Play all audios:

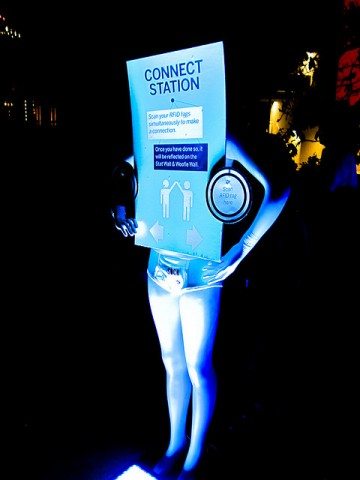

George Orwell might say a big ol’ “told ya so” if he could see the Texas schools keeping tabs on their students with wireless devices today. Last fall, San Antonio’s Northside ISD began

issuing radio-frequency identification (RFID) enhanced student IDs to help with its attendance records. Austin began a small opt-in RFID program last fall, and in 2010, two Houston-area

districts began tracking kids with RFID. The trend has gotten national attention. Rep. Lois Kolkhorst (R-Brenham) wants to end the practice. On Tuesday, her bill outlawing mandatory RFID

student tracking got its day before the House Public Education Committee. Like the most outspoken critics of RFID tracking—whose worries range from civil liberties to religious

convictions—her co-authors on the bill are an unlikely bunch, from Fort Worth Democrat Lon Burnam to freshman Bedford Republican Jonathan Stickland. The bill would let school districts use

RFID tracking, but would protect any student who wanted to opt out. Big Brother would need permission to watch if you’re cutting class. Northside ISD’s insistence that students participate

is the subject of a federal lawsuit, brought by Andrea Hernandez, a student told she had to wear the RFID badge at John Jay High School. Hernandez was joined by her father at the Capitol

Tuesday, as she offered her support for Kolkhorst’s bill. She told committee members the device made her feel sick, and that she was made to wear the badge despite her religious objections.

Her father, Steven Hernandez, said his daughter’s principal offered to let her wear a badge without the RFID, but only if the family didn’t tell other students. Hernandez’ father said he

still worries that wearing the badge threatened the family’s salvation. “He wanted her to wear it around the neck and fall in line,” he said. “That’s like taking the ‘mark of the

beast.'” Hernandez was referencing a prophecy in the Book of Revelation, referring to marks the Antichrist will make before the end of the world: > “And he causeth all, both small

and great, rich and poor, free and > bond, to receive a mark in their right hand, or in their foreheads: > > And that no man might buy or sell, save he that had the mark, or the

> name of the beast, or the number of his name.” Northside’s RFID badges aren’t so exotic in origin at all—they’re locally produced by San Antonio-based Wade/Garcia and Associates, and

owner Michael Wade was on hand to defend his product. Wade said he’d studied for the priesthood, in fact, and wouldn’t consider his product the “mark of the beast” at all. “I can’t imagine

it would damage or hurt anyone,” he said. Wade said the devices don’t emit radiation—which Hernandez said affected her health—and the battery-powered device runs on very low power. Wade said

the devices don’t really track students, but create “a cookie trail” of the last place the students were when a scanner picked up their device. “After awhile they would know if someone was

using this tag if it was in the library when they should be in the gym,” Wade said. School districts that use the devices say they’re useful safety measures, particularly in emergencies, and

can help lead to higher attendance counts—which means more funding from the state. Still, support for outlawing RFID requirements is wide-ranging—from the American Civil Liberties Union,

for instance, to the conservative Virginia-based Rutherford Institute, which represents Hernandez in the suit against Northside. Heather Fazio, executive director of Texans for Accountable

Government, told lawmakers today that RFID tracking makes her concerned for family members who have no way to opt out if their schools start using the technology. “I find it to be appalling

to track children like inventory and livestock,” she said. For now, the bill is pending in the House Public Education Committee.