Play all audios:

Somehow, I cannot work up any excitement at all about the so called world championship match, currently in progress in Kazakhstan. With the reigning champion, Magnus Carlsen, sulking like

Homer’s Achilles in his tent, refusing to compete, yet declining to retire, the once proud title of world chess champion has forfeited its accustomed lustre. Indeed, what I have seen of the

run of play so far, fails to inspire confidence that the two Pretenders, vying for the withered laurels, are anything more than that. Ding’s handling of the opening as White, in game two ,

with its feeble early h3, is sad evidence that Carlsen’s presence, in defence of his title, is more than sorely missed. No amount of F IDÉ (World Chess Federation) hype can convince me that

this lamentable show does not herald the possible death knell of the championship, as we have known it, since its official inception in 1886. I have even seen photos of the empty hall,

devoid even of the players, with a caption claiming how excited the would-be audience might be, at the mere prospect of attending such an historic event. In fact, my chief interest has, of

late, focused on events involving a reigning and a future champion, from 1966 . Then, to paraphrase Douglas Adams’ Hitchhikers’ Guide to the Galaxy , men were men, women were women, and

small furry creatures from Alpha Centauri were small furry creatures from Alpha Centauri. But first let me set the scene, with some important background information. Tigran Petrosian, the

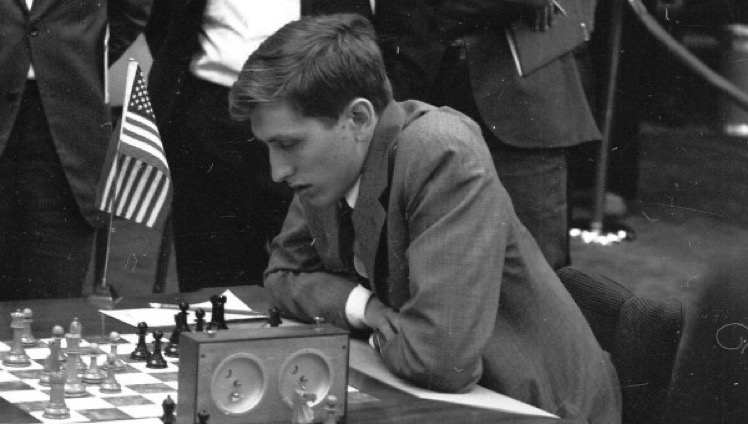

wily Grandmaster from Armenia, had just defeated his fellow Soviet challenger Boris Spassky, to become the first reigning champion to win a title match since 1934. Meanwhile, a rampant Bobby

Fischer was actively staking his future claim to the title, while the Danish grandmaster Bent Larsen, having annihilated Petrosian in two games from a tournament in Santa Monica ( the first

with a crushing queen sac ), was about to embark on a triumphal tournament procession — the best year of his life. 1967 was, indeed, to become Larsen’s annus mirabilis. All of the above,

not to mention the author of this column, had assembled in the latter part of 1966 for the Havana Olympiad, or world team competition. This huge event was presided over by the cigar-smoking

Cuban revolutionary dictator, Fidel Castro, with whom I and the other team members enjoyed several official dinners and other functions. It should be added that, of all his numerous

accolades, Fischer never had, nor would, win the Olympiad gold medal for the best score on top board. In his various Olympiad appearances , the gold always eluded him, going in 1960 to

Mikhail Tal, in 1962 to Fridrik Olafsson, and in 1966, as we shall see, to Petrosian. In Fischer’s final Olympiad outing, 1970, it went to the then world champion Boris Spassky, who crushed

The American Meteor in their mano a mano game. At the 1966 Olympiad in Havana, where Petrosian garnered the first of his golds, it was openly said that he ducked his most dangerous

opponent, Bobby Fischer. Meanwhile, Fischer who had been on course himself to win the gold medal, overreached himself at the last moment. The American lost to the nervous but talented

Romanian Grandmaster Florin Gheorghiu — thus, the story goes, letting Petrosian sneak past at the final post. The truth, though, is somewhat different. For the USA v USSR match the initial

line-up was indeed Fischer v Petrosian. I was there, I saw the name cards and I know wh y that game never took place . What happened was this: because of some footling complaint by Fischer,

involving the half-baked timetable of some new age religious cult to which Fischer had temporarily subscribed, the USA team failed to show up and was defaulted. Petrosian, therefore, through

no conniving of his own, had won the first round, beating Fischer by default when the American top board simply did not appear for the game. Generously, however, adhering to the principle

of noblesse oblige, the USSR allowed a replay at a later time, originally designated as a free day. Petrosian, meanwhile, had become involved in various lengthy adjournments. He may also

have been understandably reluctant to replay a game he had already won by default. It will be recalled that Boris Spassky, when defending his world crown against Fischer six years later in

the Reykjavik Match of the Century, was perfectly happy to accept a default when Fischer was a no-show for game two. Certainly Spassky was gentleman enough not to claim the entire match at

this stage, which he might well have done, but his decision to pocket the whole point from the game Fischer had defaulted evoked no criticism from any quarter. I know from experience that it

is psychologically very difficult to replay at full strength a game you have already won . Spassky knew that in 1972 and Petrosian knew it also in 1966. Returning to Havana, with the USA

given a second chance, the USSR rested Petrosian and wheeled out Spassky on top board, a draw against Fischer being the ultimate outcome. What is also overlooked, apart from Petrosian’s

undoubted initial willingness to meet Fischer, was that Bent Larsen was actually considered by the Soviets the main threat to Petrosian at the time, having not long beforehand twice beaten

the World Champion in the Piatigorsky Cup. Larsen was indeed about to embark on a fabulous series of tournament victories which almost brought him to the very top. Petrosian, however,

refused to duck this challenge and came out fighting against Larsen with Black, determined to win. For the World Champion this game – and not the unplayed one against Fischer – must have

seemed the supreme challenge of the entire Olympiad, with his reputation as world champion riding on the result. A win for Petrosian would have been sweet revenge and a vindication of his

status as number one. A third consecutive loss, on the other hand, to the same opponent, would have been a disastrous blow to his prestige. Had Petrosian been animated by cowardly or base

motives, this surely would have been the game and the opponent to avoid. Instead, Petrosian achieved a nerve-wracking win with his patent exchange sacrifice. And what of the game between

Larsen and Fischer from Havana – who won that? Well, oddly enough, Fischer, who had also lost a game to Larsen in the Piatigorsky Cup, decided to take a rest that day and allowed another

team member to face the great Dane . Unsurprisingly, the “Bobby was robbed ” lobby failed to stress this inconvenient fact when claiming vociferously that their man should have won the gold

medal . Similar accusations were levelled against Petrosian when he was once more to win the Olympiad gold medal for best personal performance at Lugano two years later . By now the

desperation of his detractors was becoming palpable, if not ludicrous. Petrosian, it was rumoured, had won gold by ducking dangerous opponents, such as … Najdorf. With all due respect to

Miguel Najdorf, a great and imaginative player and for many years Argentine’s finest, by 1968 he was hardly a threat to Petrosian. Indeed, the world champion had made mincemeat of him

before. So his avoidance of Njdorf can doubtless be ascribed to the long-standing Soviet policy of rationing Olympiad games equally between all team members. When the time came for the

pairing USSR v Argentina, it was simply Petrosian’s turn for a day off from the gruelling schedule. Although I was present at Havana, scoring four wins and one loss for England, while I was

still a pupil at Dulwich College, I completely overlooked at the time an important game which exerted an important impact on Fischer’s final score. In fact, I only noticed it last week. This

was the game between Ludek Pachman and Bobby Fischer, from the match between Czechoslovakia and the USA, won narrowly by the Americans, with three draws and this one win. What is striking

about Fischer’s win, which contributed significantly to his gold medal aspirations, was that, to my eyes, Pachman resigned in a hopelessly drawn position. In spite of his extra pawn, neither

I, nor my computer engine, can see any way for Black to win, a fortiori, since endgames featuring bishops of opposite colours, are notoriously drawish. At the very least, resigning in

such a position is almost inexplicable, even if there does exist some recondite and hidden path for Black to make progress. What on earth can be the explanation? Had the boot been on the

Soviet foot, with Pachman resigning such a position against Petrosian, the entire chess world, not least Bobby Fischer himself, would have been up in arms, crying foul. One thing, though, is

clear. Fischer was, like Robespierre, in Carlyle’s memorable phrase, a “sea–green incorruptible”, and would never have stooped to bribery to win a game. Could it have been a secret desire,

on Pachman’s part, to ensure that an American, not a Soviet, won the gold medal? Hardly . Pachman, at that stage of his life, was a staunch Communist. This only changed (and radically so)

with the USSR invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968. In protest, Pachman became an outspoken dissident, only to be imprisoned and tortured. In 1972 he was released and allowed to emigrate to

West Germany. Was the reason for Pachman’s resignation in Havana a feeling of inevitable doom, when facing Fischer? Such forebodings handicapped many of Fischer’s victims. Again, this is

unlikely : Pachman’s lifetime score against Fischer was rather good. Finally, having reached move 40, or thereabouts, in those antediluvian pre-computer analysis days, unfinished games were

routinely adjourned overnight. Thus Pachman would, by adjourning instead of resigning, have enjoyed plenty of time to be persuaded by his colleagues that the Czech match against the USA

could be saved as a tie, if Pachman had soldiered on for a draw, rather than supinely and unnecessarily capitulating. This inexplicable victory presented Fischer with real chances for his

longed for Gold Medal, until he self-combusted against Gh eorghiu , in his solitary loss. (See above.) Some mysteries will never be solved. Why did Pachman resign and why, with adjournment

and friendly team analysis beckoning, was Pachman in such a hurry to give up the ghost? With all parties to this Sherlockian conundrum long since gone, I fear we shall never know. One thing,

though, is clear to me. In spite of Fischer’s otherwise magnificent play at Havana, which I was privileged to observe first hand, I am more than ever convinced that Petrosian’s Olympiad

Board 1 Gold Medal was absolutely justified. In such races, an extra half point is worth its weight in gold. Pachman’s resignation was an extra half point, gifted to Fischer, not one he

earned. I leave you with a puzzle, of sorts… Did Nepomniachtchi miss a win in his first game against Ding Loren? Let me know what you think: Nepomniachtchi vs. Loren (WCC game one) Raymond

Keene’s latest book “Fifty Shades of Ray: Chess in the year of the Coronavirus”, containing some of his best pieces from TheArticle, is now available from Blackwell’s . His 206th book,

Chess in the Year of the King, with a foreword by The Article contributor Patrick Heren, and written in collaboration with former Reuters chess correspondent, Adam Black, is in preparation.

It will be published later this year. A MESSAGE FROM THEARTICLE _We are the only publication that’s committed to covering every angle. We have an important contribution to make, one that’s

needed now more than ever, and we need your help to continue publishing throughout these hard economic times. So please, make a donation._