Play all audios:

_IN THIS COLUMN, MEMBERS OF GEORGIA HUMANITIES AND THEIR COLLEAGUES TAKE TURNS DISCUSSING GEORGIA’S HISTORY AND CULTURE, AND OTHER TOPICS THAT MATTER. THROUGH DIFFERENT VOICES, WE HEAR

DIFFERENT STORIES._ _This week guest contributor WILLIAM D. BRYAN, a Georgia State University professor of environmental history, explores the concept of “constructive, not destructive,

development” devised by Georgia’s “New South” economic leaders. _ By William D. Bryan It may seem counterintuitive to look to Henry Grady for advice about sustainability. As the famed editor

of the _Atlanta Constitution,_ Grady is best known as the spokesman for a “New South” of industrialism and urbanization after the Civil War — a vision that depended on intensively using

valuable resources like soil, timber, and minerals to fuel economic growth. The poor environmental legacies of New South development are still evident, especially in Atlanta, where they are

memorialized by deep gullies cutting through red clay fields, rivers full of chemicals, snarled traffic, urban sprawl, and cutover forests. Although Grady and his fellow boosters are

typically cast as the villains who sold the South’s environment away for short-term gain, they were never as short-sighted as this narrative implies. In fact, southern leaders worried that

valuable resources were being depleted too quickly and desperately looked for more sustainable ways of using them — hoping to put the region on the path of long-term economic growth. They

called this idea “permanence.” The logic of it seemed simple: an industry could be permanent if it managed natural resources instead of exploiting them to depletion, and permanent

enterprises quickly became the ideal for officials working to rebuild the region’s economy. The best explanation of permanence came from Robert Lowry — a contemporary of Grady’s and one of

Atlanta’s most prominent business leaders. As the president of a bank that depended on economic growth, Lowry hoped to provide for his business by promoting ways of using resources that

would leave the southern landscape in “better shape” for later generations. In 1913 he explained that southerners should adopt a more “conservative use of natural resources, which results in

constructive and not destructive development.” With this strategy, Lowry believed that “the natural resources of this wonderful section, in which our thriving city of Atlanta is located,

can be turned into permanent productive sources of wealth for this and all future generations.” Simply put, economic and environmental permanence could be realized by finding enterprises

that promoted “constructive and not destructive development.” Lowry was not a nature lover. He was a hard-nosed businessman with little interest in nature preservation measures that might

hamstring industries. Though focused on the bottom line, he understood that profit and environmental quality did not have to be mutually exclusive goals. Rather than cordoning off land in

state or national parks, forcing businesses to change their ways through legislation, or establishing effective state-level conservation commissions, booster organizations and state

officials used permanence to target private enterprises that would manage the region’s resources rather than exploiting them to depletion. By the mid-20th century, boosters had made great

strides in attracting industries they considered permanent. Commercial fertilizers, pulp and paper manufacturing, cottonseed oil production, and tourism were only a few of these supposedly

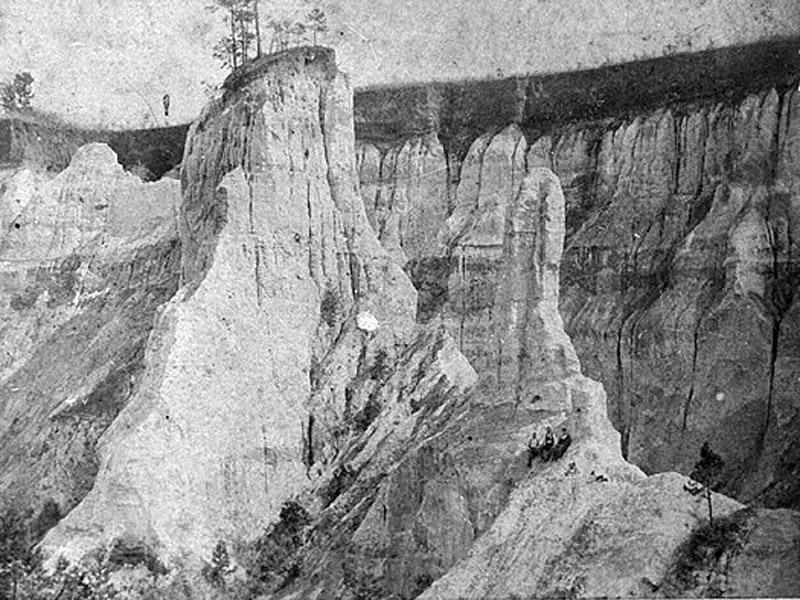

permanent enterprises. Yet this success never translated into the sustained growth or environmental permanence that officials hoped for. Instead, the South became a cautionary tale about the

consequences of unchecked development — a point evident in denuded landscapes like Providence Canyon in west Georgia and underscored by writers like Erskine Caldwell. The problem was not

that permanence had failed, but that it had succeeded. Permanent enterprises provided a way to secure long-term stocks of industrial resources without having to rein in business or rethink

the way that firms operated. Efforts to achieve permanence sometimes even made environmental problems worse by intensifying resource use or creating unexpected problems. Manufacturing paper

required forest management but created water and air pollution; replanting forests with slash pine simplified complex ecosystems; fertilizers temporarily boosted soil fertility at the

expense of soil health; tourism preserved scenic landscapes but paved the way for sprawl. These problems did not figure into the strategy of southern officials. By defining conservation as

the permanent use of resources, then, New South leaders like Grady and Lowry found a goal that they could work toward without checking development or addressing other pressing environmental

issues. To me, permanence sounds a lot like sustainable development. Popularized in the 1980s, sustainable development is just the newest strategy for balancing economic growth with the

limitations of nature, and both concepts share a belief that environmental problems can be solved with developmental solutions. So, can Henry Grady teach us about sustainability? I think so.

But perhaps not the lessons we expect. Rather, the South’s struggle for economic and environmental permanence more than a century ago should provide a note of caution about our own notions

of sustainability. History suggests that efforts to act more sustainably cannot effectively address pressing environmental problems as long as we measure sustainability with the metric of

continued economic growth. Our efforts may even make these problems worse. DR. WILLIAM D. BRYAN is an environmental historian who teaches at Georgia State University. He is completing a

book, entitled _The Price of Permanence: Nature and Business in the New South_, which explores how nature conservation and permanence shaped the American South after the Civil War. Find out

more about his work at www.williamdbryan.net. _Kelly Caudle and Allison Hutton of Georgia Humanities provides editorial assistance for the “Jamil’s Georgia” columns._ _RELATED POSTS_