Play all audios:

Over the course of the 20th century, capitalism preserved its momentum by molding the ordinary person into a consumer with an unquenchable thirst for more stuff. By: Kerryn Higgs Listen to

this article Brought to you by Curio, an MIT Press partner The notion of human beings as consumers first took shape before World War I, but became commonplace in America in the 1920s.

Consumption is now frequently seen as our principal role in the world. People, of course, have always “consumed” the necessities of life — food, shelter, clothing — and have always had to

work to get them or have others work for them, but there was little economic motive for increased consumption among the mass of people before the 20th century. Quite the reverse: Frugality

and thrift were more appropriate to situations where survival rations were not guaranteed. Attempts to promote new fashions, harness the “propulsive power of envy,” and boost sales

multiplied in Britain in the late 18th century. Here began the “slow unleashing of the acquisitive instincts,” write historians Neil McKendrick, John Brewer, and J.H. Plumb in their

influential book on the commercialization of 18th-century England, when the pursuit of opulence and display first extended beyond the very rich. But, while poorer people might have acquired

a very few useful household items — a skillet, perhaps, or an iron pot — the sumptuous clothing, furniture, and pottery of the era were still confined to a very small population. In late

19th-century Britain a variety of foods became accessible to the average person, who would previously have lived on bread and potatoes — consumption beyond mere subsistence. This improvement

in food variety did not extend durable items to the mass of people, however. The proliferating shops and department stores of that period served only a restricted population of urban

middle-class people in Europe, but the display of tempting products in shops in daily public view was greatly extended — and display was a key element in the fostering of fashion and envy.

Although the period after World War II is often identified as the beginning of the immense eruption of consumption across the industrialized world, the historian William Leach locates its

roots in the United States around the turn of the century. In the United States, existing shops were rapidly extended through the 1890s, mail-order shopping surged, and the new century saw

massive multistory department stores covering millions of acres of selling space. Retailing was already passing decisively from small shopkeepers to corporate giants who had access to

investment bankers and drew on assembly-line production of commodities, powered by fossil fuels; the traditional objective of making products for their self-evident usefulness was displaced

by the goal of profit and the need for a machinery of enticement. “The cardinal features of this culture were acquisition and consumption as the means of achieving happiness; the cult of the

new; the democratization of desire; and money value as the predominant measure of all value in society,” Leach writes in his 1993 book “Land of Desire: Merchants, Power, and the Rise of a

New American Culture.” Significantly, it was individual desire that was democratized, rather than wealth or political and economic power. THE 1920S: “THE NEW ECONOMIC GOSPEL OF CONSUMPTION”

Release from the perils of famine and premature starvation was in place for most people in the industrialized world soon after the Great War ended. U.S. production was more than 12 times

greater in 1920 than in 1860, while the population over the same period had increased by only a factor of three, suggesting just how much additional wealth was theoretically available. The

labor struggles of the 19th century had, without jeopardizing the burgeoning productivity, gradually eroded the seven-day week of 14- and 16-hour days that was worked at the beginning of the

Industrial Revolution in England. In the United States in particular, economic growth had succeeded in providing basic security to the great majority of an entire population. In these

circumstances, there was a social choice to be made. A steady-state economy capable of meeting the basic needs of all, foreshadowed by philosopher and political economist John Stuart Mill as

the _stationary state_, seemed well within reach and, in Mill’s words, likely to be an improvement on “the trampling, crushing, elbowing and treading on each other’s heels … the

disagreeable symptoms of one of the phases of industrial progress.” It would be feasible to reduce hours of work further and release workers for the spiritual and pleasurable activities of

free time with families and communities, and creative or educational pursuits. But business did not support such a trajectory, and it was not until the Great Depression that hours were

reduced, in response to overwhelming levels of unemployment. In 1930 the U.S. cereal manufacturer Kellogg adopted a six-hour shift to help accommodate unemployed workers, and other forms of

work-sharing became more widespread. Although the shorter workweek appealed to Kellogg’s workers, the company, after reverting to longer hours during World War II, was reluctant to renew the

six-hour shift in 1945. Workers voted for it by three-to-one in both 1945 and 1946, suggesting that, at the time, they still found life in their communities more attractive than consumer

goods. This was particularly true of women. Kellogg, however, gradually overcame the resistance of its workers and whittled away at the short shifts until the last of them were abolished in

1985. Even if a shorter working day became an acceptable strategy during the Great Depression, the economic system’s orientation toward profit and its bias toward growth made such a

trajectory unpalatable to most captains of industry and the economists who theorized their successes. If profit and growth were lagging, the system needed new impetus. The short depression

of 1921–1922 led businessmen and economists in the United States to fear that the immense productive powers created over the previous century had grown sufficiently to meet the basic needs

of the entire population and had probably triggered a permanent crisis of overproduction; prospects for further economic expansion were thought to look bleak. The historian Benjamin

Hunnicutt, who examined the mainstream press of the 1920s, along with the publications of corporations, business organizations, and government inquiries, found extensive evidence that such

fears were widespread in business circles during the 1920s. Victor Cutter, president of the United Fruit Company, exemplified the concern when he wrote in 1927 that the greatest economic

problem of the day was the lack of “consuming power” in relation to the prodigious powers of production. Notwithstanding the panic and pessimism, a consumer solution was simultaneously

emerging. As the popular historian of the time Frederick Allen wrote, “Business had learned as never before the importance of the ultimate consumer. Unless he could be persuaded to buy and

buy lavishly, the whole stream of six-cylinder cars, super heterodynes, cigarettes, rouge compacts and electric ice boxes would be dammed up at its outlets.” In his classic 1928 book

“Propaganda,” Edward Bernays, one of the pioneers of the public relations industry, put it this way: > Mass production is profitable only if its rhythm can be > maintained—that is if

it can continue to sell its product in > steady or increasing quantity.… Today supply must actively seek to > create its corresponding demand … [and] cannot afford to wait > until

the public asks for its product; it must maintain constant > touch, through advertising and propaganda … to assure itself the > continuous demand which alone will make its costly plant

profitable. Edward Cowdrick, an economist who advised corporations on their management and industrial relations policies, called it “the new economic gospel of consumption,” in which

workers (people for whom durable possessions had rarely been a possibility) could be educated in the new “skills of consumption.” It was an idea also put forward by the new “consumption

economists” such as Hazel Kyrk and Theresa McMahon, and eagerly embraced by many business leaders. New needs would be created, with advertising brought into play to “augment and accelerate”

the process. People would be encouraged to give up thrift and husbandry, to value goods over free time. Kyrk argued for ever-increasing aspirations: “a high standard of living must be

dynamic, a progressive standard,” where envy of those just above oneself in the social order incited consumption and fueled economic growth. President Herbert Hoover’s 1929 Committee on

Recent Economic Changes welcomed the demonstration “on a grand scale [of] the expansibility of human wants and desires,” hailed an “almost insatiable appetite for goods and services,” and

envisaged “a boundless field before us … new wants that make way endlessly for newer wants, as fast as they are satisfied.” In this paradigm, people are encouraged to board an escalator of

desires (a stairway to heaven, perhaps) and progressively ascend to what were once the luxuries of the affluent. Charles Kettering, general director of General Motors Research Laboratories,

equated such perpetual change with progress. In a 1929 article called “Keep the Consumer Dissatisfied,” he stated that “there is no place anyone can sit and rest in an industrial situation.

It is a question of change, change all the time — and it is always going to be that way because the world only goes along one road, the road of progress.” These views parallel political

economist Joseph Schumpeter’s later characterization of capitalism as “creative destruction”: > Capitalism, then, is by nature a form or method of economic change > and not only never

is, but _never can be stationary_.… The > fundamental impulse that sets and keeps the capitalist engine in > motion comes from the new consumers, goods, the new methods of >

production or transportation, the new markets, the new forms of > industrial organization that capitalist enterprise creates. The prospect of ever-extendable consumer desire,

characterized as “progress,” promised a new way forward for modern manufacture, a means to perpetuate economic growth. Progress was about the endless replacement of old needs with new, old

products with new. Notions of meeting everyone’s needs with an adequate level of production did not feature. The nonsettler European colonies were not regarded as viable venues for these new

markets, since centuries of exploitation and impoverishment meant that few people there were able to pay. In the 1920s, the target consumer market to be nourished lay at home in the

industrialized world. There, especially in the United States, consumption continued to expand through the 1920s, though truncated by the Great Depression of 1929. Electrification was crucial

for the consumption of the new types of durable items, and the fraction of U.S. households with electricity connected nearly doubled between 1921 and 1929, from 35 percent to 68 percent; a

rapid proliferation of radios, vacuum cleaners, and refrigerators followed. Motor car registration rose from eight million in 1920 to more than 28 million by 1929. The introduction of time

payment arrangements facilitated the extension of such buying further and further down the economic ladder. In Australia, too, the trend could be observed; there, however, the base was tiny,

and even though car ownership multiplied nearly fivefold in the eight years to 1929, few working-class households possessed cars or large appliances before 1945. This first wave of

consumerism was short-lived. Predicated on debt, it took place in an economy mired in speculation and risky borrowing. U.S. consumer credit rose to $7 billion in the 1920s, with banks

engaged in reckless lending of all kinds. Indeed, though a lot less in gross terms than the burden of debt in the United States in late 2008, which Sydney economist Steve Keen has described

as “the biggest load of unsuccessful gambling in history,” the debt of the 1920s was very large, over 200 percent of the GDP of the time. In both eras, borrowed money bought unprecedented

quantities of material goods on time payment and (these days) credit cards. The 1920s bonanza collapsed suddenly and catastrophically. In 2008, a similar unraveling began; its implications

still remain unknown. In the case of the Great Depression of the 1930s, a war economy followed, so it was almost 20 years before mass consumption resumed any role in economic life — or in

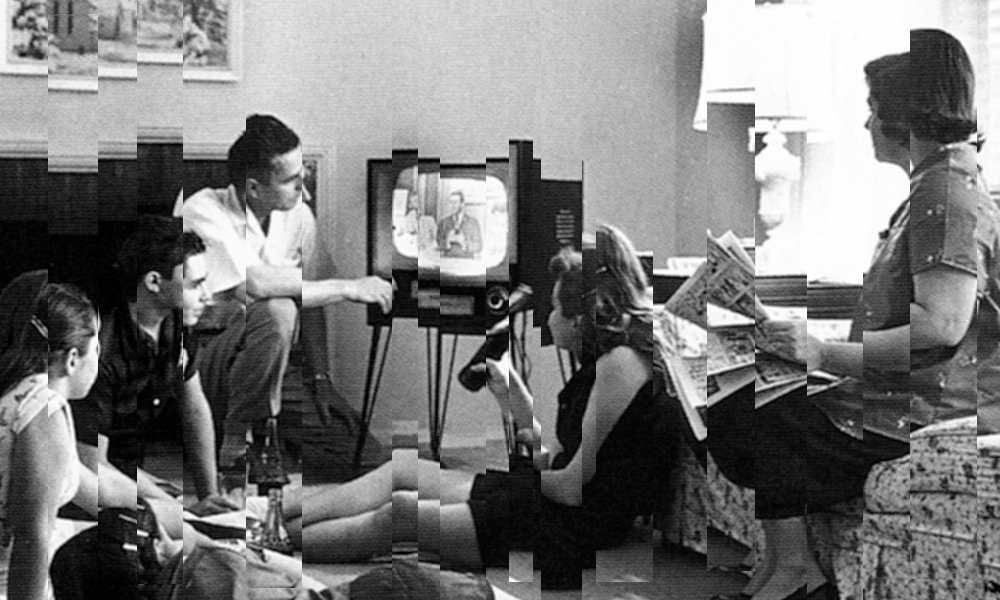

the way the economy was conceived. ------------------------- THE SECOND WAVE Once World War II was over, consumer culture took off again throughout the developed world, partly fueled by the

deprivation of the Great Depression and the rationing of the wartime years and incited with renewed zeal by corporate advertisers using debt facilities and the new medium of television.

Stuart Ewen, in his history of the public relations industry, saw the birth of commercial radio in 1921 as a vital tool in the great wave of debt-financed consumption in the 1920s — “a

privately owned utility, pumping information and entertainment into people’s homes.” “Requiring no significant degree of literacy on the part of its audience,” Ewen writes, “radio gave

interested corporations … unprecedented access to the inner sanctums of the public mind.” The advent of television greatly magnified the potential impact of advertisers’ messages, exploiting

image and symbol far more adeptly than print and radio had been able to do. The stage was set for the democratization of luxury on a scale hitherto unimagined. Though the television sets

that carried the advertising into people’s homes after World War II were new, and were far more powerful vehicles of persuasion than radio had been, the theory and methods were the same —

perfected in the 1920s by PR experts like Bernays. Vance Packard echoes both Bernays and the consumption economists of the 1920s in his description of the role of the advertising men of the

1950s: > They want to put some sizzle into their messages by stirring up our > status consciousness.… Many of the products they are trying to > sell have, in the past, been confined

to a “quality market.” The > products have been the luxuries of the upper classes. The game is to > _make them the necessities of all classes_. This is done by dangling > the

products before non-upper-class people as status symbols of a > higher class. By striving to buy the product—say, wall-to-wall > carpeting on instalment—the consumer is made to feel he

is > upgrading himself socially. Though it is status that is being sold, it is endless material objects that are being consumed. In a little-known 1958 essay reflecting on the

conservation implications of the conspicuously wasteful U.S. consumer binge after World War II, John Kenneth Galbraith pointed to the possibility that this “gargantuan and growing appetite”

might need to be curtailed. “What of the appetite itself?,” he asks. “Surely this is the ultimate source of the problem. If it continues its geometric course, will it not one day have to be

restrained? Yet in the literature of the resource problem this is the forbidden question.” Galbraith quotes the President’s Materials Policy Commission setting out its premise that economic

growth is sacrosanct. “First we share the belief of the American people in the principle of Growth,” the report maintains, specifically endorsing “ever more luxurious standards of

consumption.” To Galbraith, who had just published “The Affluent Society,” the wastefulness he observed seemed foolhardy, but he was pessimistic about curtailment; he identified the

beginnings of “a massive conservative reaction to the idea of enlarged social guidance and control of economic activity,” a backlash against the state taking responsibility for social

direction. At the same time he was well aware of the role of advertising: “Goods are plentiful. Demand for them must be elaborately contrived,” he wrote. “Those who create wants rank amongst

our most talented and highly paid citizens. Want creation — advertising — is a ten billion dollar industry.” Or, as retail analyst Victor Lebow remarked in 1955: > Our enormously

productive economy demands that we make consumption > our way of life, that we convert the buying and use of goods into > rituals, that we seek our spiritual satisfaction, our ego >

satisfaction, in consumption.… We need things consumed, burned up, > replaced and discarded at an ever-accelerating rate. Thus, just as immense effort was being devoted to persuading

people to buy things they did not actually need, manufacturers also began the intentional design of inferior items, which came to be known as “planned obsolescence.” In his second major

critique of the culture of consumption, “The Waste Makers,” Packard identified both functional obsolescence, in which the product wears out quickly and psychological obsolescence, in which

products are “designed to become obsolete in the mind of the consumer, even sooner than the components used to make them will fail.” Galbraith was alert to the way that rapidly expanding

consumption patterns were multiplied by a rapidly expanding population. But postwar industrial enterprise stoked the expansion nonetheless. The rise of consumer debt, interrupted in 1929,

also resumed. In Australia, the 1939 debt of AU$39 million doubled in the first two years after the war and, by 1960, had grown by a factor of 25, to more than AU$1 billion dollars. This new

burst in debt-financed consumerism was, again, incited intentionally. TAPPING INTO THE UNCONSCIOUS: IMAGE AND MESSAGE In researching his excellent history of the rise of PR, Ewen

interviewed Bernays himself in 1990, not long before he turned 99. Ewen found Bernays, a key pioneer of the new PR profession, to be just as candid about his underlying motivations as he had

been in 1928 when he wrote “Propaganda”: > Throughout our conversation, Bernays conveyed his hallucination of > democracy: A highly educated class of opinion-molding tacticians is

> continuously at work … adjusting the mental scenery from which the > public mind, with its limited intellect, derives its opinions.… > Throughout the interview, he described PR as

a response to a > transhistoric concern: the requirement, for those people in power, > to shape the attitudes of the general population. Bernays’s views, like those of several other

analysts of the “crowd” and the “herd instinct,” were a product of the panic created among the elite classes by the early 20th-century transition from the limited franchise of propertied men

to universal suffrage. “On every side of American life, whether political, industrial, social, religious or scientific, the increasing pressure of public judgment has made itself felt,”

Bernays wrote. “The great corporation which is in danger of having its profits taxed away or its sales fall off or its freedom impeded by legislative action must have recourse to the public

to combat successfully these menaces.” The opening page of “Propaganda” discloses his solution: > The conscious and intelligent manipulation of the organized habits > and opinions of

the masses is an important element in democratic > society. Those who manipulate this unseen mechanism of society > constitute an invisible government which is the true ruling power of

> our country.… It is they who pull the wires which control the > public mind, who harness old social forces and contrive new ways to > bind and guide the world. The front-line

thinkers of the emerging advertising and public relations industries turned to the key insights of Sigmund Freud, Bernays’s uncle. As Bernays noted: > Many of man’s thoughts and actions

are compensatory substitutes > for desires which [he] has been obliged to suppress. A thing may be > desired, not for its intrinsic worth or usefulness, but because he > has

unconsciously come to see in it a symbol of something else, the > desire for which he is ashamed to admit to himself … because it is > a symbol of social position, an evidence of his

success. Bernays saw himself as a “propaganda specialist,” a “public relations counsel,” and PR as a more sophisticated craft than advertising as such; it was directed at hidden desires and

subconscious urges of which its targets would be unaware. Bernays and his colleagues were anxious to offer their services to corporations and were instrumental in founding an entire industry

that has since operated along these lines, selling not only corporate commodities but also opinions on a great range of social, political, economic, and environmental issues. Though it has

become fashionable in recent decades to brand scholars and academics as elites who pour scorn on ordinary people, Bernays and the sociologist Gustave Le Bon were long ago arguing, on behalf

of business and political elites, respectively, that the mass of people are incapable of thought. According to Le Bon, “A crowd thinks in images, and the image itself immediately calls up a

series of other images, having no logical connection with the first”; crowds “can only comprehend rough-and-ready associations of ideas,” leading to “the utter powerlessness of reasoning

when it has to fight against sentiment.” Bernays and his PR colleagues believed ordinary people to be incapable of logical thought, let alone mastery of “abstruse economic, political and

ethical data,” and saw the need to “control and regiment the masses according to our will without their knowing about it”; PR could thus ensure the maintenance of order and corporate control

in society. The commodification of reality and the manufacture of demand have had serious implications for the construction of human beings in the late 20th century, where, to quote

philosopher Herbert Marcuse, “people recognize themselves in their commodities.” Marcuse’s critique of needs, made more than 50 years ago, was not directed at the issues of scarce resources

or ecological waste, although he was aware even at that time that Marx was insufficiently critical of the continuum of progress and that there needed to be “a restoration of nature after the

horrors of capitalist industrialisation have been done away with.” Marcuse directed his critique at the way people, in the act of satisfying our aspirations, reproduce dependence on the

very exploitive apparatus that perpetuates our servitude. Hours of work in the United States have been growing since 1950, along with a doubling of consumption per capita between 1950 and

1990. Marcuse suggested that this “voluntary servitude (voluntary inasmuch as it is introjected into the individual) … can be broken only through a political practice which reaches the roots

of containment and contentment in the infrastructure of man [_sic_], a political practice of methodical disengagement from and refusal of the Establishment, aiming at a radical

transvaluation of values.” The difficult challenge posed by such a transvaluation is reflected in current attitudes. The Australian comedian Wendy Harmer in her 2008 ABC TV series called

“Stuff” expressed irritation at suggestions that consumption is simply generated out of greed or lack of awareness: > I am very proud to have made a documentary about consumption that

> does not contain the usual footage of factory smokestacks, landfill > tips and bulging supermarket trolleys. Instead, it features many > happy human faces and all their wonderful

stuff! It’s a study of a > love affair as much as anything else. In the same vein, during the Q&A after a talk given by the Australian economist Clive Hamilton at the 2006 Byron Bay

Writers’ Festival, one woman spoke up about her partner’s priorities: Rather than entertain questions about any impact his possessions might be having on the environment, she said, he was

determined to “go down with his gadgets.” The capitalist system, dependent on a logic of never-ending growth from its earliest inception, confronted the plenty it created in its home states,

especially the United States, as a threat to its very existence. It would not do if people were content because they felt they had enough. However over the course of the 20th century,

capitalism preserved its momentum by molding the ordinary person into a consumer with an unquenchable thirst for its “wonderful stuff.” ------------------------- _KERRYN HIGGS is an

Australian writer and historian. She is the author of “Collision Course: Endless Growth on a Finite Planet,” from which this article is adapted._