Play all audios:

ABSTRACT Nanomaterials in the blood must mitigate the immune response to have a prolonged vascular residency in vivo. The composition of the protein corona that forms at the

nano-biointerface may be directing this, however, the possible correlation of corona composition with blood residency is currently unknown. Here‚ we report a panel of new soft single

molecule polymer nanomaterials (SMPNs) with varying circulation times in mice (t1/2β ~ 22 to 65 h) and use proteomics to probe protein corona at the nano-biointerface to elucidate the

mechanism of blood residency of nanomaterials. The composition of the protein opsonins on SMPNs is qualitatively and quantitatively dynamic with time in circulation. SMPNs that circulate

longer are able to clear some of the initial surface-bound common opsonins, including immunoglobulins, complement, and coagulation proteins. This continuous remodelling of protein opsonins

may be an important decisive step in directing elimination or residence of soft nanomaterials in vivo. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS DEVELOPMENT OF IONIC LIQUID-COATED PLGA

NANOPARTICLES FOR APPLICATIONS IN INTRAVENOUS DRUG DELIVERY Article 19 July 2023 POLYMERIC PARTICLE-BASED THERAPIES FOR ACUTE INFLAMMATORY DISEASES Article 19 July 2022 ENHANCING IN VIVO

CELL AND TISSUE TARGETING BY MODULATION OF POLYMER NANOPARTICLES AND MACROPHAGE DECOYS Article Open access 18 May 2024 INTRODUCTION Nanomaterials are cleared from the blood by the

mononuclear phagocyte system1,2. The interaction of nanomaterials with circulating blood components is crucial in governing their biological fate and functions and is highly relevant to

biocompatibility and toxicity2. Studies using a variety of nanomaterials‚ including liposomes, micelles, inorganic/organic hard nanoparticles, polymers‚ and ‘self’ peptide conjugated

nanoparticles have been performed to predict how physiochemical characteristics influence the blood residency or immune recognition of nanomaterials2,3,4,5. However, there is a still lack of

fundamental understanding on how some nanomaterials are eliminated rapidly from the blood and accumulate in organs, while others achieve long residency in blood6. A detailed understanding

of this fundamental phenomenon is highly useful in generating long acting therapeutics and farther our understanding on the biocompatibility/toxicity of nanomaterials. Rapid deposition of

protein opsonins on nanomaterial’s surface upon introduction into the blood is well established and believed that they control the immune recognition of nanomaterials7,8,9,10,11,12,13. Some

key insights into the differences in protein composition at the interface with time, size, and surface chemistry of nanomaterials have been reported in vitro to understand the immune evasion

of nanomaterials, however sparse information is available on this nano-biointerface inside the body11,14,15,16. Moreover, it is vital to investigate the unanswered questions including

whether the nano-biointerface is dynamic in vivo or the initially adsorbed protein opsonins are the de facto characteristics of a system that guides its fate in circulation. Importantly,

biological systems are highly responsive to external stimuli, such as the introduction of nanomaterials, which could continuously alter the material–protein interactions and may be

functionally relevant to protein opsonin changes. Thus, a thorough investigation of the evolution of proteins at the nano-biointerface in vivo over extended time periods could provide clues

into this unresolved puzzle. Many of the currently used systems, both in vitro and in vivo, do not qualify as long circulating nanomaterials to assess their in vivo protein corona due to

their poor chemical and biological stability11,15,17. Highly biocompatible and biologically stable nanomaterials‚ can be easily separated from blood‚ are very much desirable to perform such

studies, which have not been previously explored. In this work, we developed a class of highly hydrophilic, biocompatible, soft single molecule polymer nanomaterials (SMPNs) with different

blood circulation profiles (short to ultra-long) while maintaining similar surface chemistry to uncover the interplay between the nature of nano-biointerface and blood residency in vivo over

clinically relevant time scales. We performed unbiased tandem mass spectrometry-based proteomics to reveal the evolution of protein composition with time on SMPNs in vivo and their fate in

circulation. RESULTS BLOOD CIRCULATION OF SMPNS A multitude of nanomaterial characteristics including surface chemistry, hydrophilicity, size and shape, charge, rigidity, stability, and

biocompatibility are detrimental to achieve long blood circulation or its susceptibility to accumulate in organs18,19,20. In particular, soft and non-fouling materials showed the promise of

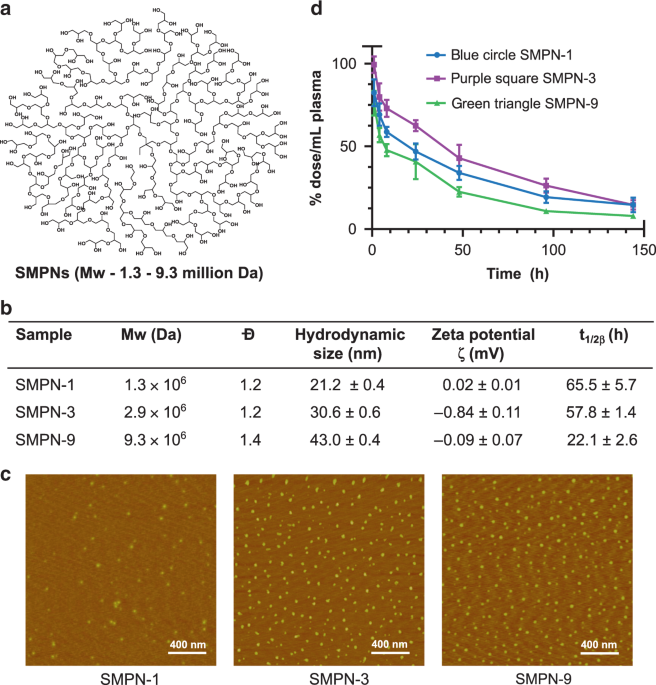

avoiding opsonization. We developed three mega hyperbranched polyglycerol based SMPNs by the polymerization of glycidol (Supplementary Table 1)—SMPN-1, SMPN-3, and SMPN-9—named after their

molecular weight (_M__w_), 1.3, 2.9, and 9.3 million Daltons, respectively (Fig. 1a, b, Supplementary Fig. 1)21. The SMPNs are very compact, hydrophilic, stable, and biocompatible. They have

neutral surface charge and possess a high number of functionalizable end groups (Fig. 1a, b and Supplementary Fig. 2). The average hydrodynamic sizes of the SMPN-1, −3, and −9 are 21, 31,

and 43 nm, respectively (Fig. 1b). Their spherical shape and nearly monodisperse nature are identified by atomic force microscopy analysis (Fig. 1c) and gel permeation chromatography

(Supplementary Fig. 1). This further supported the formation of single chain polymer nanomaterials without any additional modification, formulation, or chain collapse. To investigate the in

vivo fate of nanomaterials, we initially studied the pharmacokinetic behaviour of SMPNs. Tritium labelled SMPNs were injected intravenously (i.v.) in mice (Balb/c) (_n_ = 4) and the

concentration of SMPNs in plasma was measured (Fig. 1d). The circulation half-lives (_t_1/2β) and pharmacokinetic parameters of SMPNs were obtained by fitting the data using a

two-compartment open model (Fig. 1b, 1d and Supplementary Table 2)22. Given that SMPNs have similar surface chemistry, the data supported that molecular weight of the SMPNs has a dominant

role on vascular residence time. SMPN-1 showed _t_1/2β of 65.5 ± 5.7 h, while SMPN-3 and -9 generated 57.8 ± 1.4 h and 22.1 ± 2.6 h respectively (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Table 2). As per

our knowledge, the circulation half-life of SMPN-1 (_t_1/2β = 65 h) is the highest reported to date for any single molecule nanomaterial systems, including nanogels23, stealth liposomes24,

micellar systems25, nanoparticles26, dendrimers or hyperbranched polymers20,25, and PEGylated systems in healthy mice27. Remarkably, SMPN-1 showed ultra-long circulation without the need of

additional modifications such as the conjugation of hydrophilic polymer chains to reduce the non-specific interactions or ‘self’ peptides. This suggests their inherent ability to minimize

opsonization and evade immune mediated clearance. The pharmacokinetic parameters, such as elimination constants (k2), and area under the curve versus time plot (AUC0→∞), further confirmed

the ultra-long circulation of SMPN-1 compared to the other SMPNs (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Table 2). BIODISTRIBUTION AND CLEARANCE OF SMPNS After demonstrating the long circulation of

selected SMPNs, we examined their biodistribution over a 7-day period. Accumulation of SMPNs in organs was determined by measuring the residual radioactivity of digested organs (Fig. 2a).

The accumulation remains low (1.89–11.85% injected dose/g of organ) in various organs; the distribution of SMPNs showed a good correlation with their _t_1/2. The short circulating SMPN-9

accumulated more in the liver (****_p_ < 0.0001), spleen (*_p_ < 0.05), and kidney (*_p_ < 0.05) compared to the ultra-long circulating SMPNs after 144 h, however, no significant

differences were observed in lungs. Irrespective of their _t_1/2, the accumulation of SMPNs in the kidney and lung was decreased from 1 to 144 h and this trend was opposite to that of spleen

(Fig. 2a). These highly functionalizable (containing ~14, 500–89,000 hydroxyl groups/per molecule) ultra-long circulating SMPNs with minimal organ accumulation is an addition to the field

of nanomaterials and could be a potential alternative to other masking or camouflaging nanomaterials. To further understand the elimination route and tissue localization of SMPNs, we used

confocal imaging of tissue slices from organs collected at various time points after intravenous (i.v.) injection of fluorophore-labeled SMPNs in Balb/c mice (Fig. 2b, c, Supplementary Figs.

3 and 4, and Supplementary Table 3). A set of images collected from tissue sections of different parts of the organ (_n_ = 40) was used for the distribution analysis of SMPNs. The

distribution of SMPNs in the organs showed marked differences with respect to their _t__1/2_. The quantitative estimation based on the fluorescence method showed some differences with the

biodistribution data obtained from the radio-labelling method (Fig. 2a–c); this is possibly due to the localized accumulation of SMPNs in the organs which is reflected in the fluorescence

quantification of tissue sections unlike complete tissue digestion in the latter case. In the liver, the ultra-long circulating SMPN-1 was distributed homogeneously throughout the organ with

increased accumulation over time (*_p_ = 0.022, 8 vs. 48 h), while the short circulating SMPN-9 was selectively localized, however, increased accumulation was observed over the time (*_p_ =

0.0078, 8 vs. 48 h) (Fig. 2b, c and Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4). In kidney, SMPN-9 accumulated in both cortical (***_p_ = 0.00016 vs control) and medullary (**_p_ = 0.0029 vs control)

regions within 8 h which was decreased over 48 h. In kidney, SMPN-1 is, in fact, accumulating higher than saline controls at all time points (cortex: **_p_ = 0.0065 (8 h), *_p_ = 0.0146 (48

h); medulla **_p_ = 0.0033 (8 h), *_p_ = 0.0105 (48 h) vs saline control). Although more accumulation was found at 24 h than control, there was no statistical difference found (Fig. 2b, c

and Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4). In the spleen, increased amount of SMPN-1 (*_p_ = 0.037 (8 h), *_p_ = 0.014 (48 h) vs control) are visible in the white pulp, a region of rich in immune

cells (Fig. 2b, c and Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4) with time. Contrastingly, significant SMPN-9 accumulation in the white pulp region was observed only at 8 h (*_p_ = 0.165) and decreased

thereafter. The marked differences in organ accumulation of these SMPNs further suggest their distinct interactions within biological systems. SMPNs were detectable in peripheral blood

leukocytes up to 48 h after injection, however, there was no dependence on their uptake with respect to time and _t_1/2 (Fig. 2d, e, and Supplementary Fig. 5c). This may suggest minimal

involvement of circulating macrophages in the differential elimination of SMPNs from blood circulation. PROTEIN CORONA ON SMPN-1 IN MICE WITH TIME We hypothesized that the striking

difference in circulation profiles for SMPNs in vivo might be originating due to the differences in the protein opsonins at the nano-biointerface of SMPNs. To investigate this, we first

evaluated the composition of in vivo protein corona on SMPN- 1 over different time scales using unbiased label-free quantitative mass spectrometry. The SMPN-1 was isolated from mice (_n_ =

4, included both female and male mice, each biological replicate has three technical replicates) at different time points after i.v. injection. The protocol for isolation of SMPNs was

initially validated with human plasma experiments (Supplementary Fig. 5a). The protein content on SMPNs was significantly different from pure human plasma that subjected to the same

centrifugation/isolation protocol (Supplementary Fig. 5b). We employed the same sequential centrifugation protocol for isolation of SMPNs from mouse plasma collected from in vivo

experiments. The isolation of SMPNs was further validated by fluorescence measurements after collecting fluorophore (HiLyteTM Fluor 647 amine dye) conjugated SMPNs from mice at 8 h

(Supplementary Table 4 and Supplementary Fig. 6). Finally, the samples were digested in situ, and proteomics analysis was performed. Protein identification of protein corona on SMPNs were

manually assigned through searching the mouse taxon of UnitprotKB database. Percent of abundance for each protein was calculated using label-free quantification (LFQ) intensities relative to

the total sum of protein LFQ intensities for each group. Technical replicate profiles from each biological sample were averaged. We took snapshots of protein composition on SMPN-1 at 8, 24,

and 48 h, with as limited as 0.001% relative total protein content detected on its bio-interface. Within the group, correlation analysis of the biological replicates performed in Perseus

software demonstrated good replicate correlation as depicted in the binary scatterplots and LFQ intensity histograms (Supplementary Figs. 7–10). The list of top 25 most abundant proteins and

the complete list of proteins on SMPN-1 from four biological replicates (three technical replicates for each biological sample) were shown (Supplementary Table 5 and Supplementary Data 1).

The raw data set is available via ProteomeXchange with identifier PXD018958 [https://doi.org/10.25345/C5NX3V]. Both qualitative and quantitative changes in protein composition at the

nano-biointerface of SMPN-1 were observed with time in circulation. The identified proteins on SMPN-1 were grouped according to their biological functions and were shown as relative

percentages in Fig. 3a. A major portion of the protein opsonins at 8 h was composed of coagulation proteins followed by tissue leakage proteins, acute phase reactants, lipoproteins,

complement, and immunoglobulins (Fig. 3a). Each time point showed changes in protein abundance and composition (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Tables 6 and 7). Over the time, the coagulation and

complement proteins were decreased and immunoglobulin proteins, acute phase reactants, and lipoproteins were increased in abundance (Fig. 3c–g). Apparently, protein corona at 24 h was quite

distinct from the rest of the time points across all the functional protein groups (Fig. 3c–g). A pictorial representation of changes in major group of proteins on SMPN-1 with time in

circulation is detailed in Figures 3c to 3h. This analysis highlights a few important points, including the highly dynamic nature of nano-biointerface in vivo and the evidence of a

continuous remodeling process at the nano-biointerface both qualitatively and quantitatively. This incessant process might be aiding the generation of long blood residency of SMPN-1.

COMPARISON OF PROTEIN CORONA ON DIFFERENT SMPNS WITH TIME We next investigated the composition of protein opsonins on three SMPNs to decode if there is a correlation between blood residency

and the functional role of proteins at the nano-biointerface. Protein corona snapshots of SMPNs were obtained after their isolation from mice. The list of complete set of proteins and top 25

most abundant proteins identified on SMPNs at 8 and 48 h (Supplementary Data 1 and Supplementary Tables 8 and 9). Fig. 4 summarizes the protein corona of all SMPNs (8 and 48 h) based on

biological function and the analysis of common as well as unique proteins with respective to nanoparticle and time (Supplementary Tables 10 and 11 and Supplementary Data 1). We observed

quantitative changes in the top-25 proteins (Supplementary Fig. 11). As shown in Fig. 4a, distinguishable changes in protein composition were observed on SMPNs with different _t_1/2 even

though their surface chemistry is similar. The evolution of protein corona on ultra-long circulating and short circulating SMPNs is remarkably different if we look into the details of

protein fingerprints at the nano-biointerface in terms of biological function as well as the molecular weight of the proteins (Figs. 4a and 4b). The relative percentage of proteins of common

opsonins, including complement proteins, and coagulation proteins were decreased on SMPN-1 from 8 to 48 h. Over the time, the adsorption of high molecular weight proteins (>200 kDa) was

increased on SMPN-3 and decreased for SMPN-1 and 9. Unlike SMPN-9, proteins having molecular weights in the range 150–200 kDa were increased on SMPN-1 and 3 with time. The proteins with

80–100 kDa showed a reverse trend with increased protein content on SMPN-9 over the time. No change was observed for proteins in the molecular weight range 50–60 kDa on SMPN-9 whereas it was

decreased for SMPN-1 and 3 (Fig. 4b). Unique proteins were identified on different SMPNs with time in circulation (Figs. 4c–4d and Supplementary Table 11). Protein snapshots at 8 h showed

that there were 107 proteins common to all SMPNs, however, 52, 8, and 2, distinct proteins were identified on SMPN-1, −3, and −9 respectively (Fig. 4c and Supplementary Tables 10–11). There

were more similarities between SMPN-1 and −3 than SMPN-1 and −9. SMPN-9 showed markedly different composition with only 2 and 4 common proteins between SMPN-3 and SMPN-1, respectively (Fig.

4c). A similar trend was seen at 48 h (Fig. 4d). However, the unique proteins on SMPN-1 and 3 were significantly decreased but the unique proteins moderately increased on SMPN-9. The common

proteins between all the SMPNs were increased from 107 to 185, and the common proteins between SMPN-1 and 3 were decreased from 126 to 67 (Fig. 4d). These variations in unique as well as

common proteins identified on different SMPNs in circulation further reinforce the fact that the protein composition at the nano-biointerface is highly dynamic in vivo and remodeling is a

continuous process (Figs. 4c and 4d). These differences in protein composition might be contributing to the elimination of SMPN-9 from circulation in comparison to SMPN-1. Importantly, the

observed relative protein composition at the nano-biointerface of SMPNs was not simply an expression of protein abundance in pure plasma (Supplementary Fig. 12). Apparently, these kinetics

are not solely explained by mere quantitative changes as described in the literature8 and even simple Vroman effect could not solely explain the varied compositional fingerprint over the

time as well as with the molecular weight of SMPNs. We believe that soft hydrophilic nature of the interface on SMPNs generates such loosely bound protein corona and thus, facilitating the

remodeling process. To further look into the details of the proteins, we analyzed the protein corona with respect to their biological function, (Fig. 5a–f). In general, coagulation proteins

constitute a major portion of the protein corona at 8 h regardless of their t_1/2_ but the protein content was decreased with time (Fig. 5a). The presence of a large amount of coagulation

proteins at the nano-biointerface strongly suggests that studies using anticoagulated plasma or serum may not be ideal for comparing nanomaterial’s in vitro characteristics with its in vivo

behaviour as in the former case, the coagulation system was inhibited and in the latter case, most of the coagulation proteins were removed. Complement proteins decreased for SMPN-1 and

increased for SMPN-3 and 9 (Fig. 5b). Irrespective of SMPNs, immunoglobulins and acute phase reactants were increased over 48 h (Fig. 5c and 5e). For SMPN-1 and 3, the abundance of

lipoproteins was increased, and it was decreased for SMPN-9 (Fig. 5d). The plasma components showed different behaviour; they increased over the time for SMPN-3 and substantially decreased

for SMPN-9 (Fig. 5f). No visible difference was found for SMPN-1. Taken together, these data demonstrated the dynamic nature of protein opsonins on SMPNs in vivo circulation and the

remodeling of nano-biointerface with respect to its blood residency. Apparently, the collective protein fingerprint at the nano-biointerface is dictating the SMPN’s residence in the blood

compartment or its clearance, rather than the contribution or role of a specific class of adsorbed proteins8,11,16. Based on our current data, we believe that a dynamic protein flux may be

essential for opsonization or immune recognition of soft nanomaterials in healthy mice (Fig. 6). The protein corona dynamics might depend on the unique characteristics of the system, for

instance hard or soft particles, hydrophilic or hydrophobic, and charged or neutral, and it would be also influenced by species and/or phenotype of the host. Interestingly, we observed

initial hints on sex differences on protein corona on SMPNs, however, further investigation is needed to validate this (Supplementary Fig. 13). Importantly‚ the current data may not be

generalized for all types of nanomaterials. Further investigation into this dynamic protein flux at the biointerface are highly recommended to identify the protein flux on different types of

nanomaterials, predict the biological outcome, and investigate the interactions in various diseases conditions. Further studies using this new model are needed to understand if any specific

functional protein groups or proteins could influence the formation of dynamic protein flux. Such studies might offer a unique opportunity to better design novel materials, which evade

immune recognition with minimal toxicity and have long blood residence. In summary, we reported a class of single molecule polymer nanomaterials with varying residency in mice as a relevant

model to improve our understanding on interactions at the nano-biointerface in vivo. Our analysis on protein composition of nanomaterials isolated from mice at different time points (hours

to days) confirmed that the protein composition at the biointerface is highly dynamic and remodelled while in circulation. The remodelling of protein opsonin composition at the

nano-biointerface may be the key for long blood residence time or faster clearance from circulation. SMPNs that release initially bound common opsonins can evade the immune system and can

reside in blood for longer time periods. We believe the soft and hydrophilic nature of the current nanomaterials result in less stable protein interaction at the interface and may be

contributing to the observed protein corona remodelling. The data presented here will have important implications in the field of nanotoxicology of nanomaterials and provide insights into

the designing safe and immune system evading polymeric nanomaterials. METHODS MATERIALS All the reagents and chemicals were purchased from Sigma–Aldrich (Oakville, Ontario) and used without

further purification unless otherwise mentioned. Deuterated solvents (D2O and MeOD, 99.8% D) were purchased from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Inc. HiLyteTM Fluor 647 amine dye was

purchased from Anaspec (Fremont, California). Glycidol was purified by vacuum distillation at 45 °C and stored over flame dried molecular sieves (4 Å) at 4 °C under argon. Tritiated methyl

iodide solution in toluene was purchased from ARC Radiochemical (St. Louis, MO) and used it after dilution in anhydrous dimethylsulfoxide. NMR spectra (1H, 13C, and inverse-gated (IG) 13C)

were recorded on a Bruker Avance 300 and 400 MHz NMR spectrometers. Degree of branching was measured in deuterated water (D2O) with a relaxation delay of 6 s, using an equation, DB = 2D/(2D

+ L), where D and L represent the intensities of the signals corresponding to the dendritic and linear units respectively28. Absolute molecular weights of the polymeric nanomaterials were

determined by gel permeation chromatography (GPC) on a Waters 2695 separation module fitted with a DAWN HELEOS II multiangle laser light scattering (MALS) detector coupled with Optilab T-rEX

refractive index detector, both from Wyatt Technology, Inc., Santa Barbara, CA. GPC analysis was performed using Waters ultra-hydrogel columns (guard, linear and 120) and 0.1 N NaNO3 buffer

(pH = 7.0) was used a mobile phase, and dn/dc value for nanomaterials used is 0.12 mL/g. Zeta potential measurements were performed on zetasizer (Malvern). Fluorescence measurements were

performed on a Varian Cary Eclipse Fluorimeter (Agilent Technologies). SYNTHESIS OF SMPNS All the SMPNs were synthesized according to the following protocol21. The macroinitiator,

hyperbranched polyglycerol (HPG), was synthesized according to the following protocol28. A representative synthetic protocol for SMPN-9 was given here. All the reaction steps were performed

under an inert atmosphere. The macroinitiator, HPG (Mw-840 kDa, Đ-1.2) (2.5 G, 0.034 mols of total OH groups) was dissolved in anhydrous MeOH (5.0 mL) and made a thin film around the walls

of flame dried three neck round bottom flask and dried the polymer under vacuum at 75 °C for 24 h to completely remove any minute amounts of water and methanol. Anhydrous DMF (35 mL) was

added to the dried polymer and make sure that it was completely soluble. To this solution, KH suspension in oil (30 %) (targeted 10% hydroxyl groups for deprotection, 80 mg, 1 eq) was added

slowly. Reaction temperature was raised to 95 °C, stirred for 30 min to ensure all the macroinitiator was completely dissolved. To this homogenous solution, dried glycidol (51 mL) was added

slowly (1.4 mL/h) after connecting the flask to an overhead stirrer (stirring speed-200 rpm). After glycidol addition was completed, stirring of the reaction mixture was continued for

another 6 h, then cooled to RT and quenched slowly with 0.01 M HCl. The polymer was dissolved in methanol and precipitated in acetone (precipitated two more times). The precipitate was

further dissolved in water and purified by dialysis (RC dialysis membrane MWCO-50,000 Da) against water for 5 days (water replacements for every 8 h). The SMPN-9 was stored as an aqueous

solution at 4 °C (yield-74%). The SMPN-9 was characterized by NMR and GPC-MALS. A similar protocol was used for the synthesis of SMPN-3 and SMPN-1 except that the amount of glycidol used

(see the details for the amount of glycidol used in different experiments, Supplementary Table 1). CONJUGATION OF FLUOROPHORE TO SMPNS 1,2-Diol groups (<1%) of the SMPNs were converted

into aldehydes by treating SMPNs with NaIO4 (1 eq) in water using our published protocol29. The reaction mixture was stirred at RT for overnight and dialyzed against water for 24 h using

dialysis membrane (MWCO-50, 000 Da, water replacements for every 6 h). SMPNs were labeled with HiLyteTM Fluor 647 Amine dye (Anaspec) via reductive amination and the resultant product was

reduced with NaCNBH3 (3 eq). Finally, the remaining free aldehydes were quenched using ethanolamine (20 eq) and dialyzed against water using a cellulose dialysis membrane for 48 h (water

replacements for every 8 h, RC dialysis membrane MWCO-50,000 Da). SMPN-dye conjugates were characterized by fluorescence spectroscopy to make sure that all the conjugates have loaded with a

similar quantity of dye (Supplementary Table 3). DETERMINATION OF HYDRODYNAMIC SIZE AND CHARGE OF SMPNS The hydrodynamic size of the SMPNs were measured in 0.1 M NaNO3 buffer using multi

angle laser light scattering (MALS) detector (DAWN HELEOS II) coupled with Quasi-Elastic Light Scattering (QELS) detector from Wyatt Technology, Inc., Santa Barbara, CA). Zeta potential of

SMPNs was obtained using Malvern Zetasizer (Nano ZS90, He-Ne laser 633 nm) and using disposable folded capillary cells. For zeta potential measurements, three sets of measurements consisting

of 100 runs each were conducted in 150 mM NaCl solution at 25 °C. Count rates were 187.4, 145.3, and 39.5 kcps, respectively, for SMPN-1, -3, and -9. DETERMINATION OF MORPHOLOGY OF SMPNS

The morphology of SMPNs was determined using atomic force microscopy (AFM). SMPNs were dissolved in water at a concentration between 0.05 and 0.1 mg/mL. Ten microliters of the solution was

dropped onto a cleaned Si wafer and dried overnight. The morphology of the deposited SMPNs was acquired in tapping mode in air with using a silicon probe (spring constant of 42 N/m and

frequency of 320 kHz) and AFM with multimode Nanoscope IIIa controller (Digital Instruments, Santa Barbara, CA), equipped with an atomic head of 130 × 130 μm2 scan range. RADIOLABELLING OF

SMPNS Radiolabelling of SMPNs (SMPN-1, 3, and 9) was performed according to the following protocol30. Briefly, the dried SMPN-1 (11 mg, Mw- 1.3 × 106, 100 nmol) was dissolved in dry DMSO (5

mL) under argon and NaH (0.3 mg, 140 μmol) was added. After stirring the solution at room temperature for 2 h, C3[H]3I (100 μL) was added to methylate around 1% of the hydroxyl groups. The

reaction mixture was stirred for another 20 h at room temperature and quenched the reaction mixture by the addition of water (2 mL). Tritiated SMPNs were purified by dialysis against water

(RC dialysis membrane MWCO 1000) until the radioactivity of dialysate reached very minimal (50–100 dpm). The labeled nanomaterial solution was were filtered through 0.2 μm syringe filter,

and concentration (mg/mL) was determined by weighing the dry nanomaterials after freeze drying the known volume (50 μL) of SMPNs. The specific activity of the SMPN was measured by

scintillation counter. The osmolarity of the SMPN was adjusted by adding appropriate amount of NaCl and used it for pharmacokinetic and biodistribution studies. SMPN-3 and SMPN-9 were also

labeled using similar protocols. CIRCULATION HALF-LIFE AND BIODISTRIBUTION OF SMPNS Female Balb/c mice (_n_ = 4, 6–8 weeks) were injected intravenously (bolus) via lateral tail vein with a

solution of tritiated SMPNs at a concentration of 1 mg/mL (four mice per group) at the prescribed dose of 20 mg/kg. Mice were sourced from Envigo. Mice were housed in cages in normal

thermoneutral temperatures (between 24 and 26 °C) under stable 50% humidity conditions using light dark cycles of 12/12. The injected volume was 200 μL per 20 g mouse. Mice were terminated

at different time points (1, 4, 8, 24, 48, 96, and 144 h) by CO2 inhalation, and blood was collected by cardiac puncture. Plasma was isolated by centrifuging the blood samples at 2000 g for

10 min. Aliquots of plasma (50 μL) were analyzed for their radioactivity by scintillation counting. Major organs, including liver, spleen, kidney, heart, and lung were removed from all the

animals after the termination process, weighed, and processed for radioactivity measurements. Livers were made into a 30% homogenate in a known amount of water using a polytron tissue

homogenizer. All other organs were dissolved in 500 μL Solvable®. Aliquots (in triplicates) of 200 μL of the organ solutions were transferred to scintillation vials and the vials were

incubated at 50 °C overnight or up to a few days until completely dissolved, then cooled to room temperature prior to addition of 200 mM EDTA (50 μL), 10 M HCl (25 μL) and 30% H2O2 (200 μL).

This mixture was incubated for 1 h at RT prior to addition of scintillation cocktail (5 mL). Radioactivity of the samples was measured by scintillation counting. The circulation half-lives

(_t_1/2β) and pharmacokinetic parameters of SMPNs were obtained by fitting the data using a two-compartment open model29. ISOLATION OF SMPNS FROM HUMAN PLASMA Huma plasma was isolated from a

healthy donor from whole blood collected in citrate tubes by centrifugation for 2000 g for 15 min. Next, plasma was centrifuged at 10,000 g for 15 min in order to remove debris and

microparticles. The isolation protocol is as described for our in vivo experiments where SMPNs (500 mg/kg, or approximately 6.25 mg/mL) were incubated in human plasma for 1 h at 37 °C. SMPNs

were isolated from plasma fractions by ultracentrifugation (Beckman Coulter Optima Centrifuge, TLA 100.3 rotor) at 202,507 g for 1.5 h31. After initial centrifugation, the supernatant was

removed and the pellet was washed with saline solution (0.5 mL). Centrifugation (1.5 h) and resuspension (0.5 mL, at physiological pH) were repeated five times. Finally, the SMPN samples

were reconstituted in saline (0.2 mL, at physiological pH) and protein content on the samples (5 µL) was measured using Nanodrop™ Spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific ND-2000) on protein

A280 mode (Supplementary Table 5). SMPNS’ ISOLATION FROM MICE AFTER INTRAVENOUS ADMINISTRATION Mice (female and male, Balb/c, _N_ = 4, 6–8 weeks) were administered an intravenous injection

of SMPN-1, 3, or 9 at a dose of 500 mg/kg. Mice were sourced from Envigo. Mice were housed in cages in normal thermoneutral temperatures (between 24 and 26 °C) under stable 50% humidity

conditions using light dark cycles of 12/12. Blood samples were collected at 8, 24, and 48 h for mice injected with SMPN-1 and at 8 and 48 h for mice injected with SMPN-3, and 9. The time

points were selected based on the circulation time and to obtain a higher amount of isolated SMPNs for analysis. After the initial isolation of plasma fractions from the blood samples as

described above and subsequent centrifugation at 10,000 g for 15 min to remove debris, a sequential centrifugation and washing protocol was used to isolate SMPNs. SMPNs were isolated from

plasma fractions by ultracentrifugation at 200,000 g for 1.5 h31. After initial centrifugation, the supernatant was removed and the pellet was washed with saline solution (0.5 mL).

Centrifugation (1.5 h) and resuspension (0.2 mL, at physiological pH) was repeated five times. Finally, the SMPN samples were reconstituted in saline (0.2 mL, at physiological pH) and

protein content on the samples (5 µL) was measured using NanoDrop™ UV-Vis Spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific ND-2000) on protein A280 mode (Supplementary Table 5). Equal amounts of protein

were taken from the suspension for proteomics analysis. Samples were digested for immediately for proteomic analysis. To validate our SMPN isolation protocol, SMPNs were labeled (for

protocol see conjugation of fluorophore to SMPNs) with HiLyteTM Fluor 647 amine dye and injected them in mice. After the isolation (8 h) of the nanoparticles from the plasma, fluorescent

measurements of the conjugated SMPNs were performed to detect the presence of our SMPNs in the isolated suspension. Fluorescence measurements were performed for isolated SMPNs to make sure

that SMPNS are isolated with proteins (Supplementary Fig. 5) and samples were digested for immediately for proteomic analysis. LC-MS ANALYSIS OF TRYPTIC DIGESTS Samples (10 µg) were

incubated with dithiothreitol alkylated (0.25 µg, 30 min, 37 °C) with iodoacetamide (1.25 µg, 30 min, 37 °C), and then digested with trypsin (0.25 µg, 18.5 h in 37 °C) followed by extraction

at a 1:50 protein:enzyme ratio, essentially as described32. Peptides (10 µG) were acidified (one volume 1% TFA), desalted on a high capacity C18 STAGE tip33, and solubilized in 0.1% formic

acid. 2 μg of digested peptides were analyzed on nanoflow-LC-MS/MS system (Bruker Impact II Q-Tof, with Proxeon EasyLC system, featuring in-house packed 400 mm × 50 µm integrated emitter

columns, containing C18 stationary phase ReproSil-Pur 120 C18-AQ 3 μm (Dr Maisch, Ammerbuch-Entringen, Germany) and run with 90 min H2O:ACN gradients. The LC C18 columns included a fritted

trap column with, pulled-tip and a 50-cm analytical column produced and packed in-house. Peptides were separated using a 70 min linear gradient of increasing Buffer B. Buffers A and B were

0.1% formic acid and 0.1% formic acid and 80% acetonitrile, respectively. Data were acquired with the instrument set to scan from 200 to 2000 m/z, 100 μs transient time, 10 μs prepulse

storage, 7 eV collision energy, 1500 Vpp collision RF, _a_ + 2 default charge state (i.e., if charge state could not be assigned, it was assumed to be +2), intensity-dependent MS/MS

acquisition rates ranged from 4 to 16 Hz, 3.0 s cycle time, and the intensity threshold was 250 cts. Raw data was searched against the Uniprot Mouse proteome (uniprot.org) using MaxQuant

(v.1.5.3.30)34. MaxQuant search settings are included: trypsin cleavage specificity, one allowed missed cleavage, fixed carbamidomethyl modification, variable oxidated methionine and

N-terminal acetylation, 0.07 Da precursor mass tolerance, 40 ppm fragment mass tolerance, and 1% protein and peptide FDR calculation based on reverse hits. Label-free quantitation (LFQ) was

enabled (with min ratio count 1) and used for intensity comparisons35. The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE partner

MassIVE repository (UCSD, San Diego, CA, USA) with the data set identifier: PXD018958. The corresponding ProteomeXchange details are available at

http://proteomecentral.proteomexchange.org/cgi/GetDataset?ID=PXD018958. PROTEOMEXCHANGE SUBMISSION DETAILS Project Name: Blood circulation of soft nanomaterials is governed by dynamic

remodeling of protein opsonins at nanobiointerface. Project accession code: PXD018958 Project https://doi.org/10.25345/C5NX3V. PROTEIN IDENTIFICATION AND REPRODUCIBILITY ANALYSIS Protein

identification of protein corona on SMPNs was manually assigned through searching the mouse taxon of UnitprotKB database. Peptide fragment hits pertaining to other species and fragments of

mouse hemoglobin were removed as contaminants from the isolation protocol. Percent abundance for each protein was calculated using label-free quantification (LFQ) intensities relative to the

total sum of protein LFQ intensities for each group. Average profile data from three technical replicates are shown for four different mice (biological replicates) are shown for each group.

Reproducibility analysis (scatterplots and Pearson correlation between biological replicates for each treatment group at each time point) was conducted on Perseus Data Visualization

Software by MaxQuant. Protein hits from false positive and known common contaminants were removed. Data was log(2) transformed. Proteins were considered quantifiable if able to be quantified

at least three times with an LFQ intensity of 20 in at least 1 treatment group. Missing values were imputed into the data table from a normal distribution with an imputation width 0.3 and

downshift 1.8 and plotted on multi-scatter plots and histograms. SMPN ACCUMULATION AND UPTAKE IN ORGANS AND CELLS SMPN accumulation and uptake in organs and cells was further evaluated using

fluorescence-based measurements. Female Balb/c mice (_N_ = 4, 6–8 weeks) were given an intravenous injection of fluorophore-conjugated SMPN-1 and SMPN-9 at a dose of 500 mg/kg. Mice were

sourced from Envigo. Mice were housed in cages in normal thermoneutral temperatures (between 24 and 26 °C) under stable 50% humidity conditions using light dark cycles of 12/12. Blood and

organs (liver, kidney, spleen and lung) were harvested at 8, 24, and 48 h and stored in 10% formalin for 4 °C for up to 1 week prior to processing for histology. 10 µm cryosections of liver,

kidney and spleen were prepared for assessment of SMPN accumulation in organs by confocal microscopy (Zeiss III Spinning Disk Confocal). We have selected representative images and were

included in quantification (in total, _n_ = 40). All the images have been shown at the same magnification with scale bars included. Buffy coat fractions were isolated from the blood samples

and washed 3 times with PBS. A Cytoflex flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter) was used to identify the leukocyte population (10,000 cells per animal analyzed) stained with FITC-labelled mouse

anti-human CD45 antibody (Immunotech; cat. no. IM0782U, 1:40 dilution) and assess uptake of labelled SMPNs in vivo. HUMAN BLOOD SAMPLE COLLECTION Blood was collected from healthy and

consenting donors at the Centre for Blood Research with protocol approval from the University of British Columbia clinical ethics committee. Whole blood was collected in 3.8% sodium citrate

coated tubes (BD VacutainerTM buffered citrate sodium (0.105 M; 9:1 blood/anticoagulant)). Serum was collected in silica spray coated serum tubes (BD VacutainerTM Plus Plastic Serum) and

prepared by leaving tubes undisturbed to allow for clot formation for 30 min at room temperature, followed by centrifugation at 2000 g for 15 min in an Allegra X-22R centrifuge (Beckman

Coulter, Canada). Platelet rich plasma (PRP) was collected by centrifuging citrated whole blood samples at 150 g for 12 min. Platelet poor plasma (PPP) was collected by centrifuging whole

blood samples at 2000 g for 15 min. Red blood cell (RBC) suspensions were prepared by washing packed red cells with PBS for four times and resuspension in PBS to yield a 20% hematocrit cell

suspension. We followed our published protocols to study the blood compatibility of the SMPNs20,36. ASSESSMENT OF HEMOLYSIS Hemolysis was assessed using the Drabkin’s reagent assay for the

determination of hemoglobin release from lysed red cells. SMPN solutions prepared in saline were incubated with whole blood or washed RBC suspension (1:9 v/v SMPN:blood) for 1 h at 37 °C.

Whole blood incubated with water (1:15 v/v blood:water) was used as a positive control. Saline-incubated whole blood or RBC suspension was used as a normal control. Samples were then added

in duplicates to a 96-well plate containing Drabkin’s reagent. Next, samples were centrifuged at 12,000 g for 1 min to collect and add supernatant to wells. Upon mixing with the reagent

hemoglobin is rapidly converted to a cyano derivative, measured spectrophotometrically at 540 nm. Absorbance readings obtained were used to calculate percentage of hemolysis after incubation

with each SMPN sample. Independent studies with three different donors were conducted. ASSESSMENT OF BLOOD COAGULATION Assessment of clotting time via intrinsic coagulation pathway was done

through the activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) test using the Stago coagulation analyzer (ST4 Diagnostica Stago). SMPN samples were incubated with PPP (1:9 v/v polymer:plasma) for

1 h at 37 °C to obtain final SMPN concentrations of 0.1, 1.0 and 10.0 mg/mL. Saline-incubated PPP was used as a normal control. After incubation, innovin® partial thromboplastin reagent

(Dade Behring) was added to the SMPN-PPP mixture and the solution was transferred to cuvette strips. Samples were heated to 37 °C for 2 min before the final addition of calcium chloride

(CaCl2) to initiate clotting. Measurements were done in triplicate and repeated in three different donors. ASSESSMENT OF COMPLEMENT ACTIVATION Activation of the complement system leads to

the eventual formation of the terminal complement complex (TCC, or SC5b-9) that mediates the cell lysis occurring in response to an antigen. Measurement of SC5b-9 was done through enzyme

immunoassay (MicroVue). SMPN samples prepared in saline were incubated with plasma (1:9 v/v) for 1 h at 37 °C. After incubation, SMPN-incubated in platelet poor plasma samples were diluted

using specimen diluent reagent (1:200) and 100 μL was added to each microassay well. Specimen diluent was used as a blank. Plates were incubated with the samples in room temperature for 1 h

and washed three times with prepared wash buffer. After washing, 50 μL of SC5b-9 conjugate was added to each well and incubated at room temperature for 30 min, followed by another set of

washes. After incubation with the conjugate, 100 μL of the substrate was added to each well and incubated at room temperature for 15 min. In all, 100 μL of stop solution was added and the

absorbance measurement at 450 nm was taken within 30 min of halting the reaction. Pre-prepared standards were used to generate a standard curve. Measurements were done in duplicate and

tested in two different donors. ANALYSIS OF TOXICITY OF SMPN-1 IN MICE Histological examination of tissues was performed on liver, kidney, and spleen for a SMPN-1 at 8, 24, and 48 h in

experiments described in the section of SMPN accumulation and uptake in organs and cells. All organs were fixed in 10% formalin fixed organs, parafilm embedded, and sectioned. All the organ

sections were stained for hematoxylin and eosin, and photomicrographs were captured on the Thermo Fisher EVOS XL core imaging system, at a ×20 magnification (0.868 μm/pixel conversion

factor). STATISTICAL ANALYSIS Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 7 (Graphpad Software, San Diego, USA). Group comparisons to control groups were conducted using

_t_-tests. Comparisons between molecular weight groups were performed using one-way ANOVA. If significance was determined, post-hoc multiple comparison analysis was conducted with Tukey

test. Significance was determined with a corrected _α_ value of 0.05. Unless otherwise stated, biocompatibility and uptake data were generated from the mean values of three independent

experiments. All data is presented as mean ± s.d. REPORTING SUMMARY Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article. DATA

AVAILABILITY All generated data in this study is available in the Main Manuscript, Supplementary Information, or Supplementary Data 1. Mass spectrometry proteomic data, including raw data

and search results have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange consortium via the PRIDE partner MassIVE repository (UCSD, San Diego, CA, USA) with the data set identifier: PXD018958. The

corresponding ProteomeXchange details are available at http://proteomecentral.proteomexchange.org/cgi/GetDataset?ID=PXD018958. REFERENCES * Dobrovolskaia, M. A., Aggarwal, P., Hall, J. B.

& McNeil, S. E. Preclinical studies to understand nanoparticle interaction with the immune system and tts potential effects on nanoparticle biodistribution. _Mol. Pharm._ 5, 487–495

(2008). Article CAS Google Scholar * Alexis, F., Pridgen, E., Molnar, L. K. & Farokhzad, O. C. Factors affecting the clearance and biodistribution of polymeric nanoparticles. _Mol.

Pharm._ 5, 505–515 (2008). Article CAS Google Scholar * Duan, X. & Li, Y. Physicochemical characteristics of nanoparticles affect circulation, biodistribution, cellular

internalization, and trafficking. _Small_ 9, 1521–1532 (2013). Article CAS Google Scholar * Walkey, C. D. et al. Protein corona fingerprinting predicts the cellular interaction of gold

and silver nanoparticles. _ACS Nano_ 8, 2439–2455 (2014). Article CAS Google Scholar * Rodriguez, P. L. et al. Minimal ‘self’ peptides that inhibit phagocytic clearance and enhance

delivery of nanoparticles. _Science_ 339, 971–975 (2013). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Wang, B., He, X., Zhang, Z., Zhao, Y. & Feng, W. Metabolism of nanomaterials in vivo: Blood

circulation and organ clearance. _Acc. Chem. Res._ 46, 761–769 (2013). Article CAS Google Scholar * Cedervall, T. et al. Understanding the nanoparticle-protein corona using methods to

quantify exchange rates and affinities of proteins for nanoparticles. _Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA_ 104, 2050–2055 (2007). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Tenzer, S. et al. Rapid

formation of plasma protein corona critically affects nanoparticle pathophysiology. _Nat. Nanotechnol._ 8, 771–781 (2013). Article ADS Google Scholar * Walkey, C. D. & Chan, W. C. W.

Understanding and controlling the interaction of nanomaterials with proteins in a physiological environment. _Chem. Soc. Rev._ 41, 2780–2799 (2012). Article CAS Google Scholar * Weber,

C., Simon, J., Mailänder, V., Morsbach, S. & Landfester, K. Preservation of the soft protein corona in distinct flow allows identification of weakly bound proteins. _Acta Biomater._ 76,

217–224 (2018). Article CAS Google Scholar * Bertrand, N. et al. Mechanistic understanding of in vivo protein corona formation on polymeric nanoparticles and impact on pharmacokinetics.

_Nat. Commun_. 8, 777 (2017). Article ADS Google Scholar * Lundqvist, M. et al. Nanoparticle size and surface properties determine the protein corona with possible implications for

biological impacts. _Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA_ 105, 14265–14270 (2008). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Chen, F. et al. Complement proteins bind to nanoparticle protein corona and

undergo dynamic exchange in vivo. _Nat. Nanotechnol._ 12, 387–393 (2017). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Docter, D. et al. The nanoparticle biomolecule corona: lessons

learned—challenge accepted? _Chem. Soc. Rev._ 44, 6094–6121 (2015). Article CAS Google Scholar * Amici, A. et al. In vivo protein corona patterns of lipid nanoparticles. _RSC Adv._ 7,

1137–1145 (2017). Article CAS Google Scholar * Hadjidemetriou, M. et al. In vivo biomolecule corona around blood-circulating, clinically used and antibody-targeted lipid bilayer nanoscale

vesicles. _ACS Nano_ 9, 8142–8156 (2015). Article CAS Google Scholar * Casals, E., Pfaller, T., Duschl, A., Oostingh, G. J. & Puntes, V. Time evolution of the nanoparticle protein

corona. _ACS Nano_ 4, 3623–3632 (2010). Article CAS Google Scholar * Blanco, E., Shen, H. & Ferrari, M. Principles of nanoparticle design for overcoming biological barriers to drug

delivery. _Nat. Biotechnol._ 33, 941–951 (2015). Article CAS Google Scholar * Moghimi, S. M., Hunter, A. C. & Murray, J. C. Long-circulating and target-specific nanoparticles: theory

to practice. _Pharmacol. Rev_. 53, 283–318 (2001). * Imran ul-haq, M., Lai, B. F. L., Chapanian, R. & Kizhakkedathu, J. N. Influence of architecture of high molecular weight Linear and

branched polyglycerols on their biocompatibility and biodistribution. _Biomaterials_ 33, 9135–9147 (2012). Article CAS Google Scholar * Anilkumar, P. et al. Mega macromolecules as single

molecule lubricants for hard and soft surfaces. _Nat. Commun._ 11, 2139 (2020). Article CAS Google Scholar * Fan, J. & de Lannoy, I. A. M. Pharmacokinetics. _Biochem. Pharmacol._ 87,

93–120 (2014). Article CAS Google Scholar * Zhang, L. et al. Softer zwitterionic nanogels for longer circulation and lower splenic accumulation. _ACS Nano_ 6, 6681–6686 (2012). Article

CAS Google Scholar * Moghimi, S. M. & Szebeni, J. Stealth liposomes and long circulating nanoparticles: Critical issues in pharmacokinetics, opsonization and protein-binding

properties. _Prog. Lipid Res._ 42, 463–478 (2003). Article CAS Google Scholar * Yamamoto, Y., Nagasaki, Y., Kato, Y., Sugiyama, Y. & Kataoka, K. Long-circulating poly(ethylene

glycol)–poly(d,l-lactide) block copolymer micelles with modulated surface charge. _J. Control. Release_ 77, 27–38 (2001). Article CAS Google Scholar * Arami, H., Khandhar, A., Liggitt, D.

& Krishnan, K. M. In vivo delivery, pharmacokinetics, biodistribution and toxicity of iron oxide nanoparticles. _Chem. Soc. Rev._ 8576, 8576–8607 (2015). Article Google Scholar *

Gillies, E. R., Dy, E., Fre, J. M. J. & Szoka, F. C. Biological evaluation of polyester dendrimer: poly(ethylene oxide) ‘bow-tie’ hybrids with tunable molecular weight and architecture.

2, 129–138 (2004). * ul-haq, M. I., Shenoi, R. A., Brooks, D. E. & Kizhakkedathu, J. N. Solvent-assisted anionic ring opening polymerization of glycidol: Toward medium and high molecular

weight hyperbranched polyglycerols. _J. Polym. Sci. Part A Polym. Chem._ 51, 2614–2621 (2013). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Kleifeld, O. et al. Isotopic labeling of terminal amines

in complex samples identifies protein N-termini and protease cleavage products. _Nat. Biotechnol._ 28, 281–288 (2010). Article CAS Google Scholar * Abbina, S. et al. Design of safe

nanotherapeutics for the excretion of excess systemic toxic iron. _ACS Cent. Sci._ 5, 917–926 (2019). CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Yu, K. et al. Modulation of complement

activation and amplification on nanoparticle surfaces by glycopolymer conformation and chemistry. _ACS Nano_ 8, 7687–7703 (2014). Article CAS Google Scholar * Foster, L. J., de Hoog, C.

L. & Mann, M. Unbiased quantitative proteomics of lipid rafts reveals high specificity for signaling factors. _Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA_ 100, 5813–5818 (2003). Article ADS CAS Google

Scholar * Rappsilber, J., Ishihama, Y. & Mann, M. Stop and go extraction tips for matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization, nanoelectrospray, and LC/MS sample pretreatment in

proteomics. _Anal. Chem._ 75, 663–670 (2003). Article CAS Google Scholar * Cox, J. & Mann, M. MaxQuant enables high peptide identification rates, individualized p.p.b.-range mass

accuracies and proteome-wide protein quantification. _Nat. Biotechnol._ 26, 1367–1372 (2008). Article CAS Google Scholar * Cox, J. et al. Accurate proteome-wide label-free quantification

by delayed normalization and maximal peptide ratio extraction, termed MaxLFQ. _Mol. Cell. Proteom._ 13, 2513–2526 (2014). Article CAS Google Scholar * Kainthan, R. K. et al. Blood

compatibility of novel water soluble hyperbranched polyglycerol-based multivalent cationic polymers and their interaction with DNA. _Biomaterials_ 27, 5377–5390 (2006). Article CAS Google

Scholar Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We thank the Macromolecular Hub, CBR, for the use of their research facilities and thank Drs. Marcel Bally and Nancy Dos Santos for help with

animal studies at British Columbia Cancer Research Centre. We acknowledge the funding by Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), Natural Sciences and Engineering Council of Canada

(NSERC) and Canada Foundation for Innovation (CFI). J.N.K. holds a Career Investigator Scholar award from the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research (MSFHR). S.A. acknowledges a MSFHR

postdoctoral fellowship. L.T. acknowledges funding from NSERC CGS-M and the NSERC CREATE NanoMat Program. J.R. was supported by funds from Genome Canada and Genome British Columbia (214PRO).

AUTHOR INFORMATION Author notes * These authors contributed equally: Srinivas Abbina, Lily E. Takeuchi, Parambath Anilkumar. AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Centre for Blood Research, Life

Sciences Institute, The University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, V6T 1Z3, Canada Srinivas Abbina, Lily E. Takeuchi, Parambath Anilkumar, Kai Yu, Iren Constantinescu & Jayachandran

N. Kizhakkedathu * Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, The University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, V6T 2B5, Canada Srinivas Abbina, Lily E. Takeuchi, Parambath Anilkumar,

Kai Yu, Iren Constantinescu & Jayachandran N. Kizhakkedathu * Centre for High Throughput Biology, Michael Smith Laboratories, The University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, V6T 1Z1,

Canada Jason C. Rogalski * Inter University Centre for Biomedical Research & Super Speciality Hospital, Mahatma Gandhi University Campus at Thalappady, Rubber Board P O, Kottayam,

Kerala, 686 009, India Rajesh A. Shenoi * Department of Chemistry, The University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, V6T 1Z1, Canada Jayachandran N. Kizhakkedathu * School of Biomedical

Engineering, The University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, V6T 1Z3, Canada Jayachandran N. Kizhakkedathu Authors * Srinivas Abbina View author publications You can also search for this

author inPubMed Google Scholar * Lily E. Takeuchi View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Parambath Anilkumar View author publications You can

also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Kai Yu View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Jason C. Rogalski View author publications

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Rajesh A. Shenoi View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Iren Constantinescu

View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Jayachandran N. Kizhakkedathu View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed

Google Scholar CONTRIBUTIONS Data was generated by S.A., L.T., A.P., K.Y., R.S., I.C., and J.R. Data analysis was performed by S.A., L.T., K.Y., R.S., I.C., and J.R. Paper was prepared by

S.A., L.T. and J.K. with inputs from other authors. JK provided the grant support and supervision of the project. CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to Jayachandran N. Kizhakkedathu. ETHICS

DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS All authors declare no competing interests. ETHICAL APPROVAL Blood from healthy consented donors was either collected at Centre for Blood Research,

University of British Columbia. The protocol was approved by clinical ethical committee of the University of British Columbia. The animal studies were conducted at the Experimental

Therapeutics Laboratory at the British Columbia Cancer Research Centre, Vancouver, Canada. The protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care Committee (IACC) at the

University of British Columbia. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION PEER REVIEW INFORMATION _Nature Communications_ thanks Morteza Mahmoudi and Stefan Tenzer for their contribution to the peer review of

this work. Peer reviewer reports are available. PUBLISHER’S NOTE Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION PEER REVIEW FILE DESCRIPTION OF ADDITIONAL SUPPLEMENTARY FILES SUPPLEMENTARY DATA 1 REPORTING SUMMARY RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS OPEN ACCESS

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as

long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third

party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the

article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright

holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Abbina, S., Takeuchi, L.E.,

Anilkumar, P. _et al._ Blood circulation of soft nanomaterials is governed by dynamic remodeling of protein opsonins at nano-biointerface. _Nat Commun_ 11, 3048 (2020).

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-16772-x Download citation * Received: 21 May 2019 * Accepted: 26 May 2020 * Published: 16 June 2020 * DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-16772-x SHARE

THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Copy to

clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative