Play all audios:

When a really bad thing happens to children unexpectedly, the event can change them forever. As a child psychologist, I see firsthand what that means. Traumatized children often try to avoid

thinking about a terrifying ordeal, but the horrible experience nevertheless replays itself in their minds and, as a consequence, in their lives. Sometimes this happens in immediate,

obvious, and direct ways: bad dreams at night, phobias during the day. Other times, the traces of trauma can be delayed, subtle, indirect, and symbolic. An example: One of my patients, Jeff,

repeatedly acted out the same scenario with his action figures. A great battle ensued between the evil warriors and the superheroes. The battle reached the top of a castle where eventually

the evil warriors were thrown over the parapet and died. We might dismiss such play as typical for young boys. Except that for this boy the action, especially the tenacious repetitive nature

of it, seemed to have special significance. In July 2001 he dined with his family at Windows on the World, the revolving restaurant atop the World Trade Center. He now struggled to

integrate this memory with the horrible reality of the collapse of the very structure where he enjoyed himself on vacation. A place of joy transmogrified into a death trap. The same battle

scenario went on for months. Jeff’s dark demeanor during this play was in stark contrast to his pre-traumatic joyful mood during play. His play embodied the three distinct qualities of a

symbolic post-traumatic reenactment: It was long-lasting, repetitive, and grim. Early psychologists who studied trauma were concerned about its negative effects, and not surprisingly that is

what they learned about. But more recent studies have searched for positive outcomes of trauma and have learned what novelists and historians have known for generations: Many people draw

strength from adversity. They take inspiration from their suffering. They transcend their traumas and become better people. Reenactments of childhood traumas can benefit the rest of us when

they reverberate in creative pursuits that go beyond children’s play, such as in art. Horrors from youth creep into an adult’s artwork in the form of recurring themes, literal re-creations

of the original terrifying events, and pervasive dark tones. The result sometimes provides entertainment that appeals to a broad audience. But post-traumatic reenactments speak more

personally to audience members who also have experienced trauma. Years ago I became aware that a particular superhero, who has entertained millions of people, had special appeal to the

traumatized children who visited my office. I had a hunch that a trauma had inspired the creation of this superhero. See if you think my hunch was correct. THE DARK NIGHT His pals nicknamed

him “Doodler” because he was constantly drawing pictures. His pals had nicknames, too—they were fellow members of a neighborhood club know as “The Zorros,” an appellation that a young Robert

Kahn had chosen, inspired by the cinematic crusader for justice played by Douglas Fairbanks, Sr. The Zorros’ clubhouse was built with wood stolen from the neighborhood lumber yard—a place

whose many nooks and crannies made it the location of choice for their games of hide-and-seek. One night, when he was 15 years old, Kahn—who went by “Robbie” at the time—had a terrifying

encounter. Walking home through rough neighborhoods of the Bronx after a music lesson, carrying a violin case, he was followed by “a group of seedy-looking roughnecks from the tough Hunts

Point district,” as he wrote in his autobiography 57 years later: > They wore the sweatshirts of the Vultures, and they were known to be > a treacherous gang. They were whistling at me

and making snide > remarks that only “goils” played with violins. I stepped up my > pace and so did they. Finally, I started running and they did > likewise, until I reached my

neighborhood. Unfortunately, my buddies > were not hanging around the block at the time. Kahn’s memoir goes on to give a very lengthy, melodramatic blow-by-blow account of his dash to the

familiar lumberyard, the Vultures’s pursuit (“with terrifying menace in their eyes”), and his attempts at self-defense, complete with “Zorro” leaps, grappling hook, and mid-air kicks while

swinging on a rope. He fought bravely, he writes, but for naught: > My worst fears came true. Two Vultures pinned both my arms behind my > back and held me firm while another beat a

staccato rhythm on my > belly, knocking the wind out of me. Another bully stepped in and > used my face for a punching bag—while he cracked a couple of my > front teeth. > >

I was in a fog, when I felt my right arm crack at the elbow after a > gang member deliberately twisted it behind me in order to break it. > The pain was excruciating and I screamed in

agony. > > Before I blacked out and fell to the ground like a limp rag doll, I > heard him laugh sardonically, “Just to make sure dat da Fiddler > ain’t gonna play his fiddle no

more!” Little did he know that it > wasn’t playing the violin again that concerned me, but the fact > that he had broken my drawing arm. > > Then he stepped on the hand of my

broken arm! I don’t remember how > long I remained in a blanket of darkness before I regained > consciousness, but when I came to, I was a beaten, bloody wreck. > Somehow I managed

to pull myself up and it was then that I noticed > my violin on the ground, smashed to pieces. This was the coup de > grace! > > This whole episode, to this day, remains in my

subconscious like a > nightmare. I had played Zorro and lost! Had it really been a dream > or a movie, I would have emerged victorious. But this real-life > drama had almost cost

the life of a reckless fifteen-year-old. Here we have a boy who was attacked by a gang of Vultures in the night. He defended himself by playing Zorro, using a grappling hook to fend off his

attackers. He was unsuccessful and was hospitalized, severely injured, with the possibility that he would be unable to pursue his chosen career. In spite of permanent injuries—scars, chipped

teeth, and limited mobility in one arm—he went on to become a cartoonist. Seven years after being brutalized, he created a comic-book superhero that would become a pop-culture legend—and

whose appeal may be deeply, subtly connected to what happened that night in the lumber yard. THE DARK KNIGHT In 1938, the first superhero arrived on the scene—Superman—and the comic book

industry leapt from infancy into what is now known as its golden age. The “Man of Steel” not only changed the course of comic books, he set the course for Robert Kahn’s entire professional

career. Here is how that happened. Superman was a huge commercial success. So one Friday, a DC Comic’s editor asked Kahn, who now used the name Kane and drew slapstick comics, to come up

with his own superhero to complement the Man of Steel. Kane wrote, “Over the weekend I laid out a kind of naked superhero on the page, with a figure that looked like Superman or Flash

Gordon. I placed a sheet of tracing paper over him so that I could create new costumes that might strike my fancy. Then, POW! It came to me in a flash—like the old cliché of an electric

light bulb lighting up over a cartoon character’s head when he has a brainstorm. I remembered Leonardo da Vinci’s drawing of a bat-like flying machine.” And that’s when Bob Kane created

Batman. The opening lines of the first Batman comic strip set the tone for a contemporary myth that has endured for 75 years: “The ‘Bat-Man,’ a mysterious and adventurous figure fighting for

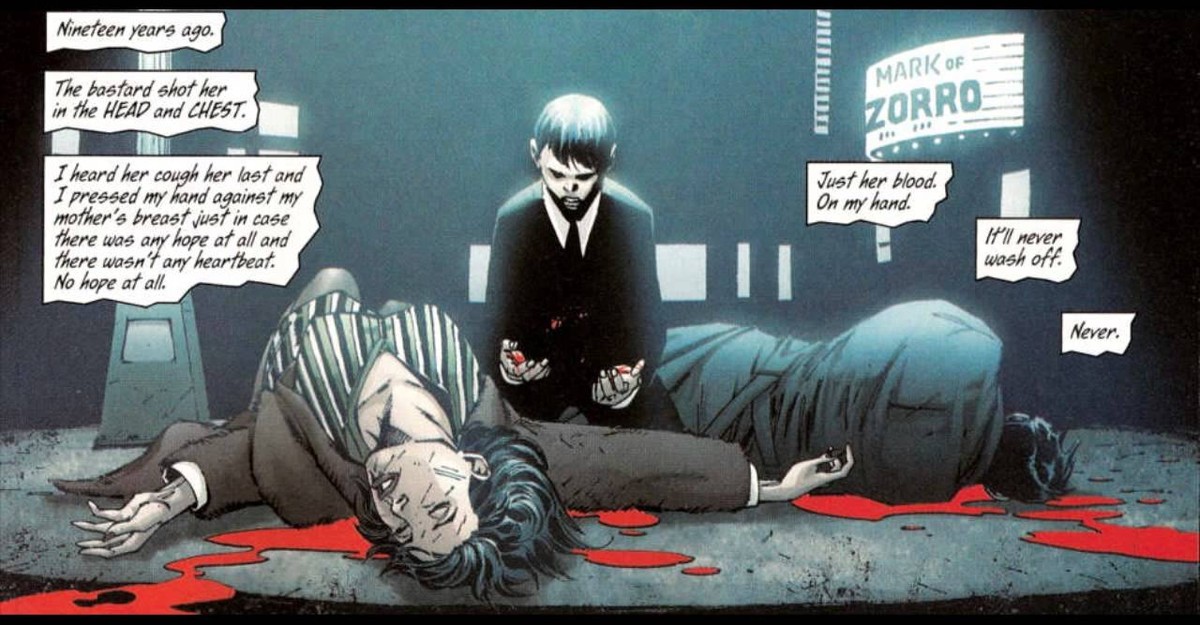

righteousness and apprehending the wrong doer, in his lone battle against the evil forces of society ... his identity remains unknown.” Six issues later we learn what makes the Batman tick:

a terrible trauma. In his youth Bruce Wayne witnessed the brutal murder of his father and mother by a street hoodlum. He vows to avenge their deaths by declaring war on all criminals and

dons the bat cape and cowl to frighten his enemy. “And thus is born this weird figure of the dark … This avenger of evil. The Batman.” Kane recognized three separate influences on the

creation of Batman. The first was da Vinci’s model of a flying machine called the Ornithopter, created about 500 hundred years ago. The second was the movie _The Mark of Zorr_o. “Zorro’s use

of a mask to conceal his identity,” Kane writes, “gave me the idea of giving Batman a secret identity.” The third influence on Batman was a movie Kane saw the year before his attack by the

Vultures: _The Bat Whispers_, an adaptation of a novel by Mary Roberts Rinehart. In the movie a detective tries to track down a mysterious killer, the Bat, and at the end of the film the

detective is revealed to be the killer himself. His black robe and bat-shaped head made him look “very ominous” to Kane. Kane also acknowledged the influence of other movies on what he

called “the dark, mysterioso atmosphere” he tried to evoke in Batman. “Movies like _Dracula_,” Kane writes, “... left an indelible impression on me. The first year of Batman was heavily

influenced by horror films, and emulated a Dracula look.” Kane never acknowledged any link between his attack by the Vultures and his creation of Batman. His conscious purpose in relating

the lumberyard nightmare in his autobiography was to show how close he came to losing his career as a cartoonist. BATMAN’S BATTLES: POST-TRAUMATIC PLAY From the beginning, horror was an

important element of Batman. Kane envisioned the character as “a lone, mysterious, grim vigilante who operated outside the law.” He succeeded in actualizing this vision. According to _The

World Encyclopedia of Comics_: > The Batman was portrayed as a relentless manhunter dedicated to the > eradication of crime. He would play on criminals’ fear of the > night and

exploit his bat-like appearance. He could be vicious—he > shot more than one man—and his amazing abilities overwhelmed the > common hoodlum. In short, The Batman was an avenging

vigilante. He > was never depicted as the bon vivant, talk-of-the-party > crimefighter; rather, the early Batman strips presented him as a > slightly unsavory character. This dark,

mysterious mood was greatly > cultivated and well-portrayed in the 1940s and early 1950s. After discussing how the mood of the comic strip lightened up in the second year of publication,

Kane wrote, “I prefer the first year of Batman when he operated solo and was a more sombre [sic] character.” He also refers to this Batman as looking “vampirish” and “ominous-looking,” the

same adjective he used to describe that dark night in the lumberyard. But how might Batman be linked to that night? First we need to establish that the attack by the Vultures created a

psychic trauma. In common with other trauma victims, Kane is fascinated with the dark side of life. More significant, Kane wrote that the assault in the lumberyard remains etched in his

memory like a nightmare. His vivid blow-by-blow account of the assault, some 57 years later, is exactly the sort of detailed memory that plagues people who have suffered a traumatic

experience. I believe Kane was traumatized, and used his art to symbolically reenact his trauma. He acknowledged that Bruce Wayne and Batman were his alter egos. When consulted on the script

of the movie “Batman,” Kane advised that, “Bruce Wayne should be played as a psychologically disturbed eccentric who is not quite focused except when he dons his bat-regalia to fight

crime.” Then he admitted, “I drew Bruce Wayne in my own image.” Batman provided Kane with the opportunity, in fantasy, to take revenge repeatedly—and for the entire span of his career—on the

hoodlums of the world. Instead of the defeated, helpless, terrorized victim Kane felt that night in the lumberyard, Batman is the master who strikes terror in others. “Zorro” was not

sufficient to defeat the Vultures, but Batman would have no problem. Batman not only reenacts Kane’s trauma by repeatedly fighting bad guys; he does so in a manner inspired by Kane’s night

in the lumberyard. Just as Kane used a grappling hook to ward off his attackers, one of Batman’s earliest and most frequently used weapons is a grappling hook. As I mentioned before, trauma

scholars describe post-traumatic play as having three qualities: It is long-lasting, repetitive, and grim. Here we have 75 years of exploits in more than 4000 comic books, which certainly

qualifies as long-lasting and repetitive. As for grim, consider this admission by Kane: “Had my early humorous strips been as successful as ‘Batman,’ I would have stayed with that style

because, frankly, I received more pleasure from drawing them than I ever did from drawing ‘Batman.’” Even when Kane intended to create what he called a “gag strip” a year before the birth of

Batman, he could not fully avoid what appear to be the echoes of trauma. Published in Circus Comics, the strip was called _Sidestreets of New York_ and featured a mild-mannered boy who is

accosted by the Gas House Gang and pushed into the river with his clothes on. In reminiscing about the attack by the Vultures, Kane displayed another common symptom of trauma victims—finding

reasons why he should have known in advance about the danger or suspected that something bad would occur. Psychologists refer to this as _omen formation_. Here’s how Kane took

responsibility for his encounter with the Vultures: “I must confess that taking up the violin was a drastic mistake that almost altered my life. ... I should have known better than to be

seen carrying a violin through the rough neighborhoods of the Bronx.” So, according to Kane, the beating he suffered was not because he had the ill fortune to be accosted by a gang of

hoodlums. It was something he could have predicted. It was in his control all the time. He simply made a mistake. He chose the wrong instrument. This explanation, I believe, is Kane’s

defense against the terror of being helpless. POST-TRAUMATIC RESONANCE: THE DARK KNIGHT RETURNS Of course, we can only speculate about whether Kane’s life-threatening encounter with the

Vultures on a dark night in a Bronx lumberyard inspired his creation of Batman. But regardless, the Batman myth, as originally conceived and as elaborated in contemporary interpretations,

leaves no doubt that Bruce Wayne’s trauma is the raison d’être and driving force behind his life’s drama—or the reason why he endures. As of this month, Batman has entertained fans for the

past 75 years. He is now the only comic book superhero who has remained continuously in print since the Golden Age of comics, outlasting even his most famous colleague, Superman, who

disappeared in 1992 but was then resurrected. There are many reasons for Batman’s popularity. Here I want to focus only on the role of trauma in his enduring appeal. I am particularly

interested in the talented children who were so drawn to Batman that they grew up to become the writers and illustrators who inherited the character and now perpetuate the legend. Which

aspects of Batman lore do they perpetuate? Often, it’s the dark effects of his traumatic origins. After a period of encounters with spacemen and silly characters, culminating in the camp

comic Batman many still remember from the ‘60s TV show, the early 1970s saw the lifting of rigid restrictions on comic-book content. Liberated from those restraints, the Batman legend was

free to evolve in whichever direction best expressed what psychoanalyst Jacob Arlow called “the communal myth.” What has evolved—and what we can take as the essential myth of Batman—is true

to Kane’s original conception: Batman as a dark, foreboding, brooding, obsessed victim. Batman’s return to his Dark Knight roots was led by writer and editor Dennis O’Neil. He envisioned

Batman as a Darknight Detective “whose parents were killed by a thief in the night in front of his eyes, and who grew up with a kind of schizoid paranoia that made him believe it was his

role in life to track down—at times even maim—the villains of the world.” Batman editor Robert Greenberger noted: “Superman has always been a light, positive hero, Batman has been grim and

possessed.” Batman’s world matches his mood. “Not the sunny place most superheroes are accustomed to,” observed Vaz. “Batman’s world is a place where capricious fate can deal out sudden

death to innocents.” It is, according to Vaz, a world that emulates a particular genre in literature and film: > The word noir ... has come to stand for a dark, fatal vision ... . >

Even when the hero of a noir piece emerges triumphant, some price, > usually the early loss of a loved one, has been paid. The Batman > mythos has been steeped in such noir traditions

from the very > beginning. ... This noir menace is the glue that holds the whole of > the Batman oeuvre together. ... Despite the risks and the air of > menace (perhaps because of

them), fans for fifty years have been > plunging into the darkness with the Batman. Vaz’s parenthetical guess is right on the mark: It is precisely the air of menace that draws readers to

Batman. In his essay, “Why I Chose Batman,” Stephen King elaborated the theme of Batman as a scary figure. After discussing how Superman’s superpowers, including the ability to fly, made it

difficult to identify with him, the author wrote: > Maybe the real reason that Batman appealed to me more than the other > guy. > > There was something sinister about him. >

> That’s right. You heard me. > > Sinister. > > ... Batman was a creature of the night. ... > > In those Batman-busts-in panels, you almost always saw a horrid >

species of fear on the faces of the hoods he was about to flush down > the toilet ... Yeah, I thought ... that’s right, they should look > scared, I’d sure be scared if something like

that busted in on me. > I’d be scared even if I wasn’t doing something wrong. Another reader who thought the illustrations looked scary was an eight-year-old boy named Frank, who was

destined to play a major role in shaping the Batman myth. Frank Miller’s 1986 graphic novella, _The Dark Knight Returns_, is generally credited with creating a resurgence of interest in

Batman; newspapers and magazines heralded its release as the coming of age for comic books. Here is Miller’s vision of Batman: “Do you know who I am, punk? I’m the worst nightmare you ever

had. Kind that made you wake up screaming for your mother.” This is the sort of terror that occupies the world of Stephen King, who praised Frank Miller’s vision as “the finest piece of

comic art ever to be published in a popular edition.” Contemporary interpretations of Batman repeatedly emphasize Bruce Wayne’s trauma. Vaz believes, “This hero called the Dark Knight would

probably have a very different place in comics history if not for that brutal origin, the memories of which are always lurking in the shadows of his mind and in the background of the mythos.

... It’s what haunts him, drives him, makes him the hero he is.” In _Batman: Year One_, another Frank Miller story, Bruce Wayne describes the trauma as the night “all sense left my life.”

This is the changed attitude about life that is a hallmark of traumatized children. That attitude is evident whenever Batman’s thoughts turn to the tragic event that occurred in what has

become known as “Crime Alley.” Batman has other symptoms of psychic trauma. A 1989 story, “Blind Justice,” written by Sam Hamm, depicts Batman as being plagued by anguish, nightmares, and

wracking guilt. Hamm, who also wrote the screenplay to the 1989 Batman film, recalled Batman as being “very dark and ominous and quirky. That really makes the strongest impression on you

when you’re a kid. ... Batman is a mysterious guy; he’s essentially a vigilante, and he’s a fairly disturbed character. His whole gimmick is, he wants to be menacing, he wants to be

frightening, he wants to be shadowy.” Roger Ebert had trouble with this “gimmick” as portrayed in the 1989 movie _Batman_: “There was something off-putting about the anger beneath the

movie’s violence,” he wrote. “This is a hostile, mean-spirited movie about ugly, evil people, and it doesn’t generate the liberating euphoria of the ‘Superman’ or ‘Indiana Jones’ pictures.

It’s rated PG-13, but it’s not for kids.” Recall that post-traumatic play is grim. Ebert recognized this quality and for him it was the obvious drawback of the movie—a movie that Bob Kane

said kept him “spellbound.” In a critique that strikes at the heart of the film’s resonance with Kane’s traumatic vision, Ebert complained: “The movie's problem is that no one seemed to

have any fun watching it. It’s a depressing experience. Is the opposite of comic book ‘tragic book’?” Let me offer one final example of post-traumatic resonance. The essence of psychic

trauma is the experience of a sudden, unexpected turn of events—the rug being pulled out from under, plunging the victim into a nightmare that remains etched in memory. A 1989 elaboration of

the origin of Batman captures this aspect of trauma with a simple metaphor. At some unspecified time before the murder of his parents, young Bruce fell into a hole, an old cave, filled with

bats. The experienced was terrifying. Reminiscing about this earlier trauma Batman thinks, “You're walking along and you fall through a hole. You never stop falling.” This, of course,

is exactly what it means to be traumatized. Thus the stage is set for Bruce Wayne’s identification with the bat as his means of mastering trauma. Approximately 20 years later, when the

re-traumatized orphan Wayne ponders the choice of his secret identity, he sees the bat and the curtain rises on his transformation to a “weird figure of the night.” This story closes as it

opened, with Batman perched, above the city, atop a stone sculpture protruding from the ridge of a skyscraper—a sculpture of a vulture. The final caption reads, “He breathes deeply, filling

himself with the night—and steps forward and falls—as he fell when he was a child—as he will fall for the rest of his life.” ABOUT THE AUTHOR Richard A. Warshak Richard A. Warshak is a

clinical professor of psychiatry at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center. He is the author of _Divorce Poison: How To Protect Your Family From Bad-mouthing and Brainwashing._