Play all audios:

ABSTRACT Lipid droplets (LD) play a central role in lipid homeostasis by controlling transient fatty acid (FA) storage and release from triacylglycerols stores, while preventing high levels

of cellular toxic lipids. This crucial function in oxidative tissues is altered in obesity and type 2 diabetes. Perilipin 5 (PLIN5) is a LD protein whose mechanistic and causal link with

lipotoxicity and insulin resistance has raised controversies. We investigated here the physiological role of PLIN5 in skeletal muscle upon various metabolic challenges. We show that PLIN5

protein is elevated in endurance-trained (ET) subjects and correlates with muscle oxidative capacity and whole-body insulin sensitivity. When overexpressed in human skeletal muscle cells to

recapitulate the ET phenotype, PLIN5 diminishes lipolysis and FA oxidation under basal condition, but paradoxically enhances FA oxidation during forskolin- and contraction- mediated

lipolysis. Moreover, PLIN5 partly protects muscle cells against lipid-induced lipotoxicity. In addition, we demonstrate that down-regulation of PLIN5 in skeletal muscle inhibits

insulin-mediated glucose uptake under normal chow feeding condition, while paradoxically improving insulin sensitivity upon high-fat feeding. These data highlight a key role of PLIN5 in LD

function, first by finely adjusting LD FA supply to mitochondrial oxidation, and second acting as a protective factor against lipotoxicity in skeletal muscle. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY

OTHERS SKELETAL MUSCLE-SECRETED DLPC ORCHESTRATES SYSTEMIC ENERGY HOMEOSTASIS BY ENHANCING ADIPOSE BROWNING Article Open access 30 November 2023 LACK OF ADIPOCYTE IP3R1 REDUCES DIET-INDUCED

OBESITY AND GREATLY IMPROVES WHOLE-BODY GLUCOSE HOMEOSTASIS Article Open access 09 March 2023 PERILIPIN 5 LINKS MITOCHONDRIAL UNCOUPLED RESPIRATION IN BROWN FAT TO HEALTHY WHITE FAT

REMODELING AND SYSTEMIC GLUCOSE TOLERANCE Article Open access 03 June 2021 INTRODUCTION Cytosolic lipid droplets (LD) are important energy-storage organelles in most tissues1. LD are

composed of a lipid core, mainly made of triacylglycerols (TAG), surrounded by a phospholipid monolayer in which are embedded proteins2,3. LD are dynamic organelles playing a central role in

fatty acid (FA) trafficking4. Importantly, it has been suggested that altered LD dynamics could contribute to the development of muscle insulin resistance, by facilitating the emergence of

cellular toxic lipids such as diacylglycerols (DAG) and ceramides (CER) known to impair insulin action5,6. LD therefore buffers intracellular FA flux, a function particularly critical in

oxidative tissues such as skeletal muscle with a high lipid turnover and metabolic demand7. Skeletal muscle is also a main site for postprandial glucose disposal, and muscle insulin

resistance is a major risk factor of type 2 diabetes8. The LD surface is coated by perilipins and other structural proteins1. Enzymes involved in lipid metabolism such as lipases and

lipogenic enzymes interact with LD. Perilipin 5 (PLIN5) belongs to the family of perilipins, and is highly expressed in oxidative tissues such as liver, heart, brown adipose tissue and

skeletal muscle9,10. A recent study from Bosma and colleagues has described that overexpressing PLIN5 in mouse skeletal muscle increases intramyocellular TAG (IMTG) content11, which is in

agreement with other studies showing that PLIN5 acts as a lipolytic barrier to protect the LD against the hydrolytic activity of cellular lipases12,13. Interestingly, PLIN5 was also

described to localize to mitochondria14, and suggested to enhance FA utilization15. However, a protective role of PLIN5 against lipid-induced insulin resistance could not be confirmed after

gene electroporation of PLIN5 in rat _tibialis anterior_ muscle11 and muscle-specific PLIN5 overexpression in mice16. In addition, a direct role of PLIN5 in facilitating FA oxidation upon

increased metabolic demand has never been demonstrated in skeletal muscle. To reconcile data from the literature, a hypothetical model would be that PLIN5 exhibits a dual role, buffering

intracellular FA fluxes to prevent lipotoxicity in the resting state on one hand, and facilitating FA oxidation upon increased metabolic demand in the contracting state on the other hand.

The aim of the current work was therefore to investigate the putative dual role of PLIN5 in the regulation of FA metabolism in skeletal muscle. The functional role of PLIN5 was studied _in

vitro_ in human primary muscle cells and _in vivo_ in mouse skeletal muscle. Our data here reveal a key role of PLIN5 to adjust LD FA supply to metabolic demand, and also demonstrate that

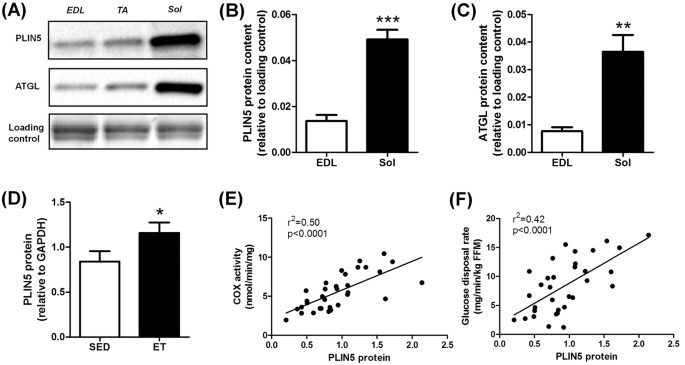

changes in PLIN5 expression influences lipotoxicity and insulin sensitivity in skeletal muscle. RESULTS PLINN5 RELATES TO OXIDATIVE CAPACITY IN MOUSE AND HUMAN SKELETAL MUSCLE Muscle PLIN5

content was measured in various types of skeletal muscles in the mouse (Fig. 1A). We observed that PLIN5 was highly expressed in oxidative _soleus_ muscle compared to mixed _tibialis

anterior_ or to the more glycolytic _extensor digitorum longus_ muscle (3.6 fold, p < 0.001) (Fig. 1B). A similar expression pattern was observed for ATGL protein (4.7 fold, p = 0.0019)

(Fig. 1C). In human _vastus lateralis_ muscle, we observed a higher PLIN5 protein content in lean endurance-trained compared to lean sedentary individuals (+38%, p = 0.033) (Fig. 1D). A

robust relationship between muscle PLIN5 and cytochrome oxidase activity, a marker of muscle oxidative capacity, was observed (r2 = 0.50, p < 0.0001) (Fig. 1E). Significant positive

correlations were also noted with citrate synthase activity (r2 = 0.42, p < 0.0001) and β-hydroxy-acyl-CoA-dehydrogenase (r2 = 0.23, p = 0.0053). Importantly, muscle PLIN5 protein show a

strong positive association with glucose disposal rate measured during euglycemic hyperinsulinemic clamp in subjects with varying degrees of BMI and fitness (r2 = 0.42, p < 0.0001) (Fig.

1F). Collectively, these data show that PLIN5 relates to muscle oxidative capacity and insulin sensitivity in mouse and human skeletal muscle. PLIN5 OVEREXPRESSION REDUCES LIPOLYSIS AND FA

OXIDATION UNDER BASAL CONNDITIONS IN HUMAN PRIMARY MYOTUBES Human skeletal muscle cells differentiated into myotubes are suited to perform mechanistic and metabolic studies11. However, PLIN5

mRNA expression is nearly undetectable in human primary myotubes compared to human muscle tissue (11 Ct difference, 211 = 2054 fold lower expression) (Supplemental Fig. S1). To recapitulate

the ET phenotype _in vitro_ in skeletal muscle cells, we overexpressed PLIN5 to gain further insight into its functional and metabolic role. Adenovirus-mediated PLIN5 overexpression led to

a significant increase of PLIN5 protein content (3.6-fold, p = 0.013) (Fig. 2A). We first examined the effect of PLIN5 overexpression on lipolysis and FA metabolism under basal condition,

using a Pulse-Chase design. Endogenous TAG pool was pre-labeled (i.e. pulsed) overnight using [1-14C] oleate. At the end of the pulse phase (i.e. T0), cells were chased for 3 h in a medium

containing a low glucose concentration to promote lipolysis (i.e. T3). We found that PLIN5 overexpression decreased FA release into the culture medium (−34%, p = 0.044) (Fig. 2B), which was

accompanied by a sharp reduction of FA oxidation compared to control cells (−46%, p = 0.0025) (Fig. 2C). We observed a 56% TAG depletion at T3 (i.e. after 3 hours of chase in a low-glucose

medium) in control cells. PLIN5 overexpressing cells exhibited a lower TAG depletion rate compared to control cells (−38%, p = 0.0022) (Fig. 2D). Since the size of the TAG pool is a major

determinant of TAG breakdown rate17, lipid trafficking rates (FA and DAG) were normalized to TAG content. Consistently, intracellular DAG and FA accumulation during the chase period was

totally abrogated by PLIN5 overexpression (Fig. 2E,F). FA and glucose are the main nutrients competing for fuel oxidation in skeletal muscle18. By slowing down lipid utilization, PLIN5

overexpression enhanced basal glycogen synthesis (+24%, p = 0.045) (Fig. 2G) and glucose oxidation (+74%, p = 0.010) (Fig. 2H). As previously observed in this cell model system19, this

metabolic switch was paralleled by a significant down-regulation of _pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 4_ (PDK4) (−36%, p = 0.024) (Fig. 2I). Taken together, these results clearly show that

PLIN5 overexpression slows down lipolysis and FA oxidation and favors a switch towards glucose metabolism in human muscle cells. PLIN5 OVEREXPRESSION FACILITATES LIPID OXIDATION UPON

INCREASED METABOLIC DEMAND Considering that PLIN5 is elevated in skeletal muscle of athletes with a high lipid turnover, we investigated its role under stimulation of lipolysis, increased

TAG turnover and metabolic demand in human primary myotubes. Thus PLIN5-mediated TAG accumulation (+93%, p = 0.0002) was reduced in the presence of forskolin (a potent lipolysis activator)

(+75%, p = 0.0006) (Fig. 3A). In line with this, FA oxidation was reduced by 60% in PLIN5 overexpressing myotubes under basal conditions (p < 0.0001), while this decrease was of only 35%

upon forskolin stimulation (p = 0.01) (Fig. 3B). Overall, PLIN5 overexpression greatly potentiated forskolin-induced FA oxidation when compared to control cells (+77%, p = 0.007) (Fig. 3C).

Because muscle contraction represents a more physiological stimulation of FA metabolism and increased metabolic demand, we used a model of electrical pulse stimulation (EPS) to recapitulate

contraction-mediated lipolysis _in vitro_. As a model validation, we observed no significant change in total glycogen content and a sharp increase of FA oxidation, which represent classical

skeletal muscle physiological adaptations to endurance training (REF). These effects were accompanied by a robust induction of interleukin-6 gene expression, a well-known exercise-induced

myokine (Supplemental Fig. S2). Interestingly, despite no major change in TAG pools under basal or stimulated conditions (Fig. 3D), we observed a very sharp increase of EPS-mediated FA

oxidation in PLIN5 overexpressing cells (2.4 fold, p = 0.014) (Fig. 3E). Importantly, we observed that EPS increased FA oxidation by 1.7 fold in control myotubes, while this effect was

robustly enhanced up to 12.7 fold in PLIN5 overexpressing cells (Fig. 3F). Together, this suggests for the very first time that PLIN5 is necessary to boost TAG lipolysis and FA oxidation

upon increased metabolic demand in skeletal muscle. PLIN5 EXERT A PROTECTIVE ROLE AGAINST PALMITATE-INDUCED LIPOTOXICITY Besides a key role in controlling LD lipolysis, PLIN5 may sequester

toxic lipids into LD and reduce intracellular lipotoxic insults20. To test this hypothesis, we challenged myotubes with palmitate at a concentration known to induce lipotoxicity and insulin

resistance21. As a model validation, we first observed that palmitate treatment strongly elevated total diacylglycerols (+4.7 fold, p < 0.0001) and ceramides (+4 fold, p < 0.0001)

levels while inhibiting insulin-mediated glycogen synthesis (−37%, p = 0.016) (Fig. 4). Of note, PLIN5 overexpressing myotubes were partly protected from palmitate-mediated insulin

resistance and lipotoxicity. Insulin-stimulated glycogen synthesis was higher in PLIN5 overexpressing myotubes challenged with palmitate compared to control myotubes (+26%, p = 0.0025) (Fig.

4A). Similarly, palmitate-mediated DAG accumulation was slightly reduced in PLIN5 overexpressing myotubes (−16%, p = 0.039) (Fig. 4B). Finally, PLIN5 overexpressing myotubes displayed

reduced concentrations of all ceramides species measured in response to palmitate treatment (Two-way ANOVA p = 0.04), particularly due to reduced ceramide d18:1/16:0 content (Fig. 4C), the

most abundant ceramide species in our cell model. Collectively, these results highlight a slight protective role of PLIN5 against lipotoxicity and palmitate-induced insulin resistance in

muscle cells. PLIN5 KNOCKDOWN IN MOUSE SKELETAL MUSCLE INCREASES LIPID OXIDATION AND REDUCES INSULIN-STIMULATED GLUCOSE UPTAKE UNDER NORMAL CHOW DIET Considering that PLIN5 is strongly

expressed in skeletal muscle and that previous gain-of-function studies in muscle failed to substantiate the causal and mechanistic link between PLIN5 and insulin sensitivity, we assessed

the physiological role of PLIN5 _in vivo_ by inducing a muscle-restricted loss-of-function. We knocked down its expression by injecting an AAV1 containing a shRNA directed against PLIN5 in

_tibialis anterior_ muscle of 10-week old C57BL/6 J mice. Intramuscular AAV1-shRNA-PLIN5 injection significantly reduced PLIN5 mRNA expression (−23%, p = 0.014) (Fig. 5A) and protein content

(−21%, p = 0.024) (Fig. 5B) compared to the contralateral leg injected with an AAV1 containing a non-targeted shRNA. Of note, no functional compensation by other PLIN isoforms was observed

in PLIN5 knocked down muscles (Supplemental Fig. S3). In agreement with _in vitro_ data in the basal state, knockdown of PLIN5 increased the rate of FA oxidation to CO2 (+51%) and ASM (i.e.

acid soluble metabolites) (+21%) (p < 0.05) (Fig. 5C). No change in glucose oxidation was observed (Fig. 5D). Since PLIN5 null mice exhibit signs of insulin resistance in skeletal

muscle22, we next measured insulin-stimulated glucose uptake. Interestingly, PLIN5 knockdown decreased insulin-stimulated muscle glucose uptake (−27%, p = 0.0003) (Fig. 5E). However, muscle

insulin resistance appeared independent of significant change in total (shNT 0.11 ± 0.01 _vs._ shPLIN5 0.12 ± 0.02 nmol/mg, NS) and various ceramide species. Taken together, our data argue

for a physiological role of PLIN5 in the regulation of FA oxidation and insulin sensitivity in skeletal muscle _in vivo_. PLIN5 KNOCKDOWN IN MOUSE SKELETAL MUSCLE AMELIORATES INSULIN ACTION

UNDER HIGH-FAT FEEDING We next investigated the impact of PLIN5 knockdown in _tibialis anterior_ muscle under high fat diet feeding for 12 weeks. Intramuscular AAV1-shRNA-PLIN5 injection in

HFD-fed mice reduced PLIN5 mRNA level by 31% (p = 0.015) (Fig. 6A) and protein content by 54% (p = 0.0003) (Fig. 6B), without any compensatory changes in the expression level of PLIN2, PLIN3

and PLIN4 (Supplemental Fig. S3). In contrast with normal chow diet-fed mice, insulin-stimulated muscle glucose uptake was improved in PLIN5 knocked down legs of HFD-fed mice (+37%, p =

0.0031) (Fig. 6C). This was accompanied by a decrease in total ceramide content (−18%, p = 0.028) (Fig. 6D), while DAG content remained unchanged (Fig. 6E). In agreement, we also observed a

significant increase of insulin-stimulated Akt phosphorylation on serine 473 and threonine 308 in PLIN5 knockdown muscle compared to the contralateral leg (1.7 fold and 2.1 fold,

respectively, p = 0.048) (Fig. 6F). Collectively, while PLIN5 knockdown promotes insulin resistance in skeletal muscle of chow-fed mice, it paradoxically partly protects skeletal muscle

against HFD-induced insulin resistance. HIGH-FAT FEEDING UP-REGULATES PLIN5 IN SKELETAL MUSCLE INDEPENDENTLY OF PPARΒ PLIN5 has been described as a _Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated

Receptors_ (PPAR)-target gene in a mouse muscle cell line model23. Since we noted a striking up-regulation of PLIN5 with high-fat feeding at both mRNA and protein levels (Supplemental Fig.

S4), we examined PLIN5 regulation by PPAR _in vitro_ and _in vivo_. We confirmed previous findings23 showing that PLIN5 is a PPARβ-responsive gene in human primary myotubes (Supplemental

Fig. S4). Interestingly, PLIN5 was specifically induced by a PPARβ agonist (GW0742) in this cell model system (5.3 fold, p < 0.001). We next investigated whether HFD-mediated

up-regulation of PLIN5 was mediated by activation of PPARβ in skeletal muscle _in vivo_. Of interest, muscle PLIN5 protein content was similar in PPARβ knockout mice, while HFD-mediated

up-regulation of PLIN5 was unaffected in PPARβ knockout mice (Supplemental Fig. S4). Thus, HFD-mediated up-regulation of PLIN5 could be seen as an adaptive response to facilitate fat storage

into LD of excess incoming FA and minimize lipotoxicity. Although PLIN5 is a PPARβ-responsive gene in skeletal muscle, HFD-mediated up-regulation of PLIN5 appears independent of PPARβ.

DISCUSSION LD play a critical role in oxidative tissues to maintain appropriate fuel supply during periods of energy needs but also to buffer daily fluxes of FA to avoid cellular

lipotoxicity. PLIN5 has been previously shown as a LD protein inhibiting lipolysis and correlating with insulin sensitivity13,24,25. The current work demonstrates for the first time that

PLIN5 protects against palmitate-induced insulin resistance and facilitates FA oxidation in response to muscle contraction and increased metabolic demand _in vitro_. We further show a causal

link between down-regulation of PLIN5 and insulin resistance _in vivo_ in mouse skeletal muscle. We show here that the skeletal muscle enriched PLIN5 protein has a key role in controlling

fat oxidation and lipotoxicity by fine tuning FA fluxes in and out of the LD from the resting to the contracting state. PLIN5 facilitates fat storage into LD and inhibits FA oxidation in the

resting state while sharply boosting IMTG lipolysis and FA oxidation during muscle contraction or PKA stimulation (Fig. 7). Although the precise molecular mechanism was not investigated

here, one can speculate that PLIN5 is physically relocated out of the LD to favor LD hydrolysis by adipose triglyceride lipase and FA channeling into mitochondria15. We first observed that

PLIN5 tightly correlates with oxidative capacity of mouse and human skeletal muscle. Muscle PLIN5 content strongly correlated as well with whole-body insulin sensitivity. In addition, we

confirm that endurance-trained subjects exhibited higher levels of PLIN5 protein compared to lean sedentary subjects as previously described24. This is in line with various studies showing

that aerobic exercise training increases PLIN5 protein, oxidative capacity and insulin sensitivity in skeletal muscle26,27,28. Thus endurance-trained individuals display higher lipid

content, oxidative capacity and insulin sensitivity compared to matched sedentary controls29,30. We next observed that PLIN5 overexpression in human primary myotubes has a modest protective

effect against saturated fat-induced lipotoxicity and insulin-resistance. Thus PLIN5 seems to preserve insulin action (glycogen synthesis) by sequestering toxic saturated lipids into

LDs31,32. Our data are in agreement with a recent study showing that PLIN5 overexpression in C2C12 mouse myotubes facilitate palmitate sequestration into LD and remodels their lipid

composition20. Finally, a recent study by Mason and colleagues reported that PLIN5 knockout mice develop insulin resistance associated with ceramide accumulation in skeletal muscle22.

Studies from different groups have shown that PLIN5 overexpression increases TAG storage in mouse skeletal11 and cardiac12 muscle. We observed here that PLIN5 overexpression slows down

TAG-derived lipolysis and FA oxidation in basal resting conditions, and concomitantly induces a switch towards glucose utilization. Of importance, two reports described that PLIN5 not only

localizes to the LD surface, but also to the mitochondria14,15. We show here for the first time that PLIN5 overexpression in human primary myotubes sharply enhanced FA oxidation upon

forskolin- and contraction-induced lipolysis activation and metabolic demand. This suggests that PLIN5 might provide a physical linkage between LD and mitochondria in a context of increased

energy demand. Our data are in agreement with data in ALM12 liver cells in which PLIN5 overexpression enhanced FA release when lipolysis was activated by the adenylyl cyclase activator

forskolin15. PLIN5 appears to be phosphorylated by PKA (cAMP-dependent protein kinase)33, in a similar fashion as PLIN1 in adipose tissue34. The molecular pathways induced by contraction

converging to PLIN5 where not investigated here and require a detailed examination in future studies. We next investigated the physiological role of PLIN5 in skeletal muscle _in vivo_

through loss-of-function studies using AAV gene delivery. PLIN5 was knocked down in one leg of mice fed either standard chow or high fat diets. In line with our _in vitro_ data, PLIN5

knockdown induced a compensatory increase of FA oxidation rate under standard chow diet. This could be explained by a better access of lipases to LD and greater TAG turnover as shown in

cardiac muscle of PLIN5-deficient mice35. Interestingly, it has been described that a global PLIN5 deficiency induces muscle insulin resistance22. However, this effect may be confounded by

systemic factors. In line with the positive association between muscle PLIN5 content and insulin sensitivity observed in humans, we show that a partial down-regulation of PLIN5 in mouse

skeletal muscle inhibits insulin-stimulated glucose uptake. This highlights for the first time that down-regulation of PLIN5 promotes insulin resistance in a muscle-autonomous fashion. This

might be explained by a deficient coupling between FA supply and mitochondrial oxidation resulting in muscle inflammation, although further work is needed to better understand these

mechanisms. Under HFD, we first observed a striking up-regulation of PLIN5 mRNA and protein levels in skeletal muscle. We describe here PLIN5 as a PPARβ target gene in human primary skeletal

muscle cells, which is in agreement with data from C2C12 mouse myotubes23. However, we show for the first time that baseline expression of muscle PLIN5 is not influenced by PPARβ, and that

HFD-mediated up-regulation of PLIN5 is not driven by PPARβ. Although baseline expression of muscle PLIN5 is strongly reduced in PPARα knockout mice, HFD-mediated up-regulation of PLIN5 is

not prevented as well in these transgenic mice23. It is still unclear how HFD promotes the up-regulation of muscle PLIN5 but this may be under the control of PPARγ which contribute to lipid

accumulation in skeletal muscle during high fat feeding36. Other transcription factors related to lipid storage may be involved. Thus, HFD-mediated up-regulation of PLIN5 seems to be an

adaptive mechanism to favor FA sequestering and accumulation into TAG pools. However, and contrary to our expectations, muscle PLIN5 knockdown in a context of high fat diet improved muscle

insulin sensitivity. It has been previously shown that high fat feeding is accompanied by an upregulation of muscle oxidative capacity which does not appear sufficient to prevent both TAG

accumulation and lipotoxicity37,38. Thus, lower levels of PLIN5 during HFD, achieved by AAV-mediated knockdown, might in this context facilitate IMTG lipolysis and FA utilization in a

resting muscle with high lipid content, and therefore reduce lipotoxicity. This hypothesis is partly supported by the observation of a reduced total ceramide content and an increase of Akt

Ser473 and Thr308 phosphorylation, while no change in total DAG was observed in PLIN5-knocked down muscle of HFD-fed mice. These data are consistent with at least another study showing that

PLIN5 knockout mice display a markedly improved glucose tolerance under HFD with a trend toward increased peripheral glucose clearance22. Thus our data brings light on this previous

observation showing an elevated rate of glucose uptake in PLIN5-deficient skeletal muscles. Overall, although PLIN5 exhibits a protective role against lipotoxicity in standard nutritional

conditions, HFD-mediated up-regulation of PLIN5 appears deleterious for the maintenance of insulin action in skeletal muscle. In summary, we provide mechanistic evidences that PLIN5 plays a

key role in skeletal muscle. We show for the first time a dual role of PLIN5, favoring TAG accumulation and protecting from high intracellular toxic lipid levels in the resting state, while

facilitating IMTG lipolysis and FA oxidation during contraction and increased metabolic demand. This work further highlights the important role of LD function and dynamics for metabolic

regulation and for the maintenance of insulin sensitivity in skeletal muscle. METHODS HUMAN MUSCLE SAMPLING Data and samples from men aged between 34 and 53 years with varying degree of BMI

and insulin sensitivity were available from a prior study (n = 33)39. Of these, 11 were normal weight sedentary controls, 11 were obese sedentary and 11 were normal weight endurance-trained

individuals. The overall study design and subject testing have been partly described in39. The study was performed according to the latest version of the Declaration of Helsinki and the

Current International Conference on Harmonization (ICH) guidelines. The research protocol was approved by the Université Laval ethics committee and all subjects provided written informed

consent. Samples of _vastus lateralis_ (~40 mg) were obtained, blotted free of blood, cleaned to remove fat and connective tissue and snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen for Western blot

analyses. All samples were stored at −80 °C under argon or nitrogen gas until use. SKELETAL MUSCLE PRIMARY CELL CULTURE Satellite cells from _rectus abdominis_ of healthy male subjects (age

34.3 ± 2.5 years, BMI 26.0 ± 1.4 kg/m2, fasting glucose 5.0 ± 0.2 mM) were kindly provided by Prof. Arild C. Rustan (Oslo University, Norway). Satellite cells were isolated by trypsin

digestion, preplated on an uncoated petri dish for 1 h to remove fibroblasts, and subsequently transferred to T-25 collagen-coated flasks in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) low

glucose (1 g/L) supplemented with 10% FBS and various factors (human epidermal growth factor, BSA, dexamethasone, gentamycin, fungizone, fetuin) as previously described40. Cells from several

donors were pooled and grown at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. Differentiation of myoblasts (i.e. activated satellite cells) into myotubes was initiated at ∼80–90% confluence,

by switching to α-Minimum Essential Medium with 2% penicillin-streptomycin, 2% FBS, and fetuin (0.5 mg/ml). The medium was changed every other day and cells were grown up to 5 days. For

pharmacological treatments, cells were exposed to a PPARα or PPARβ agonist (GW7647 and GW0742, respectively) or a PPARβ antagonist (GSK0660) for 24 h at the end of the differentiation.

OVEREXPRESSION OF PLIN5 IN HUMAN MYOTUBES For overexpression experiments, adenoviruses expressing in tandem GFP and human PLIN5 (hPLIN5) were used (Vector Biolabs, Philadelphia, PA). Control

was performed using adenoviruses containing GFP gene only. Myotubes were infected with both adenoviruses at day 4 of differentiation and remained exposed to the virus for 24 h in serum-free

DMEM containing 100 μM of oleate complexed to BSA (ratio 2/1). Oleate was preferred to palmitate for lipid loading of the cells, to favor triacylglycerol (TAG) synthesis and to avoid the

intrinsic lipotoxic effect of palmitate41. As a model of lipid-induced lipotoxicity and insulin resistance, oleate was replaced by palmitate in some experiments to metabolically challenge

the cells. ANIMAL STUDIES All experimental procedures were approved by a local ethics committee (CEEA122 INSERM US006/CREFRE, protocol n°C14/U1048/DL/13) and performed according to INSERM

animal care facility guidelines and to the 2010/63/UE European Directive for the care and use of laboratory animals. Sixteen week-old male PPARβ knockout and wild-type mice on a SV129/C57Bl6

background were used for muscle tissue collection. Four-week-old C57BL/6 J male mice were housed in a pathogen-free barrier facility (12 h light/dark cycle) and fed either normal chow diet

(10% calories from fat) (D12450J, Research Diets, New Jersey) or high-fat diet (60% calories from fat) (D12492, Research Diets, New Jersey). To induce an _in vivo_ knockdown of PLIN5

specifically in skeletal muscle, mice were injected with 1 × 1011 GC (i.e. genome copy) of AAV1 vector (Vector Biolabs, Philadelphia, PA) in _tibialis anterior_ muscles at 10 weeks of age.

Each mouse had one leg injected with AAV1-shPLIN5 and the contralateral leg injected with AAV1-shNT (nontarget) as a control. Six weeks following the injections, mice were killed by cervical

dislocation and muscles (i.e. _tibialis anterior_ and _extensor digitorum longus_) were dissected and either used _ex-vivo_ for palmitate and glucose oxidation assays or stored at −80 °C

for protein, RNA and lipid analyses. REAL-TIME RT-QPCR Total RNA from cultured myotubes or _tibialis anterior_ muscle was isolated using Qiagen RNeasy mini kit according to manufacturer’s

instructions (Qiagen GmbH, Hilden, Germany). The quantity of RNA was determined on a Nanodrop ND-1000 (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA). Reverse-transcriptase PCR was performed on a

Techne PCR System TC-412 using the Multiscribe Reverse Transcriptase method (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) was performed to determine cDNA content.

All primers were bought from Applied Biosystems and were: 18 S (Taqman assay ID: Hs99999901_s1), PLIN5 (Hs00965990_m1 and Mm00508852_m1), and PDK4 (Hs01037712_m1). The amplification reaction

was performed in duplicate on 10ng of cDNA in 96-well reaction plates on a StepOnePlusTM system (Applied Biosystems). All expression data were normalized by the 2(ΔCt) method using 18 S as

internal control. WESTERN BLOT ANALYSIS Muscle tissues and cell extracts were homogenized in a buffer containing 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 2 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, 30 mM NaPPO4, 10 mM NaF, 1%

Triton X-100, 1.5 mg/ml benzamidine HCl and 10 μl/ml of each: protease inhibitor, phosphatase I inhibitor and phosphatase II inhibitor (Sigma-Aldrich). Tissue homogenates were centrifuged

for 25 min at 15,000 _g_ and supernatants were stored at −80 °C. A total of 30 μg of solubilized proteins from muscle tissue and myotubes were run on a 4–12% SDS-PAGE (Biorad), transferred

onto nitrocellulose membrane (Hybond ECL, Amersham Biosciences), and blotted with the following primary antibodies: PLIN5 (#GP31, Progen), ATGL (#2138, Cell Signaling Technology Inc.), Akt

(#4691, Cell Signaling Technology Inc.), pAkt S473 (#4060, Cell Signaling Technology Inc.), pAkt T308 (#2965, Cell Signaling Technology Inc.). Subsequently, immunoreactive proteins were

blotted with secondary HRP-coupled antibodies (Cell Signaling Technology Inc.) and revealed by enhanced chemiluminescence reagent (SuperSignal West Femto, Thermo Scientific), visualized

using the ChemiDoc MP Imaging System and data analyzed using the ImageLab 4.2 version software (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, USA). GAPDH (#2118, Cell Signaling Technology Inc.) was used

as an internal control. DETERMINATION OF GLUCOSE METABOLISM Cells were pre-incubated with a glucose- and serum-free medium for 90 min, then exposed to DMEM supplemented with D[U-14C] glucose

(1 μCi/ml; PerkinElmer, Boston, MA). Following incubation, glucose oxidation was determined by counting of 14CO2 released into the culture medium. The cells were then solubilized in KOH 30%

and glycogen synthesis was determined as previously described42. Total glycogen content was determined spectrophotometrically after complete hydrolysis into glucose by the

α-amiloglucosidase as previously described43. DETERMINATION OF FATTY ACID METABOLISM Cells were pulsed overnight for 18 h with [1-14C] oleate (1 μCi/ml; PerkinElmer, Boston, MA) and cold

oleate (100 μM) to prelabel the endogenous TAG pool. Oleate was coupled to FA-free BSA in a molar ratio of 5:1. Following the pulse, myotubes were chased for 3 h in DMEM containing 0.1 mM

glucose, 0.5% FA-free BSA, and 10 μM triacsin C to block FA recycling into the TAG pool as described elsewhere44, in absence or presence of 10 μM forskolin to stimulate lipolysis. For

electrical pulse stimulation experiments, cells were chased for 24 h in DMEM containing 1 mM glucose, 0.5% FA-free BSA and 10 μM triacsin C while electrically stimulated by 2 ms pulses at a

frequency of 0.1 Hz. TAG-derived FA oxidation was measured by the sum of 14CO2 and 14C-ASM (acid soluble metabolites) in absence of triacsin C as previously described40. Myotubes were

harvested in 0.2 ml SDS 0.1% at the end of the pulse and of the chase period to determine oleate incorporation into TAG and protein content. The lipid extract was separated by TLC using

heptane-isopropylether-acetic acid (60:40:4, v/v/v) as developing solvent. All assays were performed in duplicates, and data were normalized to cell protein content. Palmitate oxidation rate

was measured as previously described43. TISSUE-SPECIFIC [2-3H] DEOXYGLUCOSE UPTAKE _IN VIVO_ Muscle-specific glucose uptake was assessed in response to an intraperitoneal bolus injection of

2-[1,2-3H(N)]deoxy-D-Glucose (PerkinElmer, Boston, Massachusetts) (0.4μCi/g body weight) and insulin (3 mU/g body weight). The dose of insulin was determined in preliminary studies to reach

a nearly maximal stimulation of insulin signaling and glucose uptake in all muscle types and metabolic tissues. Mice were killed 30 min after injection and tissues were extracted by

precipitation of 2-deoxyglucose-6-phosphate as previously described45. DETERMINATION OF NEUTRAL LIPID AND CERAMIDE CONTENT Triacylglycerols and diacylglycerols were determined by gas

chromatography, and ceramide and sphingomyelin species by high-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry after total lipid extraction as described elsewhere45,46.

STATISTICAL ANALYSES All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 5.0 for Windows (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA). Normal distribution and homogeneity of variance of

the data were tested using Shapiro-Wilk and F tests, respectively. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc tests and Student’s _t_-tests were performed to determine differences between

treatments. Two-way ANOVA and Bonferroni’s post hoc tests were used when appropriate. All values in figures and tables are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was set at _p_

< 0.05. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION HOW TO CITE THIS ARTICLE: Laurens, C. _et al_. Perilipin 5 fine-tunes lipid oxidation to metabolic demand and protects against lipotoxicity in skeletal

muscle. _Sci. Rep._ 6, 38310; doi: 10.1038/srep38310 (2016). PUBLISHER'S NOTE: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional

affiliations. REFERENCES * Fujimoto, T. & Parton, R. G. Not just fat: the structure and function of the lipid droplet. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology 3 (2011). * Olofsson, S.

O. et al. Lipid droplets as dynamic organelles connecting storage and efflux of lipids. Biochimica et biophysica acta 1791, 448–458 (2009). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Fujimoto,

T. & Ohsaki, Y. Cytoplasmic lipid droplets: rediscovery of an old structure as a unique platform. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1086, 104–115 (2006). Article ADS CAS

PubMed Google Scholar * Gao, Q. & Goodman, J. M. The lipid droplet-a well-connected organelle. Frontiers in cell and developmental biology 3, 49 (2015). Article ADS PubMed PubMed

Central Google Scholar * Badin, P. M. et al. Altered skeletal muscle lipase expression and activity contribute to insulin resistance in humans. Diabetes 60, 1734–1742 (2011). Article CAS

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Samuel, V. T. & Shulman, G. I. Mechanisms for insulin resistance: common threads and missing links. Cell 148, 852–871 (2012). Article CAS

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * van Loon, L. J. & Goodpaster, B. H. Increased intramuscular lipid storage in the insulin-resistant and endurance-trained state. Pflugers Arch

451, 606–616 (2006). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * DeFronzo, R. A. & Tripathy, D. Skeletal muscle insulin resistance is the primary defect in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes care 32

Suppl 2, S157–163 (2009). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Wolins, N. E. et al. OXPAT/PAT-1 is a PPAR-induced lipid droplet protein that promotes fatty acid

utilization. Diabetes 55, 3418–3428 (2006). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Dalen, K. T. et al. LSDP5 is a PAT protein specifically expressed in fatty acid oxidizing tissues.

Biochimica et biophysica acta 1771, 210–227 (2007). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Bosma, M. et al. Overexpression of PLIN5 in skeletal muscle promotes oxidative gene expression and

intramyocellular lipid content without compromising insulin sensitivity. Biochimica et biophysica acta 1831, 844–852 (2013). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Pollak, N. M. et al.

Cardiac-specific overexpression of perilipin 5 provokes severe cardiac steatosis via the formation of a lipolytic barrier. Journal of lipid research 54, 1092–1102 (2013). Article CAS

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Wang, C. et al. Perilipin 5 improves hepatic lipotoxicity by inhibiting lipolysis. Hepatology 61, 870–882 (2015). Article CAS PubMed Google

Scholar * Bosma, M. et al. The lipid droplet coat protein perilipin 5 also localizes to muscle mitochondria. Histochemistry and cell biology 137, 205–216 (2012). Article CAS PubMed

Google Scholar * Wang, H. et al. Perilipin 5, a lipid droplet-associated protein, provides physical and metabolic linkage to mitochondria. Journal of lipid research 52, 2159–2168 (2011).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Harris, L. A. et al. Perilipin 5-Driven Lipid Droplet Accumulation in Skeletal Muscle Stimulates the Expression of Fibroblast Growth

Factor 21. Diabetes 64, 2757–2768 (2015). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Kase, E. T. et al. Primary defects in lipolysis and insulin action in skeletal muscle cells

from type 2 diabetic individuals. Biochimica et biophysica acta 1851, 1194–1201 (2015). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Randle, P. J., Garland, P. B., Hales, C. N. & Newsholme,

E. A. The glucose fatty-acid cycle. Its role in insulin sensitivity and the metabolic disturbances of diabetes mellitus. Lancet 1, 785–789 (1963). CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Badin, P. M.

et al. Regulation of skeletal muscle lipolysis and oxidative metabolism by the co-lipase CGI-58. Journal of lipid research 53, 839–848 (2012). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google

Scholar * Billecke, N. et al. Perilipin 5 mediated lipid droplet remodelling revealed by coherent Raman imaging. Integrative biology: quantitative biosciences from nano to macro 7, 467–476

(2015). Article CAS Google Scholar * Pickersgill, L., Litherland, G. J., Greenberg, A. S., Walker, M. & Yeaman, S. J. Key role for ceramides in mediating insulin resistance in human

muscle cells. The Journal of biological chemistry 282, 12583–12589 (2007). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Mason, R. R. et al. PLIN5 deletion remodels intracellular lipid composition

and causes insulin resistance in muscle. Molecular metabolism 3, 652–663 (2014). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Bindesboll, C., Berg, O., Arntsen, B., Nebb, H. I.

& Dalen, K. T. Fatty acids regulate perilipin5 in muscle by activating PPARdelta. Journal of lipid research 54, 1949–1963 (2013). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar *

Amati, F. et al. Skeletal muscle triglycerides, diacylglycerols, and ceramides in insulin resistance: another paradox in endurance-trained athletes? Diabetes 60, 2588–2597 (2011). Article

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Granneman, J. G., Moore, H. P., Mottillo, E. P., Zhu, Z. & Zhou, L. Interactions of perilipin-5 (Plin5) with adipose triglyceride lipase.

The Journal of biological chemistry 286, 5126–5135 (2011). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Goodpaster, B. H., He, J., Watkins, S. & Kelley, D. E. Skeletal muscle lipid content

and insulin resistance: evidence for a paradox in endurance-trained athletes. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism 86, 5755–5761 (2001). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

* Louche, K. et al. Endurance exercise training up-regulates lipolytic proteins and reduces triglyceride content in skeletal muscle of obese subjects. The Journal of clinical endocrinology

and metabolism 98, 4863–4871 (2013). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Shepherd, S. O. et al. Sprint interval and traditional endurance training increase net intramuscular

triglyceride breakdown and expression of perilipin 2 and 5. The Journal of physiology 591, 657–675 (2013). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Henriksson, J. Effect of training and

nutrition on the development of skeletal muscle. Journal of sports sciences 13 SPEC NO, S25–30 (1995). * Henriksson, J. Muscle fuel selection: effect of exercise and training. Proc Nutr Soc

54, 125–138 (1995). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Hunnicutt, J. W., Hardy, R. W., Williford, J. & McDonald, J. M. Saturated fatty acid-induced insulin resistance in rat

adipocytes. Diabetes 43, 540–545 (1994). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Storlien, L. H. et al. Influence of dietary fat composition on development of insulin resistance in rats.

Relationship to muscle triglyceride and omega-3 fatty acids in muscle phospholipid. Diabetes 40, 280–289 (1991). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Pollak, N. M. et al. The interplay of

protein kinase A and perilipin 5 regulates cardiac lipolysis. The Journal of biological chemistry 290, 1295–1306 (2015). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Sanders, M. A. et al.

Endogenous and Synthetic ABHD5 Ligands Regulate ABHD5-Perilipin Interactions and Lipolysis in Fat and Muscle. Cell metabolism 22, 851–860 (2015). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google

Scholar * Kuramoto, K. et al. Perilipin 5, a lipid droplet-binding protein, protects heart from oxidative burden by sequestering fatty acid from excessive oxidation. The Journal of

biological chemistry 287, 23852–23863 (2012). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Chabowski, A., Zendzian-Piotrowska, M., Nawrocki, A. & Gorski, J. Not only

accumulation, but also saturation status of intramuscular lipids is significantly affected by PPARgamma activation. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 205, 145–158 (2012). Article CAS Google Scholar *

Hancock, C. R. et al. High-fat diets cause insulin resistance despite an increase in muscle mitochondria. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 105,

7815–7820 (2008). Article ADS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Oakes, N. D., Kjellstedt, A., Thalen, P., Ljung, B. & Turner, N. Roles of Fatty Acid oversupply and impaired

oxidation in lipid accumulation in tissues of obese rats. J Lipids 2013, 420754 (2013). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Riou, M. E. et al. Predictors of

cardiovascular fitness in sedentary men. Applied physiology, nutrition, and metabolism = Physiologie appliquee, nutrition et metabolisme 34, 99–106 (2009). Article PubMed Google Scholar *

Ukropcova, B. et al. Dynamic changes in fat oxidation in human primary myocytes mirror metabolic characteristics of the donor. The Journal of clinical investigation 115, 1934–1941 (2005).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Bakke, S. S. et al. Palmitic acid follows a different metabolic pathway than oleic acid in human skeletal muscle cells; lower

lipolysis rate despite an increased level of adipose triglyceride lipase. Biochimica et biophysica acta 1821, 1323–1333 (2012). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Laurens, C. et al.

Adipogenic progenitors from obese human skeletal muscle give rise to functional white adipocytes that contribute to insulin resistance. International journal of obesity 40, 497–506 (2016).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Bourlier, V. et al. Enhanced glucose metabolism is preserved in cultured primary myotubes from obese donors in response to exercise training. The

Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism 98, 3739–3747 (2013). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Igal, R. A. & Coleman, R. A. Acylglycerol recycling from triacylglycerol to

phospholipid, not lipase activity, is defective in neutral lipid storage disease fibroblasts. The Journal of biological chemistry 271, 16644–16651 (1996). Article CAS PubMed Google

Scholar * Badin, P. M. et al. High-fat diet-mediated lipotoxicity and insulin resistance is related to impaired lipase expression in mouse skeletal muscle. Endocrinology 154, 1444–1453

(2013). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Coue, M. et al. Defective Natriuretic Peptide Receptor Signaling in Skeletal Muscle Links Obesity to Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes 64, 4033–4045

(2015). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The authors thank Justine Bertrand-Michel, Fabien Riols and Aurélie Batut (Lipidomic Core Facility, INSERM,

UMR 1048 [part of Toulouse Metatoul Platform] for lipidomic analysis, advice and technical assistance. We also thank Cédric Baudelin and Xavier Sudre from the Animal Care Facility. Special

thanks for all the participants for their time and invaluable cooperation. The authors would also like to thank Josée St-Onge, Marie-Eve Riou, Etienne Pigeon, Erick Couillard, Guy Fournier,

Jean Doré, Marc Brunet, Linda Drolet, Nancy Parent, Marie Tremblay, Rollande Couture, Valérie-Eve Julien, Rachelle Duchesne and Ginette Lapierre for their expert technical assistance in the

LIME study. This work was supported by grants from the National Research Agency ANR-12-JSV1-0010-01 (CM), Société Francophone du Diabète (CM), Canadian Institutes of Health Research grant

CIHR MOP-68846 (DRJ) and a Pfizer/CIHR research Chair on the pathogenesis of insulin resistance and cardiovascular diseases (AM). DL is a member of Institut Universitaire de France. AUTHOR

INFORMATION Author notes * Joanisse Denis R. and Moro Cedric contributed equally to this work. AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * INSERM, UMR1048, Institute of Metabolic and Cardiovascular Diseases,

Toulouse, France Claire Laurens, Virginie Bourlier, Aline Mairal, Katie Louche, Pierre-Marie Badin, Etienne Mouisel, Dominique Langin & Cedric Moro * University of Toulouse, Paul

Sabatier University, France Claire Laurens, Virginie Bourlier, Aline Mairal, Katie Louche, Pierre-Marie Badin, Etienne Mouisel, Alexandra Montagner, Hervé Guillou, Dominique Langin &

Cedric Moro * INRA, UMR 1331, TOXALIM, Toulouse, France Alexandra Montagner & Hervé Guillou * Department of Medicine, Laval University, Quebec City, Canada André Marette * Centre de

Recherche de l’Institut Universitaire de Cardiologie et de Pneumologie de Québec, Laval University, Quebec City, Canada André Marette, Angelo Tremblay & Denis R. Joanisse * Department of

Kinesiology, Laval University, Quebec City, Canada Angelo Tremblay & Denis R. Joanisse * CHU-CHUQ, Laval University, Quebec City, Canada John S. Weisnagel * Department of Clinical

Biochemistry, Toulouse University Hospitals, Toulouse, France Dominique Langin Authors * Claire Laurens View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar *

Virginie Bourlier View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Aline Mairal View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed

Google Scholar * Katie Louche View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Pierre-Marie Badin View author publications You can also search for this

author inPubMed Google Scholar * Etienne Mouisel View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Alexandra Montagner View author publications You can

also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * André Marette View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Angelo Tremblay View author

publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * John S. Weisnagel View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Hervé

Guillou View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Dominique Langin View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google

Scholar * Denis R. Joanisse View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Cedric Moro View author publications You can also search for this author

inPubMed Google Scholar CONTRIBUTIONS C.L., V.B., A.M., K.L., P.M.B., E.M., A.M., A.M., A.T., S.J.W., H.G., D.L., D.R.J. and C.M. researched data and edited the manuscript. C.L. and C.M.

wrote the manuscript. Dr. Cedric Moro is the guarantor of this work and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the

accuracy of the data analysis. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS The authors declare no competing financial interests. ELECTRONIC SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL SUPPLEMENTAL DATA RIGHTS AND

PERMISSIONS This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s

Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the

license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE

Laurens, C., Bourlier, V., Mairal, A. _et al._ Perilipin 5 fine-tunes lipid oxidation to metabolic demand and protects against lipotoxicity in skeletal muscle. _Sci Rep_ 6, 38310 (2016).

https://doi.org/10.1038/srep38310 Download citation * Received: 07 September 2016 * Accepted: 07 November 2016 * Published: 06 December 2016 * DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep38310 SHARE

THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Copy to

clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative