Play all audios:

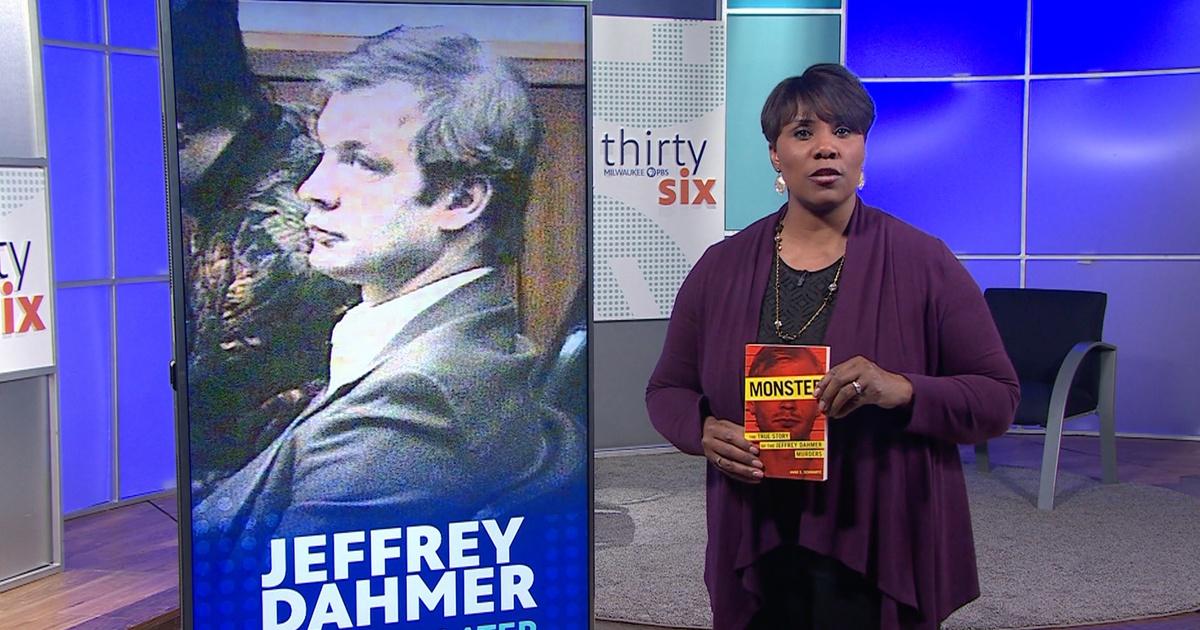

(gentle music) (upbeat music) - Serial killer Jeffrey Dahmer committed the murder and dismemberment of 17 men and boys. Former "Milwaukee Journal" crime reporter Anne E. Schwartz

was the first reporter on the dramatic scene at 25th and Kilbourn the night of July 22nd and early morning July 23rd, 1991. Dahmer was later killed in prison by inmate Christopher Scarver in

1994. She's written two books on the case, her latest coming out later this month. It's titled "Monster: The True Story of the Jeffrey Dahmer Murders." Anne E. Schwartz

talked with "10thirtysix" producer Maryann Lazarski about the case, and why she's writing about it again, 30 years later. - Could you just explain how you got this tip? You

were the first reporter, right, to know about what was happening. How you got the tip, and once you got to 25th and Kilbourn, what did you see? What did you witness? What happened? - I was

the part-time crime reporter at the "Milwaukee Journal," which is the least enviable position in a newsroom, probably. And what I was good at as a reporter, which I feel like is a

lost art anymore, was making sources, was getting cops to trust you to tell you things. I never imagined that I would get a call from one of those sources on July 22nd, 1991, saying,

"Annie, you gotta get over here. There's a guy that's been saving body parts in his apartment, and Ralph found a head in the refrigerator." So I'm taking this all

in, and the source just said, "Just better get here." So my first inclination was to think somebody's having some fun with me. It's one of the cops that I know, that I

work with, who's just trying to have some fun with me to tell me something that's not really true and get a rise out of me at, you know, 11:30 at night. But something in his voice

told me that I should get out there. So I went out to the scene by myself, to 25th and Kilbourn, right in front of the Oxford Apartments. It was very early. There was I think only one

detective squad there, if they were even there yet. But I walked up to the scene, I walked into the apartment building, and I walked up to the floor where Jeffrey Dahmer's apartment

was, which was the second floor. It was apartment number 213, and I stepped inside. I didn't take a tour, right? This was not in a parade of homes. I walked in the door and just, I

looked around, because I was looking to see what was happening, what does this look like? I eventually went back outside because I knew that I was gonna get in trouble for being there. And I

had conversations with the neighbors, and it was obvious from the minute I got to the scene that this was a different crime scene. This was unlike any other crime scene I had covered.

People were so quiet, and they were almost fearful. They were taken aback by what they were seeing and hearing, and the rumors were starting to get out about a head in the refrigerator,

about body parts in the apartment, about the way the place smelled, and all of these things are starting to happen, and I am beginning to interview and have conversations with people that

lived in the building, who are standing outside in their, you know, in their bathrobes and their slippers, just kind of with their arms just pulled to their chest, and talking to me about

this. There is a part of me that feels like that might've been the last genuine interviews that people gave about that case, because it became so huge, that it wasn't just Anne E.

Schwartz from the "Milwaukee Journal." By the next day, it was "Inside Edition." It was "Oprah." It was "Phil Donahue." It was pick a show. Everyone

was showing up and wanted to know about this story. And the stories became more and more embellished as time went on. But I was always very proud of the work that I and the rest of the

reporting team did that very first night, when we were trying to figure it all out. We could have gotten it very wrong, because the details were so horrific. What if some of those things

were being made up, right? So that was how that all began, was that I showed up, I talked to people who were standing there. I'd been to enough crime scenes, so I knew what it would

look like. I was also the only reporter there at that time. I was the only reporter on that scene for maybe a couple hours. - When I was working at WISN, you know, our overnight producer got

on the air by one o'clock in the morning to report what was happening, and so we had a crew probably around 12:30, but, you know, again, it's one of those things like what? You

know, what do you mean, a head in a fre- In Milwaukee? This is happening, right? - Nothing happens here. That was all of the, it's like, oh, this is a story that happens in California

or Florida or somewhere else. It just wasn't something that happens here, 'cause this is the Midwest, and we have good German, Polish heritage, and we're church-going people,

and all of those kinds of things that make the Midwest just kind of vanilla. And we really lost our innocence that year, when more and more about that story came out. - It shook the city to

its core. It really did. I mean, people, after a while, they didn't even want to hear about it anymore. I mean, it was so, you know, details were sickening, the families were grieving.

And in newsrooms, certainly, you know, we're trying to decide what's the ethical thing to do? How do we present this? What do we say? Even our graphics, you know, what should it

say? - What can we say? - Right, tell us about this first book that you wrote on Jeffrey Dahmer, "The Man Who Could Not Kill Enough." This was after court? - This book was my first

book, and it takes the reader, it's written in the first person, so it's my experience going through the case. As is the new book, which is also my experience going back 30 years

to the case as well. - Why did you feel compelled to write a book about a case that you've been covering and covering and covering, you felt like you needed to? - I had covered the case

from day one. I was the reporter that broke the story, which means when I go and speak, by the way, at schools and universities and classes and things, that the young people in the class

think that means I tweeted first. And we have to tell them that's not what that means, but I'd written two stories that first day. The first one was very much a kind of a

here's what we know, very factual, but then I also wrote another story, and it started, "In a neighborhood inured to crime, this was something different." And I wrote a whole

mood piece on what the crime scene felt like. Well, that ran in a national media outlet, and I was contacted by a publisher that asked if I wanted to write a book on the case. And, you know,

you really don't say, "Well, this wasn't really what I dreamed of. I was kind of hoping for, you know, for something else, something a little more palatable." But this

was the story, and why do we get into journalism in the first place? To tell the story. And so I took the opportunity to tell the story. 30 years later, I get a call from a publisher, who

said, "What do you think of, it's been 30 years. What do you think about going back?" And that's what I did in the new book, in "Monster." I went back and found

all the principals from the case, those that are still alive, those that will still talk, and said, "How did this case impact you 30 years later?" - [Maryann] Can you give us just

one or two examples of people you talked to and how did it impact them? What are they thinking 30 years later? Do they just want Dahmer to go away and never bring it up again? - The people

who were principals in the case, the detectives that worked the case, the medical examiner, the district attorney at the time, Jerry Boyle, who was Dahmer's defense attorney, all of

those people, including myself, found a value in talking about the case with professional groups. I spoke to journalism groups, and Jerry Boyle and the DA spoke to law schools, and this has

become a case for presentation with the National Association of Medical Examiners. I mean, there was a value in all of us talking about the case. - [Maryann] What was the value, though? -

The value was, what have you learned in 30 years? What has it taught you? How did it affect you? Remember that this case was all about, oh my God, it's awful, it's disgusting, tell

me more. - [Maryann] So how did it affect, let's say, a detective you might've talked to or a family member? - So Mike Dubis was one of the detectives. He was the first detective

on the scene, and I talked to him about it, and I'm always shocked when cops tell me that there is something that sticks with them, because I always think of them as such a hardy,

sturdy bunch, who just are able to go to these horrible scenes that would horrify most of us and do their job, do their work. So Mike Dubis said, "You know what, Annie?" He said,

"Everything will be fine, and then I'll be walking past, like in a building, I'll be walking past where somebody's using like a cleaning fluid that reminds me of what I

smelled in the apartment that night." And he said it really startles him, and it does give him pause. It gives him a minute. - That's one of the things that I marked in the book,

'cause as we were talking earlier about what you remember or what kind of sparks that memory again, and when he talked about, you know, he's been around death a lot. But the smell

wasn't death, it was that sweet chemical smell. - It was, and that's an important piece. That's a really important piece, because everyone was asking, from the cops who came

to the building months before, to the neighbors, they were like, "Didn't that smell like a dead body?" Well, no, it didn't. - What about a family member? Do they even

still want to talk about it? - No. That's the short answer. Families are not interested in continuing to talk about this. There is one woman whose brother was killed by Dahmer, and one

of the things that Dahmer confessed to is that all of the victims were gay, and that he was able to seduce all of them to come back to his apartment with him. Now, not only do you find out,

so he's not throwing a pillowcase over somebody's head and dragging them out of a bar. So not only are these families learning that their loved one was killed by a serial murderer

in this most horrible way, but they also, some of these families, found out that their loved one had a private life, had a secret life. So one of the men who was found to have been a victim

of Dahmer's, his sister, to this day, you cannot mention my name in front of her, because she says, "My brother was not gay. You don't know what you're talking about.

Somehow Dahmer kidnapped him, somehow it happened, but this, absolutely not true." And I can't even imagine, to find out all of this information at once. There were family members

that felt that anyone that wrote a book on this case should have given them money. I don't think that the family members understood that this is not, most of the people that wrote books

on this case, I wasn't the only one, there were people that did the quick books that came out, some of them during the trial, they were coming out. The families were trying to find a

way to be compensated for this loss. And that was tough, 'cause there just, there wasn't anything there, there was nothing there from him, from his family. So that was a challenge

for some of the people involved in that case. - If you can go back to race relations, because I think there are a lot of people who don't understand what the race relations involved

back then, and it's a very important topic, even now, in how police are handling certain situations. So what happened with regard to race relations back then, and how did the police

handle, mishandle? - I'm hearing a lot of people bringing up the Dahmer case now, in retrospect, when they're talking about current events in policing, and oddly, I had not thought

of it in that way, because to me, there were very different, there were very different circumstances. The hardest thing when you talk about going back and looking at how police interacted

with a certain community, and you go back 30 years plus, because these murders happened in the '80s and the early '90s, when you go back that far, you're doing it with the

knowledge that you shouldn't do this, or you should do this, or how you should be looking for this. I still speak to one of the officers that was involved in the Dahmer case. I still

speak to one of the officers who turned Konerak Sinthasomphone back to Jeffrey Dahmer. - [Maryann] So if people don't know who Konerak was... - Konerak Sinthasomphone was a 14-year-old

boy that Jeffrey Dahmer met and offered money for sex when he met the boy at a mall. Konerak came back to the apartment with him, Dahmer drugged him, and then ran out to get more beer. Well,

the boy woke up while Dahmer was gone, ran out of the apartment, was running up the alley when a neighbor called the police and said, "There's a boy naked, and he's running

up the alley." So the police came. Dahmer comes back from the liquor store and talks to the police, and what people just can't wrap their brain around, because the easiest thing to

do is to say, "Ah, these cops didn't care." But that's not true. That's not the case. Dahmer was a master manipulator. It's how he killed 17 people without

being detected. He was a master manipulator, he talked to the officers in this very calm manner. Konerak, the young boy, does not look like he's 14 years old, because I saw the pictures

that Dahmer had taken of him that night, as did the officers. The story is, there's so many pieces of the story that can still be told about that night and their interaction with

Dahmer. But the bottom line is that Dahmer convinced them that the two were lovers, and the officers went with Konerak and with Dahmer back upstairs to Dahmer's apartment, where

Konerak's clothes were folded neatly, and there were Polaroids of Konerak in his underwear posing for Dahmer. The police officers saw all of this and said, "They're a

couple." People forget, there wasn't probable cause for them to search that apartment. If they had, they would have found the body of another victim in the other room. - But people

also thought that if Konerak was a white male. - Absolutely. That has become the narrative now. The narrative has become, for some, that Jeffrey Dahmer was able to get away with what he did

because of white privilege and because of police incompetence. And I think that you can make an argument for and against both of those things. If you have never sat in a room and had a

conversation with a serial killer, which most people haven't, you'd be surprised that they're not like Charles Manson. You're not talking to someone whose pupils are

doing spirals and they have a swastika carved in their head. You're looking at somebody that looks like the neighbor, and he was masterful at his manipulation. - What lessons did we

learn, or still need to learn? - Look how we've come full circle on this today. We're talking about issues of community trust. We're talking about how officers interact with

the gay community. How do they interact with the Hmong community? How do they interact with the Black community? These are all, now we're having all these conversations, but when you

look back at that time, and you look at what we all had in front of us at the time, if you look what those officers had in front of them at the time, you really would have to say, "No,

they did not have a Magic 8 Ball." We wish they would have. They didn't. They wish they would've, and they didn't. - Today you travel the world and talk to police

departments, right, all over the world. Communication, crisis communication, strategic planning. Does this case come up, and if so, what does this, and your latest book, how does that affect

what you tell them, what they ask you? What have you learned that you'd pass on to these different police departments, and how do they look at Milwaukee? And not just Dahmer, but even

today, we have a huge violent crime problem. So if you could just talk a little bit about that. - Other countries, I think look at the United States when it comes to our procedures, our

legal procedures, when it comes to the way that we do strategic communication, they look at us as the best practice. But when they look at us societally, they ask what's going on. They

don't really understand. We also have to remember that the way that other countries, law enforcement in other countries works is not the same way that it works here. Things happen in

other countries that would never be allowed here, and if they happened here, they would be huge news. Whether it is the beheading of journalists, or whether it is how press freedom works, or

doesn't work. But I think that's the view, the view of the United States is that we, for the most part, and the places that I travel to in Europe, in Central and Western Europe,

people say, "Oh, the US said to do it this way, so we're gonna do it this way." But they also, the people I think that criticize what happened during the Jeffrey Dahmer case,

and the legacy of that case here, are going to be people from the United States, who look and say, "How could you guys not know? What kind of a place is Milwaukee?" And then the

jokes come. You know, Milwaukee's biggest image problem before Jeffrey Dahmer was that people didn't like that we were associated with "Laverne and Shirley" and

"Happy Days," and oh, that's not a sophisticated image from the city, brats and beer. After Jeffrey Dahmer, they would take brats and beer and "Laverne and Shirley"

any day. - Do you think the city has erased the Jeffrey Dahmer image or memory? Or is it always gonna stick with Milwaukee? - I think that the image is always going to stick with Milwaukee,

because when someone introduces me as the person who wrote the book on Jeffrey Dahmer, when I get introduced as an expert on the case, people in Wisconsin are not clamoring to ask questions.

Everywhere else I go, they are. But people here very, very personally took the smack at our reputation. They took that very personally. I think that that is, that's a very painful

period in the city's history, and it's one a lot of people would like to forget, but our history is our history, good or bad. The area where the Oxford Apartments were at 25th and

Kilbourn, that is still vacant, because the building eventually was razed, and then the land is there, and there were talks that "Let's make it something good for the neighborhood.

Let's build a park. Let's do something." Some people wanted it to be a memorial to some of the victims. The people who live in that neighborhood want nothing to do with that.

They say, "You can build a playground, but I'm never gonna have my kid play in there, 'cause the devil lives in there, the devil lives in the dirt in there." And so

there's a giant wrought iron fence around the property, and it's being used for nothing. It just is overgrown and sits there like a pockmark on the street. - [Maryann] You think

that will ever change? - I don't know. I'd like to have a good answer for that. I'd like to be able to say, you know, eventually, here's what I think will happen there,

but it's been 30 years. We have memorials built where Timothy McVeigh bombed the Murrah building in Oklahoma City. We have a memorial there. We have memorials in New York City for the

attacks on 9/11. Serial killers, typically you just don't make a memorial for that. People come to Plainfield because they want to see Ed Gein's grave, right. Maybe they want to

see Gacy's grave, or try to find out where his murders happened. But typically when it comes to serial murder, people aren't erecting monuments. It's not something people want

to remember. - Do you ever think, "Gosh, I wish I wasn't the expert on Jeffrey Dahmer"? - I never imagined that this would be how I would be remembered, introduced, thought

of. And frankly, it's a little strange to be associated with with this case. But I think it's important that we tell the truth about this case. People come out of the woodwork and

say, "Hey, I remembered him when I went to grade school with him," or "Oh, I remember this." There has to be someone who's telling the truth about these cases,

whether it's me talking about the Jeffrey Dahmer case, whether it's Robert Rand writing about the Menendez brothers. Whatever it might be, there has to be somebody who is telling

the truth and is able to talk about the case in the way that people actually want to, which is what have we learned, where are we going, what did we do, how did this happen, how was this

allowed to happen, could this happen today? These are all the questions people want to ask. - It's Anne E. Schwartz. - [Portia] For more on the Dahmer case, go to Milwaukeepbs.org.

(upbeat music)