Play all audios:

ABSTRACT We used Cox regression analyses to assess mortality outcomes in a combined cohort of 7675 women who received diethylstilbestrol (DES) through clinical trial participation or

prenatal care. In the combined cohort, the RR for DES in relation to all-cause mortality was 1.06 (95% CI=0.98–1.16), and 1.11 (95% CI=1.02–1.21) after adjusting for covariates and omitting

breast cancer deaths. The RR was 1.07 (95% CI=0.94–1.23) for overall cancer mortality, and remained similar after adjusting for covariates and omitting breast cancer deaths. The RR was 1.27

(95% CI=0.96–1.69) for DES and breast cancer, and 1.38 (95% CI=1.03–1.85) after covariate adjustment. The RR was 1.82 in trial participants and 1.12 in the prenatal care cohort, but the

DES–cohort interaction was not significant (_P_=0.15). Diethylstilbestrol did not increase mortality from gynaecologic cancers. In summary, diethylstilbestrol was associated with a slight

but significant increase in all-cause mortality, but was not significantly associated with overall cancer or gynaecological cancer mortality. The association with breast cancer mortality was

more evident in trial participants, who received high DES doses. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS ASSOCIATIONS OF PER- AND POLYFLUOROALKYL SUBSTANCES WITH UTERINE LEIOMYOMATA

INCIDENCE AND GROWTH: A PROSPECTIVE ULTRASOUND STUDY Article 24 June 2024 EXPOSURE TO PERFLUOROALKYL SUBSTANCES IN EARLY PREGNANCY AND RISK OF SPORADIC FIRST TRIMESTER MISCARRIAGE Article

Open access 11 February 2021 REPRODUCTIVE AND ENVIRONMENTAL EXPOSURES AND THE BREAST CANCER RISK IN TAIWANESE WOMEN Article Open access 02 August 2021 MAIN Starting in about 1940,

diethylstilbestrol (DES), a powerful nonsteroidal oestrogen, was used to prevent pregnancy loss and complications. Although clinical trials conducted in the 1950s showed DES was not

effective (Dieckmann et al, 1953; Swyer and Law, 1954), use continued for another two decades. Diethylstilbestrol was withdrawn from use during pregnancy in the early 1970s, after it was

shown that _in utero_ exposure was strongly associated with the risk of vaginal adenocarcinoma (Herbst et al, 1971). Until that time, as many as 2 million women in the US (Noller and Fish,

1974), and 4 million women worldwide (Newbold, 1993) were given DES during pregnancy. Most studies, but not all (Vessey et al, 1983), have suggested a positive association between DES taken

during pregnancy and breast cancer incidence (Bibbo et al, 1978; Clark and Portier, 1979; Beral and Colwell, 1980; Greenberg et al, 1984; Hadjimichael et al, 1984; Colton et al, 1993;

Titus-Ernstoff et al, 2001), although the latter four studies produced findings compatible with chance. Of the studies assessing DES in relation to breast cancer mortality, one observed a

significant association (Calle et al, 1996); four produced suggestive findings that were not of statistical significance (Bibbo et al, 1978; Clark and Portier, 1979; Hadjimichael et al,

1984; Colton et al, 1993); and another found no association (Greenberg et al, 1984). To date, only one study formally assessed all-cause or disease-specific mortality outcomes, and found

little evidence of an association with DES (Greenberg et al, 1984). In the present paper, we present findings based on the largest study to date of mortality outcomes in women with

documented DES exposure. MATERIALS AND METHODS We assessed exposure to DES during pregnancy in relation to cause-specific and total mortality, with a particular interest in gynaecological

cancers, and those known to be influenced by exposure to exogenous oestrogen. The analyses were based on a combined cohort, the design and methods of which have been described previously

(Titus-Ernstoff et al, 2001). The combined cohort consists of DES-exposed and unexposed women from two previous follow-up studies, the Women's Health Study (WHS) and the Dieckmann

Study, both of which assessed the long-term health consequences of DES exposure during pregnancy. The WHS enrolled DES-exposed and unexposed women who were ascertained through a

retrospective review of obstetrics records for the period 1940–1960 at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, MN; Mary Hitchcock Memorial Hospital in Hanover, NH; a pregnancy clinic at the Boston

Lying-In Hospital, in Boston, MA; and a private obstetrics practice in Portland, ME (Greenberg et al, 1984; Colton et al, 1993; Titus-Ernstoff et al, 2001). Diethylstilbestrol-exposed women

were those whose records indicated that DES (or, rarely, another nonsteroidal oestrogen) had been prescribed during at least one pregnancy resulting in a live birth. The date of the first

DES-exposed live birth was the study entry date; unexposed women were matched within ±2 years to the DES-exposed women's birth dates, and were assigned the same date of study entry as

the exposed woman to whom they were matched. Active follow-up of the WHS cohort was implemented in the early 1980s and continued intermittently through 1989. The second cohort consists of

women who participated in the Dieckmann Study, a placebo-controlled clinical trial of the effects of DES on pregnancy losses. The trial was conducted in the early 1950s at the University of

Chicago, and enrolled women who were 6–20 weeks pregnant. The cumulative dose of DES tested was 11–12 g. For these women, the date of pregnancy outcome was the study entry date. Participants

were re-contacted for follow-up in 1976. In both the WHS and the Dieckmann cohorts, DES exposure (or lack thereof) was documented in the medical record, the occurrence of cancer was

confirmed by medical record, and cause of death was verified by death certificate. Follow-up of the combined cohort was implemented by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) in 1992, at which

time intense tracing efforts were used to locate the women who previously participated in the WHS and Dieckmann studies. In conjunction with the 1994 data collection phase, we obtained

either a questionnaire (including proxy questionnaires) or a death certificate for 6495 (84%) of the 7758 women initially ascertained for the WHS and Dieckmann studies. Deaths occurring

through the 1994 data collection phase were ascertained by death certificate; subsequently, mortality and cause of death were ascertained through the National Death Index. For a subset of

the WHS women (those initially ascertained through the Mayo Clinic), the underlying cause of death was determined through the Social Security Death Index. Follow-up through both sources

continued through 1 January 2000. For the present analysis, the outcomes were all-cause mortality, cause-specific mortality, including overall cancer death, and cause-specific cancer death.

Diseases were classified by trained nosologists according to the International Classification of Diseases (ICD), using both ICD-9 (Hart, 2000) and ICD-10 (WHO, 2003). Outcomes represented by

fewer than 10 events were classified as ‘other’, except when the outcome was potentially relevant to DES exposure (i.e., vulvar/vaginal and other gynaecologic cancers). The analyses are

based on 7675 of the 7758 women from the original cohorts (83 women were omitted owing to lack of information on study entry date). Covariate information was available for 7062 (92%) women,

based predominantly on the 1994 questionnaire responses, or on earlier questionnaire responses when necessary. Cox proportional hazards models (Cox, 1972), with time since study entry as the

timescale, were used to estimate mortality rate ratios associated with DES exposure. The women contributed person-time from the date of study entry until the date of death, or 1 January

2000, whichever occurred first. For the outcomes of ovarian, uterine, and cervical cancer, separate analyses censored follow-up at the date of hysterectomy. In general, the analyses were

conducted in the combined cohorts; in the presence of interaction between DES and cohort, the outcomes are reported separately for the WHS and Dieckmann cohorts. To assess departure from the

proportional hazards assumption, we assessed log–log survival plots and formally tested interaction terms between DES and time (since study entry) in relation to the study outcomes. Year of

birth and study entry year were covariates in all models. Additional covariates, including education (in years; 0–8, 9–12, 13–16, ⩾17), smoking (ever, never), and body mass index (BMI) (kg

m−2) (⩽21, 21–23, 24–27, ⩾28) were considered when available and appropriate for specific mortality outcomes. Breast cancer models contained terms for family history of breast cancer, BMI,

age at first pregnancy (<20, 20–24, 25–29, 30–39, ⩾40), and parity (1–2, 3–4, ⩾5); ovarian cancer analyses were adjusted for parity. We found no evidence of confounding by these variables

or by cohort (RR estimates changed less than 10%); consequently, the RR shown in the tables are adjusted for birth year and study entry year. Missing covariate data were included in models

by use of indicator variables. RESULTS Table 1 shows the current status of the 7675 women on whom our analyses are based. Of these, 2237 (29.1%) (1156 exposed, 1081 unexposed) were known to

have died and cause of death was determined for 2193 (98.0%) (1128 exposed, 1065 unexposed). Exposed and unexposed women in the combined cohort were of comparable age at study entry.

Education, BMI, parity, and smoking history, when available, were similar for the exposed and unexposed (Table 2). In the combined cohort, the RR for DES in relation to all-cause mortality

was 1.06 (95% CI=0.98–1.16) (Table 3). When breast cancer deaths were not counted as outcomes, the RR was 1.05 (95% CI=0.96–1.14) in the combined cohort, 1.03 (95% CI=0.94–1.13) in WHS, and

1.12 (95% CI=0.91–1.39) in the Dieckmann cohort. After additional adjustment for BMI and smoking, and with breast cancer omitted, the RR was 1.11 (95% CI=1.02–1.21) in the combined cohort;

the findings were identical for the individual cohorts. The combined grouping of cerebrocardiovascular disease accounted for about one-third (33.8%) of all deaths, but there was little

evidence that DES increased overall cerebrocardiovascular mortality or mortality from cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, or other vascular conditions. The slightly elevated RR for DES in

relation to mortality owing to infectious disease, neuropsychiatric conditions, Alzheimer's disease, digestive diseases, and diabetes were compatible with chance. A moderately strong

and statistically significant association was observed between DES exposure and deaths owing to kidney/urinary tract disease (RR=2.39; 95% CI=1.14–4.99), and the RR was 2.57 (95%

CI=1.23–5.39) after further adjustment for smoking. Mortality from violence/accident was similar for the exposed and unexposed women. There was little evidence of an association between DES

and noncancer mortality classified as ‘other’; RR=0.90 (95% CI=0.62–1.29). Inverse associations were observed for pulmonary and liver disease mortality in relation to DES exposure, but were

consistent with chance, and the results were similar after adjustment for smoking (data not shown). Overall, 37.7% of deaths were owing to cancer (Table 3). In the combined cohort, the RR

for overall cancer mortality was 1.07 (95% CI=0.94–1.23). In analyses that omitted the breast cancer outcomes, the RR was 1.02 (95% CI=0.88–1.19) in the combined cohort, 0.96 (95%

CI=0.81–1.14) in the WHS, and 1.37 (95% CI=0.94–2.00) in the Dieckmann cohort. The interaction between DES exposure and cohort in relation to overall cancer mortality was not statistically

significant (_P_=0.11). After further adjustment for BMI and smoking, and with breast cancer deaths omitted, the RR for overall cancer mortality was 1.09 (95% CI=0.94–1.28) in the combined

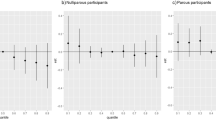

cohort, 1.06 (95% CI=0.90–1.26) in WHS, and 1.35 (95% CI=0.92–1.97) in the Dieckmann cohort. In the combined cohort, the RR was 1.27 (95% CI=0.96–1.69) for the association between DES and

breast cancer death; after further adjustment for family history of breast cancer, BMI, age at first pregnancy, and parity, the RR was 1.38 (95% CI=1.03–1.85). The RR was 1.12 (95%

CI=0.80–1.55) in the WHS cohort and 1.82 (95%=1.04–3.18) in the Dieckmann cohort, but the interaction between DES and cohort in relation to breast cancer mortality was not statistically

significant (_P_=0.15). The association with breast cancer mortality did not change over time; the RR was 1.31 and 1.25, respectively, for less than 30 years, and 30 or more years since

exposure. Diethylstilbestrol was not associated with an increased risk of death due to ovarian cancer (RR=0.87; 95% CI=0.51–1.46); the RR was essentially the same after adjustment for

parity, and when follow-up was censored at hysterectomy. The RR were 1.48 (95% CI=0.53–4.17) and 0.25 (95% CI=0.05–1.18), respectively, for the associations with uterine and cervical cancer

mortality, and both RR were materially unchanged after adjustment for smoking and when follow-up was censored at hysterectomy. There was no association with vulvar/vaginal cancer (RR=1.00;

95% CI=0.20–4.93). The RR suggested elevated risk of death from lung, urinary, and head and neck cancer, as well as non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, melanoma, and leukaemia, but confidence

intervals were wide and included the null value. Further adjustment for smoking did not materially change the RR of the cancers known to be associated with that exposure. The inverse

associations suggested for brain cancer, cancer of the upper GI tract, and ‘other’ cancer were also imprecise. The inverse association with death from multiple myeloma was statistically

significant, RR=0.18 (95% CI=0.04–0.82), and was unchanged after adjustment for smoking. The data provided no evidence that DES was related to death from colorectal or other GI cancers.

DISCUSSION Our results are based on the largest mortality study to date of women with documented exposure to DES during pregnancy, with over 2000 deaths, of which 800 were from cancer and

nearly 200 from breast cancer. Our data suggest that DES is associated with a small elevation of all-cause mortality. The finding may reflect residual confounding by a lifestyle correlate,

although the RR was somewhat greater in the Dieckmann cohort, which consists of women who were enrolled in a clinical trial of DES and who received high doses of DES. There was no increase

of cerebrocardiovascular deaths, and the suggested increased risk of vascular deaths was consistent with chance. Clinical trial results from the Women's Health Initiative (WHI) suggest

increased risks of cerebrocardiovascular events, including stroke and thromboembolic events, in postmenopausal women using equine oestrogens, but the effects may be limited to current or

recent use (Women's Health Initiative, 2004). Also, WHI participants were 50–70 years of age at enrolment, whereas women in our study were in their childbearing years at the time of DES

use and at lower risk of cerebrocardiovascular outcomes. Current use of menopausal oestrogen may also increase risk of cognitive impairment (Shumaker et al, 2004), but our data showed no

association with mortality from psychiatric disease or Alzheimer's disease. Although the data indicated a moderately elevated mortality for kidney/urinary disease and an inverse

association with ‘other’ noncancer mortality, both of which were statistically significant, we assessed a large number of outcomes, and these findings may represent false positives. We are

unaware of human evidence linking DES to kidney/urinary disease, although DES-induced structural and functional changes in the renal tissue of rats have been reported (Onarglioglu et al,

1998). The increased risk of breast cancer death observed in the combined cohort is consistent with the large follow-up study of DES in relation breast cancer mortality (Calle et al, 1996)

and with our previous findings (Titus-Ernstoff et al, 2001). An early analysis of the Dieckmann data suggested a moderately strong association with breast cancer mortality (RR=2.89; 95%

CI=0.99–8.47) (Clark and Portier, 1979), and our finding in the combined cohort was largely owing to the elevated mortality in the Dieckmann group. The association with breast cancer

mortality in the Dieckmann cohort is noteworthy because, unlike the WHS, DES exposure was in a clinical trial, and was not owing to a history of pregnancy complications, indicating an

aberrant hormonal milieu or specialised obstetrics care, which might be correlated with lifestyle characteristics. Women participating in the Dieckmann trial received especially high doses

of DES resulting in a cumulative dose of 11–12 g over the course of the pregnancy. Based on studies involving women treated during obstetrics care (Hadjimichael et al, 1984), doses given to

pregnant women in the WHS were probably much lower (about 1.1 g cumulative). Possibly, the stronger association between DES and breast cancer mortality observed in the Dieckmann study

reflects the higher doses of DES administered to women in that cohort and/or the clinical trial design, which should eliminate confounding. However, a study examining dose in relation to

breast cancer risk found no evidence of dose response (Hadjimichael et al, 1984), and our previous study of breast cancer incidence in the combined cohort showed similar risks for WHS and

Dieckmann women (Titus-Ernstoff et al, 2001). Some studies of breast cancer incidence, including two previous studies based on the WHS and Dieckmann cohorts, suggested possible latency

effects (Bibbo et al, 1978; Colton et al, 1993), but others did not (Greenberg et al, 1984; Hadjimichael et al, 1984; Titus-Ernstoff et al, 2001), including a large study conducted in

Connecticut (Hadjimichael et al, 1984). Consistent with previous reports (Hadjimichael et al, 1984; Calle et al, 1996), we found no evidence that breast cancer mortality differed according

to time since exposure. Although findings in the Dieckmann cohort suggested a small increased risk of overall cancer mortality, even after removing breast cancer deaths, the results were

consistent with chance, as were the findings for the combined cohort. We also found little evidence that DES was associated with specific cancers other than breast cancer. Previous studies

of endometrial cancer and DES during pregnancy or as hormone therapy have produced conflicting results; one study suggested a decreased risk (Hadjimichael et al, 1984), whereas others showed

an increased risk (Hoover et al, 1976; Autunes et al, 1979). In our data, the modestly elevated mortality rate ratio for uterine cancer was compatible with chance. We also found no evidence

that DES exposure was associated with ovarian or cervical cancer. Others have suggested increased risk of ovarian (Hoover et al, 1977; Hadjimichael et al, 1984) and possibly cervical cancer

(Hadjimichael et al, 1984), but case numbers were small. We also found no indication that DES use during pregnancy was associated with vaginal/vulvar cancers, tumours that occur in women

exposed to DES _in utero_ (Herbst et al, 1971). We have no explanation for the strong inverse association with multiple myeloma, but we assessed numerous outcomes, and the finding may be a

false positive. The size of the combined cohort, the large number of outcomes, and the documented use of DES are strengths of our study. Diethylstilbestrol doses are known for the Dieckmann

women, most of whom received a high cumulative dose, but are unknown for the WHS participants, precluding assessment of risk according to dose. Although we had limited information on

potential confounders, some data were available for major health indicators such as BMI and smoking, and breast cancer risk factors were available for most women. The possibility of

incomplete mortality ascertainment is a limitation of all studies relying on NDI searches. Similar proportions of the exposed or unexposed women in the initial cohort were lost to follow-up

as of the 1994 data collection phase (6.8% exposed, 9.3% unexposed), and cause of death was ascertained for 97.6% of the exposed and 98.5% of unexposed decedents. Although incomplete

ascertainment may have attenuated some associations, it seems unlikely that ascertainment would be associated with DES exposure; so our results should not be biased away from the null. In

summary, our findings indicate that women given DES during pregnancy experienced a slight but statistically significant elevation in all-cause mortality after adjusting for covariates and

omitting breast cancer deaths. Our data did not show an elevated risk of mortality from cancer overall or from gynaecological cancers. However, an increased risk of breast cancer mortality

was evident, particularly in the Dieckmann women, who received high doses of DES during pregnancy. CHANGE HISTORY * _ 16 NOVEMBER 2011 This paper was modified 12 months after initial

publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication _ REFERENCES * Autunes CMF, Stolley PD, Rosenshein NB, Davies JL, Tonascia JA, Brown C, Burnett L, Rutledge

A, Pokempner M, Garcia R (1979) Endometrial cancer and estrogen use. Report of a large case-control study. _N Engl J Med_ 300: 9–13 Article Google Scholar * Beral V, Colwell L (1980)

Randomised trial of high doses of stilboestrol and ethisterone in pregnancy: long term follow-up of mothers. _BMJ_ 281: 1098–1101 Article CAS Google Scholar * Bibbo M, Haenszel WM, Wied

GL, Hubby M, Herbst AL (1978) A twenty-five-year follow-up study of women exposed to diethylstilbestrol during pregnancy. _N Engl J Med_ 298: 763–767 Article CAS Google Scholar * Calle

EE, Mervis CA, Thun MJ, Rodriguez C, Wingo PA, Heath Jr CW (1996) Diethylstilbestrol and risk of fatal breast cancer in a prospective cohort of US women. _Am J Epidemiol_ 144: 645–652

Article CAS Google Scholar * Clark LG, Portier KM (1979) Diethylstilbestrol and the risk of cancer. _N Engl J Med (ltr)_ 300: 263–264 Article CAS Google Scholar * Colton T, Greenberg

ER, Noller K, Resseguie L, Van Bennekom C, Heeren T, Zhang Y (1993) Breast cancer in mothers prescribed diethylstilbestrol in pregnancy. _J Am Med Assoc_ 269: 2096–2100 Article CAS Google

Scholar * Cox DR (1972) Regression models and life tables. _J R Stat Soc B_ 34: 187–220 Google Scholar * Dieckmann WJ, Davis ME, Rynkiewicz LM, Pottinger RE (1953) Does the administration

of diethylstilbestrol during pregnancy have therapeutic value? _Am J Obstet Gynecol_ 66: 1062–1081 Article CAS Google Scholar * Greenberg ER, Barnes AB, Resseguie L, Barrett JA, Burnside

S, Lanza LL, Neff RK, Stevens M, Young RH, Colton T (1984) Breast cancer in mothers given diethylstilbestrol in pregnancy. _N Engl J Med_ 311: 1393–1398 Article CAS Google Scholar *

Hadjimichael OC, Meigs JW, Falcier FW, Thompson WD, Flannery JT (1984) Cancer risk among women exposed to exogenous estrogens during pregnancy. _J Natl Cancer Inst_ 73: 831–834 CAS PubMed

Google Scholar * Hart AC (ed) (2000) _ICD-9 Code Book_. Reston, VA: St Anthony Publishing Google Scholar * Herbst AL, Ulfelder H, Poskanzer DC (1971) Adenocarcinoma of the vagina.

Association of maternal stilbestrol therapy with tumor appearance in young women. _N Engl J Med_ 284: 878–881 Article CAS Google Scholar * Hoover R, Fraumeni Jr JF, Everson R, Myers MH

(1976) Cancer of the uterine corpus after hormonal treatment for breast cancer. _Lancet_ 1: 885–887 Article CAS Google Scholar * Hoover R, Gray LA, Fraumeni Jr JF (1977) Stilboestrol

(Diethylstilbestrol) and the risk of ovarian cancer. _Lancet_ 2: 533–534 Article CAS Google Scholar * Newbold RR (1993) Gender-related behavior in women exposed prenatally to

diethylstilbestrol. _Environ Health Perspect_ 101: 208–213 Article CAS Google Scholar * Noller KL, Fish CR (1974) Diethylstylbestrol usage: its interesting past, important present, and

questionable future. _Med Clin N Am_ 58: 793–810 Article CAS Google Scholar * Onarglioglu B, Gunay Y, Goze I, Koptagel E (1998) Renal ultrastructural alterations following administration

of diethylstilbestrol. _Tr J Med Sci_ 28: 369–374 Google Scholar * Shumaker SA, Legault C, Kuller L, Rapp SR, Tal L, Lane DS, Fillit H, Stefanick ML, Hendrix SL, Lewis CE, Masaki K, Coker

LH (2004) Conjugated equine estrogens and incidence of probably dementia and mild cognitive impairment in postmenopausal women. _J Am Med Assoc_ 291: 2947–2958 Article CAS Google Scholar

* Swyer GIM, Law RG (1954) An evaluation of the prophylactic ante-natal use of stilboestrol. Preliminary report. _J Endocrinol_ 10: vi Google Scholar * Titus-Ernstoff L, Hatch EE, Hoover

RN, Palmer J, Greenberg ER, Ricker W, Kaufman R, Noller K, Herbst AL, Colton T, Hartge P (2001) Long-term cancer risk in women given diethylstilbestrol (DES) during pregnancy. _Br J Cancer_

84: 126–133 Article CAS Google Scholar * Vessey MP, Fairweather DV, Norman-Smith B, Buckley J (1983) A randomized double-blind controlled trial of the value of stilboestrol therapy in

pregnancy: long-term follow-up of mothers and their offspring. _Br J Obstet Gynecol_ 90: 1007–1017 Article CAS Google Scholar * Women's Health Initiative Steering Committee (2004)

Effects of conjugated equine estrogen in postmenopausal women with hysterectomy. _J Am Med Assoc_ 291: 1701–1712 * World Health Organization (2003) ICD-10 Code Book. International

Classification of Diseases. _US Natl Center Health Stat_ Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We thank the project coordinators at all participating study centres. We also thank Judy Harjes

and Shafika Abrahams-Gessel for their contributions to this study. This project was funded by the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, under contract numbers RFP NCI

33011-21, CP50531-21, and CP01012-21. AUTHOR INFORMATION AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Department of Community and Family Medicine, Dartmouth Medical School, and the Norris Cotton Cancer

Center, Lebanon, 03756, NH, USA L Titus-Ernstoff & R Troisi * Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, 20892, MD, USA R Troisi, P Hartge & R

N Hoover * Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Boston University School of Public Health, Boston, 02118, MA, USA E E Hatch * Slone Epidemiology Center, Boston University School of

Public Health, Boston, 02215, MA, USA J R Palmer & L A Wise * Information Management Services, Rockville, 20852, MD, USA W Ricker & M Hyer * Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology,

Methodist Hospital, Houston, 77030, TX, USA R Kaufman * Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, New England Medical Center, Boston, 02111, MA, USA K Noller & W Strohsnitter *

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Chicago, Chicago, 60637, IL, USA A L Herbst Authors * L Titus-Ernstoff View author publications You can also search for this author

inPubMed Google Scholar * R Troisi View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * E E Hatch View author publications You can also search for this

author inPubMed Google Scholar * J R Palmer View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * L A Wise View author publications You can also search for

this author inPubMed Google Scholar * W Ricker View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * M Hyer View author publications You can also search for

this author inPubMed Google Scholar * R Kaufman View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * K Noller View author publications You can also search

for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * W Strohsnitter View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * A L Herbst View author publications You can

also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * P Hartge View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * R N Hoover View author publications You

can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to L Titus-Ernstoff. RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS From twelve months after its original publication,

this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/ Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Titus-Ernstoff, L., Troisi, R., Hatch, E. _et al._ Mortality in women given

diethylstilbestrol during pregnancy. _Br J Cancer_ 95, 107–111 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6603221 Download citation * Received: 07 April 2006 * Revised: 02 May 2006 * Accepted:

15 May 2006 * Published: 20 June 2006 * Issue Date: 03 July 2006 * DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6603221 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to

read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing

initiative KEYWORDS * DES * oestrogens * breast cancer * mortality