. For α-SMA, Collagen III and Collagen IV image analysis was performed at

200X using Nikon Eclipse Upright microscope and NIS-Elements BR Analysis software from Nikon. At least 10 random fields of cortex were analysed per kidney. For CtsD and B, human sections

were assessed by an expert histopathologist (KMW). A minimum of three different patient biopsies were stained per disease. STUDY APPROVAL FOR HUMAN SAMPLES Access to patient biopsies was

approved by the NRES Committee East Midlands-Derby Research Ethics Committee (REC ref. 13/EM/0311). Normal, Minimal Change Disease, IgA nephropathy, FSGS, Diabetic nephropathy and ANCA

associated vasculitis biopsy samples were taken under full ethical approval and patient consent, in accordance to the approved guidelines. DUAL IMMUNOFLUORESCENCE For sections, 4 μm

formalin-fixed kidney tissue sections were deparaffinised. After microwave citrate saline antigen retrieval, permeabilization with 0.25% Triton X-100 was performed. Sections were then

blocked with 5% BSA and primary antibodies, Thiazide-Sensitive NaCl Cotransporter (NCC), CtsD or LAMP-2 and UPA were applied in 1% BSA overnight. For coverslips, hDTC were cultured in glass

coverslips, fixed with formalin and permeabilized with 0.1% saponine/0.5% BSA. After blocking with 3% BSA, primary antibodies AP2-μ1 and UPA were applied for 90 minutes. After washing, the

secondary antibodies were sequentially added, donkey anti-rabbit Alexa 594 and anti-goat-FITC or goat anti-rat IgG Alexa 488. An extra blocking step with 20% rabbit serum was added between

secondaries for the CtsD/UPA and the AP2-μ1/UPA dual stainings. Sections were finally mounted with ProLong® Diamond DAPi conjugated mounting medium (Invitrogen) and analysed using a Leica

TCS SP2 confocal microscope. Pictures were taken sequentially at 400X or 630X oil. 1.8 electronic zoom was made of a region of interest. 4 images of 1 μm slice each were acquired per section

or 13 images of 0.5 μm slice each were acquired per coverslip. Image analysis was performed using Image J software. A detailed list of antibodies is provided in Supplementary Table S2.

PLASMINOGEN/CASEIN ZYMOGRAPHY Briefly, whole kidney lysates or concentrated medias mixed with 2× Laemmli buffer (Bio-Rad) were resolved in 10% acrylamide/bis-acrylamide gel containing 13

μg/mL of human plasminogen with EACA and 1 mg/mL of β-casein. Gel was washed twice with 2.5% Triton X-100 and incubated for 12–33 hrs at 37 °C in 0.1 M glycine soluction at pH: 8.0. The gel

was stained with 0.2% Comassie R-250/ 10% acetic acid/45% methanol solution for 1 hr and distained with 7% acetic acid/ 40% methanol until optimal band resolution. _IN SITU_ ZYMOGRAPHY

Kidney cryostat sections of 6 μm thickness where coated with low gelling temperature agarose containing 0.1 mg/mL DQ™ Collagen, type I fluorescein conjugated and 1 μg/mL of DAPI. Agarose was

left to set in the fridge for 2 hrs. Then slides were incubated at 30 °C for 20 hrs. Fluorescence was detected using a Zeiss AxioImager microscope, 15 random pictures were taken at 200X.

Fluorescent intensity was analysed using Image J software. CTSD ACTIVITY ASSAY Cathepsin D activity was determined using a fluorescence-based assay “Cathepsin D activity assay” from Abcam.

This assay utilizes the preferred cathepsin-D substrate sequence GKPILFFRLK(Dnp)-D-R-NH2) labelled with MCA. 0.1–10 μg of protein were used per assay according to manufacturer’s

instructions. Assay plates were incubated at 37 °C and readings were performed in a fluorometer at 355 nm excitation and 520 emission for 2 hours. Results are expressed as a slope of

fluorescence emission after 2 hours per μg of protein. SERUM C3M ENZYME-LINKED IMMUNOSORBENT ASSAY The specific MMP-generated neo-epitope of the collagen type III alpha 1 chain (C3M) was

detected by competitive ELISA using a specific monoclonal antibody. Assay was performed as previously described13. SIRIUS RED STAINING Kidneys were fixed with formalin, embedded in paraffin

and sections of 4 μm were routinely stained with 0.1% Sirius Red following standard procedures. Image analysis was performed as described in the immunohistochemistry section. SDS PAGE AND

IMMUNOBLOTTING Total kidney or cell lysates were prepared with radioimmune precipitation assay buffer (RIPA). Concentrated medias were prepared using Amicon Ultra-0.5 Centrifugal Filters

from Millipore. 10–30 μg of protein were fractionated in 8–12% SDS-PAGE and transferred into nitrocellulose membranes. Blots were incubated with 5% non-fatty dry milk or BSA in 0.1%

TBS-Tween. Membranes were incubated overnight with primary antibodies, anti-Cathepsin D, anti-UPA, anti-α-SMA and anti-GAPDH. Membranes were washed with TBS-Tween, incubated with secondary

HRP conjugated antibodies and develop with ECL (Thermo scientific). A detailed list of antibodies is provided in Supplementary Table S2. RNA ISOLATION AND REAL TIME PCR RNA from kidney

tissue was extracted with TriReagent. Briefly, RNA was precipitated from the aqueous phase with isopropanol and washed with 70% ethanol. Purity was assessed using a Nanodrop and cDNA

synthesis was performed (Promega RT kit). Real time PCR was performed with SYBR Green JumpStart ready mix according to manufacturer’s instructions. Data was calculated using ∆∆Ct and 18S was

used as a housekeeping gene. Data is plotted against vehicle control group. Primer sequences used are reported in the Supplementary Table S3. STATISTICS Results are expressed as mean ± SEM

unless otherwise stated in the figure legend. All p values were calculated using one way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s test or two tailed unpaired student’s t-test. _*P_ ≤ 0.05 or _**P_ ≤

0.01 was considered statistically significant. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION HOW TO CITE THIS ARTICLE: Fox, C. _et al._ Inhibition of lysosomal protease cathepsin D reduces renal fibrosis in murine

chronic kidney disease. _Sci. Rep._ 6, 20101; doi: 10.1038/srep20101 (2016). REFERENCES * Jha, V. et al. Chronic kidney disease: global dimension and perspectives. Lancet 382, 260–272

(2013). Article PubMed Google Scholar * National Kidney Foundation. KDOQI Clinical Practice Guideline for Diabetes and CKD: 2012 Update. Am J Kidney Dis 60, 850–886 (2012). * Tan, R. J.

& Liu, Y. Matrix metalloproteinases in kidney homeostasis and diseases. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 302, F1351–1361 (2012). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Eddy,

A. A. Serine proteases, inhibitors and receptors in renal fibrosis. Thromb Haemost 101, 656–664 (2009). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Moles, A., Tarrats, N.,

Fernandez-Checa, J. C. & Mari, M. Cathepsin B overexpression due to acid sphingomyelinase ablation promotes liver fibrosis in Niemann-Pick disease. J Biol Chem 287, 1178–1188 (2012).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Moles, A., Tarrats, N., Fernandez-Checa, J. C. & Mari, M. Cathepsins B and D drive hepatic stellate cell proliferation and promote their

fibrogenic potential. Hepatology 49, 1297–1307 (2009). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Canbay, A. et al. Cathepsin B inactivation attenuates hepatic injury and fibrosis during

cholestasis. J Clin Invest 112, 152–159 (2003). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Buhling, F. et al. Pivotal role of cathepsin K in lung fibrosis. Am J Pathol 164,

2203–2216 (2004). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Srivastava, M. et al. Overexpression of cathepsin K in mice decreases collagen deposition and lung resistance in response

to bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis. Respir Res 9, 54 (2008), 10.1186/1465-9921-9-54. Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Petermann, I. et al. Lysosomal,

cytoskeletal and metabolic alterations in cardiomyopathy of cathepsin L knockout mice. FASEB J 20, 1266–1268 (2006). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Tang, Q. et al. Lysosomal

cysteine peptidase cathepsin L protects against cardiac hypertrophy through blocking AKT/GSK3beta signaling. J Mol Med (Berl) 87, 249–260 (2009). Article CAS Google Scholar * Guha, S.

& Padh, H. Cathepsins: fundamental effectors of endolysosomal proteolysis. Indian journal of biochemistry & biophysics 45, 75–90 (2008). CAS Google Scholar * Barascuk, N. et al. A

novel assay for extracellular matrix remodeling associated with liver fibrosis: An enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for a MMP-9 proteolytically revealed neo-epitope of type III

collagen. Clinical biochemistry 43, 899–904 (2010). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Siebuhr, A. S. et al. Matrix metalloproteinase-dependent turnover of cartilage, synovial membrane

and connective tissue is elevated in rats with collagen induced arthritis. Journal of translational medicine 10, 195 (2012), 10.1186/1479-5876-10-195. Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS

Google Scholar * Papasotiriou, M. et al. Serum and urine markers of collagen degradation reflect renal fibrosis in experimental kidney diseases. Nephrology, dialysis, transplantation 30(7),

1112–21 (2015). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Obermajer, N., Jevnikar, Z., Doljak, B. & Kos, J. Role of cysteine cathepsins in matrix degradation and cell signalling.

Connective tissue research 49, 193–196 (2008). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Zhang, G. & Eddy, A. A. Urokinase and its receptors in chronic kidney disease. Front Biosci 13,

5462–5478 (2008). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Han, B., Nakamura, M., Mori, I., Nakamura, Y. & Kakudo, K. Urokinase-type plasminogen activator system and

breast cancer (Review). Oncology reports 14, 105–112 (2005). CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Deryugina, E. I. & Quigley, J. P. Cell surface remodeling by plasmin: a new function for an

old enzyme. Journal of biomedicine & biotechnology 2012, 564259 (2012), 10.1155/2012/564259. Article CAS Google Scholar * Stepanova, V. V. & Tkachuk, V. A. Urokinase as a

multidomain protein and polyfunctional cell regulator. Biochemistry (Mosc) 67, 109–118 (2002). Article CAS Google Scholar * Czekay, R. P., Kuemmel, T. A., Orlando, R. A. & Farquhar,

M. G. Direct binding of occupied urokinase receptor (uPAR) to LDL receptor-related protein is required for endocytosis of uPAR and regulation of cell surface urokinase activity. Mol Biol

Cell 12, 1467–1479 (2001). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Schaefer, L., Han, X., Gretz, N. & Schaefer, R. M. Alterations of cathepsins B, H and L in proximal

tubules from polycystic kidneys of the Han:SPRD rat. Kidney Int 50, 424–431 (1996). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Huang, S. et al. Suppressed activities of cathepsins and

metalloproteinases in the chronic model of puromycin aminonucleoside nephrosis. Kidney Blood Press Res 22, 121–127 (1999). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Peres, G. B., Juliano, M. A.,

Simoes, M. J. & Michelacci, Y. M. Lysosomal enzymes are decreased in the kidney of diabetic rats. Biochim Biophys Acta 1832, 85–95 (2013). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar *

Shechter, P., Boner, G. & Rabkin, R. Tubular cell protein degradation in early diabetic renal hypertrophy. J Am Soc Nephrol 4, 1582–1587 (1994). CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Sever, S.

et al. Proteolytic processing of dynamin by cytoplasmic cathepsin L is a mechanism for proteinuric kidney disease. J Clin Invest 117, 2095–2104 (2007). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central

Google Scholar * Goto, M., Mizunashi, K., Kimura, N. & Furukawa, Y. Decreased sensitivity of distal nephron and collecting duct to parathyroid hormone in pseudohypoparathyroidism type

I. J Am Soc Nephrol 12, 1965–1970 (2001). CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Murata, M. et al. Novel epoxysuccinyl peptides. Selective inhibitors of cathepsin B, _in vitro_. FEBS letters 280,

307–310 (1991). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Koike, M. et al. Cathepsin D deficiency induces lysosomal storage with ceroid lipofuscin in mouse CNS neurons. J Neurosci 20,

6898–6906 (2000). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Steinfeld, R. et al. Cathepsin D deficiency is associated with a human neurodegenerative disorder. Am J Hum Genet

78, 988–998 (2006). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Siintola, E. et al. Cathepsin D deficiency underlies congenital human neuronal ceroid-lipofuscinosis. Brain 129,

1438–1445 (2006). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Zheng, G. & Harris, D. C. Plasmin in renal interstitial fibrosis: innocent or guilty? Kidney Int 66, 455–456 (2004). Article PubMed

Google Scholar * Eddy, A. A. & Fogo, A. B. Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 in chronic kidney disease: evidence and mechanisms of action. J Am Soc Nephrol 17, 2999–3012 (2006).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Hattori, N. et al. The plasminogen activation system reduces fibrosis in the lung by a hepatocyte growth factor-dependent mechanism. Am J Pathol 164,

1091–1098 (2004). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Lieber, A. et al. Adenovirus-mediated urokinase gene transfer induces liver regeneration and allows for efficient

retrovirus transduction of hepatocytes _in vivo_. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 92, 6210–6214 (1995). Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Yamaguchi, I. et al. Endogenous

urokinase lacks antifibrotic activity during progressive renal injury. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 293, F12–19 (2007). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Mackay, A. R., Corbitt, R. H.,

Hartzler, J. L. & Thorgeirsson, U. P. Basement membrane type IV collagen degradation: evidence for the involvement of a proteolytic cascade independent of metalloproteinases. Cancer

research 50, 5997–6001 (1990). CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Law, R. H., Abu-Ssaydeh, D. & Whisstock, J. C. New insights into the structure and function of the plasminogen/plasmin

system. Current opinion in structural biology 23, 836–841 (2013). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Huang, Y., Border, W. A., Lawrence, D. A. & Noble, N. A. Noninhibitory PAI-1

enhances plasmin-mediated matrix degradation both _in vitro_ and in experimental nephritis. Kidney Int 70, 515–522 (2006). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * van Kasteren, S. I. et al.

A multifunctional protease inhibitor to regulate endolysosomal function. ACS chemical biology 6, 1198–1204 (2011). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Racusen, L. C. et

al. Cell lines with extended _in vitro_ growth potential from human renal proximal tubule: characterization, response to inducers and comparison with established cell lines. The Journal of

laboratory and clinical medicine 129, 318–329 (1997). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This work was funded by NIHR Newcastle Biomedical Research

Centre, Northern Counties Kidney Research Fund (NCKRF) and Wellcome Trust Institutional Strategic Support schemes granted to AM and also UK MRC NIRG (G0900535) to FO. This work was also

funded by the cross-council Lifelong Health and Wellbeing initiative which is managed by the MRC (award reference i L016354). The IVIS® Spectrum system was funded by Welcome Trust Equipment

grant 087961. CF and AM salaries are funded through NIHR Newcastle Biomedical Research Centre and Newcastle University NURF’s scheme respectively. PC is funded by University of Naples

Federico II. Ms Lidia Sanchez and Mr Aldi Situmorang technical support and Prof Derek A Mann critical input were highly appreciated. AUTHOR INFORMATION AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Fibrosis

Research Group, Institute of Cellular Medicine, Newcastle University, Newcastle Upon Tyne, UK Christopher Fox, Pasquale Cocchiaro, Fiona Oakley, Rachel Howarth, Krystena Callaghan, Jack

Leslie, Saimir Luli, Neil S. Sheerin & Anna Moles * Department of Molecular Medicine and Medical Biotechnology, University of Naples Federico II, Italy Pasquale Cocchiaro * Department of

Cellular Pathology, Royal Victoria Infirmary, Newcastle Upon Tyne, UK Katrina M. Wood * Nordic Bioscience, Herlev, 2730, Denmark Federica Genovese Authors * Christopher Fox View author

publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Pasquale Cocchiaro View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Fiona

Oakley View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Rachel Howarth View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google

Scholar * Krystena Callaghan View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Jack Leslie View author publications You can also search for this author

inPubMed Google Scholar * Saimir Luli View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Katrina M. Wood View author publications You can also search for

this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Federica Genovese View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Neil S. Sheerin View author publications You

can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Anna Moles View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CONTRIBUTIONS C.F. and A.M.

performed the majority of the experiments with assistance from P.C., F.O., R.H. and K.C. Human CKD sections were provided and histologically assessed by K.M.W. J.L. performed the UUO 5 day’s

surgeries. F.G. performed the sC3M ELISA assay. S.L. assisted with IVIS experiments. N.S.S. contributed to the experimental design and critically reviewed the manuscript. A.M. conceived the

study, planned the experiments and wrote the paper. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS The authors declare no competing financial interests. ELECTRONIC SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this

article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will

need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Reprints and permissions ABOUT

THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Fox, C., Cocchiaro, P., Oakley, F. _et al._ Inhibition of lysosomal protease cathepsin D reduces renal fibrosis in murine chronic kidney disease. _Sci Rep_ 6,

20101 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep20101 Download citation * Received: 14 October 2015 * Accepted: 18 December 2015 * Published: 02 February 2016 * DOI:

https://doi.org/10.1038/srep20101 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not currently

available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative