Play all audios:

ABSTRACT Cellular actin dynamics is an essential element of numerous cellular processes, such as cell motility, cell division and endocytosis. Actin’s involvement in these processes is

mediated by many actin-binding proteins, among which the cofilin family plays unique and essential role in accelerating actin treadmilling in filamentous actin (F-actin) in a

nucleotide-state dependent manner. Cofilin preferentially interacts with older filaments by recognizing time-dependent changes in F-actin structure associated with the hydrolysis of ATP and

release of inorganic phosphate (Pi) from the nucleotide cleft of actin. The structure of cofilin on F-actin and the details of the intermolecular interface remain poorly understood at atomic

resolution. Here we report atomic-level characterization by magic angle spinning (MAS) NMR of the muscle isoform of human cofilin 2 (CFL2) bound to F-actin. We demonstrate that resonance

assignments for the majority of atoms are readily accomplished and we derive the intermolecular interface between CFL2 and F-actin. The MAS NMR approach reported here establishes the

foundation for atomic-resolution characterization of a broad range of actin-associated proteins bound to F-actin. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS MAGIC ANGLE SPINNING NMR STRUCTURE OF

HUMAN COFILIN-2 ASSEMBLED ON ACTIN FILAMENTS REVEALS ISOFORM-SPECIFIC CONFORMATION AND BINDING MODE Article Open access 19 April 2022 STRUCTURAL BASIS OF ACTIN FILAMENT ASSEMBLY AND AGING

Article Open access 26 October 2022 ANALYSIS TOOLS FOR SINGLE-MONOMER MEASUREMENTS OF SELF-ASSEMBLY PROCESSES Article Open access 18 March 2022 INTRODUCTION Actin is one of the most abundant

proteins in eukaryotic cells and is essential for numerous cellular functions, such as cellular division, cell motility, cell shape changes and mechanical support1. In these processes,

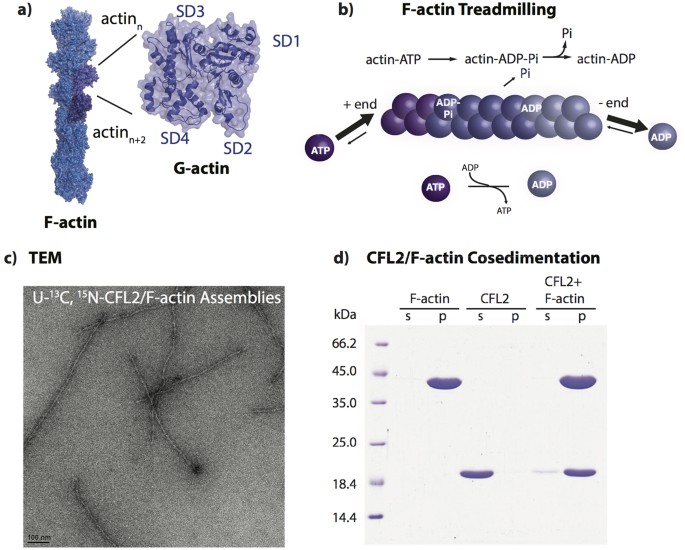

actin functions in a tightly controlled equilibrium between G- (globular) and F- (filamentous) states (Fig. 1a). ATP bound to G-actin is hydrolyzed upon polymerization in a time-dependent

manner so that the younger part of the filament contains subunits in the ATP- and ADP-Pi-states, while the older part is enriched in the ADP-bound subunits (Fig. 1b). This “nucleotide clock”

is recognized and amplified by actin-binding proteins (ABPs), among which ADF/cofilins are essential modulators and coordinators of actin dynamics2. There are three non-redundant isoforms

of human cofilins, namely actin depolymerizing factor (ADF), cofilin 1 (CFL1), and cofilin 2 (CFL2), which differ in tissue distribution, physiological roles, and in the extent they affect

actin dynamics. ADF/cofilins bind to ADP-G-actin with 10–50 fold higher affinity than to the ATP-G-actin3,4,5,6. A similar tendency is retained upon high-affinity cofilin binding to

ADP-state (older filament, higher affinity) as opposed to its inefficient binding to ATP- and ADP-Pi states (younger filament, lower affinity) of F-actin5,7,8,9. ADF/cofilins regulate actin

dynamics by severing actin filaments at the boundaries between bare and coflin-decorated areas under sub-saturating concentrations, while stabilizing F-actin in a new, cofilin-decorated

state upon filament saturation5,10. In vertebrate actins, the severing appears to be mediated by a release of a cation (Mg2+ or K+ under physiological conditions) from a “stiffness” site

between the D-loop and W-loop of two longitudinally adjacent actin subunits11. F-actin severing by ADF/cofilins generates new ends and thereby, in coordination with other proteins (e.g.

twinfilin, Aip1, CAP), overcomes slow depolymerization as the rate-limiting step in recycling of aged actin filaments. Budding yeast and human cofilins share ~38% identity and 59% homology,

while the three human isoforms of ADF/cofilins share 70–81% identity and 83–89% homology. The structure of ADF/cofilins is highly conserved across all eukaryotic species. The core of

ADF/cofilins is comprised of a five-stranded mixed β-sheet and is surrounded by five peripheral α-helices. The secondary structure elements are positioned in the following order:

α1-α2-β1-β2-α3-β3-β4-α4-β5-α5-β6. The C-terminus of cofilins is folded in a compact β6-strand, which distinguishes it from a less tightly packed C-terminus of ADF12; this difference is

translated to a lower affinity of the latter to F-actin. Structural and mutagenesis studies as well as mapping with synchrotron irradiation and chemical cross-linking12,13,14,15,16 converged

to realization that ADF/cofilins interact with actin via two major areas called G/F- and F-binding sites. The former is involved in binding to both monomeric and filamentous actin and is

mainly composed of the N-terminal residues, and the kinked α4-helix. The N-terminus contains a major regulatory residue Ser3, whose phosphorylation by LIM kinase17 strongly inhibits binding

of cofilins to G- and F-actin, as do point mutations at the N-terminus and in the α4-helix12,18,19. The F-actin binding site does not interact with G-actin, but is essential for binding to

actin filaments; respectively, mutations in this region (e.g. K96Q12) do not affect binding to monomeric actin, but block the ability of cofilin to affect F-actin dynamics. The unique role

of ADF/coflins in actin dynamics is directly linked to its ability to induce dramatic structural perturbations in F-actin. Cofilin binding to F-actin promotes relative reorientation of the

actin subunits leading to a change in a helical twist of the filament20, and an increase in its torsional and bending flexibility21,22. Cofilin modulates filament interaction with actin

binding proteins via direct competition/cooperation, via allosteric influences, or both23,24,25,26. Recent cryo-EM reconstruction studies13 revealed that reorientation of actin subunits is

required to avoid steric clashes between the α1- and α4-helices of cofilin with actin subdomains 1 and 2 (SD1 and SD2), respectively. Thus, binding of cofilin causes a rotation of the outer

domain of actin (comprised of SD1, 2) and weakens the interface between SD1 and SD2 of the longitudinally adjacent actin subunits. While these studies yielded key insights, advanced

understanding of cofilin-actin interaction and the molecular mechanism of cofilin-based actin remodeling requires atomic level structural information on these complexes, which is currently

lacking. In this report, we present atomic-resolution structural analysis of the muscle isoform of human cofilin (CFL2), bound to the α-skeletal isoform of mammalian F-actin, by magic angle

spinning (MAS) NMR spectroscopy. The three isoforms of mammalian cofilins are indispensable and vary in distribution in normal and diseased tissues3,27,28, abilities to support cellular

activities29,30, and in their affinities for G- and F-actin3,9,31,32. Among these, only CFL2, the muscle-specific isoform of ADF/cofilins, was characterized in complex with F-actin by

cryo-EM reconstruction at 9 Å resolution13, and therefore, was selected for this study. MAS NMR spectroscopy, which is emerging as a mainstream structural biology technique, has been applied

to studies into cytoskeleton protein assemblies, such as determination of atomic-resolution structure and dynamics of CAP-Gly domain assembled with polymerized microtubules33,34, and an

investigation of the polymorphism of myelin basic protein associated with actin microfilaments35. We have determined the chemical shifts and the secondary structure for the majority of

cofilin residues. Using chemical shift perturbation analysis in conjunction with double-REDOR (dREDOR) filtered methods36, we have delineated the cofilin residues forming the interfaces with

F-actin as well as residues that are affected allosterically. The outstanding spectral resolution enabled characterization of the cofilin/actin interactions with unprecedented level of

detail. The study presented here opens doors for atomic-resolution structural characterization of assemblies formed by F-actin with cofilin/ADF family and other ABPs. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

RESONANCE ASSIGNMENTS OF COFILIN IN COMPLEX WITH ACTIN FILAMENTS The negatively stained TEM image of the NMR sample containing U-13C,15N human CFL2 in complex with F-actin is shown in Fig.

1c. Formation of CFL2/F-actin complex was confirmed by cosedimentation and SDS-PAGE (Fig. 1d). To corroborate that MAS NMR conditions do not interfere with the sample morphology, TEM images

were collected prior to and after the NMR experiments. Spinning of the samples for extended periods of time does not appear to have any effect on the sample morphology. The samples of

CFL2/F-actin complexes yield outstanding-resolution MAS NMR spectra, as shown in Fig. 2. For resonance assignments of cofilin in complex with actin filaments, a combination of 2D and 3D

homo- and heteronuclear correlation MAS NMR spectra were acquired at 19.96 T using non-uniform sampling (NUS). As shown in Fig. 2a,b and Table S1 (Supplementary Information), remarkably high

spectral resolution of 2D and 3D spectra permitted _de novo_ resonance assignments of 111 out of 166 residues. Figure 2b displays a backbone walk from D9-N16 using 3D NUS NCOCX and NCACX

datasets. The majority of backbone resonances are present in the spectra with the exception of termini residues (M1, P165, L166), several sequence stretches in loop regions spanning residues

K30–K34, V72-D79, G130-Q136, and random individual residues throughout the sequence (Fig. 2c and Table S1). These assignments were also corroborated by comparison with solution shifts of

free cofilin. INTERMOLECULAR INTERFACE AND ALLOSTERIC CHANGES IN COFILIN UPON BINDING TO F-ACTIN To determine the intermolecular interface of CFL2 in complex with F-actin, we have pursued

two approaches: (i) chemical shift perturbation analysis, and (ii) dREDOR-filter-based experiments allowing for a direct determination of intermolecular dipolar contacts between cofilin and

actin filament. This combined analysis yields information on the intermolecular interface and on residues experiencing allosteric changes as the result of the complex formation. To probe

conformational changes in CFL2 upon binding to F-actin, we have analyzed chemical shift perturbations (CSPs) in free cofilin vs. its complex with F-actin. Since atomic-resolution structure

of CFL2 is not yet available, all residues identified in the present study were mapped onto the structure of homologous human CFL1 (PDB 1Q8G) and compared with the cryo-EM reconstruction of

CFL2/F-actin complex13. The results, summarized in Fig. 3, suggest that the previous assumption that cofilin binds to F-actin as a rigid body are incorrect. Indeed, very large chemical shift

perturbations (>2 ppm) are observed for over 27% of all residues, particularly those at the N-terminus (residues S3, G4, V5, T6), in α1-helix (residues D9, V11–V14, K19-R21), β2- and

β3-strands (residues L40, Q46, A52, Q54, L55), α3–helix (residues D66, T69, S70), β4- and β5-strands (residues D79, T88, L99-F101, F103), α4–helix (residues K114, I116, S119, S120, D122,

A123, I124, K125, K127), the 310 helix (D141), and loop residues (D43, K44, V57, T129, and I142) (Fig. 3). Among these, the α4–helix residues K114, I116, I124, K125, K127 were previously

identified to exhibit CSPs upon interaction with G-actin12, while most others appear to be specific for binding to F-actin. There are only few residues with strong G-actin induced CSPs12

that do not show or show only minor, less than 1 ppm differences, upon binding to F-actin, and most of them are either not conserved between the two cofilins (e.g., A/V137, C/G139 in CFL1/2,

respectively) or located nearby the non-conserved residues (e.g., the E134 preceding the non-conserved L/Y135). Since all three residues are located at the actin interface, these changes

may contribute to difference in actin-binding properties between CFL1 and CFL29. The above strong chemical shift perturbations indicate that the corresponding residues either comprise the

intermolecular interface with F-actin or undergo allosteric conformational changes upon formation of the complex. To discriminate between those possibilities and identify cofilin residues

located at the interface with F-actin, we employed a dREDOR filtered approach33. In this method, simultaneous 1H-13C/1H-15N REDOR filter dephases all cofilin protons that are directly bonded

to either 13C or 15N atoms (i.e., 1H belonging to the U-13C, 15N-cofilin). The remaining protons, belonging to the interface regions of unlabeled actin, are then used to transfer

magnetization to cofilin through 1H-15N or 1H-13C cross polarization across the intermolecular interface followed by HETCOR or CORD mixing. The resulting spectrum contains specific

information about the residues forming intermolecular interface. We note that dREDOR based experiment is the only approach to identify intermolecular interfaces when chemical shift

perturbations are small, such as in cofilin/actin complex here or CAP-Gly/microtubule complex studied by us previously33. To perform residue assignments of cofilin residues at the interface,

this experiment is implemented as a 2D dREDOR-CORD sequence (Fig. 4a). G/F-ACTIN BINDING SITES ON COFILIN The dREDOR-based measurements reveal both the G/F- and F- binding sites on the

cofilin surface (representing binding to subunits _“n”_ and _“n + 2”_ in the filament, respectively) to previously unprecedented level of detail. On the basis of the dREDOR-CORD experiment,

we confirmed that the G/F-binding site includes the N-terminus (residues S3, G4 and V6) and the N-terminal half of the bent α4-helix (residues M115 and I116) preceding the kink.

Interestingly, the entire actin-binding surface of the α4-helix appears to be shifted towards its C-terminus as compared to that observed in the crystal structure of G-actin with an

ADF/cofilin homology domain represented by the C-terminal domain of twinfilin14, thus far the only atomic resolution structure of actin-cofilin complex available. Indeed, the N-terminal

residues of the α4-helix that constitute the essential part of the G/F-binding site in the C-twinfilin structure (266-IRER-269 corresponding to 111-LKSK-114 in human CFL2) are not present in

the dREDOR-CORD spectra. On the other hand, the data indicate that residues A123, I124, K127, T129 at the C-terminal part of the kinked α4-helix, which are not at the G-actin/C-twinfilin

interface, are part of the interface in the CFL2/F-actin complex. Residues located in the corresponding part of the α4-helix of budding yeast cofilin were found by mutagenesis to be

essential for cofilin function _in vivo_18 and were recognized to be affected upon binding to G-actin in synchrotron oxidation experiments15 and in solution NMR studies12, see Fig. 5. The

fact that strong signals corresponding to these residues are found in dREDOR spectra suggests that actin is directly involved in interaction with the terminal part of the α4-helix. It

remains to be determined whether the differences observed in the various studies reflect variations in actin-binding modes between the ADF-homology domains of C-twinfilin and cofilin, or

between interaction of cofilins with G- vs F-actin, or even between binding of cofilin to ATP- (the X-ray structure) vs ADP-actin (present work). It is also possible that these additional

residues contribute to a new F-actin binding site, by being possibly involved in binding to the D-loop of a longitudinally adjacent actin subunit (_“n + 2”_), as it can be speculated based

on the proximity of these elements in the cryo-EM reconstruction of F-actin with CFL213. According to the dREDOR results, other residues that might contribute to the G/F-site (i.e. to

binding to the _“n + 2”_ subunit in the filament) are L40, S41, Q46, A105, A109, V137, N138, which overall is in agreement with previous findings12,14,15,18. F-ACTIN BINDING SITES ON COFILIN

To date, the most comprehensive data on the F-site composition originated from a restrained refinement model obtained by fitting atomic-resolution structures of CFL1 (PDB 1Q8G) and actin

(PDB 2BTF) to a 9 Å resolution cryo-EM map density of human CFL2 with rabbit skeletal actin13. The dREDOR-CORD spectra (Fig. 6) are in excellent agreement with the cryo-EM reconstruction

data, and reveal the three major patches of the F-site (to subunit _“n + 2”_ in F-actin) (Fig. 6). The first patch is defined by residues 19–21 (also recognized in the cryo-EM study) and

24–26. It is reasonable to speculate that the latter patch can be involved in binding to the N-terminus of actin as these elements are proximal to each other in the cryo-EM reconstruction13.

The loop comprised by residues 24–32 is present in vertebrates, from fish to human, but not in drosophila, yeast, or plant cofilins. This loop contains a nuclear localization signal (NLS)

essential for active translocation of G-actin-cofilin complexes to the nucleus37. Involvement of the 24–32 loop in interaction with F-, but not G-actin, suggests a possible mechanism of

discriminative recognition of free cofilin and actin-cofilin complexes by nuclear importins. Furthermore, phosphorylation of S23 and/or S24 by PKCα reduces ability of cofilin to bind F-actin

and to modify actin dynamics both _in vitro_ and _in vivo_38. Given a highly acidic nature of actin’s N-terminus, it is reasonable to suggest an electrostatic repulsive mechanism for such

inhibition. Therefore, this site represents regulation at the F-actin level, as opposed to the G/F-level regulation via phosphorylation at S3. The second patch of the F-site is composed of

residues 91, 93–96, and 99, 100 (residues 94–98 in the cryo-EM study) within the loop connecting β4-β5 strands and the N-terminal half of β5-strand. The third patch encompasses residues 153,

157–160, and 163 at the C-terminus of cofilin (defined as residues 154–158 by Galkin _et al_.13.). It was speculated that overall tighter folding and stronger binding of this regions to

F-actin defines the major structural and functional differences between cofilin and ADF12. In addition to these well-defined patches, dREDOR spectra revealed residues T63, T69, S70, which

are located at the surface opposite to actin binding sites. As illustrated in Fig. 3, the majority of the residues experiencing large CSPs are either present in the dREDOR spectra or are

directly neighboring them corroborating the finding that these residues are located at the interface with F-actin. Among few cofilin residues with large chemical shift perturbations that are

not in proximity of residues in dREDOR spectra, V57 (~8 ppm), D141, V143 (4–6 ppm), C80 (~2 ppm), and T88 (>2 ppm), are particularly notable (see Fig. 3). Their unusually large CSPs

correlate with localization in loops (V57, C80 and T88) and, therefore, likely reflect flexibility of the corresponding loop regions, or with localization at the actin-cofilin interface

(D141, I143) not identified by the dREDOR spectra. Indeed, D141 and D142 of CFL2 correspond to E141 and E142 in CFL1 sequence. This difference was recently implicated as a likely source of

different affinities of the two cofilins to ATP-actin9. In addition, high CSP of C80 likely reflects changes in the oxidation state of this residue (reduced in free cofilin and oxidized in

complex with actin, according to the 13Cα/Cβ chemical shifts39). Additional insights into the nature of the changes described by the large chemical shift perturbations will be gained from

the atomic-resolution MAS NMR structure of CFL2 bound to actin, which is forthcoming. CONCLUSIONS We reported atomic-resolution structural investigation of the human CFL2 complex with

F-actin, by MAS NMR spectroscopy. Using a combination of chemical shift perturbation analysis and dREDOR-based methods, we have determined the cofilin residues comprising the interfaces with

F-actin as well as residues affected allosterically. The outstanding spectral resolution enabled characterization of the cofilin/actin interactions with unprecedented level of detail.

Broadly, MAS NMR approach reported here is applicable to the analysis of actin-binding proteins bound to filamentous actin that otherwise are not amenable to atomic-resolution studies

through other current techniques. METHODS MATERIALS 15NH4Cl and U-13C6 glucose were purchased from Cambridge Laboratories, Inc. Common chemicals were purchased from Fisher Scientific or

Sigma-Aldrich. EXPRESSION AND PURIFICATION OF U-13C,15N-COFILIN Tag-less full-length human CFL2 (cloned between NcoI and BamHI sites in pET15b vector (Novagen)) was expressed in _Escherichia

coli_ BL21-CodonPlus(DE3) (Agilent Technologies). Transformed bacterial cells were grown at 37 °C in 4 L of rich medium (1.25% tryptone, 2.5% yeast extract, 125 mM NaCl, 0.4% glycerol, 20

mM TRIS-HCl (pH 8.2)) supplemented with 50 μg/mL ampicillin and 34 μg/mL chloramphenicol to OD600 1-1.2. Bacteria were pelleted, washed in MJ medium40 without addition of glucose and

ammonium chloride, resuspended in 0.75 L of MJ medium without glucose and NH4Cl and incubated on a shaker for 1 h at 25 °C. Following this incubation, the bacterial cell suspension was

supplemented with U-13C6 glucose (4 g/L final concentration) and 15NH4Cl (1 g/L final concentration) and expression was induced with 1 mM IPTG. Cultures were grown overnight at 25 °C. Cells

were pelleted at 4 °C, resuspended in ice-cold buffer A (10 mM PIPES, pH 6.8, 0.5 mM EDTA, 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 5 mM benzamidine, protease inhibitor

cocktail (Sigma)), and lysed using French cell press. Sequential anion and cation exchange chromatography was used to purify isotopically labeled cofilin. Cell lysate was cleared by

centrifugation at 40,000 g for 30 min at 4 °C and loaded onto a DE52 (DEAE cellulose, Sigma) column followed by an SP-sepharose (Sigma) column connected sequentially. The columns were

disconnected and the protein was eluted from SP-sepharose column with a gradient of 50 to 500 mM NaCl in buffer A. Fractions containing cofilin were combined and further purified using

size-exclusion liquid chromatography (SEC FPLC) in a buffer containing 10 mM PIPES, pH 6.8, 25 mM KCl, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 0.4 mM EGTA, 0.1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. PREPARATION OF

F-ACTIN Skeletal muscle G-actin was prepared from acetone powder of rabbit skeletal muscle (Pel-Freeze Biologicals) as previously described41 and stored in G-buffer (5 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0,

0.2 mM CaCl2, 0.2 mM ATP, 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol). G-actin was switched from Ca2+- to Mg2+-bound state by 10-min incubation with 0.1 mM MgCl2 and 0.4 mM EGTA and polymerized by addition of

buffer containing 20 mM PIPES, pH 6.8, 25 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol. PREPARATION OF U-13C,15N-COFILIN/F-ACTIN COMPLEX For the preparation of MAS NMR samples, U-13C,15N-CFL2

and F-actin were mixed at a 1:1.2 molar ratio and centrifuged at 90,000 rpm (RCF 435,400 g) at 4 °C for 1 hour in a TLA 120.2 rotor using a Beckman Coulter Optima MAX-XP ultracentrifuge

following overnight incubation on ice. The gel-like pellet was transferred into a 1.9 mm Bruker rotor. 14.3 mg of hydrated U-13C,15N-cofilin/actin complexes containing an estimated 3 mg of

isotopically labeled cofilin were packed into 1.9 mm Bruker rotors. TRANSMISSION ELECTRON MICROSCOPY The U-13C,15N-cofilin/actin sample morphology was verified by transmission electron

microscopy (TEM). Actin samples were stained with uranyl acetate (5% w/v), deposited on 400 mesh, formvar/carbon-coated copper grids, and dried. The TEM images were acquired by a Zeiss Libra

120 transmission electron microscope operating at 120 kV. SOLUTION NMR SPECTROSCOPY Solution NMR spectra were acquired on a 14.1 T (1H Larmor frequency of 600.1 MHz) Bruker AV spectrometer

using a triple-resonance inverse detection (TXI) probe. All spectra of U-13C,15N-cofilin were recorded at 298 K. Backbone and Cβ resonance assignments of U-13C,15N cofilin were carried out

using heteronuclear 2D 1H-15N HSQC and 3D HNCACB, HNCA, HNCO, HNCACO at 298 K. MAS NMR SPECTROSCOPY MAS NMR spectra were acquired on a 19.96 T Bruker AVIII instrument using a 1.9 mm HCN

probe. The Larmor frequencies were 850.4 MHz (1H), 213.8 MHz (13C) and 86.2 MHz (15N). The MAS frequency was 14 kHz, controlled to within ±10 Hz by a Bruker MAS controller. The temperature

was calibrated using KBr as the temperature sensor. The actual temperature at the sample was 273 K and maintained to within ±0.1 °C using a Bruker temperature controller. 13C and 15N

chemical shifts were referenced with respect to the external standards adamantane and NH4Cl, respectively. Dipolar-based 2D and 3D NCACX and NCOCX experiments were acquired using non-uniform

sampling (NUS). The random exponentially weighted NUS schedules were employed, see Supplementary Information42,43. The 3D spectra were acquired with 25% NUS using 48 complex points in the

t1 and t2 indirect dimensions, with maximum evolution times of 3.4 ms and 6.9 ms for 13C and 15N, respectively. The spectra were processed using the MINT reconstruction protocol42. The

signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) of the 2D NCACX and NCOCX were 14 and 13, respectively. The SNR for the 2D 13C-13C CORD is 15. The first contour level was set to 5X the noise level for all

spectra. The uncertainties in the solid-state chemical shifts are ±0.3 ppm. The typical 90° pulse lengths were 2.75 μs, 2.95 μs for 13C, and 3.3 μs for 15N. The 1H-13C and 1H-15N CP employed

a linear amplitude ramp for 80–100%: the 1H RF field was 91 kHz; and the center of the ramp on the 13C or 15N was Hartmann-Hahn matched to the first spinning sideband. In 2D and 3D NCACX

experiments, the RF field strengths were 64.9 kHz, 84.7 kHz and 91 kHz for 15N, 13C and 1H channels, respectively. The DARR mixing sequence was applied to the 1H channel and the DARR mixing

time was 50 ms. The 1H decoupling powers were 90–100 kHz during acquisition and evolution periods in all experiments. For 2D 13C-13C CORD correlation experiments44, the typical 90° pulse

lengths were 2.55 μs for 1H, and 2.3 μs for 13C. The 1H-13C CP employed a tangent amplitude ramp of 80–100%, the 1H RF field was 75 kHz, and the center of the ramp of the 13C Hartmann-Han

matched the first spinning sideband. The RF field on the 1H channel was matched to the MAS frequency (14 kHz) and one half of it (7 kHz) during the 50 ms mixing time. The typical decoupling

power was 90–100 kHz during the acquisition and evolution. The spectral width was 299.75 ω2 and 213.83 in ω1 with the carrier frequency set to 96.2 ppm. The double-REDOR (dREDOR) filtered

experiments on U-13C,15N-CFL2 bound to F-actin employed simultaneous 1H-13C/1H-15N REDOR dephasing periods of 714 μs, to eliminate signals from 1H (all protons in CFL2) directly bound to 13C

and 15N33. The CP contact time was 5 ms and the CORD mixing time was 50 ms. To rule out the possibility that certain signals in the dREDOR based spectra may be artifacts arising from

dynamic residues due to insufficient suppression of 1H spin polarization, control experiments were conducted as described in our report45. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION HOW TO CITE THIS ARTICLE:

Yehl, J. _et al_. Structural Analysis of Human Cofilin 2/Filamentous Actin Assemblies: Atomic-Resolution Insights from Magic Angle Spinning NMR Spectroscopy. _Sci. Rep._ 7, 44506; doi:

10.1038/srep44506 (2017). PUBLISHER'S NOTE: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. REFERENCES * Pollard,

T. D. & Cooper, J. A. Actin, a central player in cell shape and movement. _Science_ 326, 1208–1212 (2009). Article CAS ADS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Bernstein, B. W.

& Bamburg, J. R. ADF/cofilin: a functional node in cell biology. _Trends Cell Biol._ 20, 187–195 (2010). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Vartiainen, M. K. et al.

The three mouse actin-depolymerizing factor/cofilins evolved to fulfill cell-type-specific requirements for actin dynamics. _Mol. Biol. Cell_ 13, 183–194 (2002). Article CAS PubMed PubMed

Central Google Scholar * Blanchoin, L. & Pollard, T. D. Interaction of actin monomers with Acanthamoeba actophorin (ADF/cofilin) and profilin. _J. Biol. Chem._ 273, 25106–25111

(1998). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Andrianantoandro, E. & Pollard, T. D. Mechanism of actin filament turnover by severing and nucleation at different concentrations of

ADF/cofilin. _Mol. Cell_ 24, 13–23 (2006). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Ressad, F. et al. Kinetic analysis of the interaction of actin-depolymerizing factor (ADF)/cofilin with G-

and F-actins. Comparison of plant and human ADFs and effect of phosphorylation. _J. Biol. Chem._ 273, 20894–20902 (1998). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Carlier, M. F. et al. Actin

depolymerizing factor (ADF/cofilin) enhances the rate of filament turnover: implication in actin-based motility. _J. Cell Biol._ 136, 1307–1322 (1997). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central

Google Scholar * Muhlrad, A., Pavlov, D., Peyser, Y. M. & Reisler, E. Inorganic phosphate regulates the binding of cofilin to actin filaments. _FEBS J._ 273, 1488–1496 (2006). Article

CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Kremneva, E. et al. Cofilin-2 controls actin filament length in muscle sarcomeres. _Dev. Cell._ 31, 215–226 (2014). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central

Google Scholar * Suarez, C. et al. Cofilin tunes the nucleotide state of actin filaments and severs at bare and decorated segment boundaries. _Curr. Biol._ 21, 862–868 (2011). Article CAS

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Kang, H. et al. Site-specific cation release drives actin filament severing by vertebrate cofilin. _Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA_ 111, 17821–17826

(2014). Article CAS ADS PubMed Google Scholar * Pope, B. J., Zierler-Gould, K. M., Kuhne, R., Weeds, A. G. & Ball, L. J. Solution structure of human cofilin: actin binding, pH

sensitivity, and relationship to actin-depolymerizing factor. _J. Biol. Chem._ 279, 4840–4848 (2004). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Galkin, V. E. et al. Remodeling of actin

filaments by ADF/cofilin proteins. _Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA_ 108, 20568–20572 (2011). Article CAS ADS PubMed Google Scholar * Paavilainen, V. O., Oksanen, E., Goldman, A. &

Lappalainen, P. Structure of the actin-depolymerizing factor homology domain in complex with actin. _J. Cell Biol._ 182, 51–59 (2008). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar *

Guan, J. Q., Vorobiev, S., Almo, S. C. & Chance, M. R. Mapping the G-actin binding surface of cofilin using synchrotron protein footprinting. _Biochemistry_ 41, 5765–5775 (2002).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Grintsevich, E. E. et al. Mapping the cofilin binding site on yeast G-actin by chemical cross-linking. _J. Mol. Biol._ 377, 395–409 (2008). Article

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Yang, N. et al. Cofilin phosphorylation by LIM-kinase 1 and its role in Rac-mediated actin reorganization. _Nature_ 393, 809–812 (1998).

Article CAS ADS PubMed Google Scholar * Lappalainen, P., Fedorov, E. V., Fedorov, A. A., Almo, S. C. & Drubin, D. G. Essential functions and actin-binding surfaces of yeast cofilin

revealed by systematic mutagenesis. _EMBO J._ 16, 5520–5530 (1997). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Moriyama, K. & Yahara, I. The actin-severing activity of

cofilin is exerted by the interplay of three distinct sites on cofilin and essential for cell viability. _Biochem. J._ 365, 147–155 (2002). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google

Scholar * McGough, A., Pope, B., Chiu, W. & Weeds, A. Cofilin changes the twist of F-actin: implications for actin filament dynamics and cellular function. _J. Cell Biol._ 138, 771–781

(1997). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Prochniewicz, E., Janson, N., Thomas, D. D. & De la Cruz, E. M. Cofilin increases the torsional flexibility and dynamics

of actin filaments. _J. Mol. Biol._ 353, 990–1000 (2005). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * McCullough, B. R., Blanchoin, L., Martiel, J. L. & De la Cruz, E. M. Cofilin increases

the bending flexibility of actin filaments: implications for severing and cell mechanics. _J. Mol. Biol._ 381, 550–558 (2008). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Ge, P.,

Durer, Z. A., Kudryashov, D., Zhou, Z. H. & Reisler, E. Cryo-EM reveals different coronin binding modes for ADP- and ADP-BeFx actin filaments. _Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol._ 21, 1075–1081

(2014). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Robaszkiewicz, K., Ostrowska, Z., Marchlewicz, K. & Moraczewska, J. Tropomyosin isoforms differentially modulate the

regulation of actin filament polymerization and depolymerization by cofilins. _FEBS J._ 283, 723–737 (2016). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Skau, C. T. & Kovar, D. R. Fimbrin

and tropomyosin competition regulates endocytosis and cytokinesis kinetics in fission yeast. _Curr. Biol._ 20, 1415–1422 (2010). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar *

Grintsevich, E. E. & Reisler, E. Drebrin inhibits cofilin-induced severing of F-actin. _Cytoskeleton_ 71, 472–483 (2014). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Mohri, K. et al.

Expression of cofilin isoforms during development of mouse striated muscles. _J. Muscle Res. Cell Motil_. 21, 49–57 (2000). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Wang, Y. et al.

Differential expression of up-regulated cofilin-1 and down-regulated cofilin-2 characteristic of pancreatic cancer tissues. _Oncol. Rep._ 26, 1595–1599 (2011). CAS PubMed Google Scholar *

Tahtamouni, L. H., Shaw, A. E., Hasan, M. H., Yasin, S. R. & Bamburg, J. R. Non-overlapping activities of ADF and cofilin-1 during the migration of metastatic breast tumor cells. _BMC

Cell Biol._ 14, 45 (2013). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Gurniak, C. B., Perlas, E. & Witke, W. The actin depolymerizing factor n-cofilin is essential for

neural tube morphogenesis and neural crest cell migration. _Dev. Biol._ 278, 231–241 (2005). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Nakashima, K. et al. Two mouse cofilin isoforms,

muscle-type (MCF) and non-muscle type (NMCF), interact with F-actin with different efficiencies. _J. Biochem._ 138, 519–526 (2005). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Yeoh, S., Pope,

B., Mannherz, H. G. & Weeds, A. Determining the differences in actin binding by human ADF and cofilin. _J. Mol. Biol._ 315, 911–925 (2002). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Yan,

S. et al. Atomic-resolution structure of the CAP-Gly domain of dynactin on polymeric microtubules determined by magic angle spinning NMR spectroscopy. _Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA_ 112,

14611–14616 (2015). Article CAS ADS PubMed Google Scholar * Yan, S. et al. Internal dynamics of dynactin CAP-Gly is regulated by microtubules and plus end tracking protein EB1. _J.

Biol. Chem._ 290, 1607–1622 (2015). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Ahmed, M. A. M. et al. Induced Secondary Structure and Polymorphism in an Intrinsically Disordered Structural

Linker of the CNS: Solid-State NMR and FTIR Spectroscopy of Myelin Basic Protein Bound to Actin. _Biophys. J._ 96, 180–191 (2009). Article CAS ADS PubMed Google Scholar * Gupta, R.,

Hou, G., Polenova, T. & Vega, A. J. RF inhomogeneity and how it controls CPMAS. _Solid State Nucl. Magn. Reson._ 72, 17–26 (2015). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar *

Munsie, L. N., Desmond, C. R. & Truant, R. Cofilin nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling affects cofilin-actin rod formation during stress. _J. Cell Sci._ 125, 3977–3988 (2012). Article CAS

PubMed Google Scholar * Sakuma, M. et al. Novel PKC alpha-mediated phosphorylation site(s) on cofilin and their potential role in terminating histamine release. _Mol. Biol. Cell_ 23,

3707–3721 (2012). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Martin, O. A., Villegas, M. E., Vila, J. A. & Scheraga, H. A. Analysis of (13)C(α) and (13)C(β) chemical shifts

of cysteine and cystine residues in proteins: a quantum chemical approach. _J. Biomol. NMR_ 46, 217–225 (2010). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Jansson, M. et al.

High-level production of uniformly (1)(5)N- and (1)(3)C-enriched fusion proteins in Escherichia coli. _J. Biomol. NMR_ 7, 131–141 (1996). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Spudich, J.

A. & Watt, S. Regulation of Rabbit Skeletal Muscle Contraction. 1. Biochemical Studies of Interaction of Tropomyosin-Troponin Complex with Actin and Proteolytic Fragments of Myosin. _J.

Biol. Chem._ 246, 4866-& (1971). * Paramasivam, S. et al. Enhanced Sensitivity by Nonuniform Sampling Enables Multidimensional MAS NMR Spectroscopy of Protein Assemblies. _J. Phys. Chem.

B_ 116, 7416–7427 (2012). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Suiter, C. L. et al. MAS NMR of HIV-1 protein assemblies. _J. Magn. Reson._ 253, 10–22 (2015). Article CAS

ADS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Hou, G. J., Yan, S., Trebosc, J., Amoureux, J. P. & Polenova, T. Broadband homonuclear correlation spectroscopy driven by combined

R2(n)(v) sequences under fast magic angle spinning for NMR structural analysis of organic and biological solids. _J. Magn. Reson._ 232, 18–30 (2013). Article CAS ADS PubMed PubMed

Central Google Scholar * Guo, C., Hou, G., Lu, X. & Polenova, T. Mapping protein–protein interactions by double-REDOR-filtered magic angle spinning NMR spectroscopy. _J. Biomol. NMR_,

1–14 (2017). Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We acknowledge the support of the National Science Foundation (NSF Grant CHE0959496) for the acquisition of the 850 MHz NMR spectrometer at

the University of Delaware and of the National Institutes of Health (NIH Grants P30GM103519 and P30GM110758) for the support of core instrumentation infrastructure at the University of

Delaware. AUTHOR INFORMATION AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of Delaware, Newark, 19716, Delaware, USA Jenna Yehl & Tatyana Polenova *

Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, The Ohio State University, Columbus, 43210, OH, USA Elena Kudryashova & Dmitri Kudryashov * Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University

of California, Los Angeles, 90095, CA, USA Emil Reisler * Molecular Biology Institute, University of California, Los Angeles, 90095, CA, USA. Emil Reisler Authors * Jenna Yehl View author

publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Elena Kudryashova View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Emil

Reisler View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Dmitri Kudryashov View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google

Scholar * Tatyana Polenova View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CONTRIBUTIONS T.P., D.K. and E.K. designed the study; E.K. and D.K. prepared

the samples and conducted cosedimentation study; J.Y. acquired the NMR spectra, conducted the TEM sample characterization, NMR data analysis, and prepared the manuscript figures; J.Y., D.K.,

E.K., E.R. and T.P. wrote the manuscript. CORRESPONDING AUTHORS Correspondence to Dmitri Kudryashov or Tatyana Polenova. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS The authors declare no

competing financial interests. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION (PDF 685 KB) RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0

International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the

material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Yehl, J., Kudryashova, E., Reisler, E. _et al._ Structural Analysis of Human Cofilin

2/Filamentous Actin Assemblies: Atomic-Resolution Insights from Magic Angle Spinning NMR Spectroscopy. _Sci Rep_ 7, 44506 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep44506 Download citation *

Received: 09 December 2016 * Accepted: 08 February 2017 * Published: 17 March 2017 * DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep44506 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will

be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt

content-sharing initiative