Play all audios:

THE CORNEA Light reflects off the object we’re looking at and enters the eye through the cornea, a clear, thin, dome-shaped tissue at the very front of the eye. The cornea has a curvature to

it and covers the eye, kind of like a crystal covering the face of a watch. “When rays of light enter the eye, they’re sort of parallel to each other,” says Rosen. “But as they pass through

the cornea, they bend and start to converge.” From there, light travels through a clear fluid, called the aqueous humor, which fills small chambers behind the cornea, nourishes the eye and

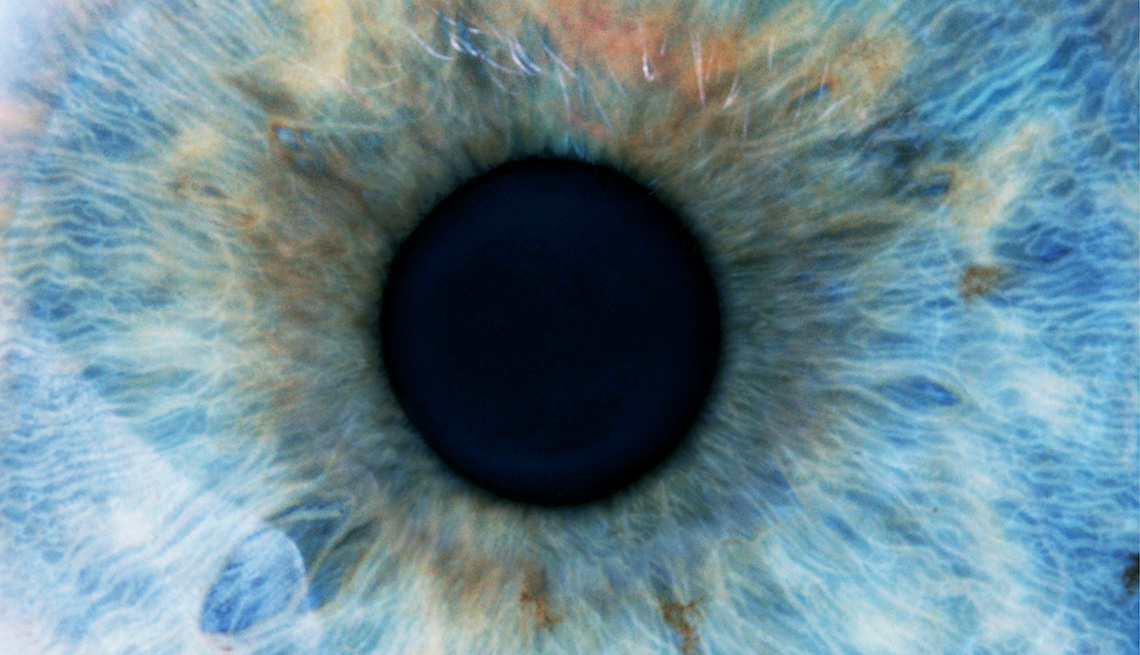

helps retain pressure to help the eye retain its shape. THE PUPIL AND IRIS As the light continues, it passes through an opening called the pupil, that black dot at the center of the eye. The

pupil is surrounded by the iris, the colored part of the eye. It’s the iris’s job to control how much light the pupil lets into the eye. When there is bright light, the iris uses muscles to

change the size of the pupil, making it narrow to let in less light (constriction) or wider to let in more light (dilation). AARP/Shutterstock THE LENS Next, the light penetrates the lens,

a transparent structure that works with the cornea to bend light and focus it onto the retina, which is located in the back of the eye. “The lens accumulates proteins as we age, causing a

cloudy lens, or cataracts,” says Jaclyn Haugsdal, M.D., clinical assistant professor of ophthalmology and visual sciences at the University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine. Small elastic

muscles, known as ciliary muscles, which are attached to the lens, help it change its shape in order to focus at various distances. When these muscles contract, the curvature of the lens

increases, allowing us to see objects that are close up. When these muscles relax, the lens becomes flattened, helping with long-range vision. THE VITREOUS HUMOR The large space behind the

lens, in the back portion of the eye and in front of the retina, is filled with a clear, gel-like substance, called the vitreous humor, that attaches to the retina at several points. The gel

helps keep the space in the middle of the eye clear so light can reach the retina. “It also provides some elasticity to the eye, helping it keep its shape,” says Rosen. “For example,

rubbing your eyes causes your eye pressure to spike, but it returns to normal when you stop rubbing. Or, if you poke your eye, it doesn’t automatically deflate because this kind of elastic

material fills the eye and absorbs the impact, preventing it from causing much damage.” THE RETINA From there, the light hits the retina, a thin, light-sensitive layer of tissue lining in

the back wall of the eye. (Interesting tidbit: The curvature of the lens and bending of light actually creates an upside-down image on the retina. The brain eventually turns the image right

side up.) Embedded in the retina are millions of light-sensitive cells, called photoreceptors. There are two types: cones and rods. Cones are responsible for producing the visual sharpness

of the eye — seeing road signs when driving, fine print when reading or recognizing facial details like the color of someone’s eyes — as well as color vision. “Most of these cones are

concentrated in a very specific area in the center of retina, called the macula,” says Haugsdal. The rods are located mostly in the outer edges of the retina. They are more sensitive to

lower light levels and help us with night vision, allowing us to see in a dimly lit room, for example. “The marvelous thing about our eyes is that they have incredible dynamic range that

allow them to adjust to a huge differential in terms of light,” says Rosen. “You can see in almost pitch darkness, but you can also see in bright sunlight. A camera doesn’t have that range.

You reach levels of light where it’s either too dark or too light to get a good picture.” These cells work together in the retina to detect and absorb the light rays, then convert it into

electrical signals, which are then sent to the visual cortex in the back of the brain, via the optic nerve in the back of the eye. The brain interprets these impulses, turning the signals

into the images that we see. THE BRAIN Almost half of our brain capacity is devoted to processing visual information, according to researchers at MIT. In fact, when it comes to vision, our

brain — and its ability to process those points of light — is every bit as important as the baby browns, blues and greens that we’re peering through. Ultimately, “it’s where the information

is assembled,” Rosen says. “We see with our brain.”