Play all audios:

In 2019, the Parliamentary authorities suspended the Labour MP Keith Vaz from the Commons for six months. Conservative MPs did not complain. In 2020, the Conservative MP Conor Burns was

suspended for a week. Again, there were no complaints, just as there was no government complaint when David Laws, the Liberal Democrat MP, Paul Flynn, the Labour MP and Ian Paisley Jnr, the

DUP MP were all suspended from parliament. All of these suspensions, it should be noted, occurred under a Conservative government. But now, Owen Paterson, the Conservative MP has caused the

government to leap into action. Paterson was investigated by the Parliamentary authorities, which found he had lobbied government on behalf of two companies that were paying him. That is

against the rules. For a full explanation of what Paterson did and why the parliamentary committee that oversees MPs behaviour found him in breach of the rules, this speech by Chris Bryant,

who chairs that committee, gives the evidence and reasoning in detail. Bryant’s speech is quietly damning. It makes clear that Paterson broke the rules. It also explains why the decision to

suspend Paterson from the Commons for 30 days was justified. And yet, despite the clearest possible evidence that Paterson did lobby government on behalf of companies that were paying him,

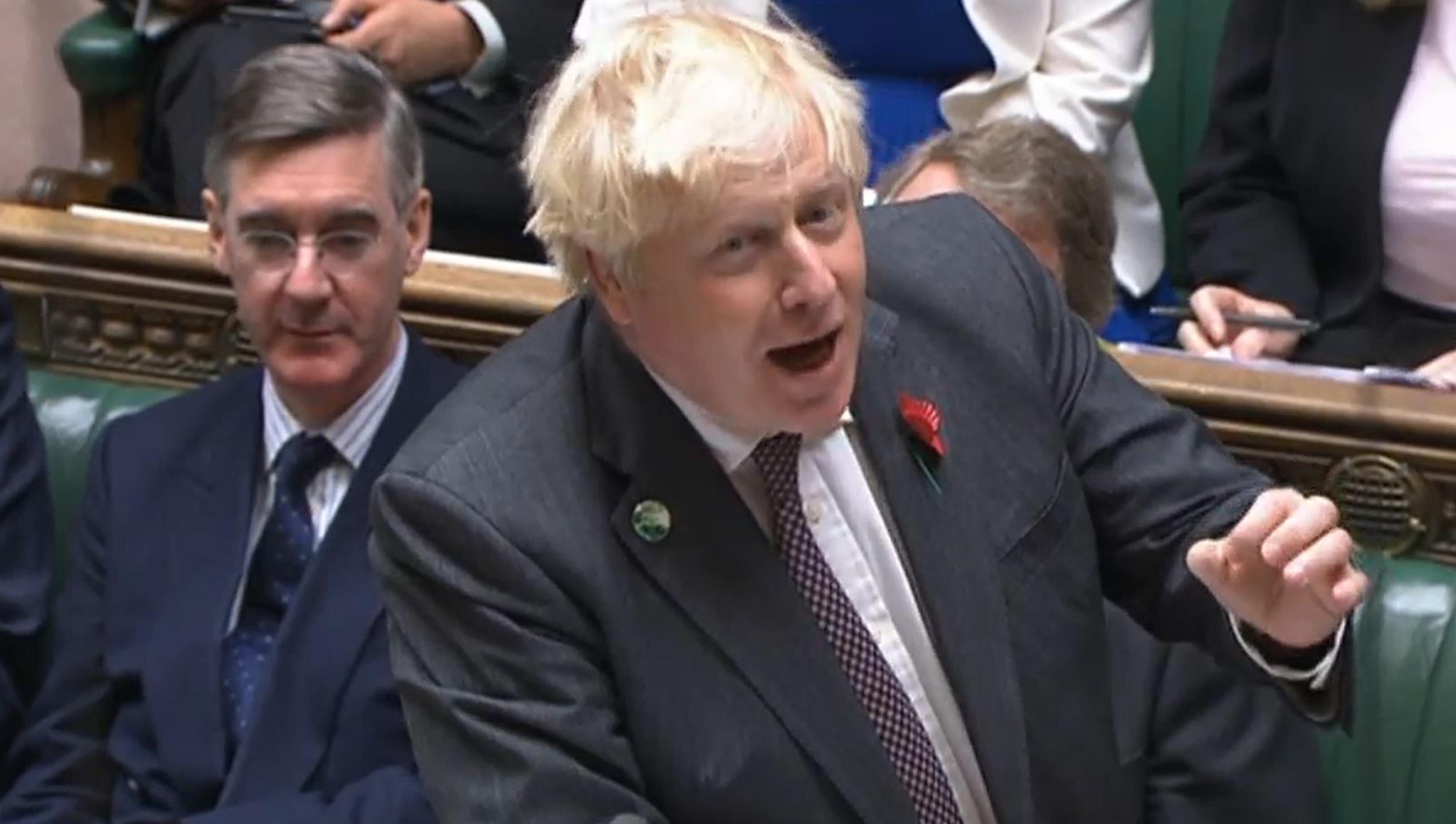

No10 decided to attack the process. Suddenly, despite having been in government for a decade, Conservatives said that now was the time to reform the system overseeing the behaviour of MPs.

Paterson became the focus of a huge government effort at exculpation. A marginal vote in the Commons yesterday went in Paterson’s favour. Despite having broken the rules on lobbying,

Paterson got off. What should we make of all this? Is it corruption? Or is it, as the government has attempted to argue, a necessary re-writing of the rules on MPs’ behaviour? No10 has

suggested, and Paterson has argued, that MPs currently have no right of appeal. A decision is made on whether they have broken the rules, and they have no ability to contest it. This

systemic wrinkle, even if it existed, which it does not, would seem an odd point on which to stake so much political capital. Because the government has placed quite a few of its chips on

saving Paterson, even though many people would be hard pressed to pick him out of a crowd. Why has No10 done this? The most likely assumption is that most people simply don’t care about any

of this. Parliamentary procedure is, on the whole, arcane, boring and ridiculous. If an MP no one has ever heard of has broken some obscure rule no one cares about, then sure, why not bend

the rules a little in order to get him off? And if the Today programme gets a little hot under the collar about it all, so what? That calculation is, perhaps, the most likely explanation as

to why No10 acted as it did. It’s true, these political bun-fights can often remain obscure, of interest only to obsessive Westminster types — but occasionally an obscure Parliamentary fight

can begin to take on broader significance. The Paterson scandal is just the latest in a long line of stories all of which seem to locate No10 at the centre of an increasingly cosy

chumocracy, in which “donors” pay for the refurbishment of the Prime Minister’s residence, and “donors” pay for the Prime Minister’s holiday to Mustique, and where friends of ministers win

contracts to supply medical equipment, often without any competitive tendering process and so on and so on. And if the inhabitants of this cosy political in-group get into trouble, they are

well cared for. Priti Patel, for example, faced no censure when Parliamentary authorities investigated allegations of bullying and found evidence that she had broken the ministerial code.

And no one in government seemed especially bothered when it turned out Robert Jenrick had helped Richard Desmond in a planning application that ended up saving Desmond millions. Paterson, a

former minister and hard Brexiteer, risked being put out into the cold, and once again the inner circle sprang into action. The Government even went so far as to issue a three-line whip,

effectively ordering MPs to vote in favour of an amendment that would get Paterson off the hook. Other scandals, including the accusations of bullying leveled at Priti Patel, were

complicated, the charges diffuse. But the Paterson scandal is not diffuse. The trouble for No10 is that the story is so clear: Parliament investigated and concluded that Paterson took cash

for access and the government then bent the rules to save him. There’s no complexity there, no complicated stories about who said what to whom. Most people may not care very much about the

ebb and flow of Westminster, but they know corruption when they see it. And what we have seen at Westminster in the last few days is corruption. The government has decided that the rules

need to change now that one of its own has broken them. The PM has stepped in to save the career of a mate. That is corrupt. There’s no getting away from it. And people are not stupid. They

can see what’s going on.