Play all audios:

ABSTRACT Syntheses of carbonate chemistry spatial patterns are important for predicting ocean acidification impacts, but are lacking in coastal oceans. Here, we show that along the North

American Atlantic and Gulf coasts the meridional distributions of dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) and carbonate mineral saturation state (Ω) are controlled by partial equilibrium with the

atmosphere resulting in relatively low DIC and high Ω in warm southern waters and the opposite in cold northern waters. However, pH and the partial pressure of CO2 (_p_CO2) do not exhibit a

simple spatial pattern and are controlled by local physical and net biological processes which impede equilibrium with the atmosphere. Along the Pacific coast, upwelling brings subsurface

waters with low Ω and pH to the surface where net biological production works to raise their values. Different temperature sensitivities of carbonate properties and different timescales of

influencing processes lead to contrasting property distributions within and among margins. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS PELAGIC CALCIUM CARBONATE PRODUCTION AND SHALLOW DISSOLUTION

IN THE NORTH PACIFIC OCEAN Article Open access 20 February 2023 GLOBAL CARBONATE CHEMISTRY GRADIENTS REVEAL A NEGATIVE FEEDBACK ON OCEAN ALKALINITY ENHANCEMENT Article 12 February 2025

DYNAMIC REDOX AND NUTRIENT CYCLING RESPONSE TO CLIMATE FORCING IN THE MESOPROTEROZOIC OCEAN Article Open access 20 October 2023 INTRODUCTION Absorption of anthropogenic CO2 from the

atmosphere has acidified the ocean, as indicated by increases in sea surface _p_CO2 and hydrogen ion concentration ([H+]) and decreases in pH, carbonate ion concentration

([\({\mathrm{CO}}_3^{2 - }\)]), and calcium carbonate (CaCO3) mineral saturation state1,2,3,4,5. The latter is a ratio of the ionic product, [Ca2+][\({\mathrm{CO}}_3^{2 - }\)], to its

saturated value below which CaCO3 dissolution may occur (in this paper we only target the saturation state of aragonite, Ωarag, a mineral form that comprises the shells and hard parts of

corals, mollusks, and many other marine organisms). More than a decade of ocean acidification research has improved our understanding of the mechanisms controlling the global spatial

patterns and temporal variations of ocean carbonate chemistry5,6,7,8, and has begun to reveal how ocean chemistry (e.g., pH and Ωarag)9,10,11,12,13 and marine organisms14,15,16 are

responding to anthropogenic CO2 uptake. In coastal regions, much of the ocean acidification research has focused on examining how anthropogenic CO2-induced acidification is mitigated or

exacerbated by biological production (removing CO2) in surface waters and subsequent respiration (adding CO2) in subsurface waters as a result of natural nutrient enrichment or human-induced

coastal eutrophication17,18,19,20. Attention has also been given to the effects of biological community composition and community metabolism on the potential to buffer or exacerbate ocean

acidification21,22. There is, however, incomplete knowledge of large-scale patterns of carbonate chemistry and the mechanisms controlling its variability in coastal oceans, largely due to

limited observations and the added complication of dynamic regional or local processes that can be large in magnitude. Examples of local processes that influence surface water distributions

of _p_CO2, pH, total alkalinity (TA), dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC), and Ωarag in ocean margins include river and wetland inputs, coastal circulation, vertical and lateral mixing, spatial

and seasonal temperature variations, the balance of biological production and respiration, and anthropogenic CO2 uptake23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30. Rivers usually carry more acidified waters

with a higher DIC/TA ratio than seawater, which may weaken the ability of coastal seas to withstand anthropogenic CO2-induced acidification29,31. Freshwater input can also suppress Ωarag by

reducing [Ca2+]. However, increased nutrient input from rivers may lead to elevated biological CO2 removal or basification in surface waters32, whereas the respiration of this organic

material back to CO2 in bottom waters may enhance acidification at depth17. Additionally, coastal upwelling can bring low pH and low Ωarag waters to shallow, nearshore regions and put

coastal biological systems in stress27. Subsequent CO2 release to the atmosphere and biological production stimulated by the accompanying upwelled nutrients may increase pH and Ωarag33. In

addition to these driving processes, it is important to understand the influence of temperature on the spatial distributions of carbonate system properties. Coastal currents often bring

waters from warm (or cold) locations to cold (or warm) locations, resulting in chemical equilibrium shifts and air–sea gas exchange, both of which are sensitive to temperature change:

$${\mathrm{CO}}_{\mathrm{2gas}}\mathop{\longleftrightarrow}\limits^{{K_0}}{\mathrm{CO}}_{\mathrm{2aq}},$$ (1) $${\mathrm{CO}}_{\mathrm{2aq}} + {\mathrm{H}}_{2}{\mathrm{O}} +

{\mathrm{CO}}_3^{2 - }\mathop{\longleftrightarrow}\limits^{{K_1/K_2}}2{\mathrm{HCO}}_3^ - .$$ (2) Here _K_0 is the solubility constant, and _K_1/_K_2 is the ratio of the first and second

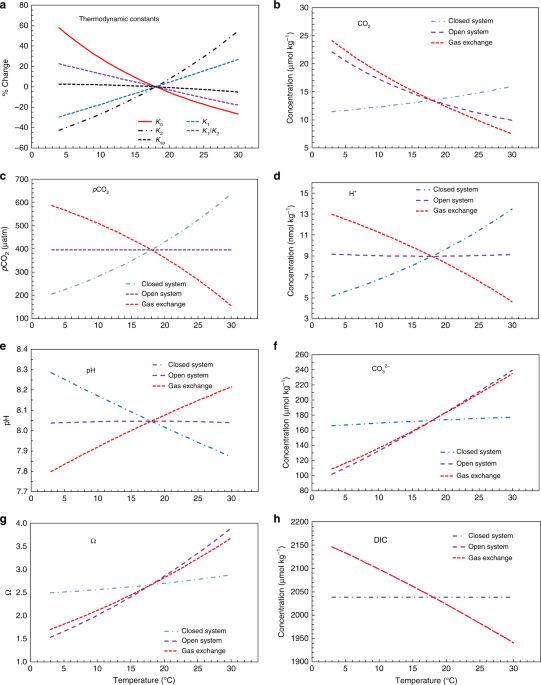

dissociation constants of carbonic acid. When a water mass isolated from the atmosphere (referred to herein as a closed system) is cooled, the ratio, _K_1/_K_2, will increase (Fig. 1a), and

the acid–base equilibrium will shift to the right to reduce dissolved CO2 (CO2aq) and \({\mathrm{CO}}_3^{2 - }\) and increase \({\mathrm{HCO}}_3^ -\) (Eq. 2). The gas solubility constant

will also increase, further reducing _p_CO2 following Henry’s Law (_p_CO2 = [CO2aq]/_K_0) (Fig. 1a–c), as gas exchange is not allowed to compensate the cooling process in a closed system

(Eq. 1). Although not explicitly shown in Eq. (2), cooling will also reduce [H+] and increase pH in a closed system because of the decrease in both acid dissociation constants (Fig. 1).

Importantly, cooling can shift a water mass from being a source of CO2 to the atmosphere in warm, subtropical waters to a sink for CO2 in cold, mid-latitude waters when gas exchange occurs

in an alongshore current. The process of cooling and gas exchange in an open-system increases CO2aq, a fraction of which combines with and reduces \({\mathrm{CO}}_3^{2 - }\) and thus Ωarag.

To illustrate the temperature dependences of the marine carbonate system, we define two thermodynamic end members: the closed system, with no gas exchange, and the open system, with a

complete CO2 gas exchange equilibrium between seawater and the atmosphere. Thus, our theoretical framework posits that the temperature-dependent change of a species or a property in an open

system is the combined effect of gas exchange caused by the solubility change and the subsequent internal thermodynamic equilibrium shift in a closed system (Fig. 1). Importantly, these two

temperature effects counteract each other for [CO2aq] (hereafter the subscript aq will be omitted), _p_CO2, [H+], and pH, whereas they work to enhance each other for [\({\mathrm{CO}}_3^{2 -

}\)] and [\({\mathrm{HCO}}_3^ -\)] (or roughly DIC), with atmospheric equilibration playing the dominant role in an open system (Fig. 1). In summary, the combined result of the thermodynamic

equilibrium shift and atmospheric equilibration during cooling is predicted to be an increase in [CO2] and DIC, essentially no change in [H+] and pH and, by definition, no change in _p_CO2,

and a relatively large decrease in [\({\mathrm{CO}}_3^{2 - }\)] and Ωarag in surface waters (Fig. 1)7,8,34,35,36. Therefore, spatial variations in pH and _p_CO2 largely reflect air–sea

disequilibrium caused by local physical and biological processes that act more rapidly than gas exchange. Here we report results from large-scale, regional marine carbonate chemistry

observing efforts on the Atlantic, Gulf, and Pacific coasts of North America. This synthesis reveals the domain-scale and local controls on carbonate properties driven by atmospheric CO2

exchange and physical, chemical, and biological ocean processes. Our comparative study of marine carbonate chemistry across physically and biologically dissimilar ocean margins provides new

insight about the mechanisms controlling CO2 parameter distributions, timescales of variability, and responses to ocean warming and acidification. RESULTS THE ATLANTIC AND GULF COASTS The

North American Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico (GOM) coastal regions are characterized by broad, shallow shelves influenced on the landward side by rivers and wetlands and on the seaward side by

alongshore currents. Most notably, the northbound Gulf Stream Current system brings warm, high-salinity source waters from the tropics, while the southbound Labrador Current brings cold,

low-salinity source waters from the Arctic and subarctic regions (Supplementary Fig. 1)37,38,39. While data presented here were collected during slightly different summer months on the

Atlantic coast (Supplementary Table 1), the spatial patterns of all parameters are consistent for the cruises conducted in 2007, 2012, and 2015, each plotted with a shift in longitude for

the purpose of illustration (Fig. 2, Supplementary Table 2). Sea surface temperature (SST) (Fig. 2a) and salinity (SSS) (Fig. 2b) decrease from southwest to northeast. The surface TA

distribution follows that of salinity, with the highest TA values in the GOM, a sharp south-to-north decrease along the Atlantic coast24,25, and nearshore modifications by major rivers40

(Fig. 2c). In contrast to the sharp meridional decline in TA, the DIC gradient is weak along the Atlantic coast, exhibiting smaller south-to-north decreases and some high values in the

northern regions (Fig. 2d). Thus, the DIC/TA ratio increases sharply from south-to-north (Fig. 2f), which strongly correlates with SST (Supplementary Table 3). The DIC/TA ratio is a measure

of the acid–base equilibrium point of seawater, with higher ratio indicating higher CO2 fraction in the DIC pool and more acidified, less buffered states41. Note, while the GOM has both high

DIC and TA values, its DIC/TA ratio is the lowest, indicating the least acidified state of all the North American margins. In addition, elevated TA values in North America’s largest river,

the Mississippi, cause the northern GOM to have one of the highest TA-to-salinity ratios (~75) in the world ocean (Fig. 2e)29,36,42,43. Sea surface _p_CO2 and pH show more complex spatial

patterns (Fig. 3a, c). These parameters exhibit no significant co-variation with SST and weak (or no) co-variation with DIC/TA and the percent saturation of dissolved oxygen (DO%) in surface

waters, an indicator of biological activity (Supplementary Fig. 2 and Table 3). This is likely due to the influence of multiple competing processes along the Atlantic and GOM coasts. By

normalizing the _p_CO2 and pH values to 25 °C (i.e., setting the thermodynamic constants to 25 °C in a closed-system calculation), a south-to-north pattern becomes apparent with high

_p_CO2@25 °C and low pH@25 °C values in the cold northern regions. A comparison of _p_CO2 and pH distributions at in situ SST and at 25 °C not only reveals the important role of temperature

in seawater carbonate system thermodynamic equilibrium, but, perhaps more importantly, also the role of gas exchange in eliminating the temperature-induced air–sea disequilibrium. In other

words, high DIC/TA exists in cold northern waters mainly due to atmospheric CO2 uptake induced by low SST. In mid-latitude regions, low observed _p_CO2 and high observed pH appear in areas

of high DO%, suggesting biological CO2 removal there (e.g., early summer in the Gulf of Maine, Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. 2)44. In northern GOM coastal waters, low _p_CO2 and high pH

values (at both SST and 25 °C, Fig. 3a–d) strongly correlate with the low salinity, high DO%, and low DIC/TA ratios in the nutrient-rich Mississippi River plume-influenced region, revealing

the importance of local biological CO2 removal driven by riverine nutrients (Supplementary Table 3). The rest of the GOM has relatively high _p_CO2 and low pH, reflecting the warm climate

and low biological production in offshore waters42. Carbonate precipitation is another process that could be contributing to the relatively high _p_CO2 and low pH conditions. This is

supported by a slightly lower TA/SSS ratio (Fig. 2e) and a higher DIC/TA ratio (Fig. 2f, Supplementary Fig. 4) in southern GOM, indicating more TA removal than DIC removal. Precipitation

likely occurs in waters above CaCO3-rich banks at the Florida Keys and Yucatan peninsula, but can also happen in other areas45. Most strikingly, along the entire Atlantic and GOM coasts, the

large-scale spatial distribution of Ωarag, an important metric for ocean acidification stress on organisms, bears little resemblance to the distributions of _p_CO2 and pH (Fig. 3). Rather,

the Ωarag distribution is similar to SST and is inversely correlated with the DIC/TA ratio (_r_ = −0.996, _p_ < 0.001 in the Atlantic, see Supplementary Table 3 for other margins). Thus,

similar to the strong DIC/TA and temperature gradients, there is a strong south-to-north decline in Ωarag. Interestingly, Ωarag and its associated parameters (e.g., [\({\mathrm{CO}}_3^{2 -

}\)], Supplementary Fig. 3), but not _p_CO2 and pH, change abruptly at Cape Hatteras, where the Gulf Stream moves offshore and the influence of the Labrador Current increases in coastal

waters. The highest Ωarag appears in the GOM, which is consistent with the existence of the highest SST and TA and lowest DIC/TA ratio there. Strong biological CO2 removal in the Mississippi

River plume also contributes to low DIC/TA ratio and high Ωarag values in local surface waters42. Finally, distinct from _p_CO2 and pH, temperature-normalizing Ωarag does not alter the

south-to-north spatial pattern in the Atlantic and GOM coasts (Fig. 3f). THE CALIFORNIA CURRENT SYSTEM The California Current System (CCS) extends from roughly the US-Canadian border to Baja

California and is characterized by narrow shelves with strong, cold equatorward alongshore currents, and wind-driven upwelling events from late spring to early fall (Supplementary Fig.

1)46,47,48. While upwelling strength may vary, the observed carbonate chemical patterns are largely consistent (2007 and 2016 data were collected in late spring, while 2011, 2012, and 2013

data were collected in late summer) (Figs. 2 and 3). Here, similar to SSS, TA shows a weak south-to-north-decreasing gradient (Supplementary Table 3), while DIC has only a slightly stronger

south-to-north-decreasing gradient46. As a result, there is no coherent meridional gradient in the DIC/TA ratio, reflecting different mechanisms at play from those along the Atlantic and

Gulf coasts. However, higher _p_CO2 and lower pH values are generally observed in the south. As reported previously, _p_CO2 is high and pH is low near coastal upwelling centers in the CCS

(Fig. 3)27,49. These hot spots are caused by the strong upwelling of subsurface waters with high DIC/TA ratios and low O2, pH, and Ωarag values caused by biological respiration and

anthropogenic CO2 (Supplementary Fig. 5 and Table 3)27,47. An interesting characteristic of the CCS, offshore of the immediate upwelling centers, is that _p_CO2 is generally lower and pH is

higher relative to the Atlantic and GOM coasts at similar latitudes. This is mainly a result of the strong biological compensation following upwelling and incomplete compensation by air-sea

gas exchange in the CCS as shown by field observations49 and a numerical model47. However, once the temperature is normalized to 25 °C, such CCS vs. Atlantic contrasts largely disappear

(Fig. 3). This reflects the important role of low SST values in keeping _p_CO2 low and pH high via thermodynamic equilibrium shift and in maintaining a significant air–sea disequilibrium. In

contrast, Ωarag is almost ubiquitously low along the entire CCS coast relative to the GOM and southern Atlantic margins. It is particularly notable that, distinct from _p_CO2 and pH,

normalization to 25 °C does not alter this Ωarag contrast between the West and East Coasts. Low SST in the CCS allows more CO2 to be retained in the CO2-rich upwelling waters due to a

greater gas solubility, which keeps [\({\mathrm{CO}}_3^{2 - }\)] low (Eq. 1). Thus, the seemingly paradoxical co-existence of relatively high pH and low Ωarag in the CCS reflects the

distinct sensitivities of these parameters to thermodynamic constants, gas exchange, mixing, and biological processes. OTHER PACIFIC COASTAL REGIONS The Gulf of Alaska has the widest

continental shelves on the Pacific coast and is characterized by poleward winds and downwelling surface circulation during summer months50. Sea surface _p_CO2 is low and pH is high in these

relatively high-latitude, cold waters (Fig. 3), while Ωarag is ubiquitously low. In Mexican Pacific coastal waters, south of the Gulf of California, SST is particularly high, while SSS and

TA are similar to its northern neighbor (the CCS)51. Here, _p_CO2 and pH values generally align with the weak south-to-north trends of Pacific coastal waters; however, DIC and DIC/TA are

notably lower and Ωarag is much higher than the waters to the north (Figs. 2 and 3). THE REVELLE FACTOR DISTRIBUTIONS The capacity of seawater to resist a change in its acid–base properties

in response to a DIC perturbation caused by CO2 uptake from the atmosphere, or other processes, is important when considering the impacts of ocean acidification9,10,52,53. The

characteristics of how each carbonate system species will respond to such a disturbance can be described with a set of buffer factors41,54,55. Among them, the Revelle factor (RF) is most

often used, $${\mathrm{RF}} = \frac{{\Delta p{\mathrm{CO}}_{2}}}{{p{\mathrm{CO}}_{2}}}/\frac{{\Delta \mathrm{DIC}}}{{\mathrm{DIC}}},$$ (3) which is the fractional change of the CO2 species

to a fractional DIC change at constant SST, SSS, and TA. A lower RF indicates a greater buffer capacity and a lower sensitivity of seawater _p_CO2 to changes in DIC. Spatial distributions of

RF (Fig. 4a) show clear meridional gradients along the Atlantic margin, but no such pattern in the CCS. This suggests that the most buffered waters are in the GOM, southern US East Coast,

and Mexican Pacific coast. The least buffered waters, which may be most sensitive to increasing ocean carbon content, are in the CCS upwelling centers and the mid to northern Atlantic waters

of our study domain. In other words, the change in _p_CO2, pH, and Ωarag per unit DIC increase will be larger in the upwelling-dominated CCS waters and northern Atlantic waters than in

other coastal waters of the North American margin. However, next to upwelled waters with characteristically high RF in the CCS, strong biological removal of CO2 substantially increases the

buffer capacity as indicated by the low RF values associated with high DO% and low nitrate at around 12 °C in Fig. 4c, d. The spatial patterns of RF are similar and closely correlated to

[\({\mathrm{CO}}_3^{2 - }\)] and Ωarag (Figs. 3e, 4a, b and Supplementary Fig. 3 and Table 3), supporting the notion that the \({\mathrm{CO}}_3^{2 - }\) concentration plays a critical role

in the ability to resist acidification as added anthropogenic or respiratory CO2 is largely neutralized by \({\mathrm{CO}}_3^{2 - }\) to form \({\mathrm{HCO}}_3^ -\) (Eq. 2). Thus,

[\({\mathrm{CO}}_3^{2 - }\)], Ωarag and inversely the DIC/TA ratio (Fig. 2f) are good proxies or easy-to-understand surrogates for seawater buffer capacity. In all North American margin

waters, the DIC/TA ratio is inversely correlated with [\({\mathrm{CO}}_3^{2 - }\)] and Ωarag (Supplementary Table 3). In seawater, the point at which DIC/TA ≈ 1 (or DIC ≈ TA) represents the

most sensitive state of the system to CO2 addition because, at this point, [CO2] ≈ [\({\mathrm{CO}}_3^{2 - }\)] and pH = −0.5 log(_K_1_K_2) − 0.5 log([CO2]/[\({\mathrm{CO}}_3^{2 - }\)])

changes the fastest17. Also note that this point (pH ≈ −0.5 log(_K_1_K_2)) occurs at a higher pH in cold waters (7.71 at 3 °C and 7.60 at 10 °C) than in warm waters (7.35 at 30 °C)

(Supplementary Fig. 6), making cold waters more sensitive to CO2 addition56. The cold waters of the northeastern margins, Alaskan shelf, and the CCS upwelling centers are approaching this

point and are thus most vulnerable to ocean acidification. CONTINENTAL-SCALE PATTERN VS. LOCAL VARIABILITY To explore the first-order controlling mechanisms on large-scale spatial patterns

of carbonate chemistry parameters on contrasting margins, we first compare field-observed DIC, _p_CO2, pH, and Ωarag distributions with those predicted from gas equilibrium with atmospheric

CO2. We do this by calculating each of these parameters from SST, SSS, and TA under the assumption of sea surface CO2 gas equilibrium with the atmosphere. Over a large latitudinal range

involving multiple water masses along the North American Atlantic and GOM coasts, DIC and Ωarag generally follow air–sea gas equilibrium-based predictions on a seasonal timescale (months)

(Fig. 5a, b, e, f). This atmospheric CO2 equilibrium control mechanism would dictate a relatively high DIC and low Ωarag in cold northern waters, where CO2 solubility is high and the

acid–base equilibrium favors the neutralization of CO2 and \({\mathrm{CO}}_3^{2 - }\) to \({\mathrm{HCO}}_3^ -\) (Eqs. 1 and 2; Fig. 1a). In contrast, relatively low DIC and high Ωarag

conditions would occur in warmer southern waters, where CO2 solubility and _K_1/K2 are lower, favoring \({\mathrm{HCO}}_3^ -\) dissociation to CO2 and \({\mathrm{CO}}_3^{2 - }\) with CO2

degassing to the atmosphere. Such distribution patterns are known in global open-ocean basins5,6,7,36,57 but have not been reported before in more dynamic coastal oceans. The fact that the

DIC/TA ratio is lowest in the GOM and highest in northern Atlantic coastal waters reflects the temperature-regulated gas equilibrium and acid–base equilibrium shift. The observations of

particularly low DIC/TA ratio and high Ωarag in the Mexican Pacific margin (Figs. 2f and 3e) further support the argument made here that air–sea gas equilibrium largely controls DIC and

Ωarag in surface waters. This is true even in the region that is located right above the North Eastern Tropical Pacific (15–20°N, 100–110°W) oxygen minimum zone with elevated DIC

concentrations of 2200 μmol kg−1 at a depth of only 50 m (ref. 51). To the north in the Gulf of Alaska, however, slightly lower DIC and higher Ωarag than predicted from atmospheric

equilibration are likely due to legacy effects of strong biological CO2 removal in late spring and early summer (Fig. 5c)50. Along the CCS, however, while atmospheric equilibrium still

exerts strong control on DIC, upwelling and subsequent biological utilization of CO2 have greatly modified the DIC concentrations in coastal waters. These processes have variable timescales

of days to weeks46,47,49 and are much less than the timescales of gas equilibration (one to a few months). The association of a positive DIC deviation with low temperature and high

nutrients, a sign of upwelling (Fig. 5c, d), confirms that the source of DIC is from CO2-rich subsurface waters that have been upwelled in the CCS. The impact of upwelling and biology

becomes greater for Ωarag, which deviates substantially from the atmospheric equilibrium-based prediction in the CCS (Fig. 5g, h). Despite the strong role of air–sea gas exchange, observed

pH and _p_CO2 values can deviate greatly from those at atmospheric equilibrium even in the Atlantic and GOM coasts (Fig. 5i, j, m, n). This is particularly true in the CCS where strong

upwelling (high nutrient) or biological production (low nutrient) lead to extreme pH and _p_CO2 values, whereas the expected pH and _p_CO2 from the atmospheric equilibrium are nearly

invariable (Fig. 5k, l, o, p). Deviations of DIC, Ωarag, and pH from gas equilibration are highly correlated with positive or negative deviations of seawater _p_CO2 from atmospheric _p_CO2

on all margins (Supplementary Fig. 7). In the CCS, the positive deviation in DIC and negative deviations in Ωarag and pH are associated with CO2 supersaturation induced by the upwelling of

CO2-rich subsurface waters, while the opposite conditions (CO2 undersaturation) are associated with the subsequent stimulation of biological production27,47. In the GOM, such deviations are

controlled by biological CO2 removal in the low-salinity river plume and net respiration and CaCO3 precipitation in the high-salinity waters. On the Atlantic coast, a combination of

temperature changes associated with physical transport by large-scale alongshore currents, biological CO2 removal, and local terrestrial exports are all at play (Supplementary Fig. 7).

SENSITIVITY OF CARBONATE CHEMISTRY TO PERTURBATIONS A fundamental question to ask is why do DIC and Ωarag generally follow air–sea gas equilibrium-based predictions in the Atlantic and Gulf

coasts, while pH and _p_CO2 distributions are decoupled from the atmospheric equilibrium and are most sensitive to local physical and biological modifications? We contend that this is mainly

the result of two factors. First and most importantly, the temperature effect on carbonate chemistry has two components, one is the internal effect on the thermodynamic equilibrium

constants, including the acid–base dissociation constants _K_1 and _K_2 and the solubility constant _K_0 under no gas exchange conditions, while the other is the external effect related to

DIC concentration changes caused by gas exchange. As shown in Fig. 1, in an open system these two temperature effects tend to cancel each other out completely for pH and _p_CO2 and partially

for [CO2], but have an additive effect for [\({\mathrm{CO}}_3^{2 - }\)], DIC, and Ωarag, with the gas equilibrium playing the dominant role. Thus, moderate carbonate system perturbations

caused by local physical and biological processes are essentially overshadowed for DIC and Ωarag due to their large latitudinal gradients along the Atlantic and GOM margins associated with

the south-to-north temperature gradient, but are apparent for pH and _p_CO2, which have no clear meridional trends. The contrasting temperature effects are also compounded by the fact that

physical and biological addition and removal of DIC act linearly, while their impacts on _p_CO2 changes are non-linear. Second, while the internal temperature effect and upwelling of high

DIC subsurface waters are essentially instantaneous or of short timescale, air–sea gas exchange compensates carbonate chemistry changes over monthly timescales. As a result, slow-acting

surface processes such as cooling in poleward-moving currents along the Atlantic coast are largely compensated and appear to have relatively small impacts on surface seawater carbonate

chemistry. The processes that contribute most visibly to carbonate chemistry, in particular _p_CO2 and pH variability, are those that act much faster than the timescales of gas equilibrium

(e.g., upwelling, river input, and primary production, which lack SST-related meridional trends)36. These factors also contribute to the observed sensitivity differences of pH and Ωarag to

anthropogenic, physical, and biological processes in the CCS upwelling waters. In these waters, excess CO2 relative to CO2 expected from equilibration with a preindustrial atmosphere comes

from both subsurface organic carbon respiration and anthropogenic CO2 obtained when subsurface water masses were previously in contact with the atmosphere. These sources can combine to

create seawater that greatly exceeds even the anthropogenically elevated modern atmospheric _p_CO2 and cause pH and Ωarag in the newly upwelled waters to be much lower than they would be at

atmospheric equilibrium (Supplementary Fig. 7). Subsequent CO2 degassing and biological blooms can reduce CO2 and increase pH and Ωarag. A very strong correlation between DO and Ωarag in the

CCS (Supplementary Table 3a) suggests that biological drawdown of DIC and upwelling of waters rich in respired DIC together overpower the influence of the small latitudinal SST-gradient in

this region. However, generally lower temperatures in the CCS (compared to the GOM and south Atlantic regions) and incomplete compensation by gas exchange allow these waters to

simultaneously have relatively high pH but low Ωarag because the effects of low temperature outweigh the impacts of biological CO2 removal for Ωarag but not for pH (Supplementary Fig. 8).

The same discussion applies to high-latitude waters in the Labrador Sea in the Atlantic and Gulf of Alaska in the Pacific all have high pH but low Ωarag, although in these places, the main

driver for a low Ωarag is the high CO2 solubility at low SSTs and the main driver for a high pH is the biological CO2 removal. TIMESCALES OF COASTAL OCEAN PROCESSES To support the

conclusions derived from the field data and first principle-based analysis and to further explore the different responses of carbonate parameters to atmospheric forcing and local physical

and biological processes, we simulated seasonal changes in carbonate chemistry using a time-variable box model for the Atlantic coast. The model simulates carbonate parameter changes and the

associated gas exchange flux in an idealized surface mixed layer following prescribed time series of salinity, temperature, wind, biological production, and vertical exchange with the

subsurface water (see details in the “Methods” section). In the northeastern margin, SST follows a typical seasonal cycle, while SSS is high in winter and decreases to a minimum in summer as

a result of changing river discharge and meltwater supply37 (Fig. 6a). As expected, surface water _p_CO2 increases and pH decreases from spring to summer following the seasonal warming and

display opposite behavior from summer to fall following cooling (Fig. 6b). This thermal seasonality is enhanced by high riverine CO2 export and reduced by spring biological blooms35. The

_p_CO2 decrease and pH increase in the summer to fall cooling period are also enhanced by biological blooms and decreased river discharge. In the meantime, in contrast, DIC increases toward

winter and decreases toward summer, whereas Ωarag decreases toward winter and increases toward summer (Fig. 6c). For comparison with the box model simulation, we also calculate carbonate

system parameters while assuming instantaneous equilibrium between sea surface _p_CO2 and the atmosphere (open system conditions). The full-model Atlantic margin _p_CO2 and pH values

completely decouple from the values expected from atmospheric equilibrium, but track water mass property changes associated with seasonal temperature variations and short-term local physical

and biological processes. Note that the equilibrium values exhibit a much smaller range of _p_CO2 and pH variability due to cancellation of the two temperature effects under the imposed

conditions where gas exchange is instantaneous (Fig. 1 and Fig. 6b, d, e). In contrast, the modeled DIC and Ωarag values approximately track those predicted by instantaneous equilibrium with

atmospheric CO2, although with a time lag of 1–2 months. Here a seasonal DIC maximum and Ωarag minimum occur during winter when CO2 solubility is the highest with opposing results found

during summer (Fig. 6c, f, g). These model-derived behaviors are consistent with the field observations and our mechanistic interpretation of them; although seasonal SST variations are used

to illustrate the carbonate chemistry behaviors in the simple box model, latitudinal SST variations are reflected in the summertime observations along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts.

Interestingly, modeled _p_CO2 and pH values also show the high-frequency signals of SST and SSS variations caused by local short-term processes reflected in SST and SSS changes. In contrast,

the impacts of high-frequency local processes are largely absent in the modeled DIC and greatly dampened in modeled Ωarag values (Fig. 6). When a disturbance (vertical mixing with high DIC

subsurface water) is introduced (with a sudden increase of DIC), with all other conditions unchanged, the _e_-folding time of CO2 system restoration (that is the disturbance is reduced to

1/_e_ or 37% of the initial value) due to degassing varies from 10 days at very high gas exchange rates (to mimic an instantaneous gas equilibration) to more than 100 days at low gas

exchange rates (approaching a closed system) with ~1 month at an average wind condition and typical mixed-layer depths (Supplementary Fig. 9). In general, two to three _e_-folding intervals

are needed for a disturbed signal to be completely erased. Increases in the associated nutrient input, and thus net biological production, will have an opposite effect and speed up the

restoration (not shown). Thus the very different carbonate chemistry behaviors reported in this work reflect timescales of physical, chemical, and biological processes differ from

instantaneous thermodynamic equilibrium, including rapid local physical processes (upwelling, mixing, etc.) acting on timescales of days to weeks, biological production (weeks), alongshore

current transport (months), gas exchange processes (months to seasonal), and the seasonal thermal cycle. DISCUSSION Our study illustrates that, as in the open ocean, the large-scale

meridional gradient in surface water temperature regulates CO2 gas equilibration with the atmosphere and plays a first-order role in determining the spatial distributions of DIC and Ωarag on

seasonal timescales in non-upwelling-dominated ocean margins. In contrast, _p_CO2 and pH variations are more reflective of short-term, local modifications by coastal ocean physical and

biological processes. In upwelling-dominated regions along eastern boundary current ocean margins, however, the atmospheric CO2 equilibrium mechanism is perturbed much more than that along

other ocean margins and in the open ocean5,6,8,36,58. This is because dynamic coastal conditions further accentuate the contrasts between longer timescale air–sea equilibrium in slowly

moving coastal currents and modifications by short-term, local physical and biological processes. As such, the two commonly used ocean acidification metrics, pH and Ωarag, can vary quite

differently in upwelling vs. non-upwelling-dominated systems and in warm southern vs. cold northern waters. As organisms respond to pH and Ωarag differently (both during development and

calcification)14, our findings emphasize the importance of examining multiple aspects of organismal and ecosystem responses to ocean acidification with respect to _p_CO2, pH, Ωarag, and DIC

changes under warmer and higher CO2 future ocean conditions. Recently, contrasting seasonal cycle responses of Ωarag, [H+], pH, and _p_CO2 to DIC increases throughout the global surface

ocean have been shown with observations10 and models9,11,13,59. These findings, in addition to a more localized, estuarine study60, suggest that seasonal (and higher-frequency) variability

may intensify more rapidly on upwelling-dominated and cold high-latitude margins due to their naturally lower buffering capacity and higher sensitivity to increasing CO2 content in the

ocean. However, the absolute rates of Ωarag decrease are faster in warm and high Ωarag tropical and subtropical waters26. Our work further shows that there are substantial spatial

differences in buffering capacities across the North American ocean margins and these differences imply a natural disparity in regional sensitivities to ocean acidification. In particular,

the RF distribution clearly draws our attention to ecosystems—including the CCS and northern-latitude coastal regions, such as the Gulf of Maine (Atlantic) and the Gulf of Alaska

(Pacific)—as being particularly sensitive and vulnerable to anthropogenic CO2 forcing. METHODS DESCRIPTION OF THE FIELD PROGRAM Starting in 2007, under the auspices of National Oceanic and

Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)’s Climate Program Office and, since its inception in 2010, Ocean Acidification Program, NOAA Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory and NOAA Atlantic

Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory, in collaboration with academic partners and international collaborators, have conducted multiple surveys of the North American ocean margins. The

most recent quality-controlled survey data are from the _E_ast Coast Ocean Acidification (ECOA) and Gulf of Alaska cruises in summer 2015, the West Coast Ocean Acidification (WCOA) cruise

in late spring 2016, and the GOM Ecosystem and Carbon Cycle (GOMECC) cruise in summer 2017. Results from these cruises are presented in Fig. 2 and 3 along the coastlines of the North

American continent and associated ocean margins, while previous cruises in the same regions (West Coast: late spring 2007 and late summer 2011, 2012, and 2013; GOM and Atlantic: summer 2007

and 2012). In addition, data from the Scotian Shelf and Labrador Sea as well as the Mexico Pacific coast, although limited, are included to extend the geographic coverage. Supplementary

Table 2 summarizes the relevant cruise information. In this work, all DIC samples were measured at sea by coulometric titration using a modified Single-Operator Multi-Metabolic Analyzer

system, and TA was measured by acidimetric titration using the open cell method61,62. Both DIC and TA measurements were calibrated daily using Certified Reference Materials from Dr. Andrew

Dickson’s laboratory at Scripps Institution of Oceanography. The overall uncertainty of each of these two measurements is ±2 µmol kg−1. DO was measured by a Winkler titration technique.

Detailed descriptions are available at, for ECOA 2015, [https://www.nodc.noaa.gov/oads/data/0159428.xml] or [https://doi.org/10.7289/v5vt1q40], for WCOA 2016,

[https://www.nodc.noaa.gov/oads/data/0169412.xml] or [https://doi.org/10.7289/v5v40shg], for GOMECC 2017, [https://www.nodc.noaa.gov/oads/data/0188978.xml] or

[https://doi.org/10.25921/yy5k-dw60], and for AZMP, [https://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/science/data-donnees/biochem/index-eng.html]. For the purpose of examining spatial distributions, pH, _p_CO2,

and Ωarag were calculated from DIC and TA together with nutrient concentrations using the CO2SYS program63 applying the carbonic acid dissociation constants of Mehrbach et al.64 as refitted

by Dickson and Millero65. We use the DIC–TA pair because both parameters are available and were measured at high quality during all cruises. Good internal consistency among multiple

parameters was observed and potential issues were identified in an earlier study66. pH is expressed on the total proton concentration scale67. Ωarag is defined as the concentration product

of dissolved calcium and carbonate ions divided by the aragonite mineral solubility product68. DIC, ΩARAG, PH, AND _P_CO2 AT EQUILIBRIUM WITH ATMOSPHERIC _P_CO2 The values at equilibrium are

calculated assuming that seawater _p_CO2 is in equilibrium with annual mean atmospheric _p_CO2. In this case, the input pair to CO2SYS is _p_CO2 and TA. The atmospheric CO2 data, as a dry

air mole fraction, was obtained from the Mauna Loa Observatory, Hawaii. BOX-MODEL SIMULATION To study the relationships that control surface-ocean carbonate parameters and air–sea CO2

fluxes, we use a box model to simulate an idealized mixed layer. The box model simulates the carbonate systems as a homogeneous surface-ocean water mass located either in the North-West

Atlantic (NWA, 40.1–42.5°N, 69.2–67.5°W) and South Atlantic Bight (SAB, 28.3°N–29.7°N, 77.6°W–79.2°W). The model is driven by realistic temperatures and salinities from the Mercator 1/12°

data-assimilated General Circulation Model with a daily resolution in time69. The carbonate system is defined from DIC and TA and re-adjusted to changes in temperature and salinity at each

time step using the CO2SYS package63. Throughout the model simulation, TA is calculated from prescribed salinity61,69. The model is initiated with the carbonate system defined by _p_CO2 in

equilibrium with atmospheric values and TA (TA_t_0) defined by initial salinity70. DIC is calculated from _p_CO2(aq), TA_t_0, temperature, and salinity at _t_ = 0. The model is spun up for

180 days using prescribed physical and biological conditions as described above. _p_CO2__t_(aq) is calculated using CO2SYS as well. ΔDICBio and ΔDICVertical are prescribed (see below), while

Δ_p_CO2_air–sea is calculated at each time step using the relationship Δ_p_CO2_air–sea = 0.24 × _k_ × _K_0 × (_p_CO2__t_(aq) − (_p_CO2_(atm)). _K_0 is the CO2 gas solubility71 and _k_ is

defined as _k_ = 0.251 × _W_2 × (_Sc_/660)−0.5, where _W_ is wind speed in m s−1 and _Sc_ is the Schmidt number72,73. Biological production is assessed from weekly averages of daily changes

in satellite-derived chlorophyll (Chl) for the year 2015 using the daily MODIS aqua 4-km level 3 product74. We extract daily time series for each grid cell that falls within the NWA and SAB

model regions, identify all pairs of consecutive days with valid data, and convert changes in Chl to a carbon flux by using a fixed C:Chl ratio of 60 (ref. 75). The resulting weekly averages

are interpolated to daily time series. The resulting change in DIC due to biological production is significantly smaller than other sources and sinks in the current study. The highest net

community production (NCP) values we get are on the order of 0.1 mmol C day−1 m−3. This corresponds to ~50 mg C m−2 day−1. Satellite-derived net primary production (NPP) is on the order of

400 mg C m−2 day−1 and with an expected NCP to NPP ratio of ~10%; thus, our biological production parameters are reasonable. Winds are prescribed to 7 m s−1 in the summer and 10.5 m s−1 in

the winter, to be consistent with representative wind data from the NOAA/Seawinds blended wind data set69. Winter mixing in NWA is simulated by adding 0.1 mmol m−3 DIC daily from October to

February (over 155 days). The value is based on a scaling analysis of vertical DIC gradients and diffusivity estimates in the region based on observational in 2015 in the NWA region.

Literature values of physical vertical diffusion combined with vertical profiles of DIC from the ECOA 2015 cruise suggests that diffusive transports of DIC is negligible during summer. We

use constant winds to minimize noise and to isolate the effect by changes in solubility on the carbonate system. Atmospheric _p_CO2 is set to 395 μatm. Specifically, the forward iteration

from time _t___n_ to _t___n_ + 1 is performed by the following steps: DIC_t_ + 1 = DIC_t_ + Δ_p_CO2_air–sea + ΔDICBio + ΔDICVertical. * 1. Calculate the carbonate system defined by

temperature, salinity, DIC, and TA at _t___n_. * 2. Apply changes to the DIC concentration at _t___n_ + 1 by biological processes, vertical mixing and air–sea exchange (based on _p_CO2

values at _t___n_). * 3. Recalculate the carbonate system using temperature, salinity, and TA at _t___n_, and DIC at _t___n_ + 1. * 4. Record pH, _p_CO2, and Ωarag at _t___n_ + 1. The reason

to use temperature, salinity, and TA at _t___n_ when performing step 3 is to make sure that all carbon parameters are calculated using the same physical conditions. All the details are

given inside the coding: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3833678. We also calculate DICeq, a property that is based on the same TA, salinity, and temperature as the model but with _p_CO2(aq)

relaxed to _p_CO2(atm), which can be interpreted as the air–sea exchange being infinitely fast. Here for simplicity, we assume _p_CO2(atm) equals the dry CO2 mole fraction. STATISTICAL

INFORMATION We used the built-in Matlab function (corrcoef) to compute the correlation coefficients (https://www.mathworks.com/help/matlab/ref/corrcoef.htl). DATA AVAILABILITY Discrete

bottle data from all NOAA ocean acidification regional research cruises are available at NOAA’s National Centers for Environmental Information. For ECOA 2015,

[https://www.nodc.noaa.gov/oads/data/0159428.xml] or [https://doi.org/10.7289/v5vt1q40]; for WCOA 2016, [https://www.nodc.noaa.gov/oads/data/0169412.xml] or

[https://doi.org/10.7289/v5v40shg]; for GOMECC 2017, [https://www.nodc.noaa.gov/oads/data/0188978.xml] or [https://doi.org/10.25921/yy5k-dw60], and for AZMP,

[https://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/science/data-donnees/biochem/index-eng.html]. Atmospheric CO2 data are available at https://www.esrl.noaa.gov/gmd/ccgg/trends/data.html. CODE AVAILABILITY The box

model was written in python and the code can be found at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3833678. REFERENCES * Bates, N. R. et al. Detecting anthropogenic carbon dioxide uptake and ocean

acidification in the North Atlantic Ocean. _Biogeosciences_ 9, 2509–2522 (2012). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Orr, J. C. et al. Anthropogenic ocean acidification over the

twenty-first century and its impact on calcifying organisms. _Nature_ 437, 681–686 (2005). Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Caldeira, K. & Wickett, M. E. Anthropogenic carbon

and ocean pH. _Nature_ 425, 365 (2003). Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Brewer, P. G. A changing ocean seen with clarity. _Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA_ 106, 12213–12214 (2009).

Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Takahashi, T. et al. Climatological distributions of pH, _p_CO2, total CO2, alkalinity, and CaCO3 saturation in the global surface ocean, and

temporal changes at selected locations. _Mar. Chem._ 164, 95–125 (2014). Article CAS Google Scholar * Jiang, L.-Q. et al. Climatological distribution of aragonite saturation state in the

global oceans. _Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles_ 29, 2015GB005198 (2015). Article CAS Google Scholar * Völker, C., Wallace, D. W. R. & Wolf-Gladrow, D. A. On the role of heat fluxes in the

uptake of anthropogenic carbon in the North Atlantic. _Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles_ 16, 85–89 (2002). Article CAS Google Scholar * Jiang, L.-Q., Carter, B. R., Feely, R. A., Lauvset, S. K.

& Olsen, A. Surface ocean pH and buffer capacity: past, present and future. _Sci. Rep._ 9, 18624 (2019). Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * McNeil, B. I. &

Sasse, T. P. Future ocean hypercapnia driven by anthropogenic amplification of the natural CO2 cycle. _Nature_ 529, 383–386 (2016). Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Landschützer,

P., Gruber, N., Bakker, D. C. E., Stemmler, I. & Six, K. D. Strengthening seasonal marine CO2 variations due to increasing atmospheric CO2. _Nat. Clim. Chang._ 8, 146–150 (2018).

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Kwiatkowski, L. & Orr, J. C. Diverging seasonal extremes for ocean acidification during the twenty-first century. _Nat. Clim. Chang._ 8, 141–145

(2018). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Perez, F. F. et al. Meridional overturning circulation conveys fast acidification to the deep Atlantic Ocean. _Nature_ 554, 515 (2018). Article

ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Fassbender, A. J., Rodgers, K. B., Palevsky, H. I. & Sabine, C. L. Seasonal asymmetry in the evolution of surface ocean _p_CO2 and pH thermodynamic

drivers and the influence on sea–air CO2 flux. _Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles_ 32, 1476–1497 (2018). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Waldbusser, G. G. et al. Ocean acidification has multiple

modes of action on bivalve larvae. _PLoS ONE_ 10, e0128376 (2015). Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Albright, R. et al. Carbon dioxide addition to coral reef waters

suppresses net community calcification. _Nature_ 555, 516 (2018). Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Riebesell, U. & Gattuso, J.-P. Lessons learned from ocean acidification

research. _Nat. Clim. Chang._ 5, 12 (2014). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Cai, W.-J. et al. Acidification of subsurface coastal waters enhanced by eutrophication. _Nat. Geosci._ 4,

766–770 (2011). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Feely, R. A. et al. The combined effects of ocean acidification, mixing, and respiration on pH and carbonate saturation in an urbanized

estuary. _Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci._ 88, 442–449 (2010). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Hagens, M. et al. Biogeochemical processes and buffering capacity concurrently affect

acidification in a seasonally hypoxic coastal marine basin. _Biogeosciences_ 12, 1561–1583 (2015). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Sunda, W. G. & Cai, W.-J. Eutrophication induced

CO2-acidification of subsurface coastal waters: Interactive effects of temperature, salinity, and atmospheric _P_ CO2. _Environ. Sci. Technol._ 46, 10651–10659 (2012). Article ADS CAS

PubMed Google Scholar * Silbiger, N. J. & Sorte, C. J. B. Biophysical feedbacks mediate carbonate chemistry in coastal ecosystems across spatiotemporal gradients. _Sci. Rep._ 8, 796

(2018). Article ADS PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Kleypas, J. A., Anthony, K. R. N. & Gattuso, J.-P. Coral reefs modify their seawater carbon chemistry—case study from

a barrier reef (Moorea, French Polynesia). _Glob. Chang. Biol._ 17, 3667–3678 (2011). Article ADS Google Scholar * Signorini, S. R. et al. Surface ocean _p_CO2 seasonality and sea-air

CO2 flux estimates for the North American east coast. _J. Geophys. Res. Ocean_ 118, 1–22 (2013). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Wang, Z. A. et al. The marine inorganic carbon system

along the Gulf of Mexico and Atlantic coasts of the United States: insights from a transregional coastal carbon study. _Limnol. Oceanogr._ 58, 325–342 (2013). Article ADS CAS Google

Scholar * Wanninkhof, R. et al. Ocean acidification along the Gulf Coast and East Coast of the USA. _Cont. Shelf Res._ 98, 54–71 (2015). Article ADS Google Scholar * Feely, R. A. et al.

The combined effects of acidification and hypoxia on pH and aragonite saturation in the coastal waters of the California current ecosystem and the northern Gulf of Mexico. _Cont. Shelf Res._

152, 50–60 (2018). Article ADS Google Scholar * Feely, R. A., Sabine, C. L., Hernandez-Ayon, J. M., Ianson, D. & Hales, B. Evidence for upwelling of corrosive ‘acidified’ water onto

the continental shelf. _Science (80)_ 320, 1490–1492 (2008). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * DeGrandpre, M. D., Olbu, G. J., Beatty, C. M. & Hammar, T. R. Air–sea CO2 fluxes on the

US Middle Atlantic Bight. _Deep. Res. Part II_ 49, 4355–4367 (2002). Article CAS Google Scholar * Huang, W.-J., Cai, W.-J., Wang, Y., Lohrenz, S. E. & Murrell, M. C. The carbon

dioxide system on the Mississippi River-dominated continental shelf in the northern Gulf of Mexico: 1. Distribution and air–sea CO2 flux. _J. Geophys. Res. Ocean_ 120, 1429–1445 (2015).

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Jiang, L.-Q., Cai, W.-J. & Wang, Y. A comparative study of carbon dioxide degassing in river- and marine-dominated estuaries. _Limnol. Oceanogr._ 53,

2603–2615 (2008). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Salisbury, J., Green, M., Hunt, C. & Campbell, J. Coastal acidification by rivers: a threat to shellfish? _Eos Trans. AGU_ 89,

513–514 (2008). Article ADS Google Scholar * Borges, A. V. & Gypens, N. Carbonate chemistry in the coastal zone responds more strongly to eutrophication than ocean acidification.

_Limnol. Oceanogr._ 55, 346–353 (2010). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Fassbender, A. J., Sabine, C. L., Feely, R. A., Langdon, C. & Mordy, C. W. Inorganic carbon dynamics during

northern California coastal upwelling. _Cont. Shelf Res._ 31, 1180–1192 (2011). Article ADS Google Scholar * Fassbender, A. J., Sabine, C. L. & Feifel, K. M. Consideration of coastal

carbonate chemistry in understanding biological calcification. _Geophys. Res. Lett._ 43, 4467–4476 (2016). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Salisbury, J. E. & Jönsson, B. F. Rapid

warming and salinity changes in the Gulf of Maine alter surface ocean carbonate parameters and hide ocean acidification. _Biogeochemistry_ 141, 401–418 (2018). Article CAS PubMed PubMed

Central Google Scholar * Carter, B. R., Toggweiler, J. R., Key, R. M. & Sarmiento, J. L. Processes determining the marine alkalinity and calcium carbonate saturation state

distributions. _Biogeosciences_ 11, 7349–7362 (2014). Article ADS Google Scholar * Richaud, B., Kwon, Y.-O., Joyce, T. M., Fratantoni, P. S. & Lentz, S. J. Surface and bottom

temperature and salinity climatology along the continental shelf off the Canadian and U.S. East Coasts. _Cont. Shelf Res._ 124, 165–181 (2016). Article ADS Google Scholar * Atkinson, L.

P., Lee, T. N., Blanton, J. O. & Chandler, W. S. Climatology of the southeastern United States continental shelf waters. _J. Geophys. Res. Ocean_ 88, 4705–4718 (1983). Article ADS

Google Scholar * Wiseman, W. J., Rabalais, N. N., Turner, R. E., Dinnel, S. P. & MacNaughton, A. Seasonal and interannual variability within the Louisiana coastal current:

stratification and hypoxia. _J. Mar. Syst._ 12, 237–248 (1997). Article Google Scholar * Cai, W.-J. et al. Alkalinity distribution in the western North Atlantic Ocean margins. _J. Geophys.

Res._ 115, C08014 (2010). ADS Google Scholar * Egleston, E. S., Sabine, C. L. & Morel, F. M. M. Revelle revisited: buffer factors that quantify the response of ocean chemistry to

changes in DIC and alkalinity. _Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles_ 24, GB1002 (2010). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Guo, X. et al. Carbon dynamics and community production in the Mississippi

river plume. _Limnol. Oceanogr._ 57, 1–17 (2012). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Jiang, Z.-P., Tyrrell, T., Hydes, D. J., Dai, M. & Hartman, S. E. Variability of alkalinity and the

alkalinity-salinity relationship in the tropical and subtropical surface ocean. _Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles_ 28, 729–742 (2014). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Townsend, D. W. et al.

Water masses and nutrient sources to the Gulf of Maine. _J. Mar. Res._ 73, 93–122 (2015). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Davis, R. A. in _Habitats and Biota of the Gulf

of Mexico: Before the Deepwater_ Horizon _Oil Spill_ (ed. Ward, C.) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-3447-8_3 (2017). Chapter Google Scholar * Jacox, G., Moore, M., Edwards, A. &

Fiechter, J. Spatially resolved upwelling in the California Current System and its connections to climate variability. _Geophys. Res. Lett._ 41, 3189–3196 (2014). Article ADS Google

Scholar * Turi, G., Lachkar, Z. & Gruber, N. Spatiotemporal variability and drivers of _p_CO2 and air–sea CO2 fluxes in the California Current System: an eddy-resolving modeling study.

_Biogeosciences_ 11, 671–690 (2014). Article ADS Google Scholar * Hickey, B. M. The California current system—hypotheses and facts. _Prog. Oceanogr._ 8, 191–279 (1979). Article ADS

Google Scholar * Hales, B., Takahashi, T. & Bandstra, L. Atmospheric CO2 uptake by a coastal upwelling system. _Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles_ 19, GB1009 (2005). Article ADS CAS Google

Scholar * Evans, W., Mathis, J. T., Winsor, P., Statscewich, H. & Whitledge, T. E. A regression modeling approach for studying carbonate system variability in the northern Gulf of

Alaska. _J. Geophys. Res. Ocean_ 118, 476–489 (2013). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Franco, A. C. et al. Air–sea CO2 fluxes above the stratified oxygen minimum zone in the coastal

region off Mexico. _J. Geophys. Res. Ocean_ 119, 2923–2937 (2014). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Broecker, W. S., Takahashi, T., Simpson, H. J. & Peng, T.-H. Fate of fossil fuel

carbon dioxide and the global carbon budget. _Science (80)_ 206, 409 LP–409418 (1979). Article ADS Google Scholar * Sundquist, E. T., Plummer, L. N. & Wigley, T. M. L. Carbon-dioxide

in the ocean surface—homogeneous buffer factor. _Science (80)_ 204, 1203–1205 (1979). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Frankignoulle, M. A complete set of buffer factors for acid–base

CO2 system in seawater. _J. Mar. Syst._ 5, 111–118 (1994). Article Google Scholar * Álvarez, M. et al. The CO2 system in the Mediterranean Sea: a basin wide perspective. _Ocean Sci._ 10,

69–92 (2014). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Fassbender, A. J., Sabine, C. L. & Palevsky, H. I. Nonuniform ocean acidification and attenuation of the ocean carbon sink. _Geophys.

Res. Lett._ 44, 8404–8413 (2017). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Broecker, W. S. & Peng, T. H. _Tracers in the Sea_, 690pp (Eldigio, Palisades, New York, 1982). * Jiang, L.,

Carter, B. R., Feely, R. A., Lauvset, S. K. & Olsen, A. Surface ocean pH and buffer capacity: past, present, and future. _Sci. Rep._ 9, 18624 (2020). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar *

Hauck, J. & Völker, C. Rising atmospheric CO2 leads to large impact of biology on Southern Ocean CO2 uptake via changes of the Revelle factor. _Geophys. Res. Lett._ 42, 1459–1464

(2015). Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Pacella, S. R., Brown, C. A., Waldbusser, G. G., Labiosa, R. G. & Hales, B. Seagrass habitat metabolism increases

short-term extremes and long-term offset of CO2 under future ocean acidification. _Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA_ 115, 3870 LP–3873875 (2018). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Dickson, A.

G., Sabine, C. L. & Christian, J. R. Guide to best practices for ocean CO2 measurements. _PICES Spec. Publ._ 3, https://doi.org/10.1159/000331784 (2007). Article PubMed Google Scholar

* Johnson, K. M., Kortzinger, A., Mintrop, L., Duinker, J. C. & Wallace, D. W. R. Coulometric total carbon dioxide analysis for marine studies: measurement and internal consistency of

underway TCO2 concentrations. _Mar. Chem._ 67, 123–144 (1999). Article CAS Google Scholar * Van Heuven, S., Pierrot, D., Rae, J. W. B. & Wallace, D. W. R. _MATLAB Program Developed

for CO_ _2_ _System Calculations_. ORNL/CDIAC-105b, 530 (Carbon Dioxide Information Analysis Center, Oak Ridge National Laboratory, US Department of Energy, Oak Ridge, 2009). * Mehrbach, C.,

Culberson, C. H., Hawley, J. E. & Pytkowicz, R. M. Measurement of the apparent dissociation constants of carbonic acid in seawater at atmospheric pressure. _Limnol. Oceanogr._ 18,

897–907 (1973). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Dickson, A. G. & Millero, F. J. A comparison of the equilibrium constants for the dissociation of carbonic acid in seawater media.

_Deep Sea Res._ 34, 1733–1743 (1987). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Patsavas, M. C., Byrne, R. H., Wanninkhof, R., Feely, R. A. & Cai, W.-J. Internal consistency of marine

carbonate system measurements and assessments of aragonite saturation state: Insights from two U.S. coastal cruises. _Mar. Chem_. 176, 9–20 (2015). * Dickson, A. G. pH buffers for sea water

media based on the total hydrogen ion concentration scale. _Deep Sea Res._ 40, 107–118 (1993). Article CAS Google Scholar * Mucci, A. The solubility of calcite and aragonite in seawater

at various salinity, temperatures, and one atmosphere total pressure. _Am. J. Sci._ 283, 789–799 (1983). Article ADS Google Scholar * Lellouche, J.-M. et al. Evaluation of global

monitoring and forecasting systems at Mercator Océan. _Ocean Sci. Discuss._ 9, 1123–1185 (2012). Article ADS Google Scholar * Cai, W.-J. et al. Alkalinity distribution in the western

North Atlantic Ocean margins. _J. Geophys. Res. Ocean_. 115, C08014 (2010). * Weiss, R. F. Carbon dioxide in water and seawater: the solution of a non-ideal gas. _Mar. Chem._ 2, 203–215

(1974). Article CAS Google Scholar * Wanninkhof, R. Relationship between wind speed and gas exchange over the ocean. _J. Geophys. Res._ 97, 7373–7382 (1992). Article ADS Google Scholar

* Wanninkhof, R. Relationship between wind speed and gas exchange over the ocean revisited. _Limnol. Ocean. Methods_ 12, 351–362 (2014). Article Google Scholar * NASA Goddard Space

Flight Center, Ocean Ecology Laboratory, Ocean Biology Processing Group. _Moderate-Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) Aqua Chlorophyll Data; 2018 Reprocessing._ NASA OB.DAAC,

Greenbelt, MD, USA https://doi.org/10.5067/AQUA/MODIS/L3M/CHL/2018 (2018). * Jackson, T., Sathyendranath, S. & Platt, T. An exact solution for modeling photoacclimation of the

carbon-to-chlorophyll ratio in phytoplankton. _Front. Mar. Sci._ 4, 283 (2017). Article Google Scholar Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Data reported in this work were collected under

the auspices of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)’s Global Carbon Cycle (GCC) and Ocean Acidification Programs (OAP). We thank captains and crew of all vessels

involved in collecting the data at sea and the outstanding technical staff, students, postdocs, and PIs at NOAA and partner labs for their collaboration on the first decade of NOAA ocean

acidification cruises. The Canadian data were collected with support from NSF and Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO) Aquatic Climate Change Adaptation Services Program (ACCASP). We are

grateful to the governments of Canada and the United Mexican States for fishing licenses and research permission allowing us to conduct our research within their Exclusive Economic Zones

during all cruises (PPFE/DGOPA-072/16, PPFE/DGOPA-137/17, EG0082017, EG00032016, No. 343609, and IDR-1279). W.-J. C was also supported by NSF (grant no OCE-1559279). B.J. was supported by

Simons Foundation via grant no 549947 (SS). This is contribution number 4853 from the NOAA Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory. AUTHOR INFORMATION AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * School of

Marine Science and Policy, College of Earth, Ocean, and Environment, University of Delaware, 111 Robinson Hall, Newark, DE, 19716, USA Wei-Jun Cai, Yuan-Yuan Xu, Baoshan Chen, Najid Hussain,

Janet J. Reimer & Qian Li * NOAA Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory, 7600 Sand Point Way NE, Seattle, WA, 98115, USA Richard A. Feely, Simone R. Alin, Jessica N. Cross, Brendan R.

Carter & Adrienne J. Sutton * NOAA Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory, 4301 Rickenbacker Causeway, Miami, FL, 33149, USA Rik Wanninkhof & Leticia Barbero * Plymouth

Marine Laboratory, Prospect Place, Plymouth, PL1 3DH, UK Bror Jönsson * Cooperative Institute for Marine & Atmospheric Studies, University of Miami, 4600 Rickenbacker Causeway, Miami,

FL, 33149, USA Leticia Barbero * Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Bedford Institute of Oceanography, 1 Challenger Drive, Dartmouth, NS, B2Y 4A2, Canada Kumiko Azetsu-Scott * Monterey Bay

Aquarium Research Institute, 7700 Sandholdt Road, Moss Landing, CA, 95039, USA Andrea J. Fassbender * Joint Institute for the Study of the Atmosphere and Ocean, University of Washington,

3737 Brooklyn Avenue NE, Seattle, WA, 98195, USA Brendan R. Carter * Earth System Science Interdisciplinary Center, University of Maryland, College Park, MD, 20740, USA Li-Qing Jiang *

Department of Fisheries and Oceans, Northwest Atlantic Fisheries Centre, St. John’s, NL, Canada Pierre Pepin * First Institute of Oceanography, Ministry of Natural Resources, 266061,

Qingdao, China Liang Xue * Ocean Process Analysis Laboratory, University of New Hampshire, Durham, NH, 03824, USA Joseph E. Salisbury * Instituto de Investigaciones Oceanológicas,

Universidad Autónoma de Baja California, Ensenada, Baja California, Mexico José Martín Hernández-Ayón * Department of Marine Biology and Ecology, University of Miami, 4600 Rickenbacker

Causeway, Miami, FL, 33149, USA Chris Langdon * Department of Oceanography, National Sun Yat-sen University, Kaohsiung, 80424, Taiwan, ROC Chen-Tung A. Chen * NOAA Ocean Acidification

Program, 1315 East-West Highway, Silver Spring, MD, 20910, USA Dwight K. Gledhill Authors * Wei-Jun Cai View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar *

Yuan-Yuan Xu View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Richard A. Feely View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed

Google Scholar * Rik Wanninkhof View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Bror Jönsson View author publications You can also search for this

author inPubMed Google Scholar * Simone R. Alin View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Leticia Barbero View author publications You can also

search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Jessica N. Cross View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Kumiko Azetsu-Scott View author

publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Andrea J. Fassbender View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Brendan

R. Carter View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Li-Qing Jiang View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google

Scholar * Pierre Pepin View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Baoshan Chen View author publications You can also search for this author

inPubMed Google Scholar * Najid Hussain View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Janet J. Reimer View author publications You can also search

for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Liang Xue View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Joseph E. Salisbury View author publications You

can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * José Martín Hernández-Ayón View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Chris Langdon View

author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Qian Li View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Adrienne J.

Sutton View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Chen-Tung A. Chen View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google

Scholar * Dwight K. Gledhill View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CONTRIBUTIONS R.A.F. and S.R.A. are responsible for the design of the West

Coast Ocean Acidification (WCOA) cruises. J.C. is responsible for the design of the Gulf of Alaska Coast Ocean Acidification cruises. J.E.S., W.-J.C., and R.W. are responsible for the design

of the East Coast Ocean Acidification (ECOA) cruises. R.W. and L.B. are responsible for the design of the Gulf of Mexico Ecosystem and Carbon Cycle (GOMECC) cruises. K.A.-S. and P.P. are

responsible for the Davis Strait work. J.M.H.-A. is response for the Mexican Pacific coastal data. L.-Q.J. compiled the initial list of cruise data. J.J.R., B.C., N.H., Q.L. and C.L.

contributed to data collection efforts. Y.-Y.X. and W.-J.C. analyzed data. W.-J.C. prepared the paper. B.J. did the box-model simulation. L.X. and W.-J.C. did the temperature effect model.

A.J.F., S.R.A., B.R.C., R.W., R.A.F., B.J., A.J.S., C.-T.A.C., and D.K.G. edited the paper. All authors contributed to the discussion and writing. CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to

Wei-Jun Cai. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS The authors declare no competing interests. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION PEER REVIEW INFORMATION _Nature Communication_ thanks Marta Álvarez,

Adam Subhas, and other, anonymous, reviewers for their contributions to the peer review of this work. Peer review reports are available. PUBLISHER’S NOTE Springer Nature remains neutral with

regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION FINAL SI KRF PEER REVIEW FILE RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS OPEN ACCESS This article is

licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give

appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in

this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative

Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a

copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Cai, WJ., Xu, YY., Feely, R.A. _et al._ Controls on

surface water carbonate chemistry along North American ocean margins. _Nat Commun_ 11, 2691 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-16530-z Download citation * Received: 20 July 2019 *

Accepted: 23 March 2020 * Published: 01 June 2020 * DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-16530-z SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this

content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative