Play all audios:

ABSTRACT The latest coronavirus pandemic (SARS-CoV-2) poses an exceptional threat to human health and society worldwide. The coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) spike (S) protein, which is required for

viral–host cell penetration, might be considered a promising and suitable target for treatment. In this study, we utilized the nonalkaloid fraction of the medicinal plant _Rhazya stricta_

to computationally investigate its antiviral activity against SARS-CoV-2. Molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulations were the main tools used to examine the binding interactions of

the compounds isolated by HPLC analysis. Ceftazidime was utilized as a reference control, which showed high potency against the SARS-CoV-2 receptor binding domain (RBD) in an in vitro

study. The five compounds (CID:1, CID:2, CID:3, CID:4, and CID:5) exhibited remarkable binding affinities (CID:1, − 8.9; CID:2, − 8.7; and CID:3, 4, and 5, − 8.5 kcal/mol) compared to the

control compound (− 6.2 kcal/mol). MD simulations over a period of 200 ns further corroborated that certain interactions occurred with the five compounds and the nonalkaloidal compounds

retained their positions within the RBD active site. CID:2, CID:4, and CID:5 demonstrated high stability and less variance, while CID:1 and CID:3 were less stable than ceftazidime. The

average number of hydrogen bonds formed per timeframe by CID:1, CID:2, CID:3, and CID:5 (0.914, 0.451, 1.566, and 1.755, respectively) were greater than that formed by ceftazidime (0.317).

The total binding free energy calculations revealed that the five compounds interacted more strongly within RBD residues (CID:1 = − 68.8, CID:2 = − 71.6, CID:3 = − 74.9, CID:4 = − 75.4,

CID:5 = − 60.9 kJ/mol) than ceftazidime (− 34.5 kJ/mol). The drug-like properties of the selected compounds were relatively similar to those of ceftazidime, and the toxicity predictions

categorized these compounds into less toxic classes. Structural similarity and functional group analyses suggested that the presence of more H-acceptor atoms, electronegative atoms, acidic

oxygen groups, and nitrogen atoms in amide or aromatic groups were common among the compounds with the lowest binding affinities. In conclusion, this in silico work predicts for the first

time the potential of using five _R. stricta_ nonalkaloid compounds as a treatment strategy to control SARS-CoV-2 viral entry. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS IDENTIFICATION OF

ANTIVIRAL PHYTOCHEMICALS AS A POTENTIAL SARS-COV-2 MAIN PROTEASE (MPRO) INHIBITOR USING DOCKING AND MOLECULAR DYNAMICS SIMULATIONS Article Open access 13 October 2021 DEVELOPMENT OF

OPTIMIZED DRUG-LIKE SMALL MOLECULE INHIBITORS OF THE SARS-COV-2 3CL PROTEASE FOR TREATMENT OF COVID-19 Article Open access 07 April 2022 (+)-USNIC ACID AND ITS SALTS, INHIBITORS OF

SARS‐COV‐2, IDENTIFIED BY USING IN SILICO METHODS AND IN VITRO ASSAY Article Open access 30 July 2022 INTRODUCTION Coronavirus (COVID-19) infection is an acute respiratory tract illness

induced by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). It was initially reported in Wuhan, China, in December 20191. Following its onset, a pandemic of SARS-CoV-2 infection

caused disturbances to everyday life and economic activity, and great attempts have been made worldwide to develop effective treatments and vaccines to counteract the pandemic. Notably, the

mortality rate of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is higher among individuals with obesity and diabetes mellitus and those of older age2. Despite the high mortality and morbidity rates

associated with COVID-19 infection, no specific therapy is available and the majority of treatment interventions, such as ceftazidime which is used as empirical antibiotic therapy for

secondary bacterial infections, are supportive, appear to exert antiviral effect, and based on treating symptoms3. According to recent studies, third-generation cephalosporin antibiotics

have addressed potent compounds that block the interaction between spike protein and ACE2 by showing their high IC50 values, which support the idea of utilizing ceftazidime as an anti-SARS

CoV-2. Nevertheless, most drugs that have been used extensively for the treatment of COVID-19 were repurposing therapeutic candidate drugs, only focusing on a few classic viral sites4,5. The

angiotensin-converting enzyme-2 (ACE2) is a transmembrane protein, which is a receptor of the coronavirus' spike protein binding (SARS-CoV2). The distant S1 subunit of the SARS-CoV-2

spike glycoprotein contains the receptor binding domain and is essential to the membrane prefusion state. This glycoprotein is the primary target of antibody neutralization during infection

and also the target of treatment and vaccine designs6. Earlier viral epidemics, such as SARS and MERS, demonstrated the efficacy of targeting viral entry pathways as a therapeutic strategy7.

On the one hand, entry inhibitors impede viral transmission between persons; thus, they can be utilized therapeutically and prophylactically. On the other hand, they could be less toxic

since they prevent the virus from invading host cells in the first place3. Interest is growing nowadays toward assaying for phytochemicals as natural antivirals. Plants provide us with a

range of medicinal compounds that may limit viral reproduction by modulating viral adsorption, attaching to cell surface receptors, preventing virus penetration through the cell membrane,

and competing for intracellular signaling pathways. Polyphenols, alkaloids, flavonoids, saponins, quinones, terpenes, proanthocyanidins, lignins, tannins, polysaccharides, steroids,

thiosulfonates, and coumarins are all examples of bioactive phytochemicals that have been shown to be effective against viral infections8. _Rhazya stricta_ has traditionally been used to

treat a variety of illnesses in a wide range of Middle Eastern and South Asian nations_. R. stricta_ is known to be a rich source of several potent compounds, including nonalkaloids and

alkaloids, which have medicinal applications to treat a variety of conditions, including diabetes, inflammatory diseases, sore throat, helminthiasis, arthritis, infectious diseases, and

cancer, and several studies have previously confirmed its folkloric use9. Many of these medicinal properties have been validated experimentally by several investigations. Previous studies

have proved the antibacterial activities of nonalkaloid extracts derived from _R. stricta_ leaves against multi-drug-resistant (MDR) and Extended-spectrum beta-lactamases (ESBLs) bacteria,

which make it a drug candidate against several pathogens10. The novel natural drug discovery may recognize the new molecular entities that will help even more against variants of SARS-CoV-2.

In the present study, we characterized the _R. stricta_ extract using HPLC–MS/MS analysis and conducted a computational study to target the SARS-CoV-2 RBD protein. In addition, molecular

docking, dynamic simulations, binding free energy calculations, and ligand bioavailability were performed to determine potential inhibitors. Moreover, we study the structural skeleton

similarity of the best-docked compounds to assign their Physicochemical properties. MATERIALS AND METHODS COLLECTION AND PREPARATION OF PLANT SAMPLES _Rhazya stricta_ was collected from its

natural habitat in the desert; in the Al Gholah region near Asfan Road (21.9684537, 39.2675785), Jeddah Province. A voucher specimen was deposited in the Department of Biological Sciences

Herbarium at King Abdulaziz University (number 1150/M/75; collected by N. Baeshen, M. Baeshen, and J. Sabir). The plant material was taken to the laboratory, and the leaves were cut and

washed with running water to remove the dust and left to dry in the laboratory at room temperature. A week later, the dry leaves were ground into a fine powder for the extraction of

compounds and biochemical analysis. The authors confirm that the experiments performed on the plants in the present study comply with international and national guidelines. Alkaloids and

nonalkaloids were extracted from _R. stricta_ as described by10. In brief, ten grams of plant material was weighed into a clean volumetric flask, and 20 ml of absolute ethanol (99%) was

added. The mixture was allowed to sit in a refrigerator (4 °C) for two days. The ethanol was removed by placing the mixture over Whatman filter paper (0.45 µm) and drying the plant material

with nitrogen gas. After that, 5 g of plant material was transferred to a clean volumetric flask, and 40 ml of 1 mol/L HCl and 40 ml of HPLC-grade chloroform were added. The chloroform layer

was collected and filtered through a PTFE disk filter and then transferred to an LC vial to analyze the nonalkaloids. For the alkaloids, sodium hydroxide was added to the plant mixture to

adjust the pH, and then 40 ml of HPLC-grade chloroform was added. The chloroform layer, which contained the alkaloids, was filtered through a PTFE disk filter and transferred to a liquid

chromatography vial for analysis. HPLC–MS/MS ANALYSIS AND DATA PROCESSING This study was performed using an HPLC–MS/MS system that included an ACQUITY UPLC I-Class (Waters Technologies, USA)

instrument coupled to a 6500 Qtrap (AB Sciex, Canada). Chromatographic separation was performed using a Zorbax XDB C18 column (2.1 × 150 mm, 3.5 µm) with a temperature maintained at 40 °C,

a flow rate of 300 µL/min and an injection volume of 10 µL. Solvents A (0.1% formic acid in HPLC grade water) and B (0.1% formic acid in HPLC grade acetonitrile) were used as the mobile

phases. The linear elution gradient was as follows: 2% B (from 0 to 2), 95% B (from 2 to 24), 95% B (held for 2 min), and 4 min of equilibration. The electrospray ionization mass

spectrometry (ESI–MS) data were collected in positive mode (ES+) with an electrode voltage of 5500 V, a declustering potential (DP) of 90 V, collision energy of 30 V, and an input potential

of 10 V. Nitrogen was used as the nebulizer gas and curtain gas at 30 psi. Mass spectrometry (MS) spectra were acquired in the mass range of 100–900 m/z, and a scan rate of 1000 was used to

search for enhanced production. For MS–MS data collection, the acquisition rate was set to 1 spectrum per second with a scan range of 50–1000 m/z in automode according to11. Upon completion

of data collection, the HPLC–MS data files were downloaded in wiff format and then converted to Mzml using MSConvert (ProteoWizard 3.0.20270)12. Mzmine (version 2.53) software was used to

analyze the results13 (https://github.com/mzmine/mzmine2/releases/tag/v2.53). Following data import into Mzmine2, a minimum intensity cutoff of 1,000 was used, and the retention time was set

to a tolerance of 0.2 min. Then, the adjusted peaks were compiled into a single mass list to enable detection and comparison. The identification process was performed using the SIRIUS

platform coupled with CSI:FingerID for molecular structure identification14,15,16. LIGANDS AND PROTEIN PREPARATION Hundreds of nonalkaloid compounds were identified in _R. stricta_ by HPLC

and MS/MS analyses. The structures of the _R. stricta_ nonalkaloid compounds were discovered through HPLC analysis, downloaded from the PubChem database (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/)

as SDF files, and then converted into PDB files using PyMOL (Schrödinger, LLC)17,18. The AutoDock 4.2 graphical interface19 was used to prepare the ligands by adding the computed Gasteiger

charge and merging the nonpolar hydrogen atoms. Aromatic carbon rings were also detected to set up a torsion tree. The compound files were saved in pdbqt format for further screening. The

crystal structure of the SARS-CoV-2 spike receptor-binding domain (RBD) complexed with ACE2 was retrieved from the RCSB (https://www.rcsb.org) with PDB ID 6m0j21, consisting of 193 amino

acids for the RBD and 596 amino acids for ACE2 with a resolution of 2.45 Å. The RBD was prepared by deleting the ACE2 atom coordinates and removing ligands, water, and ionic metals from the

complex structure. Nonpolar hydrogen atoms were merged, and Kollman charges were added to the RBD. The prepared protein was saved as a pdbqt file. VIRTUAL SCREENING AutoDock Vina is an

open-source program that predicts the binding positions of small molecules into the cavity of interest of a target protein in addition to the small molecule binding affinities22. The grid

box was concentrated with dimensions (50X, 64Y, 22Z) and a grid point of 0.375 Å on the interface of the RBD, which contains the involved residues in connection with the ACE2 receptor (K417,

G446, Y449, Y453, L455, F456, A475, F486, N487, Y489, Q493, G496, Q498, T500, N501, G502, Y505). AutoDock Vina was run using an in-house Python script, which prompted the system to the

configuration file containing the screening parameters. We set the exhaustiveness of the search to 8, and 9 conformation modes were generated for each compound. MOLECULAR DOCKING The

best-docked compounds (~ 60), which had the lowest binding affinities and RMSD values of 0 Å into the RBD interface, were subjected to analysis by ACD/ChemSketch to check for tautomeric

forms23. Geometry optimization was also conducted using Avogadro software, which has an auto-optimization tool24. Structure optimization and energy minimization were performed by the

universal force field (UFF) and the steepest descent algorithm. To find accurate conformations and positions, we redocked the ligand–protein complexes using AutoDock Vina with the grid box

dimensions listed above the exhaustiveness of the search set to 30. Finally, we concentrated the grid box on the lowest binding affinity position of the best 5 compounds and redocked the

complexes. To compare our results with those of a drug that has been confirmed to show in vitro anti-SARS-CoV-2 spike protein activity, we found that the antibiotic ceftazidime, which is

used therapeutically to treat bacterial pneumonia, revealed the highest potency among several compounds, with an inhibition rate of approximately 80% and an IC50 of 28 µM25. Biovia Discovery

Studio Visualizer was used to plot the compounds into the pocket residues and PyMOL17,26. MOLECULAR DYNAMICS SIMULATIONS MD simulations were performed using the Groningen Machine for

Chemical Simulations (GROMACS) 2020.327. The procedure was conducted as described28. To create the structural topology, the compound-protein complex coordinates were separated into two PDB

files. The protein force field parameter was generated using the March 2019 version of Chemistry at Harvard Macromolecular Mechanics (CHARMM 36)29, whereas the ligand was converted to Mol

file format using Avogadro24, and the force field parameters were generated using the official CHARMM General Force Field server (CGenFF: 30. The system was contained within a dodecahedron

box with periodic boundary conditions. The box was then solvated using a three-site transferable water model (TIP3P)31, which was subsequently neutralized with Na and Cl ions. A 5,000-step

structural optimization using the steepest descent algorithm followed by a 100 ps equilibration in the NVT and NPT ensembles utilizing a V-rescale thermostat32 and a Berendsen barostat33 for

temperature and pressure coupling were carried out to minimize system energy. The van der Waals and electrostatic interaction cutoffs were fixed at 1.2 nm, and long-range electrostatic

interactions were calculated using the particle mesh Ewald method34. The temperature and pressure were maintained at 300 K and 1 bar for the production run. A V-rescale thermostat32 with a

time constant of 0.1 ps was used to regulate the temperature, while a Parrinello-Rahman barostat35 with a time constant of 1 ps and compressibility of 4.5 × 10–5 bar-1 was employed to the

control pressure. The simulation was run for 200 ns, and every 10 ps, the energy and coordinates of the trajectories were recorded. The stabilities of the resultant trajectories were then

analyzed using the root mean square deviation (RMSD), the root mean square fluctuation (RMSF), the hydrogen bond number, and the final trajectory. The plotting tool Xmgrace was utilized to

plot the simulation data36, and PyMOL was used to visualize the obtained trajectories17. BINDING ENERGY CALCULATIONS Binding free energy calculations for all docked complexes were conducted

using the Molecular Mechanics/Poisson-Boltzmann Surface Area (MM/PBSA) approach in the g_mmpbsa module. The g_mmpbsa scripts utilized were widely sourced from the GROMACS machine and APBS

packages to integrate the molecular dynamics simulation trajectories with the binding energy calculations. A total of 500 snapshots of the complex trajectories were obtained. Electrostatic

interactions, van der Waals interactions, polar salvation energy, and nonpolar solvation energy were calculated using the g_mmpbsa module37,38. DRUG-LIKENESS ANALYSIS To investigate the oral

bioavailability of the top 5 compounds, Lipinski's rule of five39 was applied, which considers the following parameters: molecular weight, lipophilicity, number of hydrogen bond

donors, and number of nitrogen and oxygen atoms. To predict the drug-likeness profile of the compounds with the lowest binding affinities from the docking results, the PDB files of the

compounds were submitted to SwissADME, which is a webserver that calculates the physiochemical properties of compounds and applies drug-likeness parameters40. Moreover, the results were

compared to the injectable antibiotic ceftazidime. TOXICITY RISK PREDICTION ProTox-II is a website that predicts the acute oral toxicities of small molecules and places them into classes

according to the globally harmonized system of classification and labelling of chemicals (GHS)41. Canonical Smiles of the compounds were obtained from the PubChem database and inputted into

the webserver. The compound toxicity classes and LD50 predictions were generated as output results. STRUCTURAL SKELETON SIMILARITY ANALYSIS To find the common structural skeleton similarity

of the compounds of interest, we utilized DataWarrior software, which is a multipurpose chemical data visualization and analysis tool that is interactive and chemistry-aware42. Forty

compounds with a 7.1 (kcal/mol) binding affinity cutoff were submitted to DataWarrior for structure analysis. We counted and analyzed the presence of 8 structural parameters: aromatic carbon

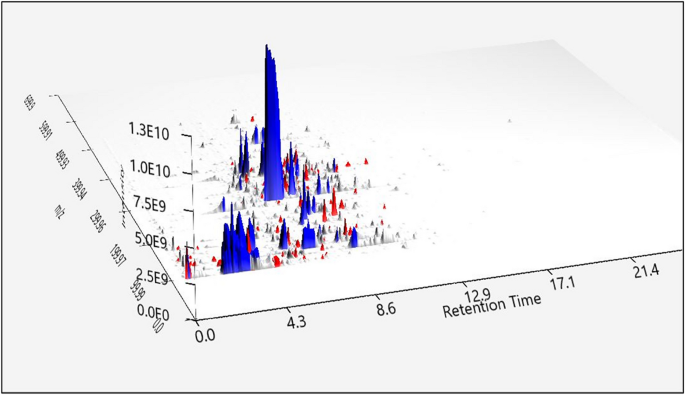

atoms, carbo rings, electronegative atoms, H-acceptor atoms, H-donor atoms, heterorings, ring closures, and rotatable bonds. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION HPLC–MS/MS ANALYSIS The nonalkaloids from

_R. stricta_ were isolated using HPLC. Separation using HPLC confirmed the existence of nine nonalkaloid compounds and seven additional alkaloids as minor components (Fig. 1). VIRTUAL

SCREENING AND MOLECULAR DOCKING Virtual screening is a fast-scanning method that can dock a library of ligands into the active site of the protein of interest and reduce the library by

eliminating those with the highest binding energies. In our study, after we screened the compounds obtained from the phytochemical analysis, the compounds with the lowest binding affinity

were optimized, redocked, and prepared for further analysis. The involved residues and number of bonds formed by the 5 best compounds (Table 1) and the compound control ceftazidime are

presented in Table 2. Compound CID:1 demonstrated a binding affinity of − 8.9 (kcal/mol) and formed six conventional hydrogen bonds with RBD interface residues ARG346, ASN448, LYS444,

GLN493, and SER494. In addition, four hydrophobic interactions were observed of the types pi—pi stacked, pi—alkyl, and alkyl in contact with PHE490, TYR449, and LYS444 residues. Compound

CID:2 showed a binding affinity of − 8.7 (kcal/mol) and formed seven hydrogen bonds with residues TYR449, GLN493, SER494, ARG403, and TYR453. Moreover, six hydrophobic interactions of the

types pi—pi stacked, pi—alkyl and alkyl involved with the SARS-CoV-2 RBD residues PHE490, LEU452, and LYS417. Compounds CID:3, CID:4, and CID:5 showed binding affinities of − 8.5 (kcal/mol)

with various numbers of hydrogen bonds and other interactions. Compound CID:3 formed six hydrogen bonds with the active site residues TYR449, GLN493, and GLY496. In addition, four

hydrophobic interactions of the types T-shaped pi-pi, amide pi-stacked, alkyl interactions with TYR449, TYR505, LEU452, and GLN493, and two halogen bonds with GLN493 and LEU492. Compound

CID:4 formed five hydrogen bonds with the RBD binding site residues GLN493, SER494, and GLY496 and six hydrophobic interactions of the types—pi–pi stacked, pi—alkyl, and alkyl with key

residues ARG403, TYR449, PHE497, TYR505, and TYR495. Compound CID:5 formed seven hydrogen bonds with residues ARG403, TYR453, GLY496, and GLN498 and seven hydrophobic interactions of the

types T-shaped pi–pi, pi—alkyl, and alkyl with residues TYR449, TYR505, LYS417, and LEU455. In addition, one pi – cation electrostatic interaction was formed with ARG403. CEFTAZIDIME was

considered a control, giving a binding affinition of − 6.2 (kcal/mol), and formed six conventional hydrogen bonds with residues ARG403, TYR453, GLY496, TYR449, and GLN498. In addition,

attractive electrostatic forces, one pi – alkyl interaction with residues ARG403 and TYR449, and hydrophobic interactions were involved in the ceftazidime-RBD interaction. In addition to the

mentioned contacts, the six compounds interacted with the interface residues by van Der Waals forces (Figs. 2 and 3). In addition to the reference compounds, the five compounds formed many

bonds with key residues LYS417, TYR453, TYR505, ASN501 GLN493, GLY496, TYR449, GLN498, and LEU455 of the SARS-CoV-2 RBD, which may interrupt the viral host cell recognition process. The 5

phytochemical compounds investigated through molecular docking simulations here revealed significantly better binding energy. In contrast to the reference compounds, these five compounds

established networks of hydrophobic interactions that contribute to the binding affinity of the predicted complexes. MD SIMULATIONS AND BINDING FREE ENERGY CALCULATIONS We further used

GROMACS 2020.3 to run MD simulations on the five RBD-ligand complexes as well as the control compound on a 200 ns time scale to investigate the dynamic binding interactions and calculate the

binding free energies. RMSD AND RMSF The root mean square deviation (RMSD) is a critical measure for analyzing the equilibration of MD trajectories and determining the stability of

protein–ligand complex systems during the simulation process. This value was calculated for each compound and compared to that of ceftazidime with respect to the initial pose as a reference

frame. All compounds retained their docking position with some deviation (Fig. 4). CEFTAZIDIME showed insignificant deviation (~ 0.18–0.27 nm) and high stability with rare major variance.

During the MD simulations, compounds CID:1 and CID:3 showed acceptable deviations (~ 0.28–0.4 and 0.2–0.35 nm, respectively) and stability with major variance in some frames. Compound CID:2

exhibited moderate deviations during the first and last 50 ns (~ 0.2–0.26 nm), and higher deviations between 50–150 ns (~ 0.3–0.4 nm) were observed. In addition, compound CID:2 showed high

stability in both poses, and no major variance was observed. Compound CID:4 showed insignificant deviation (~ 0.15–0.24 nm), high stability and no variance. Although compound CID:5 had a

high deviation (0.34–0.42 nm), it also had high stability with no undesired variance. To understand the behavior of the ligand atoms, the root mean square fluctuation (RMSF) during the MD

simulations of the 5 compounds and CEFTAZIDIME were analyzed. All compounds experienced a certain amount of fluctuation (Fig. 5), and the atoms of CID:4 fluctuated the least (~ 0.05–0.25 nm)

compared with the atoms of the other compounds, indicating that CID:4 did not undergo major conformational changes. The atoms of CEFTAZIDIME, CID:2, and CID:3 fluctuated in the range of ~

0.1–0.35 nm. The RMSF of CID:1 and CID:5 reflected the RMSD results, as these two compounds were exposed to conformational changes (~ 0.15–0.55 and 0.1–0.45 nm, respectively). HYDROGEN BONDS

The number of hydrogen bonds that a compound forms with protein residues plays a critical role in enhancing complex stability. The cutoff angle and distance for H-bond analysis were set to

30° and 3.5 Å (Fig. 6). CEFTAZIDIME formed 1–7 hydrogen bonds, and the average of 0.317 hydrogen bonds per timeframe was calculated. CID:1 and CID:3 showed 1–5 hydrogen bonds bound to the

RBD with average numbers of hydrogen bonds per timeframe of 0.914 and 1.566, respectively. CID:2 and CID:4 formed 1–3 hydrogen bonds for averages of 0.451 and 0.149 hydrogen bonds per

timeframe, respectively. CID:5 had the highest number of hydrogens (1–8) that formed and an average of 1.755 hydrogen bonds per timeframe. TRAJECTORY The compound positions and the

interacting residues during the MD simulations were visualized by extracting the final frame. In addition to CEFTAZIDIME, the docked MD simulations poses of compounds CID:1 CID:2, CID:3,

CID:4, and CID:5 were nearly identical to the redocked poses with the exception of CID:3, which abandoned its polar interactions with ASN501 to TYR505. Notably, the resulting docked position

of CEFTAZIDIME was compatible with a previous investigation, which revealed that the residues SER494 and TYR505 play critical roles in the binding of SARS-CoV-2 to the hACE2 receptor23

(Fig. 7). BINDING ENERGY CALCULATIONS The MM-PBSA analyses were performed by extracting 500 snapshots of the stabilized frames for the 5 complexes as well as the control complex to calculate

the binding energy average. A highly negative binding energy indicates stable binding of a small molecule to a protein. Compared to the RBD-ceftazidime complex (− 34.495 kJ/mol), the

resulting binding free energies of the five ligand complexes gave values that were more negative, indicating that these 5 compounds established strong interactions. CID:4 showed the lowest

negative value (− 75.448), followed by compounds CID:3 (− 74.926 kJ/mol), CID:2 (− 71.579 kJ/mol), CID:1 (− 68.788 kJ/mol), and CID:5 (− 60.865 kJ/mol) (Table 3). The MMPBSA-based binding

energy values of the identified ligands toward the SARS-CoV-2 RBD reflect that each ligand binds efficiently. This conclusion is further supported by data from other parameters, such as the

RMSD, RMSF, number of HBs, and average number of HBs per frame calculated from the MD trajectories. DRUG-LIKENESS AND TOXICITY PREDICTIONS Drug-likeness predictions were conducted using

SwissADME to calculate the physiochemical properties and then applying Lipinski’s rule of five for comparison with CEFTAZIDIME, which is an injectable broad-spectrum antibiotic used to treat

bacterial infections including lower respiratory tract pneumonia43. Violation of the implemented parameters of Lipinski’s rule of five suggests increased absorption and permeation

difficulties if the compounds are administered orally39. All compounds as well as the control compounds violated the molecular weight parameter (662.18, 578.83, 643.88, 539.59, 676.55, and

546.6 g/mol for CID:1, CID:2, CID:3, CID:4, CID:5 and ceftazidime, respectively). In addition, the parameter for the number of H-bond acceptors was violated by the investigated compounds

with the exception of compound CID:2, which had 7 H-bond acceptor atoms (Table 4). In addition to the drug likeness predictions, drug toxicity was predicted using the ProTox-II webserver.

The quantities of each substance that resulted in death to 50% of the population (LD50) were determined and categorized according to the globally harmonized system of classification and

labelling of chemicals. The LD50 values of compounds CID:1, CID:2, and CID:4 (464, 705, and 1300 mg/kg, respectively) were predicted to belong to class 4 (300 < LD50 ≤ 2000). Compound

CID:3 showed less toxicity with an LD50 of 3016 mg/kg and was categorized into class 5 (2000 < LD50 ≤ 5000). CID:5 was labeled as nontoxic compound with an LD50 of 10,000 mg/kg, and

classified as class 6 (LD50 > 5000) (Table 5). These results suggest that the bioactive compounds CID:1, CID:2, CID:3, CID:4, and CID:5 have lower gastrointestinal absorption properties

compared with ceftazidime. In contrast to CID:5 and ceftazidime, which were predicted to be nontoxic substances, CID:1 and CID:2 may possess toxicity risks, and CID:4 and CID:3 are

associated with less risk. STRUCTURAL SKELETON SIMILARITY ANALYSIS The 40 compounds that gave best binding affinities were submitted to DataWarrior software analysis, which was utilized to

count and categorize 8 structural skeleton parameters and investigate their similarities (Fig. 8). To define the flexibility of the compounds, we counted the number of intramolecular

rotatable bonds and found that 29 of the compounds were composed of 5–9 rotatable bonds, including 7 out of the best 10 compounds. Electronegative atoms (N, O, S, F, Cl) within small

molecules play critical roles in forming hydrogen bonds with protein residues; at least 7 of these atoms were counted in CID:16, and 28 compounds had 11–15 electronegative atoms. To

determine the form of the electronegative atoms, we counted the number of H-bond donors and H-bond acceptors. Twenty-eight compounds contained 2–4 H-donor atoms, including 7 of the best

docked compounds. In contrast, at least 4 H-acceptor atoms were counted in CID:27, and 28 compounds, including 7 of the best docked compounds, contained 9–13 H-acceptor atoms. Ring closures,

which are mostly composed of carbon atoms involved in hydrophobic and electrostatic interactions, were counted, and we found 33 compounds containing 4 or 5 rings, including the best 9

compounds. To determine the form of the ring closures, we counted both carbo- and heteroring closures. Among the carbo rings, we found 29 compounds containing 1–2 rings. In contrast to the

carborings, 33 compounds contained 2–4 heterorings, including 7 of the best 10 compounds. Finally, we counted the number of aromatic carbon atoms, and the 40 compounds were distributed among

15 categories. Twenty-seven compounds were in the range of 17–27 aromatic atoms, including 8 of the ten best compounds. After we characterized and analyzed the 40 compounds that gave an

affinity binding score of − 7.1 (kcal/mol) or less, we found no direct or inverse relationship between the parameters that we investigated and the binding affinities of the compounds. In

addition, the desired range and cutoff of some of the parameter combinations could lead to an increase in the binding affinity of small molecules to the SARS-CoV-2 RBD, such as at least 7

electronegative atoms, 5–9 rotatable bonds, 4–2 H-donor atoms, at least 7 H-acceptor atoms, 1–3 carbo rings, and 2–4 hetero rings. CONCLUSION Our study aimed to find a prospective drug

against SARS-CoV-2 and examine the similarities among the investigated compounds by utilizing compounds derived from the medicinal plant _R. stricta_. Applying a virtual screened approach,

we identified five compounds from _the R. stricta nonalkaloid extract._ In comparison to the reference control (ceftazidime), the lead compounds exhibited remarkable binding affinities and

strong interactions with key residues of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. The findings of this in silico study suggest that these compounds can be considered potential antiviral drugs to treat

SARS-CoV-2 by interfering with the viral ACE2 recognition process. However, more experimental validation is required to confirm the antiviral activity of the selected compounds against the

SARS-CoV-2 RBD. The two main outcomes from the structural skeleton analysis could help researchers design or narrow their search to find bioactive compounds targeting the SARS-CoV-2 RBD:

electronegative atoms are preferable in the H-acceptor form, and ring closures are preferable in heteroatom form. However, a large compound population and more structural skeleton parameter

analyses are required to reveal more recommended characteristics and confirm our findings. REFERENCES * Surveillances, V. The epidemiological characteristics of an outbreak of 2019 novel

coronavirus diseases (COVID-19)—China, 2020. _China CDC Weekly_ 2(8), 113–122 (2020). Article Google Scholar * Wu, Z. & McGoogan, J. M. Characteristics of and important lessons from

the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: Summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. _JAMA_ 323(13), 1239–1242 (2020).

Article CAS Google Scholar * Seyedpour, S. _et al._ Targeted therapy strategies against SARS-CoV-2 cell entry mechanisms: A systematic review of in vitro and in vivo studies. _J. Cell.

Physiol._ 236(4), 2364–2392 (2021). Article CAS Google Scholar * Eid, R. A. _et al._ Efficacy of ceftazidime and cefepime in the management of COVID-19 patients: Single center report from

Egypt. _Antibiotics_ 10(11), 1278 (2021). Article CAS Google Scholar * Chan, W. K. _et al._ In silico analysis of SARS-CoV-2 proteins as targets for clinically available drugs. _Sci.

Rep._ 12(1), 1–12 (2022). Article Google Scholar * Walls, A. C. _et al._ Structure, function, and antigenicity of the SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein. _Cell_ 181(2), 281–292 (2020). Article

CAS Google Scholar * Xia, S. _et al._ Inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 (previously 2019-nCoV) infection by a highly potent pan-coronavirus fusion inhibitor targeting its spike protein that

harbors a high capacity to mediate membrane fusion. _Cell Res._ 30(4), 343–355 (2020). Article CAS Google Scholar * Kapoor, R., Sharma, B. & Kanwar, S. S. Antiviral phytochemicals: An

overview. _Biochem. Physiol._ 6(2), 7 (2017). Article Google Scholar * Baeshen, M. N., Khan, R., Bora, R. S., & Baeshen, N. A. (2015). Therapeutic potential of the folkloric medicinal

plant Rhazya stricta. Biol Syst Open Access, 5(2). * Khan, R. _et al._ Antibacterial activities of Rhazya stricta leaf extracts against multidrug-resistant human pathogens. _Biotechnol.

Biotechnol. Equip._ 30(5), 1016–1025 (2016). Article CAS Google Scholar * Rawle, R.A., et al., Metabolic responses to arsenite exposure regulated through histidine kinases PhoR and AioS

in. Microorganisms, 2020. 8(9). * Chambers, M. C. _et al._ A cross-platform toolkit for mass spectrometry and proteomics. _Nat Biotechnol_ 30(10), 918–920 (2012). Article CAS Google

Scholar * Pluskal, T. _et al._ MZmine 2: Modular framework for processing, visualizing, and analyzing mass spectrometry-based molecular profile data. _BMC Bioinformat._ 11, 395 (2010).

Article Google Scholar * Dührkop, K. _et al._ SIRIUS 4: A rapid tool for turning tandem mass spectra into metabolite structure information. _Nat Methods_ 16(4), 299–302 (2019). Article

Google Scholar * Dührkop, K. _et al._ Searching molecular structure databases with tandem mass spectra using CSI:FingerID. _Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA_ 112(41), 12580–12585 (2015). Article

ADS Google Scholar * Ludwig, M. _et al._ Database-independent molecular formula annotation using Gibbs sampling through ZODIAC. _Nat. Mach. Intell._ 2(10), 629–641 (2020). Article

Google Scholar * https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/. * The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 2.4.1 Schrödinger, LLC. * Morris, G. M. _et al._ Autodock4 and AutoDockTools4: Automated

docking with selective receptor flexiblity. _J. Comput. Chem._ 16, 2785–2791 (2009). Article Google Scholar * https://www.rcsb.org. * Lan, J. _et al._ Structure of the SARS-CoV-2 spike

receptor-binding domain bound to the ACE2 receptor. _Nature_ 581(7807), 215–220 (2020). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Trott, O. & Olson, A. J. AutoDock Vina: Improving the speed

and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. _J. Comput. Chem._ 31(2), 455–461 (2010). CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar *

ACD/ChemSketch, version 2021.1.1, Advanced Chemistry Development, Inc., Toronto, ON, Canada. www.acdlabs.com, 2021. * Hanwell, M. D. _et al._ Avogadro: An advanced semantic chemical editor,

visualization, and analysis platform. _J. Cheminf._ 4(1), 1–17 (2012). Article Google Scholar * Lin, C. _et al._ Ceftazidime is a potential drug to inhibit SARS-CoV-2 infection in vitro by

blocking spike protein–ACE2 interaction. _Signal Transduct. Target. Ther._ 6(1), 1–4 (2021). Google Scholar * BIOVIA, Dassault Systèmes, [Discovery Studio], [21.1.0], San Diego: Dassault

Systèmes, [2021]. * Abraham, M. J. _et al._ GROMACS: High performance molecular simulations through multi-level parallelism from laptops to supercomputers. _SoftwareX_ 1, 19–25 (2015).

Article ADS Google Scholar * Lemkul, J. From proteins to perturbed Hamiltonians: A suite of tutorials for the GROMACS-2018 molecular simulation package [article v1. 0]. _Living J. Comput.

Mol. Sci._ 1, 5068 (2018). Google Scholar * Huang, J. & MacKerell, A. D. Jr. CHARMM36 all-atom additive protein force field: Validation based on comparison to NMR data. _J. Comput.

Chem._ 34(25), 2135–2145 (2013). Article CAS Google Scholar * Vanommeslaeghe, K. _et al._ CHARMM general force field: A force field for drug-like molecules compatible with the CHARMM

all-atom additive biological force fields. _J. Comput. Chem._ 31(4), 671–690 (2010). CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Jorgensen, W. L., Chandrasekhar, J., Madura, J. D., Impey,

R. W. & Klein, M. L. Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water. _J. Chem. Phys._ 79(2), 926–935 (1983). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Bussi, G.,

Donadio, D. & Parrinello, M. Canonical sampling through velocity rescaling. _J. Chem. Phys._ 126(1), 014101 (2007). Article ADS Google Scholar * Berendsen, H. J., Postma, J. V., van

Gunsteren, W. F., DiNola, A. R. H. J. & Haak, J. R. Molecular dynamics with coupling to an external bath. _J. Chem. Phys._ 81(8), 3684–3690 (1984). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar *

Essmann, U. _et al._ A smooth particle mesh Ewald method. _J. Chem. Phys._ 103(19), 8577–8593 (1995). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Parrinello, M. & Rahman, A. Polymorphic

transitions in single crystals: A new molecular dynamics method. _J. Appl. Phys._ 52(12), 7182–7190 (1981). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Vaught, A. Graphing with Gnuplot and Xmgr:

Two graphing packages available under linux. _Linux J._ 1996(28es), 7-es (1996). Google Scholar * Baker, N. A., Sept, D., Joseph, S., Holst, M. J. & McCammon, J. A. Electrostatics of

nanosystems: application to microtubules and the ribosome. _Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci._ 98(18), 10037–10041 (2001). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Kumari, R., Kumar, R., Lynn, A., Open

Source Drug Discovery Consortium. g_mmpbsa: A GROMACS tool for high-throughput MM-PBSA calculations. _J. Chem. Inf. Model._ 54(7), 1951–1962 (2014). Article CAS Google Scholar * Lipinski,

C. A., Lombardo, F., Dominy, B. W. & Feeney, P. J. Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings. _Adv.

Drug Deliv. Rev._ 23(1–3), 3–25 (1997). Article CAS Google Scholar * Daina, A., Michielin, O. & Zoete, V. SwissADME: A free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness and

medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules. _Sci. Rep._ 7(1), 1–13 (2017). Article Google Scholar * Banerjee, P., Eckert, A. O., Schrey, A. K. & Preissner, R. ProTox-II: A

webserver for the prediction of toxicity of chemicals. _Nucleic Acids Res._ 46(W1), W257–W263 (2018). Article CAS Google Scholar * Sander, T., Freyss, J., von Korff, M. & Rufener, C.

DataWarrior: An open-source program for chemistry aware data visualization and analysis. _J. Chem. Inf. Model._ 55(2), 460–473 (2015). Article CAS Google Scholar *

https://go.drugbank.com/drugs/DB00438 Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This project was funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research (DSR) at King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, under

Grant No. GCV19-29-1441. The authors therefore thank the DSR for financial support. AUTHOR INFORMATION AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Department of Biological Sciences, Faculty of Science, King

Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia Nabih A. Baeshen, Abdulaziz O. Albeshri, Thamer A. Bouback & Abdullah A. Aljaddawi * Department of Biology, College of Sciences and Arts,

University of Jeddah, Khulais Campus, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia Naseebh N. Baeshen * Department of Biology, College of Science, University of Jeddah, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia Roba Attar, Alaa

Karkashan, Basma Abbas, Hayam S. Abdelkader & Mohammed N. Baeshen * Department of Biochemistry, College of Science, University of Jeddah, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia Mohammed Y. Refai &

Firoz Ahmed * Reference Laboratory for Food Chemistry, Saudi Food & Drug Authority (SFDA), Riyadh, Saudi Arabia Abdullah Al Tamim & Abdullah Alowaifeer Authors * Nabih A. Baeshen

View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Abdulaziz O. Albeshri View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google

Scholar * Naseebh N. Baeshen View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Roba Attar View author publications You can also search for this author

inPubMed Google Scholar * Alaa Karkashan View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Basma Abbas View author publications You can also search for

this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Thamer A. Bouback View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Abdullah A. Aljaddawi View author publications

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Mohammed Y. Refai View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Hayam S. Abdelkader

View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Abdullah Al Tamim View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar

* Abdullah Alowaifeer View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Firoz Ahmed View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed

Google Scholar * Mohammed N. Baeshen View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CONTRIBUTIONS N.A.B., N.N.B., A.A.J. and M.N.B. designed and wrote

the project. A.O.A. conducted the in silico and MD stimulation analyses. F.A. analyzed the data and revised the manuscript. M.N.B., T.A. B., R.A., A.K. and B.A. collected the plant material

and performed the plant experiments. H.S.A., N.N.B. and A.O.A. wrote as well as reviewed the manuscript. CORRESPONDING AUTHORS Correspondence to Naseebh N. Baeshen or Mohammed N. Baeshen.

ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS The authors declare no competing interests. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION PUBLISHER'S NOTE Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional

claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION. RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS OPEN ACCESS This article is licensed under a Creative

Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the

original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in

the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your

intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence,

visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Baeshen, N.A., Albeshri, A.O., Baeshen, N.N. _et al._ In silico screening of

some compounds derived from the desert medicinal plant _Rhazya stricta_ for the potential treatment of COVID-19. _Sci Rep_ 12, 11120 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-15288-2

Download citation * Received: 23 June 2021 * Accepted: 22 June 2022 * Published: 01 July 2022 * DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-15288-2 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the

following link with will be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer

Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative